Wali

A wali (Arabic: وَلِيّ, walīy; plural أَوْلِيَاء, ʾawliyāʾ), the Arabic word which has been variously translated "master", "authority", "custodian", "protector",[1][2] is most commonly used by Muslims to indicate an Islamic saint, otherwise referred to by the more literal "friend of God".[1][3][4]

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

When the Arabic definite article al (ال) is added, it refers to one of the names of God in Islam, Allah – al-Walī (الْوليّ), meaning "the Helper, Friend".

In the traditional Islamic understanding of saints, the saint is portrayed as someone "marked by [special] divine favor ... [and] holiness", and who is specifically "chosen by God and endowed with exceptional gifts, such as the ability to work miracles".[5] The doctrine of saints was articulated by Muslim scholars very early on in Islamic history,[6][7][5][8] and particular verses of the Quran and certain hadith were interpreted by early Muslim thinkers as "documentary evidence"[5] of the existence of saints. Graves of saints around the Muslim world became centers of pilgrimage – especially after 1200 CE – for masses of Muslims seeking their barakah (blessing).[9]

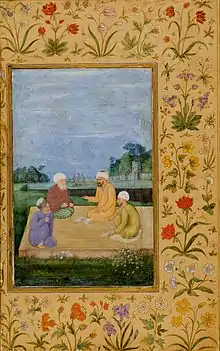

Since the first Muslim hagiographies were written during the period when the Islamic mystical trend of Sufism began its rapid expansion, many of the figures who later came to be regarded as the major saints in orthodox Sunni Islam were the early Sufi mystics, like Hasan of Basra (d. 728), Farqad Sabakhi (d. 729), Dawud Tai (d. 777–781), Rabia of Basra (d. 801), Maruf Karkhi (d. 815), and Junayd of Baghdad (d. 910).[1] From the twelfth to the fourteenth century, "the general veneration of saints, among both people and sovereigns, reached its definitive form with the organization of Sufism ... into orders or brotherhoods".[10] In the common expressions of Islamic piety of this period, the saint was understood to be "a contemplative whose state of spiritual perfection ... [found] permanent expression in the teaching bequeathed to his disciples".[10] In many prominent Sunni creeds of the time, such as the famous Creed of Tahawi (c. 900) and the Creed of Nasafi (c. 1000), a belief in the existence and miracles of saints was presented as "a requirement" for being an orthodox Muslim believer.[11][12]

Aside from the Sufis, the preeminent saints in traditional Islamic piety are the Companions of the Prophet, their Successors, and the Successors of the Successors.[13] Additionally, the prophets and messengers in Islam are also believed to be saints by definition, although they are rarely referred to as such, in order to prevent confusion between them and ordinary saints; as the prophets are exalted by Muslims as the greatest of all humanity, it is a general tenet of Sunni belief that a single prophet is greater than all the regular saints put together.[14] In short, it is believed that "every prophet is a saint, but not every saint is a prophet".[15]

In the modern world, the traditional Sunni and Shia idea of saints has been challenged by puritanical and revivalist Islamic movements such as the Salafi movement, Wahhabism, and Islamic Modernism, all three of which have, to a greater or lesser degree, "formed a front against the veneration and theory of saints".[1] As has been noted by scholars, the development of these movements has indirectly led to a trend amongst some mainstream Muslims to resist "acknowledging the existence of Muslim saints altogether or ... [to view] their presence and veneration as unacceptable deviations".[16] However, despite the presence of these opposing streams of thought, the classical doctrine of saint veneration continues to thrive in many parts of the Islamic world today, playing a vital role in daily expressions of piety among vast segments of Muslim populations in Muslim countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Turkey, Senegal, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Morocco,[1] as well as in countries with substantial Islamic populations like India, China, Russia, and the Balkans.[1]

Names

Regarding the rendering of the Arabic walī by the English "saint", prominent scholars such as Gibril Haddad have regarded this as an appropriate translation, with Haddad describing the aversion of some Muslims towards the use of "saint" for walī as "a specious objection ... for [this is] – like 'Religion' (din), 'Believer' (mu'min), 'prayer' (salat), etc. – [a] generic term for holiness and holy persons while there is no confusion, for Muslims, over their specific referents in Islam, namely: the reality of iman with Godwariness and those who possess those qualities."[17] In Persian, which became the second most influential and widely spoken language in the Islamic world after Arabic,[1] the general title for a saint or a spiritual master became pīr (Persian: پیر, literally "old [person]", "elder"[18]).[1] Although the ramifications of this phrase include the connotations of a general "saint,"[1] it is often used to specifically signify a spiritual guide of some type.[1]

Amongst Indian Muslims, the title pīr baba (पीर बाबा) is commonly used in Hindi to refer to Sufi masters or similarly honored saints.[1] Additionally, saints are also sometimes referred to in the Persian or Urdu vernacular with "Hazrat."[1] In Islamic mysticism, a pīr's role is to guide and instruct his disciples on the mystical path.[1] Hence, the key difference between the use of walī and pīr is that the former does not imply a saint who is also a spiritual master with disciples, while the latter directly does so through its connotations of "elder".[1] Additionally, other Arabic and Persian words that also often have the same connotations as pīr, and hence are also sometimes translated into English as "saint", include murshid (Arabic: مرشد, meaning "guide" or "teacher"), sheikh and sarkar (Persian word meaning "master").[1]

In the Turkish Islamic lands, saints have been referred to by many terms, including the Arabic walī, the Persian s̲h̲āh and pīr, and Turkish alternatives like baba in Anatolia, ata in Central Asia (both meaning "father"), and eren or ermis̲h̲ (< ermek "to reach, attain") or yati̊r ("one who settles down") in Anatolia.[1] Their tombs, meanwhile, are "denoted by terms of Arabic or Persian origin alluding to the idea of pilgrimage (mazār, ziyāratgāh), tomb (ḳabr, maḳbar) or domed mausoleum (gunbad, ḳubba). But such tombs are also denoted by terms usually used for dervish convents, or a particular part of it (tekke in the Balkans, langar, 'refectory,' and ribāṭ in Central Asia), or by a quality of the saint (pīr, 'venerable, respectable,' in Azerbaijan)."[1]

History

According to various traditional Sufi interpretations of the Quran, the concept of sainthood is clearly described.[19] Some modern scholars, however, assert that the Quran does not explicitly outline a doctrine or theory of saints.[1] In the Quran, the adjective walī is applied to God, in the sense of him being the "friend" of all believers (Q2:257). However, particular Quranic verses were interpreted by early Islamic scholars to refer to a special, exalted group of holy people.[5] These included 10:62:[5] "Surely God's friends (awliyāa l-lahi): no fear shall be on them, neither shall they sorrow,"[5] and 5:54, which refers to God's love for those who love him.[5] Additionally, some scholars[1] interpreted 4:69, "Whosoever obeys God and the Messenger, they are with those unto whom God hath shown favor: the prophets and the ṣidīqīna and the martyrs and the righteous. The best of company are they," to carry a reference to holy people who were not prophets and were ranked below the latter.[1] The word ṣidīqīna in this verse literally connotes "the truthful ones" or "the just ones," and was often interpreted by the early Islamic thinkers in the sense of "saints," with the famous Quran translator Marmaduke Pickthall rendering it as "saints" in their interpretations of the scripture.[1] Furthermore, the Quran referred to the miracles of saintly people who were not prophets like Khidr (18:65-82) and the People of the Cave (18:7-26), which also led many early scholars to deduce that a group of venerable people must exist who occupy a rank below the prophets but are nevertheless exalted by God.[1] The references in the corpus of hadith literature to bona fide saints like the pre-Islamic Jurayj̲,[20][21][22][23] only lent further credence to this early understanding of saints.[1]

Collected stories about the "lives or vitae of the saints", began to be compiled "and transmitted at an early stage"[1] by many regular Muslim scholars, including Ibn Abi al-Dunya (d. 894),[1] who wrote a work entitled Kitāb al-Awliyāʾ (Lives of the Saints) in the ninth-century, which constitutes "the earliest [complete] compilation on the theme of God's friends."[1] Prior to Ibn Abi al-Dunya's work, the stories of the saints were transmitted through oral tradition; but after the composition of his work, many Islamic scholars began writing down the widely circulated accounts,[1] with later scholars like Abū Nuʿaym al-Iṣfahānī (d. 948) making extensive use of Ibn Abi al-Dunya's work in his own Ḥilyat al-awliyāʾ (The Adornment of the Saints).[1] It is, moreover, evident from the Kitāb al-Kas̲h̲f wa ’l-bayān of the early Baghdadi Sufi mystic Abu Sa'id al-Kharraz (d. 899) that a cohesive understanding of the Muslim saints was already in existence, with al-Kharraz spending ample space distinguishing between the virtues and miracles (karāmāt) of the prophets and the saints.[1] The genre of hagiography (manāḳib) only became more popular with the passage of time, with numerous prominent Islamic thinkers of the medieval period devoting large works to collecting stories of various saints or to focusing upon "the marvelous aspects of the life, the miracles or at least the prodigies of a [specific] Ṣūfī or of a saint believed to have been endowed with miraculous powers."[24]

In the late ninth-century, important thinkers in Sunni Islam officially articulated the previously-oral doctrine of an entire hierarchy of saints, with the first written account of this hierarchy coming from the pen of al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi (d. 907-912).[1] With the general consensus of Islamic scholars of the period accepting that the ulema were responsible for maintaining the "exoteric" part of Islamic orthodoxy, including the disciplines of law and jurisprudence, while the Sufis were responsible for articulating the religion's deepest inward truths,[1] later prominent mystics like Ibn Arabi (d. 1240) only further reinforced this idea of a saintly hierarchy, and the notion of "types" of saints became a mainstay of Sunni mystical thought, with such types including the ṣiddīqūn ("the truthful ones") and the abdāl ("the substitute-saints"), amongst others.[1] Many of these concepts appear in writing far before al-Tirmidhi and Ibn Arabi; the idea of the abdāl, for example, appears as early as the Musnad of Ibn Hanbal (d. 855), where the word signifies a group of major saints "whose number would remain constant, one always being replaced by some other on his death."[25] It is, in fact, reported that Ibn Hanbal explicitly identified his contemporary, the mystic Maruf Karkhi (d. 815-20), as one of the abdal, saying: "He is one of the substitute-saints, and his supplication is answered."[26]

From the twelfth to the fourteenth century, "the general veneration of saints, among both people and sovereigns, reached its definitive form with the organization of Sufism—the mysticism of Islam—into orders or brotherhoods."[10] In general Islamic piety of the period, the saint was understood to be "a contemplative whose state of spiritual perfection ... [found] permanent expression in the teaching bequeathed to his disciples."[10] It was by virtue of his spiritual wisdom that the saint was accorded veneration in medieval Islam, "and it is this which ... [effected] his 'canonization,' and not some ecclesiastical institution" as in Christianity.[10] In fact, the latter point represents one of the crucial differences between the Islamic and Christian veneration of saints, for saints are venerated by unanimous consensus or popular acclaim in Islam, in a manner akin to all those Christian saints who began to be venerated prior to the institution of canonization.[10] In fact, a belief in the existence of saints became such an important part of medieval Islam[11][12] that many of the most important creeds articulated during the time period, like the famous Creed of Tahawi, explicitly declared it a requirement for being an "orthodox" Muslim to believe in the existence and veneration of saints and in the traditional narratives of their lives and miracles.[14][11][12][3] Hence, we find that even medieval critics of the widespread practice of venerating the tombs of saints, like Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328), never denied the existence of saints as such, with the Hanbali jurist stating: "The miracles of saints are absolutely true and correct, by the acceptance of all Muslim scholars. And the Qur'an has pointed to it in different places, and the sayings of the Prophet have mentioned it, and whoever denies the miraculous power of saints are only people who are innovators and their followers."[27] In the words of one contemporary academic, practically all Muslims of that era believed that "the lives of saints and their miracles were incontestable."[28]

In the modern world, the traditional idea of saints in Islam has been challenged by the puritanical and revivalist Islamic movements of Salafism and Wahhabism, whose influence has "formed a front against the veneration and theory of saints."[1] For the adherents of Wahhabi ideology, for example, the practice of venerating saints appears as an "abomination", for they see in this a form of idolatry.[1] It is for this reason that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which adheres to the Wahhabi creed, "destroyed the tombs of saints wherever ... able"[1] during its expansion in the Arabian Peninsula from the eighteenth-century onwards.[1][Note 1] As has been noted by scholars, the development of these movements have indirectly led to a trend amongst some mainstream Muslims to also resist "acknowledging the existence of Muslim saints altogether or ... [to view] their presence and veneration as unacceptable deviations."[16] At the same time, the movement of Islamic Modernism has also opposed the traditional veneration of saints, for many proponents of this ideology regard the practice as "being both un-Islamic and backwards ... rather than the integral part of Islam which they were for over a millennium."[29] Despite the presence, however, of these opposing streams of thought, the classical doctrine of saint-veneration continues to thrive in many parts of the Islamic world today, playing a vital part in the daily piety of vast portions of Muslim countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Turkey, Senegal, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Tunisia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Morocco,[1] as well as in countries with substantive Islamic populations like India, China, Russia, and the Balkans.[1]

Definitions

The general definition of the Muslim saint in classical texts is that he represents a "[friend of God] marked by [special] divine favor ... [and] holiness", being specifically "chosen by God and endowed with exceptional gifts, such as the ability to work miracles."[5] Moreover, the saint is also portrayed in traditional hagiographies as one who "in some way ... acquires his Friend's, i.e. God's, good qualities, and therefore he possesses particular authority, forces, capacities and abilities."[1] Amongst classical scholars, Qushayri (d. 1073) defined the saint as someone "whose obedience attains permanence without interference of sin; whom God preserves and guards, in permanent fashion, from the failures of sin through the power of acts of obedience."[30] Elsewhere, the same author quoted an older tradition in order to convey his understanding of the purpose of saints, which states: "The saints of God are those who, when they are seen, God is remembered."[31]

Meanwhile, al-Hakim al-Tirmidhi (d. 869), the most significant ninth-century expositor of the doctrine, posited six common attributes of true saints (not necessarily applicable to all, according to the author, but nevertheless indicative of a significant portion of them), which are: (1) when people see him, they are automatically reminded of God; (2) anyone who advances towards him in a hostile way is destroyed; (3) he possesses the gift of clairvoyance (firāsa); (4) he receives divine inspiration (ilhām), to be strictly distinguished from revelation proper (waḥy),[1][32][33] with the latter being something only the prophets receive; (5) he can work miracles (karāmāt) by the leave of God, which may differ from saint to saint, but may include marvels such as walking on water (al-mas̲h̲y ʿalā ’l-māʾ) and shortening space and time (ṭayy al-arḍ); and (6) he associates with Khidr.[34][1] Al-Tirmidhi states, furthermore, that although the saint is not sinless like the prophets, he or she can nevertheless be "preserved from sin" (maḥfūz) by the grace of God.[1] The contemporary scholar of Sufism Martin Lings described the Islamic saints as "the great incarnations of the Islamic ideal.... spiritual giants with which almost every generation was blessed."[35]

Classical testimonies

The doctrine of saints, and of their miracles, seems to have been taken for granted by many of the major authors of the Islamic Golden Age (ca. 700–1400),[1] as well as by many prominent late-medieval scholars.[1] The phenomena in traditional Islam can be at least partly ascribed to the writings of many of the most prominent Sunni theologians and doctors of the classical and medieval periods,[1] many of whom considered the belief in saints to be "orthodox" doctrine.[1] Examples of classical testimonies include:

- "God has saints (awliyā) whom He has specially distinguished by His friendship and whom He has chosen to be the governors of His kingdom… He has made the saints governors of the universe… Through the blessing of their advent the rain falls from heaven, and through the purity of their lives the plants spring up from the earth, and through their spiritual influence the Muslims gain victories over the truth concealers" (Hujwiri [d. 1072-7]; Sunni Hanafi jurist and mystic)[1]

- "The miracles of the saints (awliyā) are a reality. The miracle appears on behalf of the saint by way of contradicting the customary way of things.... And such a thing is reckoned as an evidentiary miracle on behalf of the Messenger to one of whose people this act appears, because it is evident from it that he is a saint, and he could never be a saint unless he were right in his religion; and his religion is the confession of the message of the Messenger" (al-Nasafī [d. 1142], Creed XV; Sunni Hanafi theologian)[36]

- "The miracles of saints are absolutely true and correct, and acknowledged by all Muslim scholars. The Qur’an has pointed to it in different places, and the Hadith of the Prophet have mentioned it, and whoever denies the miraculous power of saints are innovators or following innovators" (Ibn Taymiyya [d. 1328], Mukhtasar al-Fatawa al-Masriyya; Sunni Hanbali theologian and jurisconsult)[37]

Seeking of blessings

The rationale for veneration of deceased saints by pilgrims in an appeal for blessings (Barakah) even though the saints will not rise from the dead until the Day of Resurrection (Yawm ad-Dīn) may come from the hadith that states “the Prophets are alive in their graves and they pray”. (According to the Islamic concept of Punishment of the Grave—established by hadith—the dead are still conscious and active, with the wicked suffering in their graves as a prelude to hell and the pious at ease.) According to Islamic historian Jonathan A.C. Brown, "saints are thought to be no different" than prophets, "as able in death to answer invocations for assistance" as they were while alive.[9]

Types and hierarchy

Saints were envisaged to be of different "types" in classical Islamic tradition.[1] Aside from their earthly differences as regard their temporal duty (i.e. jurist, hadith scholar, judge, traditionist, historian, ascetic, poet), saints were also distinguished cosmologically as regards their celestial function or standing.[1] In Islam, however, the saints are represented in traditional texts as serving separate celestial functions, in a manner similar to the angels, and this is closely linked to the idea of a celestial hierarchy in which the various types of saints play different roles.[1] A fundamental distinction was described in the ninth century by al-Tirmidhi in his Sīrat al-awliyāʾ (Lives of the Saints), who distinguished between two principal varieties of saints: the walī ḥaḳḳ Allāh on the one hand and the walī Allāh on the other.[1] According to the author, "the [spiritual] ascent of the walī ḥaḳḳ Allāh must stop at the end of the created cosmos ... he can attain God's proximity, but not God Himself; he is only admitted to God's proximity (muḳarrab). It is the walī Allāh who reaches God. Ascent beyond God's throne means to traverse consciously the realms of light of the Divine Names.... When the walī Allāh has traversed all the realms of the Divine Names, i.e. has come to know God in His names as completely as possible, he is then extinguished in God's essence. His soul, his ego, is eliminated and ... when he acts, it is God Who acts through him. And so the state of extinction means at the same time the highest degree of activity in this world."[1]

Although the doctrine of the hierarchy of saints is already found in written sources as early as the eighth-century,[1] it was al-Tirmidhi who gave it its first systematic articulation.[1] According to the author, forty major saints, whom he refers to by the various names of ṣiddīḳīn, abdāl, umanāʾ, and nuṣaḥāʾ,[1] were appointed after the death of Muhammad to perpetuate the knowledge of the divine mysteries vouchsafed to them by the prophet.[1] These forty saints, al-Tirmidhi stated, would be replaced in each generation after their earthly death; and, according to him, "the fact that they exist is a guarantee for the continuing existence of the world."[1] Among these forty, al-Tirmidhi specified that seven of them were especially blessed.[1] Despite their exalted nature, however, al-Tirmidhi emphasized that these forty saints occupied a rank below the prophets.[1] Later important works which detailed the hierarchy of saints were composed by the mystic ʿAmmār al-Bidlīsī (d. between 1194 and 1207), the spiritual teacher of Najmuddin Kubra (d. 1220), and by Ruzbihan Baqli (d. 1209), who evidently knew of "a highly developed hierarchy of God's friends."[1] The differences in terminology between the various celestial hierarchies presented by these authors were reconciled by later scholars through their belief that the earlier mystics had highlighted particular parts and different aspects of a single, cohesive hierarchy of saints.[1]

Sufism

In certain esoteric teachings of Islam, there is said to be a cosmic spiritual hierarchy[38][39][40] whose ranks include walis (saints, friends of God), abdals (changed ones), headed by a ghawth (helper) or qutb (pole, axis). The details vary according to the source.

One source is the 12th Century Persian Ali Hujwiri. In his divine court, there are three hundred akhyār ("excellent ones"), forty abdāl ("substitutes"), seven abrār ("piously devoted ones"), four awtād ("pillars"), three nuqabā ("leaders") and one qutb.

All these saints know one another and cannot act without mutual consent. It is the task of the Awtad to go round the whole world every night, and if there should be any place on which their eyes have not fallen, next day some flaw will appear in that place, and they must then inform the Qutb in order that he may direct his attention to the weak spot and that by his blessings the imperfection may be remedied.[41]

Another is from Ibn Arabi, who lived in Moorish Spain. It has a more exclusive structure. There are eight nujabā ("nobles"), twelve nuqabā, seven abdāl, four awtād, two a’immah ("guides"), and the qutb.[42]

According to the 20th-century Sufi Inayat Khan, there are seven degrees in the hierarchy. In ascending order, they are pir, buzurg, wali, ghaus, qutb, nabi and rasul He does not say how the levels are populated. Pirs and buzurgs assist the spiritual progress of those who approach them. Walis may take responsibility for protecting a community and generally work in secret. Qutbs are similarly responsible for large regions. Nabis are charged with bringing a reforming message to nations or faiths, and hence have a public role. Rasuls likewise have a mission of transformation of the world at large.[43]

Regional veneration

The amount of veneration a specific saint received varied from region to region in Islamic civilization, often on the basis of the saint's own history in that region.[1] While the veneration of saints played a crucial role in the daily piety of Sunni Muslims all over the Islamic world for more than a thousand years (ca. 800–1800), exactly which saints were most widely venerated in any given cultural climate depended on the hagiographic traditions of that particular area.[1] Thus, while Moinuddin Chishti (d. 1236), for example, was honored throughout the Sunni world in the medieval period, his cultus was especially prominent in the Indian subcontinent, as that is where he was believed to have preached, performed the majority of his miracles, and ultimately settled at the end of his life.[1]

North Africa

The veneration of saints has played "an essential role in the religious, and social life of the Maghreb for more or less a millennium”;[1] in other words, since Islam first reached the lands of North Africa in the eighth century.[1] The first written references to ascetic Muslim saints in Africa, "popularly admired and with followings,"[1] appear in tenth-century hagiographies.[1][44] As has been noted by scholars, however, "the phenomenon may well be older,"[1] for many of the stories of the Islamic saints were passed down orally before finally being put to writing.[1] One of the most widely venerated saints in early North African Islamic history was Abū Yaʿzā (or Yaʿazzā, d. 1177), an illiterate Sunni Maliki miracle worker whose reputation for sanctity was admired even in his own life.[1][45][46] Another immensely popular saint of the time-period was Ibn Ḥirzihim (d. 1163), who also gained renown for his personal devoutness and his ability to work miracles.[1] It was Abu Madyan (d. 1197), however, who eventually became one of the Awliya Allah of the entire Maghreb. A "spiritual disciple of these two preceding saints,"[1] Abū Madyan, a prominent Sunni Maliki scholar, was the first figure in Maghrebi Sufism "to exercise an influence beyond his own region."[1] Abū Madyan travelled to the East, where he is said to have met prominent mystics like the renowned Hanbali jurist Abdul-Qadir Gilani (d. 1166).[1] Upon returning to the Maghreb, Abū Madyan stopped at Béjaïa and "formed a circle of disciples."[1] Abū Madyan eventually died in Tlemcen, while making his way to the Almohad court of Marrakesh; he was later venerated as a prime Awliya Allah of Tlemcen by popular acclaim.[1][47][48]

One of Abū Madyan's most notable disciples was ʿAbd al-Salām Ibn Mas̲h̲īs̲h̲ (d. 1127),[1] a "saint ... [who] had a posthumous fame through his being recognised as a master and a 'pole' by" Abu ’l-Ḥasan al-S̲h̲ād̲h̲ilī (d. 1258).[1] It was this last figure who became the preeminent saint in Maghrebi piety, due to his being the founder of one of the most famous Sunni Sufi orders of North Africa: the Shadhiliyya tariqa.[1] Adhering to the Maliki maddhab in its jurisprudence, the Shadhili order produced numerous widely honored Sunni saints in the intervening years, including Fāsī Aḥmad al-Zarrūq (d. 1494),[1] who was educated in Egypt but taught in Libya and Morocco, and Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad al-Jazūlī (d. 1465), "who returned to Morocco after a long trip to the East and then began a life as a hermit,"[1] and who achieved widespread renown for the miracles he is said to have wrought by the leave of God.[1] Eventually, the latter was buried in Marrakesh, where he ended up becoming of the city's seven most famous Awliya Allah for the Sunnis of the area.[1] Some of the most popular and influential Maghrebi saints and mystics of the following centuries were Muḥammad b. Nāṣir (d. 1674), Aḥmad al-Tij̲ānī (d. 1815), Abū Ḥāmid al-ʿArabī al-Darqāwī (d. 1823), and Aḥmad b. ʿAlāwī (d. 1934),[49] with the latter three originating Sufi orders of their own.[1] Famous adherents of the Shadhili order amongst modern Islamic scholars include Abdallah Bin Bayyah (b. 1935), Muhammad Alawi al-Maliki (d. 2004), Hamza Yusuf (b. 1958), and Muhammad al-Yaqoubi (b. 1963).[1]

The veneration of saints in Maghrebi Sunni Islam has been studied by scholars with regard to the various "types" of saints venerated by Sunnis in those areas.[1] These include:

- (1) the "pure, ascetic hermit,"[1] who is honored for having refused all ostentation, and is commemorated not on account of his written works but by virtue of the reputation he is believed to have had for personal sanctity, miracles, and "inward wisdom or gnosis";[1]

- (2) "the ecstatic and eccentric saint" (mad̲j̲d̲h̲ūb),[1] who is believed to have maintained orthodoxy in his fulfillment of the pillars of the faith, but who is famous for having taught in an unusually direct style or for having divulged the highest truths before the majority in a manner akin to Hallaj (d. 922).[1] Famous and widely venerated saints of this "type" include Ibn al-Marʾa (d. 1214), ʿAlī al-Ṣanhāj̲ī (ca. 16th-century), ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mad̲j̲d̲h̲ūb (literally "ʿAbd al-Raḥmān the Ecstatic", d. 1569);[50]

- (3) the "warrior saint" (pl. murābiṭūn) or martyr;[1]

- (4) female saints, who may belong to one of the aforementioned three categories or some other.[1] It has been remarked that "Maghrebi sainthood is by no means confined to men, and ... some of the tombs of female saints are very frequently visited."[1]

- (5) "Jewish saints", that is to say, venerable Jewish personages whose tombs are frequented by Sunni Muslims in the area for the seeking of blessings[1]

Regarding the veneration of saints amongst Sunni Muslims in the Maghreb in the present day, scholars have noted the presence of many "thousands of minor, local saints whose tombs remain visible in villages or the quarters of towns."[1] Although many of these saints lack precise historiographies or hagiographies, "their presence and their social efficacity ... [are] immense"[1] in shaping the spiritual life of Muslims in the region. For the vast majority of Muslims in the Maghreb even today, the saints remain "very much alive at their tomb, to the point that the person's name most often serves to denote the place."[1] While this classical type of Sunni veneration represents the most widespread stance in the area, the modern influence of Salafism and Wahhabism have challenged the traditional practice in some quarters.[1]

Turkey, the Balkans, the Caucasus and Azerbaijan

Scholars have noted the tremendously "important role"[1] the veneration of saints has historically played in Islamic life all these areas, especially amongst Sunnis who frequent the many thousands of tombs scattered throughout the region for blessings in performing the act of ziyāra.[1] According to scholars, "between the Turks of the Balkans and Anatolia, and those in Central Asia, despite the distance separating them, the concept of the saint and the organisation of pilgrimages displays no fundamental differences."[1] The veneration of saints really spread in the Turkish lands from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries,[1] and played a crucial role in medieval Turkic Sunni piety not only in cosmopolitan cities but also "in rural areas and amongst nomads of the whole Turkish world."[1] One of the reasons proposed by scholars for the popularity of saints in pre-modern Turkey is that Islam was majorly spread by the early Sunni Sufis in the Turkish lands, rather than by purely exoteric teachers.[1] Most of the saints venerated in Turkey belonged to the Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence.[1]

As scholars have noted, saints venerated in traditional Turkish Sunni Islam may be classified into three principal categories:[1]

- (1) The g̲h̲āzīs or early Muslims saints who preached the faith in the region and were often martyred for their religion. Some of the most famous and widely venerated saints of this category include the prophet Muhammad's companion Abū Ayyūb al-Anṣārī (d. 674), who was killed beneath the walls of Constantinople and was honored as a martyr shortly thereafter,[1] and Sayyid Baṭṭāl G̲h̲āzī (d. ninth-century), who fought the Christians in Anatolia during the Umayyad period.[1]

- (2) Sufi saints, who were most often Sunni mystics who belonged to the Hanafi school of Sunni jurisprudence and were attached to one of the orthodox Sufi orders like the Naqshbandi or the Mevlevi.[1]

- (3) The "greats figures of Islam", both pre-Islamic and those who came after Muhammad, as well as certain sainted rulers.[1]

Reverence of Awliya Allah

Reverence for Awliya Allah have been an important part of both Sunni and Shia Islamic tradition that particularly important classical saints have served as the heavenly advocates for specific Muslim empires, nations, cities, towns, and villages.[51] With regard to the sheer omnipresence of this belief, the late Martin Lings wrote: "There is scarcely a region in the empire of Islam which has not a Sufi for its Patron Saint."[52] As the veneration accorded saints often develops purely organically in Islamic climates, the Awliya Allah are often recognized through popular acclaim rather than through official declaration.[51] Traditionally, it has been understood that the Wali'Allah of a particular place prays for that place's well-being and for the health and happiness of all who live therein.[51] Here is a partial list of Muslim Awliya Allah:

| Country | Awliya Allah | Life dates | Notes | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanā'ī | d. 1131/1141 | Sunni mystic, Sufi poet | ||

| Abū Madyan | d. 1197–98 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Tlemcen; in the words of one scholar, "the city has grown and developed under the beneficent aegis of the great saint, and the town of al-ʿUbbād has grown up round his tomb"[53] | |

| ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-T̲h̲aʿālibī | d. c. 1200 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Algiers[54] | |

| Shah Jalal | d. 1347 | Sufi saint and mystic of the Suhrawardiyya order, born in modern-day Turkey he travelled to the Indian subcontinent and settled in the North-East Bengal and Assam spreading Islam across the area and became the main guide to the new Muslim population of Eastern Bengal. | ||

| Khan Jahan Ali | d. 1459 | Born in modern Uzbekistan, he travelled to southern Bengal to spread Islam; he built the mosque city of Bagerhat and cleared the Sunderbans for human settlement. He developed southern Bengal by linking Bagerghat to the trade city of Chittagong and Sonargaon and introduced Islamic education there. | ||

| Akhi Siraj Aainae Hind | d. 14 century | Sufi saint (born in Gaur, West Bengal) of the Chishti order, he spread Islam across Northern Bengal and Western Bihar, he was also the administrator of Northern Bengal under the Sultan Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah developing the area. His dargah in Malda is one of the largest in South Asia and gathers thousands a year. | ||

| Abu’l-Ḥasan al-S̲h̲ād̲h̲ilī | d. 1258 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence and founder of the Shadiliyya tariqa | Many parts of Upper Egypt, but particularly among the ʿAbābda tribe[55] | |

| Abū l-Ḥajjāj of Luxor | d. 1244 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Luxor[56] | |

| ʿAbd al-Raḥīm of Qena | d. 1196 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence, and famous defender of orthodoxy in the area | City of Qena[56] | |

| Abādir ʿUmar al-Riḍā | d. c. 1300 | Sunni mystic of Shafi'i jurisprudence | City of Harar; according to one scholar, "Harar later came to be known as Madīnat al-Awliyāʾ ('the city of saints') for the shrines of hundreds of saints in and around Harar"[57] | |

| Abū Barakāt Yūsuf Al-Kawnayn Al-Barbari | d. c. 1200 | Sunni saint and scholar of Shafi'i jurisprudence. He is considered the forefather of the Walashma Dynasty. | Travelled a lot from Harar, Zeila, Baghdad, Dhogor and even Maldives, where he spread Islam. | |

| Ash-Shaykh Diyā Ud-Dīn Ishāq Ibn Ahmad Ar-Ridhāwi Al-Maytī | d. c. 1300 | Sunni scholar and traveler of Husaynid lineage. He is the eponymous ancestor of the isaaq clan-family. | Travelled from Hijāz, to Yaman, Bilād Al-Habasha and finally the city of Maydh. | |

| Niẓām al-Dīn Awliyā | d. 1325 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | City of Delhi[58] | |

| S̲h̲āh al-Ḥamīd ʿAbd al-Ḳādir | ob. 1600 | Sunni mystic of Shafi'i jurisprudence | Town of Nagore[59] | |

| Chishtī Muʿīn al-Dīn Ḥasan Sijzī | Mystic of Chishti order | City of Ajmer | ||

| Bābā Nūr al-Dīn Ris̲h̲ī | d. 1377 | Sunni ascetic and mystic | town of Bijbehara[60][61][62] | |

| Daniel | d. 600 BCE | Hebrew prophet who is venerated in Islamic tradition | City of Shush, where the most popular shrine devoted to him is located | |

| Husayn ibn Ali | d. 680 | grandson of Muhammad and Third imam for Shia Muslims | All Iraq for both Shia and Sunni Muslims, but especially the city of Karbala | |

| ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī | d. 1166 | Sunni mystic and jurist of Hanbali jurisprudence and founder of the Qadiriyya tariqa | All Iraq in classical Sunni piety, but especially the city of Baghdad[63] | |

| Aḥmad Yesewī | d. 1166 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence and founder of the Yesewīyya tariqa | All of Kazakhstan; additionally, venerated as the Wali of all the modern nation states comprising the pre-modern Turkestan[64] | |

| Abū S̲h̲uʿayb Ayyūb b. Saʿīd al-Ṣinhāj̲ī (in the vernacular "Mūlāy Būs̲h̲ʿīb") | d. c. 1100 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Azemmour[65] | |

| Ḥmād u-Mūsā | d. 1563 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence and the Shadiliyya tariqa | Region of Sous[66] | |

| Aḥmad b. Jaʿfar al-Ḵh̲azrajī Abu ’l-ʿAbbās al-Sabtī | d. 1205 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Marrakesh | |

| Sidi Belliūt | d. c. 1500 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Casablanca[67] | |

| Ibn ʿĀs̲h̲ir | d. 1362–63 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Salé[68] | |

| Abū Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ |d. 1500 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Safi[69] | ||

| Mūlāy ʿAlī Bū G̲h̲ālem | d. 1200 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | Town of Alcazarquivir | |

| Idris I of Morocco | d. 791 | First Islamic ruler and founder of the Idrisid dynasty | City of Fez[70] | |

| ʿAbd al-Ḳādir Muḥammad | d. c. 1500 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | Town of Figuig[71] | |

| Muḥammad b. ʿĪsā | d. 16th century | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Meknes[72] | |

| ʿAbd Allāh S̲h̲āh G̲h̲āzī | d. c. 800 | Early Muslim mystic and preacher | City of Karachi[73] | |

| Abu 'l-Ḥasan Ali Huj̲wīrī | d. 1072–1077 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence; often referred to as Dātā Ganj̲bak̲h̲s̲h̲ by Pakistanis | City of Lahore[74] | |

| ʿAbd Allāh S̲h̲āh Qādri | d. 1757 | Muslim Sufi poet and philosopher of Qadiriyya tariqa | City of Kasur | |

| Bahāʾ al-Dīn Zakarīyā | d. 1170 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence and the Suhrawardiyya tariqa | Vast areas of south-west Punjab and Sindh | |

| Lāl Shāhbāz Q̣alandar | d. 1275 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | City of Sehwan Sharif] | |

| Bilāwal S̲h̲āh Nūraniʾ | d. ? | Sufi mystic buried in Lahoot Lamakan | City of Khuzdar] | |

| S̲h̲āh Qabūl ʾAwliyāʾ | d. 1767 | Sunni mystic and pir | City of Peshawar | |

| Jalālʾ al-Dīn Surk͟h Poṣ | d. 1295 | Sufi saint and missionary | City of Uch Sharif | |

| Arslān of Damascus | d. 1160–1164 | Sunni mystic | City of Damascus[75] | |

| Muḥriz b. K̲h̲alaf | d. 1022 | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Tunis[76] | |

| Sīdī al-Māzarī | d. 1300 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | City of Monastir[77] | |

| ʿAbd Allāh Abu ’l-Jimāl | d. 1500 [?] | Sunni mystic of Maliki jurisprudence | city of Khroumire[78] | |

| Boulbaba | d. 7th century | According to tradition, a companion of Muhammad | City of Gabès | |

| Ḥājjī Bayrām Walī | d. 1429–30 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | City of Ankara[79] | |

| Emīr Sulṭān | d. 1455 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | City of Bursa[80] | |

| Miskin Baba | d. 1858–59 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | Island of Ada Kaleh, which was at one time under the control of the Ottoman Empire; island was submerged in 1970 during the construction of the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station[81] | |

| Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Rūmī | d. 1273 | Hanafi mystic of Maturidi creed | City of Konya] | |

| Qutham b. ʿAbbās | d. 676 | Early Muslim martyr | City of Samarkand[82] | |

| Zangī Ātā | d. 1269 | Sunni mystic of Hanafi jurisprudence | City of Tashkent[83] | |

| Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Bā ʿAlāwī | d. 1255 | Sunni mystic of Shafi'i jurisprudence and founder of the ʿAlāwiyya tariqa in Hadhramaut | Region of Hadhramaut[84] | |

| S̲h̲aik̲h̲ Ṣadīq | d. 1500 [?] | Sunni mystic | City of Al Hudaydah | |

| ʿAlī b. ʿUmar al-S̲h̲ād̲h̲ilī | d. 1400 [?] | Sunni mystic of the Shadiliyya tariqa | Port-city of Mokha | |

| Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs | d. 1508 | Sunni mystic of Shafi'i jurisprudence | City of Aden[85] |

See also

References

Notes

- For further informations, see the articles Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Demolition of al-Baqi, Destruction of early Islamic heritage sites in Saudi Arabia, and Persecution of Sufis.

Citations

- Radtke, B.; Lory, P.; Zarcone, Th.; DeWeese, D.; Gaborieau, M.; Denny, F. M.; Aubin, F.; Hunwick, J. O.; Mchugh, N. (2012) [1993]. "Walī". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1335. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- Hans Wehr, p. 1289

- John Renard, Friends of God: Islamic Images of Piety, Commitment, and Servanthood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008); John Renard, Tales of God Friends: Islamic Hagiography in Translation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), passim.

- Kramer, Robert S.; Lobban, Richard A., Jr.; Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Sudan. Historical Dictionaries of Africa (4 ed.). Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-8108-6180-0. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

QUBBA. The Arabic name for the tomb of a holy man ... A qubba is usually erected over the grave of a holy man identified variously as wali (saint), faki, or shaykh since, according to folk Islam, this is where his baraka [blessings] is believed to be strongest ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Radtke, B., "Saint", in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

- J. van Ess, Theologie und Gesellschaft im 2. und 3. Jahrhundert Hidschra. Eine Geschichte des religiösen Denkens im frühen Islam, II (Berlin-New York, 1992), pp. 89–90

- B. Radtke and J. O’Kane, The Concept of Sainthood in Early Islamic Mysticism (London, 1996), pp. 109–110

- B. Radtke, Drei Schriften des Theosophen von Tirmid̲, ii (Beirut-Stuttgart, 1996), pp. 68–69

- Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 59. ISBN 978-1780744209. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam: Language and Meaning (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2009), p. 99

- Jonathan A. C. Brown, "Faithful Dissenters: Sunni Skepticism about the Miracles of Saints", Journal of Sufi Studies 1 (2012), p. 123

- Christopher Taylor, In the Vicinity of the Righteous (Leiden: Brill, 1999), pp. 5–6

- Martin Lings, What is Sufism? (Lahore: Suhail Academy, 2005; first imp. 1983, second imp. 1999), pp. 36–37, 45, 102, etc.

- Al-Ṭaḥāwī, Al-ʿAqīdah aṭ-Ṭaḥāwiyya XCVIII–IX

- Reza Shah-Kazemi, "The Metaphysics of Interfaith Dialogue", in Paths to the Heart: Sufism and the Christian East, ed. James Cutsinger (Bloomington: World Wisdom, 2002), p. 167

- Christopher Taylor, In the Vicinity of the Righteous (Leiden: Brill, 1999), pp. 5–6

- "Shaykh Gibril Fouad Haddad on Facebook". Facebook. Archived from the original on 2022-04-30.

- Newby, Gordon (2002). A Concise Encyclopedia of Islam (1st ed.). Oxford: One World. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-85168-295-9.

- Muhammad Hisham Kabbani (2003), Classical Islam and the Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition, ISBN 9781930409101

- Buk̲h̲ārī. Saḥīḥ al-ʿamal fi ’l-ṣalāt, Bāb 7, Maẓālim, Bāb 35

- Muslim (Cairo 1283), v, 277

- Maḳdisī, al-Badʾ wa ’l-taʾrīk̲h̲, ed. Huart, Ar. text 135

- Samarḳandī, Tanbīh, ed. Cairo 1309, 221

- Pellat, Ch., "Manāḳib", in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Christopher Melchert, The Ḥanābila and the Early Sufis, Arabica, T. 48, Fasc. 3 (Brill, 2001), p. 356

- Gibril F. Haddad, The Four Imams and Their Schools (London: Muslim Academic Trust, 2007), p. 387

- Ibn Taymiyyah, al-Mukhtasar al-Fatawa al-Masriyya, 1980, p. 603

- Josef W. Meri, The Cult of Saints among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 68

- Juan Eduardo Campo, Encyclopedia of Islam (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009), p. 600

- Ibn `Abidin, Rasa'il, 2:277

- Abū’l-Qāsim al-Qushayrī, Laṭā'if al-Isharat bi-Tafsīr al-Qur'ān, tr. Zahra Sands (Louisville: Fons Vitae; Amaan: Royal Aal-al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, 2015), p. 79

- Martin Lings, Return to the Spirit (Lahore: Suhail Academy, 2005), p. 20

- Martin Lings, Mecca: From Before Genesis Until Now (London: Archetype, 2004), p. 1

- B. Radtke and J. O’Kane, The Concept of Sainthood in Early Islamic Mysticism (London, 1996), pp. 124-125

- Martin Lings, "Proofs of Islam", Ilm Magazine, Volume 10, Number 1, December 1985, pp. 3-8

- Earl Edgar Elder (ed. and trans.), A Commentary on the Creed of Islam (New York: Columbia University Press, 1950), p. 136

- Ibn Taymiyyah, Mukhtasar al-Fatawa al-Masriyya (al-Madani Publishing House, 1980), p. 603

- Renard, J: Historical Dictionary of Sufism, p 262

- Markwith, Zachary (14 July 2011). "The Imam and the Qutb: The Axis Mundi in Shiism and Sufism". Majzooban Noor. Nematollahi Gonabadi Sufi Order News Agency. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Staff. "The Saints of Islam". sunnirazvi.net. Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- Staff. "The Saints of Islam". sunnirazvi.net. Retrieved 2012-09-25. Quoting The Mystics of Islam by Reynold A. Nicholson

- Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. p. 8821. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.

- The Spiritual Hierarchy, from the Spiritual Message of Hazrat Inayat Khan

- H.R. Idris (ed.), Manâqib d'Abû Ishâq al-Jabnyânî et de Muhriz b. Khalaf, Paris 1959

- Y. Lobignac, "Un saint berbère, Moulay Ben Azza", in Hésperis, xxxi [1944]

- E. Dermenghem, Le culte des saints dans l'Islam maghrébin, Paris 1954, 1982 [second edition])

- A. Bel, "Sidi Bou Medyan et son maître Ed-Daqqâq à Fès", in Mélanges René Basset, Paris 1923, i, 30-68

- C. Addas, "Abū Madyan and Ibn ʿArabī", in Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi: A Commemorative Volume, Shaftesbury 1993

- M. Lings, A Moslem saint of the twentieth century, Shaikh Ahmad al-ʿAlawī, London 1961, Fr. tr. Un saint musulman du 20 e siècle, le cheikh Ahmad al-ʿAlawī, Paris 1984

- A.L. de Premare, Sîdî ʿAbder-Rahmân al-Medjdûb, Paris-Rabat 1985

- Martin Lings, What is Sufism? (Lahore: Suhail Academy, 2005; first imp. 1983, second imp. 1999), pp. 119–120 etc.

- Martin Lings, What is Sufism? (Lahore: Suhail Academy, 2005; first imp. 1983, second imp. 1999), p. 119

- Bel, A., "Abū Madyan", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Tourneau, R. le, "al-D̲j̲azāʾir", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Hillelson, S., "ʿAbābda", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Gril, Denis, "ʿAbd al-Raḥīm al-Qināʾī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Desplat, Patrick, "Harar", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Hardy, P., "Amīr K̲h̲usraw", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Gazetteer of the Tanjore District, p. 243; cited in Arnold, T. W., "Labbai", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Hasan, Mohibbul, "Bābā Nūr al-Dīn Ris̲h̲ī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Abū ’l Faḍl, Āʾīn-i Akbarī, ii, tr. Blochmann, Calcutta 1927

- Mohibbul Hasan, Kas̲h̲mīr under the Sultans, Calcutta 1959

- Luizard, Pierre-Jean, "Barzinjīs", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Barthold, W., "Turkistān", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Lévi-Provençal, E., "Abū Yaʿazzā", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Faure, A., "Ḥmād U-mūsā", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Yver, G., "Dar al-Bēḍā", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Faure, A., "Ibn ʿĀs̲h̲ir", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs; cf. Lévi-Provençal, Chorfa, 313–14. Ibn Ḳunfud̲h̲, Uns al-faḳīr wa ʿizz al-ḥaḳīr, ed. M. El Fasi and A. Faure, Rabat, 1965, 9-10.

- Deverdun, G., "Glāwā", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M., "al-Tidjānī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Despois, J., "Figuig", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Funck-Brentano, C., "Meknes", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Hasan, Arif (27 April 2014). "Karachi's Densification". Dawn. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

The other site is the over 1,200-year-old tomb of Ghazi Abdullah Shah, a descendant of Imam Hasan. He has become a Wali of Karachi and his urs is an important event for the city and its inhabitants.

- Hosain, Hidayet and Massé, H., "Hud̲j̲wīrī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Geoffroy, Eric, "Arslān al-Dimashqī, Shaykh", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Pellat, Ch., "Muḥriz b. K̲h̲alaf", in Encyclopaedia of Islam 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Marçais, Georges, "Monastir", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Talbi, M., "K̲h̲umayr", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Ménage, V. L., "Ḥād̲jd̲j̲ī Bayrām Walī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Mordtmann, J. H., "Emīr Sulṭān", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed. (1913–1936), Edited by M. Th. Houtsma, T. W. Arnold, R. Basset, R. Hartmann.

- Gradeva, Rossitsa, "Adakale", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Paul, Jürgen, "Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf al-Hamadānī", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Zarcone, Th., "Zangī Ātā", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs.

- Alatas, Ismail Fajrie, "ʿAlāwiyya (in Ḥaḍramawt)", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

- Knysh, Alexander D., "Bā Makhrama ʿUmar", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson.

Further reading

Primary

- Ibn Abi ’l-Dunyā, K. al-Awliyāʾ, in Mad̲j̲mūʿat rasāʾil, Cairo 1354/1935

- Abū Nuʿaym al-Iṣbahānī, Ḥilyat al-awliyāʾ, Cairo 1351 ff./1932 ff.

- Abū Saʿīd al-K̲h̲arrāz, K. al-Kas̲h̲f wa ’l-bayān, ed. Ḳ. al-Sāmarrāʾī, Bag̲h̲dād 1967

- al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmid̲h̲ī, K. K̲h̲atm al-awliyāʾ, ed. O. Yaḥyā, Beirut 1965

- idem, K. Sīrat al-awliyāʾ, ed. B. Radtke, in Drei Schrijten, i, 1-134, Beirut 1992

- idem, al-Farḳ bayn al-āyāt wa ’l-karāmāt, ms. Ankara, Ismail Saib i, 1571, fols. 152b-177b

- idem, Badʾ s̲h̲aʾn Abī ʿAbd Allāh, ed. Yaḥyā, in Tirmid̲h̲ī, K̲h̲atm, 14-32, facs. and German tr. in Radtke, Tirmid̲iana minora, 244-77, Eng. tr. in Radtke and O’Kane, Concept of sainthood, 15-36. Handbooks.

- Bādisī, "al-Maḳṣad", tr. G. Colin, in Archives marocaines, xxvi-xxvii (1926)

- G̲h̲ubrīnī, ʿUnwān al-dirāya, Algiers 1970

- Hud̲j̲wīrī, Kas̲h̲f al-maḥd̲j̲ūb, ed. V. Zhukovsky, repr. Tehran 1336/1958, 265 ff., tr. Nicholson, The Kashf al-mahjūb. The oldest Persian treatise on Sufism, Leiden-London 1911, 210-41

- Kalābād̲h̲ī, al-Taʿarruf li-mad̲h̲hab ahl al-taṣawwuf ed. Arberry, Cairo 1934, tr. idem, The doctrine of the Sufis, 2, Cambridge 1977, ch. 26

- Sarrād̲j̲, K. al-Lumaʿ fi ’l-taṣawwuf, ed. Nicholson, Leiden-London 1914, 315-32, Ger. tr. R. Gramlich, Schlaglichter über das Sufitum, Stuttgart 1990, 449-68

- Abū Ṭālib al-Makkī, Ḳūt al-ḳulūb, Cairo 1932, Ger. tr. Gramlich, Die Nährung der Herzen, Wiesbaden 1992–95, index, s.v. Gottesfreund

- Ḳus̲h̲ayrī, Risāla, many eds., Ger. tr. Gramlich, Das Sendschreiben al-Qušayrīs, Wiesbaden 1989, index, s.v. Gottesfreund

- ʿAmmār al-Bidlīsī, Zwei mystische Schriften, ed. E. Badeen, forthcoming Beirut

- Ibn al-ʿArabī, al-Futūḥāt al-makkiyya, Cairo 1329–1911.

- idem, Rūḥ al-ḳuds, Damascus 1964, Eng. tr. R.W. Austin, The Sufis of Andalusia, London 1971, Fr. tr. G. Leconte, Les Soufies d'Andalousie, Paris 1995

- F. Meier, Die Vita des Scheich Abū Isḥāq al-Kāzarūnī, Leipzig 1948

- Muḥammad b. Munawwar, Asrār al-tawḥīd fī maḳāmāt al-S̲h̲ayk̲h̲ Abī Saʿīd, ed. Muḥammad S̲h̲afīʿī-i Kadkanī, Tehran 1366-7, Eng. tr. J. O’Kane, The secrets of God's mystical oneness, New York 1992

- ʿAzīz al-Dīn Nasafī, K. al-Insān al-kāmil, ed. M. Mole, Tehran-Paris 1962, 313-25

- Ibn Taymiyya, al-Furḳān bayna awliyāʾ al-Raḥmān wa-awliyāʾ al-S̲h̲ayṭān, Cairo 1366/1947

- idem, Ḥaḳīḳat mad̲h̲hab al-ittiḥādiyyīn, in Mad̲j̲mūʿat al-Rasāʾil wa ’l-masāʾil, iv, Cairo n.d., 1 ff.

- Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh, Laṭāʾif al-minan, Fr. tr. E. Geoffroy, La sagesse des maîtres soufis, Paris 1998

Secondary

- Henri Corbin, En Islam iranien, esp. iii, Paris 1972

- Michel Chodkiewicz, Le sceau des saints, Paris 1986

- Jahrhundert Hidschra. Eine Geschichte des religiösen Denkens im frühen Islam, i-vi, Berlin-New York 1991-7

- B. Radtke and J. O’Kane, The concept of sainthood in early Islamic mysticism, London 1996

- Radtke, Drei Schriften des Theosophen von Tirmid̲, i, Beirut-Stuttgart 1992, ii, Beirut-Stuttgart 1996

- R. Mach, Der Zaddik in Talmud und Midrasch, Leiden 1957

- Radtke, "Tirmid̲iana minora", in Oriens, xxxiv (1994), 242-98

- Gramlich, Die Wunder der Freunde Gottes, Wiesbaden 1987

- idem, Die schiitischen Derwischorden Persiens, Wiesbaden 1965–81, ii, 160-5 (on the hierarchy of saints)

- C. Ernst, Ruzbihan Baqli, London 1996

- Radtke, "Zwischen Traditionalisms und Intellektualismus. Geistesgeschichtliche und historiografische Bemerkungen zum Ibrīz des Aḥmad b. al-Mubārak al-Lamaṭī", in Built on solid rock. Festschrift für Ebbe Knudsen, Oslo 1997, 240-67

- H.S. Nyberg, Kleinere Schriften des Ibn al-ʿArabī, Leiden 1919, 103-20

- A. Afifi, The mystical philosophy of Muhyid-din Ibnul-ʿArabi, Cambridge 1939

- W. Chittick, The Sufi path of knowledge, Albany 1989

- Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, The Tijaniyya. A Sufi order in the modern world, London 1965

- Radtke, "Lehrer-Schüler-Enkel. Aḥmad b. Idrīs, Muḥammad ʿUt̲mān al-Mīrġanī, Ismāʿīl al-Walī", in Oriens, xxxiii (1992), 94-132

- I. Goldziher, "Die Heiligenverehrung im Islam", in Muh. Stud., ii, 275-378

- Grace Martin Smith and C.W. Ernst (eds.), Manifestations of sainthood in Islam, Istanbul 1993

- H.-Ch. Loir et Cl. Gilliot (eds.), Le culte des saints dans le monde musulman, Paris 1995.