Byzantine–Arab wars (780–1180)

Between 780–1180, the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid & Fatimid caliphates in the regions of Iraq, Palestine, Syria, Anatolia and Southern Italy fought a series of wars for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. After a period of indecisive and slow border warfare, a string of almost unbroken Byzantine victories in the late 10th and early 11th centuries allowed three Byzantine Emperors, namely Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes and finally Basil II to recapture territory lost to the Muslim conquests in the 7th century Arab–Byzantine wars under the failing Heraclian Dynasty.[3]

| Byzantine–Arab Wars (780–1180) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine-Arab Wars | |||||||||

.PNG.webp) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Byzantine Empire Holy Roman Empire[1] Italian city-states Crusader states |

Abbasid Caliphate Fatimid Caliphate Uqaylids Hamdanids Emirate of Sicily Emirate of Crete | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Byzantine Emperors Strategoi of the Themata Drungaries of the Fleets |

Abbasid Caliphate Fatimid Caliphate rulers | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total Strength 80,000 in 773 Total Strength 100,000 in 1025 Total Strength 50,000 + militia in 1140 |

Abbasid Strength 100,000 in 781[2] Abbasid Strength 135,000 in 806[2] | ||||||||

Consequently, large parts of Syria,[3] excluding its capital city of Damascus, were taken by the Byzantines, even if only for a few years, with a new theme of Syria integrated into the expanding empire. In addition to the natural gains of land, and wealth and manpower received from these victories, the Byzantines also inflicted a psychological defeat on their opponents by recapturing territory deemed holy and important to Christendom, in particular the city of Antioch—allowing Byzantium to hold two of Christendoms' five most important Patriarchs, those making up the Pentarchy.[4]

Nonetheless, the Arabs remained a fierce opponent to the Byzantines and a temporary Fatimid recovery after c. 970 had the potential to reverse many of the earlier victories.[5] And while Byzantium took large parts of Palestine, Jerusalem was left untouched and the ideological victory from the campaign was not as great as it could have been had Byzantium recaptured this Patriarchal seat of Christendom. Byzantine attempts to stem the slow but successful Arab conquest of Sicily ended in a dismal failure.[6] Syria would cease to exist as a Byzantine province when the Turks took the city of Antioch in c. 1084. The Crusaders took the city back for Christendom in 1097 and established a Byzantine protectorate over the Crusader Kingdoms in Jerusalem and Antioch under Manuel I Komnenos.[7] The death of Manuel Komnenos in 1180 ended military campaigns far from Constantinople and after the Fourth Crusade both the Byzantines and the Arabs were engaged in other conflicts until they were conquered by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th and 16th centuries, respectively.

Background, 630–780

In 629, conflict between Byzantine Empire and Arabs started when both parties confronted in the Battle of Mu'tah. Having recently converted to Islam and unified by the Islamic Prophet's call for a Jihad (struggle) against the Byzantine and Persian Empires, they rapidly advanced and took advantage of the chaos of the Byzantine Empire, which had not fully consolidated its re-acquisitions from the Persian invasions in c. 620. By 642, the Empire had lost Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia.[8] Despite having lost two-thirds of its land and resources (most of all the grain supply of Egypt) the Empire nonetheless retained 80,000 troops, thanks to the efficiency of the Thema system and a reformed Byzantine economy aimed at supplying the army with weapons and food.[9] With these reforms, the Byzantines were able to inflict a number of defeats against the Arabs; twice at Constantinople in 674 and 717 and at Akroinon in 740.[10] Constantine V, the son of Leo III (who had led Byzantium to victory in 717 and 740) continued the successes of his father by launching a successful offensive that captured Theodosioupolis and Melitene. Nonetheless, these conquests were temporary; the Iconoclasm controversy, the ineffective rule of Irene and her successors coupled with the resurrection of the Western Roman Empire under the Frankish Carolingian Empire and Bulgarian invasions meant that the Byzantines were on the defensive again.

Period of 780–842

Michael II vs Caliph Al-Ma'mun

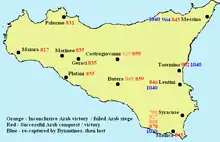

Between 780 and 824, the Arabs and the Byzantines were settled down into border skirmishing, with Arab raids into Anatolia replied in kind by Byzantine raids that "stole" Christian subjects of the Abbasid Caliphate and forcibly settled them into the Anatolian farmlands to increase the population (and hence provide more farmers and more soldiers). The situation changed however with the rise to power of Michael II in 820. Forced to deal with the rebel Thomas the Slav, Michael had few troops to spare against a small Arab invasion of 40 ships and 10,000 men against Crete, which fell in 824.[11] A Byzantine counter in 826 failed miserably. Worse still was the invasion of Sicily in 827 by Arabs of Tunis.[11] Even so, Byzantine resistance in Sicily was fierce and not without success whilst the Arabs became quickly plagued by the cancer of the Caliphate— internal squabbles. That year, the Arabs were expelled from Sicily but they were to return.

Theophilos vs Caliphs Al-Ma'mun and Al-Mu'tasim

In 829, Michael II died and was succeeded by his son Theophilos. Theophilos received a mixed diet of success and defeat against his Arab opponents. In 830 AD the Arabs returned to Sicily and after a year-long siege took Palermo from their Christian opponents and for the next 200 years they were to remain there to complete their conquest, which was never short of Christian counters.[12] The Abbasids meanwhile launched an invasion of Anatolia in 830 AD. Al-Ma'mun triumphed and a number of Byzantine forts were lost. Theophilos did not relent and in 831 captured Tarsus from the Muslims.[13] Defeat followed victory, with two Byzantine defeats in Cappadocia followed by the destruction of Melitene, Samosata and Zapetra by vengeful Byzantine troops in 837. Al-Mu'tasim however gained the upper hand with his 838 victories at Dazimon, Ancyra and finally at Amorium[13]—the sack of the latter is presumed to have caused great grief for Theophilos and was one of the factors of his death in 842.

Campaigns of Michael III, 842–867

Michael III was only two years of age when his father died. His mother, the Empress Theodora took over as regent. After the regency had finally removed Iconoclasm, war with the Saracens resumed. Although an expedition to recover Crete failed in 853, the Byzantine scored three major success in 853 and 855. A Byzantine fleet sailed unopposed in Damietta and set fire to all the ships in the harbour, returning with many prisoners.[14] Better still for Constantinople was the desperate and futile defense by the Emir of Melitene, whose realm was lost by the Arabs forever.[15] Insult was added to injury for the Arabs when the Arab governor of Armenia began losing control of his domain. After the 9th century, the Arabs would never be in a dominant position in the East.

In the West however, things went the Saracen way; Messina and Enna fell in 842 and 859 whilst Islamic success in Sicily encouraged the warriors of the Jihad to take Bari in 847, establishing the Emirate of Bari which would last to 871. In invading southern Italy, the Arabs attracted the attention of the Frankish powers north.

Michael III decided to remedy the situation by first taking back Crete from the Arabs. The island would provide an excellent base for operations in southern Italy and Sicily or at the least a supply base to allow the still resisting Byzantine troops to hold out. In 865 Bardas, maternal uncle to Michael III and one of the most prominent members of his regency, was set to launch an invasion when a potential plot against his wife by Basil I and Michael III (the former being the future emperor and favorite of the latter) was discovered. Thus Islamic Crete was spared from an invasion by Byzantium's greatest general at the time.[16]

Campaigns of Basil I and Leo VI, 867–912

Basil I

Like his murdered predecessor, the reign of Basil I saw a mixture of defeat and victory against the Arabs. Byzantine success in the Euphrates valley in the East was complemented with successes in the west where the Muslims were driven out of the Dalmatian coast in 873 and Bari fell to the Byzantines in 876.[17] However, Syracuse fell in 878 to the Sicilian Emirate and without further help Byzantine Sicily seemed lost.[17] In 880 Taranto and much of Calabria fell to Imperial troops. Calabria had been Rome's pre-Aegyptus bread basket, so this was more than just a propaganda victory.

Leo VI

Basil I died in 886, convinced that the future Leo VI the Wise was actually his illegitimate son by his mistress Eudokia Ingerina. The reign of Leo VI rendered poor results against the Arabs. The sack of Thessalonika in 904 by the Saracens of Crete was avenged when a Byzantine army and fleet smashed its way towards Tarsus and left the port, as important to the Arabs as Thessalonika was to Byzantium, in ashes.[18] The only other notable events included the loss of Taormina in 902 and a six-month siege of Crete. The expedition departed when news of the Emperor's death reached Himerios, commander of the expedition, and then it was almost completely destroyed (Himerios escaped) not far from Constantinople.[19]

Romanos I and Constantine VII, 920–959

Until this time, the Byzantine Empire had been concerned solely with survival and with holding on to what they already had. Numerous expeditions to Crete and Sicily were sadly reminiscent of the failures of Heraclius, even though the Arab conquest of Sicily did not go according to plan. After Leo's death in 912 the Empire became embroiled in problems with the regency of the seven-year-old Constantine VII and with invasions of Thrace by Simeon I of Bulgaria.[20]

The situation changed however when the admiral Romanos Lekapenos assumed power as a co-emperor with three of his rather useless sons and Constantine VII, thus ending the internal problems with the government. Meanwhile, the Bulgar problem more or less solved itself with the death of Simeon in 927, so Byzantine general John Kourkouas was able to campaign aggressively against the Saracens from 923 to about 950.[21] Armenia was consolidated within the Empire whilst Melitene, which had been a ruined emirate since the 9th century, was annexed at last. In 941 John Kourkouas was forced to turn his army north to fight off the invasion of Igor I of Kiev, but he was able to return to lay siege to Edessa—no Byzantine army had reached as far since the days of Heraclius. In the end the city was able to maintain its freedom when Al-Muttaqi agreed to give up a precious Christian relic: the "Image of Edessa".[22]

Constantine VII assumed full power in 945. Whilst his predecessor, Romanos I had managed to use diplomacy to keep peace in the West against the Bulgars, the East required the force of arms to achieve peace. Constantine VII turned to his most powerful ally, the Phocas family. Bardas Phokas the Elder had originally supported the claims of Constantine VII against those of Romanos I, and his position as strategos of the Armeniakon Theme made him the ideal candidate for war against the Caliphate.[23] Nevertheless, Bardas was wounded in 953 without much success, though his son Nikephoros Phokas was able to inflict a serious defeat on the Caliphate: Adata fell in 957 whilst Nikephoros' young nephew, John Tzimiskes, captured Samosata in the Euphrates valley in 958.[23]

Romanos II, 959–963

Romanos II launched the largest expedition by Byzantium since the days of Heraclius. A mammoth force of 50,000 men, 1,000 heavy transports, over 300 supply ships, and some 2,000 Greek Fire Ships under the brilliant Nikephoros Phokas set sail for Candia, the Islamic capital of Crete.[24] After an eight-month siege and a bitter winter,[24] Nikephoros sacked the city. News of the reconquest was met with great delight in Constantinople with a night-long service of thanksgiving was given by the Byzantines in the Hagia Sophia.[25]

Nikephoros saw none of this gratitude, denied a triumph due to Romanus II's fear of feeding his ambitions.[25] Instead, Nikephoros had to march rapidly to the East where Saif al-Daula of the Hamdanid dynasty, the Emir of Aleppo, had taken 30,000 men into Imperial territory,[25] attempting to take advantage of the army's absence in Crete. The Emir was one of the most powerful independent rulers in the Islamic world—his domains included Damascus, Aleppo, Emesa, and Antioch.[25] After a triumphant campaign, Saif was bogged down with overwhelming numbers of prisoners and loot. Leo Phokas, brother of Nikephoros, was unable to engage the Emir in an open battle with his small army. Instead, Saif found himself fleeing from battle with 300 cavalry and his army torn to pieces by a brilliantly planned ambush in the mountain passes of Asia Minor. With great satisfaction, Christian captives were substituted with recently acquired Muslims.[26]

When Nikephoros arrived and linked up with his brother, their army operated efficiently and had by early 962 returned some 55 walled tows in Cilicia to Byzantium.[26] Not many months later, the Phokas brothers were beneath the walls of Aleppo. The Byzantines stormed the city on December 23 destroying all but the citadel that was zealously held by a few soldiers of the Emir. Nikephoros ordered a withdrawal; the Emir of Aleppo was badly beaten and would no longer pose a threat.[26] The troops still holding out at the citadel were ignored with contempt. News of the death of Romanos II reached Nikephoros before he had left Cappadocia.

Byzantine resurgence, 963–1025

Nikephoros II Phocas, 963–969

Romanos II left behind Theophano, a beautiful empress widow, and four children, the eldest son being less than seven years. Like many regencies, that of Basil II proved chaotic and not without scheming of ambitious generals, such as Nikephoros, or internal fighting between Macedonian levies, Anatolians, and even the pious crowd of the Hagia Sophia.[27] When Nikephoros emerged triumphant in 963, he once more began campaigning against his Saracen opponents in the East.

In 965 Tarsus fell after a series of repeated Byzantine campaigns in Cilicia, followed by Cyprus that same year.[4] In 967 the defeated Saif of Mosul died of a stroke,[4] depriving Nikephoros of his only serious challenge there. Said had not fully recovered from the sack of Aleppo, which became an imperial vassal shortly thereafter. In 969, the city of Antioch was retaken by the Byzantines,[4] the first major city in Syria to be lost by the Arabs. Byzantine success was not total; in 964 another failed attempt was made to take Sicily by sending an army led by an illegitimate nephew of Nikephoros, Manuel Phokas. In 969, Nikephoros was murdered in his palace by John Tzimiskes, who took the throne for himself.[28]

John I Tzimiskes, 969–976

In 971 the new Fatimid Caliphate entered the scene. With newly found zeal, the Fatimids took Egypt, Palestine, and much of Syria from the powerless Abbasids, who were beginning to have their own Turkic problems.[5] Having defeated their Islamic opponents, the Fatimids saw no reason to stop at Antioch and Aleppo, cities in the hands of the Christian Byzantines, making their conquest more important. A failed attack on Antioch in 971 was followed up by a Byzantine defeat outside of Amida.[5] However, John I Tzimiskes would prove to be a greater foe than Nikephoros. With 10,000 Armenian troops and other levies he pushed south, relieving the Imperial possessions there and threatening Baghdad with an invasion. His reluctance to invade the Abbasid Capital, though poorly defended and demoralized, remains a mystery.[5]

After dealing with more Church matters, Tzimiskes returned in the spring of 975; Syria, Lebanon, and much of Palestine fell to the imperial armies of Byzantium.[29] It appears that Tzimiskes grew ill that year and the year after, halting his progress and sparing Jerusalem from a Christian victory.

Basil II Porphyrogennitus, 976–1025

The early reign of Basil II was distracted with civil wars across the Empire. After dealing with the invasions of Samuel of Bulgaria and the revolts of Bardas Phokas and Bardas Skleros, Basil turned his attention in 995 to Syria, where the Emir of Aleppo was in danger.[30] As an imperial vassal the Emir pleaded to the Byzantines for military assistance, since the city was under siege by Abu Mansoor Nizar al-Aziz Billah. Basil II rushed back to Constantinople with 40,000 men. He gave his army 80,000 mules, one for each soldier and another for their equipment.[30] The first 17,000 men arrived at Aleppo with great speed, and the hopelessly outnumbered Fatimid army withdrew. Basil II pursued it south, sacking Emesa and reaching as far as Tripoli.[30] Basil returned to the Bulgar front with no further campaigning against the Egyptian foe.

Warfare between the two powers continued as the Byzantines supported an anti-Fatimid uprising in Tyre. In 998, the Byzantines under the successor of Bourtzes, Damian Dalassenos, launched an attack on Apamea, but the Fatimid general Jaush ibn al-Samsama defeated them in battle on 19 July 998. This new defeat brought Basil II once again to Syria in October 999. Basil spent three months in Syria, during which the Byzantines raided as far as Baalbek, took and garrisoned Shaizar, and captured three minor forts in its vicinity (Abu Qubais, Masyath, and 'Arqah), and sacked Rafaniya. Hims was not seriously threatened, but a month-long siege of Tripolis in December failed. However, as Basil's attention was diverted to developments in Armenia, he departed for Cilicia in January and dispatched another embassy to Cairo. In 1000 a ten-year truce was concluded between the two states.[31][32] For the remainder of the reign of al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (r. 996–1021), relations remained peaceful, as Hakim was more interested in internal affairs. Even the acknowledgement of Fatimid suzerainty by Lu'lu' of Aleppo in 1004 and the Fatimid-sponsored installment of Fatik Aziz al-Dawla as the city's emir in 1017 did not lead to a resumption of hostilities, especially since Lu'lu' continued to pay tribute to Byzantium, and Fatik quickly began acting as an independent ruler.[33][34] Nevertheless, Hakim's persecution of Christians in his realm, and especially the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at his orders in 1009, strained relations and would, along with Fatimid interference in Aleppo, provide the main focus of Fatimid-Byzantine diplomatic relations until the late 1030s.[35]

Final battles

The military force of the Arab world had been in decline since the 9th century, illustrated by losses in Mesopotamia and Syria, and by the slow conquest of Sicily. While the Byzantines attained successes against the Arabs, a slow internal decay after 1025 a.d. was not arrested, precipitating a general decline of the Empire during the 11th century.[36] (This instability and decline ultimately featured a sharp decline in central Imperial authority, succession crises and weak legitimacy; a willful disintegration of the Theme system by the Constantinopolitan bureaucrats in favour of foreign mercenaries to suppress the growing power of the Anatolian military aristocracy; a decline of the free land-owning peasantry under pressure from the military aristocracy who created large Latifundia which displaced the peasantry, thus further undermining military manpower. Very frequent revolt and civil war between the bureaucrats and the military aristocracy for supremacy; which as a result facilitated unruly mercenaries and foreign raiders like the Turks or Pechenegs to plunder the interior with little meaningful resistance). The short and uneventful reign of Constantine VIII (1025–28) was followed by the incompetent Romanos III (1028–34). When Romanos marched his army to Aleppo, he was ambushed by the Arabs.[37] Despite this failure, Romanos' general George Maniaces was able to recover the region and defend Edessa against Arab attack in 1032. Romanos III's successor (and possibly his murderer) Michael IV the Paphlagonian ordered an expedition against Sicily under George Maniaces. Initial Byzantine success led to the fall of Messina in 1038, followed by Syracuse in 1040, but the expedition was riddled with internal strife and was diverted to a disastrous course against the Normans in southern Italy.[6]

Following the loss of Sicily and most of southern Italy, the Byzantine Empire collapsed into a state of petty inter-governmental strife. Isaac I Komnenos took power in 1057 with great ability and promise,[38] but his premature death, a brief two-years in power, was too short for effective lasting reform. The Fatimid and Abbasid Caliphate were already busy fighting the Seljuq dynasty. The Byzantines eventually mustered a great force to counter these threats under Romanos IV, co-emperor from 1068 to 1071. He marched to meet the Seljuk Turks, passing through an Anatolia verging on anarchy. His army was frequently ambushed by local Armenian subjects in revolt. Facing hardship to enter the Armenian Highlands, he ignored the truce made with the Seljuks and marched to retake recently lost fortresses around Manzikert. With part of his army ambushed and another part deserting, Romanos was defeated and captured at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 by Alp Arslan, head of the Great Seljuq Empire.[39][40] Although the defeat was minor, it triggered a devastating series of civil wars which saw Turkish raiders march largely unopposed to plunder deeper and deeper into Anatolia as well as rival Byzantine factions hire Turkish war bands to aid them in exchange for garrisoning cities. This saw most of the Asia Minor come under the rule of the Turkic raiders by 1091.[3]

In 1081 Alexius I Comnenus seized power and re-initiated the Komnenian dynasty, initiating a period of restoration. Byzantine attention was focused primarily on the Normans and the Crusades during this period, and they would not fight the Arabs again until the end of the reign of John II Comnenus.

Komnenian expeditions against Egypt

John II Komnenos pursued a pro-Crusader policy, actively defending the Crusader states against the forces of Zengi. His army marched and laid siege to Shaizar, but the Principality of Antioch betrayed the Byzantines with inactiveness.[41] John II therefore had little choice but to accept the Emir of Mosul's promise of vassalage and annual tribute to Byzantium.[41] The other choice would have been risking a battle whilst leaving his siege equipment in the hands of the untrustworthy Crusaders. John could have beaten Zengi, but Zengi was not the only potential foe for Byzantium.

John II died in 1143. The foolishness of the Principality of Antioch meant that Edessa fell, and now the great Patriarchate was on the front line.[42] A failed siege on Damascus in the Second Crusade forced the Kingdom to turn south against Egypt.[43] The new Byzantine Emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, enjoyed the idea of conquering Egypt, whose vast resources in grain and in native Christian manpower (from the Copts) would be no small reward, even if shared with the Crusaders. Alas, Manuel Komnenos worked too quickly for the Crusaders. After three months the Siege of Damietta in 1169 failed,[44] although the Crusaders received a mixed diet of defeat (with several invasions failing) and some victories. The Crusaders were able to negotiate with the Fatimids to surrender the capital to a small Crusader garrison and pay annual tribute,[45] but a Crusader breach of the treaty coupled with the rising power of the Muslims led to Saladin becoming master of Syria and Egypt.

In 1171, Amalric I of Jerusalem came to Constantinople in person, after Egypt had fallen to Saladin.[46] In 1177, a fleet of 150 ships was sent by Manuel I to invade Egypt, but it returned home after appearing off Acre due to the refusal of Philip, Count of Flanders, and many important nobles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to help.[47]

In that year Manuel Komnenos suffered a defeat in the Battle of Myriokephalon against Kilij Arslan II of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm.[48] Even so, the Byzantine Emperor continued to have an interest in Syria, planning to march his army south in a pilgrimage and show of strength against Saladin's might. Nonetheless, like many of Manuel's goals, this proved unrealistic, and he had to spend his final years working hard to restore the Eastern front against Iconium, which had deteriorated in the time wasted in fruitless Arab campaigns.

Notes

- Occasional alliances against Saracen piracy were concluded

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. p. 99.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 180.

- Norwich 1997, p. 192

- Norwich 1997, p. 202

- Norwich 1997, p. 221

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 189.

- Treadgold, Warren (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 131.

- Treadgold, Warren (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 144.

- Treadgold, Warren (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 139.

- Magdalino, Paul (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP. p. 171.

- Norwich 1997, p. 134

- Norwich 1997, p. 137

- Norwich 1997, p. 140

- Norwich 1997, p. 141

- Norwich 1997, p. 149

- Norwich 1997, p. 155

- Norwich 1997, p. 161

- Norwich 1997, p. 164

- Norwich 1997, pp. 168–174

- Norwich 1997, p. 174

- Norwich 1997, p. 177

- Norwich 1997, p. 181

- Norwich 1997, p. 184

- Norwich 1997, p. 185

- Norwich 1997, p. 186

- Norwich 1997, pp. 187–190

- Norwich 1997, p. 197

- Norwich 1997, p. 203

- Norwich 1997, p. 212

- Lev (1995), pp. 203–205

- Stevenson (1926), p. 252

- Lev (1995), p. 205

- Stevenson (1926), pp. 254–255

- Lev (1995), pp. 203, 205–208

- Norwich 1997, p. 217. The title page reads, "The Decline Begins, 1025 – 1055"

- Norwich 1997, p. 218

- Norwich 1997, p. 234

- Norwich 1997, p. 240

- Haldon 2002, pp. 45–46

- Norwich 1997, p. 271

- Norwich 1997, p. 272: "Not only had they made no further progress against the Saracens; they had failed even to preserve John's earlier conquests."

- Norwich 1997, p. 279

- Madden 2004, p. 69

- Madden 2004, p. 68

- Magdalino 1993, p. 75

* H.E. Mayer, The Latin East, 657 - J. Harris, Byzantium and The Crusades, 109

- Madden 2004, p. 71

References and further reading

- Haldon, John (2002). Byzantium at War 600 – 1453. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-360-6.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Madden, Thomas (2004). Crusades The Illustrated History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11463-4.

- Magdalino, Paul (1993). The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143-1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 55756894..

- Mango, Cyril (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814098-6.

- Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-679-77269-3.

- Santagati, Luigi (2012). Storia dei Bizantini di Sicilia. Caltanissetta: Lussografica. ISBN 978-88-8243-201-0.

- Sherrard, Philip (1966). Byzantium. New York: Time-Life Books. OCLC 506380.

- Treadgold, Warren (2001). A Concise History of Byzantium. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 0-333-71829-1.