Climate of Australia

Australia's climate is governed mostly by its size and by the hot, sinking air of the subtropical high pressure belt (subtropical ridge or Australian High). This moves north-west and north-east with the seasons. The climate is variable, with frequent droughts lasting several seasons, thought to be caused in part by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Australia has a wide variety of climates due to its large geographical size. The largest part of Australia is desert or semi-arid. Only the south-east and south-west corners have a temperate climate and moderately fertile soil. The northern part of the country has a tropical climate, varying between grasslands and desert. Australia holds many heat-related records: the continent has the hottest extended region year-round, the areas with the hottest summer climate, and the highest sunshine duration.

Because Australia is a medium-sized continent, separated from polar regions by the Southern Ocean, it is not subject to movements of frigid polar air during winter, of the type that sweep over the continents in the northern hemisphere during their winter. Consequently, Australia's winter is relatively mild, with less contrast between summer and winter temperatures than in the northern continents–though the transition is more dramatically marked in alpine regions of Australia and places of substantial elevation. Seasonal highs and lows can still be considerable. Temperatures have ranged from above 53 °C (127 °F) to as low as −23.0 °C (−9.4 °F). Minimum temperatures are moderated.

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation is associated with seasonal abnormality in many areas in the world. Australia is one of the continents most affected and experiences extensive droughts alongside considerable wet periods. Occasionally a dust storm will blanket a region and there are reports of the occasional tornado. Tropical cyclones, heat waves, bushfires and frosts in the country are also associated with the Southern Oscillation. Rising levels of salinity and desertification in some areas is ravaging the landscape.

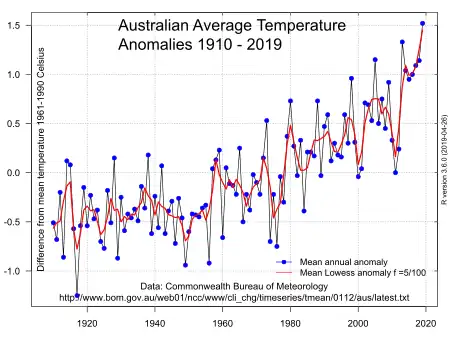

Climate change in Australia is a highly contentious political issue.[1][2] Temperatures in the country rose by approximately 0.7 °C between 1910 and 2004, following an increasing trend of global warming.[3] Overnight minimum temperatures have warmed more rapidly than daytime maximum temperatures in recent years. The late-20th century warming has been largely attributed to the increased greenhouse effect.[4] According to the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), 80% of the land receives less than 600 mm (24 in) of rainfall annually and 50% has even less than 300 mm (12 in).[5] As a whole, Australia has a very low annual average rainfall of 419 mm (16 in).[6]

States and territories

Australian Capital Territory

Because of its higher general elevation of over 650 m (2,130 ft), southern latitude and entirely landlocked location, winters are exclusively cool to cold in the Australian Capital Territory. Canberra has warm to hot, dry summers with some thunderstorms.[7] Heavy frosts are commonplace and radiation fog often occurs. Many of the higher mountains to the territory's west are snow-covered for a large part of the winter and early spring. Thunderstorms can occur between October and March, and annual rainfall is 623 mm (25 in), with rainfall highest in spring and summer and lowest in winter. The region is dry throughout its entirety due to its position on the leeward side of the Brindabella Ranges.

The highest temperature recorded in the ACT was 44.0 °C (111.2 °F) at Canberra Airport on 4 January 2020.[8] The lowest temperature was −14.6 °C (5.7 °F) at Gudgenby on 11 July 1971.[9]

New South Wales

Over half of New South Wales has an arid or semi-arid climate. The eastern portion has a temperate climate, ranging from humid subtropical from its northern border to the Central Coast and most of Sydney, and oceanic to the south coast. The Snowy Mountains region in the south-east falls in the alpine climate or subpolar oceanic climate zone, with cool to cold weather all year around and regular heavy snowfalls in the winter and spring. Further inland, the climate is semi-arid and a desert climate towards the western part of the state.

The weather in the southern half of the state is generally warm to hot in summer and cool in the winter. The seasons are more defined in the southern half of the state, especially in the South West Slopes, Central West and the Riverina regions. On the coast and anywhere east of the dividing range, a summer rainfall peak is observed throughout its entire latitudinal span. On the ranges and farther inland, rainfall usually peaks in spring in most parts of the state; though the South West Slopes region, in the south-central part of the state (bordering Victoria), has a distinct winter rainfall peak; whereas the New England and North West Slopes regions have a summer rainfall peak. On a hot summer day, a southerly buster may at times moderate the extreme heat experienced in the coastal New South Wales region, from Port Macquarie southwards to Nowra.[10]

The warmest region by annual maxima is the north-west, where summers are extremely hot, but winters relatively cooler and dry. The weather in the northeast region of the state, or the North Coast, bordering Queensland, is moderately hot, humid and rainy in the summer, and mild in winter with more sunshine; and little seasonal temperature difference. The Northern Tablelands have relatively milder summers and colder winters, due to their high elevation and inland location on the Great Dividing Range. The southeast coastal plain, which lies on the leeward side of the Great Dividing Range, experiences foehn winds, particularly between winter and spring, which can elevate fire danger.[11]

The coldest region is the Snowy Mountains where the snow and ice continues for a long period during the winter months. The Blue Mountains, Southern Tablelands and Central Tablelands, which are situated on the Great Dividing Range, have mild to warm summers and cold winters, although not as severe as those in the Snowy Mountains. The areas situated in the valleys of the range, such as Bathurst, Goulburn and Bowral, among other places, have recorded freezing and/or near-freezing lows even in the summer months, unlike other places of similar latitude and altitude in the northern hemisphere.

The highest maximum temperature recorded was 49.7 °C (121.5 °F) at Menindee in the state's west on 10 January 1939. The lowest minimum temperature was −23.0 °C (−9.4 °F) at Charlotte Pass on 29 June 1994 in the Snowy Mountains. This is also the lowest temperature recorded in the whole of Australia excluding Australian Antarctic Territory.[12]

Rainfall varies throughout the state. The far northwest receives the least, less than 180 mm (7 in) annually, while the east receives between 600 and 1,200 mm (24 and 47 in) of rain.

| Place | Climate type | January mean max. temp | January mean min. temp | July mean max. temp | July mean min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albury[13] | Cfa | 31 °C (88 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 4 °C (39 °F) | 108 | 699 mm (28 in) |

| Armidale[14] | Cfb | 26 °C (79 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 1 °C (34 °F) | 106[15] | 743 mm (29 in) |

| Broken Hill[16] | BWh | 33 °C (91 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 137 | 245 mm (10 in) |

| Charlotte Pass[17] | Cfc/Dfc | 18 °C (64 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 2 °C (36 °F) | −7 °C (19 °F) | 78 | 1,948 mm (77 in) |

| Coffs Harbour[18] | Cfa | 27 °C (81 °F) | 20 °C (68 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 122 | 1,668 mm (66 in) |

| Orange[19] | Cfb | 27 °C (81 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 10 °C (50 °F) | 2 °C (36 °F) | 100 | 927 mm (36 in) |

| Penrith[20] | Cfa | 31 °C (88 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 103 | 696 mm (27 in) |

| Sydney[21] (capital) | Cfa | 27 °C (81 °F) | 20 °C (68 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 9 °C (48 °F) | 104 | 1,150 mm (45 in) |

| Wagga Wagga[22] | Cfa | 32 °C (90 °F) | 16 °C (61 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 3 °C (37 °F) | 124 | 566 mm (22 in) |

| Wollongong[23] | Cfb | 26 °C (79 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 107 | 1,346 mm (53 in) |

Northern Territory

| Average monthly maximum temperature in Northern Territory | ||||

| Month | Darwin | Alice Springs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 31.8 °C (89.2 °F) | 36.4 °C (97.5 °F) | ||

| February | 31.4 °C (88.5 °F) | 35.1 °C (95.2 °F) | ||

| March | 31.9 °C (89.4 °F) | 32.7 °C (90.9 °F) | ||

| April | 32.7 °C (90.9 °F) | 28.2 °C (82.8 °F) | ||

| May | 32.0 °C (89.6 °F) | 23.0 °C (73.4 °F) | ||

| June | 30.6 °C (87.1 °F) | 19.8 °C (67.6 °F) | ||

| July | 30.5 °C (86.9 °F) | 19.7 °C (67.5 °F) | ||

| August | 31.3 °C (88.3 °F) | 22.5 °C (72.5 °F) | ||

| September | 32.5 °C (90.5 °F) | 27.2 °C (81.0 °F) | ||

| October | 33.2 °C (91.8 °F) | 31.0 °C (87.8 °F) | ||

| November | 33.3 °C (91.9 °F) | 33.6 °C (92.5 °F) | ||

| December | 32.6 °C (90.7 °F) | 35.4 °C (95.7 °F) | ||

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[24][25] | ||||

The Northern Territory has two distinctive climate zones. The northern end, including Darwin, has a tropical savannah climate (Köppen Aw)[26] with high humidity and two seasons, the wet (October to April) and dry season (May to September). During the dry season nearly every day is warm and sunny, and afternoon humidity averages around 30%. There is very little rainfall between May and September. In the coolest months of June and July, the daily minimum temperature may dip as low as 14 °C (57 °F), but very rarely lower, and frost has never been recorded.

The wet season is associated with tropical cyclones and monsoon rains. The majority of rainfall occurs between December and March (the Southern Hemisphere summer), when thunderstorms are common and afternoon relative humidity averages over 70% during the wettest months. On average more than 1,570 mm (62 in) of rain falls in the north. Thunderstorms can produce spectacular lightning displays.

The rest of the territory lies in the desert centre of the country; it includes Alice Springs and Uluru, and is arid or semi-arid with little rain usually falling during the hottest months from October to March. Its seasons are more defined than the northern parts, with summers being very hot, with average temperatures often exceeding 35 °C (95 °F), and winters relatively cool with average minimum temperatures dipping as low as 5 °C (41 °F), with a few frosty nights. Central Australia receives less than 250 mm (10 in) of annual rainfall.

The highest maximum temperature recorded in the territory was 48.3 °C (118.9 °F) at Finke on 1 and 2 January 1960. The lowest minimum temperature was −7.5 °C (18.5 °F) at Alice Springs on 12 July 1976.[12]

Queensland

Because of its size, there is significant variation in climate across the state. Low rainfall and hot summers are typical for the inland west, a monsoonal 'wet' season in the far north, and warm subtropical conditions along the coastal strip. Inland and in southern ranges cooler temperatures are experienced, especially at nights. The climate of the coastal strip is influenced by warm ocean waters, keeping the region free from extremes of temperature and providing moisture for rainfall.[27]

There are five predominant climatic zones in Queensland,[28] based on temperature and humidity:

- hot humid summer (far north and coastal)

- warm humid summer (coastal elevated hinterlands and coastal south-east)

- hot dry summer, mild winter (central west)

- hot dry summer, cold winter (southern west)

- temperate – warm summer, cold winter (inland south-east, e.g. Granite Belt)

However, most of the Queensland populace experience two weather seasons: a winter period of rather warm temperatures with minimal rainfall, and a sultry summer period of hot, sticky temperatures and more rain.

The highest maximum temperature observed in the state is 49.5 °C (121.1 °F) at Birdsville on 24 December 1972. The temperature of 53.1 °C (127.6 °F) at Cloncurry on 16 January 1889 is not considered official; the figure quoted from Birdsville is the next highest, so that record is considered as being official.

The lowest minimum temperature is −10.6 °C (12.9 °F) at Stanthorpe on 23 June 1961 and at The Hermitage on 12 July 1965.[12]

| Place | Climate type | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. Temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birdsville[29] | BWh | 39 °C (102 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 7 °C (45 °F) | 221 | 164 mm (6 in) |

| Brisbane[30] (capital) | Cfa | 30 °C (86 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 22 °C (72 °F) | 10 °C (50 °F) | 123 | 1,022 mm (40 in) |

| Cairns[31] | Am | 32 °C (90 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 90 | 1,982 mm (78 in) |

| Gold Coast[32] | Cfa | 29 °C (84 °F) | 22 °C (72 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | N/A | 1,273 mm (50 in) |

| Mackay[33] | Cfa | 30 °C (86 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 123 | 1,610 mm (63 in) |

| Mount Isa[34] | BSh | 37 °C (99 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 9 °C (48 °F) | 175 | 462 mm (18 in) |

| Rockhampton[35] | Cfa | 32 °C (90 °F) | 22 °C (72 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 10 °C (50 °F) | 116 | 812 mm (32 in) |

| Stanthorpe[36] | Cfb | 27 °C (81 °F) | 16 °C (61 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 1 °C (34 °F) | 42 | 762 mm (30 in) |

| Toowoomba[37] | Cfa | 28 °C (82 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 16 °C (61 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 114 | 952 mm (37 in) |

| Townsville[38] | Aw | 31 °C (88 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 121 | 1,132 mm (45 in) |

| Weipa[39] | Aw | 32 °C (90 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | 31 °C (88 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 54 | 1,911 mm (75 in) |

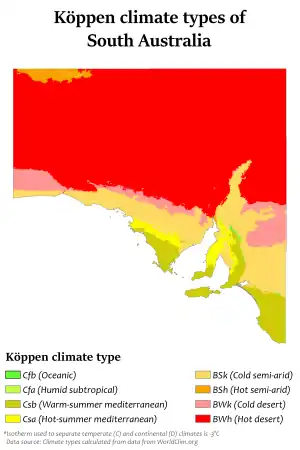

South Australia

The majority of the state has the arid and semi-arid climates. The southern coastal parts of the state have a Mediterranean climate with mild wet winters and hot dry summers. The highest rainfall occurs along the southern coasts and the Mount Lofty Ranges (with an average annual rainfall of 1,200 millimetres (47 in) in the vicinity of Mount Lofty); the lowest rainfall occurs in the Lake Eyre basin where the average annual totals are less than 150 millimetres (6 in) and possibly even 100 millimetres (4 in). Most of the rain in the southern districts of the State fall during the winter months when the sub-tropical high-pressure belt is displaced to the north over the Australian continent.[40]

South Australia's mean temperature range is 29 °C (84 °F) in January and 15 °C (59 °F) in July. Daily temperatures in parts of the state in January and February can be up to 50 °C (122 °F). The highest maximum temperature was recorded as 50.7 °C (123.3 °F) at Oodnadatta on 2 January 1960, which is the highest official temperature recorded in Australia. The lowest minimum temperature was −8.0 °C (17.6 °F) at Yongala on 20 July 1976.[12]

| Place | Climate type | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adelaide[41] (capital) | Csa | 29 °C (84 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 7 °C (45 °F) | 87 | 551 mm (22 in) |

| Kingscote[42] | Csb | 24 °C (75 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 62 | 489 mm (19 in) |

| Mount Gambier[43] | Csb | 25 °C (77 °F) | 11 °C (52 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 40 | 710 mm (28 in) |

| Oodnadatta[44] | BWh | 38 °C (100 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 20 °C (68 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 182 | 176 mm (7 in) |

| Port Augusta[45] | BWh | 34 °C (93 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 142 | 218 mm (9 in) |

| Stirling[46] | Csb/Cfb | 25 °C (77 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 11 °C (52 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 71 | 1,107 mm (44 in) |

| Whyalla[47] | BSh | 30 °C (86 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 63 | 267 mm (11 in) |

Tasmania

Tasmania has a cool temperate climate, with most areas under an oceanic climate (Cfb), with four distinct seasons. Summer lasts from December to February when the average maximum sea temperature is 21 °C (70 °F) and inland areas around Launceston reach 24 °C (75 °F). Other inland areas are much cooler; Liawenee, located on the Central Plateau, is one of the coldest places in Australia with February temperatures ranging between 4 and 17 °C (39 and 63 °F). Autumn lasts between March and May and experiences changeable weather, where summer weather patterns gradually take on the shape of winter patterns.[48]

The highest recorded maximum temperature in Tasmania was 42.2 °C (108.0 °F) at Scamander on 30 January 2009, during the 2009 south-eastern Australia heat wave. Tasmania's lowest recorded minimum temperature was −14.2 °C (6.4 °F) on 7 August 2020, at Liawenee.[49]

| Place | Climate type | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnie[50] | Cfb | 21 °C (70 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 52 | 958 mm (38 in) |

| Devonport[51] | Csb | 21 °C (70 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 56 | 773 mm (30 in) |

| Flinders Island[52] | Cfb | 22 °C (72 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 47 | 741 mm (29 in) |

| Hobart[53] (capital) | Cfb | 22 °C (72 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 41 | 615 mm (24 in) |

| King Island[54] | Csb | 21 °C (70 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 20 | 854 mm (34 in) |

| Launceston[55] | Cfb | 25 °C (77 °F) | 11 °C (52 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 2 °C (36 °F) | 50 | 630 mm (25 in) |

| Liawenee[56] | Csc | 19 °C (66 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | −2 °C (28 °F) | 22 | 923 mm (36 in) |

| Queenstown[57] | Cfb | 21 °C (70 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 2 °C (36 °F) | 29 | 2,405 mm (95 in) |

| St Helens[58] | Cfb | 23 °C (73 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | N/A | 666 mm (26 in) |

| Strahan[59] | Cfb | 21 °C (70 °F) | 11 °C (52 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 16 | 1,544 mm (61 in) |

Victoria

| Average monthly maximum temperature in Victoria | ||||

| Month | Melbourne | Mildura | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 25.8 °C (78.4 °F) | 32.8 °C (91.0 °F) | ||

| February | 25.8 °C (78.4 °F) | 32.7 °C (90.9 °F) | ||

| March | 23.8 °C (74.8 °F) | 29.3 °C (84.7 °F) | ||

| April | 20.2 °C (68.4 °F) | 24.1 °C (75.4 °F) | ||

| May | 16.6 °C (61.9 °F) | 19.6 °C (67.3 °F) | ||

| June | 14.0 °C (57.2 °F) | 16.0 °C (60.8 °F) | ||

| July | 13.4 °C (56.1 °F) | 15.4 °C (59.7 °F) | ||

| August | 14.9 °C (58.8 °F) | 17.7 °C (63.9 °F) | ||

| September | 17.2 °C (63.0 °F) | 21.1 °C (70.0 °F) | ||

| October | 19.6 °C (67.3 °F) | 25.0 °C (77.0 °F) | ||

| November | 21.8 °C (71.2 °F) | 29.0 °C (84.2 °F) | ||

| December | 24.1 °C (75.4 °F) | 31.7 °C (89.1 °F) | ||

| Source: BOM | ||||

Victoria has a varied climate despite its small size. It ranges from semi-arid and hot in the north-west, to temperate and cool along the coast. Victoria's main land feature, the Great Dividing Range, produces a cooler, mountain climate in the centre and east of the state.

The coastal plain south of the Great Dividing Range has Victoria's mildest climate. Regular frontal systems off the Southern Ocean significantly mitigate the heat of summer. Melbourne and other large cities are located in this temperate region.

The Mallee and upper Wimmera are Victoria's warmest regions with hot winds blowing from nearby deserts. Average temperatures top 32 °C (90 °F) during summer and 15 °C (59 °F) in winter. Victoria's highest maximum temperature of 48.8 °C (119.8 °F) was recorded in Hopetoun on 7 February 2009, during the 2009 south-eastern Australia heat wave.[12] A screen temperature of 50.7 °C (123.3 °F) was recorded on 7 January 1906 in Mildura.[60][61]

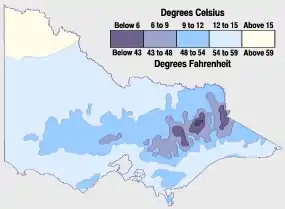

The Victorian Alps in the eastern and central regions constitute the coldest climate of Victoria. The Alps are part of the Great Dividing Range extending longitudinally through the centre of Victoria. Average maximum temperatures are less than 9 °C (48 °F) in winter; below 0 °C (32 °F) in the highest parts of the ranges. The state's lowest minimum temperature of −11.7 °C (10.9 °F) was recorded at Omeo on 13 June 1965, and again at Falls Creek on 3 July 1970.[12]

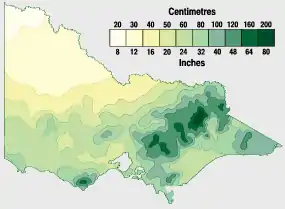

Victoria is the wettest Australian state after Tasmania. Rainfall in Victoria increases from north to south, with higher averages in areas of high altitude. Median annual rainfall exceeds 1,800 mm (71 in) in some parts of the Northeast but is less than 250 mm (10 in) in the Mallee.

Rain is heaviest in the Otway Ranges on the southwest coast and West Gippsland in South-Central Victoria, and in the mountainous Northeast. Snow often falls on the low-lying hilly country in the centre of the state, and on rare occasions may also fall to sea level. Rain falls most frequently in winter, but summer precipitation is heavier. Rainfall is most reliable in Gippsland and the Western District, making them both leading farming areas. Victoria's highest recorded daily rainfall was 375 millimetres (14.8 in) at Tanybryn in the Otway Ranges on 22 March 1983.[12]

| Place | Climate type | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bairnsdale[62] | Cfb | 26 °C (79 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 4 °C (39 °F) | 60 | 650 mm (26 in) |

| Ballarat[63] | Cfb | 25 °C (77 °F) | 11 °C (52 °F) | 10 °C (50 °F) | 3 °C (37 °F) | 55 | 690 mm (27 in) |

| Bendigo[64] | Cfa/Cfb | 30 °C (86 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 3 °C (37 °F) | 110 | 514 mm (20 in) |

| Falls Creek[65] | Cfc | 18 °C (64 °F) | 9 °C (48 °F) | 1 °C (34 °F) | −3 °C (27 °F) | N/A | 1,274 mm (50 in) |

| Geelong[66] | Cfb | 25 °C (77 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 38[67] | 524 mm (21 in) |

| Melbourne[68] (capital) | Cfb | 26 °C (79 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 49 | 648 mm (26 in) |

| Mildura[69] | BSk | 32 °C (90 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 4 °C (39 °F) | 132 | 291 mm (11 in) |

| Portland[70] | Csb/Cfb | 22 °C (72 °F) | 12 °C (54 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 40 | 840 mm (33 in) |

| Shepparton[71] | BSk | 32 °C (90 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 3 °C (37 °F) | N/A | 452 mm (18 in) |

| Warrnambool[72] | Cfb | 22 °C (72 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 13 °C (55 °F) | 6 °C (43 °F) | 53 | 743 mm (29 in) |

Source: BOM – Department of Primary Industries, Australian Natural Resources Atlas

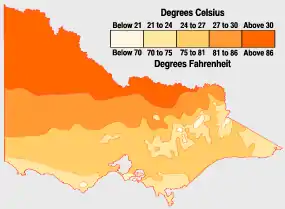

Average January temperatures: Victoria's north is always hotter than coastal and mountainous areas.

Average January temperatures: Victoria's north is always hotter than coastal and mountainous areas. Average July temperatures: Victoria's hills and ranges are coolest during winter. Snow also falls there.

Average July temperatures: Victoria's hills and ranges are coolest during winter. Snow also falls there. Average yearly precipitation: Victoria's rainfall is concentrated in the mountainous north-east and coast.

Average yearly precipitation: Victoria's rainfall is concentrated in the mountainous north-east and coast. Köppen map of Victoria

Köppen map of Victoria

Western Australia

Most of Western Australia has a hot arid and semi-arid climate. However, the south-west corner of the state has a Mediterranean climate.[73] The area was originally heavily forested, including large stands of the karri, one of the world's tallest trees. This agricultural region of Western Australia is in the top nine terrestrial habitats for terrestrial biodiversity, with a higher proportion of endemic species than most other equivalent regions. Due to the offshore Leeuwin Current, the area numbers in the top six regions for marine biodiversity, containing the most southerly coral reefs in the world.

Average annual rainfall varies from 300 mm (12 in) at the edge of the Wheatbelt region to 1,400 mm (55 in) in the wettest areas near Northcliffe, the southwesternmost tip of Australia, but in the months of November to March, although rain still falls, evaporation exceeds rainfall and it is generally very dry. Plants must be adapted to this as well as the extreme poverty of all soils. A major reduction in rainfall has been observed, with a greater number of rainfall events in the summer months. The central four-fifths of the state is semi-arid or desert and is lightly inhabited with the only significant activity being mining. Annual rainfall averages about 200 to 250 mm (8 to 10 in), most of which occurs in sporadic torrential falls related to cyclone events in summer months.

An exception to this is the northern tropical regions. The Kimberley has an extremely hot monsoonal climate with average annual rainfall ranging from 500 to 1,500 mm (20 to 59 in), but there is a very long dry season of 7 months from April to November. Eighty-five per cent of the state's runoff occurs in the Kimberley, but because it occurs in violent floods and because of the insurmountable poverty of the generally shallow soils, development has only taken place along the Ord River.

Australia's tropical/subtropical location and cold waters off the western coast make most of Western Australia a hot desert with aridity a marked feature of a greater part of the continent. These cold waters produce precious little moisture needed on the mainland. A 2005 study by Australian and American researchers[74] investigated the desertification of the interior, and suggested that one explanation was related to human settlers who arrived about 50,000 years ago.

Snowfall in the state is rare, and typically only in the Stirling Range near Albany, the southwesternmost point in WA, the only mountain range far enough south and with sufficient elevation. More rarely, snow can fall on the nearby Porongurup Range. Snow outside these areas is a major event; it usually occurs in hilly areas of south-western Australia. The most widespread low-level snow occurred on 26 June 1956 when snow was reported in the Perth Hills, as far north as Wongan Hills and as far east as Salmon Gums. However, even in the Stirling Range, snowfalls rarely exceed 5 cm (2 in) and rarely settle for more than one day.[75]

The highest observed maximum temperature of 50.5 °C (122.9 °F) was recorded at Mardie Station on 19 February 1998. The lowest minimum temperature recorded was −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) at Eyre Bird Observatory on 17 August 2008.[12]

| Place | Climate type | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albany[76] | Csb | 23 °C (73 °F) | 15 °C (59 °F) | 16 °C (61 °F) | 8 °C (46 °F) | 45 | 929 mm (37 in) |

| Broome[77] | BSh | 33 °C (91 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 29 °C (84 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 182 | 613 mm (24 in) |

| Eucla[78] | BSk | 26 °C (79 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 7 °C (45 °F) | 94 | 274 mm (11 in) |

| Geraldton[79] | Csa/BSh | 32 °C (90 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 9 °C (48 °F) | 164 | 441 mm (17 in) |

| Kalgoorlie[80] | BSk | 34 °C (93 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 151 | 266 mm (10 in) |

| Karratha[81] | BSh | 36 °C (97 °F) | 27 °C (81 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 158 | 297 mm (12 in) |

| Perth[82] (capital) | Csa | 30 °C (86 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 9 °C (48 °F) | 131 | 868 mm (34 in) |

| Wyndham[83] | BSh | 37 °C (99 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 31 °C (88 °F) | 17 °C (63 °F) | 176 | 824 mm (32 in) |

Distant Australian islands

| Island(s) | Climate type | Coordinates | January max. temp | January min. temp | July max. temp | July min. temp | No. clear days | Annual precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christmas Island[84] | Am | 10°25′18″S 105°40′41″E | 28 °C (82 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 23 °C (73 °F) | 8 | 2,199 mm (87 in) |

| Cocos (Keeling) Islands[85] | Am | 12°07′S 96°54′E | 30 °C (86 °F) | 25 °C (77 °F) | 28 °C (82 °F) | 24 °C (75 °F) | N/A | 1,984 mm (78 in) |

| Lord Howe Island[86] | Cfa | 31°33′15″S 159°05′06″E | 25 °C (77 °F) | 21 °C (70 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 68 | 1,464 mm (58 in) |

| Macquarie Island[87] | ET | 54°30′0″S 158°57′0″E | 9 °C (48 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 5 °C (41 °F) | 2 °C (36 °F) | 4 | 993 mm (39 in) |

| Norfolk Island[88] | Cfa | 29.03°S 167.95°E | 25 °C (77 °F) | 19 °C (66 °F) | 18 °C (64 °F) | 14 °C (57 °F) | 41 | 1,286 mm (51 in) |

| Willis Island[89] | Aw | 16°17′15″S 149°57′52″E | 31 °C (88 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 22 °C (72 °F) | 67 | 1,102 mm (43 in) |

Precipitation

Rain

More than 80% of Australia has an annual rainfall of less than 600 mm (24 in); among the continents, only Antarctica receives less rainfall.[91] A place inland near Lake Eyre (in South Australia) would only receive 81 mm (3 in) of rain annually.[92] Another place, Troudaninna Bore (29°11′44″S 138°59′28″E, altitude : 46 m) in South Australia, from 1893 to 1936, received, in average, 104.9 mm (4.13 inches) of precipitation.[93] From one extreme to another, parts of the far North Queensland coast annually average over 4,000 mm (157 in), with the Australian annual record being 12,461 mm (491 in), set at the summit of Mount Bellenden Ker in 2000. Four factors contribute to the dryness of the Australian landmass:

- Cold ocean currents off the west coast

- Low elevation of landforms

- Dominance of high-pressure systems

- Shape of the landmass

The average annual rainfall in the Australian desert is low, ranging from 81 to 250 mm (3 to 10 in). Thunderstorms are relatively common in the region, with an annual average of 15 to 20 thunderstorms.[94] Summer daytime temperatures range from 32 to 40 °C (90 to 104 °F); winter temperatures run 18 to 23 °C (64 to 73 °F).

The southern parts of Australia get the usual westerly winds and rain-bearing cold fronts that come when high–pressure systems move towards northern Australia during winter. Cold snaps may bring frosts inland, though temperatures near the coast are mild or near mild all year round. The Australian northwest cloudbands provides up to 80% of the annual rainfall for northwestern Australia and up to 40% of the annual rainfall for southwestern Australia, including most of the winter rainfall over northwest Western Australia and Central Australia.[95][96] Summers in southern Australia are generally dry and hot with coastal sea breezes. During a lengthy dry spell, hot and dry winds from the interior can cause bushfires in some southern and eastern states, though most commonly Victoria and New South Wales.

The tropical areas of northern Australia have a wet summer because of the monsoon. During "the wet", typically October to April, humid north-westerly winds bring showers and thunderstorms. Occasionally, tropical cyclones can bring heavy rainfall to tropical coastal regions, which is also likely to reach further inland. After the monsoonal season, the dry season comes ("winter"), which brings mostly clear skies and milder conditions.

Rainfall records tend to be concentrated along the east coast of Australia, particularly in tropical north Queensland. The highest 24‑hour rainfall on record in Australia was 907.0 millimetres (35.7 in) in Crohamhurst on 3 February 1893.[97] The highest monthly rainfall on record was 5,387.0 millimetres (212.1 in) recorded at Mount Bellenden Ker, Queensland in January 1979.[97] The highest annual rainfall was 12,461.0 millimetres (490.6 in) recorded also at Mount Bellenden Ker in 2000.[97] Additionally, the location which receives the highest average annual rainfall in Australia is Babinda in Queensland with an annual average of 4,279.4 millimetres (168.5 in).[98]

Cold ocean currents off the coast of Western Australia result in little evaporation occurring. Hence, rain clouds are sparsely formed and rarely do they form long enough for a continuous period of rain to be recorded. Australia's arid/semi-arid zone extends to this region. The absence of any significant mountain range or area of substantial height above sea level, results in very little rainfall caused by orographic uplift. In the east the Great Dividing Range limits rain moving into inland Australia.

Australia has a compact shape, and no significant bodies of water penetrate very far inland. This is important in as much as moist winds are prevented from penetrating inland, so keeping rainfall low.[99]

Snow

In Australia, snow falls frequently on the highlands of the southeast, in the states of Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania and in the Australian Capital Territory. There is a regular snow season in several areas which have seasonal ski tourism industries, such as Thredbo, Cabramurra, Mount Buller and Perisher Ski Resort, among others. Snow falls with some regularity above 900 metres (3,000 ft) on the Great Dividing Range, seldom as far north as Stanthorpe in southernmost Queensland and in isolated parts of South Australia and Western Australia, but outside these areas, snow is an extremely rare occurrence. Snow has also fallen on Uluru and near Alice Springs on at least one occasion.

Snow at sea level is occasionally recorded on mainland Australia (namely in southwestern and south-central Victoria), but is more frequent in western Tasmania where snowfalls at sea level can occur nigh to annually during the winter months; and in the extreme event of November 2021, snow was recorded to sea level on Bruny Island. Snow has been recorded across most of Tasmania, though it is rare on the eastern coast at sea level due to being leeward of the snow-bearing westerlies. Snow is rare in the southernmost capitals like Melbourne and Hobart, falling less than once every decade, and in the other capitals it is unknown (however snow has fallen in the hill suburbs of Perth and Adelaide). There are extensive, well-developed ski fields in the Great Dividing Range, a few hours' drive from Melbourne and Sydney.

Light snow generally falls once every few winters in Canberra and somewhat more regularly in the cities of Orange and Ballarat. However, there are many smaller towns that receive more regular seasonal snowfalls, such as Oberon, Crookwell, Cooma, Jindabyne, Batlow, Bombala and Omeo. West of the Great Dividing Range, particularly in the South West Slopes, snow is observed more frequently and to much lower altitudes than on the eastern side (even Parkes, Forbes and Wagga Wagga have recorded snow); the lowest recorded snowfall in New South Wales fell to an altitude of just 165 metres (541 ft) in Albury, most recently in July 1966. The snowiest proper towns in Australia are Trentham in west central Victoria, averaging 7.8 days per annum on which snow falls; and Nimmitabel in southern New South Wales, averaging 8.0 snowy days.[100][101] The isolated locality of Bendoc in East Gippsland averages 14.7 snowy days per annum, while Aberfeldy in West Gippsland averages an impressive 32.5 snowy days per annum.[102]

The occasional cold snap, caused by cold air drifting north from Antarctica, can cause significant snowfall in rural areas, as well as major cities such as Hobart, Melbourne's outer mountain suburbs and Canberra. Such occasions are rare, but have occurred in 1958, 1965, 1986, 2005 and 2015, the 1965 event causing snow to fall as far north as Eungella, near Mackay in tropical Queensland.[103] Extreme snow events have also produced snow as far north-west as Longreach in Queensland and in the ranges near Alice Springs, and also in lowland areas such as Dubbo and Gunnedah in northern New South Wales. The frequency and intensity of such events have been decreasing significantly over the past 40 years and the most northerly occurrence of snow in this time frame has been the Bunya Mountains in southern Queensland.[104]

Temperatures

The tropical savannah zone of Northern Australia is warm to hot all year. Summers are hot in most of the country with average January maximum temperatures exceeding 30 °C over most of the mainland, except for high elevations. Winters are warm in the north and cool in the south, with nightly frosts common in inland areas south of the Tropic of Capricorn. Only at the highly elevated areas do wintertime temperatures approach those found in much of Europe or North America, especially the southern parts.

Temperatures in Australia have followed an increasing trend between the years of 1910 and 2004 by approximately 0.7 °C. Overnight minimum temperatures have warmed more rapidly than daytime maximum temperatures. The observed warming has hastened in recent years. The late-20th-century warming has been largely attributed to the increased greenhouse effect.[105] Temperature differences between winter and summer are minor in the tropical region of Australia. However, they are greatest in the southern inland, with seasonal differences along the coast being moderated by the ocean's proximity. In July, a more common latitudinal distribution of average maximums is apparent, ranging from 30 °C near the north coast to below 3 °C in the mountainous areas of the south-east.[106]

Average minimum temperatures in all seasons are highest in northern Australia and near the coastal areas, and are lowest in the elevated areas of the south-east. The highest average January minimum temperatures (near 27 °C) are found near the north-west coast, while in winter they exceed 20 °C at some coastal locations in northern Australia and on the Torres Strait and Tiwi Islands. In the mountains of New South Wales, it is not unusual to have average low minimum temperatures dipping below 5 °C in January and −5 °C in July. Comparatively, most inland (non-mountainous) areas south of the tropics have average July minimum between 0 and 6 °C.

In the desert, the dry air and clear skies give rather large ranges in temperature between day and night. Ranges of 15 °C being typical and 20 °C not quite unusual. Light nighttime frosts in winter occur over much of the southern half of the arid zone, where mean July minimum temperatures are mostly in the 3 to 6 °C range. Moving north, frosts become increasingly rare, with mean July minimum being around 10 °C on the northern boundary.

The highest maximums in Australia are recorded in two regions, the Pilbara and Gascoyne regions of north-western Western Australia and the area extending from south-western Queensland across South Australia into south-eastern Western Australia. Many locations in this region have recorded temperatures exceeding 48 °C. In January, average maximum temperatures exceed 35 °C over a large area of the interior and exceed 40 °C over areas in the north-west. The highest summer maximums in the Pilbara and Gascoyne average at around 41 °C (in some years daily maximums consecutively exceed 40 °C for several weeks at a time).

Extremes

The most powerful heatwave in the history of south-eastern Australia occurred in January 1939. Adelaide (46.1 °C on the 12th), Melbourne (45.6 °C on the 13th) and Sydney (45.3 °C on the 14th) all had record-high temperatures during this period, as did many other central district areas in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. The record number of consecutive days in Melbourne over 40 °C is five, with Brisbane and Sydney each having two. Heatwaves usually bring by oppressively warm nights, with Oodnadatta, SA recording an Australian record of nine nights above 30 °C in February 2004.[107] Another extreme event was a prolonged period of extensive heatwaves known as the Angry Summer in early 2013.

Marble Bar achieved 160 consecutive days above 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) in 1923–24. Nyang had an average maximum of 44.8 °C for the months of February 1998 and January 2005, an Australian record. At the other extreme, average January maximums are near 15 °C on the highest peaks of the south-east ranges and near 20 °C in much of Tasmania. In most of the desert region during summer, cool days are rare and usually associated with major rain events—a rather exceptional example occurred in February 1949, when many areas failed to reach 20 °C on one or more days, and the maximum at Boulia, western Queensland was at 14.4 °C, which was 23 °C below normal.

Many other locations in Australia, except those above 500 metres, have extreme maximums between 43 and 48 °C. Most Tasmanian sites away from the north coast have had extreme maximums between 35 and 40 °C. The lowest extreme maximums are found along the north coast of Tasmania (e.g. 29.5 °C at Low Head) and at high elevations (27.0 °C at Thredbo). While extreme high temperatures are more common inland than they are near the coast, notable extreme maxima have been observed near the coast; 50.7 °C at Onslow, 50.5 °C at Mardie, 49.9 °C at Nullarbor, South Australia, 49.8 °C at Eucla, South Australia and 49.5 °C at Port Augusta, South Australia.[108]

At lower elevations, most inland places south of the tropics have extreme minimum between −3 and −7 °C, and these low temperatures have also occurred in locations within a few kilometres of southern and eastern coasts, such as Sale, Victoria (−5.6 °C), Bega, New South Wales (−8.1 °C), Grove, Tasmania (−7.5 °C) and Taree, New South Wales (−5.0 °C). Many locations in this region have recorded −10 °C or lower, including Gudgenby in the Australian Capital Territory (−14.6 °C) and Woolbrook, New South Wales (−14.5 °C). In the desert, the lowest extreme minimum occur at high elevations, especially around Alice Springs, where the temperature has fallen as low as −7.5 °C.

In the tropics, extreme minimum near or below 0 °C have occurred at many places distant from the coast, as far north as Herberton, Queensland (−5.0 °C). Some locations near tropical coasts, such as Mackay (−0.8 °C), Townsville (0.1 °C) and Kalumburu, Western Australia (0.3 °C) have also recorded temperatures near 0 °C. In contrast, some coastal locations, such as Darwin, have never fallen below 10 °C, and Thursday Island, in the Torres Strait, has an extreme minimum of 16.1 °C. The lowest maximum temperature on record in Australia was −6.9 °C (19.6 °F), recorded on 9 July 1978 at Thredbo Ski Resort in New South Wales.[109] The highest minimum temperature on record was 36.6 °C (97.9 °F) on 26 January 2019 at Borrona Downs Station near Wanaaring, New South Wales. Before this heatwave, the previous record was 35.5 °C (95.9 °F), recorded on 24 January 1982 in Arkaroola, South Australia and again on 21 January 2003 in Wittenoom, Western Australia.[110]

A list of extremes can be found in the tables below:

| Absolute temperature ranges | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Maximum temperatures | Minimum temperatures | ||||

| °C | °F | location and date | °C | °F | location and date | |

| January | 50.7 | 123.3 |

Oodnadatta, South Australia (2 January 1960)[111] |

−7.7 | 18.1 |

Thredbo Ski Resort, New South Wales (24 January 2000)[113] |

| February | 50.5 | 122.9 | −7.0 | 19.4 |

Perisher Ski Resort, New South Wales (17 February 1979)[115] | |

| March | 48.5 | 119.3 |

Emu Creek Station, Western Australia (11 March 2019)[116] |

−7.2 | 19.0 |

Kiandra, New South Wales (25 March 1964)/Bullocks Flat, New South Wales (31 March 1988)[117] |

| April | 45.0 | 113.0 |

Port Hedland, Western Australia (1 April 1948)/Marble Bar, Western Australia (2 April 1928)[118] |

−13.0 | 8.6 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (29 April 2009)[115] |

| May | 40.6 | 105.1 |

Bidyadanga, Western Australia (6 May 1990)[119] |

−13.4 | 7.9 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (24 May 2008)[120] |

| June | 37.8 | 100.0 | −23.0 | −9.4 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (29 June 1994)[122] | |

| July | 37.6 | 99.7 |

Wyndham, Western Australia (19 July 1996)[123] |

−19.6 | −3.3 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (20 July 2010)[124] |

| August | 41.2 | 106.2 |

West Roebuck, Western Australia (23 August 2020)[125] |

−20.6 | −5.1 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (14 August 1968)[126] |

| September | 43.1 | 109.6 |

West Roebuck, Western Australia (27 September 2003)[125] |

−16.7 | 1.9 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (20 September 1967)[127] |

| October | 46.9 | 116.4 |

Port Hedland, Western Australia (22 October 2002)[128] |

−12.0 | 10.4 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (29 October 2006)[129] |

| November | 48.7 | 119.7 |

Birdsville, Queensland (17 November 1990)[130] |

−9.4 | 15.1 |

Charlotte Pass, New South Wales (26 November 1968)[131] |

| December | 49.9 | 121.8 | −9.0 | 15.8 |

Thredbo Ski Resort, New South Wales (13 December 1976)[133] | |

| Climate data for Australia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 50.7 (123.3) |

50.5 (122.9) |

48.1 (118.6) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.2 (106.2) |

43.1 (109.6) |

46.9 (116.4) |

48.7 (119.7) |

49.9 (121.8) |

50.7 (123.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.7 (18.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government[134] | |||||||||||||

Natural hazards and disasters

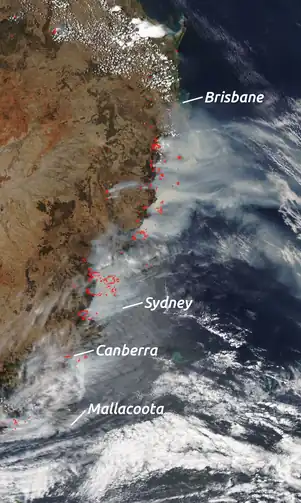

Bushfires

Climatic factors contribute to Australia's high incidence of bushfires, particularly during the summer months. Low relative humidity, wind and lack of rain can cause a small fire, either man-made or caused by lightning strikes, to spread rapidly. Low humidity, the heat of the sun and lack of water cause vegetation to dry out becoming a perfect fuel for the fire. High winds fan the flames, increasing their intensity and the speed and distance at which they can travel.[135]

Many of the worst bushfires in eastern Australia, such as the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires, accompany El Niño–Southern Oscillation events which tend to cause a warm, dry and windy climate.[136]

The worst bushfires in Australian history occurred during the 2019–2020 Australian bushfire season, also known as the "Black Summer", which lasted for 6 months and burnt 140,000 km2 (55,000 mi2) of land primarily in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory. By the end of the season there had been 14-34 direct human deaths, hundreds of indirect human deaths, 1-3 billion animal deaths and 3,500 homes destroyed.[137][138]

Prior to this, the worst had been the Black Saturday fires in February to March 2009, causing 173 deaths and destroying over 2000 homes in Victoria.[139]

Flooding

Though most of Australia is arid or semi-arid, some regions have very significant rainfall. The Wet Tropics in northeast Queensland as well as the western half of Tasmania both average over 1400mm (55 in) of rainfall annually, sometimes much higher. As a result, the former has some of Australia's only tropical rainforest, while the latter features extensive temperate rainforests where floods can occur at any time.

Through La Niña years the eastern seaboard of Australia (east of the Great Dividing Range) records above-average rainfall, usually creating damaging floods. The 2010–2011 La Niña system broke many rainfall records in Australia, particularly in the states of Queensland and New South Wales, with extensive flooding and major damage to infrastructure and crops. The central east area of Queensland, an area the size of Germany and France combined, was under water in 2010–11. La Nina related flooding has affected major eastern cities such as Sydney, and especially Brisbane. The 2022 eastern Australia floods were also one of the worst recorded flood events.

West of the Great Dividing Range, higher than average rainfall may be related to a negative Indian Ocean Dipole, which sometimes leads to inland flooding, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin river system and its flood plains and especially during winter.

The Top End, Kimberley and much of North and Far North Queensland are affected by the Australian monsoon (wet season) which brings heavy rain, thunderstorms, tropical cyclones (see below) and frequent flooding from November to April, making many unsealed roads impassable for part of the year. As a result, these regions are feature extensive tropical savannah.

Drought

Drought in Australia is defined by rainfall over a three-month period being in the lowest ten per cent of amounts having been recorded for that region in the past.[140] This definition takes into account that low rainfall is a relative term and rainfall deficiencies need to be compared to typical rainfall patterns including seasonal variations. Specifically drought in Australia is defined in relation to a rainfall deficiency of pastoral leases and is determined by decile analysis applied to a certain area.[141]

Historical climatic records are now sufficiently reliable to profile climate variability taking into account expectations for regions.[142] State Governments are responsible for declaring a region drought affected and the declaration will take into account factors other than rainfall.[140]

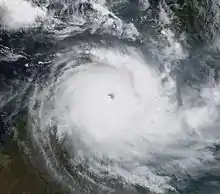

Tropical cyclones

Australia is affected by tropical cyclones which primarily occur between December and April but have occasionally developed in November and May.[143] Cyclones over mainland Australia occur on average five to six times each year.[91] The regions between Broome and Exmouth are most prone to cyclones.[144] Tropical cyclones are known to bring destructive winds, heavy rain with flooding creating storm surges along the coast, causing inundation to low-lying areas. The strongest Australian region cyclone was 2006's Cyclone Monica, with gusts topping 350 km/h (220 mph). Cyclones can also move inland, decaying to rain depressions, dumping heavy rain and causing flooding.[145]

The worst cyclones of Australia have caused billions of dollars of damage and many deaths. Cyclone Tracy crossed directly over Darwin in 1974, killing 71 persons. It was Australia's most damaging cyclone.[146] Cyclone Mahina in 1899 brought a storm surge to Far North Queensland reaching 13 metres (43 ft) high, causing 400 deaths and making it the worst natural disaster to befall Australia.[147] Cyclone Larry struck North Queensland and passed over Innisfail in 2006 causing damages estimated at A$1.5 billion. However, there were no deaths in that storm. Cyclone Yasi caused severe flooding and had a total estimated cost of A$3.5 billion making it the second-most costliest cyclone to strike Australia.[146]

Blizzards

Blizzards are not common in mainland Australia, but occur frequently in the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales and Victoria. When blizzards do occur, they can affect the Tasmanian Highlands and, particularly, Mount Wellington, which towers over the Tasmanian capital Hobart. Blizzards do not affect any major towns or cities, because there are no populated areas located in the mountains except for the ski resort towns of New South Wales and Victoria.

Dust storms

A dust storm or sandstorm, a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions, arises when a gust front passes or when the wind force exceeds the threshold value where loose sand and dust are removed from the dry surface. Particles are transported by saltation and suspension, causing soil erosion from one place and deposition in another.

Sandstorm usually refers to dust storms in desert areas when, in addition to fine particles obscuring visibility, a considerable amount of larger sand particles moves closer to the surface. The term dust storm is more likely to be used when finer particles are blown long distances, especially when the dust storm affects urban areas.

Climate change

Climate change in Australia has been a critical issue since the beginning of the 21st century. Australia is becoming hotter and more prone to extreme heat, bushfires, droughts, floods, and longer fire seasons because of climate change. Climate issues include wildfires, heatwaves, cyclones, rising sea-levels, and erosion.[149][150][151]

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Australia has experienced an increase of over 1.4 °C in average annual temperatures,[152] with warming occurring at twice the rate over the past 50 years compared with the previous 50 years.[153] Recent climate events such as extremely high temperatures and widespread drought have focused government and public attention on the effects of climate change in Australia.[154] Rainfall in southwestern Australia has decreased by 10–20% since the 1970s, while southeastern Australia has also experienced a moderate decline since the 1990s. Rainfall is expected to become heavier and more infrequent, as well as more common in summer rather than in winter. Australia's annual average temperatures are projected to increase 0.4–2.0 °C above 1990 levels by the year 2030, and 1–6 °C by 2070. Average precipitation in the southwest and southeast Australia is projected to decline during this time, while regions such as the northwest may experience increases in rainfall.

Climate change is affecting the continent's environment and ecosystems. Australia is vulnerable to the effects of global warming projected for the next 50 to 100 years because of its extensive arid and semi-arid areas, and already warm climate, high annual rainfall variability. The continent's high fire risk increases this susceptibility to changes in temperature and climate. Meanwhile, Australia's coastlines will experience erosion and inundation from an estimated 8–88 cm increase in global sea level. Australia's unique ecosystems such as the Great Barrier Reef and many animal species are also at risk.

Climate change also has diverse implications for Australia's economy, agriculture and public health.[155] Projected impacts include more severe floods, droughts, and cyclones.[156] Furthermore, Australia's population is highly concentrated in coastal areas at risk from rising sea levels, and existing pressures on water supply will be exacerbated. The exposure of Indigenous Australians to climate change impacts is exacerbated by existing socio-economic disadvantages which are linked to colonial and post-colonial marginalisation.[149] The communities most affected by climate changes are those in the North where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 30% of the population.[157] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities located in the coastal north are the most disadvantaged due to social and economic issues and their reliance on traditional land for food, culture, and health. This has raised the question for many community members in these areas, "Should we stay or move away?"[157]

Australia is also a contributor to climate change, with its greenhouse gas emissions per capita above the world average. The country is highly reliant on coal and other fossil fuels, although renewable energy coverage is increasing. National mitigation efforts include a commitment to achieving net zero emissions by 2050 under the Paris Agreement, although Australia has repeatedly ranked poorly in the Climate Change Performance Index and other international rankings for its climate targets and implementation. Adaptation can be performed at national and local levels[158] and was identified as a priority for Australia in the 2007 Garnaut Review.

Climate change has been a divisive or politicised issue in Australian politics since the 2000s, which has contributed to successive governments implementing and repealing climate change policies, such as carbon pricing. Some Australian media outlets have promoted climate misinformation. The issue has sparked protests in support of climate change policies, including some of the largest demonstrations in Australia's history.See also

- Indigenous Australian seasons

- List of wettest known tropical cyclones in Australia

- Weather extremes in Australia, an index of extreme Australian weather articles

- Effects of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation in Australia

- Australian monsoon

References

- Scientists Trace Extreme Heat in Australia to Climate Change Archived 4 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine 29 September 2014 NYT

- "State of the Climate 2014". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "CSIRO report says Australia getting hotter with more to come". ABC Online. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ""Stats" (Australian Government)". Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Climate of Australia

- Precipitation in Australia. 1997. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-415-12519-2. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Canberra: Climate and water". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Territory, Bureau of Meteorology Australian Capital (3 January 2020). "Untitled". @BOM_ACT. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

Canberra has reached 43.6C—a new hottest temperature record for any month. The previous Canberra records are 42.2C at Canberra Airport in 1968 and 42.8C at the now-closed Acton site in 1939.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002 Yearbook of Australia Archived 12 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- Southerly Busters Explained Archived 17 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Jason J. Sharples, Graham A. Mills, Richard H. D. McRae, and Rodney O. Weber. "Foehn-Like Winds and Elevated Fire Danger Conditions in Southeastern Australia". Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology (BOM). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "Armidale Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 6 May 1999. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Broken Hill Airport Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 31 August 2004. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Coffs Harbour Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 7 May 1999. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Orange Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Penrith Lakes Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Sydney (Observatory Hill) Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Wagga Wagga Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Wollongong Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Summary statistics Darwin Airport". BOM. 15 July 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 1998. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- "Summary statistics Alice Springs Airport". BOM. 16 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- "CHAPTER 7: Introduction to the Atmosphere". physicalgeography.net. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- BOM – Climate of Queensland

- BOM – Australian climatic zones

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Brisbane Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Cairns Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Gold CoastClimate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Mackay Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Mt Isa Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Rockhampton Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Toowoomba Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Townsville Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Atlas of South Australia | Climate and Weather". Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- "Adelaide Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Mount Gambier Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Oodnadatta Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Port Augusta Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Whyalla Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate of Launceston". BOM. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- McIntyre, Damian (7 August 2020). "Liawenee in Tasmania's Central Highlands breaks record for coldest temperature in island state". ABC News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Devonport Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Hobart Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Launceston Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Strahan Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 23 November 2004. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Hopetoun sizzles as Mildura sweats Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "City swelters, records tumble in heat". The Age. Melbourne. 7 February 2009. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- "Bairnsdale Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Ballarat Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Bendigo Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Melbourne Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Mildura Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Shepparton Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Warrnambool Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Climate of Western Australia". BOM. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Miller G, Mangan J, Pollard D, Thompson S, Felzer B, et al. (2005) Sensitivity of the Australian Monsoon to insolation and vegetation: Implications for human impact on continental moisture balance. Archived 4 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine Geology: Vol. 33, No. 1 pp. 65–68

- Snow in Western Australia: About Snow in WA Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- "Albany Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Broome Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 30 January 1998. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Geraldton Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Kalgoorlie Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Karratha Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Perth Climate Statistics". BOM. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Climate statistics for Australian locations". bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Roaring Forties' shift south means more droughts for southern Australia Archived 31 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine by Helen Davidson from The Guardian. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Loffler, Ernst; Anneliese Loffler; A. J. Rose; Denis Warner (1983). Australia: Portrait of a continent. Richmond, Victoria: Hutchinson Group (Australia). pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-09-130460-7.

- Rain. 1997. ISBN 9780415125192. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia No.50-1964, p. 48

- Kuleshow, Y; de Hoedt, G; Wright, W; Brewster, A (2002). "Thunderstorm distribution and frequency in Australia" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. 51 (3): 148. ISSN 0004-9743. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Indian Ocean". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Northwest cloudbands". Bureau of Meteorology. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records". Climate Extremes. BOM. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- "Climate Statistics for Babinda, QL". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Australia – Climate of Our Continent

- "Trentham snowy days (Woods Point, elevation 698 metres)". AustralianWeatherNews. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- "Nimmitabel snowy days". AustralianWeatherNews. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- "Bendoc and Aberfeldy snowy days". AustralianWeatherNews. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- Heavy snow in southern Australia Archived 20 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 10 August 2005.

- Archived 10 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 5 June 2014

- ""Statistics" Australian gov't". Archived from the original on 30 April 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ""Statistics" Australian Gov't". Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "BOM - Australian Climate Extremes". www.bom.gov.au. Archived from the original on 11 December 2000. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- "Australian daily extremes tables". Bureau of Meteorology. Commonwealth of Australia. 2021. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- "Official records for Australia in July". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Australian Daily Extremes Tables. BOM. 11 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Birch, Laura (13 January 2022). "Onslow in the Pilbara reaches 50.7C, equalling Australia's hottest day on record". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Australian daily extremes tables". Bureau of Meteorology. Commonwealth of Australia. 2021. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 September 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 23 August 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Official records for Australia in December". Daily Extremes. BOM. 22 December 2019. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. BOM. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government

- Weather and Fire Archived 20 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BOM. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- Australian Climate Extremes – Fire Archived 7 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BOM. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- "'Extraordinary' 2019 ends with deadliest day of the worst fire season". Sydney Morning Herald. 1 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- "Australia fires: Life during and after the worst bushfires in history". BBC. 28 April 2020. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- "Police: Australian fires create 'a holocaust'". CNN. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- "Drought". Climate Glossary. BOM. 2006. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- Tapper, Nigel. & Hurry, Lynn. (1993) Australia's Weather Patterns: An Introductory Guide. pp. 51–57. Dellasta. ISBN 1-875627-14-6

- "Our Natural Resources at a Glance – Climate". Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (Australia). 2006. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006. Retrieved 13 November 2006.

- "When is the cyclone season?". BOM. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- "What is the most cyclone-prone region in Australia?". BOM. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- "Surviving Cyclones". BOM. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 May 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2007.

- "Cyclone Yasi to cost insurers $3.5 bln – forecaster". 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "Australia's worst natural disasters". SBS World News Australia. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- Foley, Mike (26 November 2021). "CSIRO study proves climate change driving Australia's 800% boom in bushfires". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Green, Donna (November 2006). "Climate Change and Health: Impacts on Remote Indigenous Communities in Northern Australia". Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. S2CID 131620899.

- Nursey-Bray, Melissa; Palmer, R.; Smith, T. F.; Rist, P. (4 May 2019). "Old ways for new days: Australian Indigenous peoples and climate change". Local Environment. 24 (5): 473–486. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1590325. ISSN 1354-9839.

- Ford, James D. (July 2012). "Indigenous Health and Climate Change". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (7): 1260–1266. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3477984. PMID 22594718.

- "Australia's changing climate".

- Lindenmayer, David; Dovers, Stephen; Morton, Steve, eds. (2014). Ten Commitments Revisited. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4863-0167-6.

- Johnston, Tim (3 October 2007). "Climate change becomes urgent security issue in Australia". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- Preston, B. L.; Jones, R. N. (2006). Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A consultancy report for the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change (PDF). CSIRO.

- Perkins, Miki (13 November 2020). "Climate change is already here: major scientific report". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Zander, Kerstin K.; Petheram, Lisa; Garnett, Stephen T. (1 June 2013). "Stay or leave? Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia". Natural Hazards. 67 (2): 591–609. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0591-4. ISSN 1573-0840. S2CID 128543022.