Catalytic triad

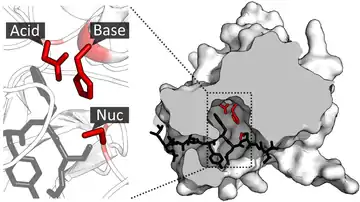

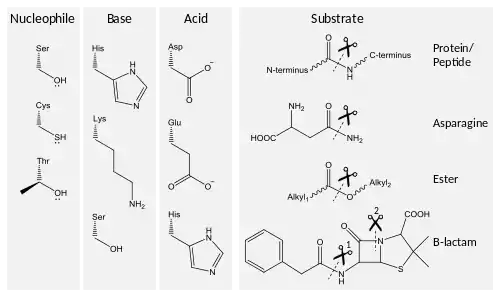

A catalytic triad is a set of three coordinated amino acids that can be found in the active site of some enzymes.[1][2] Catalytic triads are most commonly found in hydrolase and transferase enzymes (e.g. proteases, amidases, esterases, acylases, lipases and β-lactamases). An acid-base-nucleophile triad is a common motif for generating a nucleophilic residue for covalent catalysis. The residues form a charge-relay network to polarise and activate the nucleophile, which attacks the substrate, forming a covalent intermediate which is then hydrolysed to release the product and regenerate free enzyme. The nucleophile is most commonly a serine or cysteine amino acid, but occasionally threonine or even selenocysteine. The 3D structure of the enzyme brings together the triad residues in a precise orientation, even though they may be far apart in the sequence (primary structure).[3]

As well as divergent evolution of function (and even the triad's nucleophile), catalytic triads show some of the best examples of convergent evolution. Chemical constraints on catalysis have led to the same catalytic solution independently evolving in at least 23 separate superfamilies.[2] Their mechanism of action is consequently one of the best studied in biochemistry.[4][5]

History

The enzymes trypsin and chymotrypsin were first purified in the 1930s.[6] A serine in each of trypsin and chymotrypsin was identified as the catalytic nucleophile (by diisopropyl fluorophosphate modification) in the 1950s.[7] The structure of chymotrypsin was solved by X-ray crystallography in the 1960s, showing the orientation of the catalytic triad in the active site.[8] Other proteases were sequenced and aligned to reveal a family of related proteases,[9][10][11] now called the S1 family. Simultaneously, the structures of the evolutionarily unrelated papain and subtilisin proteases were found to contain analogous triads. The 'charge-relay' mechanism for the activation of the nucleophile by the other triad members was proposed in the late 1960s.[12] As more protease structures were solved by X-ray crystallography in the 1970s and 80s, homologous (such as TEV protease) and analogous (such as papain) triads were found.[13][14][15] The MEROPS classification system in the 1990s and 2000s began classing proteases into structurally related enzyme superfamilies and so acts as a database of the convergent evolution of triads in over 20 superfamilies.[16][17] Understanding how chemical constraints on evolution led to the convergence of so many enzyme families on the same triad geometries has developed in the 2010s.[2]

Since their initial discovery, there have been increasingly detailed investigations of their exact catalytic mechanism. Of particular contention in the 1990s and 2000s was whether low-barrier hydrogen bonding contributed to catalysis,[18][19][20] or whether ordinary hydrogen bonding is sufficient to explain the mechanism.[21][22] The massive body of work on the charge-relay, covalent catalysis used by catalytic triads has led to the mechanism being the best characterised in all of biochemistry.[4][5][21]

Function

Enzymes that contain a catalytic triad use it for one of two reaction types: either to split a substrate (hydrolases) or to transfer one portion of a substrate over to a second substrate (transferases). Triads are an inter-dependent set of residues in the active site of an enzyme and act in concert with other residues (e.g. binding site and oxyanion hole) to achieve nucleophilic catalysis. These triad residues act together to make the nucleophile member highly reactive, generating a covalent intermediate with the substrate that is then resolved to complete catalysis.

Mechanism

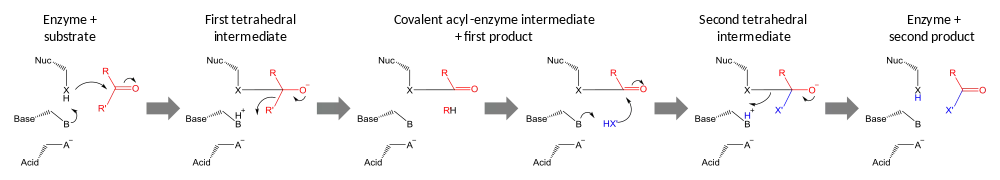

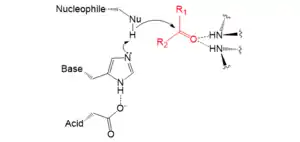

Catalytic triads perform covalent catalysis using a residue as a nucleophile. The reactivity of the nucleophilic residue is increased by the functional groups of the other triad members. The nucleophile is polarised and oriented by the base, which is itself bound and stabilised by the acid.

Catalysis is performed in two stages. First, the activated nucleophile attacks the carbonyl carbon and forces the carbonyl oxygen to accept an electron pair, leading to a tetrahedral intermediate. The build-up of negative charge on this intermediate is typically stabilized by an oxyanion hole within the active site. The intermediate then collapses back to a carbonyl, ejecting the first half of the substrate, but leaving the second half still covalently bound to the enzyme as an acyl-enzyme intermediate. Although general-acid catalysis for breakdown of the First and Second tetrahedral intermediate may occur by the path shown in the diagram, evidence supporting this mechanism with chymotrypsin[23] has been controverted.[24]

The second stage of catalysis is the resolution of the acyl-enzyme intermediate by the attack of a second substrate. If this substrate is water then the result is hydrolysis; if it is an organic molecule then the result is transfer of that molecule onto the first substrate. Attack by this second substrate forms a new tetrahedral intermediate, which resolves by ejecting the enzyme's nucleophile, releasing the second product and regenerating free enzyme.[25]

Identity of triad members

Nucleophile

The side-chain of the nucleophilic residue performs covalent catalysis on the substrate. The lone pair of electrons present on the oxygen or sulfur attacks the electropositive carbonyl carbon.[3] The 20 naturally occurring biological amino acids do not contain any sufficiently nucleophilic functional groups for many difficult catalytic reactions. Embedding the nucleophile in a triad increases its reactivity for efficient catalysis. The most commonly used nucleophiles are the hydroxyl (OH) of serine and the thiol/thiolate ion (SH/S−) of cysteine.[2] Alternatively, threonine proteases use the secondary hydroxyl of threonine, however due to steric hindrance of the side chain's extra methyl group such proteases use their N-terminal amide as the base, rather than a separate amino acid.[1][26]

Use of oxygen or sulfur as the nucleophilic atom causes minor differences in catalysis. Compared to oxygen, sulfur's extra d orbital makes it larger (by 0.4 Å)[27] and softer, allows it to form longer bonds (dC-X and dX-H by 1.3-fold), and gives it a lower pKa (by 5 units).[28] Serine is therefore more dependent than cysteine on optimal orientation of the acid-base triad members to reduce its pKa[28] in order to achieve concerted deprotonation with catalysis.[2] The low pKa of cysteine works to its disadvantage in the resolution of the first tetrahedral intermediate as unproductive reversal of the original nucleophilic attack is the more favourable breakdown product.[2] The triad base is therefore preferentially oriented to protonate the leaving group amide to ensure that it is ejected to leave the enzyme sulfur covalently bound to the substrate N-terminus. Finally, resolution of the acyl-enzyme (to release the substrate C-terminus) requires serine to be re-protonated whereas cysteine can leave as S−. Sterically, the sulfur of cysteine also forms longer bonds and has a bulkier van der Waals radius[2] and if mutated to serine can be trapped in unproductive orientations in the active site.[27]

Very rarely, the selenium atom of the uncommon amino acid selenocysteine is used as a nucleophile.[29] The deprotonated Se− state is strongly favoured when in a catalytic triad.[29]

Base

Since no natural amino acids are strongly nucleophilic, the base in a catalytic triad polarises and deprotonates the nucleophile to increase its reactivity.[3] Additionally, it protonates the first product to aid leaving group departure.

The base is most commonly histidine since its pKa allows for effective base catalysis, hydrogen bonding to the acid residue, and deprotonation of the nucleophile residue.[1] β-lactamases such as TEM-1 use a lysine residue as the base. Because lysine's pKa is so high (pKa=11), a glutamate and several other residues act as the acid to stabilise its deprotonated state during the catalytic cycle.[30][31] Threonine proteases use their N-terminal amide as the base, since steric crowding by the catalytic threonine's methyl prevents other residues from being close enough.[32][33]

Acid

The acidic triad member forms a hydrogen bond with the basic residue. This aligns the basic residue by restricting its side-chain rotation, and polarises it by stabilising its positive charge.[3] Two amino acids have acidic side chains at physiological pH (aspartate or glutamate) and so are the most commonly used for this triad member.[3] Cytomegalovirus protease[lower-alpha 2] uses a pair of histidines, one as the base, as usual, and one as the acid.[1] The second histidine is not as effective an acid as the more common aspartate or glutamate, leading to a lower catalytic efficiency. In some enzymes, the acid member of the triad is less necessary and some act only as a dyad. For example, papain[lower-alpha 3] uses asparagine as its third triad member which orients the histidine base but does not act as an acid. Similarly, hepatitis A virus protease[lower-alpha 4] contains an ordered water in the position where an acid residue should be.

Examples of triads

Ser-His-Asp

The Serine-Histidine-Aspartate motif is one of the most thoroughly characterised catalytic motifs in biochemistry.[3] The triad is exemplified by chymotrypsin,[lower-alpha 5] a model serine protease from the PA superfamily which uses its triad to hydrolyse protein backbones. The aspartate is hydrogen bonded to the histidine, increasing the pKa of its imidazole nitrogen from 7 to around 12. This allows the histidine to act as a powerful general base and to activate the serine nucleophile. It also has an oxyanion hole consisting of several backbone amides which stabilises charge build-up on intermediates. The histidine base aids the first leaving group by donating a proton, and also activates the hydrolytic water substrate by abstracting a proton as the remaining OH− attacks the acyl-enzyme intermediate.

The same triad has also convergently evolved in α/β hydrolases such as some lipases and esterases, however orientation of the triad members is reversed.[34][35] Additionally, brain acetyl hydrolase (which has the same fold as a small G-protein) has also been found to have this triad. The equivalent Ser-His-Glu triad is used in acetylcholinesterase.

Cys-His-Asp

The second most studied triad is the Cysteine-Histidine-Aspartate motif.[2] Several families of cysteine proteases use this triad set, for example TEV protease[lower-alpha 1] and papain.[lower-alpha 3] The triad acts similarly to serine protease triads, with a few notable differences. Due to cysteine's low pKa, the importance of the Asp to catalysis varies and several cysteine proteases are effectively Cys-His dyads (e.g. hepatitis A virus protease), whilst in others the cysteine is already deprotonated before catalysis begins (e.g. papain).[36] This triad is also used by some amidases, such as N-glycanase to hydrolyse non-peptide C-N bonds.[37]

Ser-His-His

The triad of cytomegalovirus protease[lower-alpha 2] uses histidine as both the acid and base triad members. Removing the acid histidine results in only a 10-fold activity loss (compared to >10,000-fold when aspartate is removed from chymotrypsin). This triad has been interpreted as a possible way of generating a less active enzyme to control cleavage rate.[26]

Ser-Glu-Asp

An unusual triad is found in sedolisin proteases.[lower-alpha 6] The low pKa of the glutamate carboxylate group means that it only acts as a base in the triad at very low pH. The triad is hypothesised to be an adaptation to specific environments like acidic hot springs (e.g. kumamolysin) or cell lysosome (e.g. tripeptidyl peptidase).[26]

Cys-His-Ser

The endothelial protease vasohibin[lower-alpha 7] uses a cysteine as the nucleophile, but a serine to coordinate the histidine base.[38][39] Despite the serine being a poor acid, it is still effective in orienting the histidine in the catalytic triad.[38] Some homologues alternatively have a threonine instead of serine at the acid location.[38]

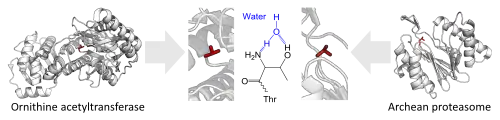

Thr-Nter, Ser-Nter and Cys-Nter

Threonine proteases, such as the proteasome protease subunit[lower-alpha 8] and ornithine acyltransferases[lower-alpha 9] use the secondary hydroxyl of threonine in a manner analogous to the use of the serine primary hydroxyl.[32][33] However, due to the steric interference of the extra methyl group of threonine, the base member of the triad is the N-terminal amide which polarises an ordered water which, in turn, deprotonates the catalytic hydroxyl to increase its reactivity.[1][26] Similarly, there exist equivalent 'serine only' and 'cysteine only' configurations such as penicillin acylase G[lower-alpha 10] and penicillin acylase V[lower-alpha 11] which are evolutionarily related to the proteasome proteases. Again, these use their N-terminal amide as a base.[26]

Ser-cisSer-Lys

This unusual triad occurs only in one superfamily of amidases. In this case, the lysine acts to polarise the middle serine.[40] The middle serine then forms two strong hydrogen bonds to the nucleophilic serine to activate it (one with the side chain hydroxyl and the other with the backbone amide). The middle serine is held in an unusual cis orientation to facilitate precise contacts with the other two triad residues. The triad is further unusual in that the lysine and cis-serine both act as the base in activating the catalytic serine, but the same lysine also performs the role of the acid member as well as making key structural contacts.[40][41]

Sec-His-Glu

The rare, but naturally occurring amino acid selenocysteine (Sec), can also be found as the nucleophile in some catalytic triads.[29] Selenocysteine is similar to cysteine, but contains a selenium atom instead of a sulfur. An example is in the active site of thioredoxin reductase, which uses the selenium for reduction of disulfide in thioredoxin.[29]

Engineered triads

In addition to naturally occurring types of catalytic triads, protein engineering has been used to create enzyme variants with non-native amino acids, or entirely synthetic amino acids.[42] Catalytic triads have also been inserted into otherwise non-catalytic proteins, or protein mimics.

Subtilisin (a serine protease) has had its oxygen nucleophile replaced with each of sulfur,[43][44] selenium,[45] or tellurium.[46] Cysteine and selenocysteine were inserted by mutagenesis, whereas the non-natural amino acid, tellurocysteine, was inserted using auxotrophic cells fed with synthetic tellurocysteine. These elements are all in the 16th periodic table column (chalcogens), so have similar properties.[47][48] In each case, changing the nucleophile reduced the enzyme's protease activity, but increased a different activity. A sulfur nucleophile improved the enzymes transferase activity (sometimes called subtiligase). Selenium and tellurium nucleophiles converted the enzyme into an oxidoreductase.[45][46] When the nucleophile of TEV protease was converted from cysteine to serine, it protease activity was strongly reduced, but was able to be restored by directed evolution.[49]

Non-catalytic proteins have been used as scaffolds, having catalytic triads inserted into them which were then improved by directed evolution. The Ser-His-Asp triad has been inserted into an antibody,[50] as well as a range of other proteins.[51] Similarly, catalytic triad mimics have been created in small organic molecules like diaryl diselenide,[52][53] and displayed on larger polymers like Merrifield resins,[54] and self-assembling short peptide nanostructures.[55]

Divergent evolution

The sophistication of the active site network causes residues involved in catalysis (and residues in contact with these) to be highly evolutionarily conserved.[56] However, there are examples of divergent evolution in catalytic triads, both in the reaction catalysed, and the residues used in catalysis. The triad remains the core of the active site, but it is evolutionarily adapted to serve different functions.[57][58] Some proteins, called pseudoenzymes, have non-catalytic functions (e.g. regulation by inhibitory binding) and have accumulated mutations that inactivate their catalytic triad.[59]

Reaction changes

Catalytic triads perform covalent catalysis via an acyl-enzyme intermediate. If this intermediate is resolved by water, the result is hydrolysis of the substrate. However, if the intermediate is resolved by attack by a second substrate, then the enzyme acts as a transferase. For example, attack by an acyl group results in an acyltransferase reaction. Several families of transferase enzymes have evolved from hydrolases by adaptation to exclude water and favour attack of a second substrate.[60] In different members of the α/β-hydrolase superfamily, the Ser-His-Asp triad is tuned by surrounding residues to perform at least 17 different reactions.[35][61] Some of these reactions are also achieved with mechanisms that have altered formation, or resolution of the acyl-enzyme intermediate, or that don't proceed via an acyl-enzyme intermediate.[35]

Additionally, an alternative transferase mechanism has been evolved by amidophosphoribosyltransferase, which has two active sites.[lower-alpha 12] In the first active site, a cysteine triad hydrolyses a glutamine substrate to release free ammonia. The ammonia then diffuses though an internal tunnel in the enzyme to the second active site, where it is transferred to a second substrate.[62][63]

Nucleophile changes

Divergent evolution of active site residues is slow, due to strong chemical constraints. Nevertheless, some protease superfamilies have evolved from one nucleophile to another. This can be inferred when a superfamily (with the same fold) contains families that use different nucleophiles.[49] Such nucleophile switches have occurred several times during evolutionary history, however the mechanisms by which this happen are still unclear.[17][49]

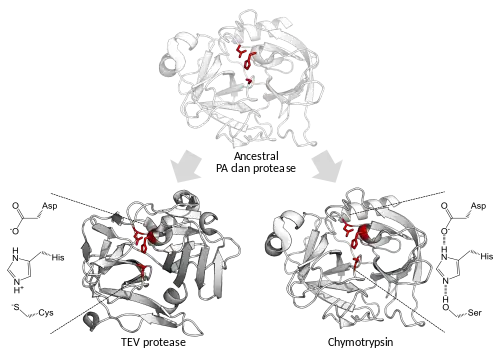

Within protease superfamilies that contain a mixture of nucleophiles (e.g. the PA clan), families are designated by their catalytic nucleophile (C=cysteine proteases, S=serine proteases).

| Superfamily | Families | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PA clan | C3, C4, C24, C30, C37, C62, C74, C99 | TEV protease (Tobacco etch virus) |

| S1, S3, S6, S7, S29, S30, S31, S32, S39, S46, S55, S64, S65, S75 | Chymotrypsin (mammals, e.g. Bos taurus) | |

| PB clan | C44, C45, C59, C69, C89, C95 | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase precursor (Homo sapiens) |

| S45, S63 | Penicillin G acylase precursor (Escherichia coli) | |

| T1, T2, T3, T6 | Archaean proteasome, beta component (Thermoplasma acidophilum) | |

| PC clan | C26, C56 | Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase (Rattus norvegicus) |

| S51 | Dipeptidase E (Escherichia coli) | |

| PD clan | C46 | Hedgehog protein (Drosophila melanogaster) |

| N9, N10, N11 | Intein-containing V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | |

| PE clan | P1 | DmpA aminopeptidase (Brucella anthropi) |

| T5 | Ornithine acetyltransferase precursor (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

Pseudoenzymes

A further subclass of catalytic triad variants are pseudoenzymes, which have triad mutations that make them catalytically inactive, but able to function as binding or structural proteins.[65][66] For example, the heparin-binding protein Azurocidin is a member of the PA clan, but with a glycine in place of the nucleophile and a serine in place of the histidine.[67] Similarly, RHBDF1 is a homolog of the S54 family rhomboid proteases with an alanine in the place of the nucleophilic serine.[68][69] In some cases, pseudoenzymes may still have an intact catalytic triad but mutations in the rest of the protein remove catalytic activity. The CA clan contains catalytically inactive members with mutated triads (calpamodulin has lysine in place of its cysteine nucleophile) and with intact triads but inactivating mutations elsewhere (rat testin retains a Cys-His-Asn triad).[70]

| Superfamily | Families containing pseudoenzymes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CA clan | C1, C2, C19 | Calpamodulin |

| CD clan | C14 | CFLAR |

| SC clan | S9, S33 | Neuroligin |

| SK clan | S14 | ClpR |

| SR clan | S60 | Serotransferrin domain 2 |

| ST clan | S54 | RHBDF1 |

| PA clan | S1 | Azurocidin 1 |

| PB clan | T1 | PSMB3 |

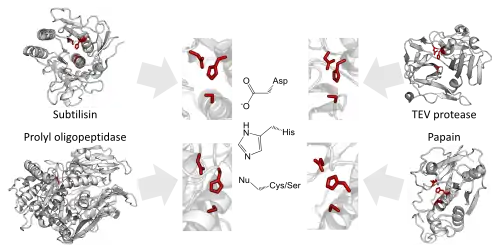

Convergent evolution

The enzymology of proteases provides some of the clearest known examples of convergent evolution. The same geometric arrangement of triad residues occurs in over 20 separate enzyme superfamilies. Each of these superfamilies is the result of convergent evolution for the same triad arrangement within a different structural fold. This is because there are limited productive ways to arrange three triad residues, the enzyme backbone and the substrate. These examples reflect the intrinsic chemical and physical constraints on enzymes, leading evolution to repeatedly and independently converge on equivalent solutions.[1][2]

Cysteine and serine hydrolases

The same triad geometries been converged upon by serine proteases such as the chymotrypsin[lower-alpha 5] and subtilisin superfamilies. Similar convergent evolution has occurred with cysteine proteases such as viral C3 protease and papain[lower-alpha 3] superfamilies. These triads have converged to almost the same arrangement due to the mechanistic similarities in cysteine and serine proteolysis mechanisms.[2]

Families of cysteine proteases

| Superfamily | Families | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CA | C1, C2, C6, C10, C12, C16, C19, C28, C31, C32, C33, C39, C47, C51, C54, C58, C64, C65, C66, C67, C70, C71, C76, C78, C83, C85, C86, C87, C93, C96, C98, C101 | Papain (Carica papaya) and calpain (Homo sapiens) |

| CD | C11, C13, C14, C25, C50, C80, C84 | Caspase-1 (Rattus norvegicus) and separase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

| CE | C5, C48, C55, C57, C63, C79 | Adenain (human adenovirus type 2) |

| CF | C15 | Pyroglutamyl-peptidase I (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) |

| CL | C60, C82 | Sortase A (Staphylococcus aureus) |

| CM | C18 | Hepatitis C virus peptidase 2 (hepatitis C virus) |

| CN | C9 | Sindbis virus-type nsP2 peptidase (sindbis virus) |

| CO | C40 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase VI (Lysinibacillus sphaericus) |

| CP | C97 | DeSI-1 peptidase (Mus musculus) |

| PA | C3, C4, C24, C30, C37, C62, C74, C99 | TEV protease (Tobacco etch virus) |

| PB | C44, C45, C59, C69, C89, C95 | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase precursor (Homo sapiens) |

| PC | C26, C56 | Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase (Rattus norvegicus) |

| PD | C46 | Hedgehog protein (Drosophila melanogaster) |

| PE | P1 | DmpA aminopeptidase (Brucella anthropi) |

| unassigned | C7, C8, C21, C23, C27, C36, C42, C53, C75 |

Families of serine proteases

| Superfamily | Families | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SB | S8, S53 | Subtilisin (Bacillus licheniformis) |

| SC | S9, S10, S15, S28, S33, S37 | Prolyl oligopeptidase (Sus scrofa) |

| SE | S11, S12, S13 | D-Ala-D-Ala peptidase C (Escherichia coli) |

| SF | S24, S26 | Signal peptidase I (Escherichia coli) |

| SH | S21, S73, S77, S78, S80 | Cytomegalovirus assemblin (human herpesvirus 5) |

| SJ | S16, S50, S69 | Lon-A peptidase (Escherichia coli) |

| SK | S14, S41, S49 | Clp protease (Escherichia coli) |

| SO | S74 | Phage GA-1 neck appendage CIMCD self-cleaving protein (Bacillus phage GA-1) |

| SP | S59 | Nucleoporin 145 (Homo sapiens) |

| SR | S60 | Lactoferrin (Homo sapiens) |

| SS | S66 | Murein tetrapeptidase LD-carboxypeptidase (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) |

| ST | S54 | Rhomboid-1 (Drosophila melanogaster) |

| PA | S1, S3, S6, S7, S29, S30, S31, S32, S39, S46, S55, S64, S65, S75 | Chymotrypsin A (Bos taurus) |

| PB | S45, S63 | Penicillin G acylase precursor (Escherichia coli) |

| PC | S51 | Dipeptidase E (Escherichia coli) |

| PE | P1 | DmpA aminopeptidase (Brucella anthropi) |

| unassigned | S48, S62, S68, S71, S72, S79, S81 |

Threonine proteases

Threonine proteases use the amino acid threonine as their catalytic nucleophile. Unlike cysteine and serine, threonine is a secondary hydroxyl (i.e. has a methyl group). This methyl group greatly restricts the possible orientations of triad and substrate as the methyl clashes with either the enzyme backbone or histidine base.[2] When the nucleophile of a serine protease was mutated to threonine, the methyl occupied a mixture of positions, most of which prevented substrate binding.[71] Consequently, the catalytic residue of a threonine protease is located at its N-terminus.[2]

Two evolutionarily independent enzyme superfamilies with different protein folds are known to use the N-terminal residue as a nucleophile: Superfamily PB (proteasomes using the Ntn fold)[32] and Superfamily PE (acetyltransferases using the DOM fold)[33] This commonality of active site structure in completely different protein folds indicates that the active site evolved convergently in those superfamilies.[2][26]

Families of threonine proteases

| Superfamily | Families | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PB clan | T1, T2, T3, T6 | Archaean proteasome, beta component (Thermoplasma acidophilum) |

| PE clan | T5 | Ornithine acetyltransferase (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) |

See also

References

Notes

- TEV protease MEROPS: clan PA, family C4

- Cytomegalovirus protease MEROPS: clan SH, family S21

- Papain MEROPS: clan CA, family C1

- Hepatitis A virus protease MEROPS: clan PA, family C3

- Chymotrypsin MEROPS: clan PA, family S1

- Sedolisin protease MEROPS: clan SB, family 53

- Vasohibin protease MEROPS: clan CA

- Proteasome MEROPS: clan PB, family T1

- Ornithine acyltransferases MEROPS: clan PE, family T5

- Penicillin acylase G MEROPS: clan PB, family S45

- Penicillin acylase V MEROPS: clan PB, family C59

- amidophosphoribosyltransferase MEROPS: clan PB, family C44

- Subtilisin MEROPS: clan SB, family S8

- Prolyl oligopeptidase MEROPS: clan SC, family S9

Citations

- Dodson G, Wlodawer A (1998). "Catalytic triads and their relatives". Trends Biochem. Sci. 23 (9): 347–52. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01254-7. PMID 9787641.

- Buller AR, Townsend CA (2013). "Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 (8): E653–61. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E.653B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221050110. PMC 3581919. PMID 23382230.

- Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL (2002). "9 Catalytic Strategies". Biochemistry (5th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716749554.

- Perutz M (1992). Protein structure. New approaches to disease and therapy. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 9780716770213.

- Neurath H (1994). "Proteolytic enzymes past and present: the second golden era. Recollections, special section in honor of Max Perutz". Protein Sci. 3 (10): 1734–9. doi:10.1002/pro.5560031013. PMC 2142620. PMID 7849591.

- Ohman KP, Hoffman A, Keiser HR (1990). "Endothelin-induced vasoconstriction and release of atrial natriuretic peptides in the rat". Acta Physiol. Scand. 138 (4): 549–56. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08883.x. PMID 2141214.

- Dixon GH, Kauffman DL, Neurath H (1958). "Amino Acid Sequence in the Region of Diisopropyl Phosphoryl Binding in Dip-Trypsin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (5): 1260–1. doi:10.1021/ja01538a059.

- Matthews BW, Sigler PB, Henderson R, et al. (1967). "Three-dimensional structure of tosyl-α-chymotrypsin". Nature. 214 (5089): 652–656. Bibcode:1967Natur.214..652M. doi:10.1038/214652a0. PMID 6049071. S2CID 4273406.

- Walsh KA, Neurath H (1964). "Trypsinogen and Chymotrypsinogen as Homologous Proteins". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 52 (4): 884–9. Bibcode:1964PNAS...52..884W. doi:10.1073/pnas.52.4.884. PMC 300366. PMID 14224394.

- de Haën C, Neurath H, Teller DC (1975). "The phylogeny of trypsin-related serine proteases and their zymogens. New methods for the investigation of distant evolutionary relationships". J. Mol. Biol. 92 (2): 225–59. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90225-9. PMID 1142424.

- Lesk AM, Fordham WD (1996). "Conservation and variability in the structures of serine proteinases of the chymotrypsin family". J. Mol. Biol. 258 (3): 501–37. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1996.0264. PMID 8642605.

- Blow DM, Birktoft JJ, Hartley BS (1969). "Role of a buried acid group in the mechanism of action of chymotrypsin". Nature. 221 (5178): 337–40. Bibcode:1969Natur.221..337B. doi:10.1038/221337a0. PMID 5764436. S2CID 4214520.

- Gorbalenya AE, Blinov VM, Donchenko AP (1986). "Poliovirus-encoded proteinase 3C: a possible evolutionary link between cellular serine and cysteine proteinase families". FEBS Lett. 194 (2): 253–7. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(86)80095-3. PMID 3000829. S2CID 23268152.

- Bazan JF, Fletterick RJ (1988). "Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (21): 7872–6. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.7872B. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872. PMC 282299. PMID 3186696.

- Phan J, Zdanov A, Evdokimov AG, et al. (2002). "Structural basis for the substrate specificity of tobacco etch virus protease". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (52): 50564–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M207224200. PMID 12377789.

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ (1993). "Evolutionary families of peptidases". Biochem. J. 290 (1): 205–18. doi:10.1042/bj2900205. PMC 1132403. PMID 8439290.

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A (2010). "MEROPS: the peptidase database". Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (supl_1): D227–33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp971. PMC 2808883. PMID 19892822.

- Frey PA, Whitt SA, Tobin JB (1994). "A low-barrier hydrogen bond in the catalytic triad of serine proteases". Science. 264 (5167): 1927–30. Bibcode:1994Sci...264.1927F. doi:10.1126/science.7661899. PMID 7661899.

- Ash EL, Sudmeier JL, De Fabo EC, et al. (1997). "A low-barrier hydrogen bond in the catalytic triad of serine proteases? Theory versus experiment". Science. 278 (5340): 1128–32. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1128A. doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1128. PMID 9353195.

- Agback P, Agback T (2018). "Direct evidence of a low barrier hydrogen bond in the catalytic triad of a Serine protease". Sci. Rep. 8 (1): 10078. Bibcode:2018NatSR...810078A. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28441-7. PMC 6031666. PMID 29973622.

- Schutz CN, Warshel A (2004). "The low barrier hydrogen bond (LBHB) proposal revisited: the case of the Asp... His pair in serine proteases". Proteins. 55 (3): 711–23. doi:10.1002/prot.20096. PMID 15103633. S2CID 34229297.

- Warshel A, Papazyan A (1996). "Energy considerations show that low-barrier hydrogen bonds do not offer a catalytic advantage over ordinary hydrogen bonds". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (24): 13665–70. Bibcode:1996PNAS...9313665W. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.24.13665. PMC 19385. PMID 8942991.

- Fersht, A.R.; Requena, Y (1971). "Mechanism of the Chymotrypsin-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Amides. pH Dependence of kc and Km.' Kinetic Detection of an Intermediate". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93 (25): 7079–87. doi:10.1021/ja00754a066. PMID 5133099.

- Zeeberg, B; Caswell, M; Caplow, M (1973). "Concerning a reported change in rate-determining step in chymotrypsin catalysis". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95 (8): 2734–5. doi:10.1021/ja00789a081. PMID 4694533.

- Shafee T (2014). Evolvability of a viral protease: experimental evolution of catalysis, robustness and specificity (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/CAM.16528.

- Ekici OD, Paetzel M, Dalbey RE (2008). "Unconventional serine proteases: variations on the catalytic Ser/His/Asp triad configuration". Protein Sci. 17 (12): 2023–37. doi:10.1110/ps.035436.108. PMC 2590910. PMID 18824507.

- McGrath ME, Wilke ME, Higaki JN, et al. (1989). "Crystal structures of two engineered thiol trypsins". Biochemistry. 28 (24): 9264–70. doi:10.1021/bi00450a005. PMID 2611228.

- Polgár L, Asbóth B (1986). "The basic difference in catalyses by serine and cysteine proteinases resides in charge stabilization in the transition state". J. Theor. Biol. 121 (3): 323–6. Bibcode:1986JThBi.121..323P. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80111-4. PMID 3540454.

- Brandt W, Wessjohann LA (2005). "The functional role of selenocysteine (Sec) in the catalysis mechanism of large thioredoxin reductases: proposition of a swapping catalytic triad including a Sec-His-Glu state". ChemBioChem. 6 (2): 386–94. doi:10.1002/cbic.200400276. PMID 15651042. S2CID 25575160.

- Damblon C, Raquet X, Lian LY, et al. (1996). "The catalytic mechanism of beta-lactamases: NMR titration of an active-site lysine residue of the TEM-1 enzyme". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (5): 1747–52. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1747D. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.5.1747. PMC 39852. PMID 8700829.

- Jelsch C, Lenfant F, Masson JM, et al. (1992). "Beta-lactamase TEM1 of E. coli. Crystal structure determination at 2.5 A resolution". FEBS Lett. 299 (2): 135–42. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(92)80232-6. PMID 1544485.

- Brannigan JA, Dodson G, Duggleby HJ, et al. (1995). "A protein catalytic framework with an N-terminal nucleophile is capable of self-activation". Nature. 378 (6555): 416–9. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..416B. doi:10.1038/378416a0. PMID 7477383. S2CID 4277904.

- Cheng H, Grishin NV (2005). "DOM-fold: a structure with crossing loops found in DmpA, ornithine acetyltransferase, and molybdenum cofactor-binding domain". Protein Sci. 14 (7): 1902–10. doi:10.1110/ps.051364905. PMC 2253344. PMID 15937278.

- Sun Y, Yin S, Feng Y, et al. (2014). "Molecular basis of the general base catalysis of an α/β-hydrolase catalytic triad". J. Biol. Chem. 289 (22): 15867–79. doi:10.1074/jbc.m113.535641. PMC 4140940. PMID 24737327.

- Rauwerdink A, Kazlauskas RJ (2015). "How the Same Core Catalytic Machinery Catalyzes 17 Different Reactions: the Serine-Histidine-Aspartate Catalytic Triad of α/β-Hydrolase Fold Enzymes". ACS Catal. 5 (10): 6153–6176. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5b01539. PMC 5455348. PMID 28580193.

- Beveridge AJ (1996). "A theoretical study of the active sites of papain and S195C rat trypsin: implications for the low reactivity of mutant serine proteinases". Protein Sci. 5 (7): 1355–65. doi:10.1002/pro.5560050714. PMC 2143470. PMID 8819168.

- Allen MD, Buchberger A, Bycroft M (2006). "The PUB domain functions as a p97 binding module in human peptide N-glycanase". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (35): 25502–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M601173200. PMID 16807242.

- Sanchez-Pulido L, Ponting CP (2016). "Vasohibins: new transglutaminase-like cysteine proteases possessing a non-canonical Cys-His-Ser catalytic triad". Bioinformatics. 32 (10): 1441–5. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv761. PMC 4866520. PMID 26794318.

- Sato Y, Sonoda H (2007). "The vasohibin family: a negative regulatory system of angiogenesis genetically programmed in endothelial cells". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1161/01.atv.0000252062.48280.61. PMID 17095714.

- Shin S, Yun YS, Koo HM, et al. (2003). "Characterization of a novel Ser-cisSer-Lys catalytic triad in comparison with the classical Ser-His-Asp triad". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (27): 24937–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302156200. PMID 12711609.

- Cerqueira NM, Moorthy H, Fernandes PA, et al. (2017). "The mechanism of the Ser-(cis)Ser-Lys catalytic triad of peptide amidases". Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19 (19): 12343–12354. Bibcode:2017PCCP...1912343C. doi:10.1039/C7CP00277G. PMID 28453015. Archived from the original on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- Toscano MD, Woycechowsky KJ, Hilvert D (2007). "Minimalist active-site redesign: teaching old enzymes new tricks". Angew. Chem. 46 (18): 3212–36. doi:10.1002/anie.200604205. PMID 17450624.

- Abrahmsén L, Tom J, Burnier J, et al. (1991). "Engineering subtilisin and its substrates for efficient ligation of peptide bonds in aqueous solution". Biochemistry. 30 (17): 4151–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.9606. doi:10.1021/bi00231a007. PMID 2021606.

- Jackson DY, Burnier J, Quan C, et al. (1994). "A designed peptide ligase for total synthesis of ribonuclease A with unnatural catalytic residues". Science. 266 (5183): 243–7. Bibcode:1994Sci...266..243J. doi:10.1126/science.7939659. JSTOR 2884761. PMID 7939659.

- Syed R, Wu ZP, Hogle JM, et al. (1993). "Crystal structure of selenosubtilisin at 2.0-A resolution". Biochemistry. 32 (24): 6157–64. doi:10.1021/bi00075a007. PMID 8512925.

- Mao S, Dong Z, Liu J, et al. (2005). "Semisynthetic tellurosubtilisin with glutathione peroxidase activity". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (33): 11588–9. doi:10.1021/ja052451v. PMID 16104720.

- Devillanova FA, Du Mont W (2013). Handbook of Chalcogen Chemistry. Vol. 1: new perspectives in sulfur, selenium and tellurium (2nd ed.). Cambridge: RSC. ISBN 9781849736237. OCLC 868953797.

- Bouroushian M (2010). "Electrochemistry of the Chalcogens". Electrochemistry of Metal Chalcogenides. Monographs in Electrochemistry. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 57–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-03967-6_2. ISBN 9783642039669.

- Shafee T, Gatti-Lafranconi P, Minter R, et al. (2015). "Handicap-Recover Evolution Leads to a Chemically Versatile, Nucleophile-Permissive Protease". ChemBioChem. 16 (13): 1866–9. doi:10.1002/cbic.201500295. PMC 4576821. PMID 26097079.

- Okochi N, Kato-Murai M, Kadonosono T, et al. (2007). "Design of a serine protease-like catalytic triad on an antibody light chain displayed on the yeast cell surface". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 77 (3): 597–603. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1197-0. PMID 17899065. S2CID 35590920.

- Rajagopalan S, Wang C, Yu K, et al. (2014). "Design of activated serine-containing catalytic triads with atomic-level accuracy". Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 (5): 386–91. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1498. PMC 4048123. PMID 24705591.

- Bhowmick D, Mugesh G (2015). "Introduction of a catalytic triad increases the glutathione peroxidase-like activity of diaryl diselenides". Org. Biomol. Chem. 13 (34): 9072–82. doi:10.1039/C5OB01294E. PMID 26220806.

- Bhowmick D, Mugesh G (2015). "Insights into the catalytic mechanism of synthetic glutathione peroxidase mimetics". Org. Biomol. Chem. 13 (41): 10262–72. doi:10.1039/c5ob01665g. PMID 26372527.

- Nothling MD, Ganesan A, Condic-Jurkic K, et al. (2017). "Simple Design of an Enzyme-Inspired Supported Catalyst Based on a Catalytic Triad". Chem. 2 (5): 732–745. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2017.04.004.

- Gulseren G, Khalily MA, Tekinay AB, et al. (2016). "Catalytic supramolecular self-assembled peptide nanostructures for ester hydrolysis". J. Mater. Chem. B. 4 (26): 4605–4611. doi:10.1039/c6tb00795c. hdl:11693/36666. PMID 32263403.

- Halabi N, Rivoire O, Leibler S, et al. (2009). "Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure". Cell. 138 (4): 774–86. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.038. PMC 3210731. PMID 19703402.

- Murzin AG (1998). "How far divergent evolution goes in proteins". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 8 (3): 380–387. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(98)80073-0. PMID 9666335.

- Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC (2001). "Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70 (1): 209–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. PMID 11395407.

- Murphy JM, Farhan H, Eyers PA (2017). "Bio-Zombie: the rise of pseudoenzymes in biology". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 45 (2): 537–544. doi:10.1042/bst20160400. PMID 28408493.

- Stehle F, Brandt W, Stubbs MT, et al. (2009). "Sinapoyltransferases in the light of molecular evolution". Phytochemistry. Evolution of Metabolic Diversity. 70 (15–16): 1652–62. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.023. PMID 19695650.

- Dimitriou PS, Denesyuk A, Takahashi S, et al. (2017). "Alpha/beta-hydrolases: A unique structural motif coordinates catalytic acid residue in 40 protein fold families". Proteins. 85 (10): 1845–1855. doi:10.1002/prot.25338. PMID 28643343. S2CID 25363240.

- Smith JL (1998). "Glutamine PRPP amidotransferase: snapshots of an enzyme in action". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 8 (6): 686–94. doi:10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80087-0. PMID 9914248.

- Smith JL, Zaluzec EJ, Wery JP, et al. (1994). "Structure of the allosteric regulatory enzyme of purine biosynthesis". Science. 264 (5164): 1427–33. Bibcode:1994Sci...264.1427S. doi:10.1126/science.8197456. PMID 8197456.

- "Clans of Mixed (C, S, T) Catalytic Type". www.ebi.ac.uk. MEROPS. Retrieved 20 Dec 2018.

- Fischer K, Reynolds SL (2015). "Pseudoproteases: mechanisms and function". Biochem. J. 468 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1042/BJ20141506. PMID 25940733.

- Todd AE, Orengo CA, Thornton JM (2002). "Sequence and structural differences between enzyme and nonenzyme homologs". Structure. 10 (10): 1435–51. doi:10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00861-4. PMID 12377129.

- Iversen LF, Kastrup JS, Bjørn SE, et al. (1997). "Structure of HBP, a multifunctional protein with a serine proteinase fold". Nat. Struct. Biol. 4 (4): 265–8. doi:10.1038/nsb0497-265. PMID 9095193. S2CID 19949043.

- Zettl M, Adrain C, Strisovsky K, et al. (2011). "Rhomboid family pseudoproteases use the ER quality control machinery to regulate intercellular signaling". Cell. 145 (1): 79–91. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.047. PMC 3149277. PMID 21439629.

- Lemberg MK, Adrain C (2016). "Inactive rhomboid proteins: New mechanisms with implications in health and disease". Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 60: 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.06.022. hdl:10400.7/759. PMID 27378062.

- Cheng CY, Morris I, Bardin CW (1993). "Testins Are Structurally Related to the Mouse Cysteine Proteinase Precursor But Devoid of Any Protease/Anti-Protease Activity". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 191 (1): 224–231. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.1206. PMID 8447824.

- Pelc LA, Chen Z, Gohara DW, et al. (2015). "Why Ser and not Thr brokers catalysis in the trypsin fold". Biochemistry. 54 (7): 1457–64. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00014. PMC 4342846. PMID 25664608.