Chess in the arts

Chess became a source of inspiration in the arts in literature soon after the spread of the game to the Arab World and Europe in the Middle Ages. The earliest works of art centered on the game are miniatures in medieval manuscripts, as well as poems, which were often created with the purpose of describing the rules. After chess gained popularity in the 15th and 16th centuries, many works of art related to the game were created. One of the best-known,[1] Marco Girolamo Vida's poem Scacchia ludus, written in 1527, made such an impression on the readers that it singlehandedly inspired other authors to create poems about chess.[1]

In the 20th century, artists created many works related to the game, sometimes taking their inspiration from the life of famous players (Vladimir Nabokov in The Defense) or well-known games (Poul Anderson in Immortal Game, John Brunner in The Squares of the City). Some authors invented new chess variants in their works, such as stealth chess in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series or Tri-Dimensional chess in the Star Trek series.

History

10th to 18th century

Palatine Chapel in the Norman Palace in Palermo you can admire the first painting of a chess game that is known to the world. The work dates from around 1143 and the artists who created the Muslim players were chosen by the Norman king of Sicily Roger II of Hauteville, who erected the church.

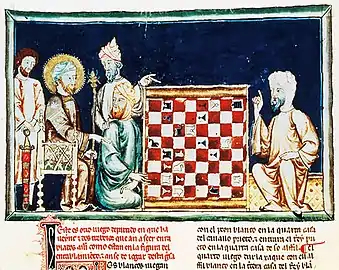

The earliest known reference to chess in a European text is a Medieval Latin poem, Versus de scachis. The oldest manuscript containing this poem has been given the estimated date of 997.[2] Other early examples include miniatures accompanying books. Some of them have high artistic value. Perhaps the best known example is the 13th-century Libro de los juegos. The book contains 151 illustrations, and while most of them are centered on the board, showing problems, the players and architectural settings are different in each picture.[3]

Another early illustrated text is the Book of the customs of men and the duties of nobles or the Book of Chess (Latin: Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium super ludo scacchorum) which is based on the sermons of Jacopo da Cessole and was first published in 1473.[4]

The pieces illustrating chess problems in Luca Pacioli's manuscript On the Game of Chess (Latin: De ludo scacchorum, c. 1500) are described as "futuristic even by today's standards"[5] and may have been designed in collaboration with Leonardo da Vinci.[6]

After chess became gradually more popular in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, especially in Spain and Italy, many artists began writing poems using chess as a theme.[7] Chess of love (Catalan: Scachs d'amor), written by an unknown artist in the end of the 15th century, describes a game between Mars and Venus, using chess as an allegory of love. The story also serves as a pretence to describe the rules of the game. De ludo scacchorum (unrelated to the manuscript mentioned above) by Francesco Bernardino Caldogno, also created at that time, is a collection of gameplay advice, presented in poetic fashion.[8][9]

One of the most influential[1] works of chess-related art is Marco Girolamo Vida's Scaccia ludus (1527), centered on a game played between Apollo and Mercury on Mount Olympus. It is said that, because of its high artistry, the poem made a great impression on anyone who read it, including Desiderius Erasmus.[1] It also directly inspired at least two other works.[10] The first is Jan Kochanowski's poem Chess (c. 1565), which describes the game as a battle between two armies, while the second is William Jones' Caissa, or the game of chess (1772). The latter poem popularised the pseudo-ancient Greek dryad Caïssa to be the "goddess of chess".[10]

19th century onwards

Since the 19th century, artists have been creating novels and – since the 20th century – films related to chess. Sometimes, they are inspired by famous games, like John Brunner's The Squares of the City, structured after the famous match between Wilhelm Steinitz and Mikhail Chigorin; Poul Anderson's short story Immortal Game, inspired by the 1851 game played by Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky (which also appears in the film Blade Runner); or Waldemar Łysiak's Szachista (Polish: The Chess Player), centered on a game played between Napoleon Bonaparte and The Turk. The game Frank Poole versus HAL 9000 from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey is also based on an actual match, albeit not widely known.[11]

Other artists have drawn their inspiration from the life of players. Vladimir Nabokov wrote The Defense after learning about Curt von Bardeleben,[12] while the musical Chess was loosely based on the life of Bobby Fischer.[13] Some authors invented new chess variants in their works, such as stealth chess in Terry Pratchett's Discworld series or Tri-Dimensional chess in the Star Trek series.

Another connection between art and chess is the life of Marcel Duchamp, who almost fully suspended his artistic career to focus on chess in 1923.[14] Salvador Dalí and Man Ray were also chess players and both designed chess sets.[15] The three artists played chess together, and one of the chess sets designed by Dalí is called Echecs (Hommage à Marcel Duchamp).[16][17] Duchamp's 1910 painting The Chess Game depicts his brothers Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Jacques Villon playing chess in the garden of Villon's studio.[18] Another Duchamp painting from the following year again depicts his brothers at the chess table.[19] Duchamp wrote a book titled Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled which was published in 1932.[20] Man Ray and Duchamp are seen playing chess in René Clair's film Entr'acte.[21] A book titled Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess was published in 2009.[22]

Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris were also chess players, and both made many references to the game in their work.[23][24]

The design of Bauhaus professor Josef Hartwig's early 1920s chess set uses the shape of each piece to indicate its permitted movement.

Artists such as Yayoi Kusama, Barbara Kruger, Damien Hirst, Gavin Turk,[25] Jake and Dinos Chapman, Tim Noble and Sue Webster,[26] Rachel Whiteread, Paul McCarthy, Tom Friedman,[27] and Tracey Emin have also either designed chess sets or made works that reference the game.[28][29]

In literature

Poems

- Versus de scachis (c. 997), earliest known reference to chess in a European text

- Scachs d'amor (Catalan: Chess of Love) (late 15th century). Describes a game between Mars and Venus

- De ludo scachorum (On the Game of Chess) (early 16th century) by Francesco Bernardino Caldogno. A collection of chess gameplay advice in poetic form

- Scaccia ludus (1527) by Marco Girolamo Vida. The poem describes a game of chess played by Apollo and Mercury on Mount Olympus

- Chess (c. 1565) by Jan Kochanowski. An epos parody which portrays a game of chess as a battle between two armies

- Caissa, or the game of chess (1772) by William Jones. Inspired by ancient Greek mythology, the poem tells the story of dryad Caissa, with whom Mars falls in love. In an attempt to win her heart, Mars asks the god of sport to create a gift for Caissa. The god creates the game of chess

- A Game of Chess, a section in The Waste Land (1922) by T. S. Eliot

- The Game of Chess included in Dreamtigers (1960), a poem (two sonnets) by Jorge Luis Borges

Novels

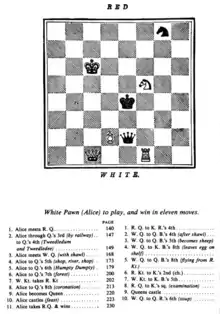

- Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871) by Lewis Carroll. The book is chess-themed. Most main characters in the story are represented as chess pieces, with the main protagonist, Alice, being a pawn

- The Twelve Chairs (1928) by Ilf and Petrov, partially taking place at a chess club

- The Defense (1930) by Vladimir Nabokov. The main character, Aleksandr Luzhin, suffers from mental problems because of his obsession with chess

- The Royal Game (1942), a novella by Stefan Zweig

- All the King's Horses (1951) by Kurt Vonnegut, also included in Welcome to the Monkey House (1968)

- John and the Chess Men (1952) by Helen Weissenstein, a children's novel introducing the game of chess. The author competed in several US women's championships.

- From Russia, with Love (1957) by Ian Fleming, part of the James Bond series. One of the villains, Tov Kronsteen, is a chess grand master who applies chess principles to espionage

- The Chess Players (1960) by Frances Parkinson Keyes, a fictionalized account of the life of Paul Morphy.

- Forbidden Planet (1961) by Lionel Fanthorpe using the pseudonym John E. Muller, which describes an interstellar chess game played by superhuman entities using humans as pawns.

- The Squares of the City (1965), a science fiction novel by John Brunner, structured after the famous 1892 chess game between Wilhelm Steinitz and Mikhail Chigorin.

- Invisible Cities (1972) by Italo Calvino

- The Westing Game (1978) by Ellen Raskin

- Szachista (Polish: The Chess Player) (1980) by Waldemar Łysiak, centered on the game of chess between Napoleon Bonaparte and The Turk

- The Queen's Gambit (1983) by Walter Tevis.

- The Tower Struck By Lightning (1983) by Fernando Arrabal

- The Discworld series (since 1983) by Terry Pratchett features a chess variant called Stealth Chess, which adds an assassin piece to the game. It is described in The Discworld Companion (1994)

- Unsound Variations (1987), a novella by George R. R. Martin included in Portraits of His Children

- The Eight (1988) by Katherine Neville. The main character, Catherine Velis, tries to recover the pieces of a chess set once owned by Charlemagne[9]

- The Joy Luck Club (1989) by Amy Tan

- The Flanders Panel (1990) by Arturo Pérez-Reverte, a chess-themed crime novel

- The Lüneberg Variation (1993) by Paolo Maurensig

- Harry Potter series (1997–2007) by J. K. Rowling. The series fictional universe features wizard's chess, a chess variant where the pieces are similar to living beings, to which the players give orders by voice

- Lord Loss (2005) by Darren Shan. The main character, Grubbs Grady, lives in a family of chess players

- Dissident Gardens (2013) by Jonathan Lethem. Uncle Lenny, who once played Bobby Fischer to a draw as a participant in a simultaneous exhibition in which Fischer defeated everyone else, destroys the chess confidence and ambitions of the young Cicero.

- Zugzwang (2006) by Ronan Bennett. St Petersburg tournament 1914. Chess, psychoanalysis, murder, intrigue, terrorism.

- Alekhine's Diagonal (2021) by Arthur Larrue. A fictionalized account of the life of the chess champion of the world Alexandre Alekhine and especially his compromission with the Nazi regime during World War II.

Short stories

- Striding Folly (1939) by Dorothy L. Sayers

- The Immortal Game (1954) by Poul Anderson, inspired by the 1851 game played by Adolf Anderssen and Lionel Kieseritzky

- Quarantine (1977), a short story by Arthur C. Clarke, about an extraterrestrial civilization which discovers chess after visiting Earth[30]

- Unicorn Variation (1983) by Roger Zelazny, included in Unicorn Variations

Comics

- Superman: Red Son (2003)

Plays

- The Tempest (1610) by William Shakespeare

- A Game at Chess (1624) by Thomas Middleton

- Endgame (1957) by Samuel Beckett

- Der Seekadett (known in English as The Royal Middy and in Italian as Lo Scacchiere della Regina) (1876) by Richard Genée, the name borrows from Seekadettenmatt.[31]

In film and television

Feature films, short films and made-for-TV films

- A Chess Dispute (1903), a one-minute comedy by British film pioneer Robert W. Paul. Earliest known film with a chess theme.

- Entr'acte (1924), a short Dadaist film by René Clair

- Chess Fever (1925), a short Soviet comedy film featuring a cameo appearance by José Raúl Capablanca.

- Casablanca (1942), the character Rick Blaine, played by Humphrey Bogart, analyzes a game. (Bogart was also an avid chess player in real life.)[32]

- The Seventh Seal (1957), centered on a game of chess between a medieval knight and the personification of Death

- Donald Duck in Mathmagic Land (1959), featuring Donald Duck on the chess game board based on the book by Lewis Carroll's Through The Looking Glass

- No Name on the Bullet (1959), a Western movie with chess scenes that symbolize how the main characters are trying to outsmart each other

- From Russia with Love (1963), based on the Ian Fleming novel of the same name, as mentioned above

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), features a game of chess played between the HAL 9000 computer an astronaut, Frank Poole

- Grossmeister (1972), Soviet film about the rise of a young grandmaster

- The Chess Players (1977), one of the subplots tells the story of two men obsessed with shatranj

- Black and White Like Day and Night (1978), German Television film directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Bruno Ganz as a deranged chess player challenging the Soviet World Champion

- Mystery of Chessboxing (1979)

- Blade Runner (1982), the replicant Roy Batty and his creator Eldon Tyrell play a game of chess (based on the Immortal Game)

- Dangerous Moves (1984), about two men competing in the World Chess Championship Games

- The Great Mouse Detective (1986), featuring Basil of Baker Street, Dr. David Q. Dawson, and Olivia Flaversham are looking for her father who was kidnapped by Professor Ratigan and Fidget looking at them walking through the chess game board inside the toy store in London, England

- Mighty Pawns (1987)

- Knight Moves (1992), about a chess grandmaster who is accused of several murders

- Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993), based on the life of Joshua Waitzkin

- Fresh (1994)

- The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

- Independence Day (1996), features one of the main characters, David Levinson, playing chess with his father in New York City; later, David realizes that the aliens have set their ships across the world like that in chess and plan to attack

- Geri's Game (1997), an animated short film about an old man named Geri who adopts two personalities to play chess with himself

- The Luzhin Defence (2000), based on the Nabokov's book The Defense mentioned above

- X-Men (2000), X-Men: The Last Stand (2006), X-Men: First Class (2011), and X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014) Charles Xavier and Magneto both have a passion for chess and play it in many of their scenes together.

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001), the sorcerer's stone, has magical chess game

- The Chronicles of Riddick (2004) briefly features prison guards playing chess against mercenaries, using live ammunition for pieces

- Knights of the South Bronx (2005), about a teacher who helps students at a tough inner-city school to succeed by teaching them to play chess

- Revolver (2005)

- Queen to Play (2009)

- Bobby Fischer Against the World (2011), an HBO original documentary directed by Liz Garbus premiered on June 6, 2011; explores the complex life of Fischer.[33]

- Life of a King (2013), an ex-con teaches chess to inner city high school kids

- The Dark Horse (2014), about a bipolar man who helps at-risk youth by teaching them chess

- Pawn Sacrifice (2014), a dramatised account of Bobby Fischer's 1972 match with Boris Spassky

- Wicked Blood (2014), about a teenage girl trying to escape a criminal family, with a chess poem interwoven among the plot shifts – one of her uncle's was once the state champ

- Chess Poem (2016), a short film adaptation of J.L. Borges poem "Ajedrez." Narrated in Chinese, features Wei Yi "immortal game"

- Lou (2022), Lou, the title character, mentions that her son once beat her in chess at only 5 years old. Later in the film we see a flashback to the game in question.

Television series

- Noggin the Nog (1959–1965). The characters' design is inspired by the Lewis chessmen.[34]

- Star Trek (since 1966), several episodes feature a Tri-Dimensional chess variant

- Mission: Impossible (1966–1973) one episode "A Game of Chess", season 2, episode 17, features cheating in a chess tournament by using a computer.

- The Prisoner (1967–1968) one episode ("Checkmate") features outdoor chess using people as pieces

- Land of the Giants (1968–1970). The season two episode "Deadly Pawn" features the castaways as chess pieces in a game for their lives.

- Columbo, in the episode "The Most Dangerous Match" (1973), has Lt. Columbo match wits with a murderous chessmaster.

- Doctor Who, in the episode The Curse of Fenric (1989), features chess as a theme, both the physical game and as a metaphor for the events of the story.

- Twin Peaks (1990–1991) in episode 2017, the characters Pete Martell and Dale Cooper discuss chess moves. A chess board diagram highlighting the Capablanca-Marshall game from 1909 covers a painting of a tree on the background wall.

- The X-Files series, in "The End" episode (1998)

- The West Wing (1999–2006), in the episode "Hartsfield's Landing" (2002)[35]

- Last Exile (2003), an anime series. All the episodes are named after chess-related terms (see the list of episodes)

- Code Geass (2006–2007), an anime series

- House, in the episode "The Jerk" (2007), about a prodigy with behavioral problems

- Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles (2008–2009) – the origin of the Skynet organization is a computer chess program; chess tournament is featured in season one episodes

- Law and Order: Special Victims Unit series, in the "Hothouse" episode of season ten (2009), in which a young genius is seen obsessing over a chess game

- The Wire (2002–2008), Dee uses the game of chess to explain the drug trade to Bodie and Wallace.

- Endgame (TV series), (2011) Canadian television series that follows former World Chess Champion Arkady Balagan who uses his analytical skills to solve crimes

- Doctor Who serial, in the 2013 episode Nightmare in Silver, Doctor Who plays chess against the Cyberiad, the collective consciousness of all Cybermen

- The Queen's Gambit, a 2020 Netflix adaptation of the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, starring Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon, a chess prodigy.

In painting

As the popularity of the game became widespread during the 15th and 16th centuries, so too did the number of paintings depicting the subject.[36] Continuing into the 20th century, artists created works related to the game often taking inspiration from the life of famous players or well-known games. An unusual connection between art and chess is the life of Marcel Duchamp, who in 1923 almost fully suspended his artistic career to focus on chess.[37][38][39]

- I Giocatori di Scacchi (The Chess Players) (c. 1590) by Ludovico Carracci

- Arabes jouant aux échecs (Arabs Playing Chess) (1847) by Eugène Delacroix

- Les Joueurs d'échecs (The Chess Players) (1863) by Honoré Daumier

- The Chess Players (1876) by Thomas Eakins

- The Veterans (1886) by Richard Creifelds

- La famille du peintre (1911) by Henri Matisse

- Portrait de joueurs d'echecs (Portrait of Chess Players) (1911) by Marcel Duchamp

- Femme à côté d'un échiquier (1928) by Henri Matisse

- Super Chess (1937) by Paul Klee

- A lot of paintings by Samuel Bak

Moors from Andalusia playing chess, Book of Games by King Alfonso X, 1283

Moors from Andalusia playing chess, Book of Games by King Alfonso X, 1283 Niccolò di Pietro, 1413–15, The Conversion of Saint Augustin, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

Niccolò di Pietro, 1413–15, The Conversion of Saint Augustin, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

Liberale da Verona, The Chess Players, c. 1475 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Liberale da Verona, The Chess Players, c. 1475 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Paris Bordone, c. 1545, Chess players, oil on canvas, Mailand, Wohnhaus

Paris Bordone, c. 1545, Chess players, oil on canvas, Mailand, Wohnhaus Antonis Mor, 1549, Von Sachsen vs. a Spaniard

Antonis Mor, 1549, Von Sachsen vs. a Spaniard Hans Muelich, 1552, Duke Albrecht V. of Bavaria and his wife Anna of Austria playing chess

Hans Muelich, 1552, Duke Albrecht V. of Bavaria and his wife Anna of Austria playing chess Karel van Mander, 1600 (attributed to), Les joueurs d'échecs

Karel van Mander, 1600 (attributed to), Les joueurs d'échecs Edward Harrison May, 1867, Lady Howe mating Benjamin Franklin

Edward Harrison May, 1867, Lady Howe mating Benjamin Franklin

Honoré Daumier, 1863, The Chess Players

Honoré Daumier, 1863, The Chess Players Thomas Eakins, 1876, The Chess Players

Thomas Eakins, 1876, The Chess Players Richard Creifelds, c. 1886, The Veterans, Brooklyn Museum

Richard Creifelds, c. 1886, The Veterans, Brooklyn Museum.jpg.webp) John Lavery, 1929, The Chess Players

John Lavery, 1929, The Chess Players

%252C_detail_chessboard_and_table.jpg.webp)

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_92.1_x_73_cm%252C_Art_Institute_of_Chicago_(detail).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In video games

- Parasite Eve II (2000) features GOLEMs, villainous genetically enhanced cyborg super soldiers that are divided into different types named after chess pieces: Pawn GOLEMs, Rook GOLEMs, Knight GOLEMs, and Bishop GOLEMs, plus a unique leader known as No. 9 (King GOLEM).

- Killer7 (2005)

- Deadly Premonition (2010)

- Baba Is You (2019) features the objects Pawn and Knight in its level editor.

In music

.jpg.webp)

- Checkmate, a ballet by the composer Arthur Bliss

- In 1968, the composer John Cage and artist Marcel Duchamp appeared together at a concert entitled Reunion, playing a game of chess and composing Aleatoric music by triggering a series of photoelectric cells underneath the chessboard.[40]

- Chess, a musical by Tim Rice and Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson of ABBA

- The game is referenced in Wu-Tang Clan songs such as "Da Mystery of Chessboxin'". "I love the game of chess", explained founder RZA. "The person who taught me chess was the girl who took my virginity. She was pretty good at chess and the pussy was even better. Now I take that shit seriously. I hate losing."[41] In 2005 Wu-Tang Clan member GZA released an album entitled Grandmasters in which every track had a chess theme.

- Songwriter, musician, and Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan is a chess player.

See also

References

- Litmanowicz (1974), p. 13

- Gamer, Helena M. (1954). "The Earliest Evidence of Chess in Western Literature: The Einsiedeln Verses". Speculum. 29 (4): 734–750. doi:10.2307/2847098. JSTOR 2847098. S2CID 162079385.

- Sonja Musser Golladay (2007). "Los Libros de Acedrex Dados E Tablas: Historical, Artistic and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X's Book of Games". University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- The Immortal Game: A History of Chess

- Raymond Keene (10 March 2008). "Renaissance chess master and the Da Vinci decode mystery". The Times. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- "Experts link Leonardo da Vinci to chess puzzles in Renaissance treatise". Winnipeg Free Press. 14 March 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Litmanowicz (1974), p. 11

- Litmanowicz (1974), p. 12

- "Elenco romanzi e racconti sul gioco degli scacchi" [List of novels and short stories on chess]. Terni Scacchi (in Italian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- Litmanowicz (1974), p. 14

- Roesch vs Willi Schlage (1910) in chessgames.com

- Tim Krabbé. "Open chess diary 1–20 (entry 3)". Tim Krabbé's blog. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Harold C. Schonberg (8 May 1998). "Does Anyone Make a Bad Move In 'Chess'?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- Marcadé, Bernard (2007). "XIX CHESS MANIAQUE A BUENOS AIRES". Marcel Duchamp : la vie à crédit : biographie (in French). [Paris]: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-068226-0. OCLC 319214976.

- "Dont forget. Marcel Duchamp. A game of chess with Man Ray and Dalí". Murcia Today. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Dalí, Salvador. "Echecs (Hommage à Marcel Duchamp)". Christie's. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- "Imagery of chess exhibition brochure, Duchamp Research Portal". www.duchamparchives.org. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- "The Chess Game". philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- "Portrait of Chess Players". philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Castle, Jack (2020-03-31). "'Finding the right move': Marcel Duchamp and his passion for chess". Christie's. Retrieved 2022-12-14.

- "René Clair. Entr'acte. 1924 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- Oisteanu, Valery (2009-11-05). "Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Picasso, Pablo. "Chess, Paris, autumn 1911". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Gris, Juan. "Chessboard, Glass, and Dish". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- Turk, Gavin. "The Mechanical Turk". Christie's. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- "Tim Noble & Sue Webster – DeadAlive, 2012". www.timnobleandsuewebster.com. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- "Yayoi Kusama, Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Paul McCarthy and Tom Friedman star in The Art of Chess | art | Agenda | Phaidon". www.phaidon.com. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- "7 Chess Sets Designed by Famous Artists". Widewalls. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- "Checkmates: how artists fell in love with chess". the Guardian. 2012-09-06. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- Arthur C. Clarke. "Quarantine". IBM. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- Dario Salvi (2017). Richard Genée's The Royal Middy (Der Seekadett). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781527505292.

- Bell, Steve; Gorce, Tammy La (2016-12-02). "Which Famous Actor Hustled Chess Games in New York City?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- hbo.com

- "The Saga of Noggin the Nog". BFI Screenonline. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Heisler, Steve (15 August 2011). "The West Wing: "Hartsfield's Landing"". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- Władysław Litmanowicz, Dykteryjki i ciekawostki szachowe (Chess trivia and anecdotes), in Polish. Warsaw: Sport i Turystyka. 1974, pp. 11–27

- "Marcel Duchamp." Kynaston McShine.1989.

- ""Becoming Duchamp" by Sylvère Lotringer". Toutfait.com. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- Brady, Frank: Bobby Fischer: profile of a prodigy, Courier Dover Publications, 1989; p. 207.

- ""Becoming Duchamp" by Sylvère Lotringer". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Wilkinson, Roy (July 1997). "One of these men is God". Select: 60.

Further reading

- Raabenstein, Peter (2020). Chess In Art. Prague: HereLove. ISBN 978-8090577657.

- Divinsky, Nathan (1990). The Batsford Encyclopedia of Chess. London: Batsford. ISBN 0713462140.

- Fox, Mike; James, Richard (1994). The Even More Complete Chess Addict. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0571170404.

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Litmanowicz, Władysław (1974). Dykteryjki i ciekawostki szachowe [Chess trivia and anecdotes] (in Polish). Warsaw: Sport i Turystyka. pp. 11–27.

- Griffin, Jonathan (2014). The Twenty First Century Art Book. Paul Harper, David Trigg, Eliza Williams. London. ISBN 978-0-7148-6739-7. OCLC 889547304.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Chess In Art (Streatham and Brixton Chess Club)

- McClain, Dylan (May 22, 2009). "Chess on Film". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- "Elenco romanzi e racconti sul gioco degli scacchi" [List of novels and short stories on chess]. Terni Scacchi (in Italian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- “Chess in Fiction” by Edward Winter

- Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art