Catherine Filene Shouse

Catherine Filene Shouse (June 9, 1896 – December 14, 1994) was an American researcher and philanthropist. She graduated in 1918 from Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts.[1] She worked for the Women's Division of the U.S. Employment Service of the Department of Labor, and was the first woman appointed to the Democratic National Committee in 1925. She was also the editor of the Woman's National Democratic Committee's Bulletin (1929–32), and the first woman to chair the Federal Prison for Women Board.

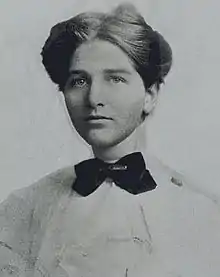

Catherine Filene Shouse | |

|---|---|

Catherine Filene Shouse, c. 1913 | |

| Born | Catherine Filene June 9, 1896 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | December 14, 1994 (aged 98) Naples, Florida, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Wheaton College Radcliffe College Harvard Graduate School of Education |

| Occupation(s) | Editor, researcher, philanthropist |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977) National Medal of Arts (1994) |

Finally, she was a strong supporter of the arts and served as chair of the President's Music Committee's Person-to-Person Program (1957–1963). In 1966 she donated her personal property, Wolf Trap Farm, to the National Park Service. This farm would go on to become Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, where Shouse would serve as founder until her death in 1994.

1917–1963: activist and organizer

Catherine Filene was born on June 9, 1896, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Abraham Lincoln Filene and the former Thérèse Weill. Born into a wealthy merchandising family, her grandfather William Filene founded Filene's department store, and her mother started the Boston Music School for Underprivileged Children.[2]

When Shouse was an undergraduate student at Wheaton College, she convened a lecture series. It was the first Intercollegiate Vocational Conference for Women. The focus of the conference was to make jobs more accessible to women. The lecture series was held at Wheaton College and it initiated annual vocational conferences at Wheaton College until the 1950s. Shouse then proceeded to found Wheaton's first Vocational Bureau, which assisted alumnae in locating employment.[3] In 1917, Shouse was able to utilize experience acquired through her undergraduate and her prior activist activities. She was employed by the Women's Division of the United States Employment Service of the Department of Labor. Shouse was hired as the assistant to the chief. Three years later (1920), she published her original work, Careers for Women,[4] which Shouse revised in 1934. Her personally signed first copy is housed in Hood College's Catherine Filene Shouse Career Center.[5] Hood College named their career center after Shouse after her substantial contribution which enabled the college to obtain most of their modern technological equipment for worldwide career information.

President Calvin Coolidge appointed Shouse chair of the Federal Prison for Women in 1926. She was the first woman to occupy this position and immediately began to transform the system. Shouse established job training and rehabilitation programs. Three years later (1929), Shouse created the Institute of Women's Professional Relations. This organization hosted national conferences that highlighted opportunities for women with education beyond high school. In 1925, Shouse was the first woman to be appointed to the Democratic National Committee. Four years later, she served as editor of the Women's National Democratic Committee's Bulletin from 1929 to 1932.

Shouse was a prolific supporter of the arts. She was a volunteer fundraiser for the National Symphony Orchestra. Candlelight Concerts in Washington, D.C., were organized and sponsored by Shouse from 1935 to 1942 in order to supplement the National Symphony Orchestra's salaries. She was the first to do such. From 1957 to 1963, Shouse served as chair of the President's Music Committee's Person-to-Person Program. During her tenure, the program produced annual national and international performances. Under Shouse's direction, the President's Music Committee's Person-to-Person Program organized the first International Jazz Festival in 1962, which was one year after Shouse donated forty acres of her farm at Wolf Trap to the American Symphony Orchestra (1961).[6]

Board service

1935 Member, board of directors, Community Chest, Washington.

1947 Trustee, Filene Foundation (Boston)

1949 Elected to Board of National Symphony Orchestra Association; vice president, 1951–68; honorary vice president, 1968

1952–63 Board, National Arbitration Association.

1955 Board, Lincoln Filene Center of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Tufts University.

1965–72 Board, Opera Society of Washington.

1968 Board, Wolf Trap Foundation. Chairman, Executive Committee, 1975.

1975 Appointed to Board of Overseers, Hopkins Center, Dartmouth College; chair, 1981.

1984 Advisory Board, Washington Conservatory.

1991 Served on Board of Directors of Yale University School of Music.

1930–1966: Wolf Trap Farm

Shouse's desire for her children to develop an appreciation for and a relationship with nature resulted in the establishment of America's first and only national park for the performing arts – Wolf Trap. Shouse believed children should have the opportunity to learn about nature and animals and she wanted her children to be closer to nature than would be possible living in her urbanized Georgetown residence.

Consequently, she set out to look for a farm. Shouse – who was short on money but long on conviction – got into her car in 1930, with a friend visiting from Boston, and drove out of Georgetown into Virginia. Shouse encountered large tracts of farmland in Vienna, Virginia. She asked a man who was standing in the road if any of the land was for sale. The man replied, "Nothing for sale. Everybody keeps his land because the division was made after the American Civil War, 52 acre properties, and because of them we don't want any strangers coming in."[8]: 1 Undeterred, Shouse continued to look for properties. That evening, however, while reading through the classified ads in the newspaper, she came across a property for sale advertisement. It was the exact farm she inquired about earlier that day. In February 1930, Shouse bought The Wolf Trap Farm for $5,300.00.

Initially, Shouse grew oats, wheat, alfalfa and other farm items for family and friends. However, at the advent of and during World War II, Shouse's Wolf Trap Farm fed many more. Fresh produce (and food in general) was scarce during the war years and scores of people were allowed to take advantage of Wolf Trap.

Wolf Trap also frequently hosted notable foreign and domestic political figures. In a 1994 interview, Shouse recalls, "I remember the night…that Lord Halifax, the British Ambassador, called and told me, 'I'll bring Dumbarton Oaks British representatives to dinner tomorrow night with you. They haven't seen a whole ham, a whole chicken, or much food of any kind since the beginning of the war.' They came on an August evening….and the Lord Halifax watched their eating and drinking because the next morning was the Dumbarton Oaks meeting of the many countries, and you know the Dumbarton was the predecessor of the United Nations."[8]: 2

During World War II, Wolf Trap became a haven for many American soldiers on leave. According to Shouse, "During the war it became an oasis for many of the people on leave. And General [Omar] Bradley came back from the big horrible battle and that horrible experience that our people had in Luxembourg. He was here. General [George C.] Marshall came out ... Wolf Trap meant a great deal, not only to the people here, but to people that were abroad."[8]: 3

When Shouse bought Wolf Trap, it came with a dilapidated farmhouse on the property. Shouse used the last of her savings to buy the initial plot of land. Thus, Shouse along with family and friends physically renovated the house (and property) themselves, using whatever resources they could get their hands on. She also added to the initial property. Whenever she obtained extra money, Shouse would buy adjacent plots of land to add to Wolf Trap. Before long, Wolf Trap was 168 acres.

While Shouse was alive, Wolf Trap was enjoyed by countless people from many nations and from myriad backgrounds. Shouse often brought disabled and disadvantaged children from Washington, D.C., to Wolf Trap to give them hayrides. Multitudes of people would come to Wolf Trap to enjoy a walk through the woods, picking laurel, etc. Shouse wanted people to be able to enjoy Wolf Trap even when she was no longer here.

To ensure that her dream would become a reality, Shouse approached the Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall and asked, "You have many parks for recreation, but you have nothing in the performing arts. And people find through performing arts their balance in tense times, their joys in their everyday life. Do you want Wolf Trap?"[8]: 3 That initial conversation with the Secretary of the Interior led to Shouse donating Wolf Trap to the federal government. The United States government officially accepted Wolf Trap in 1966 and designated it as a national park for the performing arts under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service – the first of its kind.

1971–1994: Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts

As the founder of Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Shouse helped lead its development into one of the most prominent performing arts venues in the Washington D.C. area from the beginning. During the construction of the Filene Center—named after Shouse's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln Filene[9]—in 1971, Shouse even visited and assisted workers on site, even offering sandwiches and other refreshments when possible.[10] Shouse also helped design the Filene Center, working closely with renowned architects John H. MacFadyen and Edward F. Knowles to create a state-of-the-art venue that would still be able to "retain the unspoiled atmosphere of the setting.[11]

In Wolf Trap's early years, Shouse also frequently traveled the world to scout talent and performers, including persuading the Chinese government to allow the Performing Arts Company of the People's Republic to perform at Wolf Trap in 1978.[12]

In 1982, at age 85, Shouse led a rigorous effort to rebuild the Filene Center, Wolf Trap's main performing arts venue, after it was destroyed by a fire that April. In addition to helping convince the federal government to donate $9 million to the project, Shouse helped to raise an additional $15 million from other sources for the effort. While the new Filene Center would be completed and re-opened in 1984, Shouse also helped salvage the 1982 and 1983 seasons by leading the construction of the Meadow Center, an enormous tent where performances would take place during these two years.[13]

In 1991, Shouse was reportedly close to breaking ties with Wolf Trap over a dispute relating to the park's 20th anniversary. In honor of the anniversary, Shouse planned to put on a television special to celebrate the occasion, a plan shut down by the Wolf Trap Foundation's executive committee due to budget constraints (although the special would be resurrected later that year).[14] Nevertheless, Shouse didn't resign and would stay with Wolf Trap until her death three years later.

On December 14, 1994, Shouse died of heart failure at her winter home in Naples, Florida on at the age of 98.

1956–1975: presidential appointments

Not only were Shouse's talents and abilities acknowledged and appreciated by local communities and organizations, her gifts were honored and utilized by many United States presidents. In addition to her appointment by President Calvin Coolidge to chair the first Federal Prison for Women, at the request of President Herbert Hoover, Shouse organized the Washington Hungarian Relief Fund and raised a half-million dollars in less than a month (1956).[15] Shouse was appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to chair the President's Music Committee from 1957 to 1963.

President Eisenhower also appointed Shouse to the first board of trustees of the National Cultural Center (1958). President Kennedy reappointed Shouse to that position in 1962. In 1964, the National Cultural Center was renamed The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts following the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy. President Richard Nixon appointed Shouse to the board of trustees of the renamed Kennedy Center for a ten-year term in 1970.[15] During that time, Shouse also served on the Executive and Building Committees of the Kennedy Center. Shouse was appointed to the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Commission in 1973 by President Nixon. She was appointed to the official commissions on women's rights by Presidents Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and John Kennedy. Last but not least, in 1975 President Gerald Ford appointed Shouse to the Commission on Presidential Scholars.

In addition to her presidential appointments, Shouse was appointed to the first Virginia Commission of the Arts and Humanities in 1968, by Governor Mills E. Godwin Jr. In 1971, Shouse was reappointed to that position by Governor Linwood Holton.

Education

1918 B.A., Wheaton College, Norton, Massachusetts

1923 M.Ed., Harvard University Graduate School of Education

Honorary degrees

1963 Doctor of Humanities, Tufts University

1964 Doctor of Humanities, Wheaton College

1971 Doctor of Laws, American University

1975 Doctor of Humanities, George Washington University

1975 Doctor of Humanities, Bucknell University

1975 Doctor of Music, The New England Conservatory of Music

1977 Doctor of Humanities, Catholic University

1977 Doctor of Humanities, College of William and Mary

1979 Doctor of Humane Letters, University of Maryland

1981 Doctor of Humanities, Hood College

1983 Doctor of Letters, Gonzaga University

1984 Doctor of Music, Shenandoah College & Conservatory of Music

1986 Doctor of Humane Letters, Marymount University

Decorations, citations, and honors

In 1977, Shouse was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford, and was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. In 2007, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Shouse received myriad other awards, including the Living Legacy Award from the Women's International Center, the Vienna (Austria) Medal of Honor for Assistance to Austrian Youth, and the City of Paris Award (both in 1949). She was the first woman to receive the German Federal Republic's Commander's Cross of Merit (1954), and Shouse was named by Queen Elizabeth II, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1976).

In 1971, Shouse was named Honorary Park Superintendent by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. She also received the Humanitarian Award from the National Recreation and Park Association in 1972 and the Conservation Service Award from the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1973.

Filene firsts

- 1917 Organized the first Intercollegiate Vocational Conference for Women.

- 1919 First woman appointed to the National Democratic Committee representing Massachusetts. Also, State Democratic Committee.

- 1923 First woman to receive a degree from Harvard University (M.Ed.).

- 1926 First woman appointed by President Calvin Coolidge as chairman of the Federal Prison for Women. She instituted a job training and rehabilitation program.

- 1954 First woman to receive the German Federal Republic's Commander's Cross of Merit.

- 1968 Appointed by Governor Godwin to the first Virginia Commission of the Arts and Humanities.

- 1972 First woman to hold a Gold Card in the Stage Employees Union #22 of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Motion Picture Operators of the U.S.A. and Canada.

- 1975 First woman to receive the Abraham Lincoln Award from the American Hungarian Foundation.

- 1975 First person outside of the federal government to receive the Recording Industry Association of America Annual Award.

- 1979 First recipient of the first Governor's Award for the Arts in Virginia.

- 1985 First Honorary Member of the Washington College Friends of the Arts Committee.

- 2012 To date, Shouse is the first and only person to receive both an American Medal of Freedom and a British Award of Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Publications

- Careers for women. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1920.

References

- "Shouse, Catherine Filene. Papers, 1878–1998: A Finding Aid". Oasis.lib.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- Hume, Paul. "The Woman Who Built Wolf Trap." The Washington Post 1 July 1971: C1. Print.

- "Catherine Filene Shouse – College History | Wheaton College". Archived from the original on 2012-08-04. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

- Harvard Library. www.hollis.harvard.edu.

- "Hood College | Why are we Named After Catherine Filene Shouse?". Archived from the original on 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Harvard University Library Open Collection Program. ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/shouse.html.

- Catherine Filene Shouse Papers, 1878–1998. http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~sch00014 Archived 2014-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- 1994 Interview, Catherine Filene Shouse. Wolf Trap Archives, Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts.

- Carr, Eve and Millard. The Wolf Trap Story. Vienna, VA: The Wolf Trap Associates, 1977. Print. p. 14.

- Zegas, Judy B. Wolf Trap--Celebrating the Past, Looking to the Future. Vienna, VA: Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts, 1991. Print.

- Millard, The Wolf Trap Story, p. 16.

- Levy, Claudia. "Wolf Trap Founder Dies at Age 98." The Washington Post, December 14, 1994. Print.

- McLellan, Joseph. "The Many Gifts of Kay Shouse." The Washington Post, December 14, 1994. Print.

- Masters, Kim. "Wolf Trap Founder May Break with Center." The Washington Post, February 22, 1991: B1+. Print.

- Wolf Trap Archives, Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Vienna, VA.