Amish

The Amish (/ˈɑːmɪʃ/; Pennsylvania German: Amisch; German: Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins.[2] They are closely related to Mennonite churches, a separate Anabaptist denomination.[3] The Amish are known for simple living, plain dress, Christian pacifism, and slowness to adopt many conveniences of modern technology, with a view neither to interrupt family time, nor replace face-to-face conversations whenever possible, and a view to maintain self-sufficiency. The Amish value rural life, manual labor, humility and Gelassenheit (submission to God's will).

An Amish family riding in a traditional Amish buggy in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 383,565 (2023, Old Order Amish)[1] | |

| Founder | |

| Jakob Ammann | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (large populations in Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania; notable populations in Kentucky, Missouri, Michigan, New York, and Wisconsin; small populations in various other states) Canada (mainly in Ontario) | |

| Religions | |

| Anabaptist | |

| Scriptures | |

| The Bible | |

| Languages | |

| Pennsylvania Dutch, Bernese German, Low Alemannic Alsatian German, Amish High German, English |

| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Amish church began with a schism in Switzerland within a group of Swiss and Alsatian Mennonite Anabaptists in 1693 led by Jakob Ammann.[4] Those who followed Ammann became known as Amish.[5] In the second half of the 19th century, the Amish divided into Old Order Amish and Amish Mennonites; the latter do not abstain from using motor cars, whereas the Old Order Amish retained much of their traditional culture. When people refer to the Amish today, they normally refer to the Old Order Amish, though there are other subgroups of Amish. In the early 18th century, many Amish and Mennonites immigrated to Pennsylvania for a variety of reasons. Today, the Old Order Amish, the New Order Amish, and the Old Beachy Amish as well as Old Order Mennonites continue to speak Pennsylvania Dutch, although two different Alemannic dialects are used by Old Order Amish in Adams and Allen counties in Indiana.[6] As of 2023, over 377,000 Old Order Amish lived in the United States, and about 6,000 lived in Canada: a population that is rapidly growing, even though most Amish clearly seem to use some form of birth control, a fact that generally is not discussed among the Amish. This is indicated by the fact that the number of children systematically increases in correlation with the conservatism of a congregation: the more conservative, the more children.[7] Amish church groups seek to maintain a degree of separation from the non-Amish world. Non-Amish people are generally referred to as "English" by the Amish, and outside influences are often described as "worldly".

Amish church membership begins with adult baptism, usually between the ages of 16 and 23. Church districts have between 20 and 40 families, and worship services are held every other Sunday in a member's home or barn. The rules of the church, the Ordnung, which differs to some extent between different districts, are reviewed twice a year by all members of the church. The Ordnung must be observed by every member and covers many aspects of day-to-day living, including prohibitions or limitations on the use of power-line electricity, telephones, and automobiles, as well as regulations on clothing. Generally, a heavy emphasis is placed on church and family relationships. The Amish typically operate their own one-room schools and discontinue formal education after grade eight (age 13 – 14). Most Amish do not buy commercial insurance or participate in Social Security. As present-day Anabaptists, Amish church members practice nonresistance and will not perform any type of military service.[8]

History

Beginnings of Anabaptist Christianity

The Anabaptist movement, from which the Amish later emerged, started in circles around Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) who led the early Reformation in Switzerland. In Zürich on January 21, 1525, Conrad Grebel and George Blaurock practiced believer's baptism to each other and then to others.[9] This Swiss movement, part of the Radical Reformation, later became known as Swiss Brethren.[10]

Emergence of the Amish

The term Amish was first used as a Schandename (a term of disgrace) in 1710 by opponents of Jakob Amman, an Anabaptist leader. The first informal division between Swiss Brethren was recorded in the 17th century between Oberländers (those living in the hills) and Emmentalers (those living in the Emmental ). The Oberländers were a more extreme congregation; their zeal pushed them into more remote areas.

Swiss Anabaptism developed, from this point, in two parallel streams, most clearly marked by disagreement over the preferred treatment of "fallen" believers. The Emmentalers (sometimes referred to as Reistians, after bishop Hans Reist, a leader among the Emmentalers) argued that fallen believers should only be withheld from communion, and not regular meals. The Amish argued that those who had been banned should be avoided even in common meals. The Reistian side eventually formed the basis of the Swiss Mennonite Conference. Because of this common heritage, Amish and conservative Mennonites from southern Germany and Switzerland retain many similarities. Those who leave the Amish fold tend to join various congregations of Conservative Mennonites.[11][12]

Migration to North America

Amish began migrating to Pennsylvania, then-regarded favorably due to the lack of religious persecution and attractive land offers, in the early 18th century as part of a larger migration from the Palatinate and neighboring areas. Between 1717 and 1750, approximately 500 Amish migrated to North America, mainly to the region that became Berks County, Pennsylvania, but later moved, motivated by land issues and by security concerns tied to the French and Indian War. Many eventually settled in Lancaster County. A second wave of around 1,500 arrived around the mid-19th century and settled mostly in Ohio, Illinois, Iowa and southern Ontario. Most of these late immigrants eventually did not join the Old Order Amish but more liberal groups.[13]

1850–1878 Division into Old Orders and Amish Mennonites

Most Amish communities that were established in North America did not ultimately retain their Amish identity. The major division that resulted in the loss of identity of many Amish congregations occurred in the third quarter of the 19th century. The forming of factions worked its way out at different times at different places. The process was rather a "sorting out" than a split. Amish people are free to join another Amish congregation at another place that fits them best.

In the years after 1850, tensions rose within individual Amish congregations and between different Amish congregations. Between 1862 and 1878, yearly Dienerversammlungen (ministerial conferences) were held at different places, concerning how the Amish should deal with the tensions caused by the pressures of modern society.[14] The meetings themselves were a progressive idea; for bishops to assemble to discuss uniformity was an unprecedented notion in the Amish church. By the first several meetings, the more traditionally minded bishops agreed to boycott the conferences.

The more progressive members, comprising roughly two-thirds of the group, became known by the name Amish Mennonite, and eventually united with the Mennonite Church, and other Mennonite denominations, mostly in the early 20th century. The more traditionally minded groups became known as the Old Order Amish.[15] The Egli Amish had already started to withdraw from the Amish church in 1858. They soon drifted away from the old ways and changed their name to "Defenseless Mennonite" in 1908.[16] Congregations who took no side in the division after 1862 formed the Conservative Amish Mennonite Conference in 1910, but dropped the word "Amish" from their name in 1957; in the year 2000 many congregations left to organize the Biblical Mennonite Alliance in order to continue the practice of traditional Anabaptist ordinances, such as headcovering.[17][18]

Because no division occurred in Europe, the Amish congregations remaining there took the same way as the change-minded Amish Mennonites in North America and slowly merged with the Mennonites. The last Amish congregation in Germany to merge was the Ixheim Amish congregation, which merged with the neighboring Mennonite Church in 1937. Some Mennonite congregations, including most in Alsace, are descended directly from former Amish congregations.[19][20]

20th century

Though splits happened among the Old Order in the 19th century in Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, a major split among the Old Orders took until World War I. At that time, two very conservative affiliations emerged – the Swartzentruber Amish in Holmes County, Ohio, and the Buchanan Amish in Iowa. The Buchanan Amish soon were joined by like-minded congregations all over the country.[21]

With World War I came the massive suppression of the German language in the US that eventually led to language shift of most Pennsylvania German speakers, leaving the Amish and other Old Orders as almost the only speakers by the end of the 20th century. This created a language barrier around the Amish that did not exist before in that form.[22]

In the late 1920s, the more change minded faction of the Old Order Amish, that wanted to adopt the car, broke away from the mainstream and organized under the name Beachy Amish.[23]

During the Second World War, the old question of military service for the Amish came up again. Because Amish young men in general refused military service, they ended up in the Civilian Public Service (CPS), where they worked mainly in forestry and hospitals. The fact that many young men worked in hospitals, where they had a lot of contact with more progressive Mennonites and the outside world, had the result that many of these men never joined the Amish church.[24]

In the 1950s, the Beachy Amish, as with the New Order Amish, laid heavy emphasis on the New Birth, personal holiness and Sunday School education.[25][26] The ones who wanted to preserve the old way of the Beachy became the Old Beachy Amish.[23]

Until about 1950, almost all Amish children attended small, rural, non-Amish schools, but then school consolidation and mandatory schooling beyond eighth grade caused Amish opposition. Amish communities opened their own Amish schools. In 1972, the United States Supreme Court exempted Amish pupils from compulsory education past eighth grade. By the end of the 20th century, almost all Amish children attended Amish schools.[27]

In the last quarter of the 20th century, a growing number of Amish men left farm work and started small businesses because of increasing pressure on small-scale farming. Though a wide variety of small businesses exists among the Amish, construction work and woodworking are quite widespread.[28] In many Amish settlements, especially the larger ones, farmers are now a minority.[29] Approximately 12,000 of the 40,000 dairy farms in the United States are Amish-owned as of 2018.[30][31]

Until the early 20th century, Old Order Amish identity was not linked to the limited use of technologies, as the Old Order Amish and their rural neighbors used the same farm and household technologies. Questions about the use of technologies also did not play a role in the Old Order division of the second half of the 19th century. Telephones were the first important technology that was rejected, soon followed by the rejection of cars, tractors, radios, and many other technological inventions of the 20th century.[32]

Old Order Mennonites, Old Colony Mennonites and the Amish are often grouped together in North America's popular press. This is incorrect, according to a 2017 report by Canadian Mennonite magazine:[33]

The customs of Old Order Mennonites, the Amish communities and Old Colony Mennonites have a number of similarities, but the cultural differences are significant enough so that members of one group would not feel comfortable moving to another group. The Old Order Mennonites and Amish have the same European roots and the language spoken in their homes is the same German dialect. Old Colony Mennonites use Low German, a different German dialect.

Religious practices

Two key concepts for understanding Amish practices are their rejection of Hochmut (pride, arrogance, haughtiness) and the high value they place on Demut (humility) and Gelassenheit (calmness, composure, placidity), often translated as "submission" or "letting be". Gelassenheit is perhaps better understood as a reluctance to be forward, to be self-promoting, or to assert oneself. The Amish's willingness to submit to the "Will of Jesus", expressed through group norms, is at odds with the individualism so central to the wider American culture. The Amish anti-individualist orientation is the motive for rejecting labor-saving technologies that might make one less dependent on the community. Modern innovations such as electricity might spark a competition for status goods, or photographs might cultivate personal vanity. Electric power lines would be going against the Bible, which says that you shall not be "conformed to the world" (Romans 12:2).

Amish church membership begins with baptism, usually between the ages of 16 and 23. It is a requirement for marriage within the Amish church. Once a person is baptized within the church, he or she may marry only within the faith. Church districts have between 20 and 40 families and worship services are held every other Sunday in a member's home or barn. The district is led by a bishop and several ministers and deacons who are chosen by a combination of election and cleromancy (lot).[34]

The rules of the church, the so-called Ordnung, which differs to some extent between different districts, is reviewed twice a year by all members of the church. Only if all members give their consent to it, Lord's supper is held. The Ordnung must be observed by every member and covers many aspects of day-to-day living, including prohibitions or limitations on the use of power-line electricity, telephones, and automobiles, as well as regulations on clothing. As present-day Anabaptists, Amish church members practice nonresistance and will not perform any type of military service. The Amish value rural life, manual labor, humility, and Gelassenheit, all under the auspices of living what they interpret to be God's word.

Members who do not conform to these community expectations and who cannot be convinced to repent face excommunication and shunning. The modes of shunning vary between different communities.[35] On average, about 85 percent of Amish youth choose to be baptized and join the church.[36] During an adolescent period of rumspringa (dialectal [Pennsylvania] German for "around running") in some communities, nonconforming behavior that would result in the shunning of an adult who had made the permanent commitment of baptism, may be met with a degree of forbearance.[37]

Way of life

Amish lifestyle is regulated by the Ordnung ("rules")[38] which differs slightly from community to community and from district to district within a community. There is no central Amish governing authority, so each individual community makes its own decisions, and what is acceptable in one community may not be acceptable in another.[39] The Ordnung is agreed upon – or changed – within the whole community of baptized members prior to Communion which takes place two times a year. The meeting where the Ordnung is discussed is called Ordnungsgemeine in Standard German and Ordningsgmee in Pennsylvania Dutch. The Ordnung include matters such as dress, permissible uses of technology, religious duties, and rules regarding interaction with outsiders. In these meetings, women also vote in questions concerning the Ordnung.[40]

Bearing children, raising them, and socializing with neighbors and relatives are the greatest functions of the Amish family. Amish typically believe that large families are a blessing from God. Farm families tend to have larger families, because sons are needed to perform farm labor.[41] Community is central to the Amish way of life.

Working hard is considered godly, and some technological advancements have been considered undesirable because they reduce the need for hard work. Machines such as automatic floor cleaners in barns have historically been rejected as this provides young farmhands with too much free time.[42]

Transportation

Amish communities are known for traveling by horse and buggy because they feel horse-drawn carriages promote a slow pace of life. But most Amish communities do also allow riding in motor vehicles, such as buses and cars.[43] In recent years many Amish people have taken to using electric bicycles because they are faster than either walking or harnessing up a horse and buggy.[39]

Clothing

The Amish are known for their plain attire. Men wear solid colored shirts, broad-brimmed hats, and suits that signify similarity amongst one another. Amish men grow beards to symbolize manhood and marital status, as well as to promote humility. They are forbidden to grow mustaches because mustaches are seen by the Amish as being affiliated with the military, which they are strongly opposed to, due to their pacifist beliefs. Women have similar guidelines on how to dress, which are also expressed in the Ordnung, the Amish version of legislation. They are to wear calf-length dresses, muted colors along with bonnets and aprons. Prayer kapps and bonnets are worn by the women because they are a visual representation of their religious beliefs and promote unity through the tradition of every woman wearing one. The color of the bonnet signifies whether a woman is single or married. Single women wear black bonnets and married women wear white. The color coding of bonnets is important because women are not allowed to wear jewelry, such as wedding rings, as it is seen as drawing attention to the body which can induce pride in the individual.[44] All clothing is sewn by hand, but the way to fasten the garment widely depends on whether the Amish person is a part of the New Order or Old Order Amish.[45] The Old Order Amish seldom, if ever, use buttons because they are seen as too flashy; instead, they use the hook and eye approach to fashion clothing or metal snaps. The New Order Amish are slightly more progressive and allow the usage of buttons to help attire clothing.

Cuisine

Amish cuisine is noted for its simplicity and traditional qualities. Food plays an important part in Amish social life and is served at potlucks, weddings, fundraisers, farewells, and other events.[46][47][48][49] Many Amish foods are sold at markets including pies, preserves, bread mixes, pickled produce, desserts, and canned goods. Many Amish communities have also established restaurants for visitors. Amish meat consumption is similar to the American average though they tend to eat more preserved meat.[50]

Amish cuisine is often mistaken for the similar cuisine of the Pennsylvania Dutch with some ethnographic and regional variances,[51] as well as differences in what cookbook writers and food historians emphasize about the traditional foodways and intertwined religious culture and celebrations of Amish communities. While mythologies about the diffusion of shoofly pie are common subject matter for studies of American cuisine, food anthropologists point out that the culinary practices of Pennsylvania Dutch and Amish are innovative and dynamic, evolving across time and geographical spaces, and that not all the Pennsylvania Dutch are Amish, and not all Amish live in Pennsylvania. Distinguishing local mythologies from culinary fact is accomplished by dedicated anthropological field studies in combination with studies of literary sources, usually newspaper archives, diaries and household records.[52]

Subgroups

Over the years, the Amish churches have divided many times mostly over questions concerning the Ordnung, but also over doctrinal disputes, mainly about shunning. The largest group, the "Old Order" Amish, a conservative faction that separated from other Amish in the 1860s, are those who have most emphasized traditional practices and beliefs. The New Order Amish are a group of Amish whom some scholars see best described as a subgroup of Old Order Amish, despite the name.

Affiliations

As of 2011, about 40 different Old Order Amish affiliations were known to exist. The eight major affiliations are listed below, with Lancaster as the largest one in number of districts and population:[53]

| Affiliation | Date established | Origin | States | Settlements | Church districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lancaster | 1760 | Pennsylvania | 8 | 37 | 291 |

| Elkhart-LaGrange | 1841 | Indiana | 3 | 9 | 176 |

| Holmes Old Order | 1808 | Ohio | 1 | 2 | 147 |

| Buchanan/Medford | 1914 | Indiana | 19 | 67 | 140 |

| Geauga I | 1886 | Ohio | 6 | 11 | 113 |

| Swartzentruber | 1913 | Ohio | 15 | 43 | 119 |

| Geauga II | 1962 | Ohio | 4 | 27 | 99 |

| Swiss (Adams) | 1850 | Indiana | 5 | 15 | 86 |

Use of technology by different affiliations

The table below indicates the use of certain technologies by different Amish affiliations. The use of cars is not allowed by any Old and New Order Amish, nor are radio, television, or in most cases the use of the Internet. Three affiliations – "Lancaster", "Holmes Old Order" and "Elkhart-LaGrange" — are not only the three largest affiliations but also represent the mainstream among the Old Order Amish. The most conservative affiliations are at the top, the most modern ones at the bottom. Technologies used by very few are on the left; the ones used by most are on the right. The percentage of all Amish who use a technology is also indicated approximately. The Old Order Amish culture involves lower greenhouse gas emissions in all sectors and activities with the exception of diet, and their per-person emissions has been estimated to be less than one quarter that of the wider society.[54]

| Affiliation[55] | Tractor for fieldwork | Roto- tiller | Power lawn mower | Propane gas | Bulk milk tank | Mechanical milker | Mechanical refrigerator | Pickup balers | Inside flush toilet | Running water bath tub | Tractor for belt power | Pneumatic tools | Chain saw | Pressurized lamps | Motorized washing machines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swartzentruber | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Some | No | No | Yes |

| Nebraska | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Some | No | No | No | No | Some | No | Yes |

| Swiss (Adams) | No | No | Some | No | No | No | No | No | Some | No | No | Some | Some | Some | Some |

| Buchanan/Medford | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Some | No | Yes | Yes |

| Danner | No | No | No | Some | No | No | Some | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Geauga I | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Some | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Holmes Old Order | No | Some | Some | No | No | No | Some | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Elkhart-LaGrange | No | Some | Some | Some | Some | Some | Some | Some | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lancaster | No | No | Some | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nappanee | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kalona | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Percentage of use by all Amish |

6 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 50 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 75 | 90 | 97 |

Language

Most Old Order Amish speak Pennsylvania Dutch, and refer to non-Amish people as "English", regardless of ethnicity.[56] Two Amish subgroups – called Swiss Amish – whose ancestors migrated to the United States in the 1850s speak a form of Bernese German (Adams County, IN and daughter settlements) or a Low Alemannic Alsatian dialect (Allen County, IN and daughter settlements).[57]

Contrary to popular belief, the word "Dutch" in "Pennsylvania Dutch" is not a mistranslation, but rather a corruption of the Pennsylvania German endonym Deitsch, which means "Pennsylvania Dutch / German" or "German".[58][59][60][61] Ultimately, the terms Deitsch, Dutch, Diets and Deutsch are all cognates and descend from the Proto-Germanic word *þiudiskaz meaning "popular" or "of the people".[62] The continued use of "Pennsylvania Dutch" was strengthened by the Pennsylvania Dutch in the 19th century as a way of distinguishing themselves from later (post 1830) waves of German immigrants to the United States, with the Pennsylvania Dutch referring to themselves as Deitsche and to Germans as Deitschlenner (literally "Germany-ers", compare Deutschländ-er) whom they saw as a related but distinct group.[63]

According to one scholar, "today, almost all Amish are functionally bilingual in Pennsylvania Dutch and English; however, domains of usage are sharply separated. Pennsylvania Dutch dominates in most in-group settings, such as the dinner table and preaching in church services. In contrast, English is used for most reading and writing. English is also the medium of instruction in schools and is used in business transactions and often, out of politeness, in situations involving interactions with non-Amish. Finally, the Amish read prayers and sing in Standard German (which, in Pennsylvania Dutch, is called Hochdeitsch[lower-alpha 1]) at church services. The distinctive use of three different languages serves as a powerful conveyor of Amish identity.[64] "Although 'the English language is being used in more and more situations,' Pennsylvania Dutch is 'one of a handful of minority languages in the United States that is neither endangered nor supported by continual arrivals of immigrants.'"[65]

Ethnicity

The Amish largely share a German or Swiss-German ancestry.[66] They generally use the term "Amish" only for members of their faith community and not as an ethnic designation. However some Amish descendants recognize their cultural background knowing that their genetic and cultural traits are uniquely different from other ethnicities.[67][68] Those who choose to affiliate with the church, or young children raised in Amish homes, but too young to yet be church members, are considered to be Amish. Certain Mennonite churches have a high number of people who were formerly from Amish congregations. Although more Amish immigrated to North America in the 19th century than during the 18th century, most of today's Amish descend from 18th-century immigrants. The latter tended to emphasize tradition to a greater extent, and were perhaps more likely to maintain a separate Amish identity.[69] There are a number of Amish Mennonite church groups that had never in their history been associated with the Old Order Amish because they split from the Amish mainstream in the time when the Old Orders formed in the 1860s and 1870s. The former Western Ontario Mennonite Conference (WOMC) was made up almost entirely of former Amish Mennonites who reunited with the Mennonite Church in Canada.[70] Orland Gingerich's book The Amish of Canada devotes the vast majority of its pages not to the Beachy or Old Order Amish, but to congregations in the former WOMC.

Para-Amish groups

Several other groups, called "para-Amish" by G. C. Waldrep and others, share many characteristics with the Amish, such as horse and buggy transportation, plain dress, and the preservation of the German language. The members of these groups are largely of Amish origin, but they are not in fellowship with other Amish groups because they adhere to theological doctrines (e.g., assurance of salvation) or practices (community of goods) that are normally not accepted among mainstream Amish. The Bergholz Community is a different case, it is not seen as Amish anymore because the community has shifted away from many core Amish principles.

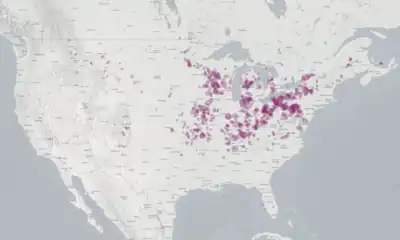

Population and distribution

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 5,000 | — |

| 1928 | 7,000 | +4.30% |

| 1936 | 9,000 | +3.19% |

| 1944 | 13,000 | +4.70% |

| 1952 | 19,000 | +4.86% |

| 1960 | 28,000 | +4.97% |

| 1968 | 39,000 | +4.23% |

| 1976 | 57,000 | +4.86% |

| 1984 | 84,000 | +4.97% |

| 1992 | 128,150 | +5.42% |

| 2000 | 166,000 | +3.29% |

| 2010 | 249,500 | +4.16% |

| 2020 | 350,665 | +3.46% |

| 2023 | 383,565 | +3.03% |

| Source: 1992,[71] 2000,[72] 2010,[73] 2020,[74] 2021,[75] 2023[1] | ||

Because the Amish are usually baptized no earlier than 18 and children are not counted in local congregation numbers, estimating their numbers is difficult. Rough estimates from various studies placed their numbers at 125,000 in 1992, 166,000 in 2000, and 221,000 in 2008.[72] Thus, from 1992 to 2008, population growth among the Amish in North America was 84 percent (3.6 percent per year). During that time, they established 184 new settlements and moved into six new states.[76] In 2000, about 165,620 Old Order Amish resided in the United States, of whom 73,609 were church members.[77] The Amish are among the fastest-growing populations in the world, with an average of seven children per family in the 1970s[78] and a total fertility rate of 5.3 in the 2010s.[79]

In 2010, a few religious bodies, including the Amish, changed the way their adherents were reported to better match the standards of the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. When looking at all Amish adherents and not solely Old Order Amish, about 241,000 Amish adherents were in 28 U.S. states in 2010.[80]

United States

| State | 1992 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania | 32,710 | 44,620 | 59,350 | 81,500 | 88,850 |

| Ohio | 34,830 | 48,545 | 58,590 | 78,280 | 84,065 |

| Indiana | 23,400 | 32,840 | 43,710 | 59,305 | 63,645 |

| Wisconsin | 6,785 | 9,390 | 15,360 | 22,235 | 24,920 |

| New York | 4,050 | 4,505 | 12,015 | 21,230 | 23,285 |

| Michigan | 5,150 | 8,495 | 11,350 | 16,525 | 18,445 |

| Missouri | 3,745 | 5,480 | 9,475 | 14,520 | 16,690 |

| Kentucky | 2,625 | 4,850 | 7,750 | 13,595 | 15,450 |

| Iowa | 3,525 | 4,445 | 7,190 | 9,780 | 9,930 |

The United States is the home to the overwhelming majority (98 percent) of the Amish people. In 2023, Old Order communities were present in 32 U.S. states. The total Amish population in the United States as of June 2023 has stood at 377,300[1] up 9,975 or 2.7 percent, compared to the previous year. Pennsylvania has the largest population (89 thousand), followed by Ohio (84 thousand) and Indiana (63.6 thousand), as of June 2023.[81] The largest Amish settlements are in Lancaster County in southeastern Pennsylvania (43,400), Holmes County and adjacent counties in northeastern Ohio (39,525), and Elkhart and LaGrange counties in northeastern Indiana (28,275), as of June 2023.[1] The highest concentration of Amish in the world is in the Holmes County community; nearly 50 percent of the entire population of Holmes County is Amish as of 2010.[82]

The largest concentration of Amish west of the Mississippi River is in Missouri, with other settlements in eastern Iowa and southeast Minnesota.[83] The largest Amish settlements in Iowa are located near Kalona and Bloomfield.[84] The largest settlement in Wisconsin is near Cashton with 13 congregations, i.e. about 2,000 people in 2009.[85]

Because of the rapid population growth of the Amish communities, new settlements in the United States are being established each year, thus: 18 new settlements were established in 2016, 24 in 2017, 18 in 2018, 27 in 2019, 26 in 2020, 19 in 2021, 15 in 2022 and 10 by June 2023.[86][74][81][1] The main reason for the continuous expansion is to obtain enough affordable farmland, other reasons for new settlements include locating in isolated areas that support their lifestyle, moving to areas with cultures conducive to their way of life, maintaining proximity to family or other Amish groups, and sometimes to resolve church or leadership conflicts.[76]

The adjacent table shows the eight states with the largest Amish population in the years 1992, 2000, 2010, 2020 and 2023.[87][42][88][89][74][1]

Canada

| Canada | 1992 | 2010 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All of Canada | 2,295 | 4,725 | 5,995 | 6,100 |

| Ontario | 2,295 | 4,725 | 5,605 | 5,645 |

| Prince Edward Isl. | 0 | 0 | 250 | 280 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | 70 | 95 |

| Manitoba | 0 | 0 | 70 | 80 |

Amish settlements are in four Canadian provinces: Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and New Brunswick. The majority of Old Order settlements is located in the province of Ontario, namely Oxford (Norwich Township) and Norfolk Counties. A small community is also established in Bruce County (Huron-Kinloss Township) near Lucknow.

In 2016, several dozen Old Order Amish families founded two new settlements in Kings County in the province of Prince Edward Island. Increasing land prices in Ontario had reportedly limited the ability of members in those communities to purchase new farms.[90] At about the same time a new settlement was founded near Perth-Andover in New Brunswick, only about 12 km (7.5 mi) from Amish settlements in Maine. In 2017, an Amish settlement was founded in Manitoba near Stuartburn.[91]

Latin America

| Country | 2010 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bolivia | 0 | 160 | 190 |

| Argentina | 0 | 50 | 0 |

There are currently two Amish settlements in South American nations: Argentina and Bolivia. The majority of Old Order settlements are located in Bolivia. The first attempt by Old Order Amish to settle in Latin America was in Paradise Valley, near Galeana, Nuevo León, Mexico, but the settlement lasted from only 1923 to 1929.[19] An Amish settlement was tried in Honduras from about 1968 to 1978, but this settlement failed too.[92] In 2015, new settlements of New Order Amish were founded east of Catamarca, Argentina, and Colonia Naranjita, Bolivia, about 75 miles (121 km) southwest of Santa Cruz.[93] Most of the members of these new communities come from Old Colony Mennonite background and have been living in the area for several decades.[94]

Europe

In Europe, no split occurred between Old Order Amish and Amish Mennonites; like the Amish Mennonites in North America, the European Amish assimilated into the Mennonite mainstream during the second half of the 19th century through the first decades of the 20th century. Eventually, they dropped the word "Amish" from the names of their congregations and lost their Amish identity and culture. The last European Amish congregation joined the Mennonites in 1937 in Ixheim, today part of Zweibrücken in the Palatinate region.[95]

Seekers and joiners

Only a few hundred outsiders, so-called seekers, have ever joined the Old Order Amish.[96] Since 1950, only some 75 non-Anabaptist people have joined and remained lifelong members of the Amish.[97] Since 1990, some twenty people of Russian Mennonite background have joined the Amish in Aylmer, Ontario.[98]

Two whole Christian communities have joined the Amish: The church at Smyrna, Maine, one of the five Christian Communities of Elmo Stoll after Stoll's death[99][100] and the church at Manton, Michigan, which belonged to a community that was founded by Harry Wanner (1935–2012), a minister of Stauffer Old Order Mennonite background.[101] The "Michigan Amish Churches", with which Smyrna and Manton affiliated, are said to be more open to seekers and converts than other Amish churches. Most of the members of these two para-Amish communities originally came from Plain churches, i.e. Old Order Amish, Old Order Mennonite, or Old German Baptist Brethren.

More people have tested Old Order Amish life for weeks, months, or even years, but in the end decided not to join. Others remain close to the Amish, but never think of joining.[97]

On the other hand, the Beachy Amish, many of whom conduct their services in English and allow for a limited range of modern conveniences, regularly receive seekers into their churches as visitors, and eventually, as members.[102][103]

Stephen Scott, himself a convert to the Old Order River Brethren, distinguishes four types of seekers:

- Checklist seekers are looking for a few certain specifications.

- Cultural seekers are more enchanted with the lifestyle of the Amish than with their religion.

- Spiritual utopian seekers are looking for true New Testament Christianity.

- Stability seekers come with emotional issues, often from dysfunctional families.[98]

Health

Amish populations have higher incidences of particular conditions, including dwarfism,[104] Angelman syndrome,[105] and various metabolic disorders,[106] as well as an unusual distribution of blood types.[107] The Amish represent a collection of different demes or genetically closed communities.[108] Although the Amish do not have higher incidence of genetic disorders than the general population,[109] since almost all Amish descend from a few hundred 18th-century founders, some recessive conditions are more prevalent (an example of the founder effect).[110][111][112] Some of these disorders are rare or unique, and are serious enough to increase the mortality rate among Amish children. The Amish are aware of the advantages of exogamy, but for religious reasons, marry only within their communities.[113] The majority of Amish accept these as Gottes Wille (God's will); they reject the use of preventive genetic tests prior to marriage and genetic testing of unborn children to discover genetic disorders. When children are born with a disorder, they are accepted into the community and tasked with chores within their ability.[114] However, Amish are willing to participate in studies of genetic diseases.[112] Their extensive family histories are useful to researchers investigating diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and macular degeneration.

While the Amish are at an increased risk for some genetic disorders, researchers have found their tendency for clean living can lead to better health. Overall cancer rates in the Amish are reduced and tobacco-related cancers in Amish adults are 37 percent and non-tobacco-related cancers are 72 percent of the rate for Ohio adults. Skin cancer rates are lower for Amish, even though many Amish make their living working outdoors where they are exposed to sunlight. They are typically covered and dressed by wearing wide-brimmed hats and long sleeves which protect their skin.[115]

Treating genetic problems is the mission of Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, which has developed effective treatments for such problems as maple syrup urine disease, a previously fatal disease. The clinic is embraced by most Amish, ending the need for parents to leave the community to receive proper care for their children, an action that might result in shunning. Another clinic is DDC Clinic for Special Needs Children, located in Middlefield, Ohio, for special-needs children with inherited or metabolic disorders.[116] The DDC Clinic provides treatment, research, and educational services to Amish and non-Amish children and their families.

People's Helpers is an Amish-organized network of mental health caregivers who help families dealing with mental illness and recommend professional counselors.[117] Suicide rates for the Amish are about half that of the general population.[lower-alpha 2]

The Old Order Amish do not typically carry private commercial health insurance.[119][120] A handful of American hospitals, starting in the mid-1990s, created special outreach programs to assist the Amish. In some Amish communities, the church will collect money from its members to help pay for medical bills of other members.[114] Although the Amish are often perceived by outsiders as rejecting all modern technologies, this is not the case and modern medicine is employed by Amish communities, including hospital births and other advanced treatments. As they go without health insurance and pay up front for services, Amish individuals will often travel to Mexico for non-urgent care and surgery to reduce costs.[121][122]

Most Amish clearly seem to use some form birth control, a fact that generally is not discussed among the Amish, but indicated by the fact that the number of children systematically increases in correlation with the conservatism of a congregation, the more conservative, the more children. The large number of children is due to the fact that many children are appreciated by the community and not because there is no birth control.[123] Some communities openly allow access to birth control to women whose health would be compromised by childbirth.[114] The Amish are against abortion and also find "artificial insemination, genetics, eugenics, and stem cell research" to be "inconsistent with Amish values and beliefs".[124]

Life in the modern world

As time has passed, the Amish have felt pressures from the modern world. Issues such as taxation, education, law and its enforcement, and occasional discrimination and hostility are areas of difficulty.

The modern way of life in general has increasingly diverged from that of Amish society. On occasion, this has resulted in sporadic discrimination and hostility from their neighbors, such as throwing of stones or other objects at Amish horse-drawn carriages on the roads.[125][126][127]

The Amish do not usually educate their children past the eighth grade, believing that the basic knowledge offered up to that point is sufficient to prepare one for the Amish lifestyle. Almost no Amish go to high school and college. In many communities, the Amish operate their own schools, which are typically one-room schoolhouses with teachers (usually young, unmarried women) from the Amish community. On May 19, 1972, Jonas Yoder and Wallace Miller of the Old Order Amish, and Adin Yutzy of the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church were each fined $5 for refusing to send their children, aged 14 and 15, to high school. In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned the conviction,[128] and the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this, finding the benefits of universal education were not sufficient justification to overcome scrutiny under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.[129]

The Amish are subject to sales and property taxes. As they seldom own motor vehicles, they rarely have occasion to pay motor vehicle registration fees or spend money on the purchase of fuel for vehicles.[130] Under their beliefs and traditions, generally the Amish do not agree with the idea of Social Security benefits and have a religious objection to insurance.[131][132] On this basis, the United States Internal Revenue Service agreed in 1961 that they did not need to pay Social Security-related taxes. In 1965, this policy was codified into law.[133] Self-employed individuals in certain sects do not pay into or receive benefits from the United States Social Security system. This exemption applies to a religious group that is conscientiously opposed to accepting benefits of any private or public insurance, provides a reasonable level of living for its dependent members, and has existed continuously since December 31, 1950.[134] The U.S. Supreme Court clarified in 1982 that Amish employers are not exempt, but only those Amish individuals who are self-employed.[135]

Publishing

In 1964, Pathway Publishers was founded by two Amish farmers to print more material about the Amish and Anabaptists in general. It is located in Lagrange, Indiana, and Aylmer, Ontario. Pathway has become the major publisher of Amish school textbooks, general-reading books, and periodicals. Also, a number of private enterprises publish everything from general reading to reprints of older literature that has been considered of great value to Amish families.[136] Some Amish read the Pennsylvania German newspaper Hiwwe wie Driwwe, and some of them even contribute dialect texts.

Dog breeding

Amish and Mennonite communities across many states have turned to dog breeding as a lucrative source of income. According to the USDA list of licensees, over 98% of Ohio's puppy mills are run by the Amish, as are 97% of Indiana's, and 63% of Pennsylvania's.[137] In Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, there are roughly 300 licensed breeders, and an estimated further 600 unlicensed breeding facilities.[138]

Reports of poor standards of care and treatment of dogs as a cash crop by members of the Amish community has led to calls for puppy mills and auctions to be closed, with one breeder being issued with a restraining order from the practice for numerous violations of the federal Animal Welfare Act. At the time the restraining order was issued, the breeder had at least 1000 dogs in their care.[139]

Similar groups

Anabaptist groups that sprang from the same late 19th century Old Order Movement as the Amish share their Pennsylvania German heritage and often still retain similar features in dress. These Old Order groups include different subgroups of Old Order Mennonites, traditional Schwarzenau Brethren and Old Order River Brethren. The Noah Hoover Old Order Mennonites are so similar in outward aspects to the Old Order Amish, including dress, beards, horse and buggy, extreme restrictions on modern technology, Pennsylvania German language, that they are often perceived as Amish and even called Amish.[140][141]

Conservative "Russian" Mennonites and Hutterites who also dress plain and speak German dialects emigrated from other European regions at different times with different German dialects, separate cultures, and related but different religious traditions.[142] Particularly, the Hutterites live communally[143] and are generally accepting of modern technology.[144]

In Ukraine there is a nameless movement of Baptists that has been compared to the Amish, due to their similar beliefs of plain living and pacifism.[145][146]

The few remaining Plain Quakers are similar in manner and lifestyle, including their attitudes toward war, but are unrelated to the Amish.[147] Early Quakers were influenced, to some degree, by the Anabaptists, and in turn influenced the Amish in colonial Pennsylvania. Almost all modern Quakers have since abandoned their traditional dress.[148]

Relations with Native Americans

The Northkill Amish Settlement, established in 1740 in Berks County, Pennsylvania, was the first identifiable Amish community in the New World. During the French and Indian War, the Hochstetler Massacre occurred: Local tribes attacked the Jacob Hochstetler homestead in the Northkill settlement on September 19, 1757. The sons of the family took their weapons but father Jacob did not allow them to shoot due to the Anabaptist doctrine of nonresistance.[8] Jacob Sr.'s wife, Anna (Lorentz) Hochstetler, a daughter (name unknown) and Jacob Jr. were killed by the Native Americans. Jacob Sr. and sons Joseph and Christian were taken captive. Jacob escaped after about eight months, but the boys were held for several years.[149] When freed, both of these sons joined the church and one of them became a minister.[8]

As early as 1809 Amish were farming side by side with Native American farmers in Pennsylvania.[150] According to Cones Kupwah Snowflower, a Shawnee genealogist, the Amish and Quakers were known to incorporate Native Americans into their families to protect them from ill-treatment, especially after the Removal Act of 1832.[151]

The Amish, as pacifists, did not engage in warfare with Native Americans, nor displace them directly, but were among the European immigrants whose arrival resulted in their displacement.[152]

In 2012, the Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society collaborated with the Native American community to construct a replica Iroquois Longhouse.[153]

See also

Notes

- Hochdeitsch is the Pennsylvania Dutch equivalent of the Standard German word Hochdeutsch; both words literally mean "High German".

- The overall suicide rate in 1980 in the US was 12.5 per 100,000.[118]

References

- "Amish Population Profile, 2023". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- Harry, Karen; Herr, Sarah A. (April 2, 2018). Life beyond the Boundaries: Constructing Identity in Edge Regions of the North American Southwest. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60732-696-0.

The Amish were one of many Anabaptist groups that grew from the Radical Reformation in sixteenth-century Europe (Hostetler 1993).

- "Anabaptists". Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

The Amish are one of many Anabaptist groups that trace their roots to the Anabaptist movement in sixteenth-century Europe at the time of the Protestant Reformation. Other groups include Mennonites, Hutterites, the Brethren in Christ, and Brethren groups that began in Schwarzenau, Germany, in 1708.

- Kraybill 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Kraybill 2001, p. 8.

- Zook, Noah; Yoder, Samuel L (1998). "Berne, Indiana, Old Order Amish Settlement". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt, (2013) The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 157–158.

- Long, Steve. "The Doctrine of Nonresistance". Pilgrim Mennonite Conference. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- Anthony L. Chute, Nathan A. Finn, Michael A. G. Haykin. The Baptist Story, Nashville, 2015, p. 12.

- C. Arnold Snyder. Anabaptist History and Theology: An Introduction. Kitchener, Ontario, 1995, p. 62.

- Smith & Krahn 1981, pp. 212–214.

- Kraybill 2000, pp. 63–64.

- Crowley, William K. (1978). "Old Order Amish Settlement: Diffusion and Growth". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 68 (2): 250–251. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1978.tb01194.x. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2562217.

- Nolt 1992, p. 159.

- Nolt 1992, pp. 157–178.

- "Our History". Fecministries.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Stephen Scott. An Introduction to Old Order and Conservative Mennonite Groups. Intercourse, Penn.: 1996, pp. 122–123.

- Kraybill, Donald B. (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites. JHU Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8018-9911-9.

- Nolt 1992.

- Nolt 1992, p. 227.

- Nolt 1992, pp. 264–266.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, Steven M. Nolt. The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013, p. 122.

- Nolt 1992, pp. 278–281.

- Nolt 1992, pp. 287–290.

- Gerlach, Horst (2013). My Kingdom Is Not of This World: 300 Years of the Amish, 1683–1983. Masthof Press & Bookstore. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-60126-387-2.

- Camden, Laura L. (2006). Mennonites in Texas: The Quiet in the Land. Texas A&M University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-60344-538-2.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt, (2013) The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 250–255.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, Steven M. Nolt. The Amish, Baltimore: 2013, p. 294.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt, The Amish Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 2013, pp. 281–282.

- "Licensed Dairy Farm Numbers Drop to Just Over 40,000". Milk Business. February 21, 2018.

- "Amish dairy farmers at risk of losing their living and way of life as their buyer drops their milk". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Kraybill, Donald B.; Johnson-Weiner, Karen M.; Nolt, Steven M. (2013). The Amish. JHU Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-4214-0914-6.

- "10 things to know about Mennonites in Canada". Canadian Mennonite. January 12, 2017. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

it is in many ways, an option of last resort and it's something we only do when we think we have a critical threat to the community's safety and we need immediate action

- Kraybill 1994, p. 3.

- "Church Discipline - Amish Studies". Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College.

- "Frequently Asked Questions - Amish Studies".

- "Amisch Teenagers Experience the World". National Geographic Television. Archived from the original on November 10, 2008.

- "Pennsylvania Amish Lifestyle". Discover Lancaster. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- Jeremiah Budin (April 23, 2023). "Amish communities are using a surprising new kind of vehicle to travel long distances: 'It's a lot quicker'". The Cool Down.

- Johnson-Weiner, Karen (2001). "The role of women in old order Amish, beachy Amish and fellowship churches". Mennonite Quarterly Review. 75: 231–257.

- Ericksen, Julia; Klein, Gary (1981). "Women's Roles and Family Production among the Old Order Amish". Rural Sociology. 46: 282–296.

- Kraybill 2001.

- "The Amish Buggy". Amish America. September 2, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- Nolt, Steven M.; Meyers, Thomas J. (2007). Plain Diversity: Amish Cultures and Identities (Young Center Books in Anabaptist and Pietist Studies). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801886058.

- Klein, H. M. J. (1946). History and customs of the Amish people. York, Pennsylvania: Maple Press Company. ASIN B004UOJ17K.

- Sherry Gore Zondervan. Simply Delicious Amish Cooking.Zondervan, 2013.

- Eicher, Lovina; Williams, Kevin (2010). The Amish Cook's Anniversary Book: 20 Years of Food, Family, and Faith. Andrews McMeel. ISBN 978-0740797651.

- Lovina Eicher. The Amish Cook at Home: Simple Pleasures of Food, Family, and Faith. 2008.

- Vincent, Bill (2012). Traditional Amish Recipes. Bloomington, Indiana.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gebra Cuyun Carter. Food Intake, Dietary Practices...Among the Amish 2008.

- Chrzan, Janet; Brett, John, eds. (2017). Food Culture: Anthropology, Linguistics and Food Studies. Berghahn Books. p. 224.

- Chrzan, Janet; Brett, John, eds. (2017). Research Methods for Anthropological Studies of Food and Nutrition: Volumes I–III, Volumes 1–3. Berghahn Books. p. 221.

- Kraybill, Donald B., Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt (eds.). The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013, p. 139.

- Subak, Susan (2018). The Five-Ton Life. University of Nebraska Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0803296886.

- "Amish Technology Use in Different Groups".

- "The Amish Community". LLCER Anglais | Site d'aide à la phonologie anglaise, grammaire, linguistique et civilisations anglophones (in Canadian French). Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Chad Thompson: The Languages of the Amish of Allen County, Indiana: Multilingualism and Convergence, in Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 69–91

- Hughes Oliphant Old: The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Volume 6: The Modern Age. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, p. 606.

- Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, p. 2

- Hostetler, John A. (1993), Amish Society, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, p. 241

- Irwin Richman: The Pennsylvania Dutch Country. Arcadia Publishing, 2004, p. 16.

- W. Haubrichs, "Theodiscus, Deutsch und Germanisch – drei Ethnonyme, drei Forschungsbegriffe. Zur Frage der Instrumentalisierung und Wertbesetzung deutscher Sprach- und Volksbezeichnungen." In: H. Beck et al., Zur Geschichte der Gleichung "germanisch-deutsch" (2004), 199–228

- Mark L. Louden: Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language. JHU Press, 2006, pp. 3–4 ISBN 1421418282

- Hurst, Charles E.; McConnell, David L. (2010). An Amish Paradox: Diversity and Change in the World's Largest Amish Community. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0801893988.

- Hurst, Charles E.; McConnell, David L. (2010). An Amish Paradox: Diversity and Change in the World's Largest Amish Community. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0801893988.

- Hugh F. Gingerich and Rachel W. Kreider. Revised Amish and Amish Mennonite Genealogies. Morgantown, Penn.: 2007. This comprehensive volume gives names, dates, and places of births and deaths, and relationships of most of the known people of this unique sect from the early 1700s until about 1860 or so. The authors also include a five-page "History of the First Amish Communities in America".

- "Genetic Disorders Hit Amish Hard". CBS News. June 8, 2005. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Hammond, Phillip E. (2000). The Dynamics of Religious Organizations: The Extravasation of the Sacred and Other Essays. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0198297628.

1. Religion is the major foundation of ethnicity, examples include the Amish, Hutterites, Jews, and Mormons. Ethnicity in this pattern, so to speak, equals religion, and if the religious identity is denied, so is the ethnic identity. [Footnote: In actuality, of course, there can be exceptions, as the labels "jack Mormon," "banned Amish," or "cultural Jew" suggest.] Let us call this pattern "ethnic fusion."

2. Religion may be one of several foundations of ethnicity, the others commonly being language and territorial origin; examples are the Greek or Russian Orthodox and the Dutch Reformed. Ethnicity in this pattern extends beyond religion in the sense that ethnic identification can be claimed without claiming the religious identification, but the reverse is rare. Let us call this pattern "ethnic religion."

3. An ethnic group may be linked to a religious tradition, but other ethnic groups will be linked to it, too. Examples include Irish, Italian, and Polish Catholics; Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish Lutherans. Religion in this pattern extends beyond ethnicity, reversing the previous pattern, and religious identification can be claimed without claiming the ethnic identification. Let us call this pattern "religious ethnicity" - Nolt 1992, p. 104.

- Gingerich, Orland (1990). "Western Ontario Mennonite Conference". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- "Amish Population Trends 1992–2013". Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "Amish Population Change Summary 1992–2008" (PDF). Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- "Amish Population Change, 2010–2015 (Alphabetical Order)" (PDF). Groups.etown.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Amish Population Profile, 2020". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. August 18, 2019. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- "The Amish Population in 2021". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- "Population Trends 1992–2008". Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Kraybill 2000.

- Ericksen, Julia A.; Ericksen, Eugene P.; Hostetler, John A.; Huntington, Gertrude E. (July 1979). "Fertility Patterns and Trends among the Old Order Amish". Population Studies. 33 (2): 255–276. doi:10.2307/2173531. ISSN 0032-4728. JSTOR 2173531. OCLC 39648293. PMID 11630609.

- "Eric Kaufmann on Immigration, Identity, and the Limits of Individualism (Ep. 70)". July 3, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- Manns, Molly. "Indiana's Amish Population". InContext. Indiana Business Research Center. Archived from the original on December 28, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- "Amish Population 2022: Amish Call New Mexico Home". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. July 29, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- Hurst, Charles E. (2010). An Amish paradox : diversity & change in the world's largest Amish community. McConnell, David L. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801893995. OCLC 647908343.

- "Amish Population by State". Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- "Iowa Amish". amishamerica.com. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- "Wisconsin Amish: Cashton" Archived April 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine at amishamerica.com.

- Amish Population in the United States and Canada by State and County, September 18, 2021 by Edsel Burdge, Jr., Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College.

- "Amish Population Change 1992–2013 (Alphabetical Order)" (PDF). Population Trends 1992–2013. 21-Year Highlights. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- 2010 U.S. Religion Census Archived August 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, official website.

- "Amish Population Change, 2000-2021" (PDF). Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. August 12, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- "Amish scout new community in P.E.I." Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Amish Moving To Fourth Canadian Province Archived October 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at amishamerica.com.

- Anderson, Cory; Anderson, Jennifer (2016). "The Amish Settlement in Honduras, 1968–1978". Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies. 4 (1): 1–50. doi:10.18061/1811/78020.

- "2016 Amish Population: Two New Settlements In South America". Amishamerica.com. June 27, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Amish Population Profile, 2018 Archived February 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine at Amish Studies – The Young Center.

- "Ixheim (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany)". Gameo.org. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Anderson, Cory (March 1, 2016). "Religious Seekers' Attraction to the Plain Mennonites and Amish". Review of Religious Research. 58 (1): 125–147. doi:10.1007/s13644-015-0222-5. ISSN 2211-4866. S2CID 142046764. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, Steven M. Nolt. The Amish. Baltimore: 2013, p. 159.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, Steven M. Nolt. The Amish. Baltimore: 2013, pp. 160f.

- Waldrep, G. C. (2008). "The New Order Amish And Para-Amish Groups: Spiritual Renewal Within Tradition". Mennonite Quarterly Review. 3: 420.

- Hoover, Peter. "Radical Anabaptists Today – Part 4". Scrollpublishing.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Waldrep, G. C. (2008). "The New Order Amish And Para-Amish Groups: Spiritual Renewal Within Tradition". Mennonite Quarterly Review. 3: 416.

- Huber, Tim (September 30, 2019). "Far-flung outposts translate Plain life". Anabaptist World. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". BeachyAM. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- McKusick, Victor A (2000). "Ellis-van Creveld syndrome and the Amish". Nature Genetics. 24 (3): 203–204. doi:10.1038/73389. PMID 10700162. S2CID 1418080.

- Harlalka, GV (2013). "Mutation of HERC2 causes developmental delay with Angelman-like features". Journal of Medical Genetics. 50 (2): 65–73. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101367. PMID 23243086. S2CID 206997462. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Morton, D. Holmes; Morton, Caroline S.; Strauss, Kevin A.; Robinson, Donna L.; Puffenberger, Erik G; Hendrickson, Christine; Kelley, Richard I. (June 27, 2003). "Pediatric medicine and the genetic disorders of the Amish and Mennonite people of Pennsylvania". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 121C (1): 5–17. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.20002. PMID 12888982. S2CID 25532297. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

Regional hospitals and midwives routinely send whole-blood filter-paper neonatal screens for tandem mass spectrometry and other modern analytical methods to detect 14 of the metabolic disorders found in these populations...

- Hostetler 1993, p. 330.

- Hostetler 1993, p. 328.

- Nolt, Steven M. (2016). The Amish: A Concise Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1421419565.

- Crowley, William K. (1978). "Old Order Amish Settlement: Diffusion and Growth". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 68 (2): 251. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1978.tb01194.x. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2562217.

- Landing, James E. (July 1969). "Geographic Models of Older Order Amish Settlements". The Professional Geographer. 21 (4): 238. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1969.00238.x. ISSN 0033-0124.

- Francomano, Clair A.; McKusick, Victor A.; Biesecker, Leslie G. (August 15, 2003). "Medical genetic studies in the Amish: Historical perspective". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 121C (1): 1–4. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.20001. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 12888981. S2CID 7688595.

- Ruder, Katherine 'Kate' (July 23, 2004). "Genomics in Amish Country". Genome News Network. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Showalter, Anita (2000). "Birthing among the Amish". International Journal of Childbirth Education. 15: 10.

- "Amish Have Lower Rates of Cancer, Ohio State Study Shows". Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Medical Center. January 1, 2010. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- "DDC Clinic for Special Needs Children". October 7, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- Kraybill 2001, p. 105.

- Kraybill (Autumn 1986), et al, "Suicide Patterns in a Religious Subculture: The Old Order Amish", International Journal of Moral and Social Studies, vol. 1

- Rubinkam, Michael (October 5, 2006). "Amish Reluctantly Accept Donations". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 27, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- "Amish Studies – Beliefs". Young Center for Anabaptist & Pietist Studies, Elizabethtown College. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- Millman, Joel (February 21, 2006). "How the Amish Drive Down Medical Costs". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- Robinson, Ryan (February 7, 2007). "Amish facing passport dilemma". LancasterOnline. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- Donald B. Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt, (2013) The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 157–158.

- Andrews, Margaret M.; Boyle, Joyceen S. (2002). Transcultural concepts in nursing care. pp. 178–180. doi:10.1177/10459602013003002. ISBN 978-0781736800. PMID 12113145. S2CID 201377433. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2008.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Iseman, David (May 18, 1988). "Trumbull probes attack on woman, Amish buggy". The Vindicator. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "Stone Amish". Painesville Telegraph. September 12, 1949. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "State Police Arrest 25 Boys in Rural Areas". The Vindicator. October 25, 1958. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- Wisconsin v. Yoder, 182 N.W.2d 539 (Wis. 1971).

- Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 32 L.Ed.2d 15, 92 S.Ct. 1526 (1972).

- "Rumble strips removed after the Amish say they're dangerous". WWMT television news. August 20, 2009. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

Dobberteen is one of a growing number of people in St. Joseph County who believes that the Amish shouldn't have a say in what happens with a state road. 'Some people are saying, "Well jeeze, you know the Amish people don't pay taxes for that, why are we filling them in" what do you think about that? We pay our taxes,' said Dobberteen. Roads are paid for largely with gas tax and vehicle registration fees, which the Amish have no reason to pay.

- Kraybill, Donald. "Top Ten FAQ (about the Amish)". PBS/The American Experience. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- Kelley, Daniel (October 6, 2013). "As U.S. struggles with health reform, the Amish go their own way". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "U.S. Code collection". Cornell Law School. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- "Application for Exemption From Social Security and Medicare Taxes and Waiver of Benefits" (PDF). Internal Revenue Service. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- "U.S. v. Lee, 102 S. Ct. 1051 (1982)". August 20, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

On appeal, the Supreme Court noted that the exemption provided by 26 U.S.C. 1402(g) is available only to self-employed individuals and does not apply to employers or employees. As to the constitutional claim, the court held that since accommodating the Amish beliefs under the circumstances would unduly interfere with the fulfillment of the overriding governmental interest in assuring mandatory and continuous participation in and contribution to the Social Security system, the limitation on religious liberty involved here was justified. Consequently, in reversing the district court, the Supreme Court held that, unless Congress provides otherwise, the tax imposed on employers to support the Social Security system must be uniformly applicable to all.

- "Pathway Publishers". Gameo.org. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "APHIS Public Search Tool". aphis-efile.force.com. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- "Puppies 'Viewed as Livestock' in Amish Community, Says Rescue Advocate". ABC News. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- Kauffman, Clark (October 1, 2021). "Citing 'shocking' actions of Iowa dog breeder, judge issues restraining order". Iowa Capital Dispatch. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- "7 News Belize". 7newsbelize.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- "Stauffer Mennonite Church". Gameo.org. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Elizabethtown College". Etown – Young Center. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- "Hutterites". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Laverdure, Paul (2006). "Hutterites". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Canadian Plains Research Center. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Romanyshyn, Yuliana (November 1, 2015). "They live like Amish, but they are not". KyivPost. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- Mash, Dave (December 7, 2021). "Living the Amish faith half way across the world…". The Bargain Hunter. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- Hamm 2003, p. 101.

- Hamm 2003, pp. 103–105.

- Nolt, Steven M. (May 2016). The Amish. JHU Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4214-1956-5.

- "WGBH American Experience. The Amish". PBS. Archived from the original on December 7, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- Cones Kupwah Snowflower in NAAH No. July 14, 1996 "Let's Get Physical"

- "Gathering at the Hearth: Stories Mennonites Tell". Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- "Attempting to Repair the Past: An American Indian Longhouse Exhibit Coming to Amish Country". Indiancountrymedianetwork.com. April 29, 2012. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

Bibliography

- Hamm, Thomas D. (2003). The Quakers in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50893-3. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- Hostetler, John (1993), Amish Society (4th ed.), Baltimore, Maryland; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-4442-3.

- Kraybill, Donald B (1994), Olshan, Marc A (ed.), The Amish Struggle with Modernity, Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, p. 304.

- Kraybill, Donald B, The Anabaptist Escalator.

- ——— (2001) [2000], Anabaptist World USA, Herald Press, ISBN 978-0-8361-9163-9.

- ——— (2001), The Riddle of Amish Culture (revised ed.), JHU Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-6772-9.

- Nolt, Steven M. (1992), A History of the Amish, Intercourse: Good Books.

- "Swiss Amish", Amish America, Type pad, archived from the original on March 2, 2009, retrieved March 26, 2009.

Further reading

- Die Botschaft – Lancaster, PA – Newspaper for Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites; only Amish may place advertisements.

- The Diary – Gordonville, PA – Monthly newsmagazine by and for Old Order Amish.

- Beachy, Leroy (2011). Unser Leit ... The Story of the Amish. Millersburg, OH: Goodly Heritage Books. ISBN 0-9832397-0-3

- DeWalt, Mark W. (2006). Amish Education in the United States and Canada. Rowman and Littlefield Education.

- Garret, Ottie A and Ruth Irene Garret (1998). True Stories of the X-Amish: Banned, Excommunicated and Shunned, Horse Cave, KY: Neu Leben.

- Garret, Ruth Irene (1998). Crossing Over: One Woman's Escape from Amish Life, Thomas More.

- Gehman Richard. "Plainest of Pennsylvania's Plain People Amish Folk". National Geographic, August 1965, pp. 226–53.

- Good, Merle and Phyllis (1979). 20 Most Asked Questions about the Amish and Mennonites. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

- Hostetler, John A. ed. (1989). Amish Roots: A Treasury of History, Wisdom, and Lore. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Igou, Brad (1999). The Amish in Their Own Words: Amish Writings from 25 Years of Family Life, Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

- Johnson-Weiner, Karen M. (2006). Train Up a Child: Old Order Amish and Mennonite Schools. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Johnson-Weiner, Karen M. (2017) New York Amish : Life in the Plain Communities of the Empire State (Cornell UP, 2017).

- Keim, Albert (1976). Compulsory Education and the Amish: The Right Not to be Modern. Beacon Press.

- Kraybill, Donald B., Karen M. Johnson-Weiner, and Steven M. Nolt, The Amish (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 500 pp.

- Kraybill, Donald B. "Amish." in Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2014), pp. 97–112. online Archived April 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Kraybill, Donald B. (2008). The Amish of Lancaster County. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.* Kraybill, Donald B. ed. (2003). The Amish and the State. Foreword by Martin E. Marty. 2nd ed.: Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kraybill, Donald B. (2014). Renegade Amish: Beard Cutting, Hate Crimes, and the Trial of the Bergholz Barbers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kraybill, Donald B. & Carl D. Bowman (2002). On the Backroad to Heaven: Old Order Hutterites, Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kraybill, Donald B. & Steven M. Nolt (2004). Amish Enterprise: From Plows to Profits. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kraybill, Donald B., Steven M. Nolt & David L. Weaver-Zercher (2006). Amish Grace: How Forgiveness Transcended Tragedy. New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Kraybill, Donald B., Steven M. Nolt & David L. Weaver-Zercher (2010). The Amish Way: Patient Faith in a Perilous World. New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Luthy, David (1991). Amish Settlements That Failed, 1840–1960. LaGrange, IN: Pathway Publishers.

- Mackall, Joe: Plain Secrets: An Outsider among the Amish, Boston, Mass. 2007.

- Nolt, Steven M. and Thomas J. Myers (2007). Plain Diversity: Amish Cultures and Identities. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Schachtman, Tom (2006). Rumspringa: To be or not to be Amish. New York: North Point Press.

- Schlabach, Theron F. (1988). Peace, Faith, Nation: Mennonites and Amish in Nineteenth-Century America. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

- Schmidt, Kimberly D., Diane Zimmerman Umble, & Steven D. Reschly, eds. (2002) Strangers at Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Scott, Stephen (1988). The Amish Wedding and Other Special Occasions of the Old Order Communities. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

- Smith, C Henry; Krahn, Cornelius (1981), Smith's Story of the Mennonites (revised & expanded ed.), Newton, Kansas: Faith and Life Press, pp. 249–356, ISBN 978-0-87303-069-4.

- Smith, Jeff (2016). Becoming Amish. Cedar, MI: Dance Hall Press

- Stevick, Richard A. (2007). Growing Up Amish: the Teenage Years. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Umble, Diane Zimmerman (2000). Holding the Line: the Telephone in Old Order Mennonite and Amish Life. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Umble, Diane Zimmerman & David L. Weaver-Zercher, eds. (2008). The Amish and the Media. Johns Hopkins University Press

- Weaver-Zercher, David L. (2001). The Amish in the American Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Yoder, Harvey (2007). The Happening: Nickel Mines School Tragedy. Berlin, OH: TGS International.

External links

- The Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies