Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος, Kōnstantînos Dragásēs Palaiológos; 8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453) was the last Roman (Byzantine) emperor, reigning from 1449 until his death in battle at the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Constantine's death marked the definitive end of the Eastern Roman Empire, which traced its origin to Constantine the Great's foundation of Constantinople as the Roman Empire's new capital in 330.

| Constantine XI Palaiologos | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |||||

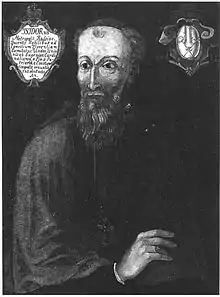

.png.webp) 15th-century portrait of Constantine XI (from a 15th-century codex containing a copy of the Extracts of History by Joannes Zonaras) | |||||

| Byzantine emperor | |||||

| Reign | 6 January 1449[lower-alpha 1] – 29 May 1453 | ||||

| Predecessor | John VIII Palaiologos | ||||

| Despot of the Morea | |||||

| Reign | 1 May 1428 – March 1449[lower-alpha 2] | ||||

| Predecessor | Theodore II Palaiologos (alone) | ||||

| Successor | Demetrios and Thomas Palaiologos | ||||

| Co-rulers | Theodore II Palaiologos (1428–1443) Thomas Palaiologos (1428–1449) | ||||

| Born | 8 February 1405 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire | ||||

| Died | 29 May 1453 (aged 48) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Palaiologos | ||||

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos | ||||

| Mother | Helena Dragaš | ||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox | ||||

| Signature | |||||

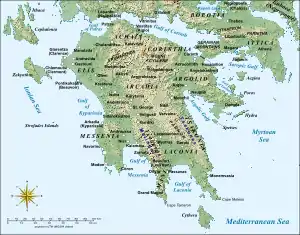

Constantine was the fourth son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and Helena Dragaš, the daughter of Serbian ruler Konstantin Dejanović. Little is known of his early life, but from the 1420s onward, he is repeatedly demonstrated to have been a skilled general. Based on his career and surviving contemporary sources, Constantine appears to have been primarily a soldier. This does not mean that Constantine was not also a skilled administrator: he was trusted and favored to such an extent by his older brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, that he was designated as regent twice during John VIII's journeys away from Constantinople in 1423–1424 and 1437–1440. In 1427–1428, Constantine and John fended off an attack on the Morea (the Peloponnese) by Carlo I Tocco, ruler of Epirus, and in 1428 Constantine was proclaimed Despot of the Morea and ruled the province together with his older brother Theodore and his younger brother Thomas. Together, they extended Roman rule to cover almost the entire Peloponnese for the first time since the Fourth Crusade more than two hundred years before and rebuilt the ancient Hexamilion wall, which defended the peninsula from outside attacks. Although ultimately unsuccessful, Constantine personally led a campaign into Central Greece and Thessaly in 1444–1446, attempting to extend Byzantine rule into Greece once more.

In October 1448, John VIII died without children, and as his favored successor, Constantine was proclaimed emperor on 6 January 1449. Constantine's brief reign would see the emperor grapple with three primary concerns. First, there was the issue of an heir, as Constantine was also childless. Despite attempts by Constantine's friend and confidant George Sphrantzes to find him a wife, Constantine ultimately died unmarried. The second concern was the religious disunity within what little remained of his empire. Constantine and his predecessor John VIII both believed a union between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches was needed to secure military aid from Catholic Europe, but much of the Roman populace opposed the idea. Finally, the most important concern was the growing Ottoman Empire, which by 1449 completely surrounded Constantinople. In April 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II laid siege to Constantinople with an army perhaps numbering as many as 80,000 men. Even though the city's defenders may have numbered less than a tenth of the sultan's army, Constantine considered the idea of abandoning Constantinople unthinkable. The emperor stayed to defend the city and on 29 May, Constantinople fell. Constantine died the same day. Although no reliable eyewitness accounts of his death survived, most historical accounts agree that the emperor led a last charge against the Ottomans and died fighting.

Constantine was the last Christian ruler of Constantinople, which alongside his bravery at the city's fall cemented him as a near-legendary figure in later histories and Greek folklore. Some saw the foundation of Constantinople (the New Rome) under Constantine the Great and its loss under another Constantine as fulfillment of the city's destiny, just as Old Rome had been founded by a Romulus and lost under another, Romulus Augustulus. He became known in later Greek folklore as the Marble Emperor (Greek: Μαρμαρωμένος Βασιλεύς, romanized: Marmaromenos Vasilias, lit. 'Emperor/King turned into Marble'), reflecting a popular legend that Constantine had not actually died, but had been rescued by an angel and turned into marble, hidden beneath the Golden Gate of Constantinople awaiting a call from God to be restored to life and reconquer both the city and the old empire.

Early life

Family and background

Constantine Dragases Palaiologos was born on 8 February 1405[lower-alpha 3] as the fourth son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391–1425), the eighth emperor of the Palaiologos dynasty.[4] Constantine's mother (from whom he took his second last name) was Helena Dragaš, member of the powerful House of Dragaš and daughter of Serbian ruler Konstantin Dejanović. Constantine is frequently described as Porphyrogénnētos ("born in the purple"), a distinction granted to sons born to a reigning emperor in the imperial palace.[5]

Manuel ruled a disintegrating and dwindling Byzantine Empire.[4] The catalyst of Byzantium's fall had been the arrival of the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia in the 11th century. Though some emperors, such as Alexios I and Manuel I, had successfully recovered portions of Anatolia through help from western crusaders, their gains were only temporary. Anatolia was the empire's most fertile, populated, and wealthy region, and after its loss, Byzantium more or less experienced constant decline. Although most of it was eventually reconquered, the Byzantine Empire was crippled by the 1204 Fourth Crusade and the loss of Constantinople to the Latin Empire, formed by the crusaders. The Byzantine Empire, under the founder of the Palaiologos dynasty, Michael VIII, retook Constantinople in 1261, though the damage to the empire was irreversible and the empire continued to decline over the course of the 14th century as the result of frequent civil wars.[6] Over the course of the 14th century, the Ottoman Turks had conquered vast swaths of territories and by 1405, they ruled much of Anatolia, Bulgaria, central Greece, Macedonia, Serbia and Thessaly. The Byzantine Empire, once extending throughout the eastern Mediterranean, was reduced to the imperial capital of Constantinople, the Peloponnese, and a handful of islands in the Aegean Sea, and was also forced to pay tribute to the Ottomans.[4]

As the empire dwindled, the emperors concluded that the only way to ensure that their remaining territory was kept intact was to grant some of their holdings to their sons, who received the title of despot, as appanages to defend and govern. Manuel's oldest son, John, was raised to co-emperor and designated to succeed his father. The second son, Theodore, was designated as the Despot of the Morea (the prosperous province constituting the Peloponnese) and the third son, Andronikos, was proclaimed as Despot of Thessaloniki in 1408. The younger sons; Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas, were kept in Constantinople as there was not sufficient land left to grant them.[7]

Little is known of Constantine's early life. From an early age, he was admired by George Sphrantzes (later a famed Byzantine historian), who would later enter his service, and later encomiasts often wrote that Constantine had always been courageous, adventurous, and skilled in martial arts, horsemanship, and hunting.[5] Many accounts of Constantine's life, both before and after he became emperor, are heavily skewed and eulogize his reign, as most of them lack contemporary sources and were composed after his death.[8] Based on his actions and the surviving commentary from some of his advisors and contemporaries, Constantine appeared to have been more comfortable with military matters than with matters of state or diplomacy, though he was also a competent administrator—as illustrated by his tenures as regent—and tended to heed his councilors' advice on important matters of state.[9] Aside from stylized and smudged depictions on seals and coins, no contemporary depictions of Constantine survive.[10] Notable images of Constantine include a seal currently located in Vienna (of unknown provenance, probably from an imperial chrysobull), a few coins, and his portrait among the other Byzantine emperors in the Biblioteca Estense copy of the history of Zonaras. In the latter he is shown with a rounded beard, in noted contrast to his forked-bearded relatives, but it is unclear whether that reflects his actual appearance.[11]

Early career

_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg.webp)

After an unsuccessful Ottoman siege of Constantinople in 1422, Manuel II suffered a stroke and was left paralyzed in one side of his body. He lived for another three years, but the empire's government was effectively in the hands of Constantine's brother John. Thessaloniki was also under siege by the Ottomans; to prevent it from falling into their hands, John gave the city to the Republic of Venice. As Manuel II had once hoped years ago, John hoped to rally support from Western Europe, and he left Constantinople in November 1423 to travel to Venice and Hungary.[12] By this time, Manuel had abandoned his hope of western aid and had even attempted to dissuade John from pursuing it. Manuel believed that an eventual church union, which would become John's goal, would only antagonize the Turks and the empire's populace, which could have started a civil war.[13]

John was impressed by his brother's actions during the 1422 Ottoman siege,[3] and trusted him more than his other brothers. Constantine was given the title of despot and was left to rule Constantinople as regent. With the aid of his bedridden father Manuel, Constantine drew up a new peace treaty with the Ottoman sultan Murad II, who momentarily spared Constantinople from further Turkish attacks. John returned from his journey in November 1424 after failing to procure help. On 21 July 1425, Manuel died and John became the senior emperor, John VIII Palaiologos. Constantine was granted a strip of land to the north of Constantinople that extended from the town of Mesembria in the north to Derkos in the south. It also included the port of Selymbria as his appanage in 1425.[12] Although this strip of land was small, it was close to Constantinople and strategically important, which demonstrated that Constantine was trusted by both Manuel II and John.[9]

After Constantine's successful tenure as regent, John deemed his brother loyal and capable. Because their brother Theodore expressed his discontent over his position as Despot of the Morea to John during the latter's visit in 1423, John soon recalled Constantine from Mesembria and designated him as Theodore's successor. Theodore eventually changed his mind, but John would eventually assign Constantine to the Morea as a despot in 1427 after a campaign there. Though Theodore was content to rule in the Morea, historian Donald Nicol believes that the support was helpful, as the peninsula was repeatedly threatened by external forces throughout the 1420s. In 1423, the Ottomans broke through the ancient Hexamilion wall—which guarded the Peloponnese—and devastated the Morea. The Morea was also constantly threatened by Carlo I Tocco, the Italian ruler of Epirus, who campaigned against Theodore shortly before the Ottoman invasion and again in 1426, occupying territory in the northwestern parts of the Morea.[14]

In 1427, John VIII personally set out to deal with Tocco, bringing Constantine and Sphrantzes with him. On 26 December 1427, the two brothers reached Mystras, the capital of the Morea, and made their way to the town of Glarentza, which was captured by the Epirotes. In the Battle of the Echinades, a naval skirmish off the coast of Glarentza, Tocco was defeated and he agreed to relinquish his conquests in the Morea. In order to seal the peace, Tocco offered his niece, Maddalena Tocco (whose name was later changed to the Greek Theodora), in marriage to Constantine, her dowry being Glarentza and the other Moreot territories. Glarentza was given to the Byzantines on 1 May 1428 and on 1 July, Constantine married Theodora.[15][16]

Despot of the Morea

Early rule in the Morea

The transfer of Tocco's conquered Moreot territories to Constantine complicated the Morea's government structure. Since his brother Theodore refused to step down as despot, the despotate became governed by two members of the imperial family for the first time since its creation in 1349. Soon thereafter, the younger Thomas (aged 19) was also appointed as a third Despot of the Morea, which meant that the nominally undivided despotate had effectively disintegrated into three smaller principalities. Theodore did not share control over Mystras with Constantine or Thomas; instead, Theodore granted Constantine lands throughout the Morea, including the northern harbor town of Aigio, fortresses and towns in Laconia (in the south), and Kalamata and Messenia in the west. Constantine made Glarentza, which he was entitled to by marriage, his capital. Meanwhile, Thomas was given lands in the north and based himself in the castle of Kalavryta.[17] During his tenure as despot, Constantine was brave and energetic, but generally cautious.[1] Shortly after being appointed as despots, Constantine and Thomas, together with Theodore, joined forces in an attempt to seize the flourishing and strategically-important port of Patras in the northwest of the Morea, which was ruled by its Catholic Archbishop, Pandolfo Malatesta (Theodore's brother-in-law). The campaign ended in failure, possibly due to Theodore's reluctant participation and Thomas' inexperience. Constantine confided with Sphrantzes and John at a secret meeting in Mystras that he would make a second attempt to retake Patras by himself; if he failed, he would return to his old appanage by the Black Sea. Constantine and Sphrantzes, confident that the city's many Greek inhabitants would support their takeover, marched towards Patras on 1 March 1429, and they besieged the city on 20 March. The siege developed into a long and drawn-out engagement, with occasional skirmishes. At one point, Constantine's horse was shot and killed under him and the despot nearly died, being saved by Sphrantzes at the cost of Sphrantzes being captured by the defenders of Patras (though he would be released, albeit in a state of near-death, on 23 April). After almost two months, the defenders opened up to the possibility of negotiation in May. Malatesta journeyed to Italy in an attempt to recruit reinforcements and the defenders agreed that if he did not return to them by the end of the month, Patras would surrender. Constantine agreed to this and withdrew his army. On 1 June, Constantine returned to the city and, since the Archbishop had not returned, met with the city's leaders in the city's Cathedral of St. Andrew on 4 June and they accepted him as their new lord. The Archbishop's castle, located on a nearby hill, held out against Constantine for another 12 months before surrendering.[18]

Constantine's capture of Patras was seen as an affront by the Pope, the Venetians, and the Ottomans. In order to pacify any threats, Constantine sent ambassadors to all three, with Sphrantzes being sent to talk with Turahan, the Ottoman governor of Thessaly. Although Sphrantzes was successful in removing the threat of Turkish reprisal, the threat from the west was realized as the dispossessed Archbishop arrived at the head of a mercenary army of Catalans. Unfortunately for Malatesta, the Catalans had little interest in helping him recover Patras, and they attacked and seized Glarentza instead, which Constantine had to buy back from them for 6,000 Venetian ducats, and began plundering the Moreot coastline. To prevent Glarentza from being seized by pirates, Constantine eventually ordered it to be destroyed.[19] During this perilous time, Constantine suffered another loss: Theodora died in November 1429. The grief-stricken Constantine first had her buried at Glarentza, but then moved to Mystras.[20] Once the Archbishop's castle surrendered to Constantine in July 1430, the city was fully restored to Byzantine rule after 225 years of foreign occupation. In November, Sphrantzes was rewarded by being proclaimed as the city's governor.[19]

By the early 1430s, the efforts of Constantine and his younger brother Thomas had ensured that nearly all of the Peloponnese was under Byzantine rule again since the Fourth Crusade. Thomas ended the Principality of Achaea by marrying Catherine Zaccaria, daughter and heir of the final prince, Centurione II Zaccaria. When Centurione died in 1432, Thomas took control of all his remaining territories by right of marriage. The only lands in the Peloponnese remaining under foreign rule were the few port towns and cities still held by the Republic of Venice. Sultan Murad II felt uneasy about the recent string of Byzantine successes in the Morea. In 1431, Turahan sent his troops south on Murad's orders to demolish the Hexamilion wall in an effort to remind the despots that they were the Sultan's vassals.[21]

Second tenure as regent

In March 1432, Constantine, possibly desiring to be closer to Mystras, made a new territorial agreement (presumably approved by Theodore and John VIII) with Thomas. Thomas agreed to cede his fortress Kalavryta to Constantine, who made it his new capital, in exchange for Elis, which Thomas made his new capital.[22] Relationships between the three despots eventually soured. John VIII had no sons to succeed him and it was thus assumed that his successor would be one of his four surviving brothers (Andronikos having died some time before). John VIII's preferred successor was known to be Constantine and though this choice was accepted by Thomas, who had a good relationship with his older brother, it was resented by Constantine's older brother Theodore. When Constantine was summoned to the capital in 1435, Theodore falsely believed it was to appoint Constantine as co-emperor and designated heir, and he travelled to Constantinople to raise his objections. The quarrel between Constantine and Theodore was not resolved until the end of 1436, when the future Patriarch Gregory Mammas was sent to reconcile them and prevent civil war. The brothers agreed that Constantine was to return to Constantinople, while Theodore and Thomas would remain in the Morea. John needed Constantine in Constantinople as he was departing for Italy soon. On 24 September 1437, Constantine reached Constantinople. Although he was not proclaimed as co-emperor,[20] his appointment as regent for a second time, suggested to John by their mother Helena,[16] indicated that he was to be regarded as John's intended heir,[20] much to the dismay of his other brothers.[16]

John left for Italy in November to attend the Council of Ferrara in an effort to unite the Eastern and Western churches. Although many in the Byzantine Empire opposed a union of the Churches, as it would mean religious submission under the Papacy, John viewed a union as necessary. The papacy did not view the situation of the Christians in the East as something positive, but it would not call for any aid to the disintegrating empire if it did not acknowledge obedience to the Catholic Church and renounce what Catholics perceived as errors. John brought a large delegation to Italy, including Joseph II, the Patriarch of Constantinople; representatives of the Patriarchs of Alexandria and Jerusalem; large numbers of bishops, monks, and priests; and his younger brother Demetrios. Demetrios showed opposition against a church union, but John decided not to leave him in the East since Demetrios had shown rebellious tendencies and was thought to try to take the throne with Ottoman support. Constantine was not left without supporting courtiers in Constantinople: Constantine's and John's cousin Demetrios Palaiologos Kantakouzenos and the experienced statesman Loukas Notaras were left in the city. Helena and Sphrantzes were also there to advise Constantine.[23] In 1438, Constantine served as the best man at Sphrantzes' wedding,[23] and would later become the godfather to two of Sphrantzes' children.[24]

During John's absence from Constantinople, the Ottomans abided by the previously established peace. Trouble appeared to have brewed only once: in early 1439, Constantine wrote to his brother in Italy to remind the Pope that the Byzantines had been promised two warships by the end of spring. Constantine hoped that the ships would leave Italy within fifteen days, as he believed that Murad II was planning a strong offensive against Constantinople. Although the ships were not sent, Constantinople was not in danger as Murad's campaign focused on taking Smederevo in Serbia.[25]

In June 1439, the council in Florence, Italy, declared that the churches had been reunited. John returned to Constantinople on 1 February 1440. Although he was received with a grand ceremony organized by Constantine and Demetrios (who had returned sometime earlier), the news of the unification stirred a wave of resentment and bitterness among the general populace,[26] who felt that John had betrayed their faith and their world view.[27] Many feared the union would arouse suspicion among the Ottomans.[26] Constantine's agreed with his brother's views on the union: if a sacrifice of the independence of their church resulted in the Westerners organizing a crusade and saving Constantinople, it would not have been in vain.[26]

Second marriage and Ottoman threats

Despite having been relieved of his duties as regent upon John's return, Constantine stayed in the capital for the rest of 1440. He may have stayed in order to find a suitable wife, wishing to remarry since it had been more than ten years since Theodora's death. He decided on Caterina Gattilusio, daughter of Dorino I Gattilusio, the Genoese lord of the island Lesbos. Sphrantzes was sent to Lesbos in December 1440 to propose and arrange the marriage. In late 1441, Constantine sailed to Lesbos with Sphrantzes and Loukas Notaras, and in August he married Caterina. In September, he left Lesbos, leaving Caterina with her father on Lesbos, to travel to the Morea.[28]

Upon his return to the Morea, Constantine observed that Theodore and Thomas had ruled well without him. He believed that he could serve the empire's needs better if he was closer to the capital. His younger brother Demetrios governed Constantine's former appanage around Mesembria in Thrace, and Constantine pondered the possibility that he and Demetrios could switch places, with Constantine regaining the Black Sea appanage and Demetrios being granted Constantine's holdings in the Morea. Constantine sent Sphrantzes to propose the idea to both Demetrios and Murad II, who by this point had to be consulted about any appointments.[29]

By 1442, Demetrios had no desire for new appointments and was eyeing the imperial throne. He had just made a deal with Murad himself and raised an army, portraying himself as the champion of the Turk-supported cause that opposed the union of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches and declared war on John. When Sphrantzes reached Demetrios to forward Constantine's offer, Demetrios was already preparing to march on Constantinople. The danger he posed to the city was so great that Constantine was summoned from the Morea by John to oversee the city's defenses. In April 1442, Demetrios and the Ottomans began their attack and in July, Constantine left the Morea to relieve his brother in the capital. On the way, Constantine met his wife at Lesbos and together they sailed to Lemnos, where they were stopped by an Ottoman blockade and were trapped for months. Although Venice sent ships to assist them, Caterina fell ill and died in August; she was buried at Myrina on Lemnos. Constantine did not reach Constantinople until November and by then, the Ottoman attack had already been repelled.[30] Demetrios' punishment was a brief imprisonment.[31] In March 1443, Sphrantzes was made governor of Selymbria in Constantine's name. From Selymbria, Sphrantzes and Constantine were able to keep a watchful eye on Demetrios' activities. In November, Constantine relinquished control of Selymbria to Theodore, who had abandoned his position as Despot of the Morea, which made Constantine and Thomas the sole Despots of the Morea and gave Constantine Mystras, the despotate's prosperous capital.[32]

Despot at Mystras

With Theodore and Demetrios gone, Constantine and Thomas hoped to strengthen the Morea. By this time, the Morea was the cultural center of the Byzantine world and provided a more hopeful atmosphere than Constantinople. Patrons of art and science had settled there at Theodore's invitation and churches, monasteries, and mansions continued to be built. The two Palaiologos brothers hoped to make the Morea into a safe and nearly self-sufficient principality. The philosopher Gemistus Pletho, employed in Constantine's service, said that while Constantinople had once been the New Rome, Mystras and the Morea could become the "New Sparta", a centralized and strong Hellenic kingdom in its own right.[33]

One of the projects of the brothers' plan to strengthen the despotate was the reconstruction of the Hexamilion wall, which was destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall by March 1444. The project impressed many of their subjects and contemporaries, including the Venetian lords in the Peloponnese, who had politely declined to help with its funding. The restoration had cost much in both money and manpower; many of the Moreot landowners had momentarily fled to Venetian lands to avoid financing the venture while others had rebelled before being compelled through military means.[34] Constantine attempted to attract the loyalty of the Moreot landowners by granting them both further lands and various privileges. He also staged local athletic games, where young Moreots could run races for prizes.[35]

In the summer of 1444, perhaps encouraged by news from the west that a crusade had set out from Hungary in 1443, Constantine invaded the Latin Duchy of Athens, his direct northern neighbor and an Ottoman vassal. Through Sphrantzes, Constantine was in contact with Cardinal Julian Cesarini, who along with Władysław III of Poland and Hungary was one of the leaders of the crusade. Cesarini was made aware of Constantine's intentions and that he was ready to aid the crusade in striking at the Ottomans from the south. Constantine swiftly captured Athens and Thebes, which forced Duke Nerio II Acciaioli to pay the tribute to him instead of the Ottomans. The recapture of Athens was seen as a particularly glorious feat. One of Constantine's counsellors compared the despot to the legendary ancient Athenian general Themistocles. Although the crusading army was destroyed by the Ottoman army led by Murad II at the Battle of Varna on 10 November 1444, Constantine was not deterred. His initial campaign had been remarkably successful and he had also received foreign support from Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy, who had sent him 300 soldiers. With the Burgundian soldiers and his own men, Constantine raided central Greece as far north as the Pindus mountains in Thessaly, where the locals happily welcomed him as their new lord. As Constantine's campaign progressed, one of his governors, Constantine Kantakouzenos, also made his way north, attacked Thessaly, and seized the town of Lidoriki from the Ottomans. The townspeople were so excited at their liberation that they renamed the town to Kantakouzinopolis in his honor.[36]

Tiring of Constantine's successes, Murad II, accompanied by Duke Nerio II of Athens, marched on the Morea in 1446, with an army possibly numbering as many as 60,000 men.[37] Despite the overwhelming number of Ottoman troops, Constantine refused to surrender his gains in Greece and instead prepared for battle.[38] The Ottomans quickly restored control over Thessaly; Constantine and Thomas rallied at the Hexamilion wall, which the Ottomans reached on 27 November.[37] Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as 20,000 men, to defend it.[39] Although the wall might have held against the great Ottoman army under normal circumstances, Murad had brought cannons with him and by 10 December, the wall had been reduced to rubble and most of the defenders were either killed or captured; Constantine and Thomas barely escaped the catastrophic defeat. Turahan was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese. Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad only wanted to instill terror and did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time. The Turks left the peninsula devastated and depopulated. Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord, pay him tribute, and promise to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.[40]

Reign as emperor

Accession to the throne

Theodore, once Despot of the Morea, died in June 1448 and on 31 October that same year, John VIII Palaiologos died in Constantinople.[41] Compared to his other living brothers, Constantine was the most popular of the Palaiologoi, both in the Morea and in the capital.[42] It was well known that John's favored successor was Constantine and ultimately, the will of Helena Dragaš (who also preferred Constantine), prevailed in the matter. Both Thomas, who appeared to have had no intention of claiming the throne, and Demetrios, who most certainly did, hurried to Constantinople and reached the capital before Constantine left the Morea. Although many favored Demetrios for his anti-unionist sentiment, Helena reserved her right to act as regent until her eldest son, Constantine arrived, and stalled Demetrios' attempt at seizing the throne. Thomas accepted Constantine's appointment and Demetrios was overruled, though he later proclaimed Constantine as his new emperor.[41] Soon thereafter, Sphrantzes informed Sultan Murad II,[41] who also accepted the appointment on 6 December 1448.[43] With the issue of succession peacefully resolved, Helena sent two envoys, Manuel Palaiologos Iagros and Alexios Philanthropenos Laskaris, to the Morea to proclaim Constantine as emperor and bring him to the capital. Thomas also accompanied them.[41]

In a small civil ceremony at Mystras, possibly in one of the churches or in the Despot's Palace, on 6 January 1449, Constantine was proclaimed Emperor of the Romans. He was not given a crown; instead, Constantine may have put on another type of imperial headgear, a pilos, on his head with his own hands. Although emperors were traditionally crowned in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, there was historical precedent for smaller and local ceremonies: centuries ago, Manuel I Komnenos had been given the title of emperor by his dying father, John II Komnenos, in Cilicia; Constantine's great-grandfather, John VI Kantakouzenos, had been proclaimed emperor at Didymoteicho in Thrace. Both Manuel I and John VI had been careful to perform the traditional coronation ceremony in Constantinople once they reached the capital. In Constantine's case, no such ceremony was ever performed. Both Constantine and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory III Mammas, were supporters of the Union of the Churches: a ceremony in which Gregory crowned Constantine emperor might have led the anti-unionists in the capital to rebel. Constantine's rise to emperor was controversial: although he was accepted on account of his lineage with few alternative candidates, his lack of a full coronation and support for the Union of the Churches damaged public perception of the new emperor.[44]

Careful not to anger the anti-unionists through being crowned by Gregory III, Constantine believed that his proclamation at Mystras had sufficed as an imperial coronation and had given him all the constitutional rights of the one true emperor. In his earliest known imperial document, a chrysobull from February 1449, he refers to himself as "Constantine Palaiologos in Christ true Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans". Constantine arrived at Constantinople on 12 March 1449, having been provided means of travel by a Catalan ship.[45]

Constantine was well prepared for his accession to the throne after serving as regent twice and ruling numerous fiefs throughout the crumbling empire.[9] By Constantine's time, Constantinople was a shadow of its former glory; the city never truly recovered from the 1204 sack by the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade. Instead of the grand imperial capital it once was, 15th century Constantinople was an almost rural network of population centers, with many of the city's churches and palaces, including the former imperial palace, abandoned and in disrepair. Instead of the former imperial palace, the Palaiologoi emperors used the Palace of Blachernae, located considerably closer to the city's walls, as their main residence. The city's population had declined significantly due to the Latin occupation, the 14th century civil wars, and outbreaks of the Black Death in 1347, 1409 and 1410. By the time Constantine became emperor, only about 50,000 people lived in the city.[46]

Initial concerns

One of Constantine's most pressing concerns was the Ottomans. One of his first acts as emperor, just two weeks after arriving in the capital, was to attempt to secure the empire by arranging a truce with Murad II. He sent an ambassador, Andronikos Iagaris, to the sultan. Iagaris was successful, and the agreed-upon truce also included Constantine's brothers in the Morea to secure the province from further Ottoman attacks.[47] In order to remove his rebellious brother Demetrios from the capital and its vicinity, Constantine had made Demetrios his replacement as Despot of the Morea to rule the despotate alongside Thomas. Demetrios was granted Constantine's former capital, Mystras, and given authority over the southern and eastern parts of the despotate, while Thomas ruled the northwest and Corinthia alternating between Patras and Leontari as his place of residence.[2]

Constantine tried to hold numerous discussions with the anti-unionists in the capital, who had organized themselves as a synaxis to oppose Patriarch Gregory III's authority, on account of him being a unionist. Constantine was not a fanatical unionist and merely viewed the Union of the Churches as necessary for the empire's survival. The unionists found this argument to be baseless and materialistic, believing that help would be more likely to come through trust in God than a western crusading campaign.[48]

Another pressing concern was the continuation of the imperial family as neither Constantine nor his brothers had male children at the time. In February 1449, Constantine had sent Manuel Dishypatos as an envoy to Italy to speak with Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples in order to secure military aid against the Ottomans and forge a marriage alliance. The intended match was the daughter of Alfonso's nephew, Beatrice of Coimbra, but the alliance failed. In October 1449, Constantine sent Sphrantzes to the east to visit the Empire of Trebizond and the Kingdom of Georgia and see if there were any suitable brides there. Sphrantzes, accompanied by a large retinue of priests, nobles, musicians and soldiers, left the capital for nearly two years.[49]

While at the court of Emperor John IV Megas Komnenos in Trebizond, Sphrantzes was made aware that Murad II had died. Though John IV saw this as positive news, Sphrantzes was more anxious: the old sultan had grown tired and had given up all hope of conquering Constantinople. His young son and successor, Mehmed II, was ambitious, young and energetic. Sphrantzes had the idea that the sultan could be dissuaded from invading Constantinople if Constantine married Murad II's widow, Mara Branković. Constantine supported the idea when he received Sphrantzes' report in May 1451 and sent envoys to Serbia, where Mara had returned to after Murad II's death.[50] Many of Constantine's courtiers opposed the idea due to a distrust of the Serbians, causing Constantine to question the viability of the match.[51] Ultimately, the opposition of the courtiers to the marriage proved pointless: Mara had no wish to remarry, as she vowed to live a life of celibacy and chastity for the rest of her life once released from the Ottomans. Sphrantzes then decided that a Georgian bride would suit the emperor best and returned to Constantinople in September 1451, bringing a Georgian ambassador with him. Constantine thanked Sphrantzes for his efforts and they agreed that Sphrantzes was to return to Georgia in the spring of 1452 and forge a marriage alliance. Due to mounting tensions with the Ottomans, Sphrantzes ultimately did not return to Georgia.[50]

On 23 March 1450, Helena Dragaš died. She was highly respected among the Byzantines and was mourned deeply. Gemistus Pletho, the Moreot philosopher previously at Constantine's court in the Morea, and Gennadios Scholarios, future Patriarch of Constantinople, both wrote funeral orations praising her. Pletho praised Helena's fortitude and intellect, and compared her to legendary Greek heroine Penelope on account of her prudence. Constantine's other advisors were often at odds with the emperor and each other.[52] Her death left Constantine unsure of which advisor to rely on the most.[53] Andronikos Palaiologos Kantakouzenos, the megas domestikos (or commander-in-chief), disagreed with the emperor on a number of matters, including the decision to marry a Georgian princess instead of an imperial princess from Trebizond. The most powerful figure at the court was Loukas Notaras, an experienced statesman and megas doux (commander-in-chief of the navy). Although Sphrantzes disliked Notaras,[52] he was a close friend of Constantine. As the Byzantine Empire no longer had a navy, Notaras' position was more of an informal prime minister-type role than a position of military command. Notaras believed that Constantinople's massive defenses would stall any attack on the city and allow western Christians to aid them in time. Due to his influence and friendship with the emperor, Constantine was likely influenced by his hopes and ideas.[54] Sphrantzes was promoted to "First Lord of the Imperial Wardrobe": his office gave him near unhindered access to the imperial residence and a position to influence the emperor. Sphrantzes was even more cautious towards the Ottomans than Notaras, and believed the megas doux risked antagonizing the new sultan. Although Sphrantzes also approved of appealing to the west for aid, he believed that any appeals had to be highly discreet in order to avoid Ottoman attention.[55]

Search for allies

Shortly after Murad II's death, Constantine was quick to send envoys to the new Sultan Mehmed II in an attempt to arrange a new truce. Mehmed supposedly received Constantine's envoys with great respect and put their minds to rest through swearing by Allah, the Prophet Muhammad, the Quran, and the angels and archangels that he would live in peace with the Byzantines and their emperor for the rest of his life. Constantine was unconvinced and suspected that Mehmed's mood could abruptly change in the future. In order to prepare for the future possibility of Ottoman attack, Constantine needed to secure alliances and the most powerful realms that might be inclined to aid him were in the West.[56]

The nearest and most concerned potential ally was Venice, which operated a large commercial colony in their quarter of Constantinople. However, the Venetians were not to be trusted. During the first few months of his rule as emperor, Constantine had raised the taxes on the goods the Venetians imported to Constantinople since the imperial treasury was nearly empty and funds had to be raised through some means. In August 1450, the Venetians had threatened to transfer their trade to another port, perhaps one under Ottoman control, and despite Constantine writing to the Doge of Venice, Francesco Foscari, in October 1450, the Venetians were unconvinced and signed a formal treaty with Mehmed II in 1451. To annoy the Venetians, Constantine attempted to seal a deal with the Republic of Ragusa in 1451, offering them a place to trade in Constantinople with limited tax concessions, though the Ragusans could offer little military aid to the empire.[57]

Most of the kingdoms in Western Europe were occupied with their own wars at the time and the crushing defeat at the Battle of Varna had quelled most of the crusading spirit. The news that Murad II had died and been succeeded by his young son also lulled the western Europeans into a false sense of security. To the papacy, the Union of the Churches was a far more pressing concern than the threat of Ottoman attack. In August 1451, Constantine's ambassador Andronikos Bryennios Leontaris arrived in Rome to deliver a letter to Pope Nicholas V, which contained a statement from the anti-unionist synaxis at Constantinople. Constantine hoped that the Pope would read the letter and understand Constantine's difficulties with making the Union of the Churches a reality in the east. The letter contained the synaxis's proposal that a new council be held at Constantinople, with an equal number of representatives from both churches (since the Orthodox had been heavily outnumbered at the previous council). On 27 September, Nicholas V replied to Constantine after he heard that the unionist Patriarch Gregory III had resigned following the opposition against him. Nicholas V merely wrote that Constantine had to try harder to convince his people and clergy and that the price of further military aid from the west was full acceptance of the union achieved at Florence; the name of the Pope had to be commemorated in the churches in Greece and Gregory III had to be reinstated as patriarch. The ultimatum was a setback for Constantine, who had done his best to enforce the union without inciting riots in Constantinople. The Pope appeared to have completely ignored the sentiment of the anti-unionist synaxis. Nicholas V sent a papal legate, Cardinal Isidore of Kiev, to Constantinople to attempt to help Constantine enforce the union, but Isidore did not arrive until October 1452, when the city faced more pressing concerns.[58]

Dealings with Mehmed II

A great-grandson of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, Orhan Çelebi, lived as a hostage in Constantinople. Other than Mehmed II, Orhan was the only known living male member of the Ottoman dynasty, and thus was a potential rival claimant to the sultanate. Mehmed had previously agreed to pay annually for Orhan being kept at Constantinople, but in 1451, Constantine sent a message to the sultan complaining that the payment was not sufficient and hinted that unless more money was paid, Orhan might be released, possibly sparking an Ottoman civil war. The strategy of attempting to use hostage Ottoman princes had been used before by Constantine's father Manuel II, but it was a risky one. Mehmed's grand vizier, Çandarlı Halil Pasha, received the message at Bursa and was appalled at the threat, considering the Byzantine to be inept.[59] Halil had long been relied upon by the Byzantines, through bribes and friendship, to maintain peaceful relations with the Ottomans, but his influence over Mehmed was limited and he was ultimately loyal to the Ottomans, not the Byzantines.[60] Because of the blatant provocation to the sultan, he lost his temper with the Byzantine messengers,[59][61] supposedly shouting:

You stupid Greeks, I have had enough of your devious ways. The late sultan was a lenient and conscientious friend to you. The present sultan is not of the same mind. If Constantine eludes his bold and impetuous grasp, it will only be because God continues to overlook your cunning and wicked schemes. You are fools to think you can frighten us with your fantasies, and that when the ink on our recent treaty is barely dry. We are not children without strength or reason. If you think you can start something, then do so. If you want to proclaim Orhan as Sultan in Thrace, go ahead. If you want to bring the Hungarians across the Danube, let them come. If you want to recover the places which you lost long since, try it. But know this: you will make no headway in any of these things. All that you will achieve is to lose what little you still have.[62]

Constantine and his advisors had catastrophically misjudged the determination of the new sultan.[63] Throughout his brief reign, Constantine and his advisors had been unable to form an effective foreign policy towards the Ottoman Empire. Constantine mainly continued the policy of his predecessors, doing what he could to brace Constantinople for attack, but also alternated between supplicating and confronting the Ottomans. Constantine's advisors had little knowledge and expertise on the Ottoman court and disagreed in how to deal with the Ottoman threat and as Constantine wavered between the opinions of his different councillors, his policy towards Murad and Mehmed was not coherent and resulted in disaster.[64]

Mehmed II considered Constantine to have broken the terms of their 1449 truce and quickly revoked the small concessions he had given to the Byzantines. The threat of releasing Orhan gave Mehmed a pretext for concentrating all of his efforts on seizing Constantinople, his true goal since he had become sultan.[65] Mehmed believed that the conquest of Constantinople was essential to the survival of the Ottoman state: by taking the city, he would prevent any potential crusade from using it as a base and prevent it falling into the hands of a rival more dangerous than the Byzantines.[66] Furthermore, Mehmed had an intense interest in ancient Greco-Roman and medieval Byzantine history, his childhood heroes being figures like Achilles and Alexander the Great.[67]

Mehmed began preparations immediately. In the spring of 1452, work had begun on the Rumelihisarı castle, constructed on the western side of the Bosporus strait, opposite to the already existing Anadoluhisarı castle on the eastern side. With the two castles, Mehmed could control sea traffic in the Bosporus and could blockade Constantinople both by land and sea. Constantine, horrified by the implications of the construction project, protested that Mehmed's grandfather Mehmed I had respectfully asked the permission of Emperor Manuel II before constructing the eastern castle and reminded the sultan of their existing truce.[65] Based on his actions in the Morea, especially during at the time of the Crusade of Varna, Constantine was clearly anti-Turkish and he preferred himself to take aggressive action against the Ottoman Empire; his attempts to appeal to Mehmed were simply a stalling tactic.[68] Mehmed's response to Constantine was that the area he built the fortress on had been uninhabited and that Constantine owned nothing outside of Constantinople's walls.[69]

As panic ensued in Constantinople, the Rumelihisarı was completed in August 1452, intended not only to serve as a means to blockade Constantinople but also as the base from which Mehmed's conquest of Constantinople was to be directed. To clear the site of the new castle, some local churches were demolished, which angered the local Greek populace. Mehmed had them massacred. The Ottomans had sent some animals to graze on Byzantine farmland on the shores of the Sea of Marmara, which also angered the locals. When the Greek farmers protested, Mehmed sent his troops to attack them, killing about forty. Outraged, Constantine formally declared war on Mehmed II, closing the gates of Constantinople and arresting all Turks within the city walls. Seeing the futility in this move, Constantine renounced his actions three days later and set the prisoners free.[65] After the capture of several Italian ships and the execution of their crews during Mehmed's eventual siege of Constantinople, Constantine reluctantly ordered the execution of all Turks within the city walls.[70]

Constantine began to prepare for what was at best a blockade, and at worst a siege, gathering provisions and working to repair Constantinople's walls.[71] Manuel Palaiologos Iagros, one of the envoys who had invested Constantine as emperor in 1449, was put in charge of the restoration of the formidable walls, a project which was completed late in 1452.[72] He sent more urgent requests for aid to the west. Near the end of 1451, he had sent a message to Venice stating that unless they sent reinforcements to him at once, Constantinople would fall to the Ottomans. Although the Venetians were sympathetic to the Byzantine cause, they explained in their reply in February 1452 that although they could ship armor and gunpowder to him, they had no troops to spare as they were fighting against neighboring city-states in Italy at the time. When the Ottomans sank a Venetian trading ship in the Bosporus in November 1452 and executed the ship's survivors on account of the ship refusing to pay a new toll instituted by Mehmed, the Venetian attitude changed as they now also found themselves at war with the Ottomans. Desperate for aid, Constantine sent pleas for reinforcements to his brothers in the Morea and Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples, promising the latter the island of Lemnos if he brought help. The Hungarian warrior John Hunyadi was invited to help and was promised Selymbria or Mesembria if he came with aid. The Genoese on the island Chios were also sent a plea, being promised payment in return for military assistance. Constantine received little practical response to his pleas.[71]

Religious disunity in Constantinople

Above all, Constantine sent many appeals for aid to Pope Nicholas V. Although sympathetic, Nicholas V believed that the papacy could not go to the rescue of the Byzantines unless they fully accepted the Union of the Churches and his spiritual authority. Furthermore, he knew that the papacy alone could not do much against the formidable Ottoman Turks, a similar response to one given by Venice, which promised military assistance only if others in Western Europe also came to Constantinople's defense. On 26 October 1452, Nicholas V's legate, Isidore of Kiev, arrived at Constantinople together with the Latin Archbishop of Mytilene, Leonard of Chios. With them, they brought a small force of 200 Neapolitan archers. Though they made little difference in coming battle, the reinforcements were probably more appreciated by Constantinople's citizens than the actual purpose of Isidore's and Leonard's visit: cementing the Union of the Churches. Their arrival in the city spurred the anti-unionists into a frenzy. On 13 September 1452, a month before Isidore and Leonard arrived, the lawyer and anti-unionist Theodore Agallianos had written a short chronicle of contemporary events,[73] concluding with the following words:

This was written in the third year of the reign of Constantine Palaiologos, who remains uncrowned because the church has no leader and is indeed in disarray as the result of the turmoil and confusion brought upon it by the falsely named union which his brother and predecessor John Palaiologos engineered... This union was evil and displeasing to God and has instead split the church and scattered its children and destroyed us utterly. Truth to tell, this is the source of all our other misfortunes.[74]

Constantine and John VIII before him had badly misjudged the level of opposition against the church union.[1] Loukas Notaras was successful in calming down the situation in Constantinople somewhat, explaining to an assembly of nobles that the Catholic visit was made with good intentions and that the soldiers who had accompanied Isidore and Leonard might just be an advance guard; more military aid might have been on its way. Many nobles were convinced that a spiritual price could be paid for material rewards and that if they were rescued from the immediate danger, there would be time later to think more clearly in a calmer atmosphere. Sphrantzes suggested to Constantine that he name Isidore as the new Patriarch of Constantinople as Gregory III had not been seen for some time and was unlikely to return. Although such an appointment might have gratified the pope and led to further aid being sent, Constantine realized that it would only stir up the anti-unionists more. Once the people of Constantinople realized that no further immediate aid in addition to the 200 soldiers was coming from the papacy, they rioted in the streets.[75]

Leonard of Chios confided in the emperor that he believed him to be far too lenient with the anti-unionists, urging him to arrest their leaders and try harder to push back the opposition to the Union of the Churches. Constantine opposed the idea, perhaps under the assumption that arresting the leaders would turn them into martyrs for their cause. Instead, Constantine summoned the leaders of the synaxis to the imperial palace on 15 November 1452, and once again asked them to write a document with their objections to the union achieved at Florence, which they were eager to do. On 25 November, the Ottomans sank another Venetian trading ship with cannon fire from the new Rumelihisarı castle, an event which captured the minds of the Byzantines and united them in fear and panic. As a result, the anti-unionist cause gradually died down. On 12 December, a Catholic liturgy commemorating the names of the Pope and Patriarch Gregory III was held in the Hagia Sophia by Isidore. Constantine and his court were present, as was a large number of the city's citizens (Isidore stated that all of its inhabitants attended the ceremony).[76]

Final preparations

Constantine's brothers in the Morea could not bring him any help: Turahan had been called on by Mehmed to invade and devastate the Morea again in October 1452 to keep the two despots occupied. The Morea was devastated, with Constantine's brothers only achieving one small success with the capture of Turahan's son, Ahmed, in battle. Constantine then had to rely on the only other parties which had expressed interest in aiding him: Venice, the pope, and Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples. Although Venice had been slow to act, the Venetians in Constantinople acted immediately without waiting for orders when the Ottomans sank their ships. The Venetian bailie in Constantinople, Girolamo Minotto, called an emergency meeting with the Venetians in the city, which was also attended by Constantine and Cardinal Isidore. Most of the Venetians voted to stay in Constantinople and aid the Byzantines in their defense of the city, agreeing that no Venetian ships were to leave Constantinople's harbor. The decision of the local Venetians to stay and die for the city had a significantly greater effect on the Venetian government than Constantine's pleas.[77]

In February 1453, Doge Foscari ordered the preparation of warships and army recruitment, both of which were to head for Constantinople in April. He sent letters to the pope, Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples, King Ladislaus V of Hungary, and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III to inform them that unless Western Christianity acted, Constantinople would fall to the Ottomans. Though the increase in diplomatic activity was impressive, it came too late to save Constantinople: the equipment and financing of a joint papal-Venetian armada took longer than expected,[77] the Venetians had misjudged the amount of time on their hands, and messages took at least a month to travel from Constantinople to Venice.[78] Emperor Frederick III's only response to the crisis was a letter sent to Mehmed II in which he threatened the sultan with an attack from all of western Christendom unless the sultan demolished the Rumelihisarı castle and abandoned his plans to Constantinople. Constantine continued to hope for help and sent more letters in early 1453 to Venice and Alfonso V, asking not only for soldiers but also food as his people were beginning to suffer from the Ottoman blockade of the city. Alfonso responded to his plea by quickly sending a ship with provisions.[77]

Throughout the long winter of 1452–1453, Constantine ordered the citizens of Constantinople to restore the city's imposing walls and gather as many weapons as they could. Ships were sent to the islands still under Byzantine rule to gather further supplies and provisions. The defenders grew anxious as the news of a huge cannon at the Ottoman camp that was assembled by the Hungarian engineer Orban reached the city. Loukas Notaras was given command of the walls along the sea walls of the Golden Horn and various sons of the Palaiologos and Kantakouzenos families were appointed to man other positions. Many of the city's foreign inhabitants, notably the Venetians, offered their aid. Constantine asked them to man the battlements to show the Ottomans how many defenders they were to face. When the Venetians offered their service to guard four of the city's land gates, Constantine accepted and entrusted them with the keys. Some of the city's Genoese population also aided the Byzantines. In January 1453, notable Genoese aid arrived voluntarily in the form of Giovanni Giustiniani—a renowned soldier known for his skill in siege warfare—and 700 soldiers under his command. Giustiniani was appointed by Constantine as the general commander for the walls on Constantinople's land side.[79] Giustiniani was given the rank of protostrator and promised the island of Lemnos as a reward (though it had already been promised to Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples, should he come to the city's aid).[80] In addition to the limited western aid, Orhan Çelebi, the Ottoman contender held as a hostage in the city, and his considerable retinue of Ottoman troops, also assisted in the city's defense.[81]

On 2 April 1453, Mehmed's advance guard arrived outside Constantinople and began pitching up a camp. On 5 April, the sultan himself arrived at the head of his army and encamped within firing range of the city's Gate of St. Romanus. Bombardment of the city walls began almost immediately on 6 April.[82][83] Most estimates of the number of soldiers defending Constantinople's walls in 1453 range from 6,000–8,500, out of which 5,000–6,000 were Greeks, most of whom were untrained militia soldiers.[84] An additional 1,000 Byzantine soldiers were kept as reserves inside the city.[85] Mehmed's army massively outnumbered the Christian defenders; his forces might have been as many as 80,000 men,[86] including about 5,000 elite janissaries.[87] Even then, Constantinople's fall was not inevitable; the strength of the walls made the Ottoman numerical advantage irrelevant at first and under other circumstances, the Byzantines and their allies could have survived until help arrived. The Ottoman use of cannons intensified and sped up the siege considerably.[88]

Fall of Constantinople

Siege

An Ottoman fleet attempted to get into the Golden Horn while Mehmed began bombarding Constantinople's land walls. Foreseeing this possibility, Constantine had constructed a massive chain laid across the Golden Horn which prevented the fleet's passage. The chain was only lifted temporarily a few days after the siege began to allow the passage of three Genoese ships sent by the papacy and a large ship with food sent by Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples.[82] The arrival of these ships on 20 April, and the failure of the Ottomans to stop them, was a significant victory for the Christians and significantly increased their morale. The ships, carrying soldiers, weapons and supplies, had passed by Mehmed's scouts alongside the Bosphorus unnoticed. Mehmed ordered his admiral, Suleiman Baltoghlu, to capture the ships and their crews at all costs. As the naval battle between the smaller Ottoman ships and the large western ships commenced, Mehmed rode his horse into the water to shout unhelpful naval commands to Baltoghlu, who pretended not to hear them. Baltoghlu withdrew the smaller ships so that the few large Ottoman vessels could fire on the western ships, but the Ottoman cannons were too low to do damage to the crews and decks and their shots were too small to seriously damage the hulls. As the sun set, the wind suddenly returned and the ships passed through the Ottoman blockade, aided by three Venetian ships which had sailed out to meet and cover them.[89]

The sea walls were weaker than Constantinople's land walls, and Mehmed was determined to get his fleet into the Golden Horn; he needed some way to circumvent Constantine's chain. On 23 April, the defenders of Constantinople observed the Ottoman fleet managed to get into the Golden Horn by being pulled across a massive series of tracks, constructed on Mehmed's orders, across the hill behind Galata, the Genoese colony on the opposite side of the Golden Horn. Although the Venetians attempted to attack the ships and set fire to them, their attempt was unsuccessful.[82]

As the siege progressed, it became clearer that the forces defending the city would not be enough to man both the sea walls and the land walls. Furthermore, food was running out and as food prices rose to compensate, many of the poor began to starve. On Constantine's orders, the Byzantine garrison collected money from churches, monasteries and private residences to pay for food for the poor. Objects of precious metal held by the churches were seized and melted down, though Constantine promised the clergy that he would repay them four-fold once the battle had been won. The Ottomans bombarded the city's outer walls continuously, and eventually opened up a small breach which exposed the inner defenses. Constantine grew more and more anxious. He sent messages begging the sultan to withdraw, promising whatever amount of tribute he wanted, but Mehmed was determined to take the city.[90] The sultan supposedly responded:

Either I shall take this city, or the city will take me, dead or alive. If you will admit defeat and withdraw in peace, I shall give you the Peloponnese and other provinces for your brothers and we shall be friends. If you persist in denying me peaceful entry into the city, I shall force my way in and I shall slay you and all your nobles; and I shall slaughter all the survivors and allow my troops to plunder at will. The city is all I want, even if it is empty.[90]

To Constantine, the idea of abandoning Constantinople was unthinkable. He did not bother to reply to the sultan's suggestion. Some days after offering Constantine the chance to surrender, Mehmed sent a new messenger to address the citizens of Constantinople, imploring them to surrender and save themselves from death or slavery. The sultan informed them that he would let them live as they were, in exchange for an annual tribute, or allow them to leave the city unharmed with their belongings. Some of Constantine's companions and councilors implored him to escape the city, rather than die in its defense: if he escaped unharmed, Constantine could set up an empire-in-exile in the Morea or somewhere else and carry on the war against the Ottomans. Constantine did not accept their ideas; he refused to be remembered as the emperor who ran away.[90] According to later chroniclers, Constantine's response to the idea of escaping was the following:

God forbid that I should live as an Emperor without an Empire. As my city falls, I will fall with it. Whosoever wishes to escape, let him save himself if he can, and whoever is ready to face death, let him follow me.[91]

Constantine then sent a response to the sultan, the last communication between a Byzantine emperor and an Ottoman sultan:[90]

As to surrendering the city to you, it is not for me to decide or for anyone else of its citizens; for all of us have reached the mutual decision to die of our own free will, without any regard for our lives.[92]

The only hope the citizens could cling to was the news that the Venetian fleet was on its way to relieve Constantinople. When a Venetian reconnaissance ship that had slipped through the Ottoman blockade returned to the city to report that no relief force had been seen, it was made clear that the few forces that had gathered at Constantinople would have to fight the Ottoman army alone. The news that the whole of Christendom appeared to have deserted them unnerved some of the Venetians and Genoese defenders and in-fighting broke out between them, forcing Constantine to remind them that there were more important enemies at hand. Constantine resolved to commit himself and the city to the mercy of Christ;[93] if the city fell, it would be God's will.[90]

Final days and final assault

_by_Jean_Le_Tavernier_after_1455.jpg.webp)

The Byzantines observed strange and ominous signs in the days leading up to the final Ottoman assault on the city. On 22 May, there was a lunar eclipse for three hours, harkening to a prophecy that Constantinople would fall when the moon was on wane. In order to encourage the defenders, Constantine commanded that the icon of Mary, the city's protector, was to be carried in a procession through the streets. The procession was abandoned when the icon slipped from its frame and the weather turned to rain and hail. Carrying out the procession on the next day was impossible as the city became engulfed in a thick fog.[94]

On 26 May, the Ottomans held a war council. Çandarlı Halil Pasha, who believed western military aid to the city was imminent, counseled Mehmed to compromise with the Byzantines and withdraw whereas Zagan Pasha, a military officer, urged the sultan to push on and pointed out that Alexander the Great had conquered almost the entire known world when he was young. Perhaps knowing that they would support a final assault, Mehmed ordered Zagan to tour the camp and gather the opinions of the soldiers.[95] On the evening of 26 May, the dome of the Hagia Sophia was lit up by a strange and mysterious light phenomenon, also spotted by the Ottomans from their camp outside the city. The Ottomans saw it as a great omen for their victory and the Byzantines saw it as a sign of impending doom. 28 May was calm, as Mehmed had ordered a day of rest before his final assault. The citizens who had not been put to work on repairing the crumbling walls or manning them prayed in the streets. On Constantine's orders, icons and relics from all the monasteries and churches in the city were carried along the walls. Both Catholics and Orthodox defenders joined together in prayers and hymns and Constantine led the procession himself.[94] Giustiniani sent word to Loukas Notaras to request that Notaras' artillery be brought to defend the land walls, which Notaras refused. Giustiniani accused Notaras of treachery and they almost fought each other before Constantine intervened.[95]

In the evening, the crowds moved to the Hagia Sophia, with Orthodox and Catholic Christians joining together and praying, the fear of impending doom having done more to unite them than the councils ever could. Cardinal Isidore was in attendance, as was Emperor Constantine. Constantine prayed and asked for forgiveness and remission of his sins from all the bishops there before he received communion at the church's altar. The emperor then left the church, going to the imperial palace and asking his household there for forgiveness and saying farewell to them before again disappearing into the night, going to make a final inspection of the soldiers manning the city walls.[96]

Without warning, the Ottomans began their final assault in the early hours of 29 May.[97] The service in the Hagia Sophia was interrupted, with fighting-age men rushing to the walls to defend the city and the other men and women helping the parts of the army stationed within the city.[98] Waves of Mehmed's troops charged at Constantinople's land walls, hammering at the weakest section for more than two hours. Despite the relentless attack, the defense, led by Giustiniani and supported by Constantine, held firm.[97] Unbeknownst to anyone, after six hours of fighting, just before sunrise,[97] Giustiniani was mortally wounded.[99] Constantine begged Giustiniani to stay and continue fighting,[97] allegedly saying:

My brother, fight bravely. Do not forsake us in your distress. The salvation of the City depends on you. Return to your post. Where are you going?[99]

Giustiniani was too weak, however, and his bodyguards carried him to the harbor and escaped the city on a Genoese ship. The Genoese troops wavered when they saw their commander leave them, and though the Byzantine defenders fought on, the Ottomans soon gained control of both the outer and inner walls. About fifty Ottoman soldiers made it through one of the gates, the Kerkoporta, and were the first of the enemy to enter Constantinople; it had been left unlocked and ajar by a Venetian party the night before. Ascending up the tower above the Kerkoporta, they managed to raise an Ottoman flag above the wall. The Ottomans stormed through the wall and many of the defenders panicked with no means of escape. Constantinople had fallen.[97] Giustiniani died of his wounds on his way home. Loukas Notaras was initially captured alive before being executed shortly after. Cardinal Isidore disguised himself as a slave and escaped across the Golden Horn to Galata. Orhan, Mehmed's cousin, disguised himself as a monk in an attempt to escape, but was identified and killed.[100]

Death

Constantine died the day Constantinople fell. There were no known surviving eyewitnesses to the death of the emperor and none of his entourage survived to offer any credible account of his death.[101][102] The Greek historian Michael Critobulus, who later worked in the service of Mehmed, wrote that Constantine died fighting the Ottomans. Later Greek historians accepted Critobulus's account, never doubting that Constantine died as a hero and martyr, an idea never seriously questioned in the Greek-speaking world.[103] Though none of the authors were eyewitnesses, a vast majority of those who wrote of Constantinople's fall, both Christians and Muslims, agree that Constantine died in the battle, with only three accounts claiming that the emperor escaped the city. It also seems probable that his body was later found and decapitated.[104] According to Critobulus, the last words of Constantine before he charged at the Ottomans were "the city is fallen and I am still alive".[105] There were other conflicting contemporary accounts of Constantine's demise. Leonard of Chios, who was taken prisoner by the Ottomans but later managed to escape, wrote that once Giustiniani had fled the battle, Constantine's courage failed and the emperor implored his young officers to kill him so that he would not be captured alive by the Ottomans. None of the soldiers were brave enough to kill the emperor and once the Ottomans broke through, Constantine fell in the ensuing fight, only to briefly get up before falling again and being trampled. The Venetian physician Niccolò Barbaro, who was present at the siege, wrote that no one knew if the emperor had died or escaped the city alive, noting that some said that his corpse had been seen among the dead while others claimed that he had hanged himself as soon as the Ottomans had broken through at the St. Romanus gate. Cardinal Isidore wrote, like Critobulus, that Constantine had died fighting at the St. Romanus gate. Isidore also added that he had heard that the Ottomans had found his body, cut off his head and presented it to Mehmed as a gift, who was delighted and showered the head with insults before taking it with him to Adrianople as a trophy. Jacopo Tedaldi, a merchant from Florence who participated in the final fight, wrote that "some say that his head was cut off; others that he perished in the crush at the gate. Both stories may well be true".[106]

Ottoman accounts of Constantine's demise all agree that the emperor was decapitated. Tursun Beg, who was part of Mehmed's army at the battle, wrote a less heroic account of Constantine's death than the Christian authors. According to Tursun, Constantine panicked and fled, making for the harbor in hopes of finding a ship to escape the city. On his way there, he came across a band of Turkish marines, and after charging and nearly killing one of them, was decapitated. A later account by Ottoman historian Ibn Kemal is similar to Tursun's account, but states that the emperor's head was cut off by a giant marine, who killed him without realizing who he was.[107] Nicola Sagundino, a Venetian who had once been a prisoner of the Ottomans following their conquest of Thessaloniki decades before, gave an account of Constantine's death to Alfonso V of Aragon and Naples in 1454 since he believed that the emperor's fate "deserved to be recorded and remembered for all time". Sagundino stated that although Giustiniani implored the emperor to escape as he was carried away after falling on the battlefield, Constantine refused and preferred to die with his empire. Constantine went to where the fighting appeared to be thickest and, as it would be unworthy of him to be captured alive, implored his officers to kill him. When none of them obeyed his command, Constantine threw off his imperial regalia, as to not let himself be distinguished from the other soldiers, and disappeared into the fray, sword in hand. When Mehmed wanted the defeated Constantine to be brought to him, he was told it was too late as the emperor was dead. A search for the body was conducted, and when it was found, the emperor's head was cut off and paraded through Constantinople before it was sent to the Sultan of Egypt as a gift, alongside twenty captured women and forty captured men.[108]

Legacy

Historiography

Constantine's death marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, an institution tracing its origin to Constantine the Great's foundation of Constantinople as the Roman Empire's new capital in 330. Even as their realm gradually became more restricted to only Greek-speaking lands, the people of the Byzantine Empire continually maintained that they were Romaioi (Romans), not Hellenes (Greeks); as such, Constantine's death also marked the definitive end of the Roman Empire that was founded by Augustus 1,480 years earlier.[109] Constantine's death and the Fall of Constantinople also marked the true birth of the Ottoman Empire, which dominated much of the eastern Mediterranean until its fall in 1922. The conquest of Constantinople had been a dream of Islamic armies since the 8th century and through its possession, Mehmed II and his successors claimed to be the heirs of the Roman emperors.[110]

There is no evidence that Constantine ever rejected the hated union of the Churches achieved at Florence in 1439 after spending a lot of energy to realize it. Many of his subjects had chastised him as a traitor and heretic while he lived and he, like many of his predecessors before him, died in communion with the Church of Rome. Nevertheless, Constantine's actions during the Fall of Constantinople and his death fighting the Turks redeemed the popular view of him. The Greeks forgot or ignored that Constantine had died a "heretic", and many considered him a martyr. In the eyes of the Orthodox Church, Constantine's death sanctified him and he died a hero.[111] In Athens, the modern capital of Greece, there are two statues of Constantine: a colossal monument depicting the emperor on horseback on the waterfront of Palaio Faliro, and a smaller statue in the city's cathedral square, which portrays the emperor on foot with a drawn sword. There are no statues of emperors such as Basil II or Alexios I Komnenos, who were significantly more successful and died of natural causes after long and glorious reigns.[102]

Scholarly works on Constantine and the fall of Constantinople tend to portray Constantine, his advisors, and companions as victims of the events that surrounded the city's fall. There are three main works that deal with Constantine and his life: the earliest is Čedomilj Mijatović's Constantine Palaeologus (1448–1453) or The Conquest of Constantinople by the Turks (1892), written at a time when tensions were rising between the relatively new Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire. War appeared imminent and Mijatović's work was intended to serve as propaganda for the Greek cause by portraying Constantine as a tragic victim of events he had no possibility of affecting. The text is dedicated to the young Prince Constantine, of the same name as the old emperor and the heir to the Greek throne, and its preface states that "Constantinople may soon again change masters", alluding to the possibility that Greece might conquer the ancient city.[112]

The second major work on Constantine, Steven Runciman's The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (1965), also characterizes Constantine through Constantinople's fall, portraying Constantine as tragic figure who did everything to save his empire from the Ottomans. However, Runciman partly blames Constantine for antagonizing Mehmed II through his threats concerning Orhan. The third major work, Donald Nicol's The Immortal Emperor: The Life and Legend of Constantine Palaiologos, Last Emperor of the Romans (1992), examines Constantine's entire life and analyzes the trials and hardships he faced not only as emperor, but as Despot of the Morea as well. Nicol's work places considerably less emphasis on the importance of individuals than the preceding works do, though Constantine is again portrayed as a mostly tragic figure.[113]