Pope Clement XI

Pope Clement XI (Latin: Clemens XI; Italian: Clemente XI; 23 July 1649 – 19 March 1721), born Giovanni Francesco Albani, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 23 November 1700 to his death in March 1721.

Clement XI | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

.jpg.webp) Portrait by an unknown Italian School artist, 18th century, Vatican Museums | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 23 November 1700 |

| Papacy ended | 19 March 1721 |

| Predecessor | Innocent XII |

| Successor | Innocent XIII |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | September 1700 |

| Consecration | 30 November 1700 by Emmanuel-Theódose de la Tour d’Auvergne de Bouillon |

| Created cardinal | 13 February 1690 by Alexander VIII |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Giovanni Francesco Albani 23 July 1649 |

| Died | 19 March 1721 (aged 71) Rome, Papal States |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Clement | |

| Papal styles of Pope Clement XI | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Clement XI was a patron of the arts and of science. He was also a great benefactor of the Vatican Library; his interest in archaeology is credited with saving much of Rome's antiquity. He authorized expeditions which succeeded in rediscovering various ancient Christian writings and authorized excavations of the Roman catacombs.

Biography

Early life

Giovanni Francesco Albani was born in 1649 in Urbino to the Albani family, a distinguished family of Albanian origin in central Italy.[1][2][3] His mother Elena Mosca (1630–1698) was a high-standing Italian of bergamasque origin, descended from the noble Mosca family of Pesaro.[4] His father Carlo Albani (1623–1684) was a patrician. His mother descended in part from the Staccoli family,[4] who were patricians of Urbino, in part from the Giordani,[4] who were nobles of Pesaro.[5][6] The original name of the Albani was Lazzi (Laçi) which they changed to Albani in memory of their origin. Francesco Albani funded an expedition in Albania to locate the exact settlement of his family's origins. In the final report, the two most probable locations which were presented to him were Laç near Lezhë and Laç near Kukës, both in northern Albania.[7]

Albani was educated at the Collegio Romano in Rome from 1660 onwards. He became a very proficient Latinist and gained a doctorate in both canon and civil law. He was one of those who frequented the academy of Queen Christina of Sweden. He would serve as a papal prelate under Pope Alexander VIII and was appointed by Pope Innocent XII as the Referendary of the Apostolic Signatura. Throughout this time, he also served as the governor of Rieti, Sabina and Orvieto.

Cardinalate

Pope Alexander VIII elevated him to the cardinalate in 1690 despite his protests and made him the Cardinal-Deacon of Santa Maria in Aquiro but he later opted for the Diaconia of San Adriano al Forno and later, as the Cardinal-Priest, for the titulus of San Silvestro in Capite. He was then ordained to the priesthood in September 1700 and celebrated his first Mass in Rome on 6 October 1700.

Pontificate

Election to the papacy

Medal depicting Clement XI

Medal depicting Clement XI.jpg.webp)

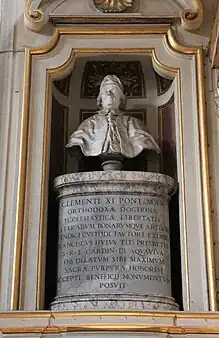

Bust of Pope Clement XI at Santa Cecilia church, Rome

Bust of Pope Clement XI at Santa Cecilia church, Rome

After the death of Pope Innocent XII in 1700, a conclave was convoked to elect a successor. Albani was regarded as a fine diplomat known for his skills as a peacemaker and so was unanimously elected pope on 23 November 1700. He agreed to the election after three days of consultation.

Unusually, from the viewpoint of current practice, his election came within three months after his ordination as a priest and within two months after he celebrated his first Mass, though he had been a cardinal for ten years previously. Having accepted election after some hesitation, he was ordained a bishop on 30 November 1700 and assumed the pontifical name of "Clement XI". Cardinal protodeacon Benedetto Pamphili crowned him on 8 December 1700 and he took possession of the Basilica of Saint John Lateran on 10 April 1701.

Actions

Soon after his accession to the pontificate, the War of the Spanish Succession broke out.

In 1703 Pope Clement XI ordered a synod of Catholic bishops in northern Albania that discussed promotion of the Council of Trent decrees within Albanian dioceses, stemming conversions among locals to Islam and securing agreement to deny communion to crypto-Catholics who outwardly professed the Muslim faith.[1][8][2]

Despite initially holding an ambiguous neutrality in world affairs, Clement XI was later forced to name Charles, Archduke of Austria, as the King of Spain, since the imperial army had conquered much of northern Italy and was threatening Rome itself in January 1709.

By the Treaty of Utrecht that put an end to the war, the Papal States lost their suzerainty over the Farnese Duchy of Parma and Piacenza in favour of Austria, and lost Comacchio as well, a blow to the prestige of the Papal States.

In 1713 Clement XI issued the bull Unigenitus in response to the spread of the Jansenist heresy. There followed great upheaval in France, where apart from theological issues, a strong Gallican tendency persisted. The bull, which was produced with the contribution of Gregorio Selleri, a lector at the College of Saint Thomas, the future Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum,[9] condemned Jansenism by extracting and anathematizing as heretical 101 propositions from the works of Quesnel, declaring them to be identical in substance with propositions already condemned in the writings of Jansenius.

The resistance of many French ecclesiastics and the refusal of the French parlements to register the bull led to controversies extending through the greater part of the 18th century. Because the local governments did not officially receive the bull, it was not, technically, in force in those areas – an example of the interference of states in religious affairs common before the 20th century.

Clement XI supported James Francis Edward Stuart, the exiled Stuart Prince by paying for their residence in Rome, the Palazzo Muti, as well as donating a summerhouse near the shores of Lake Albano.[10] He also performed the baptism of James' son Charles Edward Stuart.[10]

During his reign as a pope the famous Illyricum Sacrum was commissioned, and today it is one of the main sources of the field of Balkan region during Middle Ages, with over 5,000 pages divided in several volumes written by the Jesuit Daniele Farlati and Dom Jacopo Coleti.

Clement XI made a concerted effort to acquire Christian manuscripts in Syriac from Egypt and other places in the Middle East, greatly expanding the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana's collection of Syriac works.[11]

Other activities

Clement XI extended the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary to the Universal Church of the Roman Rite in 1716.

Beatifications and canonizations

Clement XI confirmed the cultus of Ceslas Odrowaz (27 August 1712), Jakov Varingez (29 December 1700), John of Perugia (11 September 1704), Peregrine Laziosi (11 September 1702), Peter of Sassoferrato (11 September 1704), Buonfiglio Monaldi (1 December 1717), Pope Gregory X (8 July 1713) and Humbeline of Jully (1703). He formally beatified a number of individuals: Alexis Falconieri, Bartholomew degli Amidei and Benedict Dellantella, (1 December 1717) and John Francis Régis (24 May 1716). He also beatified the sisters Theresa (20 May 1705) and Sancha (10 May 1705).

He canonized Andrew Avellino, Catherine of Bologna, Felix of Cantalice and Pope Pius V on 22 May 1712, Humility on 27 January 1720, Stephen of Obazine in 1701 and Boniface of Lausanne in 1702.

Clement XI, on 8 February 1720, named Saint Anselm of Canterbury as a Doctor of the Church, providing him the supplementary titles of "Doctor magnificus" ("Magnificent Doctor") and "Doctor Marianus" ("Marian Doctor").

Consistories

Clement XI created a total of 70 cardinals in 15 consistories. Notably, two cardinals of his own creation were Michelangelo dei Conti, who became his immediate successor, Pope Innocent XIII, and Lorenzo Corsini, who later became Pope Clement XII. The pope also nominated eight cardinals "in pectore", later publishing their names which validated their appointments as cardinals.

During his pontificate, Gabriele Filippucci resigned his cardinalate which the pope accepted on 7 June 1706. Clement XI also accepted the resignation of Francesco Maria de' Medici from the cardinalate on 19 June 1709.

Chinese Rites controversies

Another important decision of Clement XI was in regard to the Chinese Rites controversy: the Jesuit missionaries were forbidden to take part in honors paid to Confucius or the ancestors of the Emperors of China, which Clement XI identified as "idolatrous and barbaric", and to accommodate Christian language to pagan ideas under plea of conciliating the heathen.

Death and burial

Clement XI died in Rome on 19 March 1721 at 12:45pm and was buried in the pavement of Saint Peter's Basilica rather than in an ornate tomb like those of his predecessors.

On March 10, Clement XI had a meeting at about 11:00am with the Bishop of Sisteron Pierre François Lafitau. When the pope met with the bishop, he said that his time was drawing to a close and that he would soon die, despite protests to the contrary by Lafitau. On 14 March, Clement XI took ill while Lafitau was trying to get the pope's nephew to persuade the pope to name the French First Minister Guillaume Dubois to the cardinalate. However, Clement XI was in a state of delirium and was not responsive to his pleas. On 16 March, Quadragesima Sunday, the pope did not participate in the services, however, celebrated Mass in his private chapel at the Quirinale Palace. He took medication that day but experienced pains in his thorax and had trouble breathing from the cold air in his rooms.[12]

The following day, Clement XI celebrated Mass in his private chapel before meeting various prelates which included the Archbishop of Ravenna Geronimo Crispi. However, at around noon, he was suddenly struck with an extraordinary chill which was accompanied by a very strong fever that immediately forced him to his bed, with the pope declining a meal that evening. His pulse was exceptionally slow and he even coughed up a thick liquid that was streaked with blood. Unable to sleep that night, his fever abated somewhat. But the following day saw his fever return much more violently, and he had an irregular pulse. The sputum was foamy, once more with blood, indicating that there was something wrong with his lungs, causing his doctors to realize that his condition would more than likely prove fatal. Clement XI made his confession and the profession of faith before receiving Holy Communion at 8:00pm. James Francis Edward Stuart, the "Pretender", tried to see the dying pope, however he was denied on the grounds of the dangerous state of the pope's condition. That night, the papal sacristan and the Bishop of Porfirio, Niccolo Agostino degli Abbati Olivieri, Bishop of Porfirio, administered the Extreme Unction.[12]

On 19 March, the fever returned violently, and Clement XI slowly lost his ability to speak as his eyes clouded over and his respiration slowly diminished as the pope died just after midday.[12]

Contemporary influence

In his book "Journal of a Soul", while he was preparing for the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII resolved to pray the Universal Prayer and highly recommended it to others.

Construction activity and patronage

Pope Clement XI had a famous sundial added in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri and had an obelisk erected in the Piazza della Rotonda in front of the Pantheon, and a port built on the Tiber River, the beautiful porto di Ripetta, demolished at the end of the 19th century.

He established a committee, overseen by his favourite artists, Carlo Maratta and Carlo Fontana, to commission statuary of the apostles to complete the decoration of San Giovanni in Laterano. He also founded an academy of painting and sculpture on the Campidoglio.

He also enriched the Vatican library with numerous Oriental codices and lent his patronage to the first archaeological excavations in the Roman catacombs. In his native Urbino he restored numerous edifices and founded a public library.

Notes

- Frazee, Charles (2006). Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923. Cambridge University Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-0521027007. "...since the pope was of Albanian ancestry (demonstrated by his name of Albani)."

- Martucci, Donato (2010). I Kanun delle montagne albanesi: Fonti, fondamenti e mutazioni del diritto tradizionale albanese. Edizioni di Pagina. p. 154. ISBN 978-8874701223. "Nel 1703, per iniziativa di Papa Clemente XI (che era di origini albanesi) si tenne il primo Concilio Nazionale Albanese, in cui si cercò di promuovere l'applicazione dei decreti del Concilio di Trento nelle diocesi albanesi, di arginare la marea di conversioni all'islam"

- Bordoni, Linda (21 September 2014). "Fr Lombardi: Papal journey a blessing for all Albanians". Vatican Radio. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

...a silver portrait of Pope Clement XI – who belonged to the Albani family, so was traditionally of Albanian origin.

- "Family Tree of Giovanni Francesco Albani". geneanet.org. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Shahan, Thomas J. (1913). "Albani". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York Public Library: Robert Appleton Company. p. 255. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- Williams, George L. (2004). Papal Genealogy: The Families and Descendants of the Popes. McFarland. p. 116. ISBN 978-0786420711.

- Brunga 2021, p. 134.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). "Crypto-Christianity in the Balkan Area under the Ottomans". Slavic Review. 26 (2): 235–242. doi:10.2307/2492452. JSTOR 2492452. S2CID 163987636.

- "Pope Benedict XIII (1724–1730): Consistory of December 9, 1726 (VI)". Florida International University. Archived from the original on 17 January 2003. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Kybett, Susan M. (1988). Bonnie Prince Charlie: A Biography of Charles Edward Stuart. London: Unwin Hyman. p. 23. ISBN 978-0044403876.

- Heal, Kristian S. (2005). "Vatican Syriac Manuscripts: Volume 1". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 8 (1). Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- John Paul Adams (23 September 2015). "Sede Vacante 1721". CSUN. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

Sources

- Brunga, Liza (2021). Kishat e Zadrimës deri në prag të kuvendit të Arbërit (Thesis). Academy of Albanological Studies (Academy of Sciences of Albania).

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Rendina, Claudio (1983). I papi. Storia e segreti. Rome: Netwon & Compton. pp. 586–588.