Controversies surrounding the eurozone crisis

The eurozone crisis is an ongoing financial crisis that has made it difficult or impossible for some countries in the euro area to repay or re-finance their government debt without the assistance of third parties.

The European sovereign debt crisis resulted from a combination of complex factors, including the globalization of finance; easy credit conditions during the 2002–2008 period that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices; the financial crisis of 2007–08; international trade imbalances; real-estate bubbles that have since burst; fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses; and approaches used by nations to bail out troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socializing losses. [1][2]

One narrative describing the causes of the crisis begins with the significant increase in savings available for investment during the 2000–2007 period when the global pool of fixed-income securities increased from approximately $36 trillion in 2000 to $70 trillion by 2007. This "Giant Pool of Money" increased as savings from high-growth developing nations entered global capital markets. Investors searching for higher yields than those offered by U.S. Treasury bonds sought alternatives globally.[3]

The temptation offered by such readily available savings overwhelmed the policy and regulatory control mechanisms in country after country, as lenders and borrowers put these savings to use, generating bubble after bubble across the globe. While these bubbles have burst, causing asset prices (e.g., housing and commercial property) to decline, the liabilities owed to global investors remain at full price, generating questions regarding the solvency of governments and their banking systems.[1]

How each European country involved in this crisis borrowed and invested the money varies. For example, Ireland's banks lent the money to property developers, generating a massive property bubble. When the bubble burst, Ireland's government and taxpayers assumed private debts. In Greece, the government increased its commitments to public workers in the form of extremely generous wage and pension benefits, with the former doubling in real terms over 10 years.[4] Iceland's banking system grew enormously, creating debts to global investors (external debts) several times GDP.[1][5]

The interconnection in the global financial system means that if one nation defaults on its sovereign debt or enters into recession putting some of the external private debt at risk, the banking systems of creditor nations face losses. For example, in October 2011, Italian borrowers owed French banks $366 billion (net). Should Italy be unable to finance itself, the French banking system and economy could come under significant pressure, which in turn would affect France's creditors and so on. This is referred to as financial contagion.[6][7] Another factor contributing to interconnection is the concept of debt protection. Institutions entered into contracts called credit default swaps (CDS) that result in payment should default occur on a particular debt instrument (including government issued bonds). But, since multiple CDSs can be purchased on the same security, it is unclear what exposure each country's banking system now has to CDS.[8]

Greece hid its growing debt and deceived EU officials with the help of derivatives designed by major banks.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Although some financial institutions clearly profited from the growing Greek government debt in the short run,[9] there was a long lead-up to the crisis.

The European bailouts are largely about shifting exposure from banks and others, who otherwise are lined up for losses on the sovereign debt they have piled up, onto European taxpayers.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

EU treaty violations

No bail-out clause

The EU's Maastricht Treaty contains juridical language which appears to rule out intra-EU bailouts. First, the "no bail-out" clause (Article 125 TFEU) ensures that the responsibility for repaying public debt remains national and prevents risk premiums caused by unsound fiscal policies from spilling over to partner countries. The clause thus encourages prudent fiscal policies at the national level.

The European Central Bank's purchase of distressed country bonds has caused many controversies and has been seen by many as violating the prohibition of monetary financing of budget deficits (Article 123 TFEU). It must be emphasized that these bonds are purchased as part of the Outright Monetary Transactions program, which operates exclusively on the secondary market (i.e. the bonds are bought from other investors and not directly from the countries at issuance) and does not therefore constitute an overdraft or credit facility. The creation of further leverage in EFSF with access to ECB lending would also appear to violate the terms of this article.

Articles 125 and 123 were meant to create disincentives for EU member states to run excessive deficits and state debt, and prevent the moral hazard of over-spending and lending in good times. They were also meant to protect the taxpayers of the other more prudent member states. By issuing bail-out aid guaranteed by prudent eurozone taxpayers to rule-breaking eurozone countries such as Greece, the EU and eurozone countries also encourage moral hazard in the future.[21] While the no bail-out clause remains in place, the "no bail-out doctrine" seems to be a thing of the past.[22]

Convergence criteria

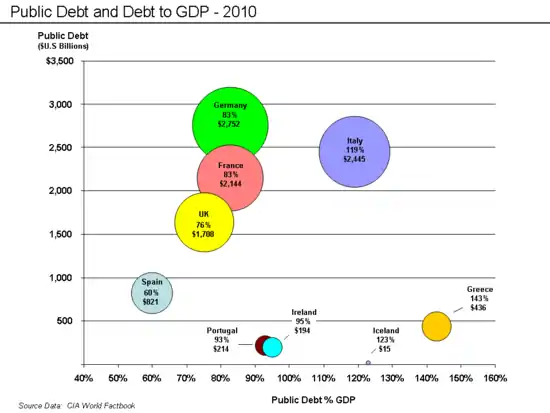

The EU treaties contain so called convergence criteria, specified in the protocols of the Treaties of the European Union. Concerning government finance the states have agreed that the annual government budget deficit should not exceed 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and that the gross government debt to GDP should not exceed 60% of the GDP (see protocol 12 and 13). For eurozone members there is the Stability and Growth Pact which contains the same requirements for budget deficit and debt limitation but with a much stricter regime. In the past, many European countries including Greece and Italy have substantially exceeded these criteria over a long period of time.[23]

Actors fueling the crisis

Credit rating agencies

The international U.S.-based credit rating agencies—Moody's, Standard & Poor's and Fitch—which have already been under fire during the housing bubble[24][25] and the Icelandic crisis[26][27]—have also played a central and controversial role[28] in the current European bond market crisis.[29] On one hand, the agencies have been accused of giving overly generous ratings due to conflicts of interest.[30] On the other hand, ratings agencies have a tendency to act conservatively, and to take some time to adjust when a firm or country is in trouble.[31] In the case of Greece, the market responded to the crisis before the downgrades, with Greek bonds trading at junk levels several weeks before the ratings agencies began to describe them as such.[32]

According to a study by economists at St Gallen University credit rating agencies have fueled rising euro zone indebtedness by issuing more severe downgrades since the sovereign debt crisis unfolded in 2009. The authors concluded that rating agencies were not consistent in their judgments, on average rating Portugal, Ireland and Greece 2.3 notches lower than under pre-crisis standards, eventually forcing them to seek international aid.[33]

European policy makers have criticized ratings agencies for acting politically, accusing the Big Three of bias towards European assets and fueling speculation.[34] Particularly Moody's decision to downgrade Portugal's foreign debt to the category Ba2 "junk" has infuriated officials from the EU and Portugal alike.[34] State owned utility and infrastructure companies like ANA – Aeroportos de Portugal, Energias de Portugal, Redes Energéticas Nacionais, and Brisa – Auto-estradas de Portugal were also downgraded despite claims to having solid financial profiles and significant foreign revenue.[35][36][37][38]

France too has shown its anger at its downgrade. French central bank chief Christian Noyer criticized the decision of Standard & Poor's to lower the rating of France but not that of the United Kingdom, which "has more deficits, as much debt, more inflation, less growth than us". Similar comments were made by high-ranking politicians in Germany. Michael Fuchs, deputy leader of the leading Christian Democrats, said: "Standard and Poor's must stop playing politics. Why doesn't it act on the highly indebted United States or highly indebted Britain?", adding that the latter's collective private and public sector debts are the largest in Europe. He further added: "If the agency downgrades France, it should also downgrade Britain in order to be consistent."[39]

Credit rating agencies were also accused of bullying politicians by systematically downgrading eurozone countries just before important European Council meetings. As one EU source put it: "It is interesting to look at the downgradings and the timings of the downgradings ... It is strange that we have so many downgrades in the weeks of summits."[40]

Regulatory reliance on credit ratings

Think-tanks such as the World Pensions Council (WPC) have criticized European powers such as France and Germany for pushing for the adoption of the Basel II recommendations, adopted in 2005 and transposed in European Union law through the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD), effective since 2008. In essence, this forced European banks and more importantly the European Central Bank, e.g. when gauging the solvency of EU-based financial institutions, to rely heavily on the standardized assessments of credit risk marketed by only two private US firms- Moody's and S&P.[41]

Counter measures

Due to the failures of the ratings agencies, European regulators obtained new powers to supervise ratings agencies.[28] With the creation of the European Supervisory Authority in January 2011 the EU set up a whole range of new financial regulatory institutions,[42] including the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA),[43] which became the EU's single credit-ratings firm regulator.[44] Credit-ratings companies have to comply with the new standards or will be denied operation on EU territory, says ESMA Chief Steven Maijoor.[45]

Germany's foreign minister Guido Westerwelle has called for an "independent" European ratings agency, which could avoid the conflicts of interest that he claimed US-based agencies faced.[46] European leaders are reportedly studying the possibility of setting up a European ratings agency in order that the private U.S.-based ratings agencies have less influence on developments in European financial markets in the future.[47][48] According to German consultant company Roland Berger, setting up a new ratings agency would cost €300 million. On 30 January 2012, the company said it was already collecting funds from financial institutions and business intelligence agencies to set up an independent non-profit ratings agency by mid-2012, which could provide its first country ratings by the end of the year.[49] In April 2012, in a similar attempt, the Bertelsmann Stiftung presented a blueprint for establishing an international non-profit credit rating agency (INCRA) for sovereign debt, structured in way that management and rating decisions are independent from its financiers.[50]

But attempts to regulate more strictly credit rating agencies in the wake of the European sovereign debt crisis have been rather unsuccessful. World Pensions Council (WPC) financial law and regulation experts have argued that the hastily drafted, unevenly transposed in national law, and poorly enforced EU rule on ratings agencies (Regulation EC N° 1060/2009) has had little effect on the way financial analysts and economists interpret data or on the potential for conflicts of interests created by the complex contractual arrangements between credit rating agencies and their clients"[51]

Media

Some in the Greek, Spanish, and French press and elsewhere spread conspiracy theories that claimed that the U.S. and Britain were deliberately promoting rumors about the euro in order to cause its collapse or to distract attention from their own economic vulnerabilities. The Economist rebutted these "Anglo-Saxon conspiracy" claims, writing that although American and British traders overestimated the weakness of southern European public finances and the probability of the breakup of the eurozone breakup, these sentiments were an ordinary market panic, rather than some deliberate plot.[52]

Greek Prime Minister Papandreou is quoted as saying that there was no question of Greece leaving the euro and suggested that the crisis was politically as well as financially motivated. "This is an attack on the eurozone by certain other interests, political or financial".[53] The Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero has also suggested that the recent financial market crisis in Europe is an attempt to undermine the euro.[54][55] He ordered the Centro Nacional de Inteligencia intelligence service (National Intelligence Center, CNI in Spanish) to investigate the role of the "Anglo-Saxon media" in fomenting the crisis.[56][57][58][59][60] So far no results have been reported from this investigation.

A major reason for this media coverage were Greek officials' unprecedented statements acknowledging Greece's serious economic woes. For example, during an EU summit at December 2009, newly elected Greek Prime Minister Georges Papandreou said that the public sector is corrupt, a statement later repeated to the international media by José Manuel Barroso,[61] European Commission -president. The previous month, Papandreou said "we need to save the country from the bankruptcy," a statement to which the market reacted.[62]

Speculators

Both the Spanish and Greek Prime Ministers have accused financial speculators and hedge funds of worsening the crisis by short selling euros.[63][64] German chancellor Merkel has stated that "institutions bailed out with public funds are exploiting the budget crisis in Greece and elsewhere."[65]

The role of Goldman Sachs[66] in Greek bond yield increases is also under scrutiny.[67] It is not yet clear to what extent this bank has been involved in the unfolding of the crisis or if they have made a profit as a result of the sell-off on the Greek government debt market.

In response to accusations that speculators were worsening the problem, some markets banned naked short selling for a few months.[68]

Speculation about the breakup of the eurozone

Economists, mostly from outside Europe and associated with Modern Monetary Theory and other post-Keynesian schools, condemned the design of the euro currency system from the beginning because it ceded national monetary and economic sovereignty but lacked a central fiscal authority. When faced with economic problems, they maintained, "Without such an institution, EMU would prevent effective action by individual countries and put nothing in its place."[69][70] US economist Martin Feldstein went so far to call the euro "an experiment that failed".[71] Some non-Keynesian economists, such as Luca A. Ricci of the IMF, contend the eurozone does not fulfill the necessary criteria for an optimum currency area, though it is moving in that direction.[72][73]

As the debt crisis expanded beyond Greece, these economists continued to advocate, albeit more forcefully, the disbandment of the eurozone. If this was not immediately feasible, they recommended that Greece and the other debtor nations unilaterally leave the eurozone, default on their debts, regain their fiscal sovereignty, and re-adopt national currencies.[74][75][76][77][78] Bloomberg suggested in June 2011 that, if the Greek and Irish bailouts should fail, an alternative would be for Germany to leave the eurozone in order to save the currency through depreciation[79] instead of austerity. The likely substantial fall in the euro against a newly reconstituted Deutsche Mark would give a "huge boost" to its members' competitiveness.[80]

Iceland, not part of the EU, is regarded as one of Europe's recovery success stories. It defaulted on its debt and drastically devalued its currency, which has effectively reduced wages by 50% making exports more competitive.[81] Lee Harris argues that floating exchange rates allows wage reductions by currency devaluations, a politically easier option than the economically equivalent but politically impossible method of lowering wages by political enactment.[82] Sweden's floating rate currency gives it a short term advantage, structural reforms and constraints account for longer-term prosperity. Labor concessions, a minimal reliance on public debt, and tax reform helped to further a pro-growth policy.[83]

The Wall Street Journal conjectured as well that Germany could return to the Deutsche Mark,[84] or create another currency union[85] with the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Luxembourg and other European countries such as Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the Baltics.[86] A monetary union of these countries with current account surpluses would create the world's largest creditor bloc, bigger than China[87] or Japan. The Wall Street Journal added that without the German-led bloc, a residual euro would have the flexibility to keep interest rates low[88] and engage in quantitative easing or fiscal stimulus in support of a job-targeting economic policy[89] instead of inflation targeting in the current configuration.

Breakup vs. deeper integration

However, there is opposition in this view. The national exits are expected to be an expensive proposition. The breakdown of the currency would lead to insolvency of several euro zone countries, a breakdown in intrazone payments. Having instability and the public debt issue still not solved, the contagion effects and instability would spread into the system.[90] Having that the exit of Greece would trigger the breakdown of the eurozone, this is not welcomed by many politicians, economists and journalists. According to Steven Erlanger from The New York Times, a "Greek departure is likely to be seen as the beginning of the end for the whole euro zone project, a major accomplishment, whatever its faults, in the postwar construction of a Europe "whole and at peace."[91] Likewise, the two big leaders of the Euro zone, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former French President Nicolas Sarkozy have said on numerous occasions that they would not allow the eurozone to disintegrate and have linked the survival of the Euro with that of the entire European Union.[92][93] In September 2011, EU commissioner Joaquín Almunia shared this view, saying that expelling weaker countries from the euro was not an option: "Those who think that this hypothesis is possible just do not understand our process of integration".[94] The former ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet also denounced the possibility of a return of the Deutsche Mark.[95]

The challenges to the speculation about the breakup or salvage of the eurozone is rooted in its innate nature that the breakup or salvage of eurozone is not only an economic decision but also a critical political decision followed by complicated ramifications that "If Berlin pays the bills and tells the rest of Europe how to behave, it risks fostering destructive nationalist resentment against Germany and ....it would strengthen the camp in Britain arguing for an exit—a problem not just for Britons but for all economically liberal Europeans.[96] Solutions which involve greater integration of European banking and fiscal management and supervision of national decisions by European umbrella institutions can be criticized as Germanic domination of European political and economic life.[97] According to US author Ross Douthat "This would effectively turn the European Union into a kind of postmodern version of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, with a Germanic elite presiding uneasily over a polyglot imperium and its restive local populations".[97]

The Economist provides a somewhat modified approach to saving the euro in that "a limited version of federalization could be less miserable solution than break-up of the euro."[96] The recipe to this tricky combination of the limited federalization, greatly lies on mutualization for limiting the fiscal integration. In order for overindebted countries to stabilize the dwindling euro and economy, the overindebted countries require "access to money and for banks to have a "safe" euro-wide class of assets that is not tied to the fortunes of one country" which could be obtained by "narrower Eurobond that mutualises a limited amount of debt for a limited amount of time."[96] The proposition made by German Council of Economic Experts provides detailed blue print to mutualize the current debts of all euro-zone economies above 60% of their GDP. Instead of the breakup and issuing new national governments bonds by individual euro-zone governments, "everybody, from Germany (debt: 81% of GDP) to Italy (120%) would issue only these joint bonds until their national debts fell to the 60% threshold. The new mutualized-bond market, worth some €2.3 trillion, would be paid off over the next 25 years. Each country would pledge a specified tax (such as a VAT surcharge) to provide the cash." However, so far German Chancellor Angela Merkel has opposed to all forms of mutualization.[96]

The Hungarian-American business magnate George Soros warns in "Does the Euro have a Future?" that there is no escape from the "gloomy scenario" of a prolonged European recession and the consequent threat to the Eurozone's political cohesion so long as "the authorities persist in their current course." He argues that to save the Euro long-term structural changes are essential in addition to the immediate steps needed to arrest the crisis. The changes he recommends include even greater economic integration of the European Union.[98] Soros writes that a treaty is needed to transform the European Financial Stability Fund into a full-fledged European Treasury. Following the formation of the Treasury, European Council could then ask the European Commission Bank to step into the breach and indemnify the European Commission Bank in advance against potential risks to the Treasury's solvency. Soros acknowledges that converting the EFSF into a European Treasury will necessitate "a radical change of heart." In particular, he cautions, Germans will be wary of any such move, not least because many continue to believe that they have a choice between saving the Euro and abandoning it. Soros writes however that a collapse of European Union would precipitate an uncontrollable financial meltdown and thus "the only way" to avert "another Great Depression" is the formation of a European Treasury.[98]

The British betting company Ladbrokes stopped taking bets on Greece exiting the Eurozone in May 2012 after odds fell to 1/3, and reported "plenty of support" for 33/1 odds for a complete disbanding of the Eurozone during 2012.[99]

Odious debt

Some protesters, commentators such as Libération correspondent Jean Quatremer and the Liège-based NGO Committee for the Abolition of the Third World Debt (CADTM) allege that the debt should be characterized as odious debt.[100] The Greek documentary Debtocracy,[101] and a book of the same title and content examine whether the recent Siemens scandal and uncommercial ECB loans which were conditional on the purchase of military aircraft and submarines are evidence that the loans amount to odious debt and that an audit would result in invalidation of a large amount of the debt.[102]

Manipulated debt and deficit statistics

In 1992, members of the European Union signed an agreement known as the Maastricht Treaty, under which they pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels. However, a number of EU member states, including Greece and Italy, were able to circumvent these rules and mask their deficit and debt levels through the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures.[103][104] The structures were designed by prominent U.S. investment banks, who received substantial fees in return for their services and who took on little credit risk themselves thanks to special legal protections for derivatives counterparties.[103] Financial reforms within the U.S. since the financial crisis have only served to reinforce special protections for derivatives—including greater access to government guarantees—while minimizing disclosure to broader financial markets.[105]

The revision of Greece's 2009 budget deficit from a forecast of "6–8% of GDP" to 12.7% by the new Pasok Government in late 2009 (a number which, after reclassification of expenses under IMF/EU supervision was further raised to 15.4% in 2010) has been cited as one of the issues that ignited the Greek debt crisis.

This added a new dimension in the world financial turmoil, as the issues of "creative accounting" and manipulation of statistics by several nations came into focus, potentially undermining investor confidence.

The focus has naturally remained on Greece due to its debt crisis. There has however been a growing number of reports about manipulated statistics by EU and other nations aiming, as was the case for Greece, to mask the sizes of public debts and deficits. These have included analyses of examples in several countries[106][107][108][109][110] or have focused on Italy,[111] the United Kingdom,[112][113][114][115][116][117][118] Spain,[119][120] the United States,[121][122][123] [124] and even Germany.[125][126][127]

Collateral for Finland

On 18 August 2011, as requested by the Finnish parliament as a condition for any further bailouts, it became apparent that Finland would receive collateral from Greece, enabling it to participate in the potential new €109 billion support package for the Greek economy.[128] Austria, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Slovakia responded with irritation over this special guarantee for Finland and demanded equal treatment across the eurozone, or a similar deal with Greece, so as not to increase the risk level over their participation in the bailout.[129] The main point of contention was that the collateral is aimed to be a cash deposit, a collateral the Greeks can only give by recycling part of the funds loaned by Finland for the bailout, which means Finland and the other eurozone countries guarantee the Finnish loans in the event of a Greek default.[130]

After extensive negotiations to implement a collateral structure open to all eurozone countries, on 4 October 2011, a modified escrow collateral agreement was reached. The expectation is that only Finland will use it, due to i.a. requirement to contribute initial capital to European Stability Mechanism in one installment instead of five installments over time. Finland, as one of the strongest AAA countries, can raise the required capital with relative ease.[131]

At the beginning of October, Slovakia and Netherlands were the last countries to vote on the EFSF expansion, which was the immediate issue behind the collateral discussion, with a mid-October vote.[132] On 13 October 2011 Slovakia approved euro bailout expansion, but the government has been forced to call new elections in exchange.

In February 2012, the four largest Greek banks agreed to provide the €880 million in collateral to Finland in order to secure the second bailout program.[133]

Finland's recommendation to the crisis countries is to issue asset-backed securities to cover the immediate need, a tactic successfully used in Finland's early 1990s recession,[134] in addition to spending cuts and bad banking.

Effects of IMF/EU austerity policies

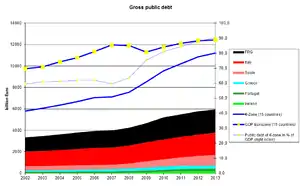

The recessions experienced in bailed-out countries have been connected with elements of the imposed austerity policies. Especially in Greece, the steep rise of debt-to-GDP ratio (which has climbed to 169,1% in 2013) is predominantly a result of the GDP contraction (in absolute numbers, debt has only risen from 300 billion Euros in 2009 to 320 billion Euros in 2013[135]). A discussion on the relevant policy "errors" is still ongoing.[136][137]

After the sovereign debt crisis, five eurozone governments received conditional financial assistance from the Troika, namely the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank and the European Commission. In return for the loans and debt restructuring, the implementation of certain measures was mandatory to get the country's finances back on track. The aim was to restore stability and ensure sustainable economic growth. All conditionality programs included measures to reduce public spending, but also to promote an internal devaluation mechanism with a reduction in wages. In addition, liberalization of protected professions, privatization of public enterprises, and reduction of excessive private rents were present in all the MoUs.[138]

In March 2010, the announcement of the rescue mechanisms for Greece was made at the European Council. The program consists of coordinated bilateral loans provided by the IMF for 1/3 of the program and by the European Union for 2/3 of the program.[139]

These conditionality programs have been the subject of much criticism. For example, scholars have pointed to a shift in power within the European Union to Germany and the European institutions. Indeed, instead of helping domestic banks and the country's economy, the funds allocated to Greece's first rescue plan were used almost exclusively to reimburse foreign banks, mainly French and German, which had invested heavily in Greek banks. This postponement partly explains the fact that a large part of the funds for restructuring the Greek economy allocated by the Troika's reform programs were used to pay off short-term creditors, i.e., foreign banks. However, the criticism by many economists, including Joseph Stiglitz, that the refinancing funds allocated benefited only foreign banks is unfounded, since one-third of the sovereign debt was held by Greek banks and other domestic financial institutions.

The researchers also pointed out that indebted governments were forced to implement very specific reforms against their will. For example, Joseph Stiglitz pointed out that in Greece, reforms were imposed on the price of bread or on pharmaceutical products.[140] According to the Nobel laureate, the reforms imposed on Greece did not reflect the real problem of its economy.

In the case of Greece, a paradox seems to have emerged. Indeed, a default of the country was expected if it did not pursue the economic adjustment program, while at the same time, the MoU seems not to be sustainable for the Greek population and especially to reverse the downward trend of its economy. Indeed, Yanis Varoufakis recalled a discussion with Christine Lagarde when she was head of the IMF. According to the former finance minister, she said that the adjustment programs were not sustainable, but that it was politically mandatory to implement them since the eurozone was in the middle of an impressive economic storm.[141] Although these measures were necessary to support the country and avoid bankruptcy, the measures taken by the Troika were deemed to be too ill-considered. Indeed, the adjustment programs based on indiscriminate tax hikes and horizontal cuts in public spending, including wages and pensions, have caused the deepest recession since the post-war period.[142]

According to Olivier Blanchard, the 2010 reform program only served to increase the debt and required too much fiscal adjustment, resulting in an unprecedented economic depression. However, he argues that if Greece had been left to its own devices, the social cost would have been much higher than under the reform programs. Moreover, while austerity is an extreme burden on an economy, it was seen as essential to put the country's finances in order.[143]

When we talk about austerity, however, we can say that it is not a bad solution per se and that it can be adapted in certain cases. For example, if a significant increase in sovereign debt is due to fiscal laxity, austerity is a must. It is one of the only ways to eliminate the practices that create this massive increase. However, some public expenditures are less appropriate for such an intervention measure, namely wages and pensions. In addition, there are some dangers to consider, such as the fact that widespread private deleveraging may depress demand. Indeed, it is necessary for the proper functioning of an austerity policy that the private sector be able to compensate for government budget cuts by increasing private consumption or activity.[144] The austerity policies introduced by the Troika during the sovereign debt crisis were not sufficiently analyzed before being implemented. Indeed, it is commonly accepted that an austerity policy aimed only at reducing deficits without taking into account the nature of expenditures and revenues can trigger a vicious circle and depress demand. The Keynesian multiplier can work in the opposite direction and worsen the fiscal situation.[145] Moreover, austerity is not able to work if the growth rate is lower than the real interest rate. The problems nowadays are the extremely low nominal interest rates that have led to a liquidity trap which complicated the proper implementation of austerity policies.

In the case of Greece, the austerity policies were put in place on the one hand to reduce the Greek deficit in order to reduce the debt – unnecessary spending in the country will be reduced and thus Greece will return to sustainable growth – and on the other hand to reassure the markets about the country's financial sustainability. The austerity policies carried out between 2010 and 2015 brought Greek budgets back into balance but contributed strongly to the acceleration of the country's debt, unable to repay the loans that had matured with depressed demand in the country. The first three years of internal devaluation under the austerity programs thus led to a significant recession in the country.

These programs eliminated Greece's large fiscal and external account deficits before the crisis. However, these adjustments were made at the expense of the population with a very large number of layoffs. Paul Krugman has suggested that the creditors' approach to austerity programs could be considered wrong since these approaches focused on budget cuts that affect economic growth.

However, while much of the research has emphasized the impossibility for indebted countries to go against austerity programs, some research has shown the opposite. Much of the research often assumes that bailed-out eurozone countries were forced to implement specific reforms against their will. However, according to the research of Catherine Moury and al., this statement appears to be false. Indeed, the bailed-out governments had room to maneuver and the opportunity to exploit the conditionality constraint to their own advantage.[146] According to the authors of this book, bailed-out governments are able to derive political benefits from these operations during and after the program by influencing the policies implemented according to their preferences. Ultimately, national policies remain essential, even in an era of Europeanization.[147] In addition, in some cases, conditionality programs have given countries the opportunity to adopt reforms that were considered necessary but difficult to implement.

See also

- 2000s commodities boom

- 2008–11 Icelandic financial crisis

- Crisis situations and protests in Europe since 2000

- European sovereign-debt crisis: List of acronyms

- European sovereign-debt crisis: List of protagonists

- Federal Reserve Economic Data FRED

- Financial crisis of 2007–08

- Global recession

- Late-2000s recession in Europe

- List of countries by credit rating

References

- Lewis, Michael (2011). Boomerang: Travels in the New Third World. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08181-7.

- Lewis, Michael (26 September 2011). "Touring the Ruins of the Old Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- "NPR-The Giant Pool of Money-May 2008". Thisamericanlife.org. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Heard on Fresh Air from WHYY (4 October 2011). "NPR-Michael Lewis-How the Financial Crisis Created a New Third World-October 2011". Npr.org. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Lewis, Michael (April 2009). "Wall Street on the Tundra". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

In the end, Icelanders amassed debts amounting to 850 percent of their G.D.P. (The debt-drowned United States has reached just 350 percent.)

- Feaster, Seth W.; Schwartz, Nelson D.; Kuntz, Tom (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-A Spectators Guide to the Euro Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012 – via nytimes.com.

- XAQUÍN, G.V.; McLean, Alan; Tse, Archie (22 October 2011). "NYT-It's All Connected-An Overview of the Euro Crisis-October 2011". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "The Economist-No Big Bazooka-29 October 2011". The Economist. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Story, Louise; Landon Thomas Jr; Schwartz, Nelson D. (14 February 2010). "Wall St. Helped to Mask Debt Fueling Europe's Crisis". The New York Times. New York. pp. A1. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Merkel Slams Euro Speculation, Warns of 'Resentment' (Update 1)". BusinessWeek. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Knight, Laurence (22 December 2010). "Europe's Eastern Periphery". BBC. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "PIIGS Definition". investopedia.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- Riegert, Bernd. "Europe's next bankruptcy candidates?". dw-world.com. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- Philippas, Nikolaos D. Ζωώδη Ένστικτα και Οικονομικές Καταστροφές (in Greek). skai.gr. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- Featherstone, Kevin (23 March 2012). "Are the European banks saving Greece or saving themselves?". Greece@LSE. LSE. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "Greek aid will go to the banks". Die Gazette. Presseurop. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- Whittaker, John (2011). "Eurosystem debts, Greece, and the role of banknotes" (PDF). Lancaster University Management School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Reich, Robert (10 May 2011). "Follow the Money: Behind Europe's Debt Crisis Lurks Another Giant Bailout of Wall Street". Social Europe Journal. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Janssen, Ronald (28 March 2012). "The Mystery Tour of Restructuring Greek Sovereign Debt". Social Europe Journal. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- Roubini, Nouriel (7 March 2012). "Greece's Private Creditors Are the Lucky Ones". Financial Times. The A-List. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- "How the Euro Zone Ignored Its Own Rules". Der Spiegel. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Verhelst, Stijn. "The Reform of European Economic Governance : Towards a Sustainable Monetary Union?" (PDF). Egmont – Royal Institute for International Relations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Public Finances in EMU – 2011" (PDF). European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Lowenstein, Roger (27 April 2008). "Moody's – Credit Rating – Mortgages – Investments – Subprime Mortgages – New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Kirchgaessner, Stephanie; Sieff, Kevin. "Moody's chief admits failure over crisis". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Iceland row puts rating agencies in firing line | Business". Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Ratings agencies admit mistakes". BBC News. 28 January 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Waterfield, Bruno (28 April 2010). "European Commission's angry warning to credit rating agencies as debt crisis deepens – Telegraph". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Wachman, Richard (28 April 2010). "Greece debt crisis: the role of credit rating agencies". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Greek crisis: the world would be a better place without credit rating agencies – Telegraph Blogs". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 28 April 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Are the ratings agencies credit worthy?". CNN.

- "Crisis in Euro-zone—Next Phase of Global Economic Turmoil". Competition master. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Thomasson, Emma (27 July 2012). "Tougher euro debt ratings stoke downward spiral – study". Reuters. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Luke, Baker (6 July 2011). "UPDATE 2-EU attacks credit rating agencies, suggests bias". Reuters.

- "Moody's downgrades ANA-Aeroportos de Portugal to Baa3 from A3, review for further downgrade". Moodys.com. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Moody's downgrades EDP's rating to Baa3; outlook negative". Moodys.com. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Moody's downgrades REN's rating to Baa3; keeps rating under review for downgrade". Moodys.com. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Moody's downgrades BCR to Baa3, under review for further downgrade". Moodys.com. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Elliott, Larry; Inman, Phillip (14 January 2012). "Eurozone in new crisis as ratings agency downgrades nine countries". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- Watt, Nicholas; Traynor, Ian (7 December 2011). "David Cameron threatens veto if EU treaty fails to protect City of London". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- M. Nicolas J. Firzli, "A Critique of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision" Revue Analyse Financière, 10 Nov 2011/Q1 2012

- "EUROPA – Press Releases – A turning point for the European financial sector". Europa (web portal). 1 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "ESMA". Europa (web portal). 1 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "EU erklärt USA den Ratingkrieg". Financial Times Deutschland. 23 June 2011. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- Matussek, Katrin (23 June 2011). "ESMA Chief Says Rating Companies Subject to EU Laws, FTD Reports". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- "FT.com / Europe – Rethink on rating agencies urged". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "EU Gets Tough on Credit-Rating Agencies". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "European indecision: Why is Germany talking about a European Monetary Fund?". The Economist. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Eder, Florian (20 January 2012). "Bonitätswächter wehren sich gegen Staatseinmischung work". Die Welt. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Non-profit credit rating agency challenge". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Firzli, M. Nicolas, and Bazi (2011). "Infrastructure Investments in an Age of Austerity : The Pension and Sovereign Funds Perspective". Revue Analyse Financière. 41 (Q4): 19–22. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Euro zone rumours: There is no conspiracy to kill the euro". The Economist. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Elliot, Larry (28 January 2010). "No EU bailout for Greece as Papandreou promises to "put our house in order"". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Kollmeyer, Barbara (15 February 2010). "Spanish secret service said to probe market swings". MarketWatch. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Hewitt, Gavin (16 February 2010). "Conspiracy and the euro". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "A Media Plot against Madrid?: Spanish Intelligence Reportedly Probing 'Attacks' on Economy". Der Spiegel. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Roberts, Martin (14 February 2010). "Spanish intelligence probing debt attacks-report". Reuters. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Cendrowicz, Leo (26 February 2010). "Conspiracists Blame Anglo-Saxons, Others for Euro Crisis". Time. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Tremlett, Giles (14 February 2010). "Anglo-Saxon media out to sink us, says Spain". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Spain and the Anglo-Saxon press: Spain shoots the messenger". The Economist. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Papandreou says Greece is corrupt - FT.com". Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Greece tests the limit of sovereign debt as it grinds towards slump". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022.

- O'Grady, Sean (2 March 2010). "Soros hedge fund bets on demise of the euro". The Independent. London. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Stevenson, Alex (2 March 2010). "Soros and the bullion bubble". FT Alphaville. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Donahue, Patrick (23 February 2010). "Merkel Slams Euro Speculation, Warns of 'Resentment'". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on 26 February 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Connor, Kevin (27 February 2010). "Kevin Connor: Goldman's Role in Greek Crisis Is Proving Too Ugly to Ignore". Huffington Post. USA. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Clark, Andrew; Stewart, Heather; Moya, Elena (26 February 2010). "Goldman Sachs faces Fed inquiry over Greek crisis". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Wearden, Graeme (19 May 2010). "European debt crisis: Markets fall as Germany bans 'naked short-selling'". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- Wray, L. Randall (25 June 2011). "Can Greece survive?". New Economic Perspectives. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Godley, Wynne (8 October 1992). "Maastricht and All That". London Review of Books. 14 (19).

- Feldstein, Martin. "The Failure of the Euro". Foreign Affairs (January/February 2012). Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Euro Plus Monitor 2011". The Lisbon Council. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Ricci, Luca A., "Exchange Rate Regimes and Location", 1997

- Roubini, Nouriel (28 June 2010). "Greece's best option is an orderly default". Financial Times. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- M. Nicolas J. Firzli, "Greece and the Roots the EU Debt Crisis" The Vienna Review, March 2010

- "FT.com / Comment / Opinion – A euro exit is the only way out for Greece". Financial Times. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Greece's Debt Crisis, interview with L. Randall Wray, 13 March 2010". Neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "I'll buy the Acropolis" by Bill Mitchell, 29 May 2011

- Kashyap, Anil (10 June 2011). "Euro May Have to Coexist With a German-Led Uber Euro: Business Class". Bloomberg. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "To Save the Euro, Germany Must Quit the Euro Zone" Archived 4 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Marshall Auerback Archived 8 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 25 May 2011

- Forelle, Charles (19 May 2012). "In European Crisis, Iceland Emerges as an Island of Recovery". The Wall Street Journal.

- Harris, Lee (17 May 2012). "The Hayek Effect: The Political Consequences of Planned Austerity". The American. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Jolis, Anne (19 May 2012). "The Swedish Reform Model, Believe It or Not". The Wall Street Journal.

- Auerback, Marshall (25 May 2011). "To Save the Euro, Germany has to Quit the Euro Zone". Wall Street Pit. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- Demetriades, Panicos (19 May 2011). "It is Germany that should leave the eurozone". Financial Times. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- Joffe, Josef (12 September 2011). "The Euro Widens the Culture Gap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Rogers, Jim (26 September 2009). "The Largest Creditor Nations Are in Asia". Jim Rogers Blog. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Mattich, Alen (10 June 2011). "Germany's Interest Rates Have Become a Special Case". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (17 July 2011). "A modest proposal for eurozone break-up". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Anand. M.R, Gupta.G.L, Dash, R. The Euro Zone Crisis Its Dimensions and Implications. January 2012.

- Erlanger, Steven (20 May 2012). "Greek Crisis Poses Unwanted Choices for Western Leaders". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

But while Europe is better prepared for a Greek restructuring of its debt – writing down what is currently held by states and the European bailout funds – a Greek departure is likely to be seen as the beginning of the end for the whole euro zone project, a major accomplishment, whatever its faults, in the postwar construction of a Europe "whole and at peace."

- Czuczka, Tony (4 February 2011). "Merkel makes Euro Indispensable Turning Crisis into Opportunity". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- MacCormaic, Ruadhan (9 December 2011). "EU risks being split apart, says Sarkozy". Irish Times. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- "Spanish commissioner lashes out at core eurozone states". EUobserver. 9 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Fraher, John (9 September 2011). "Trichet Loses His Cool at Prospect of Deutsche Mark's Revival in Germany". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "The Choice". The Economist. 26 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Douthat, Ross (16 June 2012). "Sympathy for the Radical Left". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

This would effectively turn the European Union into a kind of postmodern version of the old Austro-Hungarian empire, with a Germanic elite presiding uneasily over a polyglot imperium and its restive local populations.

- Soros, George. "Does the Euro Have a Future? by George Soros | The New York Review of Books". Nybooks.com. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Cowie, Ian (16 May 2012). "How would a euro collapse hit us in the pocket?". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Greece must deny to pay an odious debt". CADTM.org. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Debtocracy (international version). ThePressProject. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Kitidē, Katerina; Vatikiōtēs, Lēōnidas; Chatzēstephanou, Arēs (2011). Debtocracy. Ekdotikos organismōs livanē. p. 239. ISBN 9789601424095. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Simkovic, Michael (2009). "Secret Liens and the Financial Crisis of 2008". American Bankruptcy Law Journal. 83: 253. SSRN 1323190.

- "Michael Simkovic, Bankruptcy Immunities, Transparency, and Capital Structure, Presentation at the World Bank, 11 January 2011". Ssrn.com. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1738539. S2CID 153617560. SSRN 1738539.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Simkovic, Michael (January 2010). "Michael Simkovic, Paving the Way for the Next Financial Crisis, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2010". Ssrn.com. SSRN 1585955.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Greece not alone in exploiting EU accounting flaws". Reuters. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- "Greece is far from the EU's only joker". Newsweek. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "The Euro PIIGS out". Librus Magazine. 22 October 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "'Creative accounting' masks EU budget deficit problems". Sunday Business. 26 June 2005. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "How Europe's governments have enronized their debts". Euromoney. September 2005. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Italy faces restructured derivatives hit". Financial Times. 26 June 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "UK Finances: A Not-So Hidden Debt". eGovMonitor. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Butler, Eamonn (13 June 2010). "Hidden debt is the country's real monster". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Newmark, Brooks (21 October 2008). "Britain's hidden debt". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "The Hidden Debt Bombshell" (PDF). Pointmaker. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Wheatcroft, Patience (16 February 2010). "Time to remove the mask from debt". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Brown accused of 'Enron accounting'". BBC News. 28 November 2002. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "IMF calls for bank guarantees to be included in the national debt". Gold made simple News. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "'Hidden' debt raises Spain bond fears". Financial Times. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Portfolio: Falsified Deficit Statistics in Europe". Leaksfree.com. 27 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- "The Hidden American $100 Trillion Debt Problem". Viable Opposition. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Goodman, Wes (30 March 2011). "Bill Gross says US is Out-Greeking the Greeks on Debt". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "Botox and beancounting Do official statistics cosmetically enhance America's economic appearance?". The Economist. 28 April 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Cox and Archer: Why $16 Trillion Only Hints at the True U.S. Debt". The Wall Street Journal. 28 November 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Germany's enormous hidden debt". Presseurop. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Vits, Christian (23 September 2011). "Germany Has 5 Trillion Euros of Hidden Debt, Handelsblatt Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Finger-wagging Germany secretly accumulating trillions in debt". Worldcrunch/Die Welt. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- "Finland Collateral Demands Threaten Bailout Solidarity". The Wall Street Journal. 19 August 2011.

- Schneeweiss, Zoe, and Kati Pohjanpalo, "Finns Set Greek Collateral Trend as Austria, Dutch, Slovaks Follow Demands", Bloomberg, 18 August 2011 9:41 am ET.

- "Finland and Greece agree on collateral". 17 August 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- "Finnish win Greek collateral deal". European Voice. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Marsh, David, "German OK only small step in averting Greek crisis", MarketWatch, 3 October 2011, 12:00 am EDT. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- "The second Greek bailout: Ten unanswered questions" (PDF). Open Europe. 16 February 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "Yle: Suomalaisvirkamiehet salaa neuvomaan Italiaa talousasioissa" [YLE: Finnish officials secretly advised the Italian financial matters] (in Finnish). Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Ομολογία Σταϊκούρα στη Βουλή: "Στα 320 δισ. ευρώ το χρέος το 2013"". TA NEA. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "For hard-hit Greeks, IMF mea culpa comes too late". Reuters. 6 June 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Lagarde: IMF's Admission of Error on Fiscal Multipliers for Greece "A Matter of Honour"". Capital.gr. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Moury, Catherine; Ladi, Stella; Cardoso, Daniel; Gago, Angie (2021). Capitalising on constraint: Bailout politics in Eurozone countries (Manchester University Press ed.). doi:10.7765/9781526149893. ISBN 978-1526149886. S2CID 240025813. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Moury, Catherine; Ladi, Stella; Cardoso, Daniel; Gago, Angie (2021). Capitalising on constraint: Bailout politics in Eurozone countries (Manchester University Press ed.). doi:10.7765/9781526149893. ISBN 978-1526149886. S2CID 240025813. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2018). L'Euro : Comment la monnaie unique menace l'avenir de l'Europe (Les Liens qui libèrent ed.). ISBN 978-2330097059.

- Varoufakis, Yanis (2017). Conversations entre adultes : Dans les coulisses secrètes de l'Europe (Les Liens qui Libèrent ed.). ISBN 978-2330117634.

- Alogoskoufis, George (21 March 2021). "Greece Before and After the Euro: Macroeconomics, Politics and the Quest for Reforms". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3801659. S2CID 233622483.

- Blanchard, Olivier. "Grèce : bilan des critiques et perspectives d'avenir". Fonds Monétaire International. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Aglietta, Michel; Baudry, Sonia; Busson, Henri (2012). "L'austérité est-elle la solution à la crise ?". Regards croisés sur l'économie. 11: 78. doi:10.3917/rce.011.0078.

- Olivier, Blanchard (February 2019). "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w25621.

- Moury, Catherine; Ladi, Stella; Cardoso, Daniel; Gago, Angie (2021). Capitalising on constraint: Bailout politics in Eurozone countries (Manchester University Press ed.). doi:10.7765/9781526149893. ISBN 978-1526149886. S2CID 240025813. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- Moury, Catherine; Ladi, Stella; Cardoso, Daniel; Gago, Angie (2021). Capitalising on constraint: Bailout politics in Eurozone countries (Manchester University Press ed.). doi:10.7765/9781526149893. ISBN 978-1526149886. S2CID 240025813. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

External links

- The EU Crisis Pocket Guide by the Transnational Institute in English (2012) – Italian (2012) – Spanish (2011)

- 2011 Dahrendorf Symposium – Changing the Debate on Europe – Moving Beyond Conventional Wisdoms