Breton nationalism

Breton nationalism (Breton: Broadelouriezh Brezhoneg, French: nationalisme Breton) is a form of regional nationalism associated with the region of Brittany in France. The political aspirations of Breton nationalists include the desire to obtain the right to self-rule, whether within France or independently of it, and to acquire more representation within the European Union, United Nations, and other international institutions.

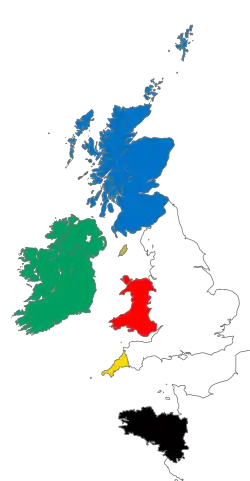

Breton nationalism emerged in various forms over time, which nationalists consider to fall into phases known as "renovations" (emsav). The First Emsav was the birth of the modern Breton movement before 1914; the Second Emsav covers the period 1914-1945; and the Third Emsav for the postwar movements. Breton nationalism has an important cultural component which has long focused on the defense of the Breton and Gallo languages against the French Republic's policies of linguistic imperialism and coercive Francization through the State educational system. Instead, Breton nationalists favor language revival and the expansion of Breton-medium education. They have also been interested in both reviving and preserving the region's uniquely Celtic culture, music and symbols and have occasionally professed forms of pan-Celticism.

Positioning within the Breton movement

The academic Michel Nicolas describes this political tendency of the Breton movement as "a doctrine putting forward the nation, in the state and non-state framework". According to him, the people belonging to this tendency can choose to present themselves as separatists or independentists, that is to say claiming the right to "any nation to a state, and if necessary must be able to separate to create one".[1]

He thus opposes it to regionalism which aims at it for a "administrative redeployment granting autonomy at regional level" (that is to say autonomist), and at the Breton federalism which seeks it to set up a federal organization of the territory.[1]

History

Background

Prior to the expansion of the Roman Empire into the region, Gallic tribes had occupied the Armorican peninsula, dividing it into five regions that then formed the basis for the Roman administration of the area, and which survived into the period of the Duchy.[2] These Gallic tribes (termed the Armorici in Latin), had close relationships with the Britonnes tribes in Roman Britain.[3] Between the late 4th and the early 7th centuries, many of these Britonnes migrated to the Armorican peninsula, blending with the local people to form the later Britons,[4] who eventually became the Bretons.[5] These migrations from Britain contributed to Brittany's name, while also shaping its ethnic and linguistic identity.[6] Brittany was divided into small, warring kingdoms, each competing for resources.[7] The Frankish Carolingian Empire conquered the region during the 8th century, starting around 748 and taking the whole of Brittany by 799.[8] In 831, Louis the Pious appointed Nominoe, the Count of Vannes, as imperial missus dominicus for Brittany. The death of Louis, in 840, sparked a civil war that fragmented the realm, enabling Nominoe to assert his authority over the former March of Brittany. In 846, the ruler of West Francia, Charles the Bald, signed a peace treaty with Nominoe, recognizing him as the first duke of Brittany.[9]

Following his marriage to Claude, the Duchess of Brittany, Francis I of France secured the Union of Brittany and France. On 13 August 1532, the Estates of Brittany confirmed the arrangement by signing the Edict of Union. Upon the death of Francis III, Duke of Brittany in 1536, the Duchy of Brittany passed to Dauphin Henry - later Henry II of France. Henry's status from 1547 as king of France meant that the duchy became merely a French province. Institutions such as the Breton Estates and Parlement of Brittany continued to resist Paris in matters of taxation until their dissolution at the end of the 18th century.[10][11] Breton nationalism saw a revival following the 1839 publication of Barzaz Breiz, a collection of traditional Breton folktales, songs and music. Pitre-Chevalier's 1844 Histoire de la Bretagne, followed in the same footsteps by highlighting a number of historical events as manifestations of Breton nationalism and aspirations of independence. Chevalier did not hesitate to distort the causes of revolts, such as the Revolt of the papier timbré, in order to promote his agenda. The end of the 19th century was marked by the disintegration of archaic Breton social and economic structures with a parallel drive for compulsory primary education. During the course of the latter, primary teachers were specifically instructed with the phasing out of minority languages. Early Breton nationalist organizations, such as Association Brettone (founded in 1829), focused on issues such as the preservation of the Breton language and administrative autonomy. By 1914, the Breton language had been embraced by the region's intellectuals through a literary revival; however, it failed to reach the masses.[12]

D'Ar Bobl to the Breton nationalist party

Several authors, cultural groups, or regionalist political groups, use the expression of "Breton nation" as from 19th century but without this one falls under nationalist dimension. It is only at the beginning of the 20th century that a nationalist current in Brittany began to be constituted. Imitating the French nationalism of the time, they focused their speech on the defense of Breton language and valorization of the history of Brittany; however, it distinguished itself by seeking to legitimize its action by comparing themselves with those of other European minorities, "Celts" in particular, like those of Wales and especially of Ireland.[13]

By the end of the 1900s, the journal Ar Bobl of Frañsez Jaffrennou began to spread ideas close to this ideology,[14] but 1911 is a key date for this current. The inauguration of a work by Jean Boucher in a niche of the City Hall of Rennes, depicted the Duchess Anne of Brittany kneeling before the King of France Charles VIII, causing an opposition movement in the regionalist movements. An activist, Camille Le Mercier d'Erm, disrupted the inauguration, and used her trial as a platform. This was the first public expression of a Breton nationalism. Following this event, a group of students in Rennes founded the Breton Nationalist Party, which began with several members of the Regionalist Federation of Brittany, with the aim of to break with the regionalist ideas of this group.[15] Among its first members were Louis Napoleon Le Roux, Aogust Bôcher, Pol Suliac, Joseph du Chauchix, Joseph Le Bras, Job Loyant,[14] but their numbers hardly went beyond the 13 members of the editorial board of Breiz Dishual.[16]

First strategic positioning

The group was at odds with Breton regionalism, which it accused of ratifying a foreign influence, that of France, in Brittany. Seeking to apply the principle of subsidiarity, that is claiming a decentralization with a redistribution of powers, would be equivalent, according to the nationalists, to legitimizing a French domination. They opposed as much to monarchists (in particular by maintaining controversy with the members of the French Action), than to the Republicans by targeting "black hussars of the republic", accused of pursuing a policy of linguistic repression. In 1912, Breiz Dishual, the newspaper of the BNP, thus formulated for the first time this opposition towards the royalists and the republicans with the expression na ru na gwenn, Breizhad hepken[17] ("neither red nor white, Breton only"), picked up in the following decades by different trends. The nationalists thus refused to support certain circles such as the landed aristocracy or the urban bourgeoisie, considered to be compromised.[18] It was also within this first group that the first Federalist ideas appeared from April 1914 in Breiz Dishual.[16]

This current was also positioned face to face with events and international actors, especially in the Pan-Celtic current. Breiz Dishual, indicated from its first issue of July 1912 to want to take an example of the Irish nationalists methods.[19] This comparison between the Breton and Irish situations of the time is not peculiar to the Breton nationalist movement, and is also found among outside observers, such as Simon Südfeld for the liberal German newspaper Vossische Zeitung in 1913.[20] The Breton Nationalist Party as its newspaper Breiz Dishual, however, have only limited echoes in the Breton movement of the time, and his nationalism can only find a weak resonance. One of its founders, Louis Napoleon Le Roux, would play a role later to make the link between Breton nationalist currents and Irish.[21] It was also inspired by other European examples such as Hungary, Catalonia, Norway, and the Balkan States,[22] and inscribed its reflection on a European scale.[16]

The Breton Nationalist Party ceased to exist in 1914 on the outbreak of World War I in August that year. Its journal Breiz Dishual ceased publication at the same time.[23]

Breton regional group at the Unvaniez Yaouankiz Vreiz

After the World War I, the nationalist current continued its existence, becoming one of the most dynamic components of the Breton movement in the 1920s. The Breton Regionalist Group was the first party created (September 1918) taking up this ideology, mixing elders of the Breton Nationalist Party as Kamil Ar Merser 'Erm, and newcomers like Olier Mordrel, Frañsez Debauvais, Yann Bricler, and Morvan Marchal;[24] it was endowed as soon as January 1919 of a newspaper, Breiz Atao, to spread their ideas.[25] The adjective "regionalist" was preferred to that of "nationalist", on the one hand because the French State of the time tolerated little separatist ideas,[26] and secondly because it made it possible to forge links with the Breton bourgeoisie of the Regionalist Federation of Brittany.[25]

The ideology of the group was initially[24] and partially[25] in a "Maurrasian movement",[24][25] but quickly moved into a nationalism more and more affirmed.[27] The Breton Regionalist Group took the name of Unvaniez Yaouankiz Vreiz in May 1920, whose status indicated that it aimed at a "return to national independent life". Breiz Atao also evolved by taking as subtitle "monthly magazine of Breton nationalism" in January 1921, then that of "the Breton nation" in July of the same year.[28]

Attempt, from Breton regionalism, to Alsatian autonomy, to Irish nationalism

The nationalists aimed at first not to support the Breton population, but on their economic circles. They intended to become the thinking head in this elitist process. Frañsez Debauvais cites René Johannet in this way in the Breiz Atao of April 1921.[28] They thus came into competition with the regionalism of the Regionalist Federation of Brittany, and the relations between the two groups were therefore strained.[29] Antagonism was reinforced in 1920 when the BRF claimed the creation of a large western region encompassing Poitou, Anjou, Maine, Cotentin and Brittany,[30] provoked a unanimous rejection of other regionalist groups, as well as nationalists.[31] From then on, the nationalists' discourse became profoundly anti-regionalist, accusing them of falling into "biniousery" and "bretonnerie".[29]

The nationalists also sought to get out of the French political markers of the time, left and right, and take up the slogan "na ru na gwenn, Breiziz hepken" already used by the first nationalists.[29] This positioning was reinforced by the fact that no French political party paid attention to the demands expressed by the regions. They also sought to emancipate themselves from the Church and the clerical milieus from which the regionalists come, claiming a Celtic heritage, the Catholic religion was alienating to the Bretons.[32] The Alsatian affair in 1926, during which the Cartel des Gauches tried to return to the Concordat in Alsace-Moselle, caused an autonomist agitation in this region, and the Breton nationalists took support on this example to decide to form a political party.[33]

The examples also came from abroad. Ireland was the main center of attention since the end of the 1910s: Home Rule movement,[27] then the Irish declaration of independence of 1919, and finally its independence in 1921 strengthened the nationalists in the path of secession.[29] The attempt to establish a certain form of autonomy in Wales in 1922 was another landmark for this trend.[34]

Grouping within the Breton National Party

The Breton National Party was created in 1931 and recovered from the name Breiz Atao for its new magazine, after the Breton Autonomist Party chose to rename its publication in La Bretagne Fédérale.[35] Bringing together the nationalist current from the Breton Autonomist Party, it counted at its first congress in Landerneau on December 27, 1931 only 25 members.[36] It had only limited activity in its early years, although the 7 August 1932 attacks in Rennes brought it some publicity, even some credibility in the media.[37] Its numbers are however limited, and in 1940 it could only count on about 300 militants.[38]

Politically, it asserted the existence of a Breton nation, and thus claimed the independence of this one. Claiming to be apolitical,[36] claiming "the sacred union of all Britons", it nevertheless expressed an anti-communism[37] and a marked anti-socialism.[39] The French political evolution of the time marginalized this trend. Leftist political groups showed great hostility towards it, and no support could be found within the French Popular Front. The French far-right also fought any form of autonomism, and no alliance could be tied.[40] The year 1936 also marked a turning point in the attitude of the French authorities towards the autonomist movements which then become less conciliatory, and Daladier's rise to power in 1938 strengthened the fight against these groups.[41] Daladier's decree-law of May 25, 1938 which reinstated the offense of opinion regarding national integrity affected several BNP militants, including its director Debauvais who spent seven months in prison.[42] On October 20, 1939, the BNP like other parties was banned and dissolved. Two of its executives, Debeauvais and Mordrel fled into Germany[43] while other activists let themselves be mobilized.[44] At the regional level, it was opposed from its inception to the War Sao party,[37] and federalists of the Breton Federalist League mocked the SAGA program published by Mordrel in 1933.[38]

The geopolitical situation of the time offered to the Breton nationalist current an opening with the setting up in 1933 of Nazi Germany besides the Rhine. Betting on a victory of Germany in case of war with France,[38] it then developed an interested pacifist propaganda, calling for the neutrality of the Bretons in case of war involving France, or to refuse a "war for the Czechs". They sought to attract the goodwill of the German secret services, while some members of the BNP as Mordrel were already in contact with them.[38]

From pan-Celticism to racialism

Ideologically, the Breton National Party put the Breton national question before the social question, believing that it would be solved once independence was obtained.[45] Reactionary and right-wing in orientation, but capable of attracting left-wing personalities such as Yann Sohier, it was dominated by a militant base from small Breton towns.[45] The "na gwenn na ruz" orientation continued to be used by the nationalist movement, and initially rejected the fascist/anti-fascist divide that was expressed at the time.[46]

Pan-Celticism continued to be used by nationalists, while the federalists abandoned this idea.[45] They stood out, however, from the regionalists who were also active in this area via the Goursez Vreizh, but whose actions the nationalists mocked.[47] The Irish example continued to be celebrated by the Breton nationalists during the 1930s, notably in 1936 to mark the 20th anniversary of the Easter Rising.[48] It served as an example for the creation of the armed group Gwenn ha Du, modeled on the Irish Republican Army.[49] In contrast, the actions of the Welsh nationalists led by Saunders Lewis, although welcomed, were considered too non-violent,[41] like those of the Scottish nationalists of the Scottish National Party.[50] However, from 1937 this pan-Celticism dimension among the nationalists seemed to fade against other international issues,[46] and these displayed orientations that were increasingly pro-Nazi.[49]

An ultranationalist and overtly racist trend was also beginning to gain influence within the nationalist movement during this decade, on the sidelines of the Breton National Party, and sometimes outside it.[45] Olier Mordrel published in 1933 the "SAGA program" in the Breiz Atao, advocating strong state and corporate capitalism, as well as exclusion of foreigners from public posts.[51] It published, from July 1934, the journal Stur in which it elaborated a doctrine which served as an ideological base for the nationalists. It was openly racist, prefiguring a collaboration with the Nazi regime.[52] Mordrel praised the Italian fascist regime in 1935, leased the Nazi German regime in 1936, and there advocated the purity of the race of "Nordic Breton type" in 1937. The same year at the congress of Carhaix, the BNP endorsed this ideological evolution.[51] In this perspective, pan-Celticism continued to be used to make the link between "Celts" and "Germans" within the same "Nordic" community.[45] However these ideas at the time, only gathered a minority of militants.[53]

World War II

During World War II, the organized political movement as a whole collapsed in the collaboration with the Nazi occupier and/or with the Vichy regime.[54]

The behavior of each other is the object of a selective omission of war which always feeds polemics more than seventy years later: "In reality, at the Liberation, within the Breton movement, we minimize the collaboration, we create the myth of the wild épuration"[55]

About 15 to 16% of members of the BNP have been brought to court, few are the sympathizers to have been judged. What makes the Épuration an epiphenomenon whose reality is very far from the mythical image of a massive repression, maintained by the traumatized memory of the Breton nationalists.[56]

The behavior of the Breton nationalists, which for some historians, harmed Breton culture:

This culture of foreign hatred and scorn of the people who inhabited the nationalists led them to bring into disrepute for a long time the interest for the Breton language and culture in the region, or even to allow the Bretoners to justify the abandonment of the Breton language. However, in December 1946, at the initiative of the public authorities, Pêr-Jakez Helias launched a new program of radio programs in Breton on Quimerc'h Radio.[57]

Contemporary parties

- Contemporary political parties or movements holding Breton nationalist views are the Unvaniezh Demokratel Breizh, Breton Party, Emgann, Adsav, Breizh Yaouank and Breizhistance.

Opinion polling

According to an opinion poll conducted in 2013, 18% of Bretons support Breton independence. The poll also found that 37% would describe themselves as Breton first, while 48% would describe themselves as French first.[58]

See also

References

- Nicolas 2007, p. 33

- Jones 1988, p. 2.

- Galliou & Jones 1991, p. 130.

- Galliou & Jones 1991, p. 128.

- Galliou & Jones 1991, pp. 130–131.

- Jones 1988, pp. 2–3.

- Smith 1992, pp. 20–21.

- Price 1989, p. 21.

- O'Callaghan 1982, pp. 16–17.

- O'Callaghan 1982, pp. 31–33.

- Leach 2010, p. 631.

- O'Callaghan 1982, pp. 51–55.

- Chartier 2010, p. 265

- Nicolas 2007, p. 64

- Chartier 2010, p. 266

- Nicolas 2007, p. 68

- Mordrel Olier (1973). Breiz Atao - History and news of Breton nationalism. Alain Moreau. OCLC 668861.

- Nicolas 2007, p. 65

- Chartier 2010, p. 267

- Chartier 2010, p. 268

- Chartier 2010, p. 270

- Nicolas 2007, p. 67

- Theodore Zeldin, A History of French Passions 1848-1945, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 62

- Chartier 2010, p. 314

- Nicolas 2007, p. 69

- Nicolas 2012, p. 32

- Chartier 2010, p. 315

- Nicolas 2007, p. 70

- Nicolas 2007, p. 71

- Chartier 2010, p. 332

- Chartier 2010, p. 261

- Nicolas 2007, p. 72

- Nicolas 2007, p. 73

- Chartier 2010, p. 319

- Nicolas 2007, p. 75

- Nicolas 2007, p. 76

- Nicolas 2007, p. 77

- Nicolas 2007, p. 80

- Nicolas 2007, p. 78

- Nicolas 2007, p. 79

- Chartier 2010, p. 425

- Chartier 2010, p. 441

- Nicolas 2007, p. 88

- Nicolas 2007, p. 81

- Chartier 2010, p. 422

- Chartier 2010, p. 426

- Chartier 2010, p. 423

- Chartier 2010, p. 424

- Chartier 2010, p. 427

- Chartier 2010, p. 433

- Cadiou 2013, p. 295

- Chartier 2010, p. 431

- Chartier 2010, p. 439

- Michel Nicolas, Histoire du mouvement breton, Syros, 1982, p. 102 ; Alain Déniel, p. 318

- Ronan Calvez, Radio in Breton language: Roparz Hemon and Pierre-Jakez Hélias: two dreams of Brittany, University Press of Rennes, 2000, 330 pages, p. 91 ISBN 2868475345.

- "Bretagne et identités régionales pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale". Fondation de la Résistance (in French).

- report of the book by Luc Capdevila published in the n° 73 2002/1 of Vingtième Siècle : Revue d'histoire, pp. 211-237

- "One in five Bretons want independence: poll". thelocals.fr. 29 January 2013.

Bibliography

- Cadiou, Georges (2013). EMSAV : dictionnaire critique, historique et biographique : le mouvement breton de A à Z du XIXe siècle à nos jours. Spézet: Coop Breizh. ISBN 9782843465741.

- Chartier, Erwan (2010). La construction de l'interceltisme en Bretagne, des origines à nos jours : mise en perspective historique et idéologique (PDF) (PhD) (in French). Université Européenne de Bretagne. HAL tel-00575335v1.

- Galliou, Patrick; Jones, Michael (1991). The Bretons. Oxford: Blackwells. ISBN 978-0-631-16406-7.

- Jones, Michael (1988). The Creation of Brittany: A Late Medieval State. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-0-907628-80-4.

- Leach, Daniel (August 2010). "'A sense of Nordism': the impact of Germanic assistance upon the militant interwar Breton nationalist movement". European Review of History. 17 (4): 629–646. doi:10.1080/13507481003743559. S2CID 153659806.

- Nicolas, Michel (2007). Histoire de la revendication bretonne, ou la revanche de la démocratie locale sur le "démocratisme": des origines jusqu'aux années 1980. Bibliophiles de Bretagne (in French). Vol. 4. Breizh. ISBN 978-2-84346-312-9.

- Nicolas, Michel (2012). Breizh, la Bretagne revendiquée : des années 1980 à nos jours. Morlaix: Skol Vreizh. ISBN 978-2-915623-81-9.

- Price, Neil (1989). The Vikings in Brittany. Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London. ISBN 978-0-903521-22-2.

- O'Callaghan, Michael (1982). "Separatism in Brittany" (PDF). Durham University Thesis: 1–239. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Smith, Julia (1992). Province and Empire: Brittany and the Carolingians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38285-4.

.svg.png.webp)