Ancient Greek art

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

Greek architecture, technically very simple, established a harmonious style with numerous detailed conventions that were largely adopted by Roman architecture and are still followed in some modern buildings. It used a vocabulary of ornament that was shared with pottery, metalwork and other media, and had an enormous influence on Eurasian art, especially after Buddhism carried it beyond the expanded Greek world created by Alexander the Great. The social context of Greek art included radical political developments and a great increase in prosperity; the equally impressive Greek achievements in philosophy, literature and other fields are well known.

The earliest art by Greeks is generally excluded from "ancient Greek art", and instead known as Greek Neolithic art followed by Aegean art; the latter includes Cycladic art and the art of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures from the Greek Bronze Age.[1] The art of ancient Greece is usually divided stylistically into four periods: the Geometric, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic. The Geometric age is usually dated from about 1000 BC, although in reality little is known about art in Greece during the preceding 200 years, traditionally known as the Greek Dark Ages. The 7th century BC witnessed the slow development of the Archaic style as exemplified by the black-figure style of vase painting. Around 500 BC, shortly before the onset of the Persian Wars (480 BC to 448 BC), is usually taken as the dividing line between the Archaic and the Classical periods, and the reign of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC) is taken as separating the Classical from the Hellenistic periods. From some point in the 1st century BC onwards "Greco-Roman" is used, or more local terms for the Eastern Greek world.[2]

In reality, there was no sharp transition from one period to another. Forms of art developed at different speeds in different parts of the Greek world, and as in any age some artists worked in more innovative styles than others. Strong local traditions, and the requirements of local cults, enable historians to locate the origins even of works of art found far from their place of origin. Greek art of various kinds was widely exported. The whole period saw a generally steady increase in prosperity and trading links within the Greek world and with neighbouring cultures.

The survival rate of Greek art differs starkly between media. We have huge quantities of pottery and coins, much stone sculpture, though even more Roman copies, and a few large bronze sculptures. Almost entirely missing are painting, fine metal vessels, and anything in perishable materials including wood. The stone shell of a number of temples and theatres has survived, but little of their extensive decoration.[3]

Pottery

By convention, finely painted vessels of all shapes are called "vases", and there are over 100,000 significantly complete surviving pieces,[5] giving (with the inscriptions that many carry) unparalleled insights into many aspects of Greek life. Sculptural or architectural pottery, also very often painted, are referred to as terracottas, and also survive in large quantities. In much of the literature, "pottery" means only painted vessels, or "vases". Pottery was the main form of grave goods deposited in tombs, often as "funerary urns" containing the cremated ashes, and was widely exported.

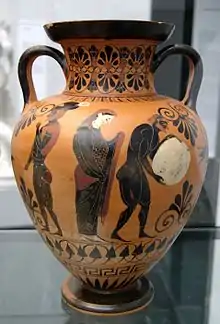

The famous and distinctive style of Greek vase-painting with figures depicted with strong outlines, with thin lines within the outlines, reached its peak from about 600 to 350 BC, and divides into the two main styles, almost reversals of each other, of black-figure and red-figure painting, the other colour forming the background in each case. Other colours were very limited, normally to small areas of white and larger ones of a different purplish-red. Within the restrictions of these techniques and other strong conventions, vase-painters achieved remarkable results, combining refinement and powerful expression. White ground technique allowed more freedom in depiction, but did not wear well and was mostly made for burial.[6]

Conventionally, the ancient Greeks are said to have made most pottery vessels for everyday use, not for display. Exceptions are the large Archaic monumental vases made as grave-markers, trophies won at games, such as the Panathenaic Amphorae filled with olive oil, and pieces made specifically to be left in graves; some perfume bottles have a money-saving bottom just below the mouth, so a small quantity makes them appear full.[7] In recent decades many scholars have questioned this, seeing much more production than was formerly thought as made to be placed in graves, as a cheaper substitute for metalware in both Greece and Etruria.[8]

Most surviving pottery consists of vessels for storing, serving or drinking liquids such as amphorae, kraters (bowls for mixing wine and water), hydria (water jars), libation bowls, oil and perfume bottles for the toilet, jugs and cups. Painted vessels for serving and eating food are much less common. Painted pottery was affordable even by ordinary people, and a piece "decently decorated with about five or six figures cost about two or three days' wages".[9] Miniatures were also produced in large numbers, mainly for use as offerings at temples.[10] In the Hellenistic period a wider range of pottery was produced, but most of it is of little artistic importance.

In earlier periods even quite small Greek cities produced pottery for their own locale. These varied widely in style and standards. Distinctive pottery that ranks as art was produced on some of the Aegean islands, in Crete, and in the wealthy Greek colonies of southern Italy and Sicily.[12] By the later Archaic and early Classical period, however, the two great commercial powers, Corinth and Athens, came to dominate. Their pottery was exported all over the Greek world, driving out the local varieties. Pots from Corinth and Athens are found as far afield as Spain and Ukraine, and are so common in Italy that they were first collected in the 18th century as "Etruscan vases".[13] Many of these pots are mass-produced products of low quality. In fact, by the 5th century BC, pottery had become an industry and pottery painting ceased to be an important art form.

The range of colours which could be used on pots was restricted by the technology of firing: black, white, red, and yellow were the most common. In the three earlier periods, the pots were left their natural light colour, and were decorated with slip that turned black in the kiln.[6]

Greek pottery is frequently signed, sometimes by the potter or the master of the pottery, but only occasionally by the painter. Hundreds of painters are, however, identifiable by their artistic personalities: where their signatures have not survived they are named for their subject choices, as "the Achilles Painter", by the potter they worked for, such as the Late Archaic "Kleophrades Painter", or even by their modern locations, such as the Late Archaic "Berlin Painter".[14]

History

The history of ancient Greek pottery is divided stylistically into five periods:

- the Protogeometric from about 1050 BC

- the Geometric from about 900 BC

- the Late Geometric or Archaic from about 750 BC

- the Black Figure from the early 7th century BC

- and the Red Figure from about 530 BC

During the Protogeometric and Geometric periods, Greek pottery was decorated with abstract designs, in the former usually elegant and large, with plenty of unpainted space, but in the Geometric often densely covering most of the surface, as in the large pots by the Dipylon Master, who worked around 750. He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. These often represent funeral processions, or battles, presumably representing those fought by the deceased.[15]

The Geometric phase was followed by an Orientalizing period in the late 8th century, when a few animals, many either mythical or not native to Greece (like the sphinx and lion respectively) were adapted from the Near East, accompanied by decorative motifs, such as the lotus and palmette. These were shown much larger than the previous figures. The Wild Goat Style is a regional variant, very often showing goats. Human figures were not so influenced from the East, but also became larger and more detailed.[16]

The fully mature black-figure technique, with added red and white details and incising for outlines and details, originated in Corinth during the early 7th century BC and was introduced into Attica about a generation later; it flourished until the end of the 6th century BC.[17] The red-figure technique, invented in about 530 BC, reversed this tradition, with the pots being painted black and the figures painted in red. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Sometimes larger vessels were engraved as well as painted. Erotic themes, both heterosexual and male homosexual, became common.[18]

By about 320 BC fine figurative vase-painting had ceased in Athens and other Greek centres, with the polychromatic Kerch style a final flourish; it was probably replaced by metalwork for most of its functions. West Slope Ware, with decorative motifs on a black glazed body, continued for over a century after.[19] Italian red-figure painting ended by about 300, and in the next century the relatively primitive Hadra vases, probably from Crete, Centuripe ware from Sicily, and Panathenaic amphorae, now a frozen tradition, were the only large painted vases still made.[20]

Late Geometric pyxis, British Museum

Late Geometric pyxis, British Museum Corinthian orientalising jug, c. 620 BC, Antikensammlungen Munich

Corinthian orientalising jug, c. 620 BC, Antikensammlungen Munich Black-figure olpe (wine vessel) by the Amasis Painter, depicting Heracles and Athena, c. 540 BC, Louvre

Black-figure olpe (wine vessel) by the Amasis Painter, depicting Heracles and Athena, c. 540 BC, Louvre

Hellenistic relief bowl with the head of a maenad, 2nd century BC (?), British Museum

Hellenistic relief bowl with the head of a maenad, 2nd century BC (?), British Museum

Metalwork

.jpg.webp)

Fine metalwork was an important art in ancient Greece, but later production is very poorly represented by survivals, most of which come from the edges of the Greek world or beyond, from as far as France or Russia. Vessels and jewellery were produced to high standards, and exported far afield. Objects in silver, at the time worth more relative to gold than it is in modern times, were often inscribed by the maker with their weight, as they were treated largely as stores of value, and likely to be sold or re-melted before very long.[22]

During the Geometric and Archaic phases, the production of large metal vessels was an important expression of Greek creativity, and an important stage in the development of bronzeworking techniques, such as casting and repousse hammering. Early sanctuaries, especially Olympia, yielded many hundreds of tripod-bowl or sacrificial tripod vessels, mostly in bronze, deposited as votives. These had a shallow bowl with two handles raised high on three legs; in later versions the stand and bowl were different pieces. During the Orientalising period, such tripods were frequently decorated with figural protomes, in the shape of griffins, sphinxes and other fantastic creatures.[23]

Swords, the Greek helmet and often body armour such as the muscle cuirass were made of bronze, sometimes decorated in precious metal, as in the 3rd-century Ksour Essef cuirass.[24] Armour and "shield-bands" are two of the contexts for strips of Archaic low relief scenes, which were also attached to various objects in wood; the band on the Vix Krater is a large example.[25] Polished bronze mirrors, initially with decorated backs and kore handles, were another common item; the later "folding mirror" type had hinged cover pieces, often decorated with a relief scene, typically erotic.[26] Coins are described below.

From the late Archaic the best metalworking kept pace with stylistic developments in sculpture and the other arts, and Phidias is among the sculptors known to have practiced it.[27] Hellenistic taste encouraged highly intricate displays of technical virtuousity, tending to "cleverness, whimsy, or excessive elegance".[28] Many or most Greek pottery shapes were taken from shapes first used in metal, and in recent decades there has been an increasing view that much of the finest vase-painting reused designs by silversmiths for vessels with engraving and sections plated in a different metal, working from drawn designs.[29]

Exceptional survivals of what may have been a relatively common class of large bronze vessels are two volute kraters, for mixing wine and water.[30] These are the Vix Krater, c. 530 BC, 1.63m (5'4") high and over 200 kg (450 lbs) in weight, holding some 1,100 litres, and found in the burial of a Celtic woman in modern France,[31] and the 4th-century Derveni Krater, 90.5 cm (35 in.) high.[32] The elites of other neighbours of the Greeks, such as the Thracians and Scythians, were keen consumers of Greek metalwork, and probably served by Greek goldsmiths settled in their territories, who adapted their products to suit local taste and functions. Such hybrid pieces form a large part of survivals, including the Panagyurishte Treasure, Borovo Treasure, and other Thracian treasures, and several Scythian burials, which probably contained work by Greek artists based in the Greek settlements on the Black Sea.[33] As with other luxury arts, the Macedonian royal cemetery at Vergina has produced objects of top quality from the cusp of the Classical and Hellenistic periods.[34]

Jewellery for the Greek market is often of superb quality,[35] with one unusual form being intricate and very delicate gold wreaths imitating plant-forms, worn on the head. These were probably rarely, if ever, worn in life, but were given as votives and worn in death.[36] Many of the Fayum mummy portraits wear them. Some pieces, especially in the Hellenistic period, are large enough to offer scope for figures, as did the Scythian taste for relatively substantial pieces in gold.[37]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Vix Krater, a late Archaic monumental bronze vessel, exported to French Celts

The Vix Krater, a late Archaic monumental bronze vessel, exported to French Celts Fancy Early Classical bronze mirror with human caryatid handle, c. 460 BC

Fancy Early Classical bronze mirror with human caryatid handle, c. 460 BC Golden wreath, 370-360, from southern Italy

Golden wreath, 370-360, from southern Italy

4th century BC Greek gold and bronze rhyton with head of Dionysus, Tamoikin Art Fund

4th century BC Greek gold and bronze rhyton with head of Dionysus, Tamoikin Art Fund Fragment of a gold wreath, c. 320-300 BC, from a burial in Crimea

Fragment of a gold wreath, c. 320-300 BC, from a burial in Crimea Gold hair ornament and net, 3rd century BC

Gold hair ornament and net, 3rd century BC%252C_medaglioni_ellenistici_in_argento%252C_II-I_sec_ac._02.JPG.webp) Late Hellenistic silver medallion

Late Hellenistic silver medallion

Monumental sculpture

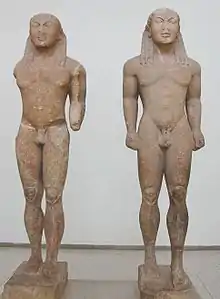

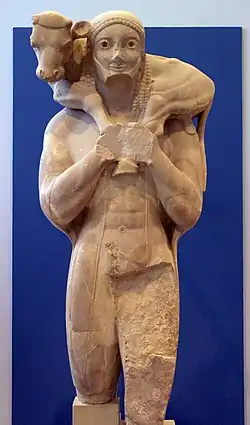

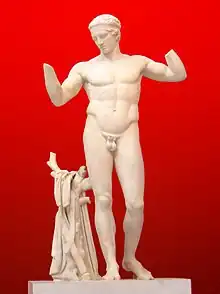

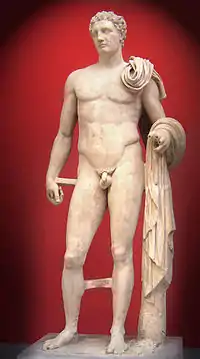

The Greeks decided very early on that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavour.[39] Seeing their gods as having human form, there was little distinction between the sacred and the secular in art—the human body was both secular and sacred. A male nude of Apollo or Heracles had only slight differences in treatment to one of that year's Olympic boxing champion. In the Archaic Period the most important sculptural form was the kouros (plural kouroi), the standing male nude (See for example Biton and Kleobis). The kore (plural korai), or standing clothed female figure, was also common, but since Greek society did not permit the public display of female nudity until the 4th century BC, the kore is considered to be of less importance in the development of sculpture.[40] By the end of the period architectural sculpture on temples was becoming important.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce monumental sculpture merely for artistic display. Statues were commissioned either by aristocratic individuals or by the state, and used for public memorials, as offerings to temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is frequently shown by inscriptions on the statues), or as markers for graves. Statues in the Archaic period were not all intended to represent specific individuals. They were depictions of an ideal—beauty, piety, honor or sacrifice. These were always depictions of young men, ranging in age from adolescence to early maturity, even when placed on the graves of (presumably) elderly citizens. Kouroi were all stylistically similar. Graduations in the social stature of the person commissioning the statue were indicated by size rather than artistic innovations.[41]

Unlike authors, those who practiced the visual arts, including sculpture, initially had a low social status in ancient Greece, though increasingly leading sculptors might become famous and rather wealthy, and often signed their work (often on the plinth, which typically became separated from the statue itself).[42] Plutarch (Life of Pericles, II) said "we admire the work of art but despise the maker of it"; this was a common view in the ancient world. Ancient Greek sculpture is categorised by the usual stylistic periods of "Archaic", "Classical" and "Hellenistic", augmented with some extra ones mainly applying to sculpture, such as the Orientalizing Daedalic style and the Severe style of early Classical sculpture.[43]

Materials, forms

Surviving ancient Greek sculptures were mostly made of two types of material. Stone, especially marble or other high-quality limestones was used most frequently and carved by hand with metal tools. Stone sculptures could be free-standing fully carved in the round (statues), or only partially carved reliefs still attached to a background plaque, for example in architectural friezes or grave stelai.[44]

Bronze statues were of higher status, but have survived in far smaller numbers, due to the reusability of metals. They were usually made in the lost wax technique. Chryselephantine, or gold-and-ivory, statues were the cult-images in temples and were regarded as the highest form of sculpture, but only some fragmentary pieces have survived. They were normally over-lifesize, built around a wooden frame, with thin carved slabs of ivory representing the flesh, and sheets of gold leaf, probably over wood, representing the garments, armour, hair, and other details.[45]

In some cases, glass paste, glass, and precious and semi-precious stones were used for detail such as eyes, jewellery, and weaponry. Other large acrolithic statues used stone for the flesh parts, and wood for the rest, and marble statues sometimes had stucco hairstyles. Most sculpture was painted (see below), and much wore real jewellery and had inlaid eyes and other elements in different materials.[46]

Terracotta was occasionally employed, for large statuary. Few examples of this survived, at least partially due to the fragility of such statues. The best known exception to this is a statue of Zeus carrying Ganymede found at Olympia, executed around 470 BC. In this case, the terracotta is painted. There were undoubtedly sculptures purely in wood, which may have been very important in early periods, but effectively none have survived.[47]

Archaic

Bronze Age Cycladic art, to about 1100 BC, had already shown an unusual focus on the human figure, usually shown in a straightforward frontal standing position with arms folded across the stomach. Among the smaller features only noses, sometimes eyes, and female breasts were carved, though the figures were apparently usually painted and may have originally looked very different.

Inspired by the monumental stone sculpture of Egypt and Mesopotamia, during the Archaic period the Greeks began again to carve in stone: Greek mercenaries and merchants were active abroad, as in Egypt in the service of Pharaoh Psamtik I (664–610 BC), and were exposed to the monumental art of these countries.[48][49] It is generally agreed that "Egyptian statuary of the 2nd millennium BC gave the decisive impulse for the innovation of Greek sculpture in life-size and in hyper formats in the Archaic Period during the late 7th century."[48] Free-standing figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of Eastern models, but their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture, as for example the Lady of Auxerre and Torso of Hera (Early Archaic period, c. 660–580 BC, both in the Louvre, Paris). After about 575 BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. This expression, which has no specific appropriateness to the person or situation depicted, may have been a device to give the figures a distinctive human characteristic.[50]

Three types of figures were used—the standing nude youth (kouros), the standing draped girl (kore) and, less frequently, the seated woman.[51] All emphasize and generalize the essential features of the human figure and show an increasingly accurate comprehension of human anatomy. The youths were either sepulchral or votive statues. Examples are Apollo (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), an early work; the Strangford Apollo from Anafi (British Museum, London), a much later work; and the Anavyssos Kouros (National Archaeological Museum of Athens). More of the musculature and skeletal structure is visible in this statue than in earlier works. The standing, draped girls have a wide range of expression, as in the sculptures in the Acropolis Museum of Athens. Their drapery is carved and painted with the delicacy and meticulousness common in the details of sculpture of this period.[52]

Archaic reliefs have survived from many tombs, and from larger buildings at Foce del Sele (now in the museum at Paestum) in Italy, with two groups of metope panels, from about 550 and 510, and the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi, with friezes and a small pediment. Parts, all now in local museums, survive of the large triangular pediment groups from the Temple of Artemis, Corfu (c. 580), dominated by a huge Gorgon, and the Old Temple of Athena in Athens (c. 530-500).[53]

Dipylon Kouros, c. 600 BC, Athens, Kerameikos Museum

Dipylon Kouros, c. 600 BC, Athens, Kerameikos Museum

Frieze of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi, depicting a Gigantomachy, c. 525 BC, Delphi Archaeological Museum

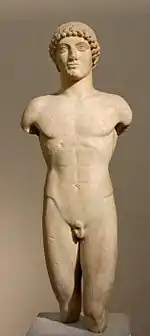

Frieze of the Siphnian Treasury, Delphi, depicting a Gigantomachy, c. 525 BC, Delphi Archaeological Museum The Strangford Apollo, 500-490, one of the last kouroi

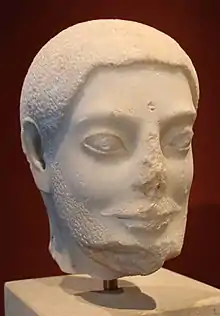

The Strangford Apollo, 500-490, one of the last kouroi The Sabouroff head, an important example of Late Archaic Greek marble sculpture, c. 550-525 BCE.

The Sabouroff head, an important example of Late Archaic Greek marble sculpture, c. 550-525 BCE. The Perserschutt, or "Persian rubble", dating from the destruction of Athens in 480/479 BC during the Second Persian invasion of Greece offer a clear datation marker for Archaic statuary.

The Perserschutt, or "Persian rubble", dating from the destruction of Athens in 480/479 BC during the Second Persian invasion of Greece offer a clear datation marker for Archaic statuary.

Classical

In the Classical period there was a revolution in Greek statuary, usually associated with the introduction of democracy and the end of the aristocratic culture associated with the kouroi. The Classical period saw changes in the style and function of sculpture. Poses became more naturalistic (see the Charioteer of Delphi for an example of the transition to more naturalistic sculpture), and the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting the human form in a variety of poses greatly increased. From about 500 BC statues began to depict real people. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton set up in Athens to mark the overthrow of the tyranny were said to be the first public monuments to actual people.[54]

At the same time sculpture and statues were put to wider uses. The great temples of the Classical era such as the Parthenon in Athens, and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, required relief sculpture for decorative friezes, and sculpture in the round to fill the triangular fields of the pediments. The difficult aesthetic and technical challenge stimulated much in the way of sculptural innovation. These works survive only in fragments, the most famous of which are the Parthenon Marbles, half of which are in the British Museum.[57]

Funeral statuary evolved during this period from the rigid and impersonal kouros of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical period. These monuments are commonly found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict "ideal" types—the mourning mother, the dutiful son—they increasingly depicted real people, typically showing the departed taking his dignified leave from his family. They are among the most intimate and affecting remains of the ancient Greeks.[58]

In the Classical period for the first time we know the names of individual sculptors. Phidias oversaw the design and building of the Parthenon. Praxiteles made the female nude respectable for the first time in the Late Classical period (mid-4th century): his Aphrodite of Knidos, which survives in copies, was said by Pliny to be the greatest statue in the world.[59]

The most famous works of the Classical period for contemporaries were the colossal Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Statue of Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon. Both were chryselephantine and executed by Phidias or under his direction, and are now lost, although smaller copies (in other materials) and good descriptions of both still exist. Their size and magnificence prompted emperors to seize them in the Byzantine period, and both were removed to Constantinople, where they were later destroyed in fires.[60]

The Marathon Youth, 4th-century BC bronze statue, possibly by Praxiteles, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

The Marathon Youth, 4th-century BC bronze statue, possibly by Praxiteles, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Hellenistic

The transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic period occurred during the 4th century BC. Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC), Greek culture spread as far as India, as revealed by the excavations of Ai-Khanoum in eastern Afghanistan, and the civilization of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks. Greco-Buddhist art represented a syncretism between Greek art and the visual expression of Buddhism. Thus Greek art became more diverse and more influenced by the cultures of the peoples drawn into the Greek orbit.[61]

In the view of some art historians, it also declined in quality and originality. This, however, is a judgement which artists and art-lovers of the time would not have shared. Indeed, many sculptures previously considered as classical masterpieces are now recognised as being Hellenistic. The technical ability of Hellenistic sculptors is clearly in evidence in such major works as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and the Pergamon Altar. New centres of Greek culture, particularly in sculpture, developed in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamum, and other cities, where the new monarchies were lavish patrons.[62] By the 2nd century the rising power of Rome had also absorbed much of the Greek tradition—and an increasing proportion of its products as well.[63]

During this period sculpture became more naturalistic, and also expressive; the interest in depicting extremes of emotion being sometimes pushed to extremes. Genre subjects of common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens; the Boy with Thorn is an example. Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.[64]

The world of Dionysus, a pastoral idyll populated by satyrs, maenads, nymphs and sileni, had been often depicted in earlier vase painting and figurines, but rarely in full-size sculpture. Now such works were made, surviving in copies including the Barberini Faun, the Belvedere Torso, and the Resting Satyr; the Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reflect related themes.[65] At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities springing up all over Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardisation and some lowering of quality. For these reasons many more Hellenistic statues have survived than is the case with the Classical period.

Some of the best known Hellenistic sculptures are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (2nd or 1st century BC),[66] the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos known as the Venus de Milo (mid-2nd century BC), the Dying Gaul (about 230 BC), and the monumental group Laocoön and His Sons (late 1st century BC). All these statues depict Classical themes, but their treatment is far more sensuous and emotional than the austere taste of the Classical period would have allowed or its technical skills permitted.

The multi-figure group of statues was a Hellenistic innovation, probably of the 3rd century, taking the epic battles of earlier temple pediment reliefs off their walls, and placing them as life-size groups of statues. Their style is often called "baroque", with extravagantly contorted body poses, and intense expressions in the faces. The reliefs on the Pergamon Altar are the nearest original survivals, but several well known works are believed to be Roman copies of Hellenistic originals. These include the Dying Gaul and Ludovisi Gaul, as well as a less well known Kneeling Gaul and others, all believed to copy Pergamene commissions by Attalus I to commemorate his victory around 241 over the Gauls of Galatia, probably comprising two groups.[67]

The Laocoön Group, the Farnese Bull, Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus ("Pasquino group"), Arrotino, and the Sperlonga sculptures, are other examples.[68] From the 2nd century the Neo-Attic or Neo-Classical style is seen by different scholars as either a reaction to baroque excesses, returning to a version of Classical style, or as a continuation of the traditional style for cult statues.[69] Workshops in the style became mainly producers of copies for the Roman market, which preferred copies of Classical rather than Hellenistic pieces.[70]

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleum include a 4th-century BC, unusually sensual, detailed and feministic (as opposed to deified) depiction of Isis, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms beginning around the time of Egypt's conquest by Alexander the Great. However this was untypical of Ptolemaic court sculpture, which generally avoided mixing Egyptian styles with its fairly conventional Hellenistic style,[71] while temples in the rest of the country continued using late versions of traditional Egyptian formulae.[72] Scholars have proposed an "Alexandrian style" in Hellenistic sculpture, but there is in fact little to connect it with Alexandria.[73]

Hellenistic sculpture was also marked by an increase in scale, which culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), which was the same size as the Statue of Liberty. The combined effect of earthquakes and looting have destroyed this as well as other very large works of this period.

The Hellenistic Prince, a bronze statue originally thought to be a Seleucid, or Attalus II of Pergamon, now considered a portrait of a Roman general, made by a Greek artist working in Rome in the 2nd century BC.

The Hellenistic Prince, a bronze statue originally thought to be a Seleucid, or Attalus II of Pergamon, now considered a portrait of a Roman general, made by a Greek artist working in Rome in the 2nd century BC.

Laocoön and His Sons (Late Hellenistic), Vatican Museum

Laocoön and His Sons (Late Hellenistic), Vatican Museum Late Hellenistic bronze of a mounted jockey, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Late Hellenistic bronze of a mounted jockey, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Figurines

Terracotta figurines

Clay is a material frequently used for the making of votive statuettes or idols, even before the Minoan civilization and continuing until the Roman period. During the 8th century BC tombs in Boeotia often contain "bell idols", female statuettes with mobile legs: the head, small compared to the remainder of the body, is perched at the end of a long neck, while the body is very full, in the shape of a bell.[74] Archaic heroon tombs, for local heroes, might receive large numbers of crudely-shaped figurines, with rudimentary figuration, generally representing characters with raised arms.

By the Hellenistic period most terracotta figurines have lost their religious nature, and represent characters from everyday life. Tanagra figurines, from one of several centres of production, are mass-manufactured using moulds, and then painted after firing. Dolls, figures of fashionably-dressed ladies and of actors, some of these probably portraits, were among the new subjects, depicted with a refined style. These were cheap, and initially displayed in the home much like modern ornamental figurines, but were quite often buried with their owners. At the same time, cities like Alexandria, Smyrna or Tarsus produced an abundance of grotesque figurines, representing individuals with deformed members, eyes bulging and contorting themselves. Such figurines were also made from bronze.[75]

For painted architectural terracottas, see Architecture below.

Metal figurines

Figurines made of metal, primarily bronze, are an extremely common find at early Greek sanctuaries like Olympia, where thousands of such objects, mostly depicting animals, have been found. They are usually produced in the lost wax technique and can be considered the initial stage in the development of Greek bronze sculpture. The most common motifs during the Geometric period were horses and deer, but dogs, cattle and other animals are also depicted. Human figures occur occasionally. The production of small metal votives continued throughout Greek antiquity. In the Classical and Hellenistic periods, more elaborate bronze statuettes, closely connected with monumental sculpture, also became common. High quality examples were keenly collected by wealthy Greeks, and later Romans, but relatively few have survived.[76]

Bell Idol, 7th century BC

Bell Idol, 7th century BC 8th-century BC bronze votive horse from Olympia

8th-century BC bronze votive horse from Olympia Actor from the New Comedy, about 200 BC

Actor from the New Comedy, about 200 BC

Architecture

Architecture (meaning buildings executed to an aesthetically considered design) ceased in Greece from the end of the Mycenaean period (about 1200 BC) until the 7th century, when urban life and prosperity recovered to a point where public building could be undertaken. Since most Greek buildings in the Archaic and Early Classical periods were made of wood or mudbrick, nothing remains of them except a few ground-plans, and there are almost no written sources on early architecture or descriptions of buildings. Most of our knowledge of Greek architecture comes from the surviving buildings of the Late Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods (since ancient Roman architecture heavily used Greek styles), and from late written sources such as Vitruvius (1st century BC). This means that there is a strong bias towards temples, the most common major buildings to survive. Here the squared blocks of stone used for walls were useful for later buildings, and so often all that survives are parts of columns and metopes that were harder to recycle.[77]

For most of the period a strict stone post and lintel system of construction was used, held in place only by gravity. Corbelling was known in Mycenean Greece, and the arch was known from the 5th century at the latest, but hardly any use was made of these techniques until the Roman period.[78] Wood was only used for ceilings and roof timbers in prestigious stone buildings. The use of large terracotta roof tiles, only held in place by grooving, meant that roofs needed to have a low pitch.[79]

Until Hellenistic times only public buildings were built using the formal stone style; these included above all temples, and the smaller treasury buildings which often accompanied them, and were built at Delphi by many cities. Other building types, often not roofed, were the central agora, often with one or more colonnaded stoa around it, theatres, the gymnasium and palaestra or wrestling-school, the ekklesiasterion or bouleuterion for assemblies, and the propylaea or monumental gateways.[80] Round buildings for various functions were called a tholos,[81] and the largest stone structures were often defensive city walls.

Tombs were for most of the period only made as elaborate mausolea around the edges of the Greek world, especially in Anatolia.[82] Private houses were built around a courtyard where funds allowed, and showed blank walls to the street. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. They were usually built of rubble at best, and relatively little is known about them; at least for males, much of life was spent outside them.[83] A few palaces from the Hellenistic period have been excavated.[84]

.jpg.webp)

Temples and some other buildings such as the treasuries at Delphi were planned as either a cube or, more often, a rectangle made from limestone, of which Greece has an abundance, and which was cut into large blocks and dressed. This was supplemented by columns, at least on the entrance front, and often on all sides.[85] Other buildings were more flexible in plan, and even the wealthiest houses seem to have lacked much external ornament. Marble was an expensive building material in Greece: high quality marble came only from Mt Pentelus in Attica and from a few islands such as Paros, and its transportation in large blocks was difficult. It was used mainly for sculptural decoration, not structurally, except in the very grandest buildings of the Classical period such as the Parthenon in Athens.[86]

There were two main classical orders of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic, with the Corinthian order only appearing in the Classical period, and not becoming dominant until the Roman period. The most obvious features of the three orders are the capitals of the columns, but there are significant differences in other points of design and decoration between the orders.[87] These names were used by the Greeks themselves, and reflected their belief that the styles descended from the Dorian and Ionian Greeks of the Dark Ages, but this is unlikely to be true. The Doric was the earliest, probably first appearing in stone in the earlier 7th century, having developed (though perhaps not very directly) from predecessors in wood.[88] It was used in mainland Greece and the Greek colonies in Italy. The Ionic style was first used in the cities of Ionia (now the west coast of Turkey) and some of the Aegean islands, probably beginning in the 6th century.[89] The Doric style was more formal and austere, the Ionic more relaxed and decorative. The more ornate Corinthian order was a later development of the Ionic, initially apparently only used inside buildings, and using Ionic forms for everything except the capitals. The famous and well-preserved Choragic Monument of Lysicrates near the Acropolis of Athens (335/334) is the first known use of the Corinthian order on the exterior of a building.[90]

Most of the best known surviving Greek buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, are Doric. The Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. The Ionic order became dominant in the Hellenistic period, since its more decorative style suited the aesthetic of the period better than the more restrained Doric. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus, can be seen in Turkey, at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum.[91] But in the greatest of Hellenistic cities, Alexandria in Egypt, almost nothing survives.

Model of the processional way at Ancient Delphi, without much of the statuary shown.[92]

Model of the processional way at Ancient Delphi, without much of the statuary shown.[92].jpg.webp) The Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, 4th century BC

The Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, 4th century BC The Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens, late 5th century BC

The Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens, late 5th century BC Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, 335/334

Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, 335/334

Coin design

Coins were (probably) invented in Lydia in the 7th century BC, but they were first extensively used by the Greeks,[93] and the Greeks set the canon of coin design which has been followed ever since. Coin design today still recognisably follows patterns descended from ancient Greece. The Greeks did not see coin design as a major art form, although some were expensively designed by leading goldsmiths, especially outside Greece itself, among the Central Asian kingdoms and in Sicilian cities keen to promote themselves. Nevertheless, the durability and abundance of coins have made them one of the most important sources of knowledge about Greek aesthetics.[94] Greek coins are the only art form from the ancient Greek world which can still be bought and owned by private collectors of modest means.

The most widespread coins, used far beyond their native territories and copied and forged by others, were the Athenian tetradrachm, issued from c. 510 to c. 38 BC, and in the Hellenistic age the Macedonian tetradrachm, both silver.[95] These both kept the same familiar design for long periods.[96] Greek designers began the practice of putting a profile portrait on the obverse of coins. This was initially a symbolic portrait of the patron god or goddess of the city issuing the coin: Athena for Athens, Apollo at Corinth, Demeter at Thebes and so on. Later, heads of heroes of Greek mythology were used, such as Heracles on the coins of Alexander the Great.

The first human portraits on coins were those of Achaemenid Empire Satraps in Asia Minor, starting with the exiled Athenian general Themistocles who became a Satrap of Magnesia c. 450 BC, and continuing especially with the dynasts of Lycia towards the end of the 5th century.[97] Greek cities in Italy such as Syracuse began to put the heads of real people on coins in the 4th century BC, as did the Hellenistic successors of Alexander the Great in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere.[98] On the reverse of their coins the Greek cities often put a symbol of the city: an owl for Athens, a dolphin for Syracuse and so on. The placing of inscriptions on coins also began in Greek times. All these customs were later continued by the Romans.[94]

The most artistically ambitious coins, designed by goldsmiths or gem-engravers, were often from the edges of the Greek world, from new colonies in the early period and new kingdoms later, as a form of marketing their "brands" in modern terms.[99] Of the larger cities, Corinth and Syracuse also issued consistently attractive coins. Some of the Greco-Bactrian coins are considered the finest examples of Greek coins with large portraits with "a nice blend of realism and idealization", including the largest coins to be minted in the Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by Eucratides (reigned 171–145 BC), the largest silver coin by the Indo-Greek king Amyntas Nikator (reigned c. 95–90 BC). The portraits "show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland depictions of their royal contemporaries further West".[100]

Heracles fighting the Nemean lion. Silver coin from Heraclea Lucania

Heracles fighting the Nemean lion. Silver coin from Heraclea Lucania Arethusa on a coin of Syracuse, Sicily, 415–400

Arethusa on a coin of Syracuse, Sicily, 415–400

Painting

The Greeks seem to have valued painting above even sculpture, and by the Hellenistic period the informed appreciation and even the practice of painting were components in a gentlemanly education. The ekphrasis was a literary form consisting of a description of a work of art, and we have a considerable body of literature on Greek painting and painters, with further additions in Latin, though none of the treatises by artists that are mentioned have survived.[101] We have hardly any of the most prestigious sort of paintings, on wood panel or in fresco, that this literature was concerned with.

The contrast with vase-painting is total. There are no mentions of that in literature at all, but over 100,000 surviving examples, giving many individual painters a respectable surviving oeuvre.[102] Our idea of what the best Greek painting was like must be drawn from a careful consideration of parallels in vase-painting, late Greco-Roman copies in mosaic and fresco, some very late examples of actual painting in the Greek tradition, and the ancient literature.[103]

There were several interconnected traditions of painting in ancient Greece. Due to their technical differences, they underwent somewhat differentiated developments. Early painting seems to have developed along similar lines to vase-painting, heavily reliant on outline and flat areas of colour, but then flowered and developed at the time that vase-painting went into decline. By the end of the Hellenistic period, technical developments included modelling to indicate contours in forms, shadows, foreshortening, some probably imprecise form of perspective, interior and landscape backgrounds, and the use of changing colours to suggest distance in landscapes, so that "Greek artists had all the technical devices needed for fully illusionistic painting".[104]

Panel and wall painting

The most common and respected form of art, according to authors like Pliny or Pausanias, were panel paintings, individual, portable paintings on wood boards. The techniques used were encaustic (wax) painting and tempera. Such paintings normally depicted figural scenes, including portraits and still-lifes; we have descriptions of many compositions. They were collected and often displayed in public spaces. Pausanias describes such exhibitions at Athens and Delphi. We know the names of many famous painters, mainly of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, from literature (see expandable list to the right). The most famous of all ancient Greek painters was Apelles of Kos, whom Pliny the Elder lauded as having "surpassed all the other painters who either preceded or succeeded him."[105][106]

Due to the perishable nature of the materials used and the major upheavals at the end of antiquity, not one of the famous works of Greek panel painting has survived, nor even any of the copies that doubtlessly existed, and which give us most of our knowledge of Greek sculpture. We have slightly more significant survivals of mural compositions. The most important surviving Greek examples from before the Roman period are the fairly low-quality Pitsa panels from c. 530 BC,[107] the Tomb of the Diver from Paestum, and various paintings from the royal tombs at Vergina. More numerous paintings in Etruscan and Campanian tombs are based on Greek styles. In the Roman period, there are a number of wall paintings in Pompeii and the surrounding area, as well as in Rome itself, some of which are thought to be copies of specific earlier masterpieces.[108]

In particular copies of specific wall-paintings have been confidently identified in the Alexander Mosaic and Villa Boscoreale.[109] There is a large group of much later Greco-Roman archaeological survivals from the dry conditions of Egypt, the Fayum mummy portraits, together with the similar Severan Tondo, and a small group of painted portrait miniatures in gold glass.[110] Byzantine icons are also derived from the encaustic panel painting tradition, and Byzantine illuminated manuscripts sometimes continued a Greek illusionistic style for centuries.

The tradition of wall painting in Greece goes back at least to the Minoan and Mycenaean Bronze Age, with the lavish fresco decoration of sites like Knossos, Tiryns and Mycenae. It is not clear, whether there is any continuity between these antecedents and later Greek wall paintings.

Wall paintings are frequently described in Pausanias, and many appear to have been produced in the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Due to the lack of architecture surviving intact, not many are preserved. The most notable examples are a monumental Archaic 7th-century BC scene of hoplite combat from inside a temple at Kalapodi (near Thebes), and the elaborate frescoes from the 4th-century "Grave of Phillipp" and the "Tomb of Persephone" at Vergina in Macedonia, or the tomb at Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, sometimes suggested to be closely linked to the high-quality panel paintings mentioned above. The unusual survival of the Tomb of the Palmettes (3rd-century BC, excavated in 1971) with painting in good condition includes portraits of the couple buried inside on the tympanum.

Greek wall painting tradition is also reflected in contemporary grave decorations in the Greek colonies in Italy, e.g. the famous Tomb of the Diver at Paestum. Some scholars suggest that the celebrated Roman frescoes at sites like Pompeii are the direct descendants of Greek tradition, and that some of them copy famous panel paintings.

Ancient Macedonian paintings of armour, arms, and gear from the Tomb of Lyson and Kallikles in ancient Mieza (modern-day Lefkadia), Imathia, Central Macedonia, Greece, 2nd century BC.

Ancient Macedonian paintings of armour, arms, and gear from the Tomb of Lyson and Kallikles in ancient Mieza (modern-day Lefkadia), Imathia, Central Macedonia, Greece, 2nd century BC. A stele of Dioskourides, dated 2nd century BC, showing a Ptolemaic thyreophoros soldier, a characteristic example of the "Romanization" of the Ptolemaic army

A stele of Dioskourides, dated 2nd century BC, showing a Ptolemaic thyreophoros soldier, a characteristic example of the "Romanization" of the Ptolemaic army Fresco from the Tomb of Judgment in ancient Mieza (modern-day Lefkadia), Imathia, Central Macedonia, Greece, depicting religious imagery of the afterlife, 4th century BC

Fresco from the Tomb of Judgment in ancient Mieza (modern-day Lefkadia), Imathia, Central Macedonia, Greece, depicting religious imagery of the afterlife, 4th century BC A fresco showing Hades and Persephone riding in a chariot, from the tomb of Queen Eurydice I of Macedon at Vergina, Greece, 4th century BC

A fresco showing Hades and Persephone riding in a chariot, from the tomb of Queen Eurydice I of Macedon at Vergina, Greece, 4th century BC A banquet scene from a Macedonian tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, 4th century BC; six men are shown reclining on couches, with food arranged on nearby tables, a male servant in attendance, and female musicians providing entertainment.[111]

A banquet scene from a Macedonian tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, 4th century BC; six men are shown reclining on couches, with food arranged on nearby tables, a male servant in attendance, and female musicians providing entertainment.[111] Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier (thorakitai) wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC

Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier (thorakitai) wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC The Sampul tapestry, a woollen wall hanging from Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, showing a possibly Greek soldier from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–125 BC), with blue eyes, wielding a spear, and wearing what appears to be a diadem headband; depicted above him is a centaur, from Greek mythology, a common motif in Hellenistic art;[112] Xinjiang Region Museum.

The Sampul tapestry, a woollen wall hanging from Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, showing a possibly Greek soldier from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–125 BC), with blue eyes, wielding a spear, and wearing what appears to be a diadem headband; depicted above him is a centaur, from Greek mythology, a common motif in Hellenistic art;[112] Xinjiang Region Museum. A Hellenistic Greek encaustic painting on a marble tombstone depicting the portrait of a young man named Theodoros, dated 1st century BC during the period of Roman Greece, Archaeological Museum of Thebes

A Hellenistic Greek encaustic painting on a marble tombstone depicting the portrait of a young man named Theodoros, dated 1st century BC during the period of Roman Greece, Archaeological Museum of Thebes

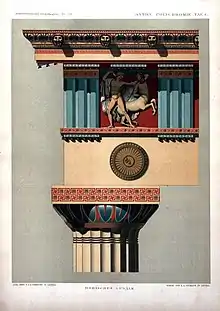

Polychromy: painting on statuary and architecture

Much of the figural or architectural sculpture of ancient Greece was painted colourfully. This aspect of Greek stonework is described as polychrome (from Greek πολυχρωμία, πολύ = many and χρώμα = colour). Due to intensive weathering, polychromy on sculpture and architecture has substantially or totally faded in most cases.

Although the word polychrome is created from the combining of two Greek words, it was not used in ancient Greece. The term was coined in the early nineteenth century by Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy.[113]

Architecture

Painting was also used to enhance the visual aspects of architecture. Certain parts of the superstructure of Greek temples were habitually painted since the Archaic period. Such architectural polychromy could take the form of bright colours directly applied to the stone (evidenced e.g. on the Parthenon, or of elaborate patterns, frequently architectural members made of terracotta (Archaic examples at Olympia and Delphi). Sometimes, the terracottas also depicted figural scenes, as do the 7th-century BC terracotta metopes from Thermon.[114]

Sculpture

Most Greek sculptures were painted in strong and bright colors; this is called "polychromy". The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. The painting of Greek sculpture should not merely be seen as an enhancement of their sculpted form, but has the characteristics of a distinct style of art.[115]

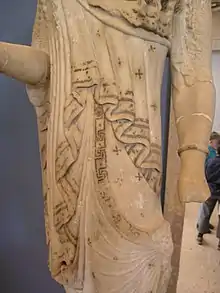

For example, the pedimental sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina have recently been demonstrated to have been painted with bold and elaborate patterns, depicting, amongst other details, patterned clothing. The polychromy of stone statues was paralleled by the use of different materials to distinguish skin, clothing and other details in chryselephantine sculptures, and by the use of different metals to depict lips, fingernails, etc. on high-quality bronzes like the Riace bronzes.[115]

Vase painting

The most copious evidence of ancient Greek painting survives in the form of vase paintings. These are described in the "pottery" section above. They give at least some sense of the aesthetics of Greek painting. The techniques involved, however, were very different from those used in large-format painting. The same probably applies to the subject matter depicted. Vase painters appear to have usually been specialists within a pottery workshop, neither painters in other media nor potters. It should also be kept in mind that vase painting, albeit by far the most conspicuous surviving source on ancient Greek painting, was not held in the highest regard in antiquity, and is never mentioned in Classical literature.[116]

Mosaics

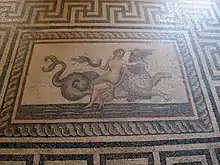

Mosaics were initially made with rounded pebbles, and later glass with tesserae which gave more colour and a flat surface. They were popular in the Hellenistic period, at first as decoration for the floors of palaces, but eventually for private homes.[118] Often a central emblema picture in a central panel was completed in much finer work than the surrounding decoration.[119] Xenia motifs, where a house showed examples of the variety of foods guests might expect to enjoy, provide most of the surviving specimens of Greek still-life. In general mosaic must be considered as a secondary medium copying painting, often very directly, as in the Alexander Mosaic.[120]

The Unswept Floor by Sosus of Pergamon (c. 200 BC) was an original and famous trompe-l'œil piece, known from many Greco-Roman copies. According to John Boardman, Sosus is the only mosaic artist whose name has survived; his Doves are also mentioned in literature and copied.[121] However, Katherine M. D. Dunbabin asserts that two different mosaic artists left their signatures on mosaics of Delos.[122] The artist of the 4th-century BC Stag Hunt Mosaic perhaps also left his signature as Gnosis, although this word may be a reference to the abstract concept of knowledge.[123]

Mosaics are a significant element of surviving Macedonian art, with a large number of examples preserved in the ruins of Pella, the ancient Macedonian capital, in today's Central Macedonia.[124] Mosaics such as the "Stag Hunt Mosaic and Lion Hunt" mosaic demonstrate illusionist and three dimensional qualities generally found in Hellenistic paintings, although the rustic Macedonian pursuit of hunting is markedly more pronounced than other themes.[125] The 2nd-century-BC mosaics of Delos, Greece were judged by François Chamoux as representing the pinnacle of Hellenistic mosaic art, with similar styles that continued throughout the Roman period and perhaps laid the foundations for the widespread use of mosaics in the Western world through to the Middle Ages.[118]

A mosaic of the Kasta Tomb in Amphipolis depicting the abduction of Persephone by Pluto, 4th century BC

A mosaic of the Kasta Tomb in Amphipolis depicting the abduction of Persephone by Pluto, 4th century BC Alexander the Great (left), wearing a kausia and fighting an Asiatic lion with his friend Craterus (detail); late 4th-century BC mosaic from Pella[126]

Alexander the Great (left), wearing a kausia and fighting an Asiatic lion with his friend Craterus (detail); late 4th-century BC mosaic from Pella[126]

.jpg.webp) Detail of floor panel with Alexandrine parakeet, Pergamon modern Turkey, middle 2nd century BC (reigns of Eumenes II and Attalus II)

Detail of floor panel with Alexandrine parakeet, Pergamon modern Turkey, middle 2nd century BC (reigns of Eumenes II and Attalus II) Ptolemaic mosaic of a dog and askos wine vessel from Hellenistic Egypt, dated 200-150 BC

Ptolemaic mosaic of a dog and askos wine vessel from Hellenistic Egypt, dated 200-150 BC Hellenistic mosaic from Thmuis (Mendes), Egypt, signed by Sophilos c. 200 BC; Ptolemaic Queen Berenice II (joint ruler with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.[127]

Hellenistic mosaic from Thmuis (Mendes), Egypt, signed by Sophilos c. 200 BC; Ptolemaic Queen Berenice II (joint ruler with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.[127]

Engraved gems

The engraved gem was a luxury art with high prestige; Pompey and Julius Caesar were among later collectors.[128] The technique has an ancient tradition in the Near East, and cylinder seals, whose design only appears when rolled over damp clay, from which the flat ring type developed, spread to the Minoan world, including parts of Greece and Cyprus. The Greek tradition emerged under Minoan influence on mainland Helladic culture, and reached an apogee of subtlety and refinement in the Hellenistic period.[129]

Round or oval Greek gems (along with similar objects in bone and ivory) are found from the 8th and 7th centuries BC, usually with animals in energetic geometric poses, often with a border marked by dots or a rim.[130] Early examples are mostly in softer stones. Gems of the 6th century are more often oval,[131] with a scarab back (in the past this type was called a "scarabaeus"), and human or divine figures as well as animals; the scarab form was apparently adopted from Phoenicia.[132]

The forms are sophisticated for the period, despite the usually small size of the gems.[96] In the 5th century gems became somewhat larger, but still only 2–3 centimetres tall. Despite this, very fine detail is shown, including the eyelashes on one male head, perhaps a portrait. Four gems signed by Dexamenos of Chios are the finest of the period, two showing herons.[133]

Relief carving became common in 5th century BC Greece, and gradually most of the spectacular carved gems were in relief. Generally a relief image is more impressive than an intaglio one; in the earlier form the recipient of a document saw this in the impressed sealing wax, while in the later reliefs it was the owner of the seal who kept it for himself, probably marking the emergence of gems meant to be collected or worn as jewellery pendants in necklaces and the like, rather than used as seals – later ones are sometimes rather large to use to seal letters. However inscriptions are usually still in reverse ("mirror-writing") so they only read correctly on impressions (or by viewing from behind with transparent stones). This aspect also partly explains the collecting of impressions in plaster or wax from gems, which may be easier to appreciate than the original.

Larger hardstone carvings and cameos, which are rare in intaglio form, seem to have reached Greece around the 3rd century; the Farnese Tazza is the only major surviving Hellenistic example (depending on the dates assigned to the Gonzaga Cameo and the Cup of the Ptolemies), but other glass-paste imitations with portraits suggest that gem-type cameos were made in this period.[134] The conquests of Alexander had opened up new trade routes to the Greek world and increased the range of gemstones available.[135]

Ornament

The synthesis in the Archaic period of the native repertoire of simple geometric motifs with imported, mostly plant-based, motifs from further east created a sizeable vocabulary of ornament, which artists and craftsmen used with confidence and fluency.[136] Today this vocabulary is seen above all in the large corpus of painted pottery, as well as in architectural remains, but it would have originally been used in a wide range of media, as a later version of it is used in European Neoclassicism.

Elements in this vocabulary include the geometrical meander or "Greek key", egg-and-dart, bead and reel, Vitruvian scroll, guilloche, and from the plant world the stylized acanthus leaves, volute, palmette and half-palmette, plant scrolls of various kinds, rosette, lotus flower, and papyrus flower. Originally used prominently on Archaic vases, as figurative painting developed these were usually relegated to serve as borders demarcating edges of the vase or different zones of decoration.[137] Greek architecture was notable for developing sophisticated conventions for using mouldings and other architectural ornamental elements, which used these motifs in a harmoniously integrated whole.

Even before the Classical period, this vocabulary had influenced Celtic art, and the expansion of the Greek world after Alexander, and the export of Greek objects still further afield, exposed much of Eurasia to it, including the regions in the north of the Indian subcontinent where Buddhism was expanding, and creating Greco-Buddhist art. As Buddhism spread across Central Asia to China and the rest of East Asia, in a form that made great use of religious art, versions of this vocabulary were taken with it and used to surround images of buddhas and other religious images, often with a size and emphasis that would have seemed excessive to the ancient Greeks. The vocabulary was absorbed into the ornament of India, China, Persia and other Asian countries, as well as developing further in Byzantine art.[138] The Romans took over the vocabulary more or less in its entirety, and although much altered, it can be traced throughout European medieval art, especially in plant-based ornament.

Islamic art, where ornament largely replaces figuration, developed the Byzantine plant scroll into the full, endless arabesque, and especially from the Mongol conquests of the 14th century received new influences from China, including the descendants of the Greek vocabulary.[139] From the Renaissance onwards, several of these Asian styles were represented on textiles, porcelain and other goods imported into Europe, and influenced ornament there, a process that still continues.

Other arts

.jpg.webp)

Right: Hellenistic satyr who wears a rustic perizoma (loincloth) and carries a pedum (shepherd's crook). Ivory appliqué, probably for furniture.

Although glass was made in Cyprus by the 9th century BC, and was considerably developed by the end of the period, there are only a few survivals of glasswork from before the Greco-Roman period that show the artistic quality of the best work.[140] Most survivals are small perfume bottles, in fancy coloured "feathered" styles similar to other Mediterranean glass.[141] Hellenistic glass became cheaper and accessible to a wider population.

No Greek furniture has survived, but there are many images of it on vases and memorial reliefs, for example that to Hegeso. It was evidently often very elegant, as were the styles derived from it from the 18th century onwards. Some pieces of carved ivory that were used as inlays have survived, as at Vergina, and a few ivory carvings; this was a luxury art that could be of very fine quality.[142]

It is clear from vase paintings that the Greeks often wore elaborately patterned clothes, and skill at weaving was the mark of the respectable woman. Two luxurious pieces of cloth survive, from the tomb of Philip of Macedon.[143] There are numerous references to decorative hangings for both homes and temples, but none of these have survived.

Diffusion and legacy

Ancient Greek art has exercised considerable influence on the culture of many countries all over the world, above all in its treatment of the human figure. In the West Greek architecture was also hugely influential, and in both East and West the influence of Greek decoration can be traced to the modern day. Etruscan and Roman art were largely and directly derived from Greek models,[144] and Greek objects and influence reached into Celtic art north of the Alps,[145] as well as all around the Mediterranean world and into Persia.[146]

In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, which was greatly aided by the spread of Buddhism, which early on picked up many Greek traits and motifs in Greco-Buddhist art, which were then transmitted as part of a cultural package to East Asia, even as far as Japan, among artists who were no doubt completely unaware of the origin of the motifs and styles they used.[147]

Following the Renaissance in Europe, the humanist aesthetic and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists, with a major revival in the movement of Neoclassicism which began in the mid-18th century, coinciding with easier access from Western Europe to Greece itself, and a renewed importation of Greek originals, most notoriously the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world.[148]

Historiography

The Hellenized Roman upper classes of the Late Republic and Early Empire generally accepted Greek superiority in the arts without many quibbles, though the praise of Pliny for the sculpture and painting of pre-Hellenistic artists may be based on earlier Greek writings rather than much personal knowledge. Pliny and other classical authors were known in the Renaissance, and this assumption of Greek superiority was again generally accepted. However critics in the Renaissance and much later were unclear which works were actually Greek.[149]

As a part of the Ottoman Empire, Greece itself could only be reached by a very few western Europeans until the mid-18th century. Not only the Greek vases found in the Etruscan cemeteries, but also (more controversially) the Greek temples of Paestum were taken to be Etruscan, or otherwise Italic, until the late 18th century and beyond, a misconception prolonged by Italian nationalist sentiment.[149]

The writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, especially his books Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1750) and Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums ("History of Ancient Art", 1764) were the first to distinguish sharply between ancient Greek, Etruscan, and Roman art, and define periods within Greek art, tracing a trajectory from growth to maturity and then imitation or decadence that continues to have influence to the present day.[150]

The full disentangling of Greek statues from their later Roman copies, and a better understanding of the balance between Greekness and Roman-ness in Greco-Roman art was to take much longer, and perhaps still continues.[151] Greek art, especially sculpture, continued to enjoy an enormous reputation, and studying and copying it was a large part of the training of artists, until the downfall of Academic art in the late 19th century. During this period, the actual known corpus of Greek art, and to a lesser extent architecture, has greatly expanded. The study of vases developed an enormous literature in the late 19th and 20th centuries, much based on the identification of the hands of individual artists, with Sir John Beazley the leading figure. This literature generally assumed that vase-painting represented the development of an independent medium, only in general terms drawing from stylistic development in other artistic media. This assumption has been increasingly challenged in recent decades, and some scholars now see it as a secondary medium, largely representing cheap copies of now lost metalwork, and much of it made, not for ordinary use, but to deposit in burials.[152]

See also

| History of art |

|---|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Greek art |

|---|

|

| Ancient art history |

|---|

| Middle East |

| Asia |

| European prehistory |

| Classical art |

Notes

- Boardman, 3–4; Cook, 1–2

- Cook, 12

- Cook, 14–18

- Athena wearing the aegis, detail from a scene representing Heracles and Iolaos escorted by Athena, Apollo and Hermes. Belly of an Attic black-figured hydria, Cabinet des Médailles, Paris, Inv. 254.

- Home page Archived 2019-05-18 at the Wayback Machine of the Corpus vasorum antiquorum, accessed 16 May 2016

- Cook, 24–26

- Cook, 27–28; Boardman, 26, 32, 108–109; Woodford, 12

- Preface to Ancient Greek Pottery (Ashmolean Handbooks) by Michael Vickers (1991)

- Boardman, 86, quoted

- Cook, 24–29

- Apollo wearing a laurel or myrtle wreath, a white peplos and a red himation and sandals, seating on a lion-pawed diphros; he holds a kithara in his left hand and pours a libation with his right hand. Facing him, a black bird identified as a pigeon, a jackdaw, a crow (which may allude to his love affair with Coronis) or a raven (a mantic bird). Tondo of an Attic white-ground kylix attributed to the Pistoxenos Painter (or the Berlin Painter, or Onesimos). Diam. 18 cm (7 in.)

- Cook, 30, 36, 48–51

- Cook, 37–40, 30, 36, 42–48

- Cook, 29; Woodward, 170

- Boardman, 27; Cook, 34–38; Williams, 36, 40, 44; Woodford, 3–6

- Cook, 38–42; Williams, 56

- Woodford, 8–12; Cook, 42–51

- Woodford, 57–74; Cook, 52–57

- Boardman, 145–147; Cook, 56-57

- Trendall, Arthur D. (April 1989). Red Figure Vases of South Italy: A Handbook. Thames and Hudson. p. 17. ISBN 978-0500202258.

- Boardman, 185–187

- Boardman, 150; Cook, 159; Williams, 178

- Cook, 160

- Cook, 161–163

- Boardman, 64–67; Karouzou, 102

- Karouzou, 114–118; Cook, 162–163; Boardman, 131–132

- Cook, 159

- Cook, 159, quoted

- Rasmussen, xiii. However, since the metal vessels have not survived, "this attitude does not get us very far".

- Sowder, Amy. "Ancient Greek Bronze Vessels", in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. online (April 2008)

- Cook, 162; Boardman, 65–66

- Boardman, 185–187; Cook, 163

- Boardman, 131–132, 150, 355–356

- Boardman, 149–150

- Boardman, 131, 187; Williams, 38–39, 134–135, 154–155, 180–181, 172–173

- Boardman, 148; Williams, 164–165

- Boardman, 131–132; Williams, 188–189 for an example made for the Iberian Celtic market.

- Rhyton. The upper section of the luxury vessel used for drinking wines is wrought from silver plate with gilded edge with embossed ivy branch. The lower part goes in the cast Protoma horse. The work of the Greek master, probably for Thracian aristocrat. Perhaps Thrace, the end of the 4th century BC. NG Prague, Kinský Palace, NM-HM10 1407.

- Cook, 19

- Woodford, 39–56

- Cook, 82–85

- Smith, 11

- Cook, 86–91, 110–111

- Cook, 74–82

- Kenneth D. S. Lapatin. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-815311-2

- Cook, 74–76

- Boardman, 33–34

- Connor, Simon (1 January 2019). "Ashmawy, Aiman, Simon Connor, and Dietrich Raue 2019. Psamtik I in Heliopolis. Egyptian Archaeology 55, 34-39". Egyptian Archaeology: 38–39.

- Smith, William Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1 January 1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. Yale University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-300-07747-6.

- Cook, 99; Woodford, 44, 75

- Cook, 93

- Boardman, 47–52; Cook, 104–108; Woodford, 38–56

- Boardman, 47–52; Cook, 104–108; Woodford, 27–37

- Boardman, 92–103; Cook, 119–131; Woodford, 91–103, 110–133

- Tanner, Jeremy (2006). The Invention of Art History in Ancient Greece: Religion, Society and Artistic Rationalisation. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780521846141.

- CAHN, HERBERT A.; GERIN, DOMINIQUE (1988). "Themistocles at Magnesia". The Numismatic Chronicle. 148: 19. JSTOR 42668124.

- Boardman, 111–120; Cook, 128; Woodford, 91–103, 110–127

- Boardman, 135, 141; Cook, 128–129, 140; Woodford, 133

- Woodford, 128–134; Boardman, 136–139; Cook, 123–126

- Boardman, 119; Woodford, 128–130

- Smith, 7, 9

- Smith, 11, 19–24, 99

- Smith, 14–15, 255–261, 272

- Smith, 33–40, 136–140

- Smith, 127–154

- Smith, 77–79

- Smith, 99–104; Photo of Kneeling youthful Gaul, Louvre

- Smith, 104–126

- Smith, 240–241

- Smith, 258-261

- Smith, 206, 208-209

- Smith, 210

- Smith, 205

- "Bell idol", Louvre

- Williams, 182, 198–201; Boardman, 63–64; Smith, 86

- Williams, 42, 46, 69, 198

- Cook, 173–174

- Cook, 178, 183–184

- Cook, 178–179

- Cook, 184–191; Boardman, 166–169

- Cook, 186

- Cook, 190–191

- Cook, 241–244

- Boardman, 169–171

- Cook, 185–186

- Cook, 179–180, 186

- Cook, 193–238 gives a comprehensive summary

- Cook, 191–193

- Cook, 211–214

- Cook, 218

- Boardman, 159–160, 164–167

- another reconstruction

- Howgego, 1–2

- Cook, 171–172

- Howgego, 44–46, 48–51

- Boardman, 68–69

- "A rare silver fraction recently identified as a coin of Themistocles from Magnesia even has a bearded portrait of the great man, making it by far the earliest datable portrait coin. Other early portraits can be seen on the coins of Lycian dynasts." Carradice, Ian; Price, Martin (1988). Coinage in the Greek World. Seaby. p. 84. ISBN 9780900652820.

- Howgego, 63–67

- Williams, 112

- Roger Ling, "Greece and the Hellenistic World"

- Cook, 22, 66

- Cook, 24, says over 1,000 vase-painters have been identified by their style

- Cook, 59–70

- Cook, 59–69, 66 quoted

- Bostock, John. "Natural History". Perseus. Tufts University. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies 3rd ed. 1916, p. 329.

- Cook, 61;

- Boardman, 177–180

- Boardman, 174–177

- Boardman, 338–340; Williams, 333

- Cohen, 28

- Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012). Mair, Victor H. (ed.). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations (230): 15–16. ISSN 2157-9687.

- Sabatini, Paolo (2 May 2012). "Antoine Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy (1755-1849) and the Rediscovery of Polychromy in Grecian Architecture: Colour Techniques and Archaeological Research in the Pages of "Olympian Zeus."" (PDF).

- Cook, 182–183

- Woodford, 173–174; Cook, 75–76, 88, 93–94, 99

- Cook, 59–63

- See: Chugg, Andrew (2006). Alexander's Lovers. Raleigh, N.C.: Lulu. ISBN 978-1-4116-9960-1, pp 78-79.

- Chamoux, 375

- Boardman, 154

- Boardman, 174–175, 181–185

- Boardman, 183–184

- Dunbabin, 33

- Cohen, 32

- Hardiman, 517

- Hardiman, 518

- Palagia, Olga (2000). "Hephaestion's Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander". In Bosworth, A.B.; Baynham, E.J. (eds.). Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Oxford University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780198152873.

- Fletcher, Joann (2008). Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7, image plates and captions between pp. 246-247.

- for Caesar: De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius, (The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius), Fordham online text; for Pompey: Chapters 4–6 of Book 37 of the Natural History of Pliny the Elder give a summary art history of the Greek and Roman tradition, and of Roman collecting