al-Walaja

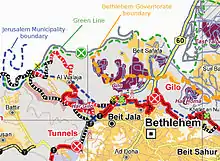

Al-Walaja (Arabic: الولجة) is a Palestinian village in the West Bank, four kilometers northwest of Bethlehem. It is an enclave in the Seam Zone, near the Green Line. Al-Walaja is partly under the jurisdiction of the Bethlehem Governorate and partly of the Jerusalem Municipality. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the village had a population of 2,041 in 2007, mostly Muslims.[6] It has been called 'the most beautiful village in Palestine'.[7]

Al-Walaja | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | الولجة |

| • Latin | Al-Walaja (official) |

| |

Al-Walaja Location of al-Walaja within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°44′27″N 35°8′46″E | |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Bethlehem |

| Founded | 1949 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village council |

| • Head of Municipality | Saleh Hilmi Khalifa |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17,708[1] dunams (17.7 km2 or 6.8 sq mi) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 2,041 |

| Name meaning | "The bosom of the hill"[2] |

al-Walaja

الولجة al-Walaje, el-Welejeh | |

|---|---|

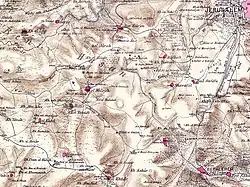

.jpg.webp) 1870s map 1870s map .jpg.webp) 1940s map 1940s map.jpg.webp) modern map modern map .jpg.webp) 1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Al-Walaja (click the buttons) | |

| Palestine grid | 163/127 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Date of depopulation | October 21, 1948[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17,708 dunams (17.7 km2 or 6.8 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,650[1][4] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Amminadav[5] |

Al-Walaja was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, in October 1948.[3] It lost about 70% of its land, west of the Green Line. After the war, the displaced inhabitants resettled on the remaining land in the West Bank. After its occupation by Israel during the Six-Day War, Israel annexed about half of al-Walaja's remaining land, including the neighborhood Ain Jawaizeh, to the Jerusalem Municipality. Large parts of the land were confiscated for the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier and the Israeli settlements of Har Gilo and Gilo, one of the Ring Neighborhoods of Jerusalem.

History

Ottoman period

In 1596, al-Walaja appeared in Ottoman tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Quds of the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 100 Muslim households and 9 bachelors; an estimated 655 persons. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3 % on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, summer crops, vines or fruit trees, and goats or beehives; a total of 7,500 akçe.[8][9]

In 1838, it was noted as a Muslim village, el-Weleje, in the Beni Hasan District west of Jerusalem.[10][11]

An Ottoman village list from about 1870 counted 78 houses and a population of 379, though the population count included men only.[12][13]

In 1883, the PEF's "Survey of Western Palestine" described al-Walaja as a "good-sized" village built of stone.[14]

During the latter half of Ottoman rule, al-Walaja was the administrative seat of the Bani Hasan subdistrict (nahiya), which consisted of over ten villages, including al-Khader, Suba, Beit Jala, Ayn Karim and al-Maliha, and served as the throne village of the al-Absiyeh family.[15]

In 1896 the population of Al-Walaja was estimated to be about 810 persons.[16]

British Mandate

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Walajeh had a population 910, all Muslims,[17] increasing in the 1931 census to 1,206, still all Muslim, in 292 houses.[18] Between 1922 and 1947 the population doubled.[19]

In the 1945 statistics the population of El Walaja was 1,650, all Muslims,[4] and the total land area was 17,708 dunams, according to an official land and population survey. Of this, 17,507 dunams were owned by Arabs, 35 dunams were owned by Jews, and 166 were public property.[1] 2,136 dunams were for plantations and irrigable land, 6,227 for cereals,[20] while 31 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[21]

Jordanian rule (1948–1967)

The old village, less than two kilometers northwest of the new town on the Israeli side of the Green Line, was captured by the Harel Brigade of the Palmach in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The village defense consisted of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and the Arab Liberation Army as well as a local militia. It was reclaimed by Arab forces more than once before it capitulated to Israeli troops on October 21, 1948.[3][22] Thousands of villagers fled. In the 1949 Armistice Agreements, the Green Line was drawn through the village with 70% of the land and 30 water springs on the Israeli side.[23]

The village was completely destroyed during the 1948 war and the villagers rebuilt it east of the 1949 Armistice Line inside the West Bank territories.[24]

In January 1952, an IDF patrol seized two Arab villagers in a field 300 meters on the Jordanian side of the armistice line and brought them to an abandoned house in Walaja, where they were killed. Israel told UN investigators that they had been shot inside Israeli territory when they had jumped out from behind a rock. The UN and Jordanian cross-examiners were unable to obtain an Israeli admission, but the Israeli delegate on the Mixed Armistice Commission wrote privately to his superior that the allegations were true but the patrol was not acting under orders.[25]

1967 and aftermath

After the Six-Day War in 1967, the whole of Al-Walaja has been under Israeli occupation.

Israel redrew the Jerusalem municipal boundaries, annexing half of al-Walaja's land that had remained after the 1948 war.[23] Although the Ain Jawaizeh neighborhood of al-Walaja was included in the Jerusalem Municipality, imposing Israeli law on its inhabitants, residency rights in Jerusalem were denied. Ain Jawaizeh does not receive municipal services and homes may not be built.[26][27] The splitting of the village caused various problems. Cars of local residents of both parts were confiscated by the Israeli Border Police for trespassing illegally into Israel.[27]

After the 1995 accords, 2.6% of al-Walaja land was classified as Area B, while the remaining 97.4% was classified as Area C. 45 and 92 dunams of village land were confiscated for the construction of Gilo and Har Gilo respectively.[23][28]

In 2003 through January 2005, Israel demolished Palestinian houses in Ain Jawaizeh and issued demolition orders against 53 other houses.[29] Land confiscation orders issued by the IDF in August 2003 showed that the route of the barrier will completely surround the residents of the village, allowing them only one entry/exit point. The two main access routes for Ain Jawaizeh to Bethlehem were both closed, and the only access road to Jerusalem was restricted for access to Har Gilo by Israeli-licensed vehicles only.[27] In April 2005, fruit orchards were cut down and homes were demolished due to the absence of building permits to make place for the construction of the barrier.[30]

In April 2010, Gush Etzion settlers and residents of al-Walaja united to protest the extension of security fences around Jerusalem. The event was partially coordinated by the Kfar Etzion-based organization ארצשלום ("Land of Peace") dedicated to building contacts between Jewish settlers and West Bank Arabs.[31]

In 2012, a group of Harvard students were expelled from al-Walaja when they tried to visit a house which was due to be demolished due to the West Bank wall.[32]

In September 2018, four houses built without planning permission were destroyed by Israeli border police, injuring about 40 people in the process.[33] Lawyer Itai Peleg representing some of the villagers wrote that Israel had for years refused to approve a master plan for the village and that "there is no dispute that the State of Israel and its various authorities and the Jerusalem municipality give the residents of al-Walaja no service whatsoever other than ‘home demolition service.’"[33]

Though technically their lands are incorporated into the Jerusalem municipality, the Israeli authorities have refused to issue most residents blue cards. The area is planned as a national park for residents of Gilo. Picking olives from their lands, divided from the adjacent village by the Separation Barrier, can require a roundabout 25 kilometer trek. In October 2019, on Walaja resident was fined $US200 for picking olives from his family land.[34]

Demography

According to a census by the British Mandate government in 1945, al-Walaja had a population of 1,650 inhabitants and a land area of 17,708 dunams.[1] The residents fled when it was captured and the Israeli village of Aminadav was built on the land. One of the few old-timers is Abed Rabbeh, who lives alone in a cave and raises chickens. When U.S. President Barack Obama was visiting Israel, Rabbeh invited him to his cave but the U.S. Consulate in Jerusalem sent a brief note of regret saying this could not be arranged.[35]

Landmarks

The village has three mosques.[36]

Al-Badawi-Boom, the ancient olive tree

Walaja is the site of Al-Badawi-Boom, an ancient olive tree claimed to be approximately 5,000-year-old and therefore the second oldest olive tree in the world after "The Sisters" olive trees in Bchaaleh, Northern Lebanon.[37][36]

'Ain el-Haniya spring

The 'Ain el-Haniya spring (also spelled Ein Haniya or Hanniya) in the Rephaim Valley, located on village lands, but separated from it by the West Bank barrier, flows from among the ruins of a Roman nymphaeum and boasts a number of archaeological remains. It has historically been used as a source of water for people and flocks, for irrigation and for recreation. Once restoration and development work has been completed in 2018, the site was reopened as part of the Refa'im Valley Park, but only Israelis were allowed access to it.[38][39][40] A Christian tradition places here the baptism of the royal Ethiopian treasurer by the deacon Philip, known as the Evangelist, and the ruins of a Byzantine church are standing next to the spring.[39]

ʿAin Joweizeh spring

'Ain Joweizeh is another spring in the immediate vicinity of Al-Walaja. During an archaeological survey in 'Ain Joweizeh, an ancient Judahite water system was found, together with a Proto-Aeolic capital.[41]

Cultural institutions

The Al-Walaja sports club was established in 1995. A women's club and the Ansar Youth Center opened in 2000. In 2005, the Ministry of the Interior established the Agriculture Charitable Society to aid local farmers.[36]

See also

References

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58 Archived 2018-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Palmer, 1881, p. 338

- Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #349. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 323

- 2007 PCBS Census Archived December 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. p.116

- David Dean Shulman, "On Being Unfree: Fences, Roadblocks and the Iron Cage of Palestine", Manoa Vol. 20, No. 2, 2008, pp. 13-32

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 116. Note typo, see talk−page

- Khalidi, 1992, p. 322

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 2, p. 325

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, Appendix 2, p. 123

- Socin, 1879, p. 163 Also noted it in the Beni Hasan district

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 122 also noted 78 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 22. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 322

- Macalister and Masterman, 1905, p. 353

- Schick, 1896, p. 125

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- Mills, 1932, p. 44

- Transformation in Arab Settlement, Moshe Brawer, in The Land that Became Israel: Studies in Historical Geography, Ruth Kark (ed), Magnes Press, Jerusalem 1989, p.177

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 104 Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 154 Archived 2014-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Khalidi, 1992, pp. 206-207

- Palestinians on statehood: ′We want action, not votes at the UN′. Harriet Sherwood, The Guardian, 14 September 2011

- Living in a Cage. POICA, 17 January 2004

- Morris, 1993, p. 183

- The Israeli Colonization Activities in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip During 2004, section "Case Study 1(a): Al Walaja Village". ARIJ, March 2005

- OCHA Humanitarian Update Occupied Palestinian Territories Jan 2005. ReliefWeb, 31 January 2005

- Al Walaja Village Profile, p. 16

- At Risk of De-Population: Home Demolitions in Ain Jawaizeh area of Al-Walaja Village, Bethlehem Governorate Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine. PLO-NAD, Palestinian Monitoring Group, 18 January 2005

- Israeli Authorities Cut Down Hundreds of Fruit-Bearing Trees. PLO-NAD, Palestinian Monitoring Group, 14 April 2005

- 'Settlers and Palestinians may unite'

- Israel Police expel Harvard students from Palestinian village, Mar. 14, 2012, Haaretz

- Nir Hasson (2018-09-03). "Israel Demolishes Buildings in Palestinian Village; 10 Wounded". Haaretz.

- Gideon Levy, Alex Levac, Israel Is Turning an Ancient Palestinian Village Into a National Park for Settlers(archive), Haaretz 25 October 2019

- "I can't live without this place" March 3, 2010

- Al Walaja religious and archaeological sites

- "8 Oldest Olive Trees in History". www.oldest.org/. Oldest.org. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- The Jerusalem Municipality Opens a Spring for Israelis Only, Peace Now, 19 February 2018, accessed 4 September 2020.

- The Ein Hanya Spring: A Charming, Spruced-up Jerusalem Spot Free of Palestinians, by Naama Riba, for Haaretz, 16 March 2018, accessed 4 September 2020.

- orests-and-parks/jeruslem-park.aspx Refa'im Valley Park, at "Jerusalem Metropolitan Park - A Green Lung for Israel's Capital" on the Jewish National Fund website. Accessed 4 September 2020.

- Ein Mor, Daniel; Ron, Zvi (2 July 2016). "ʿAin Joweizeh: An Iron Age Royal Rock-Cut Spring System in the Naḥal Refa'im Valley, near Jerusalem". Tel Aviv. 43 (2): 127–146. doi:10.1080/03344355.2016.1215531. ISSN 0334-4355. S2CID 132786721.

Bibliography

- Baramki, D.C. (1934). "An early Christian Basilica at 'Ain Hanniya". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 3: 113–117.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (visited 1863: pp. 5, 385: Oueledjeh)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Macalister, R.A.S.; Masterman, E.W.G. (1905). "Occasional Papers on the Modern Inhabitants of Palestine, part I & part II". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 37: 343–356.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1993). Israel's Border Wars, 1949-1956: Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829262-3.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To al-Walaja, PalestineRemembered.com (old page, archived)

- Welcome To al-Walaja, PalestineRemembered.com (new page, accessed September 2020)

- al-Walaja, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Al Walaja Village (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ)

- Al Walaja Village Profile, ARIJ

- Al Walaja aerial photo, ARIJ

- The priorities and needs for development in Al Walaja village based on the community and local authorities’ assessment, ARIJ

- al-Walaja, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Palestinian statehood: The olive tree of al-Walaja - video

- Olive Wars, 2014, BBC