Stavudine

Stavudine (d4T), sold under the brand name Zerit among others, is an antiretroviral medication used to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.[3] It is generally recommended for use with other antiretrovirals.[3] It may be used for prevention after a needlestick injury or other potential exposure.[3] However, it is not a first-line treatment.[3] It is given by mouth.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zerit |

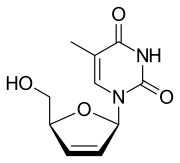

| Other names | 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a694033 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >80% |

| Protein binding | Negligible |

| Metabolism | Kidney elimination (~40%) |

| Elimination half-life | 0.8–1.5 hours (in adults) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.169.180 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H12N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 224.216 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include headache, diarrhea, vomiting, rash, and peripheral nerve problems.[3] Severe side effects include high blood lactate, pancreatitis, and an enlarged liver.[3] It is not generally recommended in pregnancy.[3] Stavudine is in the nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) class of medication.[3]

Stavudine was first described in 1966 and approved for use in the United States in 1994.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[3]

Medical uses

Stavudine is used in the treatment of HIV-1 infection, but is not a cure. It is not normally recommended as initial treatment.[5] Stavudine can also reduce the risk of developing HIV-1 infection after coming into contact with the virus either at work (e.g., needlestick) or through exposure to infected blood or other bodily fluids.[6] It is always used in combination with other HIV medications for the better control of the infection and a reduction in HIV complications.[7]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends stavudine to be phased out to due to its high toxicity levels. If the drug must be used, it is recommended to use low dosages to reduce the occurrence of side effects; however, a 2015 Cochrane review found no clear advantage between high and low dosage regimens.[8]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Stavudine has been demonstrated to affect the fetus in animal studies but no data are available from human studies.[1] Pregnant women should therefore be given stavudine only if the potential benefits outweigh the potential harm to the fetus. Additionally, there have been case reports of fatal lactic acidosis in pregnant women receiving combination therapy of stavudine and didanosine with other antiviral agents.[1]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that HIV-infected mothers not breastfeed their infants, in order to avoid the risk of HIV transmission through breast milk.[9] There is also evidence that stavudine gets into animal breast milk, although no data are available for human breast milk.[1]

Children

Stavudine is safe for use in children infected with HIV from birth through adolescence. Adverse effects and safety profile are the same as adults.[1]

Elderly

There is no data available for stavudine use in HIV-infected adults aged 65 years or older. However, among 12,000 people over the age of 65, 30% developed peripheral neuropathy.[1] Additionally, since the elderly are more likely to have decreased renal function, they are more likely to develop toxic side effects.[10]

Adverse events

Common side effects[1]

Severe side effects[1]

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Lactic acidosis

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatotoxicity

- Hepatomegaly with steatosis

- Lipoatrophy/lipodystrophy (fat redistribution/accumulation)

Individuals are monitored for the development of these serious adverse effects. The development of peripheral neuropathy is shown to be dose related, and may be resolved if the drug is discontinued. Individuals with advanced HIV-1 disease, a history of peripheral neuropathy, or individuals on other drugs that have association with neuropathy develop this side effect more often.[1]

Stavudine has been shown in laboratory test to be genotoxic, but with clinical doses its carcinogenic effects are non-existent. Hyperlactatemia, bone mineral density (BMD) loss, reduction in limb fat and an increase in triglycerides were found when administered in high dosages. It is also one of the most likely antiviral drugs to cause lipodystrophy, and for this reason it is no longer considered an appropriate treatment for most patients in developed countries.

HLA-B*4001 may be used as a genetic marker to predict which patients will develop stavudine-associated lipodystrophy, to avoid or shorten the duration of stavudine according to a study in Thailand.[11]

It is still used as first choice in first line therapy in resource poor settings such as in India. Only in case of development of peripheral neuropathy or pregnancy is it changed to the next choice, zidovudine. Safety and effectiveness of dosage titration was not reported in treatment naive patients. It was only reported in those patients with sustained virologic suppression. These findings are not generalized to Stavudine used in ART naive patients who have high viral loads.

On Monday 30 November 2009, the World Health Organization stated that "[The WHO] recommends that countries phase out the use of Stavudine, or d4T, because of its long-term, irreversible side-effects. Stavudine is still widely used in first-line therapy in developing countries due to its low cost and widespread availability. Zidovudine (AZT) or tenofovir (TDF) are recommended as less toxic and equally effective alternatives."[12]

Mechanism of action

Stavudine is a nucleoside analog of thymidine. It is phosphorylated by cellular kinases into an active triphosphate. Stavudine triphosphate inhibits HIV's reverse transcriptase by competing with the natural substrate, thymidine triphosphate. Reverse transcriptase is the enzyme the virus uses to make a DNA copy of its RNA in order to insert its genetic material into the host's DNA. Upon incorporation into the DNA strand, stavudine triphosphate causes termination of DNA replication.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption: Stavudine has rapid absorption and good oral bioavailability (F = 0.86).[7]

Distribution: Stavudine does not bind to proteins in the blood.[7]

Metabolism: The clearance of stavudine is affected minimally by hepatic metabolism. Oxidation and glucuronidation produce minor metabolites.[7]

Elimination: Stavudine is mostly eliminated in the urine and mostly in its unchanged form.[7]

Drug interactions

Simultaneous use of zidovudine is not recommended, as it can inhibit the intracellular phosphorylation of stavudine. Other anti-HIV drugs do not possess this property.

Stavudine is not protein-bound nor does it inhibit the major cytochrome P450 isoforms. Thus, significant drug interactions with drugs metabolized through these pathways or drugs that are protein-bound are unlikely.[7]

History

Stavudine was first created by Jerome Horwitz in the 1960s and was originally named D4T.[13] When the AIDS epidemic occurred in the 1980s, William Prusoff and Dr. Tai-Shun Lin at Yale University discovered the anti-HIV properties of Stavudine.[14]

In 1990 Yale patented the use of the drug stavudine (d4T) to treat HIV, and granted an exclusive license to Bristol-Myers Squibb to manufacture the drug under the trade name Zerit.[14] Since then, stavudine became a key drug for treating HIV. However, because of its high price (over $1600 per year) Zerit was inaccessible to most patients in developing countries. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) found an Indian manufacturer, who was willing to sell stavudine in South Africa for $40 per year per patient. However, this deal fell apart, because Yale patented stavudine in South Africa, and it was unwilling to issue a license to the indian generic manufacturer. Two Yale students (Amy Kapczynski (now a Yale law professor) and Marco Simons) sided with Médecins Sans Frontières and approached Yale with idea to put pressure on Bristol-Myers Squibb to lower Stavudin's prices in South Africa and/or to issue patent licenses to generic manufacturers. After the issue was publicized in the New York Times, Bristol-Myers Squibb announced, that it would not enforce the stavudine patent in South Africa, and that it would sell Zerit in sub-Saharan Africa for $55 per year.[15]

Stavudine was the first drug to be granted parallel track status in 1992, by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which allowed for the agency to make Stavudine available to patients before being approved. Stavudine was submitted under the FDA's accelerated approval process. Through this process, Stavudine's effectiveness was measured by its effect on the surrogate marker, CD4, instead of clinical endpoints. The FDA concluded that an increase in CD4 cell counts was an indicator of how effective the drug would be against AIDS and HIV infection. Stavudine was the fourth drug to be approved for the treatment of AIDS and HIV infection by the FDA on June 27, 1994. Even after approval, studies were continued to evaluate the clinical benefit of the drug. If there is no indication of clinical benefits, the accelerated approval may be withdrawn.[16]

In 2018, Mylan Pharmaceuticals discontinued manufacturing stavudine 20 mg, 30 mg, and 40 mg capsules.[17]

References

- "Stavudine capsule". DailyMed. 21 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Zerit EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Stavudine Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 505. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "Updated Guidelines for Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV—United States, 2016" (PDF). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents" (PDF). Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 14 July 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Zerit (stavudine) capsules and powder for oral solution prescribing information" (PDF). Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb. December 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-01-31.

- Magula N, Dedicoat M (January 2015). "Low dose versus high dose stavudine for treating people with HIV infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD007497. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007497.pub2. PMID 25627012.

- "Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children | Gender | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.CDC.gov. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "FDA Guideline for Industry: Geriatric Population" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. August 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2016.

- Wangsomboonsiri W, Mahasirimongkol S, Chantarangsu S, Kiertiburanakul S, Charoenyingwattana A, Komindr S, et al. (February 2010). "Association between HLA-B*4001 and lipodystrophy among HIV-infected patients from Thailand who received a stavudine-containing antiretroviral regimen". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (4): 597–604. doi:10.1086/650003. PMID 20073992.

- "New HIV recommendations to improve health, reduce infections and save lives". World Health Organization. November 30, 2009. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010.

- "Jerome Horwitz Obituary". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- Prusoff W (2001-03-19). "The Scientist's Story". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- Ouellette LL (September 2010). "How Many Patents Does It Take To Make a Drug? Follow-On Pharmaceutical Patents and University Licensing". Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review. 17 (1): 299–336.

- "FDA Approval of Stavudine (d4T) | News | AIDSinfo". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

- "Stavudine". Discontinuations Reported to FDA. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 30 April 2018.

External links

- "Stavudine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.