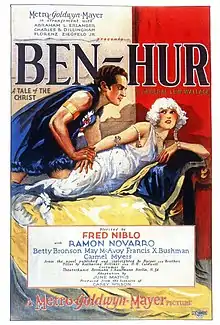

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925 film)

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ is a 1925 American silent epic adventure-drama film directed by Fred Niblo and written by June Mathis based on the 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace. Starring Ramon Novarro as the title character, the film is the first feature-length adaptation of the novel and second overall, following the 1907 short.

| Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

| Budget | $4 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $10.7 million[1][2] |

In 1997, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[3][4]

Plot

Ben-Hur is a wealthy young Jewish prince and boyhood friend of the powerful Roman tribune, Messala. When an accident and a false accusation leads to Ben-Hur's arrest, Messala, who has become corrupt and arrogant, makes sure Ben-Hur and his family are jailed and separated.

Ben-Hur is sentenced to slave labor in a Roman war galley. Along the way, he unknowingly encounters Jesus, the carpenter's son who offers him water. Once aboard ship, his attitude of defiance and strength impresses a Roman admiral, Quintus Arrius, who allows him to remain unchained. This actually works in the admiral's favor because when his ship is attacked and sunk by pirates, Ben-Hur saves him from drowning.

Arrius then treats Ben-Hur as a son, and over the years the young man grows strong and becomes a victorious chariot racer. This eventually leads to a climactic showdown with Messala in a chariot race, in which Ben-Hur is the victor. However, Messala does not die, as he does in the more famous 1959 adaptation of the novel.

Ben-Hur is eventually reunited with his mother and sister, who have developed leprosy but are miraculously cured by Jesus Christ.[5]

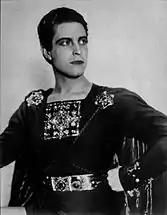

Cast

.jpg.webp)

|

Main

|

Some notable crowd extras during chariot race

|

Production

Ben-Hur: A Tale of The Christ had been a great success as a novel, and was adapted into a stage play which ran for twenty-five years. In 1922, two years after the play's last tour, the Goldwyn company purchased the film rights to Ben-Hur. The play's producer, Abraham Erlanger, put a heavy price on the screen rights. Erlanger was persuaded to accept a generous profit participation deal and total approval over every detail of the production.

Choosing the title role was difficult for June Mathis. Rudolph Valentino and dancer Paul Swan were considered until George Walsh was chosen. When asked why she chose him, she answered it was because of his eyes and his body. Gertrude Olmstead was cast as Esther.[7][8] While on location in Italy, Walsh was fired and replaced by Ramon Novarro.[6] The role of Esther went to May McAvoy.

Shooting began in Rome, Italy in October 1923 under the direction of Charles Brabin who was replaced shortly after filming began. Other re-castings (apart from Ramon Novarro as Ben-Hur) and a change of director caused the production's budget to skyrocket. After two years of difficulties and accidents, the production was eventually moved back to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Culver City, California and production resumed in the spring of 1925. B. Reeves Eason and Christy Cabanne directed the second unit footage.[9]

Production costs eventually rose to $3,900,000 ($65,080,000 today) compared to MGM's average for the season of $158,000 ($2,640,000 today),[2] making Ben-Hur the most expensive film of the silent era.[10]

A total of 200,000 feet (61,000 m) of film was shot for the chariot race sequence, which lead editor Lloyd Nosler eventually cut to 750 feet (230 m) for the released print.[11] Film historian and critic Kevin Brownlow has described the race sequence as "breathtakingly exciting, and as creative a piece of cinema as the Odessa Steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin", the Soviet film also released in 1925, directed by Sergei Eisenstein who introduced many modern concepts of editing and montage composition to motion-picture production.[12] Visual elements of the chariot race have been much imitated. The race's opening sequence was re-created shot-for-shot in the 1959 remake, copied in the 1998 animated film The Prince of Egypt, and imitated in the pod race scene in the 1999 film Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[13][14]

Some of the scenes in the 1925 film were shot in two-color Technicolor, most notably the sequences involving Jesus. One of the assistant directors for this sequence was a young William Wyler, who would direct the 1959 MGM remake. The black-and-white footage was color tinted and toned in the film's original release print. MGM released a second remake of Ben-Hur in 2016.[9]

Reception

.jpg.webp)

The studio's publicity department was relentless in promoting the film, advertising it with lines like: "The Picture Every Christian Ought to See!" and "The Supreme Motion Picture Masterpiece of All Time". Ben Hur went on to become MGM's highest-grossing film, with rentals of $9 million worldwide. Its foreign earnings of $5 million were not surpassed at MGM for at least 25 years. Despite the large revenues, its huge expenses and the deal with Erlanger made it a net financial loss for MGM. It recorded an overall loss of $698,000.[2]

In terms of publicity and prestige however, it was a great success. "The screen has yet to reveal anything more exquisitely moving than the scenes at Bethlehem, the blazing of the star in the heavens, the shepherds and the Wise Men watching. The gentle, radiant Madonna of Betty Bronson's is a masterpiece," wrote a reviewer for Photoplay. "No one," they concluded, "no matter what his age or religion, should miss it. And take the children."[15] It helped establish the new MGM as a major studio.[16][17]

The film was re-released in 1931 with an added musical score, by the original composers William Axt and David Mendoza, and sound effects. As the decades passed, the original two-color Technicolor segments were replaced by alternative black-and-white takes. Ben-Hur earned $1,352,000 during its re-release, including $1,153,000 of foreign earnings, and made a profit of $779,000 meaning it had an overall profit of $81,000.[2] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 96% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 23 reviews, with an average rating of 7.8/10.[18]

The film became controversial after its release for the harm to animals involved in the filming. A reported one hundred horses were tripped and killed merely to produce the set piece footage of the major chariot race. Animal advocates especially criticized the use of the "running W" on set, a wire device that could trip a galloping horse. It would take a decade before such devices lost favor in Hollywood.[19]

The movie was banned in the 1930s in China under the category of "superstitious films" due to its religious subject matter involving gods and deities.[20]

Restoration

The Technicolor scenes were considered lost until the 1980s when Turner Entertainment (who by then had acquired the rights to the MGM film library) found the crucial sequences in a Czechoslovakian film archive. Current prints of the 1925 version are from the Turner-supervised restoration which includes the color tints and Technicolor sections set to resemble the original theatrical release. There is an addition of a newly recorded stereo orchestral soundtrack by Carl Davis with the London Philharmonic Orchestra which was originally recorded for a Thames Television screening of the movie.

Home media

Ben-Hur was released on DVD, complete with the Technicolor segments, in the four-disc collector's edition of the 1959 version starring Charlton Heston, as well as in the 2011 "Fiftieth Anniversary Edition" Blu-ray Collector's Edition three-disc box set.

See also

- List of early color feature films

- List of films featuring slavery

- Francis X. Bushman filmography

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- "Ben-Hur (1925)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- H. Mark Glancy, 'MGM Film Grosses, 1924–28: The Eddie Mannix Ledger', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 12 No. 2 1992 pp. 127–44 at p. 129

- "New to the National Film Registry (December 1997) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "Plot Summary for Ben Hur". Classic Film Guide. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- Keel, A. Chester (November 1924). "The Fiasco of Ben Hur". Photoplay. Chicago, Illinois: Photoplay Magazine Publishing Company. 26 (6): 32–33, 101.

- Marshall, Eunice (April 1924). "What Will Happen to Ben-Hur?". Screenland. New York. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- Marshall, Eunice (April 1924). "What Will Happen to Ben-Hur? (Continued)". Screenland. New York. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- "Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ". silentera.com. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (April 15, 2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Wayne State University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1968). The Parade's Gone By... New York: Bonanza Books. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-5200-3068-8.

- Brownlow, p. 413.

- Bowman, James (1998). "Prince of Egypt, The", article published 1 December 1998, online journal of the Ethics and Public Policy Center (EPPC), Washington, D.C. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- MrRazNZ (2021). The Pod Race: How George Lucas copied, transformed and combined" on YouTube, scene-by-scene video comparison of race in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace with the races in Ben Hur and in the 1975 Norwegian stop-motion animated feature The Pinchcliffe Grand Prix; uploaded 12 August 2021 to YouTube (San Bruno, California). Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- "The Shadow Stage". Photoplay. New York. March 1926. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- Hoffman, Scott W. (2002). "The Making and Release of Ben-Hur". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2021 – via BNET.

- Hagopian, Kevin. "Film Notes: Ben-Hur". New York State Writers Institute. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- "Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1926)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- "8 troubling tales of animal abuse on film shoots". The Week. November 19, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- Yingjin, Zhang (1999). Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922–1943. Stanford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8047-3572-8.

Further reading

- Keel, A. Chester, "The Fiasco of 'Ben Hur'," Photoplay, November 1924, p. 32.

External links

- Ben-Hur essay by Fritzi Kramer at National Film Registry.

- Ben-Hur essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 109-111

- Ben-Hur at IMDb

- Ben-Hur at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Ben-Hur at the TCM Movie Database

- Ben-Hur at AllMovie

- Ben-Hur at Rotten Tomatoes

- Ben-Hur: original score composed for the film by David Mendoza and William Axt at the International Music Score Library Project