Baroque painting

Baroque painting is the painting associated with the Baroque cultural movement. The movement is often identified with Absolutism, the Counter Reformation and Catholic Revival,[1][2] but the existence of important Baroque art and architecture in non-absolutist and Protestant states throughout Western Europe underscores its widespread popularity.[3]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Baroque painting encompasses a great range of styles, as most important and major painting during the period beginning around 1600 and continuing throughout the 17th century, and into the early 18th century is identified today as Baroque painting. In its most typical manifestations, Baroque art is characterized by great drama, rich, deep colour, and intense light and dark shadows, but the classicism of French Baroque painters like Poussin and Dutch genre painters such as Vermeer are also covered by the term, at least in English.[4] As opposed to Renaissance art, which usually showed the moment before an event took place, Baroque artists chose the most dramatic point, the moment when the action was occurring: Michelangelo, working in the High Renaissance, shows his David composed and still before he battles Goliath; Bernini's Baroque David is caught in the act of hurling the stone at the giant. Baroque art was meant to evoke emotion and passion instead of the calm rationality that had been prized during the Renaissance.

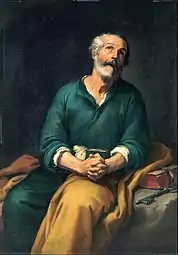

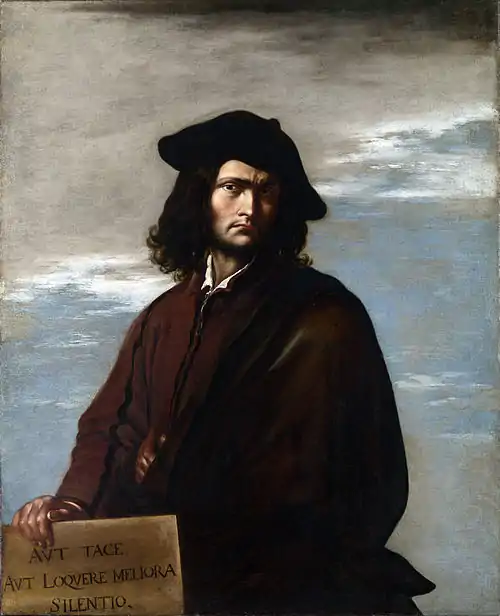

Among the greatest painters of the Baroque period are Velázquez, Caravaggio,[5] Rembrandt,[6] Rubens,[7] Poussin,[8] and Vermeer.[9] Caravaggio is an heir of the humanist painting of the High Renaissance. His realistic approach to the human figure, painted directly from life and dramatically spotlit against a dark background, shocked his contemporaries and opened a new chapter in the history of painting. Baroque painting often dramatizes scenes using chiaroscuro light effects; this can be seen in works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Le Nain and La Tour. The Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck developed a graceful but imposing portrait style that was very influential, especially in England.

The prosperity of 17th century Holland led to an enormous production of art by large numbers of painters who were mostly highly specialized and painted only genre scenes, landscapes, still lifes, portraits or history paintings. Technical standards were very high, and Dutch Golden Age painting established a new repertoire of subjects that was very influential until the arrival of Modernism.

History

The Council of Trent (1545–63), in which the Roman Catholic Church answered many questions of internal reform raised by both Protestants and by those who had remained inside the Catholic Church, addressed the representational arts in a short and somewhat oblique passage in its decrees. This was subsequently interpreted and expounded by a number of clerical authors like Molanus, who demanded that paintings and sculptures in church contexts should depict their subjects clearly and powerfully, and with decorum, without the stylistic airs of Mannerism. This return toward a populist conception of the function of ecclesiastical art is seen by many art historians as driving the innovations of Caravaggio and the Carracci brothers, all of whom were working (and competing for commissions) in Rome around 1600, although unlike the Carracci, Caravaggio persistently was criticised for lack of decorum in his work. However, although religious painting, history painting, allegories, and portraits were still considered the most noble subjects, landscape, still life, and genre scenes were also becoming more common in Catholic countries, and were the main genres in Protestant ones.

The term

The term "Baroque" was initially used with a derogatory meaning, to underline the excesses of its emphasis. Others derive it from the mnemonic term "Baroco" denoting, in logical Scholastica, a supposedly laboured form of syllogism.[10] In particular, the term was used to describe its eccentric redundancy and noisy abundance of details, which sharply contrasted the clear and sober rationality of the Renaissance. It was first rehabilitated by the Swiss-born art historian, Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) in his Renaissance und Barock (1888); Wölfflin identified the Baroque as "movement imported into mass", an art antithetic to Renaissance art. He did not make the distinctions between Mannerism and Baroque that modern writers do, and he ignored the later phase, the academic Baroque that lasted into the 18th century. Writers in French and English did not begin to treat Baroque as a respectable study until Wölfflin's influence had made German scholarship pre-eminent.

National variations

Led by Italy, Mediterranean countries, slowly followed by most of the Holy Roman Empire in Germany and Central Europe, generally adopted a full-blooded Baroque approach.

A rather different art developed out of northern realist traditions in 17th century Dutch Golden Age painting, which had very little religious art, and little history painting, instead playing a crucial part in developing secular genres such as still life, genre paintings of everyday scenes, and landscape painting. While the Baroque nature of Rembrandt's art is clear, the label is less used for Vermeer and many other Dutch artists. Most Dutch art lacks the idealization and love of splendour typical of much Baroque work, including the neighbouring Flemish Baroque painting which shared a part in Dutch trends, while also continuing to produce the traditional categories in a more clearly Baroque style.

In France a dignified and graceful classicism gave a distinctive flavour to Baroque painting, where the later 17th century is also regarded as a golden age for painting. Two of the most important artists, Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, remained based in Rome, where their work, almost all in easel paintings, was much appreciated by Italian as well as French patrons.

Baroque painters

British

- William Dobson (1611–1646)

- George Jamesone (1587–1644)

- Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723)

- Peter Lely (1618–1680)

- Daniël Mijtens (1590–1648)

- John Michael Wright (1617–1694)

Dutch

- Rembrandt (1606–1669)

- Hendrick Avercamp (1585–1634)

- Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681)

- Adriaen Brouwer (1605–1638)

- Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629)

- Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691)

- Gerrit Dou (1613–1675)

- Jan van Goyen (1596–1656)

- Frans Hals (1580–1666)

- Meindert Hobbema (1638–1709)

- Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656)

- Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684)

- Willem Kalf (1619–1693)

- Pieter van Laer (1599–1642)

- Judith Leyster (1609–1660)

- Gabriël Metsu (1629–1667)

- Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685)

- Jacob van Ruisdael (1628–1682)

- Salomon van Ruysdael (1602–1670)

- Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (1597–1665)

- Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675)

- Jan Steen (1626–1679)

Czech (Bohemian)

- Václav Hollar (1607–1677)

- Karel Škréta (1610–1674)

- Petr Brandl (1668–1735)

- Václav Vavřinec Reiner (1686–1743)

Flemish

- Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

- Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

- Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678)

- Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625)

- Frans Francken the Younger (1581–1642)

- Clara Peeters (1594–1657)

- Gerard Seghers (1591–1651)

- Frans Snyders (1579–1657)

- David Teniers the Younger (1610–1691)

- Adriaen van Utrecht (1599–1652)

- Cornelis de Vos (1584–1651)

French

- Valentin de Boulogne (1591–1632)

- Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674)

- Laurent de La Hyre (1606–1656)

- Georges de La Tour (1593–1652)

- Charles Le Brun (1619–1690)

- Le Nain brothers :

- Antoine Le Nain (c. 1599–1648)

- Louis Le Nain (c. 1593–1648)

- Mathieu Le Nain (1607–1677)

- Eustache Le Sueur (1617–1655)

- Claude Lorrain (1600–1682)

- Pierre Mignard (1612–1695)

- Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743)

- Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

- Simon Vouet (1590–1649)

German

- Cosmas Damian Asam (1686–1739)

- Wolfgang Heimbach (1605-1678)

- Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610)

- Johann Liss (1590–1627)

- Sebastian Stoskopff (1597–1657)

Hungarian

- Ádám Mányoki (1673–1757)

Italian

- Federico Barocci (1535–1612)

- Jacopo Chimenti (1554–1640)

- Giovanni Battista Paggi (1554–1627)

- Antonio Tempesta (1555–1630)

- Bartolomeo Cesi (1556–1629)

- Alessandro Maganza (1556–1640)

- Bernardo Castello (1557–1629)

- Lodovico Cigoli (1559–1613)

- Enea Talpino (1559–1626)

- Bartolommeo Carducci (1560–1610)

- Caravaggio (1571–1610)

- Guercino (1591–1666)

- Annibale Carracci (1560–1609)

- Guido Reni (1575–1642)

- Giuseppe Passeri (1654-1714)

- Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639)

- Artemisia Gentileschi (1592– c. 1656)

- Domenichino (1581–1641)

- Agostino Carracci (1557–1602)

- Ludovico Carracci (1555–1619)

- Bernardo Strozzi (1581-1644)

- Pietro da Cortona (1596–1669)

- Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670)

- Virginia Vezzi (1601-1638)

- Gregorio Preti (1603–1672)

- Francesco Cozza (1605–1682)

- Mattia Preti (1613–1699)

- Salvator Rosa (1615–1673)

- Luca Giordano (1634-1705)

- Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665)

- Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709)

Polish

- pl:Jan Reisner (1655–1713)

- Jerzy Siemiginowski-Eleuter (1660–1711)

- Szymon Czechowicz (1689–1775)

- Bartlomiej Strobel (1591–1650)

- Krzysztof Boguszewski (1635)

Portuguese

- Josefa de Óbidos (1630–1684)

Spanish

- José Antolínez (1635–1675)

- Alonso Cano (1601–1667)

- Juan Carreño de Miranda (1614–1685)

- Claudio Coello (1642–1693)

- Juan van der Hamen (1596–1631)

- Juan Bautista Maíno (1569–1649)

- Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (1612–1667)

- Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682)

- Antonio de Pereda (1611–1678)

- Lorenzo Quiros (1717 – 1789)

- Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644)

- Francisco Ribalta (1565–1628)

- José de Ribera, Lo Spagnoletto (1591–1652)

- Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–1690)

- Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

- Tomás Yepes (1595 or 1600 – 1674)

- Francisco Zurbarán (1598–1664)

Gallery

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, 1614–20, oil on canvas, 199 x 162 cm Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, 1614–20, oil on canvas, 199 x 162 cm Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Claude Lorrain, The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648, 149 × 194 cm., National Gallery, London

Claude Lorrain, The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648, 149 × 194 cm., National Gallery, London

_van_het_Amsterdamse_lakenbereidersgilde_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Rembrandt van Rijn, The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild, 1662, oil on canvas, 191.5 cm × 279 cm (75.4 in × 109.8 in), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild, 1662, oil on canvas, 191.5 cm × 279 cm (75.4 in × 109.8 in), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Jan Vermeer, The Allegory of Painting or The Art of Painting, 1666–67, 130 x 110 cm., Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Jan Vermeer, The Allegory of Painting or The Art of Painting, 1666–67, 130 x 110 cm., Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

References

- Counter Reformation, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online, latest edition, full-article.

- Counter Reformation Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine, from The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05.

- Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, "Gardner's Art Through the Ages" (Belmont, California: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2005)

- For example, in French calling Poussin Baroque would be generally rejected

- "Getty profile, including variant spellings of the artist's name". Getty.edu. 2002-12-11. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- Gombrich, p. 420.

- Belkin (1998): 11–18.

- His Lives of the Painters was published in Rome, 1672. Poussin's other contemporary biographer was André Félibien.

- W. Liedtke (2007) Dutch Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 867.

- Panofsky, Erwin (1995). "What is Baroque?". Three Essays on Style. The MIT Press: 19.

- Often described as Saint Bartholemew, martyred in similar fashion, but now recognized as St Philip. See Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 315, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, No ISBN.

Reading

- Belkin, Kristin Lohse (1998). Rubens. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3412-2.

- Belting, Hans (1994). Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Edmund Jephcott. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04215-4.

- Mark Getlein, Living With Art, 8th edition.

- Gombrich, E.H., The Story of Art, Phaidon, 1995. ISBN 0-7148-3355-X

- Christine Buci-Glucksmann, Baroque Reason: The Aesthetics of Modernity, Sage, 1994

- Michael Kitson, 1966. The Age of Baroque'

- Heinrich Wölfflin, 1964. Renaissance and Baroque (Reprinted 1984; originally published in German, 1888) The classic study. ISBN 0-8014-9046-4

.jpg.webp)