Artaphernes

Artaphernes (Greek: Ἀρταφέρνης, Old Persian: Artafarna,[1] from Median Rtafarnah), flourished circa 513–492 BC, was a brother of the Achaemenid king of Persia, Darius I, satrap of Lydia from the capital of Sardis, and a Persian general. In his position he had numerous contacts with the Greeks, and played an important role in suppressing the Ionian Revolt.[2]

Artaphernes | |

|---|---|

Achaemenid nobleman, 520-480 BC. | |

| Native name | Artafarna |

| Allegiance | Achaemenid Empire |

| Years of service | 513-492 BC |

| Rank | Satrap of Lydia |

| Battles/wars | Ionian revolt |

| Children | Artaphernes II |

| Relations | Darius the Great (brother) |

Biography

First contacts with Athens (507 BC)

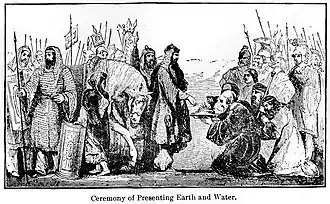

In 507 BC, Artaphernes, as brother of Darius I and Satrap of Asia Minor in his capital Sardis, received an embassy from Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, which was looking for Persian assistance in order to resist the threats from Sparta.[3][4] Artaphernes asked the Athenians for "Earth and Water", a symbol of submission, if they wanted help from the Achaemenid king.[4] The Athenians ambassadors apparently accepted to comply, and to give "Earth and Water".[3] Artaphernes also advised the Athenians that they should receive back the Athenian tyrant Hippias. The Persians threatened to attack Athens if they did not accept Hippias.

After that, the Athenians sent to bring back Cleisthenes and the seven hundred households banished by Cleomenes; then they despatched envoys to Sardis, desiring to make an alliance with the Persians; for they knew that they had provoked the Lacedaemonians and Cleomenes to war. When the envoys came to Sardis and spoke as they had been bidden, Artaphrenes son of Hystaspes, viceroy of Sardis, asked them, "What men are you, and where dwell you, who desire alliance with the Persians?" Being informed by the envoys, he gave them an answer whereof the substance was, that if the Athenians gave king Darius earth and water, then he would make alliance with them; but if not, his command was that they should begone. The envoys consulted together and consented to give what was asked, in their desire to make the alliance. So they returned to their own country, and were then greatly blamed for what they had done.

— Herodotus 5.73.[5]

Nevertheless, the Athenians preferred to remain democratic despite the danger from Persia, and the ambassadors were disavowed and censured upon they return to Athens.[3] There is a possibility though that the Achaemenid ruler now saw the Athenians as subjects who had solemnly promised submission through the gift of "Earth and Water", and that subsequent actions by the Athenians were perceived as a break of oath, and a rebellion to the central authority of the Achaemenid ruler.[3]

Siege of Naxos (499 BC)

The Siege of Naxos (499 BC), a failed attempt by the Milesian tyrant Aristagoras, to conquer the island of Naxos in the name of the Persian Empire, was supported by Artaphernes who assisted in the assembly of a force of 200 triremes under the command of Megabates. This was the opening act of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would ultimately last for 50 years.

Ionian revolt (499-494 BC)

Soon after this, the Ionian Revolt began, at the instigation of Aristagoras who thus tried to escape punishment for his failure at the Siege of Naxos.[3] Subsequently, Artaphernes played an important role in suppressing the Ionian Revolt.[2]

Athens and Eretria responded to the Ionian Greeks’ plea for help against Persia and sent troops. Athenian and Eretrian ships transported the Athenian troops to the Ionian city of Ephesus. There they were joined by a force of Ionians and they marched upon Sardis, leading to the Siege of Sardis (498 BC).

Artaphernes, who had sent most of his troops to besiege Miletus, was taken by surprise. However, Artaphernes was able to retreat to the citadel and hold it. Although the Greeks were unable to take the citadel, they pillaged the town and set fires that burnt Sardis to the ground. Returning to the coast, the Greek forces were met by the Persians, led by Artaphernes, who overpowered the Greeks.

Having successfully captured several of the revolting Greek city-states, the Persians under Artaphernes laid siege to Miletus. The decisive Battle of Lade was fought in 494 BC close to the island of Lade, near Miletus' port. Although out-numbered, the Greek fleet appeared to be winning the battle until the ships from Samos and Lesbos retreated. The sudden defection turned the tide of battle, and the remaining Greek fleet was completely destroyed. Miletus surrendered shortly thereafter and the Ionian Revolt effectively came to an end.

After the revolt was put down, Artaphernes forced the Ionian cities to agree to arrangements under which all property differences were to be settled through references to him. Artaphernes reorganized the land register by measured out their territories in parasangs and assessed their tributes accordingly (Herodotus vi. 42).[2] The Milesian historian and geographer Hecataeus advised him to be lenient so as not to create feelings of resentment amongst the Ionians. It seems that Artaphernes took this advice and was reasonable and merciful to those who had recently revolted against the Persians.[7]

- Execution of Histiaeus

Histiaeus, who had been an instigator of the Ionian revolt, was captured by the Persian general, Harpagus in 493 BC, as he was attempting to land on the mainland to attack the Persians. Artaphernes did not want to send him back to Susa, where he suspected that Darius would pardon him, so he executed him by impaling him, and sent his head to Darius.[8] According to Herodotus, Darius still did not believe Histiaeus was a traitor and gave his head an honourable burial.

In 492 BC Artaphernes was replaced in his satrapy by Mardonius (Herodotus V. 25, 30–32, 35, &c.; Diod. Sic. x. 25).[2]

His son of the same name was appointed, together with Datis, to take command of the expedition sent by Darius to punish Athens and Eretria for their roles in the Ionian revolt. Ten years later, he was in command of the Lydians and Mysians (Herod. vi. 94, 119; Vu. 4, sch. Persae, 21).[2]

Aeschylus, in his list of Persian kings (Persae, 775 ff.), which is quite unhistorical, mentions two kings with the name Artarenes. Aeschylus may actually be referring to both Artaphernes and his son of the same name.[2]

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

Artaphernes derives from the Median: Rta + Farnah (endowed with the Glory of Righteousness[9]). The equivalent to Rta in Middle Persian is Arda-/Ard-/Ord- as seen in names such as Ardabil (Arta vila or Arta city), Artabanus (protected or protecting Arta) and Ordibehesht (the best Arta). Arta is a common prefix for Achaemenid names and means correctness, righteousness and ultimate (divine) truth. Farnah is the Median cognate of Avestan Xvarənah meaning "splendour, glory". Farnah is an important concept to pre-Islamic Persians as it signifies a mystic, divine force that is carried by some important or great individuals. So Artafarnah can be said to mean "splendid truth". The concept of "arta" is also mirrored in the Vedic civilization through the Sanskrit word "ŗtá", or righteousness.

References

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. p. 152. ISBN 978-9004091726.

Approximately at the same time Darius appointed his half-brother Artaphernes (Old Persian: Artafarna, 'with truthful sacredness') as satrap of Lydia.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Meyer, Eduard (1911). "Artaphernes". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 661.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781107009608.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107009608.

- LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book V: Chapters 55‑96.

- CROESUS – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Jona Lendering, "Artaphernes"

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9781107009608.

- Lecoq, P. "ARTAPHRENĒS". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

Sources

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire (Eisenbrauns, 2002)