Daniël Goulooze

Daniël "Daan" Goulooze (28 April 1901 – 10 September 1965) was a Dutch Jewish construction worker who was a committed communist and resistance fighter.[1] In 1925, he became a member of the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN) and by 1930 had become an executive member of the organisation. In 1934, he formed Pegasus, a publisher of many left-wing writers and intellectuals in the Netherlands, some for the first time. In 1935–1936, Goulooze formed the Dutch Information Service (DIS), an organisation that supplied information to the Soviet Union.[2] Goulooze become the liaison between the organisation and the CPN.[2] In 1937, he went to the Soviet Union, where he received intelligence training at the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute in Moscow.[2] Upon returning, he became the liaison officer of Communist International (Comintern) in the Netherlands, his main duty being to maintain on-going radio contact with Soviet intelligence.[3][4][5]

Daan Goulooze | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Daan Goulooze, taken in 1955 | |

| Born | 28 April 1901 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Died | 10 September 1965 (aged 64) Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Occupation(s) | construction worker, Comintern agent |

| Organization(s) | Communist Party of the Netherlands, Comintern, Red Orchestra |

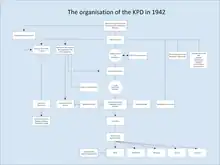

Goulooze used the DIS organisation from early 1937 to help establish Soviet Red Orchestra agents in the Netherlands, France and the Low Countries. After the start of the war and the occupation of the Netherlands, Goulooze helped to reestablish the KPD in Germany in 1940. As the war progressed, the Comintern, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the French Communist Party were progressively destroyed in Europe, the DIS designed to send intelligence to Moscow, became increasingly important to Soviet intelligence as the only organisation in Western Europe, where they could maintain contact with Soviet agents on the ground.[6]

Such was the level of communication that Goulooze conducted with Soviet intelligence, that he maintained four separate and active wireless telegraphy sets and one in reserve.[1] His signals were eventually detected by the German Funkabwehr and he was arrested along with many members of the DIS. Goulooze was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp but managed to survive the war. In 1948 he was expelled from the CPN[3] after a smear campaign about his role in the war that last more than a decade. He then worked for the "De Republiek der Letteren" (The Republic of Arts), a left-wing publishing house. In 1951 he had a heart attack and died in 1965.[5] Goulooze used the Daan alias disguise his identity.

Life

Goulooze was the son of Daniël Goulooze, a blacksmith, and Baukje Goulooze (née Visser), a housemaid, and was the oldest of six children, who grew up in Amsterdam in a working-class family.[5] His grandparents on his father's side came from Zeeland in the south, and on his mother's side from Friesland, in the northern part of the Netherlands.[5] His father was a member of the National Federation of Metal Workers union that was affiliated with the National Labor Secretariat (NAS, Nationaal Arbeids-Secretariaat) trade union federation. He was an admirer of the Dutch politician and later social anarchist Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis.[5] After the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940, his father was interred at the Herzogenbusch concentration camp and died, aged 70, in 1943.[5]

In March 1929, Goulooze entered into a common-law marriage with Lydia Wolters.[5] In October 1938, Goulooze and Wolters split. Goulooze entered into his common-law marriage, this time to Petronella Alida van de Plaats (1911-1949), who suffered from poor health. The couple had a son, Zane, born in 1939, to whom the couple were devoted. To protect them, Goulooze moved them to Gooi at the start of the war.[7]

Anarchism

After leaving school, Goulooze was apprenticed to a carpenter and attended an evening school to supplement his knowledge of carpentry. Politically, as a youth, Goulooze was leftist and this was visible by his youth membership of the National Labor Secretariat (NLR, Nationaal Arbeids-Secretariaat). He subsequently worked in the drawing school of the Dutch shipbuilding company, Nederlandsche Scheepsbouw Maatschappij in construction.[5]

In 1916, Goulooze joined the Social-Anarchist Youth Organisation (SAJO, Sociaal-Anarchistische Jeugd Organisatie).[8] his was an organisation that was established in several cities including Amsterdam, that consisted of several dozen young rebellious people who refused to do their military service, instead, spending their time going on rambles, and making music as well as planning bombings.[9]

In 1919, Goulooze was elected treasurer.[5] In September 1920, Goulooze took over administration for publishing the organisations magazine, De Opstandeling (The Insurgent).[10] Around this time, Goulooze became part of a group of young men and women,[11] that formed around Dutch communist and chemigrapher Jan Postma.[12]

Postma would go camping with the group, and they would hold discussions and debate politics, communism, trade unionionism and the Russian Revolution. Postma strongly supported trade unionism, the soviet revolution, dictatorship for the proletariat and the group initially shared his enthusiasm, but some eventually rejected his views. Goulooze for the most part, found himself in agreement with Postma and this, in turn, developed into a lifelong friendship. The heated debates eventually led to a group withdrawing from the SAJO that included Goulooze, leaving to join the Federation of Social Anarchists of which Postma was a member. On 22 July 1922, Goulooze became the administrator for the Social Anarchists magazine, De Toekomst. [13]

Nomad

The first real decision he made was whether to accept military service during conscription or refuse it.[14] As an anarchist, Goulooze was anti-militaristic and while it was accepted for members of his peer group to refuse the service and wait to be arrested by the Military police, he decided to ignore the conscription order and evade arrest. Goulooze became a nomad, living on his wits, constantly on his guard. During this period, he worked in Antwerp, among other places. For several years he managed to avoid being arrested. In 1929, when he moved into his own apartment with his wife, he refused to be added to the Electoral roll.[14]

However, it became expedient in the early 1930s[5] for Goulooze to rebuild his legal existence and he was finally arrested. However, when he was undergoing his medical examination for conscription, he was rejected due to a minor foot disorder, making the whole exercise moot.[14]

Living a nomadic life did not prevent Goulooze from taking part in a number of political actions in the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1923, Goulooze was responsible for the transportation and distribution of the special newspaper De Spelbreker, not only in Amsterdam, but in the rest of the country.[15]

The De Spelbreker newspaper was created by the Committee of Action, a group of the Dutch labour movement, made up of Communists, Syndicalists and Anarchists, who wanted to protest the 1923 Fleet Act and the 25th anniversary of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. During this period, Goulooze was also working for the NAS. His name appeared in De Arbeid, the legal body of trade union on 17 November 1923.[15]

In the same year, the NAS split into two groups. On one side were 8,000 members who left to found the IWA-affiliated Dutch Syndicalist Trade Union Federation (NSV, Dutch: Nederlands Syndicalistisch Vakverbond) that was chaired by Bernard Lansink. On the other was a group who wanted to join the Red International of Labour Unions (RILU), although many in the federation favoured the anarcho-syndicalist International Workers' Association (IWA). Goulooze sided with the NSV and became the organiser of a youth recruitment office at a Local Labour Secretariat (PAS, Plaatselijke Arbeids Secretariaten) in Amsterdam.[16]

Communist Party of Netherlands

In June 1924, the Federation of Social Anarchists group came to an end.[15] At the time, Goulooze rejected anarchism, along with the Postma group. He became fully Communist, as it was the only political alternative that suited his worldview. Goulooze believed that the anarchists were incapable of an effective struggle against capitalism.[17] Unwilling to join the CPN, he, along with Postma, instead joined the BKSP on 24 January 1925. Postma went on to become editor of De Kommunist, the magazine of the BKSP. [18]

Six months later, the BKSP party leadership split, David Wijnkoop along with most of the leadership was forced to resign and a large sector of BKSP opted to rejoin the Communist Party of Holland ("Communistisch Party Holland") (CPH).[12] By 1925, Goulooze had become an active communist and in 1926, became a member of the CPH.[19] Due to his age, Goulooze became an active member of the Young Communist League (CJB, 'Communistische Jongeren Beweging). Goulooze became a popular and later important member of the CJB. Under Goulooze and in agreement with the political line take by the Young Communist International (KJI, Kommunist Jeugd Internationale) the CJB decided to take direct action, instead of the usual discussion of politics.[20]

Under orders from Moscow, it was rearranged into business divisions and the magazine De Jonge Communist (The Young Communist) was renamed to De Jonge Arbeider (The Young Worker).[20] As the CJB was a small organisation, Goulooze tried to create a leadership role that resulted in him negotiating with several companies during spontaneous youth strikes. At the same time, a plan grew to send a delegation to the Soviet Union.[21] Seven young people were delegated from suitable companies and the delegation left at the end of August 1926. When the group returned, a detailed brochure, What did 7 young workers in Soviet Russia see?, was published that described their impressions.This was the first of many trips to the Soviet Union he would take.[21]

A new academy

When he returned, Goulooze established a new academy that offered a three-week course to train a cadre of CJB communists. The leaders of the academy were made up of Henriette Roland Holst, Gerrit Mannoury, and Henk Sneevliet and its initial enrollment consisted of sixteen students, aged sixteen to twenty-five.[21] When the academy came to public notice, Goulooze defended it existence, but also took an active part in running the different CJB departments that included canvassing, leafletting, pasting up posters and demonstrating.[22]

In June 1928 in Amsterdam at the CPH party congress, the congress erupted in open warfare. Goulooze was immediately elected as secretary of the board, where he represented the CJB.[23] On 17 August 1928, Goulooze attended the World Youth Peace Congress as a representative of the CJB, that was hosted in Eerde.[24]

Propaganda efforts

During this period Goulooze acted to ensure that communist propaganda in the form of the newspapers Op de bon and Het Panster reached every part of the Royal Netherlands Army. A special propaganda stunt was the publication of military booklet by the officer Jan Zonderland, that contained a worker's oath. The case gained national attention, due the commotion from baggage searches in barracks to remove it; that it came to the notice of the national press, the daily newspaper Het Leven.[25]

Reforming the International Workers Aid

In 1930, the International Workers Aid (IAH, Internationale Arbeiders hulp) that existed to provide aid to strikers and strengthen cultural ties with the Soviet Union, became embroiled in a disagreement amongst its members, that degenerated into a fight. Goulooze was ordered to take over the reconstruction of the IAH and oversee the election of a new board.[26]

CPN Board member

The Great Depression exacerbated the political problems faced by the CPN. The Comintern believed it would result in revolution in the Netherlands. Members of the CPN were in favour of the Comintern attitude, that saw Social Democrats, the main political fulcrum of the ruling class, as the main obstacle to the establishment of a proletarian revolution.[27] The Comintern classed them as "social fascists" who had to be fought at all costs; they were the enemy. Goulooze, who was centrist, rejected this view. At a meeting at his house on 1 February 1930, Richard Gyptner of the Young Communist International, castigated him for this. After a long discussion, the Young Communist League board decided to support the Comintern position. At that point, Goulooze ended his association with the Young Communist League and he was tasked along with four others to organise a conference of CPN members.[28]

In service to the Comintern

In February 1930, a new board was elected at the conference and the membership achieved unity on the basis of political guidelines received from the Comintern. At the age of 24, Goulooze became a member of the CPN and was elected as a CPN board member. He became the secretary of the youth organisation, a position he held for four years.[29]

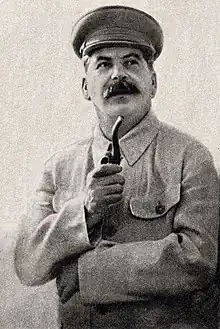

Goulooze was then subsequently elected organisational secretary of the CPN.[30] During this period, it was requested by the party leadership that Goulooze should write on his thoughts and views, now he had a better understanding of the internal functioning of the party. He tried to identify those who are not following the Stalinist line and advocated for stronger control of party members.[31]

Publishing

Goulooze was given the task of publishing communist brochures and books. His love of writing up to that point was known in the Party and he achieved a level of published work for the organisation that has not been reached since.[32]

In 1927, he wrote De grondslagen van het communisme, de taak van de (the foundations of communism, the task of the communist youth), followed by the 104 page essay on the 1928 KJI Congress.[32] Goulooze considered reading and studying a revolutionary act. Over the next several years, he built up publishing arm of the CPN and imported communist literature from abroad. He also opened a number of communist bookshops.[33]

In 1933, he established the Amstel Agency, a publishing house that was run by Lydia Wolters, his wife. The publishing work was done in his own house. During the early 1930s, he made numerous trips abroad to arrange contracts with writers.[33] In 1932, he published a book by N. Bogdanov, Het eerste meisje; een romantische geschiedenis (The first girl; a romantic history), about life for members in the Komsomol.[34] In March 1934, as the work of publishing at his house was becoming too stressful due to the success of the business, Goulooze established the formal Pegasus publishing house, located at 29 Nieuwe Prinsengracht in Amsterdam. During the course of his work as director, he formed relationships with many leading left-wing intellectuals and new writers and academics in the country.[35] During the period he worked there, Goulooze published The ABC of Communism written by Nikolai Bukharin and Yevgeni Preobrazhensky and the Marxist Library in 24 volumes. These were classic works by writers like Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. These books were generally not available in the Dutch language beforehand, so they sold in large quantities.[36] Among the most important people who ran his publishing house was Hein Kohn, the main driving force in the publishing house as well as Nel Schuitemaker, Martien Beversluis, and Menno Poldervaart.[37]

In 1933, after the uprising in the Dutch De Zeven Provinciën-class cruiser De Zeven Provinciën, the government banned a whole series of left-wing organisations including the CPN.[40] This brought huge scrutiny to the CPN and Goulooze as secretary was made responsible for the security of the organisation. Over the next few months, he built a network of trusted people that were committed to identifying and stopping infiltration by the police, the CIA[5] and other intelligence agencies.[40] Through that work, he became familiar with many members of the Belgian and French Communist parties and the Comintern.[41]

Reichstag fire

On 30 January 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and following the Reichstag fire on 27 February 1933, strengthened his power. The communists and the CPN believed Hitler would fail, in the expectation that they would come to power.[42] Instead, Hitler used the fire as a pretext to launch an attack on Communist and Bolshevist groups in Germany in an attempt to destroy them.[43] At the time, Goulooze was in Berlin and met Georgi Dimitrov, who had been arrested, after being seen talking to Marinus van der Lubbe, who was accused of starting the fire. Goulooze provided information to Dimitrov that ensured his release. Goulooze used the opportunity to print The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror, in the Netherlands that placed the blame for the fire with the Nazis.[44]

In the summer of 1933, Goulooze provided assistance to Johann Wenzel, a GRU agent and radio operator who was part of a Soviet espionage group that operated in Western Europe.[45] Wenzel travelled to the Netherlands with Theodor Bottländer, a German official of the AM Apparat department of the Central Committee of the KPD, to obtain information on Marinus van der Lubbe.[45]

International Red Aid

The International Red Aid (MOPR) was an international social service organization established by the Communist International in 1922.[46] When the Nazis came to power at the end of January 1933, hundreds of German communists made a direct appeal to the MOPR for help. In 1933, it became clear the MOPR was insufficient in design and strength to deal with the number of people who were applying for help. The CPN instructed Jan Postma to expand the organisation.[47]

At the end of 1933, it was given a higher workload when it moved to larger rooms at the Bloemgracht in Amsterdam. It was manned by Piet de Smit who did the secretarial work, Anton Winterink, who was part of the editorial work, and Friedl Baruch, who became the KPD liaison.[5]

Goulooze along with Winterink and many others members of the CPN were involved in raising aid money to buy food and clothing for the refugees[48] at a time when police were actively hostile to the refugees and the banned CPN.[48] The CPN had many enemies outwith the Dutch state and the police, that included enemy agents posing as communists seeking help but there to infiltrate the CPN. That led to the arrest of many genuine communists. Postma worked closely with Goulooze and became responsible for checking the reliability of each refugee in turn.[49] Goulooze's job was to protect the organisation particularly from espionage attempts and the police.[5]

In 1934, the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) established an underground bureau, known as an Abschnittsleitungen in Amsterdam.[50] Goulooze arranged for communists who were working on KPD assignments to travel between the Netherlands and Germany. In the summer of 1939, the relationship between the CPN and KPD deteriorated due to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[51] By May 1940 and the German invasion of the Netherlands, the relationship between the two organisation had completely broken down. Goulooze was the only person to maintain contact with the illegal KPD leadership in Amsterdam.[52]

Comintern

In the period immediately after the Nazis seized power on 30 January 1933, Goulooze made several trips to the Soviet Union, Prague and Paris in the context of reorganising the Comintern.[52] In the same year, the International Liaison Department (OMS) of the Comintern[53] was transferred from Berlin to Amsterdam[54] under the command of Osip Piatnitsky in Amsterdam. [55] The OMS was a part legal, part illegal organisation whose purpose was to carry out administrative policy including arranging travel for officials, to develop and maintain a communication system between the Comintern and the Soviet Union using radio communications and couriers, as well as managing funding for the Comintern organisation and to care for wealthy communists.[55] Goulooze provided the addresses where the Comintern radio transmitters could be housed in Amsterdam.[54] In 1934, Bulgarian Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov was elected secretary of the Comintern and Goulooze became further involved in the daily running of the organisation.[52]

In 1935, with permission from the CPN, he started working primarily for the Comintern, but remained director of the Pegasus publishing house, that he used for cover.[1] In the same period, between 1935 and 1937, Dutch CPN member, August Johannes van Proosdy was recruited by Goulooze and sent for technical training in wireless telegraphy techniques in the Soviet Union.[56]

Dutch Information Service

By 1937, he was completely devolved from the CPN executive.[52] In the same year, Goulooze was ordered by Dimitrov to disband the current OMS in Amsterdam and create a new OMS, with the infrastructure to support communications with Moscow, including new radio operators, electricians and couriers that were to be recruited from the CPN.[54][57] It was completely separate from the former German Comintern.[54][57] Goulooze was provided help by Wenzel, who moved to the Netherlands, in early 1937. Wenzel was an expert radio engineer and they discussed plans for the construction of a radio network in the Netherlands.[58]

As a publisher Goulooze, was able to travel widely without restrictions, that enabled him to meet a wide variety of people, and select particular people for particular jobs.[52] In the same year, he received intelligence training at the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute in Moscow.[2] By April 1939, van Proosdy had built a radio transmitter that was based on the Hartley oscillator. Goulooze knew nothing of how wireless telegraphy worked, so delegated the ciphering and radio transmission to his employees.[59][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2]

In June 1939, Goulooze recruited Adam Nagel, a photographer[60] and communist member of the CPN to work with Wenzel in Belgium.[61] In the same period Goulooze recruited CPN member Jacobus "Co" Dankaart as his deputy in the information service and became the group's treasurer. Dankaart also worked as a cutout between the radio group and Goulooze.[61]

Non aggression pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed in August 1939, defined neutrality between the ideological rivals of Germany and the Soviet Union. However, it created considerable ideological difficulties for the CPN and the Comintern. The Comintern pursued no policy other than what the Soviet government planned. It labeled the global conflagration as an imperialist conflict and rejected the pact.[62]

With the coming of World War II, the ideology of Popular Front and United front were abandoned by communist parties in Europe, and the politics of proletarian class struggle once again became predominant. The French Communist Party were no longer called to defend the French homeland when France declared war on Germany, so was declared a proscribed organisation. [63]

The French government began to persecute Communists in France, leaving the French Comintern, the KPD and Communist Party is disarray.[63] This resulted in Goulooze's organisation becoming increasingly important to Soviet intelligence as the only organisation in Western Europe that could maintain contact with agents on the ground.[6] In the Netherlands, the leadership of the CPN was expanded to cope with the supposed increased work, in fact it was to attempt to balance opposing ideologies on the board.[64] The leadership of the CPN eventually began to disagree with the leadership of the Comintern, their viewpoint becoming diametrically opposed. While the CPN viewed the war as a fight between opposing ideologies, the Comintern believed it was a true power struggle between nations.[65]

Soviet intelligence

In October 1939, Anatoly Gurevich, a Ukrainian GRU agent who was part of a Soviet espionage group that operated in Germany, and Belgium, visited Goulooze to request help to build his espionage network in Belgium.[2] Gurevich asked that a temporary wireless telegraphy link be established for his use, while he established his own wireless telegraphy link in Belgian and this was provided by Goulooze and used, until January 1940.[2] In July 1940, Gurevich again visited Goulooze, his second visit, to request the reserve cypher code,[lower-alpha 3] that Goulooze had received from his visit to the Soviet Union, the year before.[2]

Occupation

After the occupation of the Netherlands by the Wehrmacht that began on 10 May 1940, a meeting was held by the CPN on 15 May 1940, where it was realised that many of the members would not survive the war and the party itself would have to operate illegally.[65] The secretariat was reformed with many members put in reserve with Paul De Groot, Jan Dieters and Lou Jansen forming the triumvirate that gradually brought the illegal CPN into action. During that month, De Groot planned to run the illegal CPN from Moscow and was in contact with Goulooze to arrange passage by ship, but the plan was abandoned when De Groot and Goulooze visited the Soviet trade representative in Netherlands who rejected the idea. [66]

De Groot then expounded the idea of editing and printing an illegal newspaper from Vichy France. Goulooze explored the idea with French and Belgian communists but the plan was found to be impractical and was abandoned. De Groot instructed Goulooze to contact the Comintern executive in Moscow, to make a request for the secretariat to move to Moscow but on 21 June 1940, Dimitrov rejected the idea, informing De Groot that the group had stay in the Netherlands. Dimitrov forwarded detailed instructions to the secretariat on how to resist the occupation.[66]

During the first months of the occupation, individual leaders of the CPN lacked a cohesive approach to resisting the occupation and took a wait-and-see approach on the political front. Goulooze used to time he was contact with the CPN leadership to call for more political activity.[67] From the very beginning Goulooze was in favour of uncompromising and vigorous resistance to the Germans.[5]

During this period, Goulooze was reporting to the Comintern. [67] The reports were created by the CPN party leadership. Due to the limited radio contact, he would first send the reports in an abbreviated form, as well as forwarding each completed report to Moscow by courier.[67] In October 1940, the secretariat complained to Goulooze about a summary letter that Goulooze had written, that was critical of the secretariat, of its wait-and-see approach. In a meeting of the CPN leadership, they decided to replace him after holding a vote that resulted in "no confidence". The secretariat had withdrawn from Amsterdam, leaving the OMS in the city.[68]

Goulooze had stated in the letter than they should have maintained more contact with the OMS in city. The secretariat failed to understand that Goulooze was employed by the Comintern executive directly from Moscow, and had no control over him. De Groot contacted the Comintern executive, who dismissed the idea of replacing him and demanded from that point forward all messages meant for the executive go through Goulooze.[68]

Collaboration

On 24 June 1940, the Dutch government withdrew the CPN publication ban and on 26 June an issue of the "Volksdagblad"[lower-alpha 4] was written.[65] In an article, Paul de Groot opined that German aggression was caused by English imperialism and the Dutch bourgeoisie, stating that the Dutch people had no "enmity" towards the German people and that the Dutch people had "only an interest in friendship and peace with the German people".[65] The article went on by stating:

- "It is in the highest interest of the Dutch population that they neither directly nor indirectly, support the warfare of the Allies, but that they observe a true neutrality towards Germany. Restoring peace and friendship with the German people is the first step that the Dutch people can and must take in the interest of restoring general peace. This also means that the Dutch working people must adopt a correct attitude towards the German occupation of our country"[69]

Goulooze read the "Volksdagblad" article and was vehemently opposed to its printing. He managed to make contact with a Comintern representative, who contacted the Comintern executive in Moscow. They forbade its printing. However, the article was released. At the time, there was some panic in the CPN at the release of the article and how it would be viewed.[69] It did not prevent the CPN and its organs from being banned by the Arthur Seyss-Inquart in July 1940.[70]

Expansion

At the beginning of the occupation, Goulooze had recruited one radio engineer, van Proosdy, whose codename was "Frans".[71] The transmitter was hidden in van Proosdy's house in Orteliusstraat in Amsterdam.[2] In 1938, CPN member Jan de Laar was recruited by Goulooze and sent to the Soviet Union for technical training in wireless telegraphy and intelligence techniques. When de Laar returned he became an assistant to van Proosdy.[2]

In April 1940, van Proosdy built a radio transmitter for use by a woman in south Amsterdam and by February 1941, she had been trained to use it.[72] In total, five radio operators were eventually recruited by Goulooze by the end of 1941.[71] To ensure a high level of security, Goulooze separated the encryption/decryption of messages by the cypher clerks from the radio transmission process and used couriers to move messages around, with messages hidden in matchboxes, flashlight batteries or rolled in cigarette cases. It resulted in the radio operator's never knowing what the contents of their message were and the cypher clerks not knowing who transmitted the telegrams.[73] At the same time, the people in his network were employed in legitimate roles designed to disguise their illegal activity, for example as municipal workers.[73]

Goulooze used low-power shortwave radio transmitters that used the 30-metre band (10.100–10.150 MHz) and that were capable of long-distance traffic.[74] The transmission of telegrams took place at different times. As the war progressed, Goulooze passed on messages from the KPD, the CPN and the Comintern. Information on military activity, e.g. armaments, deployment of units along with industrial activity, e.g. production figures, was increasingly also collected and forwarded.[74]

Request for help

In the summer of 1941, Eugen Fried contacted Goulooze to request his help to expand his radio network in Brussels.[75] Goulooze sent van Proosdy to Brussels in August 1941. van Proosdy was shown a self-built transmitter by the young person who was hosting it, but it refused to work. A new transmitter was delivered by courier to van Proosdy, three weeks later and he managed to make a connection to Moscow.[76]

CPN Resolve

As the CPN recovered after being banned, a second meeting of the triumvirate was arranged in July 1940, where they updated and prepared new manifestos. They decided to force a general strike in the large metal companies in November and protest against the persecution of Jews. At the end of November, the CPN published an edition of the De Waarheid (The Truth).[7]

Goulooze considered the actions too late and was annoyed that the newspaper did not mention the CPN itself.[77] Goulooze, who was in communication with the comintern, was critical of the strike.[78] The comintern sent instructions to direct the goals of the CPN, i.e. not to see their work as proletarian revolution but as a national liberation struggle. The editorials that later appeared in the future versions of the De Waarheid, made the point in clear language, stating it was not about communism, it was about national liberation and return of democratic freedoms.[79] Despite the friction between Goulooze and the executive, the CPN leadership still used Goulooze to pass messages to the Comintern.[80]

Red Orchestra

Much more important for the Soviet Union than the CPN and the triumvirate, was the work undertaken by Goulooze for the KPD.[80] From the outset of the war, Goulooze maintained radio links between the area control centre ("Abschnittsleitung") of the KPD in Amsterdam and the area control centre of the KPD in Paris, the Western European Bureau of the Comintern in Paris and Comintern Executive in Moscow.[81] He also managed the links between the Abschnittsleitung in Amsterdam and illegal groups in Germany. [81] In 1939, the French KPD groups fell into disarray as the French government banned the French communist party and interned many of its members.[81] As a result, radio and courier services were cut. The Comintern used Goulooze to bring these various groups back into contact with each other.[81]

Knöchel Emigre group

At a meeting in Moscow in 1940, it was decided that the various KPD Abschnittsleitung in different capitals in Germany should be dissolved, to enable the formation of a new operational leadership in Germany.[82] The intention was for German KPD organiser, Wilhelm Knöchel[lower-alpha 5] to take change of the KPD in Germany.[82][83] Knöchel who was considered an exceptionally effective communist resistance organiser, whose alias was "Alfred".[84] He had been living in Amsterdam since 1936 and was the leader of an emigre group of German communists. By 1939, he was living in Moscow and was a full member of the Central Committee of the KPD.[85]

To bring this plan into operation, the Comintern decided the planning stage would be done in Amsterdam, which resulted in Knöchel returning to Amsterdam. Together with Willi Gall, Knöchel began publishing communist literature that included various leaflets and bulletins, for example "The Enemy Stands in Your Own Country", for distribution in Berlin.[82] From mid-1940, Knöchel with the assistance of Goulooze began to train the emigre group of communists in the Netherlands to work in Germany as political activists and informers.[86] Goulooze was able to obtain blank identity cards, along with official stamps from a colleague that enabled the KPD members who were hiding, to interact with CPN members in Amsterdam and to travel safely to Germany in some cases under diplomatic protection. At the time, Goulooze received instructions from the Comintern and Swedish Communist Party in Stockholm[87] where the KPD leadership emigrated after they were banned. As the Swedish communists were against setting up a radio transmitter link with Amsterdam, Goulooze organised a courier link by sea and when the sailors visited the sea port of Delfzijl, he would pick up a suitcase full of communist brochures, magazines and other literature. In that manner, the Dutch CPN and KPD members managed to read the latest Russian communist literature. The connection by sea, broke down in late 1941 or early 1942 when many Swiss communists were arrested.[88]

The first KPD member to travel to Germany with Goulooze's identity documents was Alfons Kaps who went as an instructor, in January 1941. The next person to travel was Willi Seng. Albert Kamradt was the third person. The fourth person was Alfred Kowalke.[89] On the 9 January 1942, Knöchel met Goulooze for a final meeting before travelling to Germany, taking along blank identity papers, a selection of official stamps and communist literature, travelling as an itinerant silver polisher. [90] At the time, Goulooze arranged for everything that was published by the Comintern executive in Moscow, to be couriered to Knöchel in Berlin.[91] When he arrived in Berlin, Knöchel started to produce the hectographed "Der Friedenskämpfer" (“The Fighter for Peace,”) that offered detailed accounts of German atrocities across the eastern front.[83] The May 1942 special edition of "Der Friedenskämpfer" included detailed knowledge of the execution of French, Czechs, Germans, and Norwegians across Europe and as well as specific military companies that carried out executions of Soviet POWs in Leningrad, and civilians in Lviv. Knöchel exchanged documents in the form of micro-photocopies with Elisabeth Schumacher.[92] and Wilhelm Guddorf who were the intermediaries of John Sieg. It is not known if Sieg ever met Knöchel.

When Knöchel left for Germany, at least 10 communist instructors still had to be recruited and sent to Germany.[93] Arranging the travelling for the instructors became increasingly difficult, due to heavy bombing and increased German security, leaving only a river connection. The difficulty was the lines of radio communication between from the KPD in Germany, to Goulooze DIS and onwards to the Comintern in Moscow.[93] At the time, Knöchel was using two couriers, his common-law wife Cilly Hansmann, and Charlotte Garske to move intelligence between Berlin and Amsterdam for transmission to the Comintern. In the late summer 1942, the Comintern and the KPD leadership through Wilhelm Pieck began to urge Goulooze to establish a radio communication link in Berlin. Considered an extremely perilous and difficult task, Goulooze selected van Proosdy for this. [93]

Van Proosdy had to establish a legal existence in Germany by registering with the Arbeitseinsatz. Once that was completed, it was arranged for a letter to be sent by Willem Visser, an employee of a small Berlin based electricity company that was part of AEG, to offer a position of employment to Van Proosdy, as an electrician. [93] Van Proosdy left on 2 December 1942, using documentation arranged by Goulooze. In Berlin, he made contact with Knöchel, who introduced him to Kowalke who was to be trained as a radio operator.[93] Goulooze arranged for a radio transmitter to be sent by ship but it never arrived. He then forwarded a small reserve transmitter by ship as a replacement.[94]

Soviet Parachutists

In 1942, Goulooze arranged with Soviet intelligence to recruit new radio operators. These were agents that were part of Operation Pickaxe[95] and dropped by aircraft sent from RAF Tempsford. In early 1942, Goulooze arranged to receive Soviet parachutists by delegating an area close to a body of water in Veluwe, where they could be safely accommodated.[96] On 22 June 1942, Jan Wilhelm Kruyt Jr, was parachuted into the Netherlands with a wireless telegraphy set for Goulooze and false papers.[2] On 24 June 1942, Jan Wilhelm Kruyt Sr, an ardent communist and ex-clergyman was dropped by parachute from a British plane in Belgium.[97] Kruyt Sr broke his leg when he landed and was arrested shortly after by the Gestapo and sent to Fort Breendonk.[98] On 30 November, a Soviet agent Peter Kousnetzov using the alias Bruno Kühn was parachuted into the Netherlands.[2][99] Kousnetzov was found by Goulooze's men after wandering about the woods for a night.[99] Kousnetzov was originally sent to provide support the Knöchel network in Germany.[86] However, Goulooze was unable to contact Knöchel at the time, so decided to contact the Comintern executive to request that Kousnetzov work with CPN radio operator Jan De Laar instead, which was agreed. Kousnetzov joined De Laar in March 1943 and worked to train agents in the Netherlands to work inside Germany.[86]

Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle

On 18 or 19 August 1942 (sources vary), Winterink was arrested[100][101] by the Sonderkommando Rote Kapelle at a cafe in Amsterdam, after being betrayed by Konstantin Jeffremov.[101][100] Nine members of the group with two remaining radios were not discovered and continued to work. A total of 17 people from Winterink's group were arrested. This arrests led to an unpleasant aftermath for Goulooze as rumours were spread by the CPN that it was Goulooze's fault.[96] Winterink's friends even went as far in stating that Goulooze was a member of the Sicherheitsdienst.[96] Due to the rumours, distrust in Goulooze grew to an extent that it was decided by two members of the CPN, Ab Arendse and Piet Groeneveld to kill Goulooze. When their preparations were complete, they contacted Jan Postma, who decided to intervene to prevent the execution.[96]

Search for Goulooze

On 12 January 1943, Alfons Kaps was arrested by the Sonderkommando [102] in Düsseldorf, following a denunciation.[103] Under enhanced torture, he agreed to work for the Sonderkommando as a double agent or V-Mann,[lower-alpha 6] first betraying Willi Seng, who was arrested on 20 January 1943 and who was also subject to enhanced torture.[105] After the indictment, Kaps took his own life in March 1943.[102] Through Seng, Knöchel was betrayed and was arrested on 30 January 1943.[106] After he was tortured, Knöchel agreed to become a V-Mann and held a number of meetings with van Proosdy in the normal course of operation, making him effectively under the control of the Gestapo. Van Proosdy eventually realised that Knöchel was a V-Mann, due to his general demeanor and errant behaviour. He decided to make arrangements to return to Amsterdam but was arrested on 22 May 1943 before he could leave. Upon learning from a contact that van Proosdy was arrested and that the Sonderkommando was searching for him, Goulooze went into hiding.[107]

The Sonderkommando first attempted to use van Proosdy's wife in a trick to expose him, but this was unsuccessful. Even when the Gestapo managed to find a photograph of Goulooze, they were unable to locate him.[108] By 10 June 1943, Goulooze had informed all his radio and cipher people that it was likely van Proosdy was arrested and that they should go into hiding.[5] At the time, all the work and residual addresses were abandoned.[109] On the night of 1–2 July 1943, the Gestapo raided all the addresses they had been monitoring and suspected, but it yielded nothing of importance. However, on 2 July, the Gestapo arrested one of Goulooze's radio operators. [110] The man was tortured and revealed that he was to meet Goulooze's deputy, Jacobus Dankaart, the next afternoon. However the Gestapo bungled the meeting and the Dankaart was shot twice in the back when he tried to flee.[111] By the end of July several more of the radio people had been arrested and two of the radio sets had been captured by the Sonderkommando. Goulooze informed the Comintern in Moscow through the last transmitter of the situation, that the OMS group would be disbanded.[112] On the 24 August 1943, Dankaart was taken to the Zuidwal hospital in The Hague.[113] This enabled Goulooze to contact Dankaart to arrange an escape plan, which was successful on 18 September 1943.[114] During the following days, the Gestapo operation continued. Comintern agent Eugen Fried (Clément), Goulooze's collaborator and liaison with the French Communist Party was shot dead in Brussels on 17 August 1943.[115] On the 5 November 1943, Kowalke was executed. During his many months of interrogation, he never exposed any names, which saved the lives of many people in Goulooze's organisation. [116] Another close collaborator of Goulooze was Erich Gentsch who was the director of the KPD in Amsterdam since 1936. He was arrested in April 1943 and never exposed any names during his interrogation over many months.[117] He was hanged in August 1944.

Dissolution of the Comintern

On the 15 May 1943, Goulooze was listening to the radio broadcasts from Moscow, when he heard that the Comintern had been dissolved on the order of Stalin.[118] For Goulooze, who was a revolutionary, the vision that the Comintern presented was one of a need for world revolution. Harmsen posits that Goulooze must have been disappointed and even expressed some doubt about the value of the work that he had done for the organisation up to that point[119] but ultimately his revolutionary zeal wouldn't have been extinguished.[119] Goulooze wouldn't have known about the Stalinist purges that started in August 1936. He came to know about the trials of the group associated with Leon Trotsky after several Comintern officials whom he had met when he visited the Soviet Union and spoke to on the radio were replaced and this swayed his ideology to such an extent that he had a real fear of Trotskyism. He came to know about it through a copy of the memoir by the American diplomat Joseph E. Davies "Mission to Moscow", that was passed hand to hand in the Netherlands[120] that viewed the Soviet show trials under rose tinted glasses. He never came to realise the true nature of Stalinist Russia, i.e. it was merely fascism by another name. After the war, in 1946, Goulooze published "The great conspiracy; the secret war against soviet Russia" by Michael Sayers and Albert Kahn. The book falsely claims that Trotsky committed treason. Even then Goulooze had no ideological doubts and continued to fight against "fascism".[120]

After the dissolution of the Comintern, he continued to operate as much as normal as possible, even as the number of arrests increased and the membership of the party dropped from 1200 down to 400.[121] With his liaison work with the Comintern finished, Goulooze turned back to the party, which at the time had broken into disorganised groups.[122] Goulooze contacted Moscow, who advised him to reform the CPN using trusted members from before the war. Goulooze approached Jan Postma who took over the management of the CPN. Postma contacted Kees Schalker and Ko Beuzemaker and asked Goulooze to help run what remained of the party.[122] One of the first tasks for Goulooze was to arrange a liaison between the CPN and the Council of Resistance that was formed in May 1943.[123] In the following months, Goulooze continued to make contributions to the communist newspapers that were published by the CPN leadership, where they envisioned a unity of socialist and communists and a united trade union movement.[123]

Arrest

On 23 October 1943, Goulooze, Postma, Kees Schalker and Ko Beuzemaker meet in an insurance building at Catharijnesingel in Utrecht, with the expectation that the war was coming to an end, with a plan to formulate their positions after the war.[124] At a second meeting arranged in Utrecht for the 11 October led to the arrest of Ko Beuzemaker and his wife.[125] This eventually led to the arrest of Goulooze, Postma, Cornelis Schalke on the 15 November 1943.[5] They were arrested by the Sicherheitsdienst in Utrecht [1] and taken to Herzogenbusch concentration camp.[5] Dankaart had been waiting for a rendezvous with Goulooze who didn't arrive.[126] Finding he was arrested, he organised a rescue party where 6 men put on the uniform of the Ordnungspolizei. Some would act as guards and some prisoners and drive to the prison to escort Goulooze out the place. However a patrolling German guard asked them for daily password, which they didn't know and they were discovered and arrested.[127] Dankaart later managed to escape. Beuzemaker and Schalker, who were barely involved in clandestine activities were executed on 13 January 1944 on the Waalsdorpervlakte.[127]

Interrogation

.jpg.webp)

Postma was subject to enhanced interrogation but never exposed any of his collaborators. [127] Goulooze was also subject to enhanced interrogation and also refused to expose anybody nor any of the safehouses or radio locations.[128] In February 1944, he was released from detention and then taken to a seminary in Haren where further interrogation began on 21 March 1944, concerning his Belgian contacts. Twice he was taken to Brussels for identification, but due to his stamina, self-confidence and cool-headnesses he was saved from complete collapse, due to the torture.[129] At the time, the trial of the other 11 arrestees was held up due to the length of Goulooze's interrogation.[130] There was agreement reached on 11 August 1944 between the Judge and the Sicherheitsdienst that the trial should go ahead without Goulooze.[130] However, by 5 September 1944, the liberation of the Netherlands was only hours away, so Goulooze was never tried, instead he was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp along with 3000 other prisoners from Haren.[130]

Concentration camp

When Goulooze reached the concentration camp, it was the first time in months that he was able to see fellow human beings.[131] In Sachsenhausen, he discovered that some of his prior contacts held important positions. Among them were Ben Telders and Joop Zwart, who were able to obtain fake identity cards that changed Goulooze identity, effectively killing off his name.[131] This enabled him to transfer to the Heinkel aircraft works in Oranienburg where his many contacts amongst the imprisoned communists, enabled Goulooze to create an organisation to help incoming Dutch KPD and communist prisoners.[131] However, in the night of 20 April 1945, he was transferred out the camp onto a Death march in the Belower Forest.[132] After four days, units of the Red Army intersected the march and Goulooze was liberated.[132]

While Goulooze was imprisoned, Jan De Laar, van Proosdy and a radio technician from North Holland, attempted to build another radio transmitter for domestic communication but the attempt was largely a failure, as the group didn't have the capability to decode incoming coded messages.[133]

After World War II

In May 1945, the CPN leadership was reconstituted with De Groot nominally in charge. A new constitution was agreed with the title: "Renewal of Political Life in the Netherlands" and the De Waarheid newspaper, edited by De Groot, began to be published once more.[134] For a short time De Groot promoted the dissolution of the party in favour of an 'Association of Friends of Truth', because in that first post-war period after the war, the communist newspaper De Waarheid enjoyed wide popularity because of its resistance history.[135] In an editorial on 30 April 1945, De Groot stated that the CPN should be dissolved and replaced by his "Truth" association, in order to maintain the support acquired during the war and to prepare the way for a new coalition party in which the social democratic and communist parties would be joined.[135]

De Groots' found his plan wasn't as popular as he believed, as there was fierce disagreement in the party, from members from different parts of the country, who were steeped in the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism.[136] In July 1945, a conference was held. De Groot and the leadership believed that the cooperation between the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union would continue, which would eventually lead to the merging of the social democrats and the communist parties. The opposition at the conference, stated that peace wouldn't necessarily hold and that the communists should support the interests of working-class people, stating "the liquidation of the Communist Party meant the disarmament of the working class, leaving it rudderless to the leadership of the bourgeoisie".[137] When Goulooze returned to Amsterdam in mid-July 1945, he attended the conference and supported the opposition.[134] In a speech he made at the conference, he stated that political opportunism was rampant, that speaking of factions was useless as the party was dissolved and that CPN shouldn't be re-established as quickly as it was disbanded until time was taken to prepare a broad campaign to clearly understand the political necessity for re-establishing the party.[138] While it was an attack on De Groot, it wasn't personal.[139]

De Groot stood for election for political secretary on the policy of establishing his "Truth" association and was elected.[139] At the July conference, Goulooze was on the right side of the debate and certainly De Groot was fond of him,[139] but after De Groot was elected, Goulooze became an enemy of the working class.[135] However, De Groot promised to talk to Goulooze before the political control commission,[lower-alpha 7] but the conversation never took place.[140] Goulooze made several attempts to convince De Groot to hold that conversation, in essence to confirm a place in the new party hierarchy for Goulooze, but the discussion with the political control commission mever took place. From that point forward, Goulooze was no longer a political force in the CPN.[140]

Publishing house

As Goulooze no longer took an active part of the CPN (although still a member of the party), he began to looking for a new role for himself, where he could contribute to the political life of the Netherlands.[140] On 16 May 1945, Goulooze opened The Republic of Letters, a left-wing publishing house.[140] Huub de Groot and Mels de Jong managed the business.[140] The company published both political books for example, by Theun de Vries, Eduard Veterman, Klaas van der Geest and Adrianus Michiel de Jong.[141] Children's books became particularly popular. Goulooze also published American and Russian authors, for example, Howard Fast, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Sholokhov and Ilya Ehrenburg.[141]

Smears and slander

In mid-1947, Jan Schalker, the son of Kees Schalker and a member of the secretariat of the CPN, informed Goulooze that he was dismissed as director of the Pegasus publishing house.[142] Ostensibly, this was ensure the correct running of the business, although in fact it was latest step of a smear campaign that had begun after the conference. In essence, the smears were designed to isolate and harm Goulooze as a publisher.[142] On 8 July 1947, Goulooze wrote a letter to the CPN executive demanding that he be brought before the political control commission, promising to account for his "illegal" work.[142] However, this didn't happen and the smear campaign continued in the following months.[142] In 1948, a much more aggressive smear in form of slander during a press campaign that was launched against him in theDe Waarheid. In the artivle the CPN made a number of insinuations against Goulooze about his role in the war.[142] After the press campaign, the CPN received word that its political enemies were planning to attack Goulooze. The CPN decided to distance itself from Goulooze. On the 17 June 1948, Harry Verhey, director of the CPN sent Goulooze a letter telling him that he was temporarily suspended as a member of the CPN, pending an investigation. The investigation which never took place.[143] Although Goulooze protested, the suspension was never lifted.[143] The CPN weren't the only people who attacked him. The PvdA issued a brochure "De Ysberg, Communistische spionnage! (Amsterdam z.j.)" that was full of half-truths and misinformation that caused Goulooze considerable discomfort and despair on its publication. [144] The attacks against him continued throughout the late 1940s into the 1950s.[144] He continued to follow the political developments in the world. By the late 1940s, his health began to fail him.

Death

On 10 June 1949, his wife Nell died of cancer and in 1951 Goulooze suffered a heart attack.[141] On 10 September 1965, Goulooze suffered a fatal heart attack that ended his life.[145]

Literature

- Harmsen, Ger (1967). Daan Goulooze. Uit het leven van een communist. Amboboeken (in Dutch). Utrecht: Ambo. OCLC 12739298.

- Voerman, Gerrit, historicus (2001). De meridiaan van Moskou : de CPN en de Communistische Internationale, 1919-1930 (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Veen. ISBN 9789020456387. OCLC 1169809112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stutje, Jan Willem (2000). De man die de weg wees : leven en werk van Paul de Groot 1899-1986 (in Dutch). Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij. ISBN 9789023439080.

- Engelen, D. (1998). Geschiedenis van de Binnenlandse Veiligheidsdienst (in Dutch). Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers. ISBN 9789012086479. OCLC 48671178.

- Pelt, Wilhelmus Franciscus Stanislaus (1990). Vrede door revolutie : de CPN tijdens het Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939-1941) (in Dutch). 's-Gravenhage: SDU. ISBN 9789012065016. OCLC 1024184540.

- Harmsen, Ger (1986). "Voor de derde maal Daan Goulooze. Nabeschouwing, aanvullingen en correcties". Bulletin Nederlandse Arbeidersbeweging (in Dutch). Nijmegen. 8: 25–40.

- Mellink, A.F. (December 1987). "Voorspel en verloop van de juli-conferentie 1945". Bulletin Nederlandse Arbeidersbeweging (in Dutch). Nijmegen. 15: 28–33.

- Constandse, A.L. "De Gids. Jaargang 130 The life of a communist". De Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch). Taalunie, de Vlaamse Erfgoedbibliotheken en de Koninklijke Bibliotheek (KB), nationale bibliotheek van Nederland. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- Davies, Joseph E. (1941). Mission to Moscow (in Russian). New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Herlemann, Beatrix (1982). Die Emigration als Kampfposten : die Anleitung des kommunistischen Widerstandes in Deutschland aus Frankreich, Belgien und den Niederlanden. Mannheimer sozialwissenschaftliche Studien (in German). Vol. 18. Königstein im Taunus: Hain Verlag. ISBN 3-445-02252-6.

- Herlemann, Beatrix (1986). Auf verlorenem Posten : kommunistischer Widerstand im Zweiten Weltkrieg : die Knöchel-Organisation. Reihe Politik- und Gesellschaftsgeschichte (in German). Vol. 15. Bonn: Verlag Neue Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-87831-434-5.

- Sayers, Michael; Kahn, Albert Eugene (1946). The great conspiracy; the secret war against soviet Russia. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Notes

- A full description of the cypher used is contained on pp260-263 in Harmsen.

- The encryption used was 5-figure based substitution cypher, with a subtractor and key phrase.

- A new cypher code that was kept in reserve, for emergency use.

- The Volksdagblad was renamed in May 1940.

- Wilhelm Knöchel is identified as Alfred Knöchel in Kesaris page 71, section IV. "Alfred" was Knöchel's alias.

- Known in Germany as V-Mann, short for Vertrauens-mann.[104] (German:V-Mann, plural V-Leute), they were arrested prisoners, who were committed to spying activity for the Gestapo, who promised severe punishment such as the death penalty, if they refused.

- To create a position for Goulooze in the CPN

References

- Kesaris 1979, p. 281.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 70.

- Bayerlein & Albert 2013, pp. 11–13.

- Foray 2012, p. 62.

- Goulooze & BWSA 1988.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 282.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 152.

- De Groot 1965, p. 44.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 23.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 26.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 30–33.

- Postma & BWSA 1988.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 30–34.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 50.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 51.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 53.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 55.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 56.

- Voermann 2001, p. 398.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 58.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 61.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 63.

- Voermann 2001, p. 370.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 69.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 71–72.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 73.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 75–76.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 78.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 79–80.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 80.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 81–82.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 83.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 84.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 85.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 85–89.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 87.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 89.

- Altena 1992, p. 479.

- Altena 1992, p. 478.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 91.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 93.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 95.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 96.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 98.

- Weber & HerbstWenzel 2008.

- Lazić 1986, p. xxviii.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 103.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 106.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 114.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 115.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 120.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 123.

- O'Sullivan 2010, p. 259.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 125.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 124.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 57.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 69.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 383.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 127.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 66.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 58.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 132–133.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 133.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 135.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 137.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 140.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 141.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 142.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 138.

- Foray 2012, p. 66.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 143.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 145.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 146.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 147.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 149.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 151.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 153.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 154.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 156.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 157.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 172.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 173.

- Nelson 2009, p. 270.

- Gebauer 2011, pp. 496–501.

- Weber, Herbst & Knöchel 2008.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 71.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 173–74.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 174–75.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 178.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 179.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 181.

- Nelson 2009, p. 71.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 182.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 183.

- Tyas 2017, p. 106.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 169.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 170.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 303.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 171.

- Kesaris 1979, p. 389.

- Stadsarchief Amsterdam & Inventory of the archives of Riek Milikowski-de Raat.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 185.

- Gebauer 2011, p. 237.

- Hogg 2016, p. 48.

- Weber & Herbst 2008.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 186.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 187.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 187–188.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 187–189.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 190.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 191.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 192.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 195.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 196.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 197.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 198.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 199.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 201.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 203.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 204.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 205.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 211.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 212.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 214.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 216.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 217.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 218.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 222.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 223.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 224.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 225.

- Harmsen 1980, p. 226.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 227–228.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 231.

- Harmsen 2003.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 232.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 233.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 234.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 235.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 236.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 237.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 238.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 239.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 241.

- Harmsen 1980, pp. 253.

Bibliography

- Altena, Bert (1992). Die Rezeption der Marxschen Theorie in den Niederlanden (in German). Karl-Marx-Haus. ISBN 978-3-926132-18-5.

- "30480 Inventory of the archives of Riek Milikowski-de Raat". Het Stadsarchief Amsterdam (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Bayerlein, Bernhard H; Albert, Gleb J, eds. (2013). "SECTION II. NEWS ON ARCHIVES, HOLDINGS AND INSTITUTIONS". The International Newsletter of Communist Studies. Bochum: Ruhr University Bochum. XIX (26). Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Foray, Jennifer L. (2012). Visions of Empire in the Nazi-Occupied Netherlands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01580-7.

- Gebauer, Thomas (2011). Das KPD-Dezernat der Gestapo Düsseldorf. disserta Verlag. ISBN 978-3-942109-74-1.

- Harmsen, Ger (1988). "GOULOOZE, Daniel | BWSA". International Institute of Social History (in Dutch). Biografisch Woordenboek van het Socialisme en de Arbeidersbeweging in Nederland. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- Harmsen, Ger (1988). "POSTMA, Jan | BWSA". International Institute of Social History (in Dutch). Biografisch Woordenboek van het Socialisme en de Arbeidersbeweging in Nederland. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- Harmsen, Ger (10 February 2003). "GROOT, Saul de". BWSA (in Dutch). Biografisch Woordenboek van het Socialisme en de Arbeidersbeweging in Nederlan. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- De Groot, Paul (1965). De dertiger jaren 1930-1935: Herinneringen en overdenkingen. Pegasus.

- Harmsen, Ger (1980). Rondom Daan Goulooze : uit het leven van kommunisten. Sunschrift, 152. (in Dutch) (2 ed.). Nijmegen: SUN. ISBN 9789061681526. OCLC 71392888.

- Hogg, Ian V. (12 April 2016). German Secret Weapons of World War II: The Missiles, Rockets, Weapons, and New Technology of the Third Reich. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-5107-0368-1.

- Kesaris, Paul. L, ed. (1979). The Rote Kapelle: the CIA's history of Soviet intelligence and espionage networks in Western Europe, 1936–1945 (pdf). Washington DC: University Publications of America. ISBN 978-0-89093-203-2.

- Lazić, Branko M. (1986). Biographical dictionary of the Comintern. Hoover Press publication, 340 (New, revised, and expanded ed.). Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 9780817984014.

- Nelson, Anne (2009). Red Orchestra. The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6000-9.

- O'Sullivan, Donal (2010). Dealing with the Devil: Anglo-Soviet Intelligence Cooperation in the Second World War. Peter Lang. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-4331-0581-4.

- Voermann, Gerrit (2001). De meridiaanvan Moskou De Communistische Internationale, 1919-1930 (PDF) (Thesis.). L.J. Veen Amsterdam/Antwerpen. ISBN 9020456385. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Weber, Hermann; Herbst, Andreas (May 2008). "Seng, Willi * 11.2.1909, † 24.5.1944". Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten. Karl Dietz Verlag., Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Weber, Hermann; Herbst, Andreas. "Knöchel, Wilhelm * 8.11.1899, † 12.6.1944". Handbuch der Deutschen Kommunisten. Karl Dietz Verlag, Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Weber, Hermann; Herbst, Andreas. "Wenzel, Johann". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur (in German). Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Tyas, Stephen (25 June 2017). SS-Major Horst Kopkow: From the Gestapo to British Intelligence. Fonthill Media. p. 106.

.jpg.webp)

%252C_Bestanddeelnr_920-1109.jpg.webp)