British Somaliland

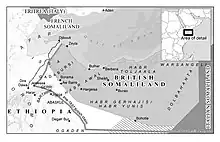

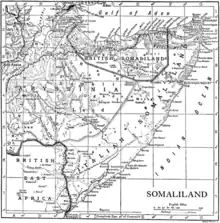

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate (Somali: Dhulka Maxmiyada Soomaalida ee Biritishka), was a crown colony and protectorate of the United Kingdom in modern Somaliland.[2] During its existence, the territory was bordered by Italian Somalia, French Somali Coast and Abyssinia (temporarily Italian Ethiopia). From 1940 to 1941, it was occupied by the Italians and was part of Italian East Africa.

Somaliland Protectorate | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884–1940 1941–1960 | |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Badge of British Somaliland (1952-1960)

| |||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: God Save the Queen (1862–1901 & 1952–1960) God Save the King (1901–1940 & 1941–1952) | |||||||||||||||||

British Somaliland in 1922 | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Self-ruling sultanates under British Protection (administered by the Government of India until 1 October 1898)

| ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Berbera (until 1941) Hargeisa (from 1941) | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Somali, Arabic, English | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1884–1888 (first) | Frederick Mercer Hunter | ||||||||||||||||

• 1959–1960 (last) | Douglas Hall | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• British control | 1884 | ||||||||||||||||

• Protection treaties | 1886 | ||||||||||||||||

• Somali coast protectorate | 20 July 1887 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1900–1920 | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 August 1940 | |||||||||||||||||

| 8 April 1941 | |||||||||||||||||

| 26 June 1960 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 July 1960 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1904[1] | 137,270 km2 (53,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1904[1] | 153,018 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Rupee (1884–1941) East African shilling (1941–1962) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Somaliland | ||||||||||||||||

| History of Somaliland |

|---|

|

|

|

On 26 June 1960, British Somaliland declared independence as the State of Somaliland. Five days later, on 1 July 1960, the State of Somaliland voluntarily united with the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) to form the Somali Republic.[3][4] The government of Somaliland, a self-declared sovereign state that is internationally recognised as an autonomous region of Somalia,[5][6] regards itself as the successor state to British Somaliland.[7][8]

History

Treaties and establishment

In the late 19th century, the United Kingdom signed agreements with the Gadabuursi, Issa, Habr Awal, Garhajis, Habr Je'lo and Warsangeli clans establishing a protectorate.[4][9][10] The British garrisoned the protectorate from Aden and administered it from their British India colony until 1898. British Somaliland was then administered by the Foreign Office until 1905 and afterwards by the Colonial Office.

Generally, the British did not have much interest in the resource-barren region.[11] The stated purposes of the establishment of the protectorate were to "secure a supply market, check the traffic in slaves, and to exclude the interference of foreign powers."[12] The British principally viewed the protectorate as a source for supplies of meat for their British Indian outpost in Aden through the maintenance of order in the coastal areas and protection of the caravan routes from the interior.[13] Hence, the region's nickname of "Aden's butcher's shop".[14] Colonial administration during this period did not extend administrative infrastructure beyond the coast,[15] and contrasted with the more interventionist colonial experience of Italian Somalia.[16]

Dervish uprising

Beginning in 1899, the British were forced to expend considerable human and military capital to contain a decades-long resistance movement mounted by the Dervish resistance movement.[17] The movement was led by Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, a Somali religious leader referred to colloquially by the British as the "Mad Mullah".[18] Repeated military expeditions were unsuccessfully launched against Hassan and his Dervishes before World War I.

On 9 August 1913, the Somaliland Camel Constabulary suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Dul Madoba at the hands of the Dervishes. Hassan had already evaded several attempts to capture him. At Dul Madoba, his forces killed or wounded 57 members of the 110-man Constabulary unit, including the British commander, Colonel Richard Corfield.

In 1914, the British created the Somaliland Camel Corps to assist in maintaining order in British Somaliland.

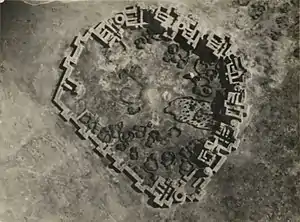

In 1920, the British launched their fifth and final expedition against Hassan and his followers. Employing the then-new technology of military aircraft, the British finally managed to quell Hassan's twenty-year-long struggle. The British tricked Hassan into preparing for an official visit, then launched bombing raids in the city of Taleh where most of his troops were stationed, causing the mullah to retreat into the desert.[19] Hassan and his Dervish supporters fled to the Ogaden, where Hassan died in 1921.[20]

Somaliland Camel Corps

The Somaliland Camel Corps, also referred to as the Somali Camel Corps, was a unit of the British Army based in British Somaliland. It lasted from the early 20th century until 1944. The troopers of the Somaliland Camel Corps had a distinctive dress. It was based on the standard British Army khaki drill but included a knitted woollen pullover and drill patches on the shoulders. Shorts were worn with woollen socks on puttees and "chaplis", boots or bare feet. Equipment consisted of leather ammunition bandolier and a leather waist belt. The officers wore pith helmets and khaki drill uniforms. Other ranks wore a "kullah" with "puggree" which ended in a long tail which hung down the back.[21] A "chaplis" is typically a colourful sandal. A "kullah" is a type of cap. A "puggree" is typically a strip of cloth wound around the upper portion of a hat or helmet, particularly a pith helmet, and falling down from behind to act as a shade for the back of the neck.

British Somaliland 1920–1930

Following the defeat of the Dervish resistance, the two fundamental goals of British policy in British Somaliland were the preservation of stability and the economic self-sufficiency of the protectorate.[22] The second goal remained particularly elusive because of local resistance to taxation that might have been used to support the protectorate's administration.[23] By the 1930s, the British presence had extended to other parts of British Somaliland. Growth in commercial trade motivated some livestock herders to subsequently leave the pastoral economy and settle in urban areas.[24] Customs taxes also helped pay for British India's patrol of Somalia's Red Sea Coast.[25]

Among military units in British Somaliland during the interwar period was a battalion of the Indian Army 4th Bombay Grenadiers.[26]

Italian invasion

In August 1940, during the East African campaign in World War II, British Somaliland was invaded by Italy. The few British forces that were present attempted to defend the main road to Berbera, but were dislodged from their positions and retreated after losing the Battle of Tug Argan. During this period, the British rounded up soldiers and governmental officials to evacuate them from the territory through Berbera. In total, 7,000 people, including civilians, were evacuated.[27] The Somalis serving in the Somaliland Camel Corps were given the choice of evacuation or disbandment; the majority chose to remain and were allowed to retain their arms.[28]

In March 1941, after a six-month Italian occupation, British forces recaptured the protectorate during Operation Appearance. The final remnants of the Italian guerrilla movement discontinued all resistance in British Somaliland by the autumn of 1943.

1945 Sheikh Bashir rebellion

The 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion was an uprising by tribesmen of the Habr Je'lo clan in the cities of Burao and Erigavo in the former British Somaliland protectorate against British authorities in July 1945 led by Sheikh Bashir, a Somali religious leader belonging to the Yeesif sub-division.[29]

On 2 July, Sheikh Hamza collected 25 of his followers in the town of Wadamago and transported them on a lorry to the vicinity of Burao, where he distributed arms to half of his followers. On the evening of 3 July the group entered Burao and opened fire on the police guard of the central prison in the city, which was filled with prisoners arrested for previous demonstrations. The group also attacked the house of the district commissioner of Burao District, Major Chambers, resulting in the death of Major Chamber's police guard before escaping to Bur Dhab, a strategic mountain south-east of Burao, where Sheikh Bashir's small unit occupied a fort and took up a defensive position in anticipation of a British counterattack.[30]

The British campaign against Sheikh Hamza troops proved abortive after several defeats as his forces kept on the move. No sooner had the expedition left the area, than the news travelled fast among the Somali nomads across the plain. The war had exposed the British administration to humiliation. The government came to a conclusion that another expedition against him would be useless; that they must build a railway, make roads and effectively occupy the whole of the protectorate, or else abandon the interior. The latter course was decided upon and during the first months of 1945, the advance posts were withdrawn and the British administration confined to the coast town of Berbera.[31]

Sheikh Bashir settled many disputes among the tribes in the vicinity, which kept them from raiding each other. He was generally thought to settle disputes through the use of Islamic Sharia and gathered around him a strong following.[32]

Sheikh Bashir sent a message to religious figures in the town of Erigavo and called on them to revolt and join the rebellion he led. The religious leaders as well as the people of Erigavo heeded his call, and mobilized a substantial number of people armed with rifles and spears and staged a revolt. The British authorities responded rapidly and severely, sending reinforcements to the town and opening fire on the armed mobs in two "local actions" as well as arresting minor religious leaders in the town.[33]

The British administration recruited Indian and South African troops, led by police general James David, to fight against Sheikh Bashir and had intelligence plans to capture him alive. The British authorities mobilized a police force, and eventually on 7 July found Sheikh Bashir and his unit in defensive positions behind their fortifications in the mountains of Bur Dhab. After clashes Sheikh Bashir and his second-in-command, Alin Yusuf Ali, nicknamed Qaybdiid, were killed. A third rebel was wounded and was captured along with two other rebels. The rest fled the fortifications and dispersed. On the British side the police general leading the British troops as well as a number of Indian and South African troops perished in the clashes, and a policeman was injured.

Despite the death of Sheikh Hamza and his followers resistance against British authorities continued in Somaliland, especially in Erigavo where his death stirred further resistance in the town and the town of Badhan and lead to attacks on British colonial troops throughout the district and the seizing of arms from the rural constabulary.[34]

The British authorities was not finished with the rebels even after most of them had died and continued its counter-insurgency campaign. The authorities had quickly learned the names and identities of all the followers of Sheikh Bashir and tried to convince the locals to turn them in. When they refused, the authorities invoked the Collective Punishment Ordinance, under which the authorities seized and impounded a total of 6,000 camels owned by the Habr Je'lo, the clan that Sheikh Bashir belonged to. The British authorities made the return of the livestock dependent on the turning over and arrest of the escaped rebels.[35] The remaining rebels were subsequently found and arrested, and transported to the Saad-ud-Din archipelago, off the coast of Zeila in northwestern Somaliland.

Independence and union with the Trust Territory of Somaliland

In 1947, the entire budget for the administration of the British Somaliland protectorate was only £213,139.[25]

In May 1960, the British Government stated that it would be prepared to grant independence to the then Somaliland protectorate. The Legislative Council of British Somaliland passed a resolution in April 1960 requesting independence. The legislative councils of the territory agreed to this proposal.[37]

In April 1960, leaders of the two territories met in Mogadishu and agreed to form a unitary state. An elected president was to be head of state. Full executive powers would be held by a prime minister answerable to an elected National Assembly of 123 members representing the two territories.

On 26 June 1960, the British Somaliland protectorate gained independence as the State of Somaliland before uniting five days later with the Trust Territory of Somalia to form the Somali Republic (Somalia) on 1 July 1960.[3][4]

The legislature appointed the speaker Hagi Bashir Ismail Yousuf as first President of the Somali National Assembly and, the same day, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar become President of the Somali Republic.

Politics

Until 1898, Somaliland was administered by the British resident at Aden as a dependency of the Government of India. From 1898 it was under the purview of the Foreign Office, and from 1905 onward (with the exception of a period of military administration until 1948 following the Italian invasion) it was administered by the Colonial Office.

Until 1957, executive and legislative power were solely vested in the Governor, although he had a non-statutory council to advise him. In 1947, a Protectorate Advisory Council was established on a tribal basis, with representatives of other communities and official members as well. In 1957, a Legislative Council and an Executive Council were created. From 1959, there were elections to the Legislative Council. A new constitution was introduced in 1960, shortly before independence.

Somaliland

In 1991, after a bloody civil war for independence in the northern part of Somali Democratic Republic, the area which formerly encompassed British Somaliland declared independence. In May 1991, the formation of the "Republic of Somaliland" was proclaimed, with the local government regarding it as the successor to the former British Somaliland as well as to the State of Somaliland. However, the Somaliland region's self-declared independence remains unrecognised by any country.[38]

Postage stamps

References

- "Census of the British empire. 1901". Openlibrary.org. 1906. p. 178. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- Kingdom, United. "Somaliland Protectorate, communicated by the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland". Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- "Somalia". Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–384.

- Lacey, Marc (5 June 2006). "The Signs Say Somaliland, but the World Says Somalia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "The Transitional Federal Charter of the Somali Republic" (PDF). University of Pretoria. 1 February 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2010. "The Somali Republic shall have the following boundaries. (a) North; Gulf of Aden. (b) North West; Djibouti. (c) West; Ethiopia. (d) South south-west; Kenya. (e) East; Indian Ocean."

- "Somaliland Marks Independence After 73 Years of British Rule" (fee required). The New York Times. 26 June 1960. p. 6. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- "How Britain said farewell to its Empire". BBC News. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- Issa-Salwe, Abdisalam M. (1996). The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy. London: Haan Associates. pp. 34–35. ISBN 1-874209-91-X.

- Samatar, Abdi Ismail The State and Rural Transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884–1986, Madison: 1989, University of Wisconsin Press, p. 31

- Samatar p. 31

- Samatar, p. 32

- Samatar, Unhappy Masses and the Challenge of Political Islam in the Horn of Africa, Somalia Online Archived 3 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 10-03-27

- Samatar, The state and rural transformation in Northern Somaliap. 42

- McConnell, Tristan (15 January 2009). "The Invisible Country". Virginia Quarterly Review. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- Mohamoud, Abdullah A. (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557534132. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Jardine, Douglas James (15 October 2015). Mad Mullah of Somaliland. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 9781781519820.

- Ross, Sherwood. "How the United States Reversed Its Policy on Bombing Civilians". The Humanist. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Samatar, The state and rural transformation in Northern Somalia, p. 39

- Mollo, p. 139

- Samatar, p. 45

- Samatar, p. 46

- Samatar, pp. 52–53

- Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, Thomas P. "Ethiopia in World War II". A Country Study: Ethiopia. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 October 2004. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Sharma, Gautam (1990). Valour and sacrifice: famous regiments of the Indian Army. Allied Publishers. ISBN 81-7023-140-X, 75.

- Playfair (1954), p. 178

- Wavell, p. 2724 Archived 9 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Mohamed, Jama (1996). Constructing colonial hegemony in the Somaliland protectorate, 1941-1960 (Thesis thesis). Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- of Rodd, Lord Rennell (1948). British Military Administration in Africa 1941–1947. HMSO. p. 481.

- "Taariikhdii Halgamaa: Sheekh Bashiir Sh. Yuusuf. W/Q: Prof Yaxye Sheekh Caamir | Laashin iyo Hal-abuur". 11 January 2018. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Sheekh Caamir, Prof. Yaxye (11 January 2018). "Taariikhdii Halgamaa: Sheekh Bashiir Sh. Yuusuf". Laashin.

- of Rodd, Lord Rennell (1948). British Military Administration in Africa 1941–1947. HMSO. p. 482.

- Mohamed, Jama (2002). "'The Evils of Locust Bait': Popular Nationalism during the 1945 Anti-Locust Control Rebellion in Colonial Somaliland". Past & Present. 174 (174): 184–216. doi:10.1093/past/174.1.184. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 3600720. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Annual Colonial Office Report on the Somaliland Protectorate, 1948. p. 31.

- http://foto.archivalware.co.uk/data/Library2/pdf/1960-TS0044.pdf Archived 14 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Somali Independence Week Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Somali State Conflict: Revisiting the Political Economy of the Somali Security State (1969-1991)" (PDF). 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2020.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)