Saint Stephen

Stephen (Greek: Στέφανος Stéphanos, meaning 'wreath or crown' and by extension 'reward, honor, renown, fame', often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first martyr of Christianity.[1] According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was a deacon in the early Church at Jerusalem who angered members of various synagogues by his teachings. Accused of blasphemy at his trial, he made a speech denouncing the Jewish authorities who were sitting in judgment on him[2] and was then stoned to death. Saul of Tarsus, later known as Paul, a Pharisee and Roman citizen who would later become a Christian apostle, participated in Stephen's martyrdom.[3]

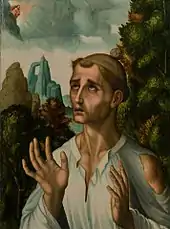

Stephen | |

|---|---|

Saint Stephen by Carlo Crivelli | |

| Deacon, Archdeacon Apostle of the Seventy Protomartyr of The Faith First Martyr | |

| Born | 5 AD |

| Died | 33–36 AD (aged 28–32) Jerusalem, Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Churches Assyrian Church of the East Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast | 25 December (Armenian Christianity) 26 December (Western) 27 December, 4 January, 2 August, 15 September (Eastern) Tobi 1 (Coptic Christianity) |

| Attributes | Red Martyr, stones, dalmatic, censer, miniature church, Gospel Book, martyr's palm. In Orthodox and Eastern Christianity he often wears an orarion |

| Patronage | Altar Servers ;Acoma Native American Pueblo; Bricklayers; casket makers; Cetona, Italy; deacons; headaches; horses; Kessel, Belgium; masons; Owensboro, Kentucky; Passau, Germany; Kigali, Rwanda; Dodoma, Tanzania; Serbia; Ligao; Republic of Srpska; Prato, Italy |

The only source for information about Stephen is the New Testament book of the Acts of the Apostles.[4] Stephen is mentioned in Acts 6 as one of the Greek-speaking Hellenistic Jews selected to administer the daily charitable distribution of food to the Greek-speaking widows.[5]

The Catholic, Anglican, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, and Lutheran churches and the Church of the East view Stephen as a saint.[6] Artistic representations often show Stephen with a crown symbolising martyrdom, three stones, martyr's palm frond, censer, and often holding a miniature church building. Stephen is often shown as a young, beardless man with a tonsure, wearing a deacon's vestments.

Background

Stephen is first mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles as one of seven deacons appointed by the Apostles to distribute food and charitable aid to poorer members of the community in the early church. According to Orthodox belief, he was the eldest and is therefore called "archdeacon".[7] As another deacon, Nicholas of Antioch, is specifically stated to have been a convert to Judaism, it may be assumed that Stephen was born Jewish, but nothing more is known about his previous life.[4] The reason for the appointment of the deacons is stated to have been dissatisfaction among Hellenistic (that is, Greek-influenced and Greek-speaking) Jews that their widows were being slighted in preference to Hebraic ones in the daily distribution of food. Since the name "Stephanos" is Greek, it has been assumed that he was one of these Hellenistic Jews. Stephen is stated to have been full of faith and the Holy Spirit and to have performed miracles among the people.[8]

It seems to have been among synagogues of Hellenistic Jews that he performed his teachings and "signs and wonders" since it is said that he aroused the opposition of the "Synagogue of the Freedmen", and "of the Cyrenians, and of the Alexandrians, and of them that were of Cilicia and Asia".[9] Members of these synagogues had challenged Stephen's teachings, but Stephen had bested them in debate. Furious at this humiliation, they suborned false testimony that Stephen had preached blasphemy against Moses and God. They dragged him to appear before the Sanhedrin, the supreme legal court of Jewish elders, accusing him of preaching against the Temple and the Mosaic Law.[10] Stephen is said to have been unperturbed, his face looking like "that of an angel".[4]

Speech to Sanhedrin

In a long speech to the Sanhedrin comprising almost the whole of Acts chapter 7, Stephen presents his view of the history of Israel. The God of glory, he says, appeared to Abraham in Mesopotamia, thus establishing at the beginning of the speech one of its major themes, that God does not dwell only in one particular building (meaning the Temple).[11] Stephen recounts the stories of the patriarchs in some depth, and goes into even more detail in the case of Moses. God appeared to Moses in the burning bush,[12] and inspired Moses to lead his people out of Egypt. Nevertheless, the Israelites turned to other gods.[13] This establishes the second main theme of Stephen's speech, Israel's disobedience to God.[11] Stephen faced two accusations: that he had declared that Jesus would destroy the Temple in Jerusalem and that he had changed the customs of Moses. Pope Benedict XVI stated in 2012 that St. Stephen appealed to the Jewish scriptures to prove how the laws of Moses were not subverted by Jesus but, instead, were being fulfilled.[14] Stephen denounces his listeners[11] as "stiff-necked" people who, just as their ancestors had done, resist the Holy Spirit. "Was there ever a prophet your ancestors did not persecute? They even killed those who predicted the coming of the Righteous One. And now you have betrayed and murdered him."[15]

The stoning of Stephen

Thus castigated, the account is that the crowd could contain their anger no longer.[16] However, Stephen looked up and cried, "Look! I see heaven open and the Son of Man standing on the right hand of God!" He said that the recently resurrected Jesus was standing by the side of God.[17][18] The people from the crowd, who threw the first stones,[19][17] laid their coats down so as to be able to do this, at the feet of a "young man named Saul" (later identified as Paul the Apostle). Stephen prayed that the Lord would receive his spirit and his killers be forgiven, sank to his knees, and "fell asleep".[20] Saul "approved of their killing him."[21] In the aftermath of Stephen's death, the remaining disciples except for the apostles fled to distant lands, many to Antioch.[22][23]

Location of the martyrdom

The exact site of Stephen's stoning is not mentioned in Acts; instead there are two different traditions. One, claimed by noted French archaeologists Louis-Hugues Vincent (1872–1960) and Félix-Marie Abel (1878–1953) to be ancient, places the event at Jerusalem's northern gate, while another one, dated by Vincent and Abel to the Middle Ages and no earlier than the 12th century, locates it at the eastern gate.[24]

Views of Stephen's speech

Of the numerous speeches in Acts of the Apostles, Stephen's speech to the Sanhedrin is the longest.[25] To the objection that it seems unlikely that such a long speech could be reproduced in the text of Acts exactly as it was delivered, some Biblical scholars have replied that Stephen's speech shows a distinctive personality behind it.[11]

There are at least five places where Stephen's re-telling of the stories of Israelite history diverges from the scriptures where these stories originated; for instance, Stephen says that Jacob's tomb was in Shechem,[26] but Genesis 50:13[27] says Jacob's body was carried and buried in a cave in Machpelah at Hebron.[28][11] Some theologians argue that these may not be discrepancies, but rather a condensing of historical events for people who were already familiar with them.[29] That Jacob's body was carried to a final resting place in Shechem is not recorded in Genesis, though it does not exclude the possibility that his bones were transferred to Shechem for a final burial place, as was done with the bones of Jacob's son Joseph, as described in Joshua 24:32 Other scholars consider them as errors. Still others interpret them as deliberate choices making theological points.[25] Another possibility is that the discrepancies come from an ancient Jewish tradition which was not included in the scriptures or may have been popular among people of Jerusalem who were not scribes.[30]

Numerous parallels between the accounts of Stephen in Acts and the Jesus of the Gospels – they both perform miracles, they are both tried by the Sanhedrin, they both pray for forgiveness for their killers, for instance – have led to suspicions that the author of Acts has emphasised – in order to show the recipient that people become holy when they follow the example of Christ – or invented some (or all) of these.[17]

The criticism of traditional Jewish belief and practice in Stephen's speech is very strong – when he says God does not live in a dwelling "made by human hands", referring to the Temple, he is using an expression often employed by Biblical texts to describe idols.[11]

Some people have laid the charge of anti-Judaism against the speech, for instance the priest and scholar of comparative religion S. G. F. Brandon, who states: "The anti-Jewish polemic of this speech reflects the attitude of the author of Acts."[31]

Commentary

Friedrich Justus Knecht lists the similarities of the martyrdom of Stephen to Jesus' death on the cross:

1. Our Blessed Lord was sentenced to death on the charge of blasphemy, because He had affirmed on oath: "I am the Son of the living God, and hereafter you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of God". In the same manner Stephen was stoned on the assumption that he was a blasphemer, and because he professed his belief in the Divinity of Jesus, and said: "I see heaven open, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God". 2. Both our Blessed Lord and St. Stephen were treated as outcasts, and put to death outside the city. 3. Both, when dying, prayed for their enemies: "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do". – "Lay not this sin to their charge". 4. Both, before dying, commended their souls to God: "Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit". – "Lord Jesus, receive my soul!”[32]

Tomb and relics of Stephen

Acts 8:2[33] says "Godly men buried Stephen and mourned deeply for him," but the location where he was buried is not specified.

In 415, a priest named Lucian purportedly had a dream that revealed the location of Stephen's remains at Beit Jimal. After that, the relics of the protomartyr were taken in procession to the Church of Hagia Sion on 26 December 415, making it the date for the feast of Saint Stephen. In 439, the relics were translated to a new church north of the Damascus Gate built by the empress Aelia Eudocia in honor of Saint Stephen. This church was destroyed in the 12th century. A 20th-century French Catholic church, Saint-Étienne, was built in its place, while another, the Greek Orthodox Church of St Stephen, was built outside the eastern gate of the city,[34] which a second tradition holds to be the site of his martyrdom, rather than the northern location outside Damascus Gate (for the two traditions see here).

The Crusaders initially called the main northern gate of Jerusalem "Saint Stephen's Gate" (in Latin, Porta Sancti Stephani), highlighting its proximity to the site of martyrdom of Saint Stephen, marked by the church and monastery built by Empress Eudocia.[35] A different tradition is documented from the end of the Crusader period, after the disappearance of the Byzantine church: as Christian pilgrims were prohibited from approaching the militarily exposed northern city wall, the name "Saint Stephen's Gate" was transferred to the still accessible eastern gate, which bears this name until this day.[36]

The relics of the protomartyr were later translated to Rome by Pope Pelagius II during the construction of the basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura. They were interred alongside the relics of Saint Lawrence, whose tomb is enshrined within the church. According to the Golden Legend, the relics of Lawrence moved miraculously to one side to make room for those of Stephen.[37]

The Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Empire includes a relic known as St. Stephen's Purse which is an elaborate gold and jewel-encrusted box believed to contain soil soaked with the blood of St. Stephen. The reliquary is likely a 9th-century creation.

In his book The City of God, Augustine of Hippo describes the many miracles that occurred when part of the relics of Saint Stephen were brought to Africa.[38]

Part of the right arm of Saint Stephen is enshrined at Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in Russia.[39][40][41][42]

Saint Stephen's Day

Public holidays

In Western Christianity, 26 December is called "Saint Stephen's Day", the "Feast of Stephen" mentioned in the English Christmas carol "Good King Wenceslas". It is a public holiday in many nations that are of historic Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran traditions, including Austria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovakia, Poland, Italy, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Catalonia and the Balearic Isles. In Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom, the day is celebrated as "Boxing Day".

Western Christianity

In the current norms for the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, the feast is celebrated at the Eucharist, but, for the Liturgy of the Hours, is restricted to the Hours during the day, with Evening Prayer being reserved to the celebration of the Octave of Christmas. Historically, the "Invention of the Relics of Saint Stephen" (i.e., their reputed discovery) was commemorated on 3 August.[43] The feasts of both 26 December and 3 August have been used in dating clauses in historical documents produced in England.[44] Stephen is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 26 December.[45]

Eastern Christianity

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite, and in Oriental Orthodox Churches (e.g., Coptic, Syrian, Malankara) Saint Stephen's feast day is celebrated on 27 December, due to the celebration of the Synaxis of the Theotokos on 26 December. This also has the effect of pushing the Feast of the Holy Innocents to 29 December. This day is also called the "Third Day of the Nativity" because it is the third day of the Christmas season.

Some Orthodox churches, particularly in the west, follow a modified Julian calendar that places date names identically with the standard Gregorian calendar of widespread civil usage. In those churches, then, the date the feast is observed is generally known as 27 December. However, other Orthodox churches, including the Oriental Orthodox, continue to use the original Julian calendar. Throughout the 21st century, 27 December Julian will continue to fall on 9 January in the Gregorian calendar, and that is the date on which they observe the feast.

Saint Stephen is also commemorated on 4 January (Synaxis of the Seventy Apostles) in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Uncovering of his relics (relics of the saints: Nicodemus, Gamaliel and Abibas son of Gamaliel were also found in Saint Stephen's tomb) took place in 415, Gamaliel appeared to presbyter Lucian and he told him to go to Jerusalem and inform Bishop John about relics of Saint Stephen.[46] Bishop John II with bishops Eusthia (from Sebastia) and Eleutherius (from Jericho) came to the tomb in Beit Jimal and translated relics to Jerusalem, this event is commemorated on 15 September.[47][48][49]

In 428 (when Saint Theodosius II the Younger Roman Emperor) relics of saint: Stephen, Nicodemus, Gamaliel and Abibas were translated from Jerusalem to Constantinople and relics have been placed in Saint Lawrence church, and after preparations were made relics were moved to specially prepared Saint Stephen church in Constantinople, this event took place on 2 August.[50][48][49]

Armenian Liturgy

In the Armenian Apostolic and Armenian Catholic Churches, Saint Stephen's Day falls on 25 December – the day on which the feast of the Nativity of Jesus (Christmas) falls in all other churches. This is because the Armenian churches maintain the decree of Constantine, which stipulated that the Nativity and Theophany of Jesus were to be celebrated on 6 January. In dioceses of the Armenian Church which use the Julian Calendar, Saint Stephen's Day falls on 7 January and Nativity/Theophany on 19 January (for the remainder of the 21st century Julian).

In the eucharistic celebration on this feast day, it is traditional for all deacons serving at the altar to wear a liturgical crown (Armenian: խոյր khooyr), which is one of the vestments worn only by priests on all other days of the year, the crown being in this instance a symbol of martyrdom.

Commemorative places

- See also: St. Stephen's Cathedral, St. Stephen's Church

Many churches and other places commemorate Stephen. Among the most notable are the two sites in Jerusalem held by different traditions to be the place of his martyrdom, the Salesian monastery of Beit Jimal in Israel held to be the place where his remains were miraculously found, and the church of San Lorenzo fuori le Mura in Rome, where the saint's remains are said to be buried.

Important churches and sites dedicated to Saint Stephen are:

Armenian churches

- Saint Stephen Church of Lmbat of the 7th century, near the town of Artik, Armenia

- Saint Stephen Armenian Monastery of the 9th century, near the city of Jolfa, northwestern Iran

- St. Stepanos Armenian Church of Izmir, Turkey, built in 1863 and destroyed in September 1922 during the Catastrophe of Smyrna

Australia

- St Stephen's Cathedral, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia – is the primary Catholic place of worship in the archdiocese of Brisbane.

Austria

- Stephansdom, Vienna, Austria – the Cathedral of St. Stephen, founded 1147 and seat of the Archbishop of Vienna. Symbol of the city of Vienna and of Austria, has the tallest spire in Austria and is the "centerpiece of Vienna"[51]

France

- Saint Étienne, France, and numerous other places named Saint Étienne in the French-speaking world (Étienne is the French form of Stephen)

India

- St. Stephen's School (ICSE/ISC), Sonarpur, Kolkata, Under Church of North India in India Principal, Hebron Larruna Peters

- St. Stephen's Church, Kombuthurai, built by Francis Xavier in India in 1542

- St. Stephen's knanaya Catholic Forane Church, Uzhavoor, Kottayam, built 1631

- St. Stephen's Orthodox Cathedral, Kudassanad, Pandalam, Kerala the first Orthodox Cathedral of Saint Stephen in India

- St. Stephen's College, Delhi

- St. Stephen's Church, Delhi and St. Stephen's Hospital, Delhi

- St. Stephen's School, Chandigarh founded in 1986

- St. Stephen's Church, Thope, is one of the parishes of the first diocese of India, Kollam. It is 216 years old and the patron of this parish is St. Stephen, the first Martyr of the Church and it is situated beside Kollam Beach.

- St Stephen Church in Santo Estêvão, Goa, India

- St. Stephan's Orthodox Syrian Church, Kattanam ( Kattanam Valiyapalli)

Ireland

- St Stephen's Green, Dublin. The largest of Dublin's Georgian squares and itself named after a former leper hospital near the site[52]

- Church of St. Stephen, Tyrrellspass, located in Tyrrellspass, County Westmeath

Italy

- Rome – Santo Stefano Rotondo, a church built under the commission of Constantine I on the ruins of the Caelian Hill of Rome. Built in the 5th century, it is the first church in Rome to have a circular floor plan, instead of the traditional Greek or Latin cross designs.[53]

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, where Saint Stephen is said to be interred together with Saint Lawrence in the crypt, under the high altar.

- Vatican City – Santo Stefano degli Abissini, Coptic Christian church in Vatican City, that is also the National Church of Ethiopia in Rome.

- Rome – Basilica Papale di San Paolo fuori le Mura, a side chapel to St. Stephen is about a stone's throw from the tomb of St. Paul.

- Milan – Basilica di Santo Stefano Maggiore, a baroque church built in the fifth century and originally dedicated to both Saint Stephen and Saint Zecheriah.

Holy Land

- St. Stephen's Basilica, Jerusalem, in French Saint-Étienne, at the traditional place of St Stephen's martyrdom; modern church over ruins of Byzantine 5th-century predecessor

- St. Stephan's Gate, the Christian name of one of the city gates of the Old City of Jerusalem, also known as the "Lions' Gate". A post-Byzantine tradition holds that Stephen's stoning occurred there, while an older tradition connects the martyrdom to the Damascus Gate, where a church and large monastic complex dedicated to Saint Stephen was built in the 5th century (see above). A modern Greek Orthodox Church of Saint Stephen stands a short distance from Lions' Gate.

United Kingdom

- St Stephen's Chapel in the Palace of Westminster, London, was originally built in the reign of Henry III of England; it became the first site of the debating chamber of the British House of Commons. The tower that houses Big Ben, that was properly called The Clock Tower, was referred to as St Stephen's Tower by Victorian journalists.[54] The Clock Tower was renamed Elizabeth Tower to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II in 2013. St Stephen's Tower is the smaller tower in the middle of the building.

- St Stephen's House, Oxford – a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford and Anglican theological college

- St Stephen's Church, Bristol – a city church built outside the walls c. 1250, rebuilt c. 1430–1490

- St Stephen's, Sneinton, Nottingham – has strong links to William Booth and The Salvation Army. The parents of D.H. Lawrence married in the church on 27 December 1875.

- St Stephen's Walbrook, City of London – first recorded in C11 and rebuilt to Wren's design after the Great Fire

United States

- St. Stephen the martyr church, Renton, Washington[55]

- St. Stephen Parish in Portland, Oregon

- St. Stephen Church in Cleveland, Ohio

- St. Stephen Protomartyr Catholic Church and Parish in St. Louis, Missouri[56]

- St. Stephen's Church in Boston, Massachusetts

- St. Stephen Catholic Church in Cincinnati, Ohio

- St. Stephen's Church in Providence, RI[57]

- St. Stephen the Martyr Church, Omaha, Nebraska[58]

Other associations

- In the Catholic Church, the Guild of St. Stephen is an international association of altar servers whose aim is to promote "highest standards of serving at the Church's liturgy".[59]

- Saint Stephen is one of the sculptures on the side of the Orsanmichele in Florence. Saint Stephen is the patron saint of the wool guild.

- In the 14th −16th century, the bishopric of Halberstadt issued one-sided stamped silver coins. The obverse showed the face of St. Stephen in chief over two large rocks in base and a martyr's palm frond (palmwedel) on the left side. The halo around St. Stephen's head and the two rocks being mistaken for hands made it look like he was lying in state inside of a coffin (sarg). Thus they were nicknamed sargpfennig ("coffin pennies").

- Saint Stephen is featured as the eponymous subject of a song by the Grateful Dead.

See also

- Saint Stephen, patron saint archive

- Guilds of Florence

- Stephen Ministry

References

- "St. Stephen the Deacon" Archived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, St. Stephen Diaconal Community Association, Roman Catholic Diocese of Rochester.

- Acts 7:51–53

- Acts 22:20

- Souvay, Charles. "Saint Stephen". Catholic Encyclopedia,1912. New Advent. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Mal Couch, A Bible Handbook to the Acts of the Apostles, 2003, p. 246. "Stephen is distinguished as "a man full of faith and of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 6:5). Stephen and the other men were Hellenistic Jews whose native language was Greek. He had lived with Gentiles in other parts of the Roman Empire."

- "Article XXI (IX) Of the Invocation of the Saints".

- "Protomartyr and Archdeacon Stephen".

- Acts 6:5, 8

- Acts 6:9

- Acts 6:9–14

- David J. Williams (1989), Acts (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series), Baker Books, Chapter 16, ISBN 978-0-8010-4805-0.

- Acts 7:30–32

- Acts 7:39–43

- Kerr, David. "St. Stephen's death shows importance of Scripture, Pope says", Catholic News Agency, 2 May 2012.

- Acts 7:51–53

- "of Saints", John J. Crawley & Co., Inc". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- David J. Williams, Acts (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series), Baker Books 1989, chapter 17, ISBN 978-0-8010-4805-0

- Acts 7:54

- Deuteronomy 13:9 and Deuteronomy 17:7

- Acts 7:58–60

- Acts 8:1

- Acts 11:19–20

- Unger, Merrill F. (2006) [1957]. Harrison, R. K. (ed.). The New Unger's Bible Dictionary. Chicago: Moody Publishers. Antioch Ariana Grande Yuh. ISBN 978-0-8024-9066-7.

- Hannah M. Cotton; Leah Di Segni; Werner Eck; et al., eds. (2012). Jerusalem, Part 2: 705–1120. Corpus Inscriptionum Iudeae/Palaestinae. Vol. 1. De Gruyter. p. 275. ISBN 978-3-11-025188-3. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

.... St. Stephen's Gate (Lions' gate; Bab Sitti Mariam). The gate owes its name to a tradition according to which Stephen the Deacon, the first martyr, was stoned on this spot. At the beginning of the 20 c. the Greek Orthodox Patriarchy built a church dedicated to the Protomartyr in their property in front of the gate, in an endeavour to pinpoint the tradition of the site, which was falling into oblivion following the construction of the Dominican church and monastery on the site of the Eudocian church of St. Stephen north of Damascus Gate. The Greek builders went so far as to maintain that, in digging the foundations of the new church, they had found a broken lintel with an engraved invocation to Saint Stephen, but their claim, accepted by Macalister and Vailhé, was promptly disproved by Vincent, who was able to show that the lintel came in fact from Beersheba. Vincent and Abel maintained that the tradition about Stephen's stoning at the eastern gate of Jerusalem was not earlier than the 12 c., while the tradition pointing to the northern gate was ancient. .... J. Milik .... suggested that all the tombstones discovered in this area belonged to the cemetery of the Probatica.

- Rex A. Koivisto (1987). "Stephen's Speech: A Theology of Errors?" (PDF). Grace Theological College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Acts 7:16

- Genesis 50:13

- Acts 8:1

- Balge, Richard (2016). The People's Bible: Acts. Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8100-1190-8.

- Marian Wolniewicz as the translator of the Book of Acts from: The Millennium Holy Bible; Warsaw, 1980

- Brandon, S. G. F. (1967). Jesus and the Zealots: A Study of the Political Factor in Primitive Christianity. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-684-31010-7.

- Friedrich Justus Knecht (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- Acts 8:2

- "St Stephen Church". Ministry of Tourism, Government of Israel. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Adrian J. Boas (2001). Jerusalem in the time of the crusades: society, landscape, and art in the Holy City under Frankish rule (Illustrated, reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-415-23000-1.

- Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

The local guides simply moved to the Kidron valley certain holy places, notably the church of Saint Stephen, which in reality were north of the city, and business went on as before.

- "Golden Legend – Invention of Saint Stephen, Protomartyr". CatholicSaints.Info. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Augustine, City of God, Book XXII, Chapter 8, accessed 3 July 2021

- Sanidopoulos, John. "Translation of the Relics of Saint Stephen the Protomartyr". Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "Перст первомученика и архидиакона Стефана – среди особо почитаемых святынь Киево-Печерской Лавры". Православная Жизнь (in Russian). Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "В Троице-Сергиевой Лавре молитвенно почтили святого первомученика и архидиакона Стефана".

- "Обретение мощей первомученика архидиакона Стефана (415)".

- Oxford Dictionary of Saints, ed. David Hugh Farmer, corr. ed. (Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1979), p. 361. ISBN 0198691203

- Handbook of dates for students of British history, ed. C. R. Cheney. New, rev. ed. (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 59, 85. ISBN 0521770955

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- "Finding of the relics of Saint Gamaliel". oca.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "Uncovering of the relics of the Holy Protomartyr and Archdeacon Stephen". oca.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "THE TRANSFER FROM JERUSALEM TO CONSTANTINOPLE OF THE RELICS OF THE HOLY FIRSTMARTYR STEPHEN". holytrinityorthodox.com. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "Orthodox Calendar. HOLY TRINITY RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH, a parish of the Patriarchate of Moscow". holytrinityorthodox.com. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "Translation of the relics of the Protomartyr and Archdeacon Stephen from Jerusalem to Constantinople". oca.org. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "St. Stephen's Cathedral (Stephansdom)". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "St. Stephen's Green" (PDF). Phoenix Park. The Office of Public Works. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Santo Stefano Rotondo – Rome, Italy".

- "Frequently asked questions: Big Ben and Elizabeth Tower". UK Parliament.

- St. Stephen's Church, Renton, WA

- St. Stephen Protomartyr Catholic Church, St. Louis, Missouri

- St. Stephen's Church, Providence, RI

- St. Stephen the Martyr Catholic Church, Omaha, NE

- Guild of St. Stephen, accessed 21 March 2018