Battle of Albert (1916)

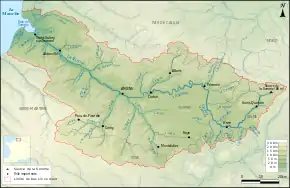

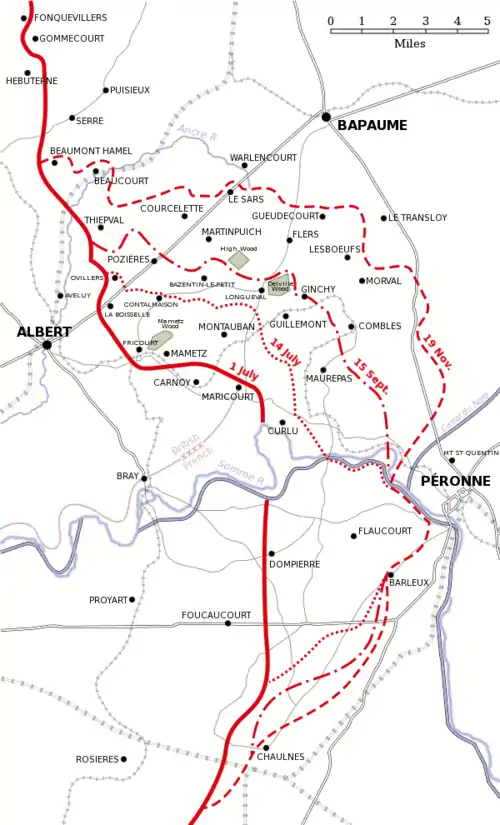

The Battle of Albert (1–13 July 1916) is the British name for the first two weeks of British–French offensive operations of the Battle of the Somme. The Allied preparatory artillery bombardment commenced on 24 June and the British–French infantry attacked on 1 July, on the south bank from Foucaucourt to the Somme and from the Somme north to Gommecourt, 2 mi (3.2 km) beyond Serre. The French Sixth Army and the right wing of the British Fourth Army inflicted a considerable defeat on the German 2nd Army but from near the Albert–Bapaume road to Gommecourt, the British attack was a disaster, where most of the c. 57,000 British casualties of the day were incurred. Against the wishes of General Joseph Joffre, General Sir Douglas Haig abandoned the offensive north of the road to reinforce the success in the south, where the British–French forces pressed forward through several intermediate lines closer to the German second position.

| Battle of Albert (1916) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Somme | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Joseph Joffre Douglas Haig Ferdinand Foch Henry Rawlinson Marie Émile Fayolle Hubert Gough Edmund Allenby |

Erich von Falkenhayn Fritz von Below Fritz von Loßberg Günther von Pannewitz | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

13 British divisions 11 French divisions | 6 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

British, 1 July: 57,470 2–13 July: 25,000 French, 1 July: 1,590 2–21 July: 17,600 |

1 July: 10,200 1–10 July: 40,187–46,315 | ||||||

The French Sixth Army advanced across the Flaucourt plateau south of the Somme and reached Flaucourt village by the evening of 3 July, taking Belloy-en-Santerre and Feullières on 4 July. The French also pierced the German third line opposite Péronne at La Maisonette and Biaches by the evening of 10 July. German reinforcements were then able to slow the French advance and defeat attacks on Barleux. On the north bank, XX Corps was ordered to consolidate the ground captured on 1 July, except for the completion of the advance to the first objective at Hem next to the river, which was captured on 5 July. Some minor attacks took place and German counter-attacks at Hem on 6 to 7 July nearly retook the village. A German attack at Bois Favières delayed a joint British–French attack from Hardecourt to Trônes Wood by 24 hours until 8 July.

British attacks south of the road between Albert and Bapaume began on 2 July, despite congested supply routes to the French XX Corps and the three British corps in the area. La Boisselle near the road was captured on 4 July, Bernafay and Caterpillar woods were occupied from 3 to 4 July and then fighting to capture Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison took place until early on 14 July, when the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July) began. German reinforcements reaching the Somme front were thrown into the defensive battle as soon as they arrived and had many casualties, as did the British attackers. Both sides were reduced to piecemeal operations, which were hurried, poorly organised and sent troops unfamiliar with the ground into action with inadequate reconnaissance. Attacks were poorly supported by artillery-fire, which was not adequately co-ordinated with the infantry and sometimes fired on ground occupied by friendly troops. Much criticism has been made of the British attacks as uncoordinated, tactically crude and wasteful of manpower, which gave the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their inferior resources on narrow fronts.

The loss of about 57,000 British casualties in one day was never repeated but from 2 to 13 July, the British had about 25,000 more casualties; the rate of loss changed from about 60,000 to 2,083 per day. From 1 to 10 July, the Germans had 40,187 casualties against a British total of about 85,000 from 1 to 13 July. The effect of the battle on the defenders has received less attention in English-language writing. The strain imposed by the British attacks after 1 July and the French advance on the south bank led General Fritz von Below to issue an order of the day on 3 July, forbidding voluntary withdrawals ("The enemy should have to carve his way over heaps of corpses.") after Falkenhayn had sacked Generalmajor Paul Grünert, the 2nd Army Chief of Staff and General der Infanterie Günther von Pannewitz, the commander of XVII Corps, for ordering the corps to withdraw to the third position close to Péronne. The German offensive at Verdun had already been reduced on 24 June to conserve manpower and ammunition; after the failure to capture Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn ordered a "strict defensive" and the transfer of more troops and artillery to the Somme front, which was the first strategic effect of the British–French offensive.

Background

Strategic developments

The Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, intended to split the British and French alliance in 1916 and end the war, before the Central Powers were crushed by Allied material superiority. To obtain decisive victory, Falkenhayn needed to find a way to break through the Western Front and defeat the strategic reserves which the Allies could move into the path of a breakthrough. Falkenhayn planned to provoke the French into attacking, by threatening a sensitive point close to the existing front line. Falkenhayn chose to attack towards Verdun over the Meuse Heights, to capture ground which overlooked Verdun to make it untenable. The French would have to conduct a counter-offensive, on ground dominated by the German army and ringed with masses of heavy artillery, inevitably leading to huge losses and bringing the French army close to collapse. The British would have no choice but to begin a hasty relief offensive, to divert German attention from Verdun but would also suffer huge losses. If these defeats were not enough, Germany would attack both armies and end the western alliance for good.[1]

The unexpected length and cost of the Verdun offensive and the underestimation of the need to replace exhausted units there, depleted the German strategic reserve placed behind the 6th Army, which held the front between Hannescamps 11 mi (18 km) south-west of Arras and St Eloi, south of Ypres and reduced the German counter-offensive strategy north of the Somme to one of passive and unyielding defence.[2] On the Eastern Front the Brusilov Offensive began on 4 June and on 7 June a German corps was sent to Russia from the western reserve, followed quickly by two more divisions.[3] After the failure to capture Fort Souville at Verdun on 12 July, Falkenhayn was obliged to suspend the offensive and reinforce the defences of the Somme front, even though the 5th Army was on the brink of the strategic objectives of the offensive.[4]

The British–French plan for an offensive on the Somme front had been decided at the Chantilly Conference of December 1915 as part of a general Allied offensive by the British, French, Italians and Russians. British–French intentions were quickly undermined by the German offensive at Verdun which began on 21 February 1916. The original proposal was for the British to conduct preparatory offensives in 1916 before a great British–French offensive from Lassigny to Gommecourt, in which the British would participate with all the forces they still had available. The French would attack with 39 divisions on a front of 30 mi (48 km) and the British with c. 25 divisions on 15 mi (24 km) on the northern French flank. The course of the battle at Verdun led the French gradually to reduce the number of divisions for operations on the Somme, until it became a supporting attack for the British on a 6 mi (9.7 km) front with only five divisions. The original intention had been for a rapid eastwards advance to the higher ground beyond the Somme and Tortille rivers, during which the British would occupy the ground beyond the upper Ancre. The combined armies would then attack south-east and north-east, to roll up the German defences on the flanks of the breakthrough.[5] By 1 July, the strategic ambition of the Somme offensive had been reduced in scope from a decisive blow against Germany, to relieving the pressure on the French army at Verdun and contributing, with the Russian and Italian armies, to the common Allied offensive.[6]

1 July

The First day on the Somme was the opening day of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July 1916). Nine corps of the French Sixth Army and the British Fourth and Third armies attacked the German 2nd Army (General Fritz von Below), from Foucaucourt south of the Somme to Serre, north of the Ancre and at Gommecourt 2 mi (3 km) beyond. The objective of the attack was to capture the German first and second positions from Serre south to the Albert–Bapaume road and the first position from the road south to Foucaucourt. Most of the German defences south of the road collapsed and the French attack succeeded on both banks of the Somme, as did the British from Maricourt on the army boundary, where XIII Corps took Montauban and reached all its objectives and XV Corps captured Mametz and isolated Fricourt.[7] The III Corps attack either side of the Albert–Bapaume road was a disaster, making a substantial advance next to the 21st Division on the right and only a short advance at Lochnagar Crater and to the south of La Boisselle; the largest number of casualties of the day was suffered by the 34th Division.[8] Further north, X Corps captured part of the Leipzig Redoubt, failed opposite Thiepval and had a great but temporary success on the left, where the 36th (Ulster) Division overran the German front line and captured temporarily the Schwaben and Stuff redoubts.[9]

German counter-attacks during the afternoon, recaptured most of the lost ground and fresh attacks against Thiepval were defeated, with more great loss to the British. On the north bank of the Ancre, the attack of VIII Corps was another disaster, with large numbers of British troops being shot down in no man's land. The diversionary Attack on the Gommecourt Salient by VII Corps was also costly, with only a partial and temporary advance south of the village.[10] The German defeats from Foucaucourt to the Albert–Bapaume road left the German defence south of the Somme incapable of resisting another attack and a substantial German retreat began from the Flaucourt plateau towards Péronne; north of the river, Fricourt was abandoned overnight.[11] The British army had suffered its highest number of casualties in a day and the elaborate defences built by the Germans over two years had collapsed from Foucaucourt south of the Somme, to the area just south of the Albert–Bapaume road north of the river, throwing the defence into a crisis and leaving the Poilus "buoyant".[12] A German counter-attack north of the Somme was ordered but took until 3:00 a.m. on 2 July to begin.[13]

2–13 July

It took until 4 July for the British to relieve the divisions shattered by the attack of 1 July and resume operations south of the Albert–Bapaume road. The number of German defenders in the area was underestimated but British Intelligence reports of a state of chaos in the German 2nd Army and piecemeal reinforcement of threatened areas, were accurate. The British changed tactics after 1 July and used the French method of smaller, shallower and artillery-laden attacks. Operations were conducted to advance south of the Albert–Bapaume road, towards the German second position, in time for a second general attack on 10 July, which due to the effect of the German defence and British–French supply difficulties in the Maricourt Salient, was postponed to 14 July.[14] German counter-attacks were as costly as British-French attacks and the loss of the most elaborately fortified German positions, like those at La Boisselle, prompted determined German efforts to recapture them. A combined British–French attack was planned for 7 July, postponed until 8 July after a German counter-attack at Bois Favière captured part of the wood. The inherent difficulties of coalition warfare were made worse by the German defensive effort and several downpours of rain, which turned the ground to mud and filled shell-holes with water, making movement difficult, even in areas not under fire.[15]

In the afternoon of 1 July, Falkenhayn arrived at the 2nd Army headquarters and found that part of the second line, south of the Somme, had been abandoned for a new shorter line. Falkenhayn sacked the Chief of Staff Major-General Paul Grünert and appointed Colonel Fritz von Loßberg, who extracted a promise from Falkenhayn to stop operations at Verdun and arrived on the Somme front at 5:00 a.m. on 2 July. Loßberg studied the battlefield from a hill north of Péronne then toured units, reiterating the ruling that no ground be abandoned regardless of the tactical situation. Loßberg and Below agreed that the defence should be conducted by a thin forward line, supported by immediate counter-attacks (Gegenstösse) which if unsuccessful, were to be followed by methodical counter-attacks (Gegenangriffe). A new telephone system was to be installed parallel to the battlefront beyond artillery range, with branches running forward to headquarters. A beginning was made on revising the artillery command organisation, by uniting divisional and heavy artillery headquarters in each divisional sector. Artillery-observation posts were withdrawn from the front line and placed several hundred yards/metres behind, where visibility was not as restricted by smoke and dust thrown about by shell-explosions. The flow of reinforcements was too slow to establish a line of reserve divisions behind the battlefront, a practice which had been a great success in the Herbstschlacht (Second Battle of Champagne September–October 1915). German reserves were sent into action in companies and battalions, as soon as they arrived, which disorganised formed units and reduced their effectiveness; many of the irreplaceable trained and experienced men were lost.[16]

Prelude

British–French preparations

| Date | Cylinders | Gas |

|---|---|---|

| 26/6 | 1,694 | White Star (phosgene– chlorine) |

| 27/6 | 5,190 | White Star |

| 28/6 | 3,487 | White Star & Red Star (chlorine) |

| 29/6 | 404 | White Star |

| 30/6 | 894 | White Star & Red Star |

| 1/7 | 676 | White Star & Red Star |

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), had received much more artillery by mid-1916 and had also expanded to eighteen corps.[18][lower-alpha 1] The 1,537 guns available to the British on the Somme, provided one field gun per 20 yd (18 m) of front and one heavy gun per 58 yd (53 m), to fire on 22,000 yd (13 mi; 20 km) of German front line trench and 300,000 yd (170 mi; 270 km) of support trenches.[19][lower-alpha 2] Each British corps on the Somme began to prepare artillery positions and infrastructure in March 1916, ready to receive artillery at the last moment to conceal as much as possible from German reconnaissance aircraft. Digging of trenches, dugouts and observation posts and building of roads railways and tramways began and new telephone lines and exchanges were installed. Each corps was informed of the amount of artillery, number of divisions, aircraft and labour battalions allotted. After the initial preparations, planning for the attack began on 7 March, which in the X Corps area was to be made by the 32nd Division and the 36th (Ulster) Division with the 49th (West Riding) Division in reserve.[22]

The Fourth Army artillery commander, produced the first "Army Artillery Operation Order", which laid down the tasks to be performed and delegated the details to the corps artillery commanders. In X Corps, a lifting barrage was planned and control of the artillery was not handed back to divisional commanders, because RFC and heavy artillery Forward Observation Officers (FOO) reported to the corps headquarters, which could expect to be better and quicker informed than divisions. Much discussion took place between the divisional and corps staffs and was repeated at meetings between the corps commanders and the Fourth Army commander, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, who on 21 April asked for plans to be submitted by each division within the corps framework.[22]

British planning for the battle introduced daily objectives, GHQ and the Fourth Army headquarters setting objectives and leaving to corps and divisional commanders, discretion about the means to achieve them. By June, each corps was liaising with neighbouring corps and divisions, divisions were asked to send in wire-cutting timetables, so that the heavy artillery (under corps command) could refrain from bombarding the same areas, reducing visibility needed to observe the effect of the divisional artillery. In VIII Corps, the plan ran to 70 pages with 28 headings, including details for infantry companies.[23][lower-alpha 3] Other corps made similar plans but went into less detail than VIII Corps, all conforming to the general instructions contained in the Fourth Army Tactical Notes. Planning in the Third Army for the attack on Gommecourt, showed a similar pattern of discussion and negotiation between divisions, corps and army headquarters. Lieutenant-General Thomas Snow, the VII Corps commander, made representations to the Third Army that Gommecourt was the wrong place for a diversion but was over-ruled, because the staff at GHQ considered the protection of the left flank of VIII Corps from artillery-fire from the north, to be more important.[24]

Preparations began on 3 July for an attack on the German second position between Longueval and Bazentin le Petit. Engineers and pioneers cleared roads and tracks, filled in old trenches and brought forward artillery and ammunition; the objective and the German third position were photographed from the air. All of the British infantry commanders wanted to attack at dawn, before German machine-gunners could see easily. A dawn attack needed a secret night assembly on the far side of no man's land, which was 1,200 yd (0.68 mi; 1.1 km) wide. Haig and Rawlinson discussed the plan several times, with Haig having severe doubts about the feasibility of a night-assembly and suggested an evening attack on the right flank, where no man's land was narrowest. Rawlinson and the corps commanders insisted on the original plan and eventually Haig gave way. A preliminary bombardment began on 11 July, with artillery-fire on the German positions to be attacked, counter-battery fire and night firing on villages and approaches behind the German front line, particularly Waterlot Farm, Flers, High Wood, Martinpuich, Le Sars and Bapaume. The Reserve Army bombarded Pozières and Courcelette and the French bombarded Waterlot Farm, Guillemont and Ginchy. Strict economy of ammunition was necessary, with heavy guns limited to 25–250 shells per day. British and French aircraft prevented German air observation and ammunition was moved forward night and day, over ground so damaged and waterlogged, that it took five or six hours to make a round-trip.[25]

British–French plans

Rawlinson submitted a plan to Haig on 3 April for an attack on a front of 20,000 yd (11 mi; 18 km), to a depth of 2,000–5,000 yd (1.1–2.8 mi; 1.8–4.6 km), between Maricourt and Serre. The plan contained the alternatives of an advance by stages or one rush and whether to attack after a hurricane bombardment or a methodical 48–72-hour bombardment. Rawlinson wanted to advance 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) and capture the German front position from Mametz to Serre and then after a pause, advance another 1,000 yd (910 m) from Fricourt to Serre, which included the German second position from Pozières to Grandcourt. Haig called the plan a proposal for a frontal advance of equal strength along all the front. Haig directed Rawlinson to consider advancing beyond the first position, near Montauban on the right and at Miraumont and Serre on the left but offered no extra forces to achieve this.[26]

Haig suggested that with the ample artillery ammunition available, capturing the Montauban spur would be easier on the first day and that and the tactical benefit of possession of the Montauban and Serre–Miraumont spurs would reduce the danger from German counter-attacks. After consultations between Joffre, General Ferdinand Foch and Haig, Rawlinson was instructed to plan for an advance of 1.5 mi (2.4 km) on a 25,000 yd (14 mi; 23 km) front, taking the German first position and advancing midway to the second position on the right at Montauban, taking the first position in the centre and the second position from Pozières to Grandcourt. An extra corps was allotted to the Fourth Army but the different concepts of step by step advances or a quicker advance to force German withdrawals on the flanks, was not resolved. Further problems arose when the French contribution to the offensive was reduced and in late May, the British began to doubt that the French could participate at all.[27] On 29 May, Haig directed that the aims of the offensive would be to wear down the German army and reach positions favourable for an offensive in 1917.[26]

The British–French attacks on 1 July had succeeded on the southern half of the front but north of the Albert–Bapaume road the British had advanced to disaster, with little ground taken and most of the c. 57,000 Fourth Army casualties suffered. The extent of the British losses was not known on the evening of 1 July but Haig wanted the attack to continue, to further the intent of inflicting casualties on the Germans and to reach a line from which the German second position could be attacked. At 10:00 p.m. Rawlinson ordered the offensive to continue, with XIII Corps and XV Corps to occupy Mametz Wood on their right and capture Fricourt on the left; III Corps to take La Boisselle and Ovillers and for X Corps and VIII Corps to take the German front trenches and an intermediate line. The main effort was still to be in the north, because congestion behind the front between the Somme and Maricourt made it impossible quickly to resume the attack on the junction of the British and French armies. Lieutenant-General Sir Hubert Gough was sent from the Reserve Army to command X Corps and VIII Corps for the renewed attack north of the Albert–Bapaume road and several of the divisions shattered on 1 July were relieved.[28] Haig met Rawlinson on 2 July to discuss the effect that the shortage of ammunition would have on operations and how to approach the German second position from Longueval to Bazentin le Petit and outflank the German defences north of the Albert–Bapaume road.[lower-alpha 4] Attacks north of the road were to be made at 3:15 a.m. on 3 July and arrangements were to be made with Foch to improve communications north of the Somme. Later in the day, Haig urged Rawlinson to attack on the right flank and reduced the attack north of the Albert–Bapaume road to an attack by two brigades.[30]

Foch met Rawlinson on 3 July and then, with Joffre, met Haig during the afternoon, at which the French objected to the shifting of the weight of the British offensive to the right flank. Haig pointed out that there was insufficient artillery ammunition to resume the attack in the north and after a "full and frank exchange of views", Joffre acquiesced. The British would end the offensive north of the Ancre and concentrate on the area between Montauban and Fricourt and then attack the German second position between Loguelval and Bazentin le Petit. Joffre gave Foch responsibility for co-ordinating the French effort with the British.[31] Foch arranged for the French Sixth Army to continue the offensive south of the river and to bring two more corps into the XX Corps area on the north bank to advance to the Péronne–Bapaume road to outflank the German defences along the river, dismounted cavalry linking the attacks on either side of the river.[32] That night the Fourth Army staff ordered that preparations be made for an attack on the German second position from Longueval to Bazentin le Petit, by advancing to attacking distance through Bernafay and Caterpillar woods, Mametz Wood, Contalmaison and north of La Boisselle. The Reserve Army was to pin the German garrisons to its front and X Corps was to expand its footholds on the German front line.[33]

Haig met Rawlinson again on 4 July and laid down that Trônes Wood, on the boundary with the French XX Corps, with Contalmaison and Mametz Wood on the left flank, must be captured to cover the flanks of the attack on the German second position, then visited the corps commanders to emphasise the urgency of these attacks. Foch informed Rawlinson that the French would attack at Hardecourt, together with British attacks on Trônes Wood and Maltz Horn Farm.[34] On 5 July, Haig met Rawlinson and Gough to arrange the preparatory attacks and to allot daily ammunition rations, most of which went to the Fourth Army. Next day Rawlinson met Fayolle to co-ordinate the attacks on Hardecourt and Trônes Wood due on 7 July, which was then postponed to 8 July after a German counter-attack on Bois Favière.[35] On 6 July, BEF headquarters laid down a policy that British numerical superiority was to be used to exploit German disorganisation and diminished morale, by boldly following up the success south of the Albert–Bapaume road. BEF Military Intelligence estimated that there were only fifteen German battalions between Hardecourt and La Boisselle, eleven having suffered severe losses.[lower-alpha 5] More fresh divisions were sent to the Somme front, where all of the divisions in the area had been engaged, only the 8th Division having been transferred elsewhere.[36]

On 7 July, Haig told Gough quickly to capture Ovillers and link with III Corps at La Boisselle; later on he ordered the I ANZAC Corps and the 33rd Division into the Fourth Army area, sent the 36th (Ulster) Division to Flanders and moved the 51st (Highland) Division into reserve; these changes began a process of reliefs on the Somme front, which continued until the end of the battle in November. Late on 8 July, after a meeting with Haig, at which several sackings of senior commanders were agreed, Rawlinson and the Fourth Army corps commanders met to discuss the forthcoming operation to capture the German second position from Longueval to Bazentin le Petit. The operation order was issued for an attack possibly at 8:00 a.m. on 10 July but the date was left open until the effect of the preliminary operations and the weather were known. Hard and costly fighting did not secure all the objectives and it was not until 12 July that the time of the attack on the second position was fixed at 3:20 a.m. on 14 July, with the capture of Trônes Wood to be completed before midnight on 13/14 July, "at all costs".[37]

German preparations

| Date | Rain mm |

(°F) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| June | |||

| 23 | 2.0 | 79°–55° | wind |

| 24 | 1.0 | 72°–52° | dull |

| 25 | 1.0 | 71°–54° | wind |

| 26 | 6.0 | 72°–52° | cloud |

| 27 | 8.0 | 68°–54° | cloud |

| 28 | 2.0 | 68°–50° | dull |

| 29 | 0.1 | 66°–52° | cloud wind |

| 30 | 0.0 | 72°–48° | dull high wind |

| July | |||

| 1 | 0.0 | 79°–52° | fine |

Despite considerable debate among German staff officers, Falkenhayn laid down a continuation of the policy of unyielding defence.[39][lower-alpha 6] On the Somme front, the construction plan ordered by Falkenhayn in January 1915 had been completed. Barbed wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yd (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two, 30 yd (27 m) wide and about 15 yd (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) high. The front line had been increased from one line to three, 150–200 yd (140–180 m) apart, the first trench (Kampfgraben) occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) for the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yd (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strong points (Stützpunktlinie) about 1,000 yd (910 m) behind the front line had also been built.[41]

Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second line, which was as well built and wired as the first line. The second line was built beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the line.[41] After the Herbstschlacht (Autumn Battle) in Champagne during late 1915, a third line another 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) back from the Stützpunktlinie was begun in February 1916 and was nearly complete when the battle began.[41] On 12 May, the 2nd Guard Reserve Division was moved out of reserve, to defend Serre and Gommecourt, which reduced the frontage of the XIV Reserve Corps and its six divisions from 30,000–18,000 yd (17–10 mi; 27–16 km) between Maricourt and Serre, making the average divisional sector north of the Albert–Bapaume road 3.75 mi (6.04 km) wide, while the frontages south of the road were 4.5 mi (7.2 km) wide.[42]

German artillery was organised in a series of Sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors); each infantry officer was expected to know the batteries covering his section of the front line and the batteries ready to engage fleeting targets. A telephone system was built, with lines buried 6 ft (1.8 m) deep for 5 mi (8.0 km) behind the front line, to connect the front line to the artillery. The Somme defences had two inherent weaknesses which the rebuilding had not remedied. The front trenches were on a forward slope, lined by white chalk from the subsoil and easily seen by ground observers. The defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stützpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) of the front line.[43]

Most of the troops were within 1,000 yd (910 m) of the front line, accommodated in the new deep dugouts. The concentration of troops in the front line on a forward slope, guaranteed that it would face the bulk of an artillery bombardment, directed by ground observers on clearly marked lines.[43] The Germans had 598 field guns and howitzers and 246 heavy guns and howitzers, for the simpler task of placing barrages on no man's land. Telephone lines between the German front lines and their artillery support were cut but the front line troops used signal flares to communicate with the artillery. In many places, particularly north of the Albert–Bapaume road, German barrage-fire prevented British reinforcements from crossing no man's land and parties which had captured German positions, were isolated and cut off or forced to retire.[44]

Battle

French Sixth Army

By the end of 1 July, the Sixth Army had captured all of the German first position except Frise on the Somme Canal. Few casualties had been suffered and 4,000 prisoners had been taken. On the south bank, territorial troops buried the dead and cleared the battlefield of unexploded ammunition, as artillery was moved forward to prepared positions.[45] I Colonial Corps had advanced within attacking distance of the German second position and indications that the Germans were withdrawing artillery had been detected.[36] In 48 hours, the French had broken through on an 5.0 mi (8 km) front.[46] The advance of I Colonial Corps created a salient and German artillery, safe on the east bank of the Somme and assisted by more aircraft and observation balloons, could enfilade the defences hurriedly built by French troops and make movement on the Flaucourt Plateau impossible in daylight. German counter-attacks at Belloy, La Maisonette and Biaches, increased French casualties. A bold suggestion for a French attack northwards across the river was rejected.[47] By 6 July, Foch had decided to attack on both banks and to extend the attack with the Tenth Army, on the right of the Sixth Army, to exploit success on any part of the front.[48]

XXXV Corps

Estrées was captured in the evening, then a German counter-attack in the early hours, retook half of the village before the French attacked again late on 5 July and took back most of the village. An attack on Barleux failed and supply shortages emerged, as guns and equipment were moved forward, clogging roads.[49] Attacks to cross the Amiens–Vermand road towards Villers Carbonnel, after Barleux and Biaches were captured, began on 10 July, near Estrées but were repulsed.[50]

I Colonial Corps

Artillery began a systematic bombardment of the German second position, Frise was captured and the second position attacked at 4:30 p.m. and broken into at Herbécourt, where the French surrounded the village. The attack was repulsed at Assevillers, with the help of artillery-fire from the south. Next day, Assevillers was captured at 9:00 a.m. and air reconnaissance reported that no Germans were to be seen. Flaucourt and Feuillères were occupied at midday with 100 prisoners taken, the total having risen to 5,000 in two days. The German artillery around Flaucourt was abandoned and French cavalry probed towards the river, a total advance of 4.3 mi (7 km), the deepest penetration since trench warfare began.[51]

The 2nd Colonial Division (General Emile-Alexis Mazillier) advanced beyond Feuillères and occupied ground overlooking the boucle, (loop) formed by the sharp turn north-west of the Somme at Péronne.[48] The new French positions faced Maisonette on the right and Biaches to the front, along the southern length of the German third position, with Péronne visible across the river. Barleux and Biaches were captured on 4 July, by Foreign Legion troops of the Moroccan Division; in the afternoon counter-attacks from the north-east began and went on all night.[52]

The 72nd Division took over the line next to the south bank of the Somme overnight, the 16th Colonial Division relieved the 2nd Colonial Division near Biaches and the Moroccan Division relieved the 3rd Colonial Division. A preliminary attack on Barleux and Biaches was postponed from 8 to 9 July, because of bad weather after a thirty-hour bombardment and failed to capture Barleux, though the French broke through the German second position to capture Biaches. The 16th Colonial Division attacked La Maisonette at 2:00 p.m. from the south and occupied the village by 3:15 p.m.; an attack from the north being stopped by machine-gun fire from Bois Blaise. A German counter-attack behind a party of troops feigning surrender retook the orchard and Château, until another French attack pushed them out. Next morning, a German attack from five directions was repulsed.[53][lower-alpha 7] Bois Blaise was taken on 10 July and an attack on Barleux, was stopped by German machine-gunners hidden in crops around the village.[50]

XX Corps

Congestion in the Maricourt salient caused delays, in the carrying of supplies to British and French troops and at 8:30 p.m., an attack on Hardecourt and the intermediate line was postponed, until British troops attacked Bernafay and Trônes woods; at 10:30 a.m. XX Corps was ordered to stand fast.[36] The 11th Division lost twenty casualties on 3 July.[46] Hem and high ground to the north, behind defences 1,600 yd (1,500 m) deep back to Monacu Farm, were attacked by the 11th Division, which had been organised to advance in depth, with moppers-up wearing markings to distinguish their role. Communication with the artillery was crucial quickly to re-bombard areas, as the village was outflanked to the north and the ground consolidated. XX Corps artillery and guns on the south bank, bombarded the village for 48 hours and at 6:58 a.m. on 5 July, the infantry edged forward from saps (that had been dug under cover of a fog) and followed a creeping bombardment into the village, reaching the objectives in the north by 8:15 a.m. Hem was re-bombarded and attacked at midday, the village eventually being cleared at 5:00 p.m. and Bois Fromage was captured, after another bombardment at 6:30 p.m. Five German counter-attacks from 6 to 7 July around Bois Fromage, de l'Observatoire and Sommet, which changed hands four times, threatened the new French line with collapse, until a reserve company repulsed the foremost German troops in a grenade fight.[54]

Due to a lack of roads, Foch was not able to supply enough reinforcements on the north bank for an advance towards Maurepas, until British troops had captured the German second position from Longueval to Bazentin le Petit and were poised to attack Guillemont; XX Corps was ordered conduct counter-battery fire in the meantime.[55] A French attack on Favière Wood at 6:00 a.m. captured the north end briefly, before being pushed back by a counter-attack. Further attempts to capture the wood at 12:30 p.m. and 2:30 p.m. also failed.[55] The failure of British attacks from 7 to 8 July, led Foch to keep XX Corps stationary, until Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison were captured. The 39th Division attacked towards Hardecourt on 8 July, after a 24-hour postponement, caused by a German counter-attack at Bois Favière. The German defence was subjected to a "crushing bombardment" and the village swiftly captured, as the British 30th Division attacked Trônes Wood. The 39th Division was not able to advance further against machine-gun fire from the wood, after a German counter-attack forced back the British 30th Division.[56]

La Boisselle

| Date | Rain mm |

(°F) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| July | |||

| 1 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | fine hazy |

| 2 | 0.0 | 75°–54° | fine |

| 3 | 2.0 | 68°–55° | fine |

| 4 | 17.0 | 70°–55° | storm |

| 5 | 0.0 | 72–52° | low cloud |

| 6 | 2.0 | 70°–54° | rain |

| 7 | 13.0 | 70°–59° | rain |

| 8 | 8.0 | 73°–52° | rain |

| 9 | 0.0 | 70°–53° | dull |

| 10 | 0.0 | 82°–48° | |

| 11 | 0.0 | 68°–52° | dull |

| 12 | 0.1 | 68°–? | dull |

| 13 | 0.1 | 70°–54° | dull |

| 14 | 0.0 | 70°–? | dull |

The 19th (Western) Division brought forward a second brigade and at 2:15 a.m. on 3 July, a battalion and some specialist bombers attacked between La Boisselle and the Albert–Bapaume road, with a second battalion attacking from the southern flank at 3:15 a.m. In hand-to-hand fighting with troops of Reserve Infantry Regiment 23 of the 12th Reserve Division and Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 of the 28th Reserve Division, 123 prisoners were taken and the village was occupied. Red rockets had been fired by the German defenders and a bombardment by artillery and mortars was fired on the village before Infantry Regiment 190 of the 185th Division counter-attacked from Pozières and recaptured the east end of the village. British reinforcements from two more battalions arrived and eventually managed to advance 100 yd (91 m) from the original start line, to gain touch with the 12th (Eastern) Division, which dug a trench to the left flank of the 19th (Western) Division after dark.[58]

On the right flank, the 34th Division made three attempts to bomb its way to the right flank of the 19th (Western) Division, all of which failed and after dark began to hand over to the 23rd Division. The 34th Division had suffered 6,811 casualties from 1 to 5 July, which left the 102nd and 103rd brigades "shattered".[58] Rain fell overnight and heavy showers on 4 July lasted all afternoon, flooding trenches and grounding RFC aircraft, apart from a few flights to reconnoitre Mametz Wood.[59] At 8:30 a.m., a brigade of the 19th (Western) Division attacked towards La Boisselle against determined resistance from the garrison, reaching the east end at 2:30 p.m. in a thunderstorm.[59] The 19th (Western) Division attacked again at 8:15 a.m. on 7 July to capture trenches from near Bailiff Wood 600 yd (550 m) away, to 300 yd (270 m) beyond La Boisselle. Two battalions advanced as close as possible to the bombardment before it lifted and managed to run into it, before reorganising and resuming the advance with a third battalion, taking the objective and 400 prisoners.[60]

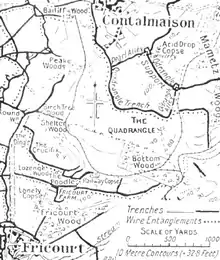

Contalmaison

Three battalions of the 17th (Northern) Division and 38th (Welsh) Division attacked towards Quadrangle Support Trench, part of Pearl Alley south of Mametz Wood and Contalmaison on 7 July, at 2:00 a.m. after a brief bombardment. The Germans were alert and a counter-barrage began promptly; many British shells fell short on the leading British troops, who found the wire uncut and fell back, eventually returning to their start-line. Part of the left-hand battalion got into Pearl Alley and some found themselves in Contalmaison before being driven back by part of Infantry Regiment Lehr and Grenadier Regiment 9 from the fresh 3rd Guard Division, which had been able to take over from Mametz Wood to Ovillers. The Germans tried to extend their counter-attacks from the east of Contalmaison towards the advanced positions of the 17th (Northern) Division, which were eventually repulsed at about 7:00 a.m. The troops, who had been delayed as they moved up to the start-line, advanced far behind the creeping barrage and were hit by machine-gun fire from Mametz Wood; the survivors were ordered back, apart from a few in advanced posts. On the right, part of the 50th Brigade had tried to bomb up Quadrangle Alley but was driven back.[61]

In the III Corps area on the left flank, the 68th Brigade of the 23rd Division was delayed by the barrage on Bailiff Wood until 9:15 a.m., when a battalion reached the southern fringe before machine-gun fire from Contalmaison forced them back 400 yd (370 m), as a fresh battalion worked along a trench towards the 19th (Western) Division on the left flank. The attack on Contalmaison by the 24th Brigade was to have begun when the 17th (Northern) Division attacked again on the right but mud and communication delays led to the attack not starting until after 10:00 a.m., when two battalions attacked from Pearl Alley and Shelter Wood. Contalmaison was entered and occupied up to the church after a thirty-minute fight, in which several counter-attacks were repulsed. The attack from Shelter Wood failed because the troops were slowed by mud and caught by machine-gun fire from Contalmaison and Bailiff Wood; the battalion in the village withdrew later in the afternoon.[62]

An attempt to attack again was cancelled due to the mud, a heavy German barrage and lack of fresh troops. The 68th Brigade dug in on the west, facing Contalmaison and the 14th Brigade dug in on the south side.[62] The 23rd Division attacked again to close a 400 yd (370 m) gap between the 24th and 68th brigades but the troops got stuck in mud so deep that they became trapped. Later in the day, the 24th Brigade attacked Contalmaison but was defeated by machine-gun fire and an artillery barrage. On the left, bombers of the 19th (Western) Division skirmished all day and at 6:00 p.m., a warning from an observer in a reconnaissance aircraft led to the ambush of German troops advancing towards Bailiff Wood who were stopped by small-arms fire. An advance on the left flank, in support of a 12th Division attack on Ovillers, got forward about 1,000 yd (910 m) and reached the north end of Ovillers.[63]

On 9 July, two brigades of the 23rd Division spent the morning attacking south and west of Contalmaison. A battalion of the 24th Brigade established a machine-gun nest in a commanding position south of the village and part of the 68th Brigade entered Bailiff Wood, before being shelled out by British artillery. An attempt to return later that day was forestalled by a German counter-attack by parts of II Battalion and III Battalion, Infantry Regiment 183 of the 183rd Division at 4:30 p.m. The attack was to reinforce the line between Contalmaison and Pozières but was repulsed with many casualties. The British attack began at 8:15 a.m. on 10 July, managed to occupy Bailiff Wood and trenches either side and at 4:30 p.m. after a careful reconnaissance, two battalions assembled along Horseshoe Trench, in a line 1,000 yd (910 m) long facing Contalmaison, 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) away to the east.[64]

Two companies were sent towards Bailiff Wood to attack the north end of the village. After a thirty-minute bombardment, a creeping barrage moved in five short lifts through the village to the eastern fringe as every machine-gun in the division fired on the edges of the village and the approaches. The attack moved forward in four waves, with mopping-up parties following, through much return fire from the garrison and reached a trench at the edge of the village, forcing the survivors to retreat into Contalmaison. The waves broke up into groups which advanced faster than the barrage; the divisional artillery commander accelerated the creeping barrage and the village was captured, despite determined opposition from parts of the garrison.[64]

The flank attack on the north end also reached its objective, met the main attacking force at 5:30 p.m. and sniped at the Germans as they retreated towards the second position; only c. 100 troops of the I Battalion, Grenadier Regiment 9 made it back. The village was consolidated inside a "box barrage" maintained all night and a large counter-attack was repulsed at 9:00 p.m. By noon on 11 July, the 23rd Division was relieved by the 1st Division, having suffered 3,485 casualties up to 10 July.[64] The German positions between Mametz Wood and Contalmaison, were finally captured by the 17th (Northern) Division, after they were outflanked by the capture of the village and the southern part of the wood, although bombing attacks up trenches on 9 July had failed. At 11:20 p.m., a surprise bayonet charge was attempted by a battalion each from the 50th and 51st brigades, which reached part of Quadrangle Support Trench on the left but eventually failed with many casualties. After the capture of Contalmaison next day, an afternoon attack by part of the 51st Brigade from the sunken road east of the village reached Quadrangle Support Trench. Parties of the 50th Brigade attacked westwards up Strip Trench and Wood Support Trench, against German defenders who fought hand-to-hand, at great cost to both sides, before the objective was captured. Touch was gained with the 38th (Welsh) Division in the wood and the 23rd Division in the village, before the 21st Division took over early on 11 July; the 17th (Northern) Division had suffered 4,771 casualties since 1 July.[65]

Mametz Wood

At 9:00 a.m. on 3 July, XV Corps advanced north from Fricourt and the 17th (Northern) Division reached Railway Alley, after a delay caused by German machine-gun fire at 11:30 a.m. A company advanced into Bottom Wood and was nearly surrounded, until troops from the 21st Division captured Shelter Wood on the left; German resistance collapsed and troops from the 17th (Northern) Division and 7th Division occupied Bottom Wood unopposed. Two field artillery batteries were brought up and began wire cutting around Mametz Wood; the 51st Brigade of the 7th Division, having lost about 500 casualties by then. In the 21st Division area on the boundary with III Corps to the north, a battalion of the 62nd Brigade advanced to Shelter Wood and Birch Tree Wood to the north-west, where many German troops emerged from dugouts and made bombing attacks, which slowed the British occupation of Shelter Wood. German troops were seen by observers in reconnaissance aircraft, advancing from Contalmaison at 11:30 a.m. and the British infantry attempted to envelop them, by an advance covered by Stokes mortars, which quickly captured Shelter Wood. The British repulsed a counter-attack at 2:00 p.m. with Lewis-gun fire and took almost 800 prisoners from Infantry Regiment 186 of the 185th Division, Infantry Regiment 23 of the 12th Division and Reserve Infantry Regiments 109, 110 and 111 of the 28th Reserve Division. The 63rd Brigade formed a defensive flank, until touch was gained with the 34th Division at Round Wood.[66]

The 7th, 17th (Northern) and 21st divisions of XV Corps began to consolidate on 3 July and many reports were sent back that the Germans were still disorganised, with Mametz Wood and Quadrangle Trench empty. At 5:00 p.m., the 7th Division was ordered to advance after dark, to the southern fringe of Mametz Wood but the guide got lost, which delayed the move until dawn. Next day the 17th (Northern) Division managed to bomb a short distance northwards, along trenches towards Contalmaison.[59] At midnight, a surprise advance by XV Corps to capture the south end of Mametz Wood, Wood Trench and Quadrangle Trench, was delayed by a rainstorm but began at 12:45 a.m. The leading troops crept to within 100 yd (91 m) of the German defences before zero hour and rushed the defenders, to capture Quadrangle Trench and Shelter Alley. On the right, the attackers were stopped by uncut wire and a counter-attack; several attempts to renew the advance were repulsed by German machine-gun fire at Mametz Wood and Wood Trench. The 38th (Welsh) Division relieved the 7th Division, which had lost 3,824 casualties since 1 July.[67] On the left, the 23rd Division of III Corps attacked as a flank support and took part of Horseshoe Trench, until forced out by a counter-attack at 10:00 a.m. At 6:00 p.m. another attack over the open, took Horseshoe Trench and Lincoln Redoubt; ground was gained to the east but contact with the 17th (Northern) Division was not gained at Shelter Alley.[68]

British artillery bombarded the attack front during the afternoon of 6 July and increased the bombardment to intense fire at 7:20 a.m. but heavy rain and communication difficulties on 7 July, led to several postponements of the attack by the 38th (Welsh) Division and the 17th (Northern) Division until 8:00 p.m. A preliminary attack on Quadrangle Support Trench, by two battalions of the 52nd Brigade took place at 5:25 a.m. The British barrage lifted before the troops were close enough to attack and they were cut down by machine-gun fire from Mametz Wood. On the right, a battalion of the 50th Brigade tried to bomb up Quadrangle Alley but was repulsed, as was an attack by a company which tried to advance towards the west side of Mametz Wood, against machine-gun fire from Strip Trench. The 115th Brigade of the 38th (Welsh) Division was too late to be covered by the preliminary bombardment and the attack was cancelled. The 38th (Welsh) Division attack on Mametz Wood began at 8:30 a.m., as a brigade advanced from Marlboro' Wood and Caterpillar Wood, supported by a trench mortar and machine-gun bombardment. Return fire stopped this attack and those at 10:15 a.m. and 3:15 p.m., when the attackers were stopped 250 yd (230 m) from the wood. The 17th (Northern) Division attacked next day from Quadrangle Trench and Pearl Alley at 6:00 a.m. in knee-deep mud but had made little progress by 10:00 a.m. Two battalions attacked again at 5:50 p.m. with little success but at 8:50 p.m., a company took most of Wood Trench unopposed and the 38th (Welsh) Division prepared a night attack on Mametz Wood but the platoon making the attack was not able to reach the start line before dawn.[61][lower-alpha 8]

The failure of the 38th (Welsh) Division to attack overnight, got the divisional commander Major-General Philipps sacked and replaced by Major-General Watts of the 7th Division on 9 July, who ordered an attack for 4:15 a.m. on 10 July, by all of the 38th (Welsh) Division. The attack was to commence after a forty-five-minute bombardment, with smoke-screens along the front of attack and a creeping bombardment by the 7th and 38th divisional artilleries, to move forward at zero hour at 50 yd (46 m) per minute until 6:15 a.m., when it would begin to move towards the second objective. The attacking battalions advanced from White Trench, the 114th Brigade on the right with two battalions and two in support, the 113th Brigade on the left with one battalion and a second in support, either side of a ride up the middle of the wood. The attack required an advance of 1,000 yd (910 m) down into Caterpillar valley and then uphill for 400 yd (370 m), to the southern fringe of the wood. The waves of infantry were engaged by massed small-arms fire from II Battalion, Infantry Regiment Lehr and III Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 122, which destroyed the attack formation, from which small groups of survivors continued the advance. The 114th Brigade reached the wood quickly behind the barrage and dug in at the first objective. Further west, the battalion of the 113th Brigade lost the barrage but managed to reach the first objective, despite crossfire and shelling by British guns. Various German parties surrendered and despite the chaos, it appeared that the German defence of the wood had collapsed. The artillery schedule could not be changed at such short notice and the German defence had two hours to recover. The advance to the second objective at 6:15 a.m. was delayed and conditions in the wood made it difficult to keep up with the barrage; an attack on an area called Hammerhead was forced back by a German counter-attack.[73]

On the left flank, fire from Quadrangle Alley stopped the advance and contact with the rear was lost, amidst the tangle of undergrowth and fallen trees. The barrage was eventually brought back and two battalions of the 115th Brigade were sent forward as reinforcements. The Hammerhead fell after a Stokes mortar bombardment and a German battalion headquarters was captured around 2:30 p.m., after which the German defence began to collapse. More British reinforcements arrived and attacks by the 50th Brigade of the 17th (Northern) Division on the left flank, helped capture Wood Support Trench. The advance resumed at 4:30 p.m. and after two hours, reached the northern fringe of the wood. Attempts to advance further were stopped by machine-gun fire and a defensive line 200 yd (180 m) inside the wood was dug. A resumption of the attack in the evening was cancelled and a withdrawal further into the wood saved the infantry from a German bombardment along the edge of the wood. In the early hours of 11 July, the 115th Brigade relieved the attacking brigades and at 3:30 p.m. a position was consolidated 60 yd (55 m) inside the wood but then abandoned due to German artillery-fire. The 38th (Welsh) Division was relieved by a brigade of the 12th Division by 9:00 a.m. on 12 July, which searched the wood and completed its occupation, the German defence having lost "countless brave men"; the 38th (Welsh) Division had lost c. 4,000 casualties. The northern fringe was reoccupied and linked with the 7th Division on the right and the 1st Division on the left, under constant bombardment by shrapnel, lachrymatory, high explosive and gas shell, the 62nd Brigade losing 950 men by 16 July.[74]

Trônes Wood

At 9:00 p.m. on 3 July, the 30th Division occupied Bernafay Wood, losing only six casualties and capturing seventeen prisoners, three field guns and three machine-guns. Patrols moved eastwards, discovered that Trônes Wood was defended by machine-gun detachments and withdrew. Caterpillar Wood was occupied by the 18th (Eastern) Division early on 4 July and reports from the advanced troops of the divisions of XIII Corps and XV Corps, indicated that they were pursuing a beaten enemy.[75] On the night of 4 July, the 18th (Eastern) Division took Marlboro' Wood unopposed but a combined attack by XX Corps and XIII Corps on 7 July, was postponed for 24 hours, after a German counter-attack on Favières Wood in the French area.[76] The British attack began on 8 July at 8:00 a.m., when a battalion advanced eastwards from Bernafay Wood and reached a small rise, where fire from German machine-guns and two field guns, caused many losses and stopped the advance, except for a bombing attack along Trônes Alley. A charge across the open was made by the survivors, who reached the wood and disappeared. The French 39th Division attacked at 10:05 a.m. and took the south end of Maltz Horn Trench, as a battalion of the 30th Division attacked from La Briqueterie and took the north end. A second attack from Bernafay Wood at 1:00 p.m., reached the south-eastern edge of Trônes Wood, despite many losses and dug in facing north. The 30th Division attacked again at 3:00 a.m. on 9 July, after a forty-minute bombardment. The 90th Brigade on the right advanced from La Briqueterie up a sunken road, rushed Maltz Horn Farm and then bombed up Maltz Horn Trench, to the Guillemont track.[76]

An attack from Bernafay Wood intended for the same time, was delayed after the battalion lost direction in the rain and a gas bombardment and did not advance from the wood until 6:00 a.m. The move into Trônes Wood was nearly unopposed, the battalion reached the eastern fringe at 8:00 a.m. and sent patrols northwards. A German heavy artillery bombardment began at 12:30 p.m., on an arc from Maurepas to Bazentin le Grand and as a counter-attack loomed, the British withdrew at 3:00 p.m. to Bernafay Wood. The German counter-attack by the II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 182 from the fresh 123rd Division and parts of Reserve Infantry Regiment 38 and Reserve Infantry Regiment 51, was pressed from Maltz Horn Farm to the north end of the wood and reached the wood north of the Guillemont track. A British advance north from La Briqueterie at 6:40 p.m., reached the south end of the wood and dug in 60 yd (55 m) from the south-western edge. Patrols northwards into the wood, found few Germans but had great difficulty in moving through undergrowth and fallen trees. At 4:00 a.m. on 10 July, the British advanced in groups of twenty, many getting lost but some reached the northern tip of the wood and reported it empty of Germans. To the west, bombing parties took part of Longueval Alley and more fighting occurred at Central Trench in the wood, as German troops advanced again from Guillemont, took several patrols prisoner as they occupied the wood and established posts on the western edge.[77] The 18th (Eastern) Division on the left, was relieved by the 3rd Division on 8 July, having lost 3,400 casualties since 1 July.[78]

By 8:00 a.m. on 10 July, all but the south-eastern part of the wood had fallen to the German counter-attack and a lull occurred, as the 30th Division relieved the 90th Brigade with the 89th Brigade. The remaining British troops were withdrawn and at 2:40 a.m., a huge British bombardment fell on the wood, followed by an attack up Maltz Horn Trench at 3:27 a.m., which killed fifty German soldiers but failed to reach the objective at a strong point, after mistaking a fork in the trench for it. A second battalion advanced north-east, veered from the eastern edge to the south-eastern fringe and tried to work northwards but were stopped by fire from the strong point. The left of the battalion entered the wood further north, took thirty prisoners and occupied part of the eastern edge, as German troops in the wood from I Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 106, II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 182 and III Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 51, skirmished with patrols and received reinforcements from Guillemont. Around noon, more German reinforcements occupied the north end of the wood and at 6:00 p.m., the British artillery fired a barrage between Trônes Wood and Guillemont, after a report from the French of a counter-attack by Reserve Infantry Regiment 106. The attack was cancelled but some German troops managed to get across to the wood to reinforce the garrison, as part of a British battalion advanced from the south, retook the south-eastern edge and dug in.[79]

On 12 July, a new trench was dug from the east side of the wood and linked with those on the western fringe, being completed by dawn on 13 July. German attempts at 8:30 p.m. to advance into the wood, were defeated by French and British artillery-fire. Rawlinson ordered XIII Corps to take the wood "at all costs" and the 30th Division, having lost 2,300 men in five days, was withdrawn and replaced by the 18th (Eastern) Division, the 55th Brigade taking over in the wood and trenches nearby.[80] After a two-hour bombardment on 13 July, the 55th Brigade attacked at 7:00 p.m., a battalion attempting to bomb up Maltz Horn Trench to the strong point near the Guillemont track. A second battalion advanced through the wood, lost direction and stumbled on German posts in Central Trench, until about 150 survivors reached the eastern edge of the wood south of the Guillemont track, thinking that they were at the northern tip of the wood. Attempts to advance north in daylight failed and an attack from Longueval Alley by a third battalion, was stopped by massed small-arms and artillery-fire 100 yd (91 m) short of the wood and the battalion withdrew, apart from a small party, which bombed up the alley to the tip of the wood. With three hours before the big attack on the German second position began, the 54th Brigade was ordered to attack before dawn, to take the eastern fringe of the wood as a defensive flank for the 9th Division, as it attacked Longueval.[81]

Ovillers

A preparatory bombardment began at 2:12 a.m. on 3 July, against the same targets as 1 July but with the addition of the artillery of the 19th (Western) Division. Assembly trenches had been dug, which reduced the width of no man's land from 800–500 yd (730–460 m) at the widest. Two brigades of the 12th Division attacked at 3:15 a.m., with the left covered by a smokescreen. Red rockets were fired immediately by the Germans and answered by field and heavy artillery barrages on the British assembly, front line and communication trenches, most of which were empty, as the British infantry had moved swiftly across no man's land. The four attacking battalions found enough gaps in the German wire, to enter the front trench and press on to the support (third) trench but German infantry "pour[ed]" out of dugouts in the first line, to counter-attack them from behind. At dawn, little could be seen in the dust and smoke, especially on the left, where the smokescreen blew back. Most of the battalions which reached the German line were overwhelmed, when their hand grenades and ammunition ran out, supply carriers not being able to cross no man's land through the German barrage and machine-gun fire. The attack was reported to be a complete failure by 9:00 a.m. and the last foothold on the edge of Ovillers was lost later on.[82]

A company which had lost direction in the dark and stumbled into La Boisselle, took 220 German prisoners but the division had 2,400 casualties. On 7 July, an attack by X Corps on Ovillers was delayed by a German attack, after a bombardment which fell on the 49th Division front near the Ancre, then concentrated on the British position in the German first line north of Thiepval. The survivors of the garrison were forced to retreat to the British front line by 6:00 a.m.[83] A German attack on the Leipzig Salient at 1:15 a.m. from three directions, was repulsed and followed by a bombing fight until 5:30 a.m.; the British attack was still carried out and the rest of the German front line in the Leipzig Salient was captured. The 12th Division and a 25th Division brigade advanced on Ovillers, two battalions of the 74th Brigade on the south side of the Albert–Bapaume road reached the first German trench, where the number of casualties and continuous German machine-gun fire stopped the advance.[84]

On 8 July, German counter-barrage on the lines of the 36th Brigade west of Ovillers, caused many casualties but at 8:30 a.m., the British attacked behind a creeping barrage and quickly took the first three German trenches. Many prisoners were taken in the German dugouts, where they had been surprised by the speed of the British advance. The three German battalions lost 1,400 casualties and withdrew to the second German trench behind outposts; Infantry Regiment 186, II Battalion, Guard Fusiliers and Recruit Battalion 180, had many casualties and withdrew into the middle of the village.[84] In the early hours of 8/9 July, the 12th Division tried to bomb forward but found the deep mud a serious obstacle. The 36th Brigade was reinforced by two battalions and managed to struggle forward 200 yd (180 m) into the village and the 74th Brigade bombed up communication trenches south-west of the village and reached Ovillers church. At 8:00 p.m., the 74th Brigade attacked again and a battalion advanced stealthily to reach the next trench by surprise, then advanced another 600 yd (550 m) by mistake and found itself under a British barrage, until the artillery-fire was stopped and both trenches consolidated.[85]

Before dawn, the 14th Brigade of the 32nd Division relieved the 12th Division, which had lost 4,721 casualties, since 1 July.[85] The divisions of X Corps continued the attack on Ovillers, making slow progress against determined German defenders, who took advantage of the maze of ruins, trenches, dug-outs and shell-holes, to keep close British positions and avoid artillery-fire, which passed beyond them. From 9 to 10 July, three battalions of the 14th Brigade managed to advance a short distance on the left side of the village and on 10 July, a battalion of the 75th Brigade of the 25th Division attacked from the south, as the 7th Brigade tried to get forward from the Albert–Bapaume road, along a trench which led behind the village, against several counter-attacks which were repulsed. A battalion of the 96th Brigade managed an advance overnight in the north-west of the village. On the night of 12/13 July, two battalions attacked from the south-east and south as the 96th Brigade attacked from the west, advanced a short distance and took a number of prisoners. The battle for Ovillers continued during the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July).[86]

Thiepval

A new attack was planned against Thiepval for 2 July by the 32nd and 49th divisions of X Corps and the 48th Division of VIII Corps was cancelled and replaced by an attack by the 32nd Division, on the east end of the Leipzig Redoubt and the Wundtwerk (Wonderwork to the British) on a front of 800 yd (730 m), by the 14th Brigade and the 75th Brigade attached from the 25th Division. Information about the changed plan reached X Corps late and only reached the 32nd Division commander at 10:45 p.m. along with an increase in the attack frontage to 1,400 yd (0.80 mi; 1.3 km) north to Thiepval Chateau. With most telephone lines cut the artillery were not told of the postponement, until half of the bombardment for the original 3:15 a.m. zero hour had been fired. A new bombardment on the wider front had only half the ammunition. After repulsing two German counter-attacks, two companies advanced from the tip of the Leipzig Salient and reached the German front trench at 6:15 a.m. and were then forced back out. The left-hand brigade attacked with three battalions, which on the flanks found uncut wire and whose leading waves were "mown down" by German machine-gun fire; the few who got into the German front trench being killed or captured, except for a few who reached the Leipzig Salient. The centre battalion reached the German front trench but was eventually bombed out by II Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 99 and a company from Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 8. The supporting waves had taken cover in shell-holes in no man's land; then were ordered back having lost c. 1,100 casualties. The 32nd Division was relieved by the 25th Division on the night of 3/4 July with casualties of 4,676 men since 1 July.[87] On 5 July, the 25th Division attacked at 7:00 p.m. to extend its hold on Leipzig Redoubt and gained a foothold in Hindenburg Trench.[88]

30 January – 30 June

From 30 January 1916, each British army in France had a Royal Flying Corps brigade with a corps wing containing squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front held by the army and an army wing for long-range reconnaissance and bombing, its squadrons using aircraft types with the highest performance.[89] On the Somme front Die Fliegertruppen des Deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps) had six reconnaissance flights (Feldflieger-Abteilungen) with 42 aircraft, four artillery flights (Artillerieflieger-Abteilungen) with 17 aeroplanes, a bomber-fighter squadron (Kampfgeschwader I) with 43 aircraft a bomber-fighter flight (Kampfstaffel 32) with 8 aeroplanes and a single-seat fighter detachment (Kampfeinsitzer-Kommando) with 19 aircraft, a strength of 129 aeroplanes.[90]

Some of the German air units had recently arrived from Russia and lacked experience of Western Front conditions, some aircraft were being replaced and many single-seat fighter pilots were newly trained. German air reconnaissance had uncovered British–French preparations for the Somme offensive and after a period of bad weather in mid-June, French preparations were also seen as far south as Chaulnes.[91] British aircraft and kite balloons, were used to observe the intermittent bombardment, which began in June and the preliminary bombardment which commenced on 24 June. Low cloud and rain obstructed air observation of the bombardment, which soon fell behind schedule; on 25 June aircraft of the four British Armies on the Western Front, attacked the German kite balloons opposite, four were shot down by rockets and one bombed, three of the balloons being in the Fourth Army area. Next day, three more balloons were shot down opposite the Fourth Army. During German artillery retaliation against the British–French bombardment, 102 German artillery positions were plotted and a Fokker was shot down near Courcelette.[92]

1 July

Accurate observation was not possible at dawn on 1 July, due to patches of mist but by 6:30 a.m. the general effect of the British–French bombardment could be seen. Observers in contact aircraft watched lines of British infantry crawl into no man's land, ready to attack the German front trench at 7:30 a.m. Each corps and division had a wireless receiving-station, to take messages from airborne artillery-observers and observers on the ground were stationed at various points, to receive messages and maps dropped from aircraft.[93] As contact observers reported the progress of the infantry attack, artillery-observers sent many messages to the British artillery and reported the effect of counter-battery fire on German artillery. Balloon observers used their telephones, to report changes in the German counter-barrage and to direct British artillery on fleeting targets, continuing during the night by observing German gun-flashes. Air reconnaissance during the day, found little movement on the roads and railways behind the German front but the railways at Bapaume were bombed from 5:00 a.m. Flights to Cambrai, Busigny and Etreux later in the day saw no unusual movement and German aircraft attacked the observation aircraft all the way to the targets and back, two Rolands being shot down by the escorts. Bombing had begun the evening before, with a raid on the station at St Saveur by six R.E. 7s of 21 Squadron, whose pilots claimed hits on sheds; a second raid around 6:00 a.m. on 1 July, hit the station and railway lines. Both attacks were escorted and two Fokkers were shot down on the second raid.[94]

Railway bombing by 28 aircraft, each carrying two 112 lb (51 kg) bombs, began after noon and Cambrai station was hit with seven bombs, for the loss of one aircraft. In the early evening, an ammunition train was bombed on the line between Aubigny-au-Bac and Cambrai and set on fire, the cargo burning and exploding for several hours. Raids on St Quentin and Busigny were reported to be failures by the crews and three aircraft were lost.[95] German prisoners captured by the French army later in July, reported that they were at the station during the bombing, which hit an ammunition shed near 200 ammunition wagons. Sixty wagons caught fire and exploded, which destroyed the troop train and two battalions' worth of equipment piled on the platform, killing or wounding 180 troops, after which Reserve Infantry Regiment 71 had to be sent back to re-equip.[96]

All corps aircraft carried 20 lb (9.1 kg) bombs to attack billets, transport, trenches and artillery-batteries. Offensive sweeps were flown by 27 Squadron and 60 Squadron from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. but found few German aircraft and only an LVG was forced down. Two sets of patrols were flown, one by 24 Squadron in Airco DH.2s from Péronne to Pys and Gommecourt from 6:45 a.m. to nightfall, which met six German aircraft during the day and forced two down. The second set of patrols by pairs of Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2bs were made by 22 Squadron between 4:12 a.m. and dusk, from Longueval to Cléry and Douchy to Miraumont. The squadron lost two aircraft and had one damaged but kept German aircraft away from the corps aircraft.[97]

2 July

On 2 July, the Fifteenth Wing RFC was formed for the Reserve Army; 4 Squadron and 15 Squadrons, which had been attached to X Corps and VIII Corps, were taken over from the Third Wing, 1 and 11 Kite Balloon sections became the corps sections and 13 Section became the army section, all protected by the Fourteenth (army) Wing.[98] On 2 July, the 17th (Northern) Division attack on Fricourt Farm was watched by observers on contact patrol, who reported the capture within minutes and observers of 3 Squadron reported the course of the attack on La Boisselle. One aircraft took a lamp message at about 10:00 p.m., asking for rifle grenades and other supplies, which was immediately passed on. An observer in the 12 Section balloon, spotted a German battery setting up at the edge of Bernafay Wood and directed fire from a French battery; the German guns were soon silenced and captured a few days later. On 2 July, air reconnaissance found little extra railway activity, apart from ten trains moving from Douai to Cambrai, thought to by carrying reinforcements from Lens. A raid by 21 Squadron on Bapaume, using 336 lb (152 kg) bombs, hit headquarters and ammunition dumps, which started fires that burned into the night. On the Fourth and Third army fronts, seven air combats took place and four German aircraft were forced to land.[99]

3 July

Early morning reconnaissance flights on 3 July, found many trains around Cambrai and reinforcements arriving from the east and south-east, heading towards Bapaume and Péronne. Pairs of British pilots began operations at 5:30 a.m. but attempts to bomb moving trains failed. German aircraft intercepted the first pair of bombing aircraft and forced them to turn back but the next two from I Brigade, managed to bomb Busigny station. Two aircraft sent to bomb St Quentin were intercepted and chased back to the British lines and the next pair was caught by anti-aircraft fire at Brie, one pilot turning back wounded and the other disappearing. Of five aircraft which attacked Cambrai, two were shot down, one was damaged by return fire from a train being attacked and the other two failed to hit moving trains. An offensive patrol by 60 Squadron during the bombing raids, lost one aircraft to a Fokker.[100]

In two days, eight bombers were lost and most of the other aircraft were badly damaged, despite offensive patrols intended to protect the bombing aircraft, which were flown without observers. Trenchard stopped the low bombing of trains and returned to escorted formation bombing.[100] In the afternoon, three aeroplanes from 21 Squadron, attacked Cambrai again and hit buildings south of the station. In the evening, air observers were able to plot the progress of the attack on La Boisselle, by spotting flares lit by ground troops and an observer from 9 Squadron, who examined Caterpillar Wood from 500 ft (150 m) found it unoccupied, as did an observer who examined Bernafay Wood, which led to the wood being captured that evening and Caterpillar Wood being taken overnight.[101]

4–12 July

4 July was rainy, with low cloud and no German aircraft were seen by British aircrew, who flew low over the German lines, on artillery-observation sorties. In the evening, a large column of German troops was seen near Bazentin le Grand and machine-gunned from the air and the British advance to the southern fringe of Contalmaison was observed and reported. On 6 July, German positions near Mametz Wood and Quadrangle Support Trench were reconnoitred by a 3 Squadron crew, which reported that the defences of Mametz Wood were intact. On 6 July, a 9 Squadron observer saw infantry and transport near Guillemont and directed the fire of a heavy battery on the column, which inflicted many casualties; a German infantry unit entering Ginchy was machine-gunned and forced to disperse. Later in the evening, the crew returned and directed artillery onto more German troops near Ginchy, prisoners later claiming that the battalion lost half its men in the bombardment.[102] Infantry attacks on 7 July, made very slow progress and observers from 3 Squadron reported events in the late afternoon and evening. A crew which flew behind a German barrage saw Quadrangle Support Trench suddenly fill up with troops in field grey uniforms, who repulsed a British attack. British observers were overhead and saw continuous attacks and counter-attacks by both sides until midnight on 10/11 July, when Mametz Wood and Quadrangle Support Trenches were captured.[103]

The battle for Trônes Wood was also followed by observation-aircraft and at 8:00 p.m. on 12 July, a 9 Squadron observer saw a German barrage fall between Trônes Wood and Bernafay Wood. The observer called by wireless for an immediate counter-barrage, which obstructed a German counter-attack at 9:00 p.m. so badly, that the German infantry were easily repulsed.[103] Bombing of German-controlled railway centres continued on 9 July, with attacks on Cambrai and Bapaume stations, in which two British aircraft were lost. Le Sars and Le Transloy were attacked in the afternoon and Havrincourt Wood was bombed on 11 July, after suspicions had been raised by increasing amounts of German anti-aircraft fire around the wood. Twenty bombers with seventeen escorts, dropped 54 bombs on the wood and started several fires. On 13 July, a special effort was made to attack troop-trains on the Douai–Cambrai and Valenciennes–Cambrai lines. One train was derailed and overturned near Aubigny-au-Bac and a train was bombed on the Cambrai–Denain line, the British pilots making use of low cloud to evade German attempts to intercept them.[104]

German 2nd Army