Cherokee freedmen controversy

The Cherokee Freedmen controversy was a political and tribal dispute between the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen regarding the issue of tribal membership. The controversy had resulted in several legal proceedings between the two parties from the late 20th century to August 2017.

During the antebellum period, the Cherokee and other Southeast Native American nations known as the Five Civilized Tribes held African-American slaves as workers and property. The Cherokee "elites created an economy and culture that highly valued and regulated slavery and the rights of slave owners" and, in "1860, about thirty years after their removal to Indian Territory from their respective homes in the Southeast, Cherokee Nation members owned 2,511 slaves." It was slave labor that "allowed wealthy Indians to rebuild the infrastructure of their lives even bigger and better than before," such as John Ross, a Cherokee chief, who "lived in a log cabin directly after Removal" but a few years after, "he replaced this dwelling with a yellow mansion, complete with a columned porch."[1] After the American Civil War, the Cherokee Freedmen were emancipated and allowed to become citizens of the Cherokee Nation in accordance with a reconstruction treaty made with the United States in 1866. In the early 1880s, the Cherokee Nation administration amended citizenship rules to require direct descent from an ancestor listed on the "Cherokee By Blood" section of the Dawes Rolls. The change stripped descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen of citizenship and voting rights unless they satisfied this new criterion.

On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Supreme Court ruled that the membership change was unconstitutional and that the Freedmen descendants were entitled to enroll in the Cherokee Nation. A special election, held on March 3, 2007, resulted in passage of a constitutional amendment that excluded the Cherokee Freedmen descendants from membership unless they satisfied the "Cherokee by blood" requirement.[2] The Cherokee Nation District Court voided the 2007 amendment on January 14, 2011. This decision was overturned by a 4–1 ruling in Cherokee Nation Supreme Court on August 22, 2011.

The ruling also excluded the Cherokee Freedmen descendants from voting in the special run-off election for Principal Chief. In response, the Department of Housing and Urban Development froze $33 million in funds and the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs wrote a letter objecting to the ruling. Afterward, the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen descendants, and the U.S. government reached an agreement in federal court to allow the Freedmen descendants to vote in the special election.

Through several legal proceedings in United States and Cherokee Nation courts, the Freedmen descendants conducted litigation to regain their treaty rights and recognition as Cherokee Nation members.[3] While the Cherokee Nation filed a complaint in federal court in early 2012, Freedmen descendants and the United States Department of the Interior filed separate counterclaims on July 2, 2012.[4][5] The U.S. Court of Appeals upheld tribal sovereignty, but stated that the cases had to be combined due to the same parties being involved. On May 5, 2014, in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, oral arguments were made in the first hearing on the merits of the case. On August 30, 2017, the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants and the U.S. Department of the Interior, granting the Freedmen descendants full rights to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation has accepted this decision, effectively ending the dispute. However, the Nation is still grappling with the effects. In 2021, the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court ruled to remove the words "by blood" from its constitution and other legal doctrines. The words had been "added to the constitution in 2007" and had "been used to exclude Black people whose ancestors were enslaved by the tribe from obtaining full Cherokee Nation citizenship rights."[6]

Cherokee Freedmen

Freedmen is one of the terms given to emancipated slaves and their descendants after slavery was abolished in the United States following the American Civil War. In this context, "Cherokee Freedmen" refers to the African-American men and women who were formerly slaves of the Cherokee before and after removal to Indian Territory and the American Civil War. It includes the descendants of such former slaves, as well as those born in unions between formerly enslaved or enslaved African Americans and Cherokee tribal members.

After their emancipation and subsequent citizenship, the Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants struggled to be accepted as a legitimate part of the Cherokee Nation.[7] Some Freedmen have been active in the tribe, voted in elections, ran businesses, attended Cherokee stomp dances, knew Cherokee traditions, folklore, and the Cherokee language. There were Cherokee Freedmen who served on the tribal council, holding district seats in Tahlequah, Illinois, and Cooweescoowee. Joseph Brown was elected as the first Cherokee Freedman councilman in 1875, followed by Frank Vann in 1887, Jerry Alberty in 1889, Joseph "Stick" Ross in 1893, and the election of Ned Irons and Samuel Stidham in 1895. The most known of the councilmen was Joseph "Stick" Ross, who was born into slavery and owned by Principal Chief John Ross before his family's emancipation. Stick Ross became a civic leader with several companies and landmarks named after him, including Stick Ross Mountain in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.[8][9] Leslie Ross, Stick's great-grandson, says,

He knew sign language and spoke Cherokee and Seminole. He was a trapper and a farmer and a rancher. And he was sheriff at one time, too. He was pretty renowned in Tahlequah.[10]

The civic position for Freedmen increased by the time of the Dawes Commission, which convinced the Cherokee and the other Five Civilized Tribes to break up tribal land in Indian Territory into individual allotments for households. The Cherokee Freedmen were among the three groups listed on the Dawes Rolls, records created by the Dawes Commission to list citizens in Indian Territory. With the abolition of tribal government by the Curtis Act of 1898, the Freedmen as well as other Cherokee citizens were counted as US citizens and Oklahoma was granted statehood in 1907. After the Cherokee Nation reorganized and re-established its government via passage of the Principal Chiefs Act in 1970, the Freedmen participated in the 1971 tribal elections held for the office of principal chief. The election was the first held by the Cherokee since the passage of the Curtis Act.[11]

Several Cherokee Freedmen descendants have continued to embrace this historical connection. Others, after having been excluded from the tribe for two decades in the late twentieth century and subject to a continuing citizenship struggle, have become ambivalent about their ties. They no longer think identifying as Cherokee is necessary to their personal identity.[12]

History

Slavery among the Cherokee

Slavery was a component of Cherokee society prior to European colonization, as they frequently enslaved enemy captives taken during times of conflict with other indigenous tribes.[13] By their oral tradition, the Cherokee viewed slavery as the result of an individual's failure in warfare and as a temporary status, pending release or the slave's adoption into the tribe.[14] During the colonial era, Carolinian settlers purchased or impressed Cherokees as slaves during the late 17th and early 18th century.[15]

From the late 1700s to the 1860s, the Five Civilized Tribes in the American Southeast began to adopt certain Euro-American customs. Some men acquired separate land and became planters, purchasing enslaved African Americans for laborers in field work, domestic service, and various trades.[16] The 1809 census taken by Cherokee agent Colonel Return J. Meigs Sr. counted 583 "Negro slaves" held by Cherokee slaveowners.[17] By 1835, that number increased to 1,592 slaves, with more than seven percent (7.4%) of Cherokee families owning slaves. This was a higher percentage than generally across the South, where about 5% of families owned slaves.[18]

Cherokee slaveowners took their slaves with them on the Trail of Tears, the forced removal of Native Americans from their original lands to Indian Territory by the federal government. Of the Five Civilized Tribes removed to Indian Territory, the Cherokee were the largest tribe and held the most enslaved African Americans.[19] Prominent Cherokee slaveowners included the families of Joseph Lynch, Joseph Vann, Major Ridge, Stand Watie, Elias Boudinot, and Principal Chief John Ross.

While slavery was less common among full-blood Cherokee, because these people tended to live in more isolated settlements away from European-American influence and trade, both full-blood and mixed-blood Cherokee became slaveowners.[20] Among the notable examples of the former is Tarsekayahke, also known by the name "Shoe Boots". He participated in the 1793 raid on Morgan's Station, Montgomery County, Kentucky, the last Indian raid in the state. The raiders took as captive Clarinda Allington, a white adolescent girl, and she was adopted into a Cherokee family and assimilated. Shoe Boots later married her and they had children: William, Sarah and John.[21] Shoe Boots fought for the Cherokee in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend during the Creek War.

At this time Shoe Boots held two African-American slaves, including Doll, who was about Clarinda's age.[21] Clarinda left, taking their children with her. Afterward, Shoe Boots took Doll as a sexual partner or concubine. He fathered three children with her, whom he named as Elizabeth, Polly and John.[22] The couple essentially had a common-law marriage.

The Cherokee tribe had a matrilineal kinship system, by which inheritance and descent were passed on the mother's side; children were considered born into her family and clan. Since these mixed-race children were born to a slave, they inherited Doll's slave status. The Cherokee had adopted this element of slave law common among the slave states in the United States, known as partus sequitur ventrem. For the children to be fully accepted in the tribe, they would ordinarily have had to be adopted by a Cherokee woman and her clan. But on October 20, 1824, Shoe Boots petitioned the Cherokee National Council to grant emancipation for his three children and have them recognized as free Cherokee citizens. Shoe Boots stated in his petition,

These is the only children I have as Citizens of this Nation, and as the time I may be called to die is uncertain, My desire is to have them as free citizens of this nation. Knowing what property I may have, is to be divided amongst the Best of my friends, how can I think of them having bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh to be called their property, and this by my imprudent conduct, and for them and their offspring to suffer for generations yet unborn, is a thought too great a magnitude for me to remain silent any longer.

After consideration, his request was granted by the Cherokee National Council on November 6, 1824. That year the Council passed a law prohibiting marriage between Cherokee and slaves, or Cherokee and free blacks. But, the following year in 1825, the Council passed a law giving automatic Cherokee citizenship to mixed-race children born to white women and their Cherokee husbands. Gradually more Cherokee men were marrying white women from outside the tribe. The Council wanted to provide a way for the children of these male leaders to be considered members of the tribe.[23] Before this time, mixed-race children had generally been born to Cherokee women and white men, most often traders. Because of the matrilineal kinship system, these children were traditionally considered born to the mother's family and clan, and thus members of the tribe by birth.

While granting his request for emancipation of his children, the Council ordered Shoe Boots to cease his relationship with Doll. But he fathered two more boys with her, twin sons Lewis and William, before his death in 1829. Heirs of his estate later forced these two sons into slavery. His sisters inherited his twin sons as property, and they unsuccessfully petitioned the council to grant emancipation and citizenship to the twins.[24][25]

The nature of enslavement in Cherokee society in the antebellum years was often similar to that in European-American slave society, with little difference between the two.[26] The Cherokee instituted their own slave code and laws that discriminated against slaves and free blacks.[27] Cherokee law barred intermarriage of Cherokee and blacks, whether the latter were enslaved or free. African Americans who aided slaves were to be punished with 100 lashes on the back. Cherokee society barred those of African descent from holding public office, bearing arms, voting, and owning property. It was illegal for anyone within the limits of the Cherokee Nation to teach blacks to read or write. This law was amended so that the punishment for non-Cherokee citizens teaching blacks was a request for removal from the Cherokee Nation by authorities.[28][29]

After removal to Indian Territory with the Cherokee, enslaved African Americans initiated several revolts and escape attempts, attesting to their desire for freedom. In the Cherokee Slave Revolt of 1842, several African-American slaves in Indian Territory, including 25 held by Cherokee planter Joseph Vann, left their respective plantations near Webbers Falls, Oklahoma to escape to Mexico. The slaves were captured by a Cherokee militia under the command of Captain John Drew of the Cherokee Lighthorse near Fort Gibson. On December 2, 1842, the Cherokee National Council passed "An Act in regard to Free Negroes"; it banned all free blacks from the limits of the Cherokee Nation by January 1843, except those freed by Cherokee slaveowners. In 1846, an estimated 130–150 African slaves escaped from several plantations in Cherokee territory. Most of the slaves were captured in Seminole territory by a joint group of Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole slaveowners.[30]

Civil War and abolition of slavery

By 1861, the Cherokee held about 4,000 black slaves. During the American Civil War, the Cherokee Nation was divided between support for the Union and support for the Confederate States of America. Principal Chief John Ross originally adopted a policy of neutrality in regard to the Civil War and relations with the two opposing forces. In July 1861, Ross and Creek chief Opothleyahola attempted to unite the Five Civilized Tribes in an agreement to remain neutral, but failed at establishing an inter-tribal alliance.[14]

Ross and the Cherokee council later agreed to side with the Confederacy on August 12, 1861. On October 7, 1861, Ross signed a treaty with General Albert Pike of the Confederacy and the Cherokee officially joined the other nations of the Five Civilized Tribes in establishing a Pro-Confederate alliance. After Ross's capture by Union forces on July 15, 1862, and his parole, he sided with the Union and repudiated the Confederate treaty. He remained in Union territory until the end of the war.[14]

Stand Watie, a longtime rival of Ross and a leader of the majority Pro-Confederate Cherokee, became Principal Chief of the Southern Cherokee on August 21, 1862. A wealthy planter and slaveholder, Watie served as an officer in the Confederate Army and was the last Brigadier General to surrender to the Union.

Cherokee loyal to Ross pledged support to the Union and acknowledged Ross as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Pro-Confederate Cherokee sided with Watie and the Southern Cherokee faction. Following the US Emancipation Proclamation, the Cherokee National Council, consisting of Pro-Union Cherokee and headed by acting Principal Chief Thomas Pegg, passed two emancipation acts that freed all enslaved African Americans within the limits of the Cherokee Nation.

The first, "An Act Providing for the Abolition of Slavery in the Cherokee Nation", was passed on February 18, 1863.[31]

Be it enacted by the Natl Council, That in view of the difficulties and evils which have arisen from the Institution of Slavery and which seem inseparable from its existence in the Cherokee Nation, The Delegation appointed to proceed to Washington are impowered and instructed to assure the President of the U States of the desire of the Authorities and People to remove that Institution from the statutes and Soil of the Cherokee Nation and of their wish to provide for that object at once upon the Principle of Compensation to the owners of Slaves not disloyal to the Government of the United States as tendered by Congress to States which shall abolish Slavery to their midst.

The second, "An Act Emancipating the Slaves in the Cherokee Nation", was passed on February 20, 1863.[32][33]

Be it enacted by the National Council: That all negro and other slaves within the lands of the Cherokee Nation be and they are hereby emancipated from slavery, and any person or persons who may have been held in slavery hereby declared to be forever free.

The acts became effective on June 25, 1863, and any Cherokee citizen who held slaves was to be fined no less than one thousand dollars or more than five thousand dollars. Officials who failed to enforce the act were to be removed and deemed ineligible to hold any office in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee became the sole nation of the Five Civilized Tribes to abolish slavery during the war. But despite the actions of the National Council, few slaves were freed. Those Cherokee loyal to the Confederacy held more slaves than did pro-Union Cherokee.[34] Despite agreeing to end slavery, pro-Union Cherokee did not provide for civil and social equality for Freedmen in the Cherokee Nation.[35]

Fort Smith Conference and Treaty of 1866

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the factions of Cherokee who supported the Union and those who supported the Confederacy continued to be at odds. In September 1865, each side was represented along with delegations from the other Five Civilized Nations and other nations to negotiate with the Southern Treaty Commission at Fort Smith, Arkansas. US Commissioner of Indian Affairs Dennis N. Cooley headed the Southern Treaty Commission, which included Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Superintendency Elijah Sells, Chief Clerk of the Bureau of Indian Affairs Charles Eli Mix, Brigadier General William S. Harney, Colonel Ely Samuel Parker, and Quaker philanthropist Thomas Wistar.

The Southern Cherokee delegates were Stand Watie, Elias Cornelius Boudinot, Richard Fields, James Madison Bell, and William Penn Adair. The Northern Cherokee led by John Ross were represented by Thomas Pegg, Lewis Downing, H. D. Reese, Smith Christie, and White Catcher. The US officials ignored the factional divisions and addressed the Cherokee as one entity, stating that their rights, annuities, and land claims from past treaties were voided due to the Cherokee joining the Confederacy.

On the September 9th meeting, Cooley insisted on several conditions for a treaty agreement that the Cherokee must comply with. Some of the conditions included the abolishment of slavery, full citizenship for the Cherokee Freedmen, and rights to annuities and land. The Southern Cherokee delegation hoped to achieve independent status for a Southern Cherokee Nation and wanted the U.S. government to pay for the relocation of Freedmen out of the Cherokee Nation to United States territory. The Pro-Union Cherokee delegation, whose government abolished slavery before the Civil War ended, were willing to adopt Freedmen into the tribe as members and to allocate land for their use.[36]

The two factions prolonged negotiations for a period of time with additional meetings held in Washington, DC between the two and the U.S. government. While negotiations took place, the US Department of the Interior tasked the newly established Freedmen's Bureau, headed by Brevet Major General John Sanborn, to observe the treatment of Freedmen in Indian Territory and regulate relations as a free labor system was established.[37]

The two Cherokee factions offered a series of treaty drafts to the U.S. government with Cooley giving each side twelve stipulations for the treaties. The Pro-Union Cherokee rejected four of those stipulations while agreeing with the rest. While the Southern Cherokee treaty had some support, the treaty offered by Ross' faction was ultimately selected. The Pro-Union faction was the sole Cherokee group that the U.S. government settled treaty terms with. Issues such as the status of Cherokee Freedmen and the voiding of the Confederate treaty were previously agreed upon, and both sides compromised on issues such as amnesty for Cherokee who had fought for the Confederacy.

On July 19, 1866, six delegates representing the Cherokee Nation signed a Reconstruction treaty with the United States in Washington, D.C. The treaty granted Cherokee citizenship to the Freedmen and their descendants (article 9). The treaty also set aside a large tract of land for Freedmen to settle, with 160 acres for each head of household (article 4), and granted them voting rights and self-determination within the constraints of the greater Cherokee Nation (article 5 and article 10).

The Cherokee Nation having, voluntarily, in February, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, by an act of the national council, forever abolished slavery, hereby covenant and agree that never hereafter shall either slavery or involuntary servitude exist in their nation otherwise than in the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, in accordance with laws applicable to all the members of said tribe alike. They further agree that all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months, and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees: Provided, That owners of slaves so emancipated in the Cherokee Nation shall never receive any compensation or pay for the slaves so emancipated. – Article 9 of The Treaty Of 1866[38]

Other nations of the Five Civilized Tribes also signed treaties with the U.S. government in 1866 with articles concerning their respective Freedmen and the abolishing of slavery.[39] While the Chickasaw Nation was the sole tribe that refused to include Freedmen as citizens, the Choctaw Nation formally granted citizenship to Choctaw and Chickasaw Freedmen by adoption in 1885 after considerable tribal debate.[40]

The Cherokee Nation Constitution was amended in a special convention on November 26, 1866. The constitutional amendments removed all language excluding people of African descent and reiterated the treaty's language concerning the Freedmen. The constitution also reiterated the treaty's six-month deadline for Freedmen to return to the Cherokee Nation in order to be counted as citizens.[41] Essentially, Cherokee and other tribal freedmen were allowed the choice to reside as citizens with the tribes, or to have United States citizenship in United States territory outside the tribal nations.

All native born Cherokees, all Indians, and whites legally members of the Nation by adoption, and all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months from the 19th day of July, 1866, and their descendants, who reside within the limits of the Cherokee Nation, shall be taken and deemed to be, citizens of the Cherokee Nation. – 1866 Amendments to Article 3, Section 5 of the 1836 Cherokee Nation Constitution[42]

Assimilation and resistance

Following the recognition of the 1866 treaty, efforts were made by the Cherokee Nation and other nations to incorporate the Freedmen. As citizens of the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen were allowed to vote in local and national elections. By 1875, the inclusion of Freedmen in political office was established with the first Cherokee Freedman elected to the Cherokee National Council.

During the 1870s, several segregated Freedmen schools were established, with seven primary schools in operation by 1872. It was not until 1890 that a high school, Cherokee Colored High School, was established near Tahlequah. The Cherokee Nation typically did not fund these schools at a level comparable to those for Cherokee children.

Like the resistance of whites to acceptance of freedmen as citizens in the South, many Cherokee resisted inclusion of the Freedmen as citizens. This issue became part of the continuing divisions and internal factionalism within the tribe that persisted after the war. In addition, there were tribal members who resented sharing already scarce resources with their former slaves. There were also economic issues, related to the forced granting of some lands to Freedmen, and later allotment of lands and distribution of monies related to land sales.

1880 census

In 1880, the Cherokee compiled a census to distribute per capita funds related to the Cherokee Outlet, a tract of land west of the Cherokee Nation that was sold by the Cherokee in the 1870s. The 1880 census did not include a single Freedmen and also excluded the Delaware and Shawnee, who had been adopted into the Cherokee after being allocated land at their reservation between 1860 and 1867.[43] In the same year, the Cherokee Senate voted to deny citizenship to Freedmen who applied past the six-month deadline specified by the 1866 Cherokee treaty. Yet there were Freedmen who had never left the Nation who were also denied citizenship.[44]

The Cherokee claimed that the 1866 treaty with the U.S. granted civil and political rights to Cherokee Freedmen, but not the right to share in tribal assets. Principal Chief Dennis Wolf Bushyhead (1877–1887) opposed the exclusion of Cherokee Freedmen from distribution of assets and believed that the Freedmen's omission from the 1880 census was a violation of the 1866 treaty. But his veto to pass an act that added a "by blood" requirement for the distribution of assets was overridden by the Cherokee National Council in 1883.

1888 Wallace Roll

In the 1880s the federal government became involved on behalf of the Cherokee Freedmen; in 1888 the US Congress passed An Act to secure to the Cherokee Freedmen and others their proportion of certain proceeds of lands, Oct. 19, 1888, 25 Stat. 608, which included a special appropriation of $75,000 to compensate for failure of the tribe to pay them money owed. Special Agent John W. Wallace was commissioned to investigate and create a roll, now known as the Wallace Roll, to aid in the per-capita distribution of federal money. The Wallace Roll, completed from 1889 to 1897 (with several people working on it)[45] included 3,524 Freedmen.[46]

The Cherokee Nation continued to challenge the rights of the Freedmen. In 1890, by passing "An act to refer to the U.S. Court of Claims certain claims of the Shawnee and Delaware Indians and the freedmen of the Cherokee Nation", Oct. 1, 1890, 26 Stat. 636, the US Congress authorized the U.S. Court of Claims to hear suits by the Freedmen against the Cherokee Nation for recovery of proceeds denied them. The Freedmen won the claims court case that followed, Whitmire v. Cherokee Nation and The United States (1912)[47] (30 Ct. Clms. 138(1895)).

The Cherokee Nation appealed it to the US Supreme Court. It related to treaty obligations of the Cherokee Nation to the United States. The Claims Court ruled that payments of annuities and other benefits could not be restricted to "particular class of Cherokee citizens, such as those by blood." This ruling was upheld by the Supreme Court, thus affirming the rights of Freedmen and their descendants to share in tribal assets.[48]

1894-1896 Kern-Clifton Roll

As the Cherokee Nation had already distributed the funds they had received for sale of the Cherokee Outlet, the U.S. government as co-defendant was obligated to pay the award to the Cherokee Freedmen. It commissioned the Kern-Clifton roll, completed in 1896, as a record of the 5,600 Freedmen who were to receive a portion of the land sale funds as settlement. The payment process took a decade.[46]

1898-1907 Dawes Rolls

Prior to the distribution of proceeds, Congress had passed the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887. It was a measure to promote assimilation of Native Americans in the Indian Territory by requiring the extinguishing of tribal government and land claims; communal lands were to be allotted to individual households of citizens registered as tribal members, in order to encourage subsistence farming according to the European-American model. The U.S. government would declare any remaining lands to be "surplus" to communal Indian needs and allowed it to be bought and developed by non-Native Americans. This resulted in massive losses of land for the tribes.

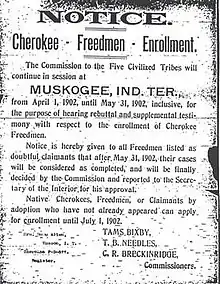

As a part of the act and subsequent bills, the Dawes Commission was formed in 1893 and took a census of the citizens in Indian Territory from 1898 to 1906. The Dawes Rolls, officially known as The Final Rolls of the Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory, listed individuals under the categories of Indians by blood, intermarried Whites, and Freedmen. The rolls were completed in March 1907 and additional citizens were enrolled under an Act of Congress on August 1, 1914. Although Freedmen frequently had Cherokee ancestry and sometimes living Cherokee parents, the Dawes commissioners generally listed all Freedmen or people of visible African features exclusively on the Freedmen Roll, rather than recording an individual's percentage of Cherokee ancestry.[49]

It was not an orderly process. The Dawes Rolls of 1902 listed 41,798 citizens of the Cherokee Nation, and 4,924 persons listed separately as Freedmen. Intermarried whites, mostly men, were also listed separately. The genealogist Angela Y. Walton-Raji said that together, the Five Civilized Tribes had nearly 20,000 Freedmen listed on the Dawes Rolls.[49]

The 1898 Curtis Act, sponsored by U.S. Senator Charles Curtis (Kaw Nation) from Kansas, was also intended to encourage assimilation. It authorized the Dawes Commission to allot funds without the consent of tribal governments, and allowed the federal government to extract taxes from white citizens living in the Indian territories. (American Indians have considered both the Dawes and Curtis acts as restrictions on tribal sovereignty.) The government distributed allotments of land, and there have been many claims of unfair treatment and errors in the registration process.[50] For instance, some 1,659 freedmen listed on the Kern-Clifton roll were not registered on the Dawes Rolls,[46] and therefore lost their Cherokee citizenship rights. As the Cherokee Nation's government was officially dissolved, and Oklahoma became a state (1907), the Cherokee Freedmen and other Cherokee were granted U.S. citizenship.

Numerous activists have criticized inconsistencies in the information collected in the Dawes Rolls. Several tribes have used these as a basis for proving descent in order to qualify for membership. In previous censuses, persons of mixed African-Native American ancestry were classified as Native American.[49] The Dawes Commission set up three classifications: Cherokee by blood, intermarried White, and Freedmen. The registrars generally did not consult with individuals as to how they identified. Overall the Dawes Rolls is incomplete and inaccurate.[51][52][53]

In the later 20th century, the Cherokee and other Native Americans became more assertive about their sovereignty and rights. Issues of citizenship in reorganized tribes was critical to being part of the nation. In testimony as a member of the Cherokee Freedmen's Association, before the Indian Claims Commission on November 14, 1960, Gladys Lannagan discussed specific problems in the records for her family,

I was born in 1896 and my father died August 5, 1897. But he didn't get my name on the [Dawes] roll. I have two brothers on the roll—one on the roll by blood and one other by Cherokee Freedman children's allottees.

She said that one of her paternal grandparents was Cherokee and the other African American.[54]

There have also been cases of mixed-race Cherokee, of partial African ancestry, with as much as 1/4 Cherokee blood (equivalent to one grandparent being full-blood), but who were not listed as "Cherokee by blood" in the Dawes Roll because of having been classified only in the Cherokee Freedmen category. Thus such individuals lost their "blood" claim to Cherokee citizenship despite having satisfied the criterion of having a close Cherokee ancestor.[55]

In 1924, Congress passed a jurisdictional act that allowed the Cherokee to file suit against the United States to recover the funds paid to Freedmen in 1894-1896 under the Kern-Clifton Roll. It held that the Kern-Clifton Roll was valid for only that distribution, and was superseded by the Dawes Rolls in terms of establishing the Cherokee tribal list of membership. With passage of the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946, Congress established a commission to hear cases of Indian claims. Numerous descendants of the 1,659 Freedmen who had been recorded on the Kern-Clifton Roll but not on the Dawes roll, organized to try to correct the exclusion of their ancestors from Cherokee tribal rolls. They also sought payments from which they had been excluded.

Loss of membership

On October 22, 1970, the former Five Civilized Tribes had the right to vote for their tribal leaders restored by Congress via the Principal Chiefs Act. In 1971, the Department of the Interior stated that one of the three fundamental conditions for the electoral process was that voter qualification of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole must be broad enough to include the Freedmen citizens of their respective nations. The Freedmen were issued voter cards by the Cherokee Nation, headed by Principal Chief W. W. Keeler, and participated in the first Cherokee elections since the 1900s as well as subsequent elections.

In the 1970s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began to provide several federal services and benefits, such as free healthcare, to members of federally recognized tribes. Numerous descendants of Cherokee listed as Cherokee by blood on the Dawes Commission Rolls enrolled as new members of the Cherokee Nation. As members of the Cherokee Nation, federal services were also provided to the Cherokee Freedmen. However, certain benefits were limited or unattainable. In a letter to official Jack Ellison in 1974 regarding freedmen eligibility for BIA and Indian Health Service benefits, Ross O. Swimmer, then-Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, stated that the Freedmen citizenry should be entitled to certain health benefits like other enrolled Indians[56]

A new Cherokee Nation constitution, approved by the commissioner of Indian Affairs on September 5, 1975, was ratified by voters on June 26, 1976. Article III, Section 1 of the new constitution defined citizens as those proven by reference to the final Dawes Commission Rolls, including the adopted Delaware and Shawnee.[57]

Efforts to block the Freedmen descendants from the tribe began in 1983 when Principal Chief Swimmer issued an executive order stating that all Cherokee Nation citizens must have a CDIB card in order to vote instead of the previous Cherokee Nation voter cards that were used since 1971. The CDIB cards were issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs based on those listed on the Dawes Commission Rolls as Indians by blood. Since the Dawes Commission never recorded Indian blood quantum on the Cherokee Freedmen Roll or the Freedmen Minors Roll, the Freedmen could not obtain CDIB cards.[58]

Although they were Dawes enrollees, received funds resulting from tribal land sales via the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Whitmire v. Cherokee Nation and United States (1912), and voted in previous Cherokee Nation elections, the Cherokee Freedmen descendants were turned away from the polls and told that they did not have the right to vote. According to Principal Chief Swimmer in a 1984 interview, both the voter registration committee and the tribal membership committee had introduced new rules in the period between 1977 and 1978 that declared that according to the Cherokee Constitution of 1976, an individual must have a "Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood" (CDIB) card from the U.S. government before enrollment or voting rights were allowed.[58] However, Article III of the 1976 constitution had no mention of blood requirements for membership or voting rights.[59]

Swimmer's executive order was analyzed by some observers as one way Swimmer excluded people who were supporting a rival candidate, former deputy chief Perry Wheeler, for Principal Chief.[60][61] After the 1983 Cherokee Nation elections and the re-election of Swimmer, Wheeler and his running mate, Agnes Cowen, initiated a series of legal proceedings such as filing cases with the Cherokee Judicial Appeals Tribunal, petitioning the Bureau of Indian Affairs to conduct an investigation of the election, and filing a case with the US District Court. Wheeler and Cowen alleged that the election was a violation of federal and tribal law and that the Cherokee Freedmen were unjustly removed from voting because they were allies of Wheeler. All cases and subsequent appeals were defeated.[62]

Swimmer's successor and former Deputy Chief, Wilma P. Mankiller, was elected in 1985.[63] In 1988, the Cherokee Registration Committee approved new guidelines for tribal membership that mirrored Swimmer's previous executive order regarding voting requirements.[64] On September 12, 1992, the Cherokee Nation Council unanimously passed, with one member absent, an act requiring all enrolled members of the Cherokee Nation to have a CDIB card. Mankiller had reaffirmed "Swimmer's order on CDIBs and voting."[65] Principal Chief Mankiller signed and approved the legislation.[66] From that point on, Cherokee Nation citizenship was granted only to individuals descended directly from an ancestor on the "Cherokee by blood" rolls of the Dawes Commission Rolls. This completed the disfranchisement of the Cherokee Freedmen descendants.[67]

Activism of the 1940s–2000s

In the 1940s, more than 100 descendants of freedmen from the Wallace Roll, Kern-Clifton Roll, and the Dawes Rolls formed the Cherokee Freedmen's Association. The organization filed a petition with the Indian Claims Commission in 1951 over their exclusion from citizenship. The petition was denied in 1961. The Indian Claims Commission stated that their claims to tribal citizenship were individual in nature and outside the U.S. government's jurisdiction.[68]

The Cherokee Freedmen's Association was faced with two issues regarding their case. On one hand, the Dawes Rolls, a federally mandated tally, was accepted as defining who were legally and politically Cherokee and most of the CFA members were not of Dawes Rolls descent. On the other, the courts saw their claims as a tribal matter and outside of their jurisdiction. Appeals stretched to 1971, but all were denied with only few legal victories to show for their twenty-year effort.[68]

On July 7, 1983, the Reverend Roger H. Nero and four other Cherokee Freedmen were turned away from the Cherokee polls as a result of the newly instituted Cherokee voting policy. A Freedman who voted in the 1979 Cherokee election, Nero and colleagues sent a complaint to the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, claiming discrimination on the basis of race. On June 18, 1984, Nero and 16 Freedmen descendants filed a class action suit against the Cherokee Nation. Principal Chief Ross Swimmer, tribal officials, the tribal election committee, the United States, the office of the President, the Department of the Interior, the Secretary of the Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and three Muskogee, Oklahoma, BIA officials were named as defendants.

The suit sought nearly $750 million (~$1.74 billion in 2021) in damages and asked for the 1983 tribal election to be declared null and void. The court ruled against the plaintiff Freedmen because of jurisdictional issues, with the same ruling made by the Court of Appeals on December 12, 1989. The courts held that the case should have been filed in claims court instead of district court due to the amount asked in the lawsuit. No judgment was made as to the merits of the case itself.

Bernice Riggs, a Freedmen descendant, sued the Cherokee Nation's tribal registrar Lela Ummerteskee in 1998 over the latter denying the former's October 16, 1996 citizenship application. On August 15, 2001, the Judicial Appeals Tribunal (now the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court) ruled in the case of Riggs v. Ummerteskee that while Riggs adequately documented her Cherokee blood ancestry, she was denied citizenship because her ancestors on the Dawes Commission Rolls were listed only on the Freedmen Roll.

In September 2001, Marilyn Vann, a Freedmen descendant, was denied Cherokee Nation citizenship on the same grounds as Bernice Riggs. Despite documented Cherokee blood ancestry from previous rolls, Vann's father was listed only as a Freedman on the Dawes Rolls. In 2002, Vann and other Freedmen descendants started the Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes organization. The group garnered support from other Freedmen descendants as well as support from Cherokee and Non-Cherokee. On May 17, 2005, the Delaware Tribe of Indians, one of two non-Cherokee tribes that are Cherokee Nation members by treaty, unanimously approved a resolution to endorse the organization and has shown support for Freedmen efforts.[69]

2004–2017

Reinstatement and loss of citizenship

On September 26, 2004, Lucy Allen, a Freedmen descendant, filed a lawsuit with the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court, asserting that the acts barring Freedmen descendants from tribal membership were unconstitutional, in the case of Allen v. Cherokee Nation Tribal Council. On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeals Tribunal ruled in Allen's favor in a 2–1 decision that the descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen were Cherokee citizens and were allowed to enroll in the Cherokee Nation.[70] This was based on the facts that the Freedmen were listed as members on the Dawes Rolls and that the 1975 Cherokee Constitution did not exclude them from citizenship or have a blood requirement for membership.[71][72] This ruling overturned the previous ruling in Riggs v. Ummerteskee. More than 800 Freedmen descendants have enrolled in the Cherokee Nation since the ruling was made[73] – out of up to 45,000 potentially eligible people.[74]

Chad "Corntassel" Smith, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, stated his opposition to the ruling after it was announced. Smith called for a constitutional convention or referendum petition to amend the tribal constitution to deny citizenship to the Cherokee Freedmen descendants.[75] During a meeting on June 12, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council voted in a 13–2 decision to amend the constitution to restrict Cherokee citizenship to descendants of persons listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Rolls. It rejected a resolution calling for a special election on the issue.[76]

Supporters of the special election, including former Cherokee Nation deputy chief John Ketcher and Cherokee citizens siding with Smith, circulated a referendum petition for a vote to remove the Freedmen descendants as members.[77] Chief Smith announced that the issue of the membership for Cherokee Freedmen was being considered for a vote related to proposed amendments to the Cherokee Nation Constitution.

Freedmen descendants opposed the election. Vicki Baker filed a protest in the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court over the legality of the petition and allegations of foul play involved in the petition drive.[78] Though the Cherokee Supreme Court ruled against Baker, two justices in the Cherokee Supreme Court, Darrell Dowty and Stacy Leeds, filed separate dissenting opinions against the ruling. Justice Leeds wrote an 18-page dissent concerning falsified information in the petition drive and fraud by Darren Buzzard and Dwayne Barrett, two of the petition's circulators. Leeds wrote,

In this initiative petition process, there are numerous irregularities, clear violations of Cherokee law, and it has been shown that some of the circulators perjured their sworn affidavits. I cannot, in good conscience, join in the majority opinion.[79]

Despite the justices' dissent and the removal of 800 signatures from the petition, the goal of 2,100 signatures was met.

Jon Velie, attorney for the Freedman descendants, filed a motion for a preliminary injunction in the Vann action in US District Court. Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr. ruled against the Freedmen descendants' motion to halt the upcoming election because the election may not have voted out the Freedmen. After a few delays, the tribe voted on March 3, 2007, on whether to amend the constitution to exclude the Cherokee Freedmen descendants from citizenship.[80][81] Registered Cherokee Freedmen voters were able to participate in the election. By a 76% (6,702) to 24% (2,041) margin out of a total of 8,743 votes cast by registered voters, the referendum resulted in membership rules that excluded the Cherokee Freedmen descendants.[82] The turnout was small; by comparison, the previous Cherokee general election turnout had totaled 13,914 registered voters.[41]

The Freedmen descendants protested their ouster from the tribe with demonstrations at the BIA office in Oklahoma and at the Oklahoma state capitol.[83][84] Due to the issues of citizenship in the election and the resulting exclusion of freedmen descendants, the Cherokee Nation was criticized by United States groups such as the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Congress of Black Women. On March 14, 2007, twenty-six members of the Congressional Black Caucus sent a letter to Carl J. Artman, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, urging the Bureau of Indian Affairs to investigate the legality of the March 3rd election.[85][86]

BIA controversy and temporary reinstatement

The 2007 election was criticized for having been conducted under a constitution that was not approved by the Secretary of the Interior.[87] On May 22, 2007, the Cherokee Nation received notice from the BIA that the Cherokee Nation's amendments to the 1975 Cherokee Nation Constitution were rejected because they required BIA approval, which had not been obtained. The BIA also stated concerns that the Cherokee Nation had excluded the Cherokee Freedmen from voting for the constitutional amendments, since they had been improperly shorn of their rights of citizenship years earlier and were not allowed to participate in the constitutional referendum.

This is considered a violation of the 1970 Principal Chiefs Act, which requires that all tribal members must vote. Chief Smith disbanded the Judicial Appeals Tribunal and created a new Cherokee Supreme Court under the new Constitution. A question remains regarding the legitimacy of the Court as the United States has not approved the Constitution as required under the previous Cherokee Constitution.

According to Chief Smith, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 overrode the 1970 Principal Chiefs Act, and the Cherokee Nation had the sovereign right to determine its citizenship requirements. Smith stated that the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation could take away the approval authority it had granted the federal government and that the Nation will abide by the court's decision.[88][89] Despite the ruling, the issue of amending the process of federal approval was placed on the ballot for the June 23, 2007 general election. Cherokee voters approved the amendment to remove federal oversight by a 2–1 margin, but the BIA still has to approve. Jeanette Hanna, director of the BIA's Eastern Oklahoma Regional Office, said that the regional office has recommended approval of the vote on removal of Secretarial oversight.[90]

Heading into the 2007 election, the Cherokee Nation was not permitting the Freedmen to vote. Attorney Jon Velie again filed a motion for preliminary injunction. On May 15, 2007, Cherokee District Court Judge John Cripps signed an order for the Cherokee Freedmen descendants to be temporarily reinstated as citizens of the Cherokee Nation while appeals are pending in the Cherokee Nation court system. This was due to an injunction filed by the Freedmen descendants' court-appointed attorney for their case in tribal court. The Cherokee Nation's Attorney General Diane Hammons complied with the court order.[91][92] Velie, on behalf of Marilyn Vann and six Freedmen descendants, argued the late actions that protected 2,800 Freedmen (but not all who were entitled to citizenship) were insufficient, but Judge Henry Kennedy denied the motion. On June 23, 2007, Chad Smith was reelected for a four-year term as Principal Chief with 58.8% of the vote.

Congressional issues

On June 21, 2007, US Rep. Diane Watson (D-California), one of the 25 Congressional Black Caucus members who signed a letter asking the BIA to investigate the Freedmen situation, introduced H.R. 2824. This bill seeks to sever the Cherokee Nation's federal recognition, strip the Cherokee Nation of their federal funding (estimated $300 million annually), and stop the Cherokee Nation's gaming operations if the tribe does not honor the Treaty of 1866. H.R. 2824 was co-signed by eleven Congress members and was referred to the Committee Of Natural Resources and the Committee Of The Judiciary.

Chief Smith issued a statement saying that the introduction of this bill is "really a misguided attempt to deliberately harm the Cherokee Nation in retaliation for this fundamental principle that is shared by more than 500 other Indian tribes." The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) expressed their disapproval of the bill.[93]

On September 26, 2008, Congress cleared the housing bill H.R. 2786. The reauthorization of the Native American Housing and Self-Determination Act included a provision stating that the Cherokee Nation can receive federal housing benefits as long as a tribal court order allowing the citizenship for Cherokee Freedmen descendants is intact or some settlement is reached in the citizenship issue and litigation involving the Cherokee Freedmen descendants.[94] The House Of Representatives version of the bill would have denied funds unless the Freedmen descendants were restored to citizenship. The Senate version of the bill had no mention of the Cherokee Nation or the Cherokee Freedmen descendants. Paul Lumley, executive director of the National American Indian Housing Council (NAIHC), said that the NAIHC worked with members of the Congressional Black Caucus to create a compromise, resulting in the addition of the Cherokee Freedmen stipulation in the bill.[95]

Federal court proceedings

Marilyn Vann and four Freedmen descendants filed a case with the United States Federal Court over the Cherokee Nation's disfranchisement of the Freedmen descendants. Efforts have been made by the Cherokee Nation to dismiss the federal case.

On December 19, 2006, Federal Judge Henry Kennedy ruled that the Freedmen descendants could sue the Cherokee Nation for disfranchisement.[96] The Cherokee Nation's administration appealed the decision on the grounds that as a sovereign nation, the tribe is protected by sovereign immunity and cannot be sued in US court. On July 29, 2008, the Washington D.C. Circuit Court Of Appeals unanimously ruled that the Cherokee Nation was protected by sovereign immunity and could not be listed as a defendant in the lawsuit. But, it stated that the Cherokee Nation's officials were not protected by the tribe's sovereign immunity, and Freedmen descendants could proceed with a lawsuit against the tribe's officers.[97]

The ruling also stated the 13th Amendment and the Treaty of 1866 whittled away the Cherokee right to discriminate against the Freedmen descendants. The ruling means that the case will go back to district court. Velie stated this was a great victory for the Freedmen and Indian people who can bring actions against the elected officials of their Native Nations and the United States.

In February 2009, the Cherokee Nation filed a separate Federal lawsuit against individual Freedmen in what some called an attempt at "venue shopping". The case was sent back to Washington to join the Vann case. "On July 2, the Honorable Judge Terrance Kern of the Oklahoma Northern District Court transferred the Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al case that was filed in his court in February 2009 to D.C. Already awaiting judgment in D.C. is the case of Marilyn Vann et al v. Ken Salazar filed in August 2003."[98] Kern would not hear the Nash case, filed by the Cherokee Nation, due to the cases resembling each other in parties and the subject matter of Freedmen citizenship; in addition, the first-to-file rule meant that the Vann case needed to be heard and settled before any court heard the Nash case.

As the Cherokee Nation waived its sovereign immunity to file the Cherokee Nation v. Nash case, it is now subject to the possibility of Judge Kennedy's enjoining the Cherokee Nation to the original case, after they had won immunity. "Finally, the Court is not, as argued by the Cherokee Nation, depriving the Cherokee Nation of 'the incidents of its sovereign immunity' by transferring this action pursuant to the first to file rule. The Cherokee Nation voluntarily filed this action and waived its immunity from suit. It did so while the D.C. Action was still pending."[99]

In October 2011, Judge Kennedy dismissed the Vann case for technical reasons and transferred the Nash cash back to Federal District Court in Tulsa, OK. Velie informed the Court in a status Conference report that the Freedmen descendants will appeal the Vann dismissal. The date for the appeal was November 29, 2011.

2011

On January 14, 2011, Cherokee District Court Judge John Cripps ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the Raymond Nash et al v. Cherokee Nation Registrar case, reinstating Cherokee Nation citizenship and enrollment to the Freedmen descendants. Cripps ruled that the 2007 constitutional amendment that disenrolled the Freedmen descendants was void by law because it conflicted with the Treaty of 1866 that guaranteed their rights as citizens.[100]

The Cherokee Nation held general elections for Principal Chief between challenger Bill John Baker, a longtime Cherokee Nation councilman, and Chad Smith, the incumbent Principal Chief, on June 24, 2011. Baker was declared the winner by 11 votes. But, the Election Committee determined that the next day that Smith had won by 7 votes. In a recount, Baker was declared the winner by 266 votes, but Smith appealed to the Cherokee Supreme Court. It ruled that a winner could not be determined with mathematical certainty.

A special election was scheduled for September 24, 2011. On August 21, 2011, prior to the scheduling of the Cherokee special election, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court reversed the January 14 decision of the Cherokee District Court, resulting in the disenrollment of the Freedmen descendants. Justice Darell Matlock Jr. ruled that the Cherokee people had the sovereign right to amend the Cherokee Nation constitution and to set citizenship requirements. The decision was 4 to 1 with Justice Darrell Dowty dissenting.[101]

Many observers questioned the timing of the decision as the Cherokee Freedmen voters, who voted in the June general election, were disenfranchised going into the special election. The decision also removed the injunction of the District Court which had kept the Freedmen descendants in the Nation. On September 11, 2011, the Cherokee Nation sent letters to 2800 Freedmen descendants informing them of their disenrollment.[102] In response, Jon Velie and the Freedmen descendants filed another motion for preliminary injunction in federal district court asking to reinstate their rights for the election.[103]

As a result of the Cherokee Supreme Court ruling, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development suspended $33 million in Cherokee Nation funds while it studied the issue of the Freedmen descendants' disenrollment.[102] Larry Echo Hawk, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior, sent a letter to acting Principal Chief Joe Crittenden stating that the Department of the Interior never approved the Cherokee constitutional amendments that excluded the Freedmen descendants from tribal membership. Echo Hawk stated said that the September 24, 2011 election would be considered unconstitutional if the Freedmen descendants were excluded from voting, as guaranteed by the Treaty of 1866.[104]

On September 14, Cherokee Attorney General Diane Hammons recommended reopening the case with the previous reinstatement to be applied while oral arguments would be scheduled.[105][106] In a preliminary federal court hearing on September 20, 2011, Judge Henry Kennedy heard arguments from Jon Velie representing the Freedmen descendants, Amber Blaha representing the U.S. government, and Graydon Dean Luthey, Jr. representing the Cherokee Nation. Following arguments, the parties announced that the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen plaintiffs, and U.S. government had come to an agreement to allow the Freedmen descendants to be reinstated as citizens with the right to vote, with voting to continue two additional days. The Cherokee Nation was to inform the Freedmen of their citizenship rights no later than September 22.

On September 23, 2011, Velie returned to the Court with the other parties, as virtually none of the Freedmen descendants had received notification with the election happening the next day. Judge Kennedy signed an additional agreed upon Order between the parties requiring additional time for absentee ballots for Freedmen descendants and five days of walk-in voting for all Cherokee.[107]

In October 2011, Bill John Baker was inaugurated as Principal Chief after the Cherokee Supreme Court rejected an appeal of the election results by former chief Chad Smith.[108]

Motions, developments and hearings 2012 to 2014

The Cherokee Nation amended their complaint in May 2012 and as a response,[109] on July 2, 2012, the US Department of the Interior filed a counter lawsuit against the Cherokee Nation in U.S. District Court in Tulsa, Oklahoma seeking to stop the denial of tribal citizenship and other rights to the Freedmen.[110] The Freedmen filed counterclaims against certain Cherokee Nation Officers and the Cherokee Nation with cross-claims against the Federal Defendants.[109]

On October 18, 2012, the Vann case was heard by the United States District Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. On December 14, 2012, the court reversed the initial finding of the lower court, stating "The Ex parte Young doctrine allows suits for declaratory and injunctive relief against government officials in their official capacities – notwithstanding the sovereign immunity possessed by the government itself. The Ex parte Young doctrine applies to Indian tribes as well". It remanded the case back to the lower courts.[111] In March, 2013 a request by the tribe to reconsider the decision was denied.[112]

On September 13, 2013, the parties to Vann and Nash, including the Cherokee, jointly petitioned the United States District Court for the District of Columbia to resolve by summary judgment the question of whether the Freedmen are entitled to equal citizenship in the Cherokee Nation under the Treaty of 1866.[109] A hearing was scheduled for late April, 2014[113] but occurred on May 5, 2014. After reviewing the motion for summary judgment submitted in January by the Department of the Interior, Judge Thomas F. Hogan stated that "he was skeptical the treaty allows the tribe to change its constitution to require Indian blood for CN [Cherokee Nation] citizenship." The hearing was the first during the 11-year controversy to look at the merits, rather than procedural issues.[114]

Reinstatement of citizenship

On August 30, 2017, the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants and the U.S. Department of the Interior in Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al. and Marilyn Vann et al.. The court ruled that according to Article 9 of the Cherokee Treaty of 1866, the Cherokee Freedmen descendants have present rights to citizenship that is coextensive with the rights of native Cherokees.[115] Senior U.S. District Judge Thomas F. Hogan stated that while the Cherokee Nation has the right to determine citizenship, it must do so with respect to both native Cherokees and the descendants of Cherokee Freedmen.[116]

In a statement on August 31, Cherokee Nation Attorney General Todd Hembree stated that no appeal will be filed against the ruling. Further, citizenship applications from Freedmen descendants have been accepted and processed since the ruling.[117] In a public statement, Cherokee Freedmen lead counsel Jon Velie stated that the ruling was not only a victory for the Freedmen in regaining their citizenship, but also a victory for Native Americans as the federal courts have enforced treaty rights of citizenship while maintaining tribes and elected officials' rights to determine citizenship and self-determination.[118]

Reactions to the controversy

A number of Cherokee Freedmen descendants feel that they have been gradually pushed out of the Cherokee Nation, and that the process has left each generation less aware of its rights and its history. As Freedman activist Reverend Roger H. Nero said in 1984, "Over the years they [Cherokee Nation officials] have been eliminating us [Freedmen] gradually. When the older ones die out, and the young ones come on, they won't know their rights. If we can't get this suit, they will not be able to get anything".[119] Freedmen descendant and journalist Kenneth Cooper said, "By rejecting a people whose history is so bound up with their own, the Cherokees are engaging in a massive case of denial. The history of every family descended from Freedmen reflects close relations with Cherokees, down to some last names still in use today."[120]

Some Cherokee who oppose membership for Freedmen descendants support Chief Smith's position: that the Freedmen are not Cherokee citizens because their ancestors were listed on the Freedmen Roll of the Dawes Rolls and not on the "Cherokee By-Blood" Roll (although some were in fact of Cherokee blood). Smith and supporters claim that the Freedmen and their descendants have not been active in the tribe for 100 years, the Freedmen were compensated for slavery by their Dawes land allotments and not tribal membership, and they were forced on the tribe by the US under the Treaty of 1866. Some Cherokee believe the Freedmen descendants only want to share in the tribe's new resources and Cherokee Nation's federally funded programs.[121]

Other Cherokee argue the case on the basis of tribal sovereignty, saying that Cherokee Nation members have the sovereign right to determine qualifications for membership. Diane Hammons, former Attorney General for the Cherokee Nation, stated, "We believe that the Cherokee people can change our Constitution, and that the Cherokee citizenry clearly and lawfully enunciated their intentions to do so in the 2007 amendment."[122]

Those supporting membership of Freedmen descendants believe they have a rightful place in Cherokee society based on their long history in the tribe before and after forced removal, with a history of intermarriage and active members. In addition, they cite as precedent the legal history, such as the Treaty Of 1866, the 1894 Supreme Court case of Cherokee Nation vs. Journeycake,[123] and the 1975 Cherokee Constitution. Ruth Adair Nash, a Freedmen descendant from Bartlesville, Oklahoma, carries her Cherokee citizenship card, which she was issued in 1975.

Some Cherokee by blood have supported full citizenship for Freedmen. David Cornsilk, a founder of the grassroots Cherokee National Party in the 1990s and editor of the independent newspaper The Cherokee Observer, served as lay advocate in the Lucy Allen case. Cornsilk believed that the Cherokee had to honor their obligations as a nation and get beyond identification simply as a racial and ethnic group. He was aware that many of the people are mixed-race, with an increasingly high proportion of European ancestry. He believed they could not exclude the freedmen. He also believed that the nation had to encompass the residents of the area, including freedmen descendants, through its political jurisdiction. This would reduce the racial issues so that the Cherokee acted as a nation and stood "behind its identity as a political entity."[124] Other Cherokee have expressed solidarity with freedmen due to their similarities of religion (Southern Baptist) and the sense of community found among freedmen.[125]

Some individual Cherokee and Freedmen have not been aware of the issue. Dr. Circe Sturm, professor, wrote in her book Blood Politics that many Freedmen descendants had little sense of the historic connection with the Cherokee and are ambivalent about getting recognized.[12] Cherokee members have also been ignorant of the historic issues. Cara Cowan Watts, a tribal council member who opposed membership for Freedmen descendants, said in 2007 that she didn't know anything about the Freedmen or their history before the court case.[126] Chief Smith said, "A lot of Cherokee don't know who the Freedmen are," and that he was not familiar with them when growing up.[49]

In a June 2007 message to members of United Keetoowah Band Of Cherokee, Principal Chief George Wickliffe expressed his concern about threats to sovereignty because of this case. He said that the Cherokee Nation's refusal to abide by the Treaty of 1866 threatened the government-to-government relationships of other Native American nations, which had struggled to make the US live up to its treaty obligations.[127]

One of several issues that have risen from the controversy is the issue of blood lineage and government records in regards to determining tribal membership. Historians have noted that before the Dawes Commission, the Cherokee have included people from previous rolls and people of non-Cherokee descent as members of the nation, from former captives to members by adoption. The Delaware and Shawnee tribes, two non-Cherokee tribes, are members of the Cherokee Nation via the Delaware Agreement of 1867 and the Shawnee Agreement of 1869. Another issue is that of a tribe's breaking a treaty protected by Article Six of the United States Constitution. Daniel F. Littlefield Jr., director of the Sequoyah Research Center at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, stated that the Treaty of 1866 granted freedmen their rights as citizens, and the case should not be made into a racial issue.[128]

Race is another issue. Taylor Keen, a Cherokee Nation tribal council member, said,

Historically, citizenship in the Cherokee Nation has been an inclusive process; it was only at the time of the Dawes Commission there was ever a racial definition of what Cherokee meant. The fact that it was brought back up today certainly tells me that there is a statute of racism.[3]

Cherokee Nation citizen Darren Buzzard, one of the circulators of the 2006 petition, wrote a letter to Cherokee Councilwoman Linda O'Leary, with passages which many observers deemed to be racist and bigoted. Circulated widely on the Internet, the letter was quoted in numerous articles related to the Freedmen case.[49][129]

Oglala Lakota journalist Dr. Charles "Chuck" Trimble, principal founder of the American Indian Press Association and former executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, criticized the Cherokee Supreme Court's August 2011 ruling and compared it to the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision.[130]

In 2021, the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court ruled to remove the words "by blood" from its constitution and other legal doctrines because "[t]he words, added to the constitution in 2007, have been used to exclude Black people whose ancestors were enslaved by the tribe from obtaining full Cherokee Nation citizenship rights."[6] However, all citizenship is still based on finding an ancestor tied to the Dawes Rolls, which is not without its own controversy apart from blood quantum.[131][132] Some people of descent are still excluded, like the author Shonda Buchanan who states in her memoir Black Indian that she has ancestors on Cherokee Rolls that were not the Dawes, so would thus still not be recognized.[133] Basing citizenship off the Dawes Rolls and other rolls is what scholar Fay A. Yarbrough calls "dramatically different from older conceptions of Cherokee identity based on clan relationship’s, in which individuals could be fully Cherokee without possessing any Cherokee ancestry" and that by the tribe later "developing a quantifiable definition of Cherokee identity based on ancestry", this "would dramatically affect the process of enrollment late in the nineteenth century and the modern procedure of obtaining membership in the Cherokee Nation, both of which require tracing and individuals’ lineage to a ‘Cherokee by blood.’" Thus, the Dawes Roll itself still upholds "by blood" language and theory.[134]

Representation in other media

- By Blood (2015) is a documentary directed by Marcos Barbery and Sam Russell about the Cherokee Freedmen controversy and the issues related to tribal sovereignty. It screened at the deadCenter Film Festival in Oklahoma City in June 2015, and is being shown on the festival circuit.[135] Barbery previously published an article on the controversy.[136]

See also

References

- Roberts, Alaina E. (2021). I've been here all the while : Black freedom on Native land. Philadelphia. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8122-9798-0. OCLC 1240582535.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Cherokee leader wants to overturn freedmen decision". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- Daffron (2007)

- Nathan Koppel, "Tribe Fights With Slaves' Kin", Wall Street Journal, 16 July 2012

- Kyle T. Mays, "Still Waiting: Cherokee Freedman Say They're Not Going Anywhere", Indian Country Today, 20 July 2015, accessed 1 January 2016

- Kelly, Mary Louise (February 25, 2021). "Cherokee Nation Strikes Down Language That Limits Citizenship Rights 'By Blood'". NPR. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- McLoughlin, William G. After the Trail of Tears: The Cherokee's Struggle for Sovereignty 1839–1880

- Newton, Josh. "Newton, Josh. "Monument To History", Tahlequah Daily Press, May 20, 2008 (Accessed August 20, 2008)". Tahlequahdailypress.com. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Jackson, Tesina. "Stick Ross: 'Tahlequah pioneer and civic leader", Cherokee Phoenix, March 3, 2011 (Accessed December 21, 2011)". Cherokeephoenix.org. 2011-03-03. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Koerner, Brendan I. "Blood Feud", Wired Magazine, Issue 13.09, September 2005". Wired.com. 2009-01-04. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Ray (2007) p. 411

- Sturm (1998) p251

- for a full discussion, see Perdue (1979)

- Russell (2002) p70

- Russell (2002) p. 70. Ray (2007) p. 423, says that the peak of enslavement of Native Americans was between 1715 and 1717; it ended after the Revolutionary War.

- Sturm (1998) p231

- Mcloughlin (1977) p682

- Mcloughlin (1977) 690, 699

- Littlefield (1978) p68

- Mcloughlin (1977) p690

- "Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom, University of California Press, 2nd edition, 2015, p. 16" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-20. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- Kathy-Ann Tan, Reconfiguring Citizenship and National Identity in the North American Literary Imagination, Detroit: Wayne State University, 2015, pp 245-246

- Miles (2015), p. 19

- Miles (2009)

- Sturm (1998) p.60

- Littlefield (1978) p9

- Mcloughlin (1977) p127

- "Duncan, James W. "INTERESTING ANTE-BELLUM LAWS OF THE CHEROKEES, NOW OKLAHOMA HISTORY," Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 6, No. 2 June 1928 (Accessed 13 July 2007)". Digital.library.okstate.edu. 1928-06-02. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Davis, J. B. "SLAVERY IN THE CHEROKEE NATION," Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 11, No. 4 December 1933 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Digital.library.okstate.edu. 1933-12-04. Archived from the original on 2015-03-10. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Mcloughlin (1977) p135

- Taylor, Quintard. "Cherokee Emancipation Proclamation (1863)", The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. (retrieved 10 Jan 2010)

- "Miles (2009) p179"

- Foster, George E. (January 1888). "Abolition of Slavery by the Cherokees". The Century, p. 638

- Mcloughlin (1977) p383

- Mcloughlin (1977) p208-209

- Sturm (1998) p232

- Reports from Gen. Sanborn to the Secretary of the Interior, accessed 17 September 2011

- Oklahoma State University Library. ""Cherokee Treaty of 1866", Oklahoma State University Digital Library, accessed 11 July 2011. See Sturm (1998) and in Ray (2007)". Digital.library.okstate.edu. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "The text of the treaties is available from tulsalibrary.org as of July 22, 2012". Guides.tulsalibrary.org. 2012-12-07. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "1885 Choctaw & Chickasaw Freedmen Admitted To Citizenship". Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Steve Russell, "Tsunami Warning from the Cherokee Nation", Indian Country Today, 14 September 2011, accessed 20 September 2011

- "Text of the convention can be accessed as of July 11, 2007. See Sturm (1998) and Ray (2007)". Digital.library.okstate.edu. 1933-12-04. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Sturm (1998) p. 234.

- Sturm (1998) p. 75.

- "Wallace Roll of Cherokee Freedmen in Indian Territory", National Archives

- Sturm (1998) p. 235

- "US Supreme Court decision for "Whitmire v. Cherokee Nation and The United States", Case 223 U.S. 108, findlaw.com Accessible as of August 20, 2008". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Sturm (1998) p235 referring to Plaintiff's Statement, Nero, 1986

- "Knickmeyer, Ellen. "Cherokee Nation To Vote on Expelling Slaves' Descendants", Washington Post, 3 March 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Washingtonpost.com. March 3, 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- see Debo 1940

- BROOKE JARVIS (2017). "Who Decides Who Counts as Native American?". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Celia E. Naylor (2009). African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807877548. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Kent Carter (2009). The Dawes Commission and the Allotment of the Five Civilized Tribes, 1893-1914. Ancestry Publishing. ISBN 9780916489854. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- Sturm (1998) p246

- Sturm (1998) pp. 247-250

- Sturm (1998)

- 1976 Cherokee Constitution (Accessible as of August 9, 2018)

- Ray, S. Alan (2007). "A Race or a Nation? Cherokee National Identity and the Status of Freedmen's Descendants". Michigan Journal of Race & Law. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Law School. 12 (2): 411. ISSN 1095-2721. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Sturm (1998), p. 239.

- Saunt, Claudio (2006-02-21). "Saunt, Claudio, "Jim Crow And The Indians", Salon, 21 February 2006 (accessible as of July 9, 2008)". Salon.com. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Sturm (1998) p183

- Sturm (2002), p. 183

- Sturm (1998) p179

- "Council of the Cherokee Nation - File #: R-21-88". cherokee.legistar.com.

- King, Thomas (2012). The Inconvenient Indian. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816689767.

- "Council of the Cherokee Nation - File #: LA-06-92". cherokee.legistar.com.

- Sturm (1998) p240

- Sturm (1998) p. 238-239

- "Delaware Tribe Shows Support For Freedmen". Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- "Ray (2007) p390, also discussed at Lucy Allen v. Cherokee Nation decision". Cornsilks.com. 1962-10-09. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Ray (2007) p390-392, also discussed at "Cherokee Freedmen win tribal citizenship lawsuit" indianz.com, March 8, 2006 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Indianz.com. 2006-03-08. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Text of the 1975 Cherokee Nation Constitution can be accessed as of July 8, 2008". Thorpe.ou.edu. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ""About 800 Cherokee Freedmen enrolled since decision", indianz.com, May 1, 2006 (Accessible as of July 27, 2007". Indianz.com. 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Ray (2007) p392

- "Cherokee chief wants Freedmen out of tribe", Indianz.com, 15 March 2006, accessed 20 August 2008

- <f>Ray (2007) p392-393

- Ray (2007) p393

- ""Cherokee court hears dispute over freedmen vote", indianz.com, November 27, 2006 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Indianz.com. 2006-11-27. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Chavez, Will. "Leeds dissent points to initiative petition irregularities". Cherokee Phoenix, January 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007".

- Morris, Frank (2007-02-21). "Cherokee Tribe Faces Decision on Freedmen". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- Stogsdill, Sheila K. "Cherokee Nation votes to remove descendants of Freedmen". Archived from the original on 2011-11-25. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- Ray (2007) p394

- "Ruckman, S. E. "Freedmen supporters picket BIA", Tulsa World, April 7, 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Tulsaworld.com. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- Houghton, Jaclyn (2007-03-27). "Houghton, Jaclyn "Freedmen descendants hold rally, march", Edmond Sun, March 27, 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007". Edmondsun.com. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- "Press release can be read at Ms. Watson's website as of July 13, 2007 at "Rep. Watson & Black Caucus Members Register Outrage Over Blatant Discrimination by Cherokee Nation"". Archived from the original on July 29, 2007.

- It was discussed at "Congressional Black Caucus backs Freedmen", indianz.com, March 14, 2007 (Accessible as of July 13, 2007

- ""BIA rejects 2003 Cherokee Nation constitution", indianz.com, May 27, 2007 (Accessible as of July 10, 2008". Indianz.com. 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2012-12-19.