British Turks

British Turks (Turkish: Britanyalı Türkler) or Turks in the United Kingdom (Turkish: Birleşik Krallık'taki Türkler) are Turkish people who have immigrated to the United Kingdom. However, the term may also refer to British-born persons who have Turkish parents or who have a Turkish ancestral background.

British Turks protesting in Central London. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Turkish-born residentsa 101,721 (2011 UK Census)[1] 72,000 (2009 ONS estimate) 150,000 (academic estimates) Turkish Cypriot-born residentsa 100,000–150,000 (academic estimates) Total populationb 500,000 (2011 Home Office estimate)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| London (Camden, Croydon, Enfield, Euston, Hackney Haringey, Islington, Kensington, Lambeth, Lewisham, Palmers Green, Seven Sisters, Southwark, Waltham Forest, and Wood Green) | |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam (including practising and non-practising) Minority Shia Islam (Alevi and Twelver), other religions, or irreligious | |

a Official data regarding the British Turkish community excludes British-born and dual heritage children of Turkish origin.[3] b This includes 150,000 Turkish nationals, 300,000 Turkish Cypriots, and also smaller Turkish minorities such as Bulgarian Turks and Romanian Turks.[4] |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| British people |

|---|

| United Kingdom |

| Eastern European |

| Northern European |

| Southern European |

| Western European |

| Central Asian |

| East Asian |

| South Asian |

| Southeast Asian |

| West Asian |

| African and Afro-Caribbean |

| Northern American |

| Latin American |

Turks first began to emigrate in large numbers from the island of Cyprus for work and then again when Turkish Cypriots were forced to leave their homes during the Cyprus conflict. Turks then began to come from Turkey for economic reasons. Recently, smaller groups of Turks have begun to immigrate to the United Kingdom from other European countries.[5]

As of 2011, there was a total of about 500,000 people of Turkish origin in the UK,[6] made up of approximately 150,000 Turkish nationals and about 300,000 Turkish Cypriots.[4] Furthermore, in recent years, there has been a growing number of ethnic Turks immigrating to the United Kingdom from Algeria and Germany. Many other Turks have immigrated to Britain from parts of the southern Balkans where they form an ethnic and religious minority dating to the early Ottoman period, particularly Bulgaria, Romania, the Republic of North Macedonia, and the province of East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece.[4][7]

History

Ottoman migration

The first Turks settled in the United Kingdom during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[8][9] Between the years 1509-1547 Turks were counted among Henry VIII's mercenary troops as the Tudor monarch was known to make heavy use of foreign troops.[10] By the late sixteenth century hundreds of Turks were to be found in England who were freed from galley slavery on Spanish ships by English pirates.[8] It is believed that the release of Turkish slaves from Spanish ships were for political reasons.[8] At the time, England was vulnerable to attacks from the Spanish empire, and Queen Elizabeth I wanted to cultivate good relations with the Ottoman Empire as a means of resisting the Spanish military. The Turkish slaves who had not yet returned to the Ottoman Empire requested assistance from London merchants trading in North Africa during the times of war between England and Spain, or England and France. Those who decided not to return to their country converted to Christianity and settled in England.[11]

The first ever documented Muslim who arrived in England was in the mid-1580s, is believed to be a Turk born in Negropont.[12] He was captured by William Hawkins aboard a Spanish ship and brought to England.[12] The Turk was known as Chinano, assumed to come from the name Sinan, and converted to Anglicanism in October 1586.[12] Once baptised, he was given the Christian name of William.[13] Two decades later, an allowance of 6 pence per diem was paid to a Turkish captive who embraced Christianity in England and assumed the name John Baptista.[13][10] Between the years 1624-1628 Salleman Alexander, ‘Richard a poore Turk’ and another unnamed Turk were also baptized in London.[13] Thus, by 1627, there were close to 40 Muslims living in London alone, most of which were Turks.[14] One of the most famous Muslim converts to Christianity was Iusuf (Yusuf), ‘the Turkish Chaous’ (çavuş), who was born in Constantinople. Baptised on 30 January 1658, his conversion is deemed significant because Iusuf served as an ambassador for the Ottoman Sultan.[13]

By the early 1650s, an English merchant who had been trading in the Ottoman Empire returned to London with a Turkish servant who introduced the making of Turkish coffee, and by 1652 the first coffee house had opened in London; within a decade, more than 80 establishments flourished in the city.[14] In 1659, Yusuf, an Ottoman administrator from Negropont, was baptized in England and took the name Richard Christophilus.[10] With the influx of Muslim merchants and diplomats into England due to improved Anglo-Ottoman relations, a race for Muslim converts began between the Cromwellian party and the Anglicans.[10] By 1679, Britain saw its first ever Turkish bath opened in London.[9] Once George I became King of England in 1714, he took with him from Hanover his two Turkish protégés, Mustafa and Mehmet. Mehmet's mother and Mustafa's son would also reside in England.[10] Due to their prominence in the court, Mustafa and Mehmet were depicted in the murals of Kensington Palace. In 1716 King George I ennobled Mehmet, who adopted the surname von Königstreu (true to the king).[10]

Ottoman Turkish migration continued after the Anglo-Ottoman Treaty of 1799.[15] In the years 1820–22, the Ottoman Empire exported goods worth £650,000 to the United Kingdom. By 1836–38, that figure had reached £1,729,000 with many Ottoman merchants entering the country.[16] In 1839, the Ottoman Tanzimat reform movement began. This period saw rapid changes in Ottoman administration including numerous high-ranking officials receiving their higher education and postings in the Western nations. Rashid Pasha (1800–1858) served as the Ottoman ambassador to Paris and London in the 1830s. One of his disciples and future grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire, Ali Pasha (1815–1871), also served as ambassador to London in the 1840s. Fuad Pasha (1815–1869), also received appointment at the Ottoman London embassy before rising in public office in his own nation.[10]

In 1865 Ottoman intellectuals had established the Young Ottomans organisation in order to resist the absolutism of Abdulaziz.[17] Many of these intellectuals escaped to London (and to Paris) in June 1867 where they were able to freely express their views by criticising the Ottoman regime in newspapers.[17] Their successors, the Young Turks, also took refuge in London in order to escape the absolutism of Abdul Hamid II. Even more political refugees were to arrive after the Young Turk Revolution of July 1908 and after the First World War.[17]

Turkish Cypriot migration

Migration from Cyprus to the United Kingdom began in the early 1920s when the British annexed Cyprus in 1914 and the residents of Cyprus became subjects of the Crown.[18] Many Turkish Cypriots went to the United Kingdom as students and tourists whilst others left the island due to the harsh economic and political life on the island leading to lack of job opportunities.[17] Turkish Cypriot emigration to the United Kingdom continued to increase when the Great Depression of 1929 brought economic depression to Cyprus, with unemployment and low wages being a significant issue.[19][20] During the Second World War, the number of Turkish run cafes increased from 20 in 1939 to 200 in 1945 which created a demand for more Turkish Cypriot workers.[21] Thus, throughout the 1950s, Turkish Cypriots began to emigrate to the United Kingdom for economic reasons and by 1958 the number of Turkish Cypriots was estimated to be 8,500.[22] Their numbers increased each year as rumours about immigration restrictions appeared in much of the Cypriot media.[20]

As the island of Cyprus' independence was approaching, Turkish Cypriots felt vulnerable as they had cause for concern about the political future of the island.[21] This was first evident when Greek Cypriots held a referendum in 1950 in which 95.7% of eligible Greek Cypriot voters cast their ballots in supporting a fight aimed at uniting Cyprus with Greece.[23] Thus, the 1950s saw the arrival of many Turkish Cypriots to the United Kingdom who were fleeing the EOKA terrorists and its aim of Enosis.[17] Once Cyprus became an independent state in 1960, inter-ethnic fighting broke out in 1963, and by 1964 some 25,000 Turkish Cypriots became internally displaced, accounting to about a fifth of their population.[24][25] Thus, the oppression which the Turkish Cypriots suffered during the mid-1960s led to many of them emigrating to the United Kingdom.[17] Furthermore, Turkish Cypriots continued to emigrate to the United Kingdom during this time due to the economic gap which was widening in Cyprus. The Greek Cypriots were increasingly taking control of the country's major institutions causing the Turkish Cypriots to become economically disadvantaged.[21] Thus, the political and economic unrest in Cyprus after 1964 sharply increased the number of Turkish Cypriot immigrants to the United Kingdom.[20]

Many of these early migrants worked in the clothing industry in London, where both men and women could work together- sewing was a skill which the community had already acquired in Cyprus.[26] Turkish Cypriots were concentrated mainly in the north-east of London and specialised in the heavy-wear sector, such as coats and tailored garments.[27][28] This sector offered work opportunities where poor knowledge of the English language was not a problem and where self-employment was a possibility.[29]

By the late 1960s, approximately 60,000 Turkish Cypriots were forcefully moved into enclaves in Cyprus.[30] Evidently, this period in Cypriot history resulted in an exodus of more Turkish Cypriots. The overwhelming majority migrated to the United Kingdom, whilst others went to Turkey, North America and Australia.[31] Once the Greek military junta rose to power in 1967, they staged a coup d'état in 1974 against the Cypriot President, with the help of EOKA B, to unite the island with Greece.[32] This led to a military offensive by Turkey who divided the island.[25] By 1983, the Turkish Cypriots declared their own state, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which has since remained internationally unrecognised except by Turkey. The division of the island led to an economic embargo against the Turkish Cypriots by the Greek Cypriot controlled Government of Cyprus. This had the effect of depriving the Turkish Cypriots of foreign investment, aid and export markets; thus, it caused the Turkish Cypriot economy to remain stagnant and undeveloped.[33] Due to these economic and political issues, an estimated 130,000 Turkish Cypriots have emigrated from Northern Cyprus since its establishment to the United Kingdom.[34][35]

Many Turkish Cypriots emigrated to the United Kingdom with their extended families and/or brought their parents over shortly after their arrival to prevent the breakup of the family unit. These parents played a valuable role in giving support at home by looking after their grandchildren, whilst their children were working. The majority of these people are now of pensionable age, with little English language skills, given their lack of formal education and their insulation within the Turkish Cypriot community.

Finally, there is a small third group of settlers who came to the UK for educational purposes, and who then settled, in some cases being ‘overstayers’ and took up professional posts. Many of these people, as well as the second and third generation educated descendants of earlier settlers, are the initiators of the voluntary groups and organisations, which give support and advice to Turkish speaking people living in England – mainly in London and the surrounding areas.

Mainland Turkish migration

Migration from the Republic of Turkey to the United Kingdom began when migrant workers arrived during the 1970s and were then followed by their families during the late 1970s and 1980s.[36] Many of these workers were recruited by Turkish Cypriots who had already established businesses such as restaurants.[20] These workers were required to renew their work permits every year until they became residents after living in the country for five years.[36] The majority who entered the United Kingdom in the 1970s were mainly from rural areas of Turkey. However, in the 1980s, intellectuals, including students, and highly educated professionals arrived in the United Kingdom, most of which received support from the Turkish Cypriot community.[37] Mainland Turks settled in similar areas of London in which the Turkish Cypriots lived in; however, many have also moved to the outer districts such as Enfield and Essex.[36]

Migration from other countries

More recently, ethnic Turks from traditional areas of Turkish settlement, especially from Europe, have emigrated to the United Kingdom.[5] There is a growing number of Algerian Turks,[38] Bulgarian Turks,[4] Macedonian Turks, Romanian Turks[4] and Western Thrace Turks from the province of East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece now residing in the United Kingdom.[7] Furthermore, there is also an increasing number of Turkish families arriving from German-speaking countries (especially German Turks and Dutch Turks).[39]

Demographics

Population

There is an estimated 500,000 people of Turkish origin living in the United Kingdom.[6][40][41][42][43][44] The Turkish community is made up of about 300,000 Turkish Cypriots, 150,000 Turkish nationals, and smaller groups of Bulgarian Turks, Macedonian Turks, Romanian Turks and Western Thrace Turks.[2][7][45] There is also an increasing number of Turks arriving from German-speaking countries (mainly German Turks and Dutch Turks).[39]

Turkish Cypriot population

Between 100,000 and 150,000 Turkish Cypriots have immigrated to the United Kingdom.[46][47] According to the Department for Communities and Local Government and the Turkish consulate, 130,000 nationals of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus have immigrated to the United Kingdom; however, this does not include Turkish Cypriots who have emigrated from the Republic of Cyprus or British-born Turkish Cypriots.[3][48] In May 2001, the TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that about 200,000 Turkish Cypriots were living in the United Kingdom.[49] In 2011, the Home Affairs Committee stated that there are now 300,000 Turkish Cypriots living in the United Kingdom.[4] The "Kıbrıs Gazetesi", in 2008, claimed that 280,000 Turkish Cypriots were living in London alone.[50] Furthermore, an article by Armin Laschet suggests that the British-Turkish Cypriot community now numbers 350,000[40] whilst some Turkish Cypriot sources suggest that they have a total population of 400,000 living in the United Kingdom.[51][52]

Mainland Turkish population

According to the Office for National Statistics, the estimated number of British residents born in Turkey was 72,000 in 2009,[53] compared to the 54,079 recorded by the 2001 UK Census.[54] The Home Office and the Turkish consulate in London both claim that there are approximately 150,000 Turkish nationals living in the United Kingdom.[2][48] Academic sources suggest that the Turkey-born population is made up of 60,000 to 100,000 ethnic Turks and 25,000 to 50,000 ethnic Kurds.[55] However, the Department for Communities and Local Government suggests that the Kurdish community in the UK is about 50,000, among which Iraqi Kurds make up the largest group, exceeding the numbers from Turkey and Iran.[56] The Atatürk Thought Association claims that 300,000 people of Turkish origin (not including Turkish Cypriots) are living in the UK.[7] By 2005, The Independent newspaper reported that one gang alone had illegally smuggled up to 100,000 Turks into the UK.[57] In 2011, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ahmet Davutoğlu, claimed that there were almost 400,000 Turkish citizens living in the United Kingdom.[58]

Other Turkish populations

There is a growing number of Turks from countries other than Cyprus and Turkey who have emigrated to the United Kingdom, mainly from Algeria, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Macedonia and Romania. These populations, which have different nationalities (i.e. Algerian, Bulgarian, German, Greek, Macedonian or Romanian citizenship), share the same ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious origins as the Turks and Turkish Cypriots and are thus part of the Turkish-speaking community of the United Kingdom.

Bulgarian Turks

In 2009 the Office for National Statistics estimated that 35,000 Bulgarian-born people were resident in the UK.[59] According to the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria, Bulgarian Turks make up 12% of short term migration, 13% of long term migration, and 12% of the labour migration.[60] However, the number of Bulgarian Turks in the United Kingdom may be much higher; Bulgarian citizens of Turkish origin make up entire majorities in some countries.[61] For example, in the Netherlands Bulgarian Turks make up about 80% of Bulgarian citizens.[62]

Western Thrace Turks

The total number of Turkish-speaking Muslims who have emigrated from Western Thrace, that is, the province of East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece is unknown; however, it is estimated that 600-700 Western Thrace Turks are living in London. The number of Western Thrace Turks, as well as Pomaks from Northern Greece, living outside London or who are British-born is unknown.[63] On 15 January 1990 the Association of Western Thrace Turks UK was established.[64]

Settlement

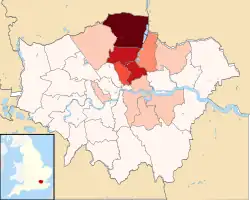

The vast majority of Turkish-born people recorded in the 2001 British census lived in England, with only 471 recorded in Wales and 1,042 in Scotland. A total of 39,132 Turkish-born people were recorded in London.[65] The 2001 census also shows that the Cyprus-born population (which includes both Turkish and Greek Cypriots) live in similar areas to the Turkish-born population.[66] The majority live in England, with only 1,001 in Wales, and 1,533 in Scotland. A total of 45,887 were recorded in London.[66] However, official data regarding the British Turkish community excludes British-born and dual heritage children of Turkish origin; thus, it is unlikely that any of the official figures available provide a true indication of the community.[3]

Turks from the same villages and districts from their homeland tend to congregate in the same quarters in the UK.[67] Many of the Turkish-speaking communities have successfully settled in different parts of the capital,[67] notably in Hackney and Haringey, but also in Enfield, Lewisham, Lambeth, Southwark, Croydon, Islington, Kensington, Waltham Forest, and Wood Green.[3] The majority of the Turkish population live in Hackney, and they are mainly Turkish Cypriot. Turkish-speaking communities are located in all parts of the Borough, though there is a greater concentration in North and Central parts of the Borough. Stoke Newington, Newington Green and Dalston have the greatest concentration of population and in particular along Green Lanes, running from Manor House down to Newington Green Roundabout.[68]

According to the Department for Communities and Local Government, outside London there are smaller Turkish communities in Birmingham, Hertfordshire, Luton, Manchester, Sheffield and the East Midlands.[3] At the time of the 2001 census, only two census tracts outside London were home to more than 100 Turkish-born residents: south Cheshunt in Hertfordshire and Clifton in Nottingham.[65] As for the Cypriot-born residents, two areas of Manchester – Stretford and Moss Side – have the largest Cyprus-born (regardless of ethnicity) clusters outside London.[66]

Culture

Traditional family values are considered to be very important for the Turkish community.[69] Marriage in particular is seen as an important part of their social sphere, and considerable social pressure is put onto single Turks to get married.[69] Thus, getting married and having a family is a significant part of their Turkish identity.[69] Turkish parents consistently try to hold onto the cultural values in order to 'protect' these traditional values onto the younger generation.[70] Young Turks from a very young age are encouraged to attend Turkish school to learn about the Turkish culture including folk dances, food, history and the language.[5] The first generation generally maintains their culture rather than adopting the British social and cultural values. However, the younger generations have a desire to preserve parental values at home and to adopt some elements of the host culture outside the home.[71]

Language

The Turkish language is the main language spoken among the community in the United Kingdom, but a Turkish Cypriot dialect is also widely spoken amongst its community. The first generation and recent migrants often speak fluent Turkish and women within the community are particularly constrained by language limitations.[72][73]

A new Turkish language, Anglo-Turkish or also referred to as Turklish, has been forming amongst the second and third generations, where the English language and the Turkish language is used interchangeably in the same sentences.[72]

Religion

The vast majority of the Turkish community are Sunni Muslims, whilst the remaining people generally do not have any religious affiliation. Nonetheless, even those who define themselves as not being religious feel that Islam has had an influence of their Turkish identity.[74] There is mostly a lack of knowledge about the basic principles of Islam within the younger generations.[71] The young generation of the community tends to have little knowledge about their religion and generally do not fulfill all religious duties.[71] However, the majority of young Turks still believe in Islam and the basic principles of the religion as it has more of a symbolic attachment to them due to traditional Turkish values.[71]

In recent years there has also been a strong movement towards religion by the community with the growth of Islamic organisations.[74] The desire to retain an identity has increased the strength of Islam among the communities. Clinging to traditions is seen as a way of maintaining culture and identity.[75] Nonetheless, young Turkish Muslims are brought up in a more liberal home environment than other British Muslims.[76] Thus, there are many Turks, especially the younger generations, who do not abstain from eating non-halal food or drinking alcohol, whilst still identifying as Muslim.[71]

The establishment of mosques has always been considered a priority within the Turkish community.[77] The first Turkish mosque, Shacklewell Lane Mosque, was established by the Turkish Cypriot community in 1977.[78] There are numerous other Turkish Mosques in London, mainly in Hackney, that are predominantly used by the Turkish community, especially the Aziziye Mosque[79] and Suleymaniye Mosque.[80] Notable Turkish mosques outside London include Selimiye Mosque in Manchester, Hamidiye Mosque in Leicester, and Osmaniye Mosque in Stoke-on-Trent.[81] During the Turkish invasion into Syria in 2019, adherents prayed for the Turkish army in a mosque under the guidance of the Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs.[82] As of 2018 there were 17 mosques under the control of the Directorate of Religious affairs.[83]

Activities are held in many Turkish mosques in order to retain an Islamic identity and to pass these traditional values onto the younger generation. These mosques have introduced new policies and strategies within their establishments as they have recognised that traditional methods are not very productive within the British context.[77] For example, one mosque has opened an independent primary school whilst another has been granted permission to register weddings in its mosque. Other mosques have even allowed the formation of small market places.[77]

Politics

Diplomatic missions

In 1793, Sultan Selim III established the first ever Ottoman Embassy in London with its first ambassador being Yusuf Ağa Efendi.[84] This marked the establishment of mutual diplomatic relations between the British and the Ottoman Turks. By 1834, a permanent embassy was established by Sultan Mahmud II.[85] Today the current Turkish Embassy is located at 43 Belgrave Square, London. There is also a Turkish Cypriot Embassy which represents nationals of Northern Cyprus located at 29 Bedford Square, London.

Cyprus issue

Due to the large Turkish Cypriot diaspora in the United Kingdom, the Cyprus dispute has become an important political issue in the United Kingdom. Turkish Cypriots carry out numerous activities such as lobbying in British politics.[86] Organisations were first set up during the 1950s and 1960s mainly by Turkish Cypriot students who had met and studied in cities in Turkey, such as Istanbul and Ankara, before moving to the United Kingdom.[87] Organisations such as the "Turkish Cypriot Association" were originally set up to preserve the communities culture and provide meeting places. However, during the 1960s, when political violence increased in Cyprus, these organisations centred more on politics.[88]

Turkish Cypriot organisations which engage in the Cyprus issue can be divided into two main groups: there are those who support the TRNC government, and those who oppose it. Both groups back up their lobbying by supporting British (and European) politicians.[87] The general impression is that the majority of British Turkish Cypriots are mainly conservative supporters of a Turkish Cypriot state and lobby for its recognition.[89] British Turkish Cypriots cannot vote in Cypriot elections; therefore, Turkish Cypriot organisations have tended to take an active role in political affairs by providing economic support for political parties.[90]

There are also campaigns which are directed at the wider British population and politicians. Yearly demonstrations occur to commemorate historical important days; for example, each year on 20 July, a pro-TRNC organisation arranges a demonstration from Trafalgar Square to the Turkish Embassy in Belgrave Square. 15 November is another date in which public places are used to voice political issues regarding the Cyprus dispute.[90]

Politicians

British political figures of Turkish descent include: Boris Johnson, who has served as Mayor of London, Foreign Secretary and was formerly the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and whose great-grandfather was Turkish (although he is of Circassian origin); Baroness Meral Hussein-Ece, the first woman of Turkish Cypriot origin to be a member of the House of Lords;[91] and Alp Mehmet, a diplomat who retired in 2009 as the British Ambassador to Iceland.[92]

Media

Turkish television programmes

- Euro Genc TV

Turkish magazines

- BritishTurks.com

- AdaAktüel Magazine

- BN Magazine

- T-VINE Magazine

Turkish newspapers

- Avrupa Gazete https://www.avrupagazete.co.uk/

- London Turkish Gazette

- Olay Gazetesi

Turkish radio

- Bizim FM

Turkish film

Notable people

See also

- List of British Turks

- Turks in London

- Turkey – United Kingdom relations

- Turks in Ireland

- Turks in Europe

- Britons in Turkey

- Byerley Turk

- Fordingbridge Turks football club, established in 1868 and named after Turks

Notes

- "Data Viewer - Nomis - Official Labour Market Statistics".

- Home Affairs Committee 2011, 38

- Communities and Local Government 2009a, 6

- Home Affairs Committee 2011, Ev 34

- Lytra & Baraç 2009, 60

- Travis, Alan (1 August 2011). "UK immigration analysis needed on Turkish legal migration, say MPs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Ingiltere Atatürkçü Düşünce Derneği. "İngiltere Atatürkçü Düşünce Derneği'nin tarihçesi, kuruluş nedenleri, amaçları". Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Gilliat-Ray 2010, 13

- Sonyel 2000, 146

- MuslimHeritage. "Muslims in Britain". Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- Matar 1998, 127

- Matar 2001, 261

- Matar 2001, 262

- Gilliat-Ray 2010, 14

- Cunningham & Ingram 1993, 105

- Pamuk 2010, 29

- Sonyel 2000, 147

- Yilmaz 2005, 153

- Hüssein 2007, 16

- Yilmaz 2005, 154

- Ansari 2004, 151

- Ansari 2004, 154

- Panteli 1990, 151

- Cassia 2007, 236

- Kliot 2007, 59

- Bridgwood 1995, 34

- Panayiotopoulos & Dreef 2002, 52

- London Evening Standard. "Turkish and proud to be here". Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Strüder 2003, 12

- Tocci 2004, 53

- Hüssein 2007, 18

- Savvides 2004, 260

- Tocci 2004, 61

- BBC. "Turkish today by Viv Edwardss". Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Cassia 2007, 238

- Issa 2005, 8

- Thomson 2006, 19

- Communities and Local Government 2009c, 34.

- Essex County Council. "An Electronic Toolkit for Teachers: Turkish and Turkish Cypriot Pupils" (PDF). Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Laschet, Armin (17 September 2011). "İngiltere'deki Türkler". Hurriyet. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Çilingir 2010, 108

- Federation of Turkish Associations UK. "Short history of the Federation of Turkish Associations in UK". Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "Turkey". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Lords. 13 January 2011. col. 1540. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- "Implications for Justice and Home Affairs area of accession of Turkey to EU". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011.

- BBC. "Network Radio BBC Week 39: Wednesday 28 September 2011: Turkish Delight?". Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- "Turkish Cypriot London". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Laçiner 2008, 397

- "Turkish community in the UK". Consulate General for the Republic of Turkey in London. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs (May 2001). "Briefing Notes on the Cyprus Issue". Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Defence. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- Cemal, Akay (6 September 2008). "Bir plastik sandalyeyi bile çok gördüler!." Kıbrıs Gazetesi. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Akben, Gözde (11 February 2010). "Olmalı mı Olmamalı mı?". Star Kıbrıs. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Cemal, Akay (2 June 2011). "Dıştaki gençlerin askerlik sorunu çözülmedikçe…". Kıbrıs Gazetesi. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Laçiner 2008, 397

- Communities and Local Government 2009b, 35

- Bennetto, Jason (12 October 2005). "Gang held over smuggling 100,000 Turks into Britain". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Turkish Weekly (31 March 2011). "Turkey's Foreign Minister Says Turkey and Britain have Bright Future". Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- Ivanov 2007, 58

- Markova 2010, 214

- Guentcheva, Kabakchieva & Kolarski 2003, 44.

- Şentürk 2008, 427.

- Association of Western Thrace Turks UK. "İngiltere Batı Trakya Türkleri Dayanışma Derneği 20. yılını kutladı". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "Turkey". Born Abroad. BBC. 7 September 2005. Archived from the original on 18 December 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Cyprus". Born Abroad. BBC. 7 September 2005. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Yilmaz 2005, 155.

- "Turkish London". BBC London. August 2008. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Küçükcan 2004, 249

- Küçükcan 2004, 250

- Küçükcan 2004, 251

- Communities and Local Government 2009a, 7

- Abu-Haidar 1996, 122

- Küçükcan 2004, 253

- THE TURKISH CYPRIOT COMMUNITY LIVING IN HACKNEY Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Ansari 2002, 13

- Küçükcan 2004, 254

- Geaves 2001, 218

- London Borough of Hackney. "UK Turkish Islamic Association - Aziziye Mosque". Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- London Borough of Hackney. "UK Turkish Islamic Cultural Centre / Suleymaniye Mosque". Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Çoştu & Turan 2009, 45

- Kurt, Mehmet (March 2022). "Spreading whose word? Militarism and nationalism in the transnational Turkish mosques". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 12 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1086/719164. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- Hazir, Agah (20 June 2019). "The Turkish Diyanet in the UK: How national conditions affect the influence of a transnational religious institution". London School of Economics. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- Aksan 2007, 226

- Quataert 2000, 80

- Østergaard-Nielsen 2003, 685

- Østergaard-Nielsen 2003, 688

- Østergaard-Nielsen 2003, 687

- Østergaard-Nielsen 2003, 690

- Østergaard-Nielsen 2003, 692

- Liberal Democrat Voice. "Baroness Meral Hussein-Ece's maiden speech". Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- "Alp Mehmet". Fipra International. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

References

- Abu-Haidar, Farida (1996), "Turkish as a Marker of Ethnic Identity and Religious Affiliation", in Suleiman, Yasir (ed.), Language and identity in the Middle East and North Africa, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-0410-1.

- Aksan, Virginia H. (2007), Ottoman Wars 1700-1870: An Empire Besieged, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-0-582-30807-7.

- Ansari, Humayun (2002), Muslims in Britain (PDF), Minority Rights Group International, ISBN 1-897693-64-8.

- Ansari, Humayun (2004), The infidel within: Muslims in Britain since 1800, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-685-2.

- Aksoy, Asu (2006), "Transnational Virtues and Cool Loyalties: Responses of Turkish-Speaking Migrants in London to 11 September" (PDF), Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Routledge, 32 (6): 923–946, doi:10.1080/13691830600761487, S2CID 216142054, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2012

- Atay, Tayfun (2010), "'Ethnicity within Ethnicity' among the Turkish-Speaking Immigrants in London", Insight Turkey, 12 (1): 123–138

- Bridgwood, Ann (1995), "Dancing the Jar: Girls' Dress and Turkish Cypriot Weddings", in Eicher, Joanne Bubolz (ed.), Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time, Berg Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85973-003-4.

- Canefe, Nergis (2002), "Markers of Turkish Cypriot History in the Diaspora: Power, visibility and identity", Rethinking History, 6 (1): 57–76, doi:10.1080/13642520110112119, OCLC 440918386, S2CID 143498169

- Cassia, Paul Sant (2007), Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-84545-228-5.

- Communities and Local Government (2009a), The Turkish and Turkish Cypriot Muslim Community in England: Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities (PDF), Communities and Local Government, ISBN 978-1-4098-1267-8, archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2010, retrieved 2 October 2010

- Communities and Local Government (2009b), The Iraqi Muslim Community in England: Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities (PDF), Communities and Local Government, ISBN 978-1-4098-1263-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2011, retrieved 31 October 2011

- Communities and Local Government (2009c), The Algerian Muslim Community in England: Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities (PDF), Communities and Local Government, ISBN 978-1-4098-1169-5, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2011.

- Çilingir, Sevgi (2010), "Identity and Integration among Turkish Sunni Muslims in Britain", Insight Turkey, 12 (1): 103–122

- Çoştu, Yakup; Turan, Süleyman (2009), "İngiltere'deki Türk Camileri ve Entegrasyon Sürecine Sosyo-Kültürel Katkıları" (PDF), Dinbilimleri Akademik Araştırma Dergisi, x (4): 35–52, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011

- Cunningham, Allan; Ingram, Edward (1993), Anglo-Ottoman encounters in the Age of Revolution, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-3494-4.

- Geaves, Ron (2001), "The Haqqani Naqshbandi: A Study of Apocalyptic Millennnialism within Islam", in Porter, Stanley E.; Hayes, Michael A.; Tombs, David (eds.), Faith in the Millennium, Sheffield Academic Press, ISBN 1-84127-092-X.

- Gilliat-Ray, Sophie (2010), Muslims in Britain: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53688-2.

- Guentcheva, Rossitza; Kabakchieva, Petya; Kolarski, Plamen (2003), Migrant Trends VOLUME I – Bulgaria: The social impact of seasonal migration (PDF), International Organization for Migration, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012, retrieved 24 April 2011

- Home Affairs Committee (2011), Implications for the Justice and Home Affairs area of the accession of Turkey to the European Union (PDF), The Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-215-56114-5

- Hüssein, Serkan (2007), Yesterday & Today: Turkish Cypriots of Australia, Serkan Hussein, ISBN 978-0-646-47783-1.

- Issa, Tözün (2005), Talking Turkey: the language, culture and identity of Turkish speaking children in Britain, Trentham Books, ISBN 978-1-85856-318-3.

- Ivanov, Zhivko (2007), "Economic Satisfaction and Nostalgic Laments: The Language of Bulgarian Economic Migrants After 1989 in Websites and Electronic Fora", in Gupta, Suman; Omoniyi, Tope (eds.), The Cultures of Economic Migration: International Perspectives, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-7070-4.

- Kliot, Nurit (2007), "Resettlement of Refugees in Finland and Cyprus: A Comparative Analysis and Possible Lessons for Israel", in Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (eds.), Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-0-7391-1607-4.

- Küçükcan, Talip (2004), "The making of Turkish-Muslim diaspora in Britain: religious collective identity in a multicultural public sphere" (PDF), Journal of Minority Muslim Affairs, 24 (2): 243–258, doi:10.1080/1360200042000296645, S2CID 143598673, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2010

- Laçiner, Sedat (2008), Ermeni sorunu, diaspora ve Türk dış politikası: Ermeni iddiaları Türkiye'nin dünya ile ilişkilerini nasıl etkiliyor?, USAK Books, ISBN 978-6054030071.

- Lytra, Vally; Baraç, Taşkın (2009), "Multilingual practices and identity negotiations among Turkish-speaking young people in a diasporic context", in Stenström, Anna-Brita; Jørgensen, Annette Myre (eds.), Youngspeak in a Multilingual Perspective, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 978-90-272-5429-0.

- Markova, Eugenia (2010), "Optimising migration effects: A perspective from Bulgaria", in Black, Richard; Engbersen, Godfried; Okolski, Marek; et al. (eds.), A Continent Moving West?: EU Enlargement and Labour Migration from Central and Eastern Europe, Amsterdam University Press, ISBN 978-90-8964-156-4.

- Matar, Nabil (1998), Islam in Britain, 1558-1685, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-62233-2.

- Matar, Nabil (2001), "The First Turks and Moors in England", in Vigne, Randolph; Littleton, Charles (eds.), From Strangers to Citizens: The Integration of Immigrant Communities in Britain, Ireland, and colonial America, 1550-1750, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-902210-86-7.

- Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva (2003), "The democratic deficit of diaspora politics: Turkish Cypriots in Britain and the Cyprus issue", Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 29 (4): 683–700, doi:10.1080/1369183032000123459, S2CID 145528555

- Pamuk, Allan (2010), The Ottoman Empire and European Capitalism 1820-1913, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-13092-9.

- Panteli, Stavros (1990), The making of modern Cyprus: from obscurity to statehood, CInterworld Publications, ISBN 978-0-948853-09-8.

- Panayiotopoulos, Prodromos; Dreef, Marja (2002), "London: Economic Differentiation and Policy Making", in Rath, Jan (ed.), Unravelling the rag trade: immigrant entrepreneurship in seven world cities, Berg Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85973-423-0.

- Quataert, Donald (2000), The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-63328-1.

- Savvides, Philippos K (2004), "Partition Revisited: The International Dimension and the Case of Cyprus", in Danopoulos, Constantine Panos; Vajpeyi, Dhirendra K.; Bar-Or, Amir (eds.), Civil-military relations, nation building, and national identity: comparative perspectives, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-97923-2.

- Sirkeci, Ibrahim; Bilecen, Tuncay (2016), Little Turkey in Great Britain, London: Transnational Press London, ISBN 978-1-910781-19-7.

- Şentürk, Cem (2008), "West Thrace Turkish's Immigration to Europe" (PDF), The Journal of International Social Research, 1/2 (Winter 2008): 419–433

- Sonyel, Salahi R. (2000), "Turkish Migrants in Europe" (PDF), Perceptions, Center for Strategic Research, 5 (Sept.-Nov. 00): 146–153, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2013

- Strüder, Inge R. (2003), Do concepts of ethnic economies explain existing minority enterprises? The Turkish speaking economies in London (PDF), London School of Economics, ISBN 0-7530-1727-X

- Thomson, Mark (2006), Immigration to the UK: The case of Turks (PDF), University of Sussex: Sussex Centre for Migration Research

- Tocci, Nathalie (2004), EU accession dynamics and conflict resolution: catalysing peace or consolidating partition in Cyprus?, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-4310-4.

- Yilmaz, Ihsan (2005), Muslim Laws, Politics and Society in Modern Nation States: Dynamic Legal Pluralisms in England, Turkey and Pakistan, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-4389-0.

Further reading

- Enneli, Pinar; Modood, Tariq; Bradley, Harriet (2005), Young Turks and Kurds: A set of 'invisible' disadvantaged groups (PDF), York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation/University of Bristol, ISBN 978-1-85935-273-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008, retrieved 17 February 2008

- Erdemir, Aykan; Vasta, Ellie (2007), "Differentiating irregularity and solidarity: Turkish Immigrants at work in London" (PDF), COMPAS Working Paper, ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, University of Oxford, 42, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011, retrieved 30 March 2010.

External links

- Turkish Consulate in London

- BritishTurks.com - Life in the UK and a guide for living in London