Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (/ˈsiːzər/, SEE-zər; Latin: [ˈɡaːiʊs ˈjuːliʊs ˈkae̯sar]; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Julius Caesar | |

|---|---|

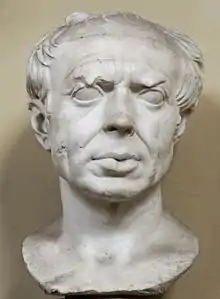

_(cropped).jpg.webp) The Tusculum portrait, possibly the only surviving sculpture of Caesar made during his lifetime, now housed at the Archaeological Museum in Turin, Italy | |

| Born | 12 July 100 BC[1] |

| Died | 15 March 44 BC (aged 55) Theatre of Pompey, Ancient Rome |

| Cause of death | Assassination (stab wounds) |

| Resting place | Temple of Caesar in Rome 41.891943°N 12.486246°E |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | |

| Office |

|

| Spouses | |

| Partner | Cleopatra |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Awards | Civic Crown |

| Military service | |

| Years of service | 81–45 BC |

| Battles/wars | |

In 60 BC, Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey formed the First Triumvirate, an informal political alliance that dominated Roman politics for several years. Their attempts to amass political power were opposed by many in the Senate, among them Cato the Younger with the private support of Cicero. Caesar rose to become one of the most powerful politicians in the Roman Republic through a string of military victories in the Gallic Wars, completed by 51 BC, which greatly extended Roman territory. During this time he both invaded Britain and built a bridge across the river Rhine. These achievements and the support of his veteran army threatened to eclipse the standing of Pompey, who had realigned himself with the Senate after the death of Crassus in 53 BC. With the Gallic Wars concluded, the Senate ordered Caesar to step down from his military command and return to Rome. In 49 BC, Caesar openly defied the Senate's authority by crossing the Rubicon and marching towards Rome at the head of an army.[3] This began Caesar's civil war, which he won, leaving him in a position of near-unchallenged power and influence in 45 BC.

After assuming control of government, Caesar began a programme of social and governmental reform, including the creation of the Julian calendar. He gave citizenship to many residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He initiated land reforms to support his veterans and initiated an enormous building programme. In early 44 he was proclaimed "dictator for life" (dictator perpetuo). Fearful of his power and domination of the state, Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators led by Brutus and Cassius on the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC. A new series of civil wars broke out and the constitutional government of the Republic was never fully restored. Caesar's great-nephew and adopted heir Octavian, later known as Augustus, rose to sole power after defeating his opponents in the last civil war of the Roman Republic. Octavian set about solidifying his power, and the era of the Roman Empire began.

Caesar was an accomplished author and historian as well as a statesman; much of his life is known from his own accounts of his military campaigns. Other contemporary sources include the letters and speeches of Cicero and the historical writings of Sallust. Later biographies of Caesar by Suetonius and Plutarch are also important sources. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history.[4] His cognomen was subsequently adopted as a synonym for "Emperor"; the title "Caesar" was used throughout the Roman Empire, giving rise to modern descendants such as Kaiser and Tsar. He has frequently appeared in literary and artistic works.

Early life and career

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a patrician family, the gens Julia on 12 July 100 BC.[5] The family claimed to have immigrated to Rome from Alba Longa during the seventh century BC after the third king of Rome, Tullus Hostilius, took and destroyed their city. The family also claimed descent from Julus, the son of Aeneas and founder of Alba Longa. Given that Aeneas was a son of Venus, this made the clan divine. This genealogy had not yet taken its final form by the first century, but the clan's claimed descent from Venus was well established in public consciousness.[6] There is no evidence that Caesar himself was born by Caesarian section; such operations entailed the death of the mother, but Caesar's mother lived for decades after his birth and no ancient sources record any difficulty with the birth.[7]

Despite their ancient pedigree, the Julii Caesares were not especially politically influential during the middle republic. The first person known to have had the cognomen Caesar was a praetor in 208 BC during the Second Punic War. The family's first consul was in 157 BC, though their political fortunes had recovered in the early first century, producing two consuls in 91 and 90 BC.[8] Caesar's homonymous father was moderately successful politically. He married Aurelia, a member of the politically influential Aurelii Cottae, producing – along with Caesar – two daughters. Buoyed by his own marriage and his sister's marriage (the dictator's aunt) with the extremely influential Gaius Marius, he also served on the Saturninian land commission in 103 BC and was elected praetor some time between 92 and 85 BC; he served as proconsular governor of Asia for two years, likely 91–90 BC.[9]

Life under Sulla and military service

.jpg.webp)

Caesar's father did not seek a consulship during the domination of Lucius Cornelius Cinna and instead chose retirement.[10] During Cinna's dominance, Caesar was named as flamen Dialis (a priest of Jupiter) which led to his marriage to Cinna's daughter, Cornelia. The religious taboos of the priesthood would have forced Caesar to forego a political career; the appointment – one of the highest non-political honours – indicates that there were few expectations of a major career for Caesar.[11] In early 84 BC, Caesar's father died suddenly.[12] After Sulla's victory in the civil war (82 BC), Cinna's acta were annulled. Sulla consequently ordered Caesar to abdicate and divorce Cinna's daughter. Caesar refused, implicitly questioning the legitimacy of Sulla's annulment. Sulla may have put Caesar on the proscription lists, though scholars are mixed.[13] Caesar then went into hiding before his relatives and contacts among the Vestal Virgins were able to intercede on his behalf.[14] They then reached a compromise where Caesar would resign his priesthood but keep his wife and chattels; Sulla's alleged remark he saw "in [Caesar] many Mariuses"[15] is apocryphal.[16]

Caesar then left Italy to serve in the staff of the governor of Asia, Marcus Minucius Thermus. While there, he travelled to Bithynia to collect naval reinforcements and stayed some time as a guest of the king, Nicomedes IV, though later invective connected Caesar to a homosexual relation with the monarch.[17][18] He then served at the Siege of Mytilene where he won the civic crown for saving the life of a fellow citizen in battle. The privileges of the crown – the Senate was supposed to stand on a holder's entrance and holders were permitted to wear the crown at public occasions – whetted Caesar's appetite for honours. After the capture of Mytilene, Caesar transferred to the staff of Publius Servilius Vatia in Cilicia before learning of Sulla's death in 78 BC and returning home immediately.[19] He was alleged to have wanted to join in on the consul Lepidus' revolt that year[20] but this is likely literary embellishment of Caesar's desire for tyranny from a young age.[21]

Afterward, Caesar attacked some of the Sullan aristocracy in the courts but was unsuccessful in his attempted prosecution of Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella in 77 BC, who had recently returned from a proconsulship in Macedonia. Going after a less well-connected senator, he was successful the next year in prosecuting Gaius Antonius Hybrida (later consul in 63 BC) for profiteering from the proscriptions but was forestalled when a tribune interceded on Antonius' behalf.[22] After these oratorical attempts, Caesar left Rome for Rhodes seeking the tutelage of the rhetorician Apollonius Molon.[23] While travelling, he was intercepted and ransomed by pirates in a story that was later much embellished. According to Plutarch and Suetonius, he was freed after paying a ransom of fifty talents and responded by returning with a fleet to capture and execute the pirates. The recorded sum for the ransom is literary embellishment and it is more likely that the pirates were sold into slavery per Velleius Paterculus.[24] His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the Third Mithridatic War over the winter of 75 and 74 BC; Caesar is alleged to have gone around collecting troops in the province at the locals' expense and leading them successfully against Mithridates' forces.[25]

Entrance to politics

While absent from Rome, in 73 BC, Caesar was co-opted into the pontifices in place of his deceased relative Gaius Aurelius Cotta. The promotion marked him as a well-accepted member of the aristocracy with great future prospects in his political career.[26] Caesar decided to return shortly thereafter and on his return was elected one of the military tribunes for 71 BC.[27] There is no evidence that Caesar served in war – even though the war on Spartacus was on-going – during his term; he did, however, agitate for the removal of Sulla's disabilities on the plebeian tribunate and for those who supported Lepidus' revolt to be pardoned.[28] These advocacies were common and uncontroversial.[29] The next year, 70 BC, Pompey and Crassus were consuls and brought legislation restoring the plebeian tribunate's rights; one of the tribunes, with Caesar supporting, then brought legislation pardoning the Lepidan exiles.[30]

For his quaestorship in 69 BC, Caesar was allotted to serve under Gaius Antistius Vetus in Hispania Ulterior. His election also gave him a lifetime seat in the Senate. However, before he left, his aunt Julia, the widow of Marius died and, soon afterwards, his wife Cornelia died shortly after bearing his only legitimate child, Julia. He gave eulogies for both at public funerals.[31] During Julia's funeral, Caesar displayed the images of his aunt's husband Marius, whose memory had been suppressed after Sulla's victory in the civil war. Some of the Sullan nobles – including Quintus Lutatius Catulus – who had suffered under the Marian regime objected, but by this point depictions of husbands in aristocratic women's funerary processions was common.[32] Contra Plutarch,[33] Caesar's action here was likely in keeping with a political trend for reconciliation and normalisation rather than a display of renewed factionalism.[34] Caesar quickly remarried, taking the hand of Sulla's granddaughter Pompeia.[35]

Aedileship and election as pontifex maximus

For much of this period, Caesar was one of Pompey's supporters. Caesar joined with Pompey in the late 70s to support restoration of tribunician rights; his support for the law recalling the Lepidan exiles may have been related to the same tribune's bill to grant lands to Pompey's veterans. Caesar also supported the lex Gabinia in 67 BC granting Pompey an extraordinary command against piracy in the Mediterranean and also supported the lex Manilia in 66 BC to reassign the Third Mithridatic War from its then-commander Lucullus to Pompey.[36]

Four years after his aunt Julia's funeral, in 65 BC, Caesar served as curule aedile and staged lavish games that won him further attention and popular support.[37] He also restored the trophies won by Marius, and taken down by Sulla, over Jugurtha and the Cimbri.[38] According to Plutarch's narrative, the trophies were restored overnight to the applause and tears of joy of the onlookers; any sudden and secret restoration of this sort would not have been possible – architects, restorers, and other workmen would have to have been hired and paid for – nor would it have been likely that the work could have been done in a single night.[39] It is more likely that Caesar was merely restoring his family's public monuments – consistent with standard aristocratic practice and the virtue of pietas – and, over objections from Catulus, these actions were broadly supported by the Senate.[40]

In 63 BC, Caesar stood for the praetorship and also for the post of pontifex maximus,[41] who was the head of the College of Pontiffs and the highest ranking state religious official. In the pontifical election before the tribes, Caesar faced two influential senators: Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Publius Servilius Isauricus. Caesar came out victorious. Many scholars have expressed astonishment that Caesar's candidacy was taken seriously, but this was not without historical precedent.[42] Ancient sources allege that Caesar paid huge bribes or was shamelessly ingratiating;[43] that no charge was ever laid alleging this implies that bribery alone is insufficient to explain his victory.[44] If bribes or other monies were needed, they may have been underwritten by Pompey, whom Caesar at this time supported and who opposed Catulus' candidacy.[45]

Many sources also assert that Caesar supported the land reform proposals brought that year by plebeian tribune Publius Servilius Rullus, however, there are no ancient sources so attesting.[46] Caesar also engaged in a collateral manner in the trial of Gaius Rabirius by one of the plebeian tribunes – Titus Labienus – for the murder of Saturninus in accordance with a senatus consultum ultimum some forty years earlier.[47][48] The most famous event of the year was the Catilinarian conspiracy. While some of Caesar's enemies, including Catulus, alleged that he participated in the conspiracy,[49] the chance that he was a participant is extremely small.[50]

Praetorship

Caesar won his election to the praetorship in 63 BC easily and, as one of the praetor-elects, spoke out that December in the Senate against executing certain citizens who had been arrested in the city conspiring with Gauls in furtherance of the conspiracy.[51] Caesar's proposal at the time is not entirely clear. The earlier sources assert that he advocated life imprisonment without trial; the later sources assert he instead wanted the conspirators imprisoned pending trial. Most accounts agree that Caesar supported confiscation of the conspirators' property.[52] Caesar likely advocated the former, which was a compromise position that would place the Senate within the bounds of the lex Sempronia de capite civis, and was initially successful in swaying the body; a later intervention by Cato, however, swayed the Senate at the end for execution.[53]

During his year as praetor, Caesar first attempted to deprive his enemy Catulus of the honour of completing the rebuilt Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, accusing him of embezzling funds, and threatening to bring legislation to reassign it to Pompey. This proposal was quickly dropped amid near-universal opposition.[54] He then supported the attempt by plebeian tribune Metellus Nepos to transfer the command against Catiline from the consul of 63, Gaius Antonius Hybrida, to Pompey. After a violent meeting of the comitia tributa in the forum, where Metellus came into fisticuffs with his tribunician colleagues Cato and Quintus Minucius Thermus,[55] the Senate passed a decree against Metellus – Suetonius claims that both Nepos and Caesar were deposed from their magistracies; this would have been a constitutional impossibility[56] – which led Caesar to distance himself from the proposals: hopes for a provincial command and need to repair relations with the aristocracy took priority.[57] He also was engaged in the Bona Dea affair, where Publius Clodius Pulcher snuck into Caesar's house sacrilegiously during a female religious observance; Caesar avoided any part of the affair by divorcing his wife immediately – claiming that his wife needed to be "above suspicion"[58] – but there is no indication that Caesar supported Clodius in any way.[59]

After his praetorship, Caesar was appointed to govern Hispania Ulterior pro consule.[61] Deeply indebted from his campaigns for the praetorship and for the pontificate, Caesar required military victory beyond the normal provincial extortion to pay them off.[62] He campaigned against the Callaeci and Lusitani and seized the Callaeci capital in northwestern Spain, bringing Roman troops to the Atlantic and seizing enough plunder to pay his debts.[63] Claiming to have completed the peninsula's conquest, he made for home after having been hailed imperator.[64] When he arrived home in the summer of 60 BC, he was then forced to choose between a triumph and election to the consulship: either he could remain outside the pomerium (Rome's sacred boundary) awaiting a triumph or cross the boundary, giving up his command and triumph, to make a declaration of consular candidacy.[65] Attempts to waive the requirement for the declaration to be made in person were filibustered in the Senate by Caesar's enemy Cato, even though the Senate seemed to support the exception.[66] Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship.[67]

First consulship and the Gallic wars

Caesar stood for the consulship of 59 BC along with two other candidates. His political position at the time was strong: he had supporters among the families which had supported Marius or Cinna; his connection with the Sullan aristocracy was good; his support of Pompey had won him support in turn. His support for reconciliation in continuing aftershocks of the civil war was popular in all parts of society.[68] With the support of Crassus, who supported Caesar's joint ticket with one Lucius Lucceius, Caesar won. Lucceius, however, did not and the voters returned Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus instead, one of Caesar's long-standing personal and political enemies.[69][70]

First consulship

After the elections, Caesar reconciled Pompey and Crassus, two political foes, in a three-way alliance misleadingly[71] termed the "First Triumvirate" in modern times. Caesar was still at work in December of 60 BC attempting to find allies for his consulship and the alliance was finalised only some time around its start.[72] Pompey and Crassus joined in pursuit of two respective goals: the ratification of Pompey's eastern settlement and the bailing out of tax farmers in Asia, many of whom were Crassus' clients. All three sought the extended patronage of land grants, with Pompey especially seeking the promised land grants for his veterans.[73]

Caesar's first act was to publish the minutes of the Senate and the assemblies, signalling the Senate's accountability to the public. He then brought in the Senate a bill – crafted to avoid objections to previous land reform proposals and any indications of radicalism – to purchase property from willing sellers to distribute to Pompey's veterans and the urban poor. It would be administered by a board of twenty (with Caesar excluded), and financed by Pompey's plunder and territorial gains.[74] Referring it to the Senate in hope that it would take up the matter to show its beneficence for the people,[75] there was little opposition and the obstructionism that occurred was largely unprincipled, firmly opposing it not on grounds of public interest but rather opposition to Caesar's political advancement.[74] Unable to overcome Cato's filibustering, he moved the bill before the people and, at a public meeting, Caesar's co-consul Bibulus threatened a permanent veto for the entire year. This clearly violated the people's well-established legislative sovereignty[76] and triggered a riot in which Bibulus' fasces were broken, symbolising popular rejection of his magistracy.[77] The bill was then voted through. Bibulus attempted to induce the Senate to nullify it on grounds it was passed by violence and contrary to the auspices but the Senate refused.[78]

Caesar also brought and passed a one-third write-down of tax farmers' arrears for Crassus and ratification of Pompey's eastern settlements. Both bills were passed with little or no debate in the Senate.[79] Caesar then moved to extend his agrarian bill to Campania some time in May; this may be when Bibulus withdrew to his house.[80] Pompey, shortly thereafter, also wed Caesar's daughter Julia to seal their alliance.[81] An ally of Caesar's, plebeian tribune Publius Vatinius moved the lex Vatinia assigning the provinces of Illyricum and Cisalpine Gaul to Caesar for five years.[82][83] Suetonius' claim that the Senate had assigned to Caesar the silvae callesque ("woods and tracks") is likely an exaggeration: fear of Gallic invasion had grown in 60 BC and it is more likely that the consuls had been assigned to Italy, a defensive posture that Caesarian partisans dismissed as "mere 'forest tracks'".[84] The Senate was also persuaded to assign to Caesar Transalpine Gaul as well, subject to annual renewal, most likely to control his ability to make war on the far side of the Alps.[85]

Some time in the year, perhaps after the passing of the bill distributing the Campanian land[86] and after these political defeats, Bibulus withdrew to his house. There, he issued edicts in absentia, purporting unprecedentedly to cancel all days on which Caesar or his allies could hold votes for religious reasons.[87] Cato too attempted symbolic gestures against Caesar, which allowed him and his allies to "feign victimisation"; these tactics were successful in building revulsion to Caesar and his allies through the year.[88][89] This opposition caused serious political difficulties to Caesar and his allies, belying the common depiction of triumviral political supremacy.[90] Later in the year, however, Caesar – with the support of his opponents – brought and passed the lex Julia de repetundis to crack down on provincial corruption.[91] When his consulship ended, Caesar's legislation was challenged by two of the new praetors but discussion in the Senate stalled and was regardless dropped. He stayed near the city until some time around mid-March.[92]

Caesar in Gaul

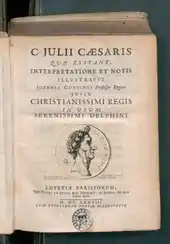

During the Gallic Wars, Caesar wrote his Commentaries thereon, which were acknowledged even in his time as a Latin literary masterwork. Meant to document Caesar's campaigns in his own words and maintain support in Rome for his military operations and career, he produced some ten volumes covering operations in Gaul from 58 to 52 BC.[93] Each was likely produced in the year following the events described and was likely aimed at the general, or at least literate, population in Rome;[94] the account is naturally partial to Caesar – his defeats are excused and victories highlighted – but it is almost the sole source for events in Gaul in this period.[95]

Gaul in 58 BC was in the midst of some instability. Tribes had raided into Transalpine Gaul and there was an on-going struggle between two tribes in central Gaul which collaterally involved Roman alliances and politics. The divisions within the Gauls – they were no unified bloc – would be exploited in the coming years.[96] The first engagement was in April 58 BC when Caesar prevented the migrating Helvetii from moving through Roman territory, allegedly because he feared they would unseat a Roman ally.[97] Building a wall, he stopped their movement near Geneva and – after raising two legions – defeated them at the Battle of Bibracte before forcing them to return to their original homes.[98] He was drawn further north responding to requests from Gallic tribes, including the Aedui, for aid against Ariovistus – king of the Suebi and a declared friend of Rome by the Senate during Caesar's own consulship – and he defeated them at the Battle of Vosges.[99] Wintering in northeastern Gaul near the Belgae in the winter of 58–57, Caesar's forward military position triggered an uprising to remove his troops; able to eke out a victory at the Battle of the Sabis, Caesar spent much of 56 BC suppressing the Belgae and dispersing his troops to campaign across much of Gaul, including against the Veneti in what is now Brittany.[100] At this point, almost all of Gaul – except its central regions – fell under Roman subjugation.[101]

Seeking to buttress his military reputation, he engaged Germans attempting to cross the Rhine, which marked it as a Roman frontier;[101] displaying Roman engineering prowess, he here built a bridge across the Rhine in a feat of engineering meant to show Rome's ability to project power.[102] Ostensibly seeking to interdict British aid to his Gallic enemies, he led expeditions into southern Britain in 55 and 54 BC, perhaps seeking further conquests or otherwise wanting to impress readers in Rome; Britain at the time was to the Romans an "island of mystery" and "a land of wonder".[103] He, however, withdrew from the island in the face of winter uprisings in Gaul led by the Eburones and Belgae starting in late 54 BC which ambushed and virtually annihilated a legion and five cohorts.[104] Caesar was, however, able to lure the rebels into unfavourable terrain and routed them in battle.[105] The next year, a greater challenge emerged with the uprising of most of central Gaul, led by Vercingetorix of the Averni. Caesar was initially defeated at Gergovia before besieging Vercingetorix at Alesia. After becoming himself besieged, Caesar won a major victory which forced Vercingetorix's surrender; Caesar then spent much of his time into 51 BC suppressing any remaining resistance.[106]

Politics, Gaul, and Rome

In the initial years from the end of Caesar's consulship in 59 BC, the three so-called triumvirs sought to maintain the goodwill of the extremely popular Publius Clodius Pulcher,[107] who was plebeian tribune in 58 BC and in that year successfully sent Cicero into exile. When Clodius took an anti-Pompeian stance later that year, he unsettled Pompey's eastern arrangements, started attacking the validity of Caesar's consular legislation, and by August 58 forced Pompey into seclusion. Caesar and Pompey responded by successfully backing the election of magistrates to recall Cicero from exile on the condition that Cicero would refrain from criticism or obstruction of the allies.[108][109][110]

Politics in Rome falling into violent street clashes between Clodius and two tribunes who were friends of Cicero. With Cicero now supporting the Caesar and Pompey, Caesar sent news of Gaul to Rome and claimed total victory and pacification. The Senate at Cicero's motion voted him an unprecedented fifteen days of thanksgiving.[111] Such reports were necessary for Caesar, especially in light of senatorial opponents, to prevent the Senate from reassigning his command in Transalpine Gaul, even if his position in Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum was guaranteed by the lex Vatinia until 54 BC.[112] His success was evidently recognised when the Senate voted state funds for some of Caesar's legions, which until this time Caesar had paid for personally.[113]

The three allies' relations broke down in 57 BC: one of Pompey's allies challenged Caesar's land reform bill and the allies had a poor showing in the elections that year.[114] With a real threat to Caesar's command and acta brewing in 56 BC under the aegis of the unfriendly consuls, Caesar needed his allies' political support.[115] Pompey and Crassus too wanted military commands. Their combined interests led to a renewal of the alliance; drawing in the support of Appius Claudius Pulcher and his younger brother Clodius for the consulship of 54 BC, they planned second consulships with following governorships in 55 BC for both Pompey and Crassus. Caesar, for his part, would receive a five-year extension of command.[116]

Cicero was induced to oppose reassignment of Caesar's provinces and to defend a number of the allies' clients; his gloomy predictions of a triumviral set of consuls-designate for years on end proved an exaggeration when, only by desperate tactics, bribery, intimidation and violence were Pompey and Crassus elected consuls for 55 BC.[117] During their consulship, Pompey and Crassus passed – with some tribunician support – the lex Pompeia Licinia extending Caesar's command and the lex Trebonia giving them respective commands in Spain and Syria,[118] though Pompey never left for the province and remained politically active at Rome.[119] The opposition again unified against their heavy-handed political tactics – though not against Caesar's activities in Gaul[120] – and defeated the allies in the elections of that year.[121]

The ambush and destruction in Gaul of a legion and five cohorts in the winter of 55–54 BC produced substantial concern in Rome about Caesar's command and competence, evidenced by the highly defensive narrative in Caesar's Commentaries.[122] The death of Caesar's daughter and Pompey's wife Julia in childbirth c. late August 54 did not create a rift between Caesar and Pompey.[123][124][125] At the start of 53 BC, Caesar sought and received reinforcements by recruitment and a private deal with Pompey before two years of largely unsuccessful campaigning against Gallic insurgents.[126] In the same year, Crassus's campaign ended in disaster at the Battle of Carrhae, culminating in his death at the hands of the Parthians. When in 52 BC Pompey started the year with a sole consulship to restore order to the city,[127] Caesar was in Gaul suppressing insurgencies; after news of his victory at Alesia, with the support of Pompey he received twenty days of thanksgiving and, pursuant to the "Law of the Ten Tribunes", the right to stand for the consulship in absentia.[128][129]

Civil war

.jpg.webp)

From the period 52 to 49 BC, trust between Caesar and Pompey disintegrated.[130] In 51 BC, the consul Marcellus proposed recalling Caesar, arguing that his provincia (here meaning "task") in Gaul – due to his victory against Vercingetorix in 52 – was complete; it evidently was incomplete as Caesar was that year fighting the Bellovaci[131] and regardless the proposal was vetoed.[132] That year, it seemed that the conservatives around Cato in the Senate would seek to enlist Pompey to force Caesar to return from Gaul without honours or a second consulship.[133] Cato, Bibulus, and their allies, however, were successful in winning Pompey over to take a hard line against Caesar's continued command.[134]

As 50 BC progressed, fears of civil war grew; both Caesar and his opponents started building up troops in southern Gaul and northern Italy, respectively.[135] In the autumn, Cicero and others sought disarmament by both Caesar and Pompey, and on 1 December 50 BC this was formally proposed in the Senate.[136] It received overwhelming support – 370 to 22 – but was not passed when one of the consuls dissolved the meeting.[137] That year, when a rumour came to Rome that Caesar was marching into Italy, both consuls instructed Pompey to defend Italy, a charge he accepted as a last resort.[138] At the start of 49 BC, Caesar's renewed offer that he and Pompey disarm was read to the Senate and was rejected by the hardliners.[139] A later compromise given privately to Pompey was also rejected at their insistence.[140] On 7 January, his supportive tribunes were driven from Rome; the Senate then declared Caesar an enemy and it issued its senatus consultum ultimum.[141]

There is scholarly disagreement as to the specific reasons why Caesar marched on Rome. A very popular theory is that Caesar was forced to choose – when denied the immunity of his proconsular tenure – between prosecution, conviction, and exile or civil war in defence of his position.[142][143] Whether Caesar actually would have been prosecuted and convicted is debated. Some scholars believe the possibility of successful prosecution was extremely unlikely.[144][145] Caesar's main objectives were to secure a second consulship – first mooted in 52 as colleague to Pompey's sole consulship[146] – and a triumph. He feared that his opponents – then holding both consulships for 50 BC – would reject his candidacy or refuse to ratify an election he won.[147] This also was the core of his war justification: that Pompey and his allies were planning, by force if necessary (indicated in the expulsion of the tribunes[148]), to suppress the liberty of the Roman people to elect Caesar and honour his accomplishments.[149]

Italy, Spain, and Greece

Around 10 or 11 January 49 BC,[150][151] in response to the Senate's "final decree",[152] Caesar crossed the Rubicon – the river defining the northern boundary of Italy – with a single legion, the Legio XIII Gemina, and ignited civil war. Upon crossing the Rubicon, Caesar, according to Plutarch and Suetonius, is supposed to have quoted the Athenian playwright Menander, in Greek, "let the die be cast".[153] Pompey and many senators fled south, believing that Caesar was marching quickly for Rome.[154] Caesar, after capturing communication routes to Rome, paused and opened negotiations, but they fell apart amid mutual distrust.[155] Caesar responded by advancing south, seeking to capture Pompey to force a conference.[156]

Pompey withdrew to Brundisium and was able to escape to Greece, abandoning Italy in face of Caesar's superior forces and evading Caesar's pursuit.[157] Caesar stayed near Rome for about two weeks – during his stay his forceful seizure of the treasury over tribunician veto put the lie to his pro-tribunician war justifications – and left Lepidus in charge of Italy while he attacked Pompey's Spanish provinces.[158][159] He defeated two of Pompey's legates at the Battle of Ilerda before forcing surrender of the third; his legates moved into Sicily and into Africa, though the African expedition failed.[160] Returning to Rome in the autumn, Caesar had Lepidus, as praetor, bring a law appointing Caesar dictator to conduct the elections; he, along with Publius Servilius Isauricus, won the following elections and would serve as consuls for 48 BC.[161] Resigning the dictatorship after eleven days,[162] Caesar then left Italy for Greece to stop Pompey's preparations, arriving in force in early 48 BC.[163]

Caesar besieged Pompey at Dyrrhachium, but Pompey was able to break out and force Caesar's forces to flee. Following Pompey southeast into Greece and to save one of his legates, he engaged and decisively defeated Pompey at Pharsalus on 9 August 48 BC. Pompey then fled for Egypt; Cato fled for Africa; others, like Cicero and Marcus Junius Brutus, begged for Caesar's pardon.[164]

Alexandrine war and Asia Minor

Pompey was killed when he arrived in Alexandria, the capital of Egypt. Caesar arrived three days later on 2 October 48 BC. Prevented from leaving the city by Etesian winds, Caesar decided to arbitrate an Egyptian civil war between the child pharaoh Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator and Cleopatra, his sister, wife, and co-regent queen.[167] In late October 48 BC, Caesar was appointed in absentia to a year-long dictatorship,[168] after news of his victory at Pharsalus arrived to Rome.[169] While in Alexandria, he started an affair with Cleopatra and withstood a siege by Ptolemy and his other sister Arsinoe until March 47 BC. Reinforced by eastern client allies under Mithridates of Pergamum, he then defeated Ptolemy at the Battle of the Nile and installed Cleopatra as ruler.[170] Caesar and Cleopatra celebrated the victory with a triumphal procession on the Nile. He stayed in Egypt with Cleopatra until June or July that year, though the relevant commentaries attributed to him give no such impression. Some time in late June, Cleopatra gave birth to a child by Caesar, called Caesarion.[171]

When Caesar landed at Antioch, he learnt that during his time in Egypt, the king of what is now Crimea, Pharnaces, had attempted to seize what had been his father's kingdom, Pontus, across the Black Sea in northern Anatolia. His invasion had swept aside Caesar's legates and the local client kings, but Caesar engaged him at Zela and defeated him immediately, leading Caesar to write veni, vidi, vici ("I came, I saw, I conquered"), downplaying Pompey's previous Pontic victories. He then left quickly for Italy.[172]

Italy, Africa, and Spain

Caesar's absence from Italy put Mark Antony, as magister equitum, in charge. His rule was unpopular: Publius Cornelius Dolabella, serving as plebeian tribune in 47 BC, agitated for debt relief and after that agitation got out of hand the Senate moved for Antony to restore order. Delayed by a mutiny in southern Italy, he returned and suppressed the riots by force, killing many and delivering a similar blow to his popularity. Cato had marched to Africa[173] and there Metellus Scipio was in charge of the remaining republicans; they allied with Juba of Numidia; what used to be Pompey's fleet also raided the central Mediterranean islands. Caesar's governor in Spain, moreover, was sufficiently unpopular that the province revolted and switched to the republican side.[174]

Caesar demoted Antony on his return and pacified the mutineers without violence[175] before overseeing the election of the rest of the magistrates for 47 BC – no elections had yet been held – and also for those of 46 BC. Caesar would serve with Lepidus as consul in 46; he borrowed money for the war, confiscated and sold the property of his enemies at fair prices, and then left for Africa on 25 December 47 BC.[176] Caesar's landing in Africa was marked with some difficulties establishing a beachhead and logistically. He was defeated by Titus Labienus at Ruspina on 4 January 46 BC and thereafter took a rather cautious approach.[177] After inducing some desertions from the republicans, Caesar ended up surrounded at Thapsus. His troops attacked prematurely on 6 April 46 BC, starting a battle; they then won it and massacred the republican forces without quarter. Marching on Utica, where Cato commanded, Caesar arrived to find that Cato had killed himself rather than receive Caesar's clemency.[178] Many of the remaining anti-Caesarian leaders, including Metellus Scipio and Juba, also committed suicide shortly thereafter.[179] Labienus and two of Pompey's sons, however, had moved to the Spanish provinces in revolt. Caesar started a process of annexing parts of Numidia and then returned to Italy via Sardinia in June 46 BC.[180]

Caesar stayed in Italy to celebrate four triumphs in late September, supposedly over four foreign enemies: Gaul, Egypt, Pharnaces (Asia), and Juba (Africa). He led Vercingetorix, Cleopatra's younger sister Arsinoe, and Juba's son before his chariot; Vercingetorix was executed.[180] According to Appian, in some of the triumphs, Caesar paraded pictures and models of his victories over fellow Romans in the civil wars, to popular dismay.[181] The soldiers were each given 24,000 sesterces (a lifetime's worth of pay); further games and celebrations were put on for the plebs. Near the end of the year, Caesar heard bad news from Spain and, with an army, left for the peninsula, leaving Lepidus in charge as magister equitum.[182]

At a bloody battle at Munda on 17 March 45 BC, Caesar narrowly found victory;[183] his enemies were treated as rebels and he had them massacred.[184] Labienus died on the field. While one of Pompey's sons, Sextus, escaped, the war was effectively over.[185] Caesar remained in the province until June before setting out for Rome, arriving in October of the same year, and celebrated an unseemly triumph over fellow Romans.[184] By this point he had started preparations for war on the Parthians to avenge Crassus' death at Carrhae in 53 BC, with wide-ranging objectives that would take him into Dacia for three or more years. It was set to start on 18 March 44 BC.[186]

Assassination

Dictatorships and honours

Prior to Caesar's assumption of the title dictator perpetuo in February 44 BC, he had been appointed dictator some four times since his first dictatorship in 49 BC. After occupying Rome, he engineered this first appointment, largely to hold elections; after 11 days he resigned. The other dictatorships lasted for longer periods, up to a year, and by April 46 BC he was given a new dictatorship annually.[187] The task he was assigned revived that of Sulla's dictatorship: rei publicae constituendae.[188] These appointments, however, were not the source of legal power themselves; in the eyes of the literary sources, they were instead honours and titles which reflected Caesar's dominant position in the state, secured not by extraordinary magistracy or legal powers, but by personal status as victor over other Romans.[189]

Through the period after Pharsalus, the Senate showered Caesar with honours,[190] including the title praefectus moribus (lit. 'prefect of morals') which historically was associated with the censorial power to revise the Senate rolls. He was also granted power over war and peace,[191] usurping a power traditionally held by the comitia centuriata.[192] These powers attached to Caesar personally.[193] Similarly extraordinary were a number of symbolic honours which saw Caesar's image put onto Roman coinage – the first for a living Roman – with special rights to wear royal dress, sit atop a golden chair in the Senate, and have his statues erected in public temples. The month Quintilis, in which he was born, was renamed Julius (now July).[194] These were symbols of divine monarchy and, later, objects of resentment.

The decisions on the normal operation of the state – justice, legislation, administration, and public works – were concentrated into Caesar's person without regard for or even notice given to the traditional institutions of the republic.[195] Caesar's domination over public affairs and his competitive instinct to preclude all others alienated the political class and led eventually to the conspiracy against his life.[196]

Legislation

Caesar, as far as is attested in evidence, did not intend to restructure Roman society. Ernst Badian, writing in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, noted that although Caesar did implement a series of reforms, they did not touch on the core of the republican system: he "had no plans for basic social and constitutional reform" and that "the extraordinary honours heaped upon him... merely grafted him as an ill-fitting head on to the body of the traditional structure".[188]

The most important of Caesar's reforms was to the calendar, which saw the abolition of the traditional republican lunisolar calendar and its replacement with a solar calendar now called the Julian calendar.[197] He also increased the number of magistrates and senators (from 600 to 900) to better administer the empire and reward his supporters with offices. Colonies also were founded outside Italy – notably on the sites of Carthage and Corinth, which had both been destroyed during Rome's 2nd century BC conquests – to discharge Italy's population into the provinces and reduce unrest.[198] The royal power of naming patricians was revived to benefit the families of his men[199] and the permanent courts jury pools were also altered to remove the tribuni aerarii, leaving only the equestrians and senators.[200]

He also took further administrative actions to stabilise his rule and that of the state.[201] Caesar reduced the size of the grain dole from 320,000 down to around 150,000 by tightening the qualifications; special bonuses were offered to families with many children to stall depopulation.[202] Plans were drawn for the conduct of a census. Citizenship was extended to a number of communities in Cisalpine Gaul and to Cádiz.[203] During the civil wars, Caesar had also instituted a novel debt repayment programme (no debts would be forgiven but they could be paid in kind), remitted rents up to a certain amount, and thrown games distributing food.[204] Many of his enemies during the civil wars were pardoned – Caesar's clemency was exalted in his propaganda and temple works – with the intent to cultivate gratitude and draw a contrast between himself and the vengeful dictatorship of Sulla.[205]

The building programmes, started prior to his expedition to Spain, continued, with the construction of the Forum of Caesar and the Temple of Venus Genetrix therein. Other public works, including an expansion of Ostia's port and a canal through the Corinthian Isthmus, were also planned. Very busy with this work, the heavy-handedness with which he ignored the Senate, magistrates, and those who came to visit him also alienated many in Rome.[206]

The collegia, civic associations restored by Clodius in 58 BC, were again abolished.[202] His actions to reward his supporters saw him allow his subordinates illegal triumphal processions and resign the consulship on the last day of the year so any ally could be elected as suffect consul for a single day.[207] Corruption on the part of his partisans was also overlooked to ensure their support; provincial cities and client kingdoms were extorted for favours to pay his bills.[208]

Conspiracy and death

Attempts in January 44 BC to call Caesar rex (lit. 'king') – a title associated with arbitrary oppression against citizens – were shut down by two tribunes before a supportive crowd. Caesar, claiming that the two tribunes infringed on his honour by doing so, had them deposed from office and ejected from the Senate.[210] The incident both undermined Caesar's original arguments for pursuing the civil war (protecting the tribunes) and angered a public which still revered the tribunes as protectors of popular freedom.[211] Shortly before 15 February 44 BC, he assumed the dictatorship for life, putting an end to any hopes that his powers would be merely temporary.[212] Just days after his assumption of the life dictatorship, he publicly rejected a diadem from Antony at celebrations for the Lupercalia. Interpretations of the episode vary: he may have been rejecting the diadem publicly only because the crowd was insufficiently supportive; he could have done it performatively to signal he was no monarch; alternatively, Antony could have acted on his own initiative. By this point, however, rumour was rife that Caesar – already wearing the dress of a monarch – sought a formal crown and the episode did little to reassure.[213]

The plan to assassinate Caesar had started by the summer of 45 BC. An attempt to recruit Antony was made around that time, though he declined and gave Caesar no warning. By February 44 BC, there were some sixty conspirators.[214] It is clear that by this time, the victorious Caesarian coalition from the civil war had broken apart.[215] While most of the conspirators were former Pompeians, they were joined by a substantial number of Caesarians.[216] Among their leaders were Gaius Trebonius (consul in 45), Decimus Brutus (consul designate for 42), as well as Cassius and Brutus (both praetors in 44 BC).[217] Trebonius and Decimus had joined Caesar during the war while Brutus and Cassius had joined Pompey; other Caesarians involved included Servius Sulpicius Galba, Lucius Minucius Basilus, Lucius Tullius Cimber, and Gaius Servilius Casca.[218] Many of the conspirators would have been candidates in the consular elections for 43 to 41 BC,[219] likely dismayed by Caesar's sham elections in early 44 BC that produced advance results for the years 43–41 BC. Those electoral results came from the grace of the dictator and not that of the people; for the republican elite this was no substitute for actual popular support.[220] Nor is it likely that the subordination of the normal magistrates to Caesar's masters of horse (Latin: magistri equitum) was appreciated.[221]

Brutus, who claimed descent from the Lucius Junius Brutus who had driven out the kings and the Gaius Servilius Ahala who had freed Rome from incipient tyranny, was the main leader of the conspiracy.[222] By late autumn 45 BC, graffiti[223] and some public comments at Rome were condemning Caesar as a tyrant and insinuating the need for a Brutus to remove the dictator. The ancient sources, excepting Nicolaus of Damascus, are unanimous that this reflected a genuine turn in public opinion against Caesar.[224] Popular indignation at Caesar was likely rooted in his debt policies (too friendly to lenders), use of lethal force to suppress protests for debt relief, his reduction in the grain dole, his abolition of the collegia restored by Clodius, his abolition of the poorest panel of jurors in the permanent courts, and his abolition of open elections which deprived the people of their ancient right of decision.[225] A popular turn against Caesar is also observed with reports that the two deposed tribunes were written-in on ballots at Caesar's advance consular elections in place of Caesar's candidates.[226] Whether there was a tradition of tyrannicide at Rome is unclear: Cicero wrote in private as if the duty to kill tyrants was already given; he, however, made no public speeches to that effect and there is little evidence that the public accepted the logic of preventive tyrannicide.[227] The philosophical tradition of the Platonic Old Academy was also a factor driving Brutus to action due to its emphasis on a duty to free the state from tyranny.[228]

While some news of the conspiracy did leak out, Caesar refused to take precautions and rejected escort by a bodyguard. The date decided upon by the conspirators was 15 March, the Ides of March, three days before Caesar intended to leave for his Parthian campaign.[229] News of his imminent departure forced the conspirators to move up their plans; the Senate meeting on the 15th would be the last before his departure.[230] They had decided that a Senate meeting was the best place to frame the killing as political, rejecting the alternatives at games, elections, or on the road.[231] That only the conspirators would be armed at the Senate meeting, per Dio, also would have been an advantage. The day, 15 March, was also symbolically important as it was the day on which consuls took office until the mid-2nd century BC.[232]

Various stories purport that Caesar was on the cusp of not attending or otherwise being warned about the plot.[232][233] Approached on his golden chair at the foot of the statue of Pompey, the conspirators attacked him with daggers. Whether he fell in silence, per Suetonius, or after reply to Brutus' appearance – kai su teknon? ("you too, child?") – is variantly recorded.[234] Between twenty-three and thirty-five wounds later, the dictator-for-life was dead.[235][236]

Aftermath of the assassination

The assassins seized the Capitoline hill after killing the dictator. They then summoned a public meeting in the Forum where they were coldly received by the population. They were also unable to fully secure the city, as Lepidus – Caesar's lieutenant in the dictatorship – moved troops from the Tiber Island into the city proper. Antony, the consul who escaped the assassination, urged an illogical compromise position in the Senate:[237] Caesar was not declared a tyrant and the conspirators were not punished.[238]

Caesar's funeral was then approved. At the funeral, Antony inflamed the public against the assassins, which triggered mob violence that lasted for some months before the assassins were forced to flee the capital and Antony then finally acted to suppress it by force.[239] On the site of his cremation, the Temple of Caesar was begun by the triumvirs in 42 BC at the east side of the main square of the Roman Forum. Only its altar now remains.[240] The terms of the will were also read to the public: it gave a generous donative to the plebs at large and left as principal heir one Gaius Octavius, Caesar's great-nephew then at Apollonia, and adopted him in the will.[241]

Resumption of the pre-existing republic proved impossible as various actors appealed in the aftermath of Caesar's death to liberty or to vengeance to mobilise huge armies that led to a series of civil wars.[242] The first war was between Antony in 43 BC and the Senate (including senators of both Caesarian and Pompeian persuasion) which resulted in Octavian – Caesar's heir – exploiting the chaos to seize the consulship and join with Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate.[243] After purging their political enemies in a series of proscriptions,[244] the triumvirs secured the deification of Caesar – the Senate declared on 1 January 42 BC that Caesar would be placed among the Roman gods[245] – and marched on the east where a second war saw the triumvirs defeat the tyrannicides in battle,[246] resulting in a final death of the republican cause and a three-way division of much of the Roman world.[247] By 31 BC, Caesar's heir had taken sole control of the empire, ejecting his triumviral rivals after two decades of civil war. Pretending to restore the republic, his masked autocracy was acceptable to the war-weary Romans and marked the establishment of a new Roman monarchy.[248]

Personal life

Health and physical appearance

.jpg.webp)

Based on remarks by Plutarch,[249] Caesar is sometimes thought to have suffered from epilepsy. Modern scholarship is sharply divided on the subject, and some scholars believe that he was plagued by malaria, particularly during the Sullan proscriptions of the 80s BC.[250] Other scholars contend his epileptic seizures were due to a parasitic infection in the brain by a tapeworm.[251][252]

Caesar had four documented episodes of what may have been complex partial seizures. He may additionally have had absence seizures in his youth. The earliest accounts of these seizures were made by the biographer Suetonius, who was born after Caesar died. The claim of epilepsy is countered among some medical historians by a claim of hypoglycemia, which can cause epileptoid seizures.[253][254]

A line from Shakespeare has sometimes been taken to mean that he was deaf in one ear: "Come on my right hand, for this ear is deaf".[255] No classical source mentions hearing impairment in connection with Caesar. The playwright may have been making metaphorical use of a passage in Plutarch that does not refer to deafness at all, but rather to a gesture Alexander of Macedon customarily made. By covering his ear, Alexander indicated that he had turned his attention from an accusation in order to hear the defence.[256]

Francesco M. Galassi and Hutan Ashrafian suggest that Caesar's behavioral manifestations – headaches, vertigo, falls (possibly caused by muscle weakness due to nerve damage), sensory deficit, giddiness and insensibility – and syncopal episodes were the results of cerebrovascular episodes, not epilepsy. Pliny the Elder reports in his Natural History that Caesar's father and forefather died without apparent cause while putting on their shoes.[257] These events can be more readily associated with cardiovascular complications from a stroke episode or lethal heart attack. Caesar possibly had a genetic predisposition for cardiovascular disease.[258]

Suetonius, writing more than a century after Caesar's death, describes Caesar as "tall of stature with a fair complexion, shapely limbs, a somewhat full face, and keen black eyes".[259]

The name Gaius Julius Caesar

Using the Latin alphabet of the period, which lacked the letters J and U, Caesar's name would be rendered GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR; the form CAIVS is also attested, using the older Roman representation of G by C. The standard abbreviation was C. IVLIVS CÆSAR, reflecting the older spelling. (The letterform Æ is a ligature of the letters A and E, and is often used in Latin inscriptions to save space.)

In Classical Latin, it was pronounced [ˈɡaː.i.ʊs ˈjuːl.i.ʊs ˈkae̯sar]. In the days of the late Roman Republic, many historical writings were done in Greek, a language most educated Romans studied. Young wealthy Roman boys were often taught by Greek slaves and sometimes sent to Athens for advanced training, as was Caesar's principal assassin, Brutus. In Greek, during Caesar's time, his family name was written Καίσαρ (Kaísar), reflecting its contemporary pronunciation. Thus, his name is pronounced in a similar way to the pronunciation of the German Kaiser ([kaɪ̯zɐ]) or Dutch keizer ([kɛizɛr]).

In Vulgar Latin, the original diphthong [ae̯] first began to be pronounced as a simple long vowel [ɛː]. Then, the plosive /k/ before front vowels began, due to palatalization, to be pronounced as an affricate, hence renderings like [ˈtʃeːsar] in Italian and [ˈtseːzar] in German regional pronunciations of Latin, as well as the title of Tsar. With the evolution of the Romance languages, the affricate [ts] became a fricative [s] (thus, [ˈseːsar]) in many regional pronunciations, including the French one, from which the modern English pronunciation is derived.

Caesar's cognomen itself became a title; it was promulgated by the Bible, which contains the famous verse "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's". The title became, from the late first millennium, Kaiser in German and (through Old Church Slavic cěsarĭ) Tsar or Czar in the Slavic languages. The last Tsar in nominal power was Simeon II of Bulgaria, whose reign ended in 1946, but is still alive in 2023. This means that for approximately two thousand years, there was at least one head of state bearing his name. As a term for the highest ruler, the word Caesar constitutes one of the earliest, best attested and most widespread Latin loanwords in the Germanic languages, being found in the text corpora of Old High German (keisar), Old Saxon (kēsur), Old English (cāsere), Old Norse (keisari), Old Dutch (keisere) and (through Greek) Gothic (kaisar).[260]

Posterity

- Wives

- First marriage to Cornelia, from 84 BC until her death in 69 BC

- Second marriage to Pompeia, from 67 BC until he divorced her around 61 BC over the Bona Dea scandal

- Third marriage to Calpurnia, from 59 BC until Caesar's death

- Children

- Julia, by Cornelia, born in 83 or 82 BC

- Caesarion, by Cleopatra VII, born 47 BC, and killed at age 17 by Caesar's adopted son Octavianus.

- Posthumously adopted: Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, his great-nephew by blood (grandson of Julia, his sister), who later became Emperor Augustus.

- Suspected children

Some ancient sources refer to the possibility of the tyrannicide, Marcus Junius Brutus, being one of Julius Caesar's illegitimate children.[262] Caesar, at the time Brutus was born, was 15. Most ancient historians were sceptical of this and "on the whole, scholars have rejected the possibility that Brutus was the love-child of Servilia and Caesar on the grounds of chronology".[263][264][265]

- Grandchildren

Grandchild from Julia and Pompey, dead at several days, unnamed.[266]

- Lovers

Rumors of passive homosexuality

Roman society viewed the passive role during sexual activity, regardless of gender, to be a sign of submission or inferiority. Indeed, Suetonius says that in Caesar's Gallic triumph, his soldiers sang that, "Caesar may have conquered the Gauls, but Nicomedes conquered Caesar."[267] According to Cicero, Bibulus, Gaius Memmius, and others – mainly Caesar's enemies – he had an affair with Nicomedes IV of Bithynia early in his career. The stories were repeated, referring to Caesar as the "Queen of Bithynia", by some Roman politicians as a way to humiliate him. Caesar himself denied the accusations repeatedly throughout his lifetime, and according to Cassius Dio, even under oath on one occasion.[268] This form of slander was popular during this time in the Roman Republic to demean and discredit political opponents.

Catullus wrote a poem suggesting that Caesar and his engineer Mamurra were lovers,[269] but later apologised.[270]

Mark Antony charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favors. Suetonius described Antony's accusation of an affair with Octavian as political slander. Octavian eventually became the first Roman Emperor as Augustus.[271]

Literary works

During his lifetime, Caesar was regarded as one of the best orators and prose authors in Latin – even Cicero spoke highly of Caesar's rhetoric and style.[272] Only Caesar's war commentaries have survived. A few sentences from other works are quoted by other authors. Among his lost works are his funeral oration for his paternal aunt Julia and his "Anticato", a document attacking Cato in response to Cicero's eulogy. Poems by Julius Caesar are also mentioned in ancient sources.[273]

Memoirs

- The Commentarii de Bello Gallico, usually known in English as The Gallic Wars, seven books each covering one year of his campaigns in Gaul and southern Britain in the 50s BC, with the eighth book written by Aulus Hirtius on the last two years.

- The Commentarii de Bello Civili (The Civil War), events of the Civil War from Caesar's perspective, until immediately after Pompey's death in Egypt.

Other works historically have been attributed to Caesar, but their authorship is in doubt:

- De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria;

- De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa; and

- De Bello Hispaniensi (On the Hispanic War), campaigns in the Iberian Peninsula.

These narratives were written and published annually during or just after the actual campaigns, as a sort of "dispatches from the front". They were important in shaping Caesar's public image and enhancing his reputation when he was away from Rome for long periods. They may have been presented as public readings.[274] As a model of clear and direct Latin style, The Gallic Wars traditionally has been studied by first- or second-year Latin students.

Legacy

Historiography

The texts written by Caesar, an autobiography of the most important events of his public life, are the most complete primary source for the reconstruction of his biography. However, Caesar wrote those texts with his political career in mind.[275] Julius Caesar is also considered one of the first historical figures to fold his message scrolls into a concertina form, which made them easier to read.[276] The Roman emperor Augustus began a cult of personality of Caesar, which described Augustus as Caesar's political heir. The modern historiography is influenced by this tradition.[277]

Many rulers in history became interested in the historiography of Caesar. Napoleon III wrote the scholarly work Histoire de Jules César, which was not finished. The second volume listed previous rulers interested in the topic. Charles VIII ordered a monk to prepare a translation of the Gallic Wars in 1480. Charles V ordered a topographic study in France, to place the Gallic Wars in context; which created forty high-quality maps of the conflict. The contemporary Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent catalogued the surviving editions of the Commentaries, and translated them to Turkish language. Henry IV and Louis XIII of France translated the first two commentaries and the last two respectively; Louis XIV retranslated the first one afterwards.[278]

Politics

Julius Caesar is seen as the main example of Caesarism, a form of political rule led by a charismatic strongman whose rule is based upon a cult of personality, whose rationale is the need to rule by force, establishing a violent social order, and being a regime involving prominence of the military in the government.[279] Other people in history, such as the French Napoleon Bonaparte and the Italian Benito Mussolini, have defined themselves as Caesarists.[280][281] Bonaparte did not focus only on Caesar's military career but also on his relation with the masses, a predecessor to populism.[282] The word is also used in a pejorative manner by critics of this type of political rule.

Depictions

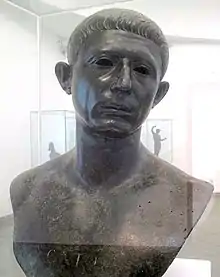

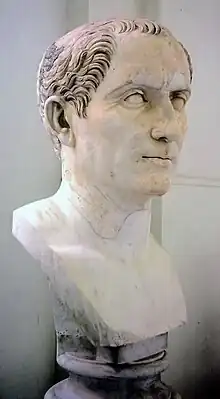

Bust in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples

Bust in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples Modern bronze statue of Julius Caesar, Rimini, Italy

Modern bronze statue of Julius Caesar, Rimini, Italy_at_the_Archaeological_Museum_of_Sparta_on_15_May_2019.jpg.webp) Portrait at the Archaeological Museum of Sparta

Portrait at the Archaeological Museum of Sparta Bronze statue at the Porta Palatina in Turin

Bronze statue at the Porta Palatina in Turin_at_the_Archaeological_Museum_of_Corinth_on_10_January_2020.jpg.webp) Bust in the Archaeological Museum of Corinth

Bust in the Archaeological Museum of Corinth.JPG.webp) Bust in Naples National Archaeological Museum, photograph published in 1902

Bust in Naples National Archaeological Museum, photograph published in 1902

Battle record

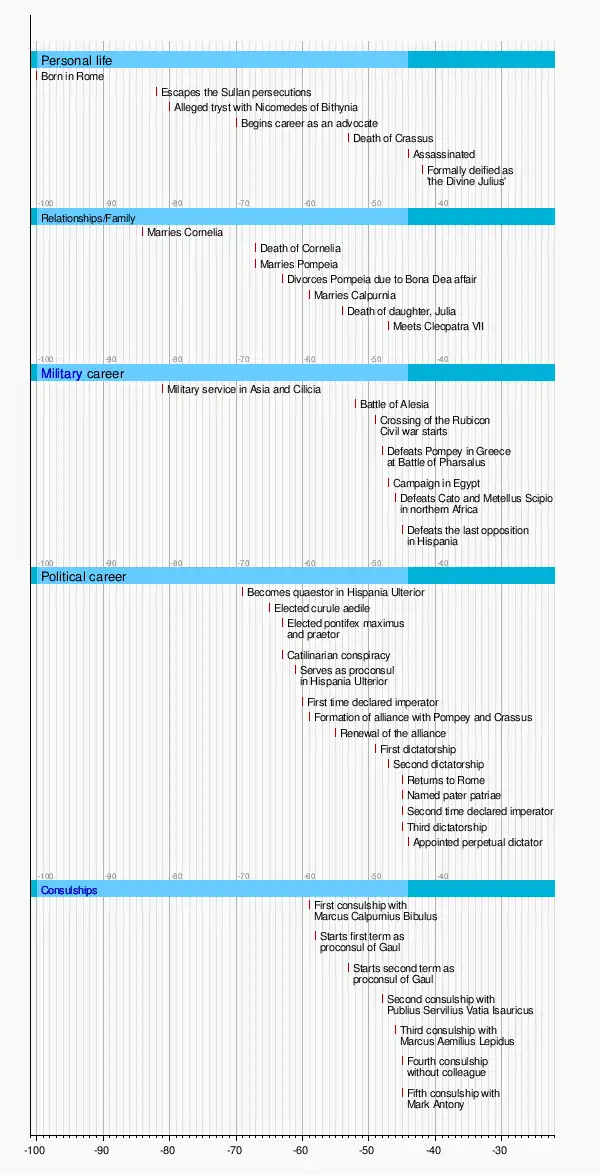

Chronology

See also

- Et tu, Brute?

- Julius Caesar, a play by William Shakespeare (c. 1599)

- Giulio Cesare, an opera by Handel, 1724

- Veni, vidi, vici

- Caesar cipher

- Caesareum of Alexandria

References

- Badian 2009, p. 16. All ancient sources place his birth in 100 BC. Some historians have argued against this; the "consensus of opinion" places it in 100 BC. Goldsworthy 2006, p. 30.

- Broughton 1952, p. 574.

- Keppie, Lawrence (1998). "The approach of civil war". The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8061-3014-9.

- Tucker, Spencer (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-59884-430-6.

- Badian 2009, p. 16, pursuant to Macr. Sat. 1.12.34, quoting a law by Mark Antony noting the date as the fourth day before the Ides of Quintilis. Only Dio gives 13 July. All sources give the year 100 BC.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 32–33.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 35.

- Badian 2009, p. 14; Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 31–32. The consul of 157 BC was Sextus Caesar; the consuls of 91 and 90 were Sextus Caesar and Lucius Caesar, respectively.

- Badian 2009, p. 15 dates the land commission to 103 per MRR 3.109; Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 33–34; Broughton 1952, p. 22, dating the proconsulship to 91 with praetorship in 92 BC and citing, among others, CIL I, 705 and CIL I, 706.

- Badian 2009, p. 16.

- Badian 2009, p. 16. Badian cites Suet. Iul., 1.2 arguing that Caesar was actually appointed; because a divorced man could not be flamen Dialis, the assertion that Caesar married one Cossutia then divorced her to marry Cornelia and become flamen in Plut. Caes., 5.3 is incorrect.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 34.

- Badian 2009, pp. 16–17, stating Caesar was placed on the lists. Cf, stating Caesar was only summoned for interrogation, Hinard, François (1985). Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (in French). Ecole française de Rome. p. 64. ISBN 978-2-7283-0094-5. OCLC 1006100534.

- Badian 2009, pp. 16–17, also rejecting claims that Caesar hid by bribing his pursuers: "this is an example of how the [Caesar myth] pervades our accounts and makes it difficult to get at the facts... [that he bribed his pursuers] cannot be true, since confiscation of his fortune went with his proscription".

- Plut. Caes., 1.4; Suet. Iul., 1.3.

- Badian 2009, p. 17, noting also that Sulla never killed any fellow patricians.

- Badian 2009, pp. 17–18.

- Suet. Iul., 2–3; Plut. Caes., 2–3; Dio, 43.20.

- Badian 2009, p. 17.

- Badian 2009, p. 18, citing Suet. Iul., 3.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 35.

- Alexander 1990, p. 71 (Trial 140) noting also that Tac. Dial., 34.7 wrongly places the trial in 79 BC; Alexander 1990, pp. 71–72 (Trial 141).

- Badian 2009, p. 18.

- Pelling, C B R (2011). Plutarch: Caesar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 139–41. ISBN 978-0-19-814904-0. OCLC 772240772. Pelling agrees with Vell. Pat., 2.42.3 over Plut. Caes., 1.8–2.7 and Suet. Iul., 4.

- Badian 2009, p. 19, calling the story in Suet. Iul., 4.2 that Caesar called up auxiliaries and with them drove Mithridates' prefect from the province of Asia, "a striking example of the Caesar myth... [that is] difficult to believe".

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 78.

- Badian 2009, p. 19; Broughton 1952, pp. 114, 125; Vell. Pat., 2.43.1 (pontificate); Plut. Caes., 5.1 and Suet. Iul., 5 (military tribunate).

- Badian 2009, p. 19, citing Suet. Iul., 5.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 63.

- Badian 2009, pp. 19–20, also noting senatorial support for the pardons; Broughton 1952, pp. 126, 128, 130 n. 4, argues the tribunician law recalling the Lepidan exiles must postdate the consular law in 70 which removed Sulla's suppression of tribunician legislative initiative.

- Badian 2009, p. 20; Broughton 1952, p. 132. Badian 2009, p. 21 cites Suet. Iul., 6.1 for the incipit of Caesar's eulogy.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 43.

- Plut. Caes., 5.2–3.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 43–46.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 46, noting also that Plutarch omits this detail likely because it "would indeed have been embarrassing for his Marian representation of Caesar" (internal citations and quotation marks omitted).

- Gruen 1995, p. 79–80.

- Mouritsen, Henrik (2001). Plebs and politics in the late Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-511-04114-4. OCLC 56761502. See also Broughton 1952, p. 158 and Plut. Caes., 6.1–4.

- Broughton 1952, p. 158.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 46–47.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 48–49.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 64, 64 n. 129, noting that it is not clear which election was first; it is more likely, however, that elections were late and therefore that the pontifical election occurred first. Dio's claim of elections in December is clearly erroneous. Broughton 1952, p. 172 n. 3.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 64–65, noting the victory of curule aedile Publius Licinius Crassus in 212 over senior consulars and plebeian tribune Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus over consulars.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 66, citing Suet. Iul., 13; Plut. Caes., 7.1–4; Dio, 37.37.1–3.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 67–68.

- Gruen 1995, pp. 80–81.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 69 n. 148.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 71.

- Alexander 1990, p. 110 (Trials 220–21).

- Gruen 1995, p. 80, citing Sall. Cat., 49.1–2. See also Suet. Iul., 17.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 72–77, placing it around 2.5 per cent. Gruen 1995, p. 429 n. 107 calls the view that Caesar was one of the masterminds of the conspiracy "long... discredited and requires no further refutation".

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 85–86, 90.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 92. Earlier sources being Cic. Cat., 4.8–10 and Sall. Cat., 51.42. Later sources include Plut. Caes., 7.9 and App. BCiv., 2.6.

- Gruen 1995, pp. 281–82.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 102.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 102–04.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 107, citing Suet. Iul., 16. Dio reports a senatus consultum ultimum. Broughton 1952, p. 173, citing Dio, 37.41.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 109.

- Plut. Caes., 10.9.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 110, adding in notes that the affair is usually interpreted as an attempt to destroy Clodius' career and that Caesar may have been a secondary target due to expectations that he would reject political pressure for a divorce.

- Drogula 2019, pp. 97–98.

- Broughton 1952, pp. 173, 180. Most sources give a proconsular dignity. After the Sullan era, all magistrates were prorogued pro consule. Badian, Ernst; Lintott, Andrew (2016). "pro consule, pro praetore". Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5337. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 109–10.

- Broughton 1952, p. 180.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 110–11.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 111.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 112–13.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 114; Plut. Caes., 13; Suet. Iul., 18.2.

- Gruen 2009, p. 28.

- Gruen 2009, pp. 30–31.

- Gruen 2009, p. 28; Broughton 1952, pp. 158, 173. Bibulus was Caesar's colleague both in the curule aedileship and the praetorship. They clashed politically in both magistracies. On credit for the aedilican games, see Suet. Iul., 10, Dio, 37.8.2, and Plut. Caes., 5.5.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 119. "[A]n alliance which in modern times has come, quite misleadingly, to be called the 'First Triumvirate'... the very phrase... invokes a misleading teleology. Furthermore, it is almost impossible to use [it] without adopting some version of the view that it was a kind of conspiracy against the republic".

- Gruen 2009, p. 31.

- Gruen 2009, p. 31; Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 121–22, noting that the Senate had approved distribution of lands to Pompey's veterans from the Sertorian War all the way back in 70 BC.

- Gruen 2009, p. 32.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 125–29.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 130, 132.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 138.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 139–40.

- Wiseman 1994, p. 372.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 143 (Bibulus), 147 (dating to May).

- Wiseman 1994, p. 374.

- Drogula 2019, p. 137.

- Gruen 2009, p. 33, noting that the lex Vatinia was "no means unprecedented... or even controversial".

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 175, citing Balsdon, J P V D (1939). "Consular provinces under the late Republic – II. Caesar's Gallic command". Journal of Roman Studies. 29: 167–83. doi:10.2307/297143. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 297143. S2CID 163892529. Moreover, Caesar's eventual provinces of Trans- and Cisalpine Gaul had been assigned to the consuls of 60 and therefore would have been unavailable. Rafferty, David (2017). "Cisalpine Gaul as a consular province in the late Republic". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 66 (2): 147–172. doi:10.25162/historia-2017-0008. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 45019257. S2CID 231088284.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 176–77; Gruen 2009, p. 34.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 143: Dio, 38.6.5 and Suet. Iul., 20.1 say around late January; Plut. Pomp., 48.5 says in early May; Vell. Pat., 2.44.5 says May.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 142–44.

- Gruen 2009, p. 34, also citing Suet. Iul., 20.2 – the "consulship of Julius and Caesar" – as part of Catonian propaganda.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 150–51, noting that Bibulus' voluntary seclusion "presented the image of the city dominated by one man [Caesar]... unchecked by a colleague".

- Gruen 2009, p. 34.

- Drogula 2019, pp. 138–39, noting Cato's support of Caesar's anti-corruption bill and the possibility that Cato gave input for some of its provisions.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 182–83, 182 n. 260, citing Suet. Iul., 23.1; pace Ramsey 2009, p. 38.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 186–87.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 188–89.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 189–90.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 204.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 205, 208–10.

- Goldsworthy 2016, pp. 212–15.

- Goldsworthy 2016, p. 217.

- Goldsworthy 2016, p. 220.

- Boatwright 2004, p. 242.

- Goldsworthy 2016, p. 203.

- Goldsworthy 2016, pp. 221–22; Boatwright 2004, p. 242.

- Goldsworthy 2016, p. 222.

- Goldsworthy 2016, p. 223.

- Goldsworthy 2016, pp. 229–32, 233–38; Boatwright 2004, p. 242.

- Gruen 1995, p. 98. "It should no longer be necessary to refute the older notion that Clodius acted as agent or tool of the triumvirate". Clodius was an independent agent not beholden to the triumvirs or any putative popular party. Gruen, Erich S (1966). "P. Clodius: Instrument or Independent Agent?". Phoenix. 20 (2): 120–30. doi:10.2307/1086053. ISSN 0031-8299. JSTOR 1086053.

- Ramsey 2009, pp. 37–38.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 194, noting Caesar's opposition – in early 58 BC – to Cicero's banishment. Caesar offered Cicero a position on his staff which would have conferred immunity from prosecution but Cicero refused. Ramsey 2009, p. 37.

- Ramsey 2009, p. 39.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 220, citing Gelzer, "this extraordinary honour... cut the ground from under the feet of those who maintained that since 58 Caesar had held his position illegally"; Morstein-Marx also rejects the claim of senatorial duress at Plut. Caes., 21.7–9.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 196, 220; Ramsey 2009, pp. 39–40.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 220–21.

- Ramsey 2009, pp. 39–40.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 229.

- Ramsey 2009, pp. 41–42; Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 232.

- Ramsey 2009, p. 43; Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 232–33.

- Ramsey 2009, p. 44; Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 232–33.

- Gruen 1995, p. 451.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 238, citing Cic. Sest., 51, "hardly anyone has lost popularity among the citizens for winning wars".

- Ramsey 2009, p. 44.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 241ff, citing Caes. BGall., 5.26–52.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 272 n. 42: "Gruen.. and Raaflaub... have effectively disposed of the old idea, too heavily influenced by [Plutarch]", citing Plut. Caes., 28.1 and Plut. Pomp., 53.6–54.2, "that Pompey had now turned against Caesar... since Julia's death in 54".

- Ramsey 2009, p. 46: "Despite the fact that Pompey declined Caesar's later offer to form another marriage connection, their political alliance showed no signs of strain for the next several years".

- Gruen 1995, pp. 451–52, 453: "Julia's death came in the late summer of 54[;] if it opened a breach between Pompey and Caesar, there is no sign of it in subsequent months... The evidence indicates no change in the relationship during 53"; "Julia's death provoked no change in the contract[;] Caesar did not cut Pompey out of his will until the outbreak of civil war".

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 243–44.

- Ramsey, J T (2016). "How and why was Pompey made sole consul in 52 BC?". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 65 (3): 298–324. doi:10.25162/historia-2016-0017. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 45019234. S2CID 252459421.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 247–48, 260, 265–66.

- Wiseman 1994, p. 412.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 258. See also Appendix 4 in the same book, analysing the conflict between Caesar and Pompey in terms of a Prisoner's dilemma.

- Wiseman 1994, p. 414, citing Caes. BGall., 8.2–16.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 270; Drogula 2019, p. 223.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 273.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 272, 276, 295 (identities of Cato's allies).

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 291.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 292–93.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 297.

- Wiseman 1994, pp. 412–22, citing App. BCiv., 2.30–31 and Dio, 40.64.1–66.5.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 304.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 306.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 308.

- Boatwright 2004, p. 247; Meier 1995, pp. 1, 4; Mackay 2009, pp. 279–81; Wiseman 1994, p. 419.

- Ehrhardt, C T H R (1995). "Crossing the Rubicon". Antichthon. 29: 30–41. doi:10.1017/S0066477400000927. ISSN 0066-4774. S2CID 142429003. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.