Darrington, Washington

Darrington is a town in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located in a North Cascades mountain valley formed by the Sauk and North Fork Stillaguamish rivers. Darrington is connected to nearby areas by State Route 530, which runs along the two rivers towards the city of Arlington, located 30 miles (48 km) to the west, and Rockport. It had a population of 1,347 at the 2010 census.

Darrington, Washington | |

|---|---|

Distant view of Darrington from the northwest | |

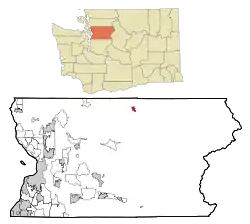

Location of Darrington, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 48°15′8″N 121°36′14″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Snohomish |

| Founded | 1891 |

| Incorporated | October 15, 1945 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Dan Rankin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.75 sq mi (4.54 km2) |

| • Land | 1.73 sq mi (4.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 554 ft (169 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,347 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 1,421 |

| • Density | 822.34/sq mi (317.59/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98241 |

| Area code | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-16690 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1518492[4] |

| Website | townofdarrington |

Non-indigenous settlement in the area began in 1891 at the site of a Skagit campsite between the two rivers, near the traditional home of the Sauk-Suiattle tribe. Prospectors had arrived in the area during the 1880s while looking for gold and other minerals, but were quickly displaced by the logging industry that would come to dominate Darrington for much of the 20th century. The Northern Pacific Railway built a branch line to the town in 1901 and ushered in several years of growth.

During the Great Depression, Darrington hosted a Civilian Conservation Corps camp that improved roads, trails, and firefighting infrastructure in the nearby Mount Baker National Forest. Several waves of Appalachian emigrants arrived in the area from North Carolina, forming a culture that is seen in the town's annual bluegrass festival and rodeo.

Darrington was incorporated as a town in 1945, under a mayor–council government. Its economy has transitioned away from logging and towards tourism, particularly outdoor activities such as hiking, mountain climbing, and fishing, due to its proximity to the Mount Baker–Snoqualmie National Forest. The Darrington area is 554 feet (169 m) above sea level and receives significantly more precipitation and snowfall than the Puget Sound lowlands.

History

Prehistory and early exploration

The upper Stillaguamish and Sauk valleys on the Sauk, Suiattle, and White Chuck rivers were historically inhabited by various Native American Coast Salish groups, including the Stillaguamish, the Sauk-Suiattle, and the Upper Skagit.[5] The Sauk-Suiattle maintained a village site and burial ground near modern-day Darrington, while the Skagit used the plain between the Stillaguamish and Sauk rivers as a portage for overland transport of canoes. The portage, Anglicized as Kudsl Kudsl or Kuds-al-kaid, was also used as a transiting point for travelers from Eastern Washington on their way to and from the Puget Sound coast.[6][7]

The area was known as Burn or Sauk Portage to early surveyors and visitors from towns along the Puget Sound coastline. A group of railroad surveyors for the Northern Pacific Railway arrived in modern-day Darrington in 1870 while plotting the potential route for a railroad crossing the Cascades to Lake Chelan, but ultimately chose Stampede Pass to the south.[8] The North Stillaguamish Valley was nicknamed "Starve Out" by early settlers, who arrived alone and underprepared for the area's conditions, leading to several difficult winters.[9] Soldiers sent to the area by the valley settlers threatened to evict the Sauk-Suiattles; this did not occur as the settlers' claim that the Sauk-Suiattle were hostile and had attacked them was determined to be unfounded. The tribe later hired surveyors to record their claims to the eastern side of the Sauk River, lands that currently comprise their Indian reservation.[10]

The discovery of gold and other valuable minerals in the Monte Cristo area in 1889 lured prospectors into the North Cascades and stimulated the development of the surrounding valleys. A 45-mile (72 km) wagon road along the Sauk River connecting Monte Cristo to Sauk Prairie and the settlement of Sauk City on the Skagit River was built in 1891, later forming part of the modern Mountain Loop Highway.[11][12] It was only used for three years before being replaced by the Everett and Monte Cristo Railway to the south; until that time, the Sauk Prairie at the modern site of Darrington was an overnight camping spot for prospectors.[11] Nearby areas were explored by prospectors who made over a hundred claims to tracts of land in the highlands around the valley, including Gold Hill.[13][14]

Establishment and early development

.jpeg.webp)

The Sauk Prairie campsite evolved into a settlement that was known as "The Portage" and developed around several homesteads established between 1888 and 1891.[15] A vote on a name was held by several pioneer residents in July 1891 in advance of the establishment of a post office.[16] The vote was tied between two options, Portage (in some accounts, Norma) and Darrington, the maiden name of settler W. W. Cristopher's mother.[16][17] According to some reports, the name was originally to be "Barrington" but was changed due to a mistake from the Postal Department or by the townspeople to resemble the word "dare".[18][19] By the end of the decade, the town had gained a schoolhouse, a general store, a hotel, and a postmaster, Fred Olds, whose horse inspired the naming of Whitehorse Mountain.[5][20]

Darrington's residents lobbied the Seattle and International Railway for the construction of a branch line from Arlington to the town as early as 1895,[21] offering a 15-year contract to ship 75 percent of the area's extracted ores. The railroad agreed to the offer and began construction in 1900. It later merged with the Northern Pacific Railway, outpacing Great Northern and their plans to build a railroad to their timber holdings in the Sauk River valley.[22] Railway crews arrived in the Darrington area by the following year and the first train arrived at the town's depot in 1901.[23]

Several sawmills and other timber industries began in the years following the railroad's completion, as mining fortunes in the surrounding area dwindled.[23] Most of the original prospectors had left the Darrington area during the Klondike gold rush of the late 1890s, while those who remained established a single smelter in the mountains.[24] A Bornite mine was later developed at Long Mountain in hopes of reviving mining in the area, but was abandoned after its mineral deposits were found to be smaller than expected.[9][25] By 1906, Darrington had more than a hundred residents; a second hotel and the town's first social club had been built.[5][14] The U.S. Lumber Company, which began in 1901 as the Allen Mill, was the largest employer in Darrington during the early 1910s, producing 23,000 board feet (54.28 m3) of wood per day.[26]

U.S. Lumber angered the townspeople by hiring 21 Japanese laborers at similar wages to their white counterparts. In June 1910, a mob of white men rioted and drove the Japanese out of town after little resistance, paying for their train fare to Everett after allowing them to retrieve their belongings.[27] A report by Seattle-based vice-consul Kinjiro Hayashi was forwarded to the Japanese ambassador and state government.[28] The company filed for an injunction after rioters had threatened to burn its Darrington mill and other properties should it attempt to return the Japanese laborers.[29] The injunction was denied,[30] but the townspeople relented and allowed 20 Japanese laborers to return to the mill a week later following Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu's visit to Seattle.[5][26][31]

Early 20th century

.jpg.webp)

Darrington's residents resisted the county government's dry plan to prohibit the sale of alcohol and close the town's saloons. They circulated a petition to incorporate Darrington as a fourth-class city in order to continue alcohol sales, but the attempt was thwarted after protests by U.S. Lumber and several civic leaders.[26][32] On July 5, 1910, the town voted 46–35 in favor of remaining a "wet" settlement, but the countywide plebiscite the same day passed in favor of prohibition.[26]

The town grew substantially in the early 1920s, with new sawmills attracting more residents and businesses. The wagon road along the North Fork Stillaguamish River (now part of State Route 530) was improved. A local improvement club established a fire department, a municipal water supply, and electrical service. Standard Oil built an auxiliary gas station in 1922 to serve the area, and a stagecoach service started at the same time.[33] Darrington gained its first movie theater in 1923, a high school in 1925, and a purpose-built jail that replaced a disused boxcar.[5][34]

Falling lumber prices during the Great Depression led several small sawmills in the Darrington area to suspend operations for a full year and laying off most of the town's workforce in late 1930.[35] The town suffered outbreaks of scarlet fever and smallpox in 1931, followed by winter storms that damaged bridges and roads in the Sauk valley.[36] The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work program established Camp Darrington on May 20, 1933, to provide employment for up to 200 men from northern Snohomish County.[5] The townspeople established a local cooperative association in 1935 to create jobs, including 33 at an independent sawmill, and provide services at a shared cost.[37]

Camp Darrington was primarily used to fight wildfires and develop infrastructure in the Darrington district of the Mount Baker National Forest, including roads, trails, and a series of fire lookout towers atop nearby mountains.[38][39] Among its projects was the Mountain Loop Highway, which provided connections between ranger stations in Darrington and Granite Falls and also opened up the Cascades backcountry to logging and recreation.[40] The camp employed the first wave of Appalachian emigrants from North Carolina, who would eventually form a majority of the town's population.[41][42] Camp Darrington workers also assisted in the creation of two winter sports areas that were equipped with ski runs, toboggan trails, and a ski jump.[43] The Works Progress Administration, another federal jobs program, provided funds to replace the town's overcrowded high school in 1936.[44]

Incorporation and decline of lumber

Darrington reached a population of 600 residents in 1945 and was officially incorporated as a fourth-class town on October 15, 1945, following a 96–60 vote in favor.[32] The townspeople celebrated by establishing an annual summer festival, the Timberbowl, which ran until 1967 and was initially used to raise funds for a fire engine and other equipment.[45] A two-story town hall was built in 1947, housing the town council chambers, offices for town officials, the police department, the fire department, and a public library.[45][46] In 1952, the town built a dedicated community center to serve as a venue for various social functions and a general gymnasium with seating for 1,200 people.[47] A new high school and municipal airport opened in 1958 at opposite ends of the town.[48][49]

Railroad companies with large timber holdings in the area began to leave in the 1960s, leading to the rise of independent "gyppo" loggers who salvaged discarded timber while under contract to regional paper mills.[50] A large open-pit mine on Miners Ridge planned by Kennecott in the late 1960s was halted after intervention from environmental activists and local politicians.[51] Northern Pacific ended passenger rail service to the Darrington area in the 1960s, and the passenger depot was demolished in 1967.[22] The railroad was eventually abandoned in 1990 and its right-of-way was acquired by the county for conversion into a rail trail.[52][53]

The gyppo operations gave way to a small local timber company, Summit Timber, which acquired the largest sawmill in Darrington, now the Hampton mill.[54][55] Several smaller mills in Darrington and surrounding communities, including four for cedar shakes, closed during the 1960s, leading to further population decline.[56] The area's timber industry was also adversely affected by tighter logging restrictions on federal lands during the 1980s and 1990s meant to protect the mountain habitats of threatened and endangered species, including the northern spotted owl.[57] In response, Summit transitioned to processing private forests and lands managed by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, maintaining its position as the town's largest employer.[58][52] The loss of timber-industry jobs led to local protests, part of the "timber wars" that erupted across logging communities in the Pacific Northwest during the 1990s.[59][60]

Tourism economy and modern Darrington

The town government sought to diversify Darrington's economy and focus on tourism as an alternate industry, creating new festivals and promoting its existing bluegrass festival and rodeo.[61][62] It adopted strong land use controls to preserve its rural character in the 1970s, which prevented new development until 2002.[63] Darrington subsequently developed into a bedroom community for commuters working in Everett and Marysville.[64] Opposition from residents forced the town government to drop plans for a 400-bed minimum-security prison work camp in 1990.[56]

The town government unsuccessfully campaigned for a NASCAR racetrack and regional swimming center in the early 2000s, aiming to become an all-year destination for the county.[65][66] Several major floods in the late 1990s and early 2000s damaged properties along the rivers; in 2003, a flood washed out part of the Mountain Loop Highway.[67] The highway was not restored until 2008, costing Darrington approximately $750,000 in tourist revenue and forcing several businesses to close.[68][69] Darrington's main lumber mill laid off 67 workers in 2011, citing the effects of the Great Recession and declining demand.[70] The town government, running on a small budget of $1.6 million, accepted several grants from the state to upgrade its water system and repair streets during the recession.[71]

On March 22, 2014, a major mudslide on a hillside near Oso, 12 miles (19 km) west of Darrington, destroyed dozens of homes and a section of State Route 530, cutting off direct road access between Arlington and Darrington for two months.[72] It killed 43 people, becoming the deadliest landslide in U.S. history and the deadliest natural disaster in state history since the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.[73][74] Darrington was one of the main staging areas for disaster response workers and supplies; the community center was used as an emergency shelter for victims and the rodeo grounds became an animal shelter and housing for workers.[75][76][77]

State Route 530 was partially reopened by early June and a permanent replacement was opened in September.[78][79] The increased costs to local businesses resulting from the long detour via State Route 20 were mitigated with low-interest loans from the Small Business Administration and recovery funds, including $9.5 million in private donations.[80][81] The tourism industry in Darrington also received a state-funded advertising campaign, keeping revenue and visitation for local events at pre-slide levels.[82][83][84] The state government, together with the Economic Alliance Snohomish County and Washington State University, drafted a $65 million economic recovery plan that was put into effect in 2016.[85]

Geography

Darrington is located in the northeastern reach of Snohomish County in Western Washington, just south of the Skagit County border. It is 28 miles (45 km) east of Arlington, the nearest city, and 74 miles (119 km) northeast of Seattle.[86] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.67 square miles (4.33 km2), of which, 1.65 square miles (4.27 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.05 km2) is water.[87]

Darrington is situated on a plain between the North Fork Stillaguamish River to the west and the Sauk River to the east.[5] The plain is 5 miles (8.0 km) long and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) wide,[23] at approximately 554 feet (169 m) above sea level in a valley between foothills of the Cascade Mountains, including the 6,852-foot (2,088 m) Whitehorse Mountain.[88][89]

The plain was formed by lahar deposits from several eruptions of Glacier Peak, 25 miles (40 km) to the southeast.[90] The area remains in the volcano's lahar hazard zone and also lies on a fault line that last produced a major earthquake less than 500 years ago.[90][91] Soil in The Darrington area is primarily composed of glacial sands and gravels that have deposits of various mineral ores, including gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, antimony, arsenic, mercury, and iron.[92]

Climate

Darrington has a general climate similar to most of the Puget Sound lowlands and the Cascades foothills, with dry summers and mild, rainy winters moderated by a marine influence from the Pacific Ocean.[93] Temperatures in Darrington typically differ by approximately 10 °F (5.6 °C) from Everett and other coastal cities in the county, with colder winters and warmer summers.[88] The majority of the region's precipitation arrives during the winter and early spring, and Darrington averages 152 days of precipitation annually that totals 79.35 inches (201.5 cm) on average—significantly higher than areas in lowland Snohomish County.[18][94] Darrington also receives significantly more snowfall than other cities in the county due to being in the mountains, with 10 to 15 days on average and approximately 39 inches (99 cm) of snowfall annually since 1911.[88][94]

July is Darrington's warmest month, with average high temperatures of 77.5 °F (25.3 °C), and January is the coolest, at an average high of 40.8 °F (4.9 °C).[94] The highest recorded temperature, 107 °F (42 °C), occurred in July 2007, and the lowest, −14 °F (−26 °C), in January 1950.[94] According to the Köppen climate classification system, Darrington has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb).[95]

| Climate data for Darrington, Washington | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

70 (21) |

82 (28) |

91 (33) |

103 (39) |

105 (41) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

94 (34) |

77 (25) |

65 (18) |

107 (42) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40.8 (4.9) |

45.9 (7.7) |

52.1 (11.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

66.3 (19.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.4 (25.2) |

71.1 (21.7) |

60.3 (15.7) |

47.8 (8.8) |

41.6 (5.3) |

59.2 (15.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27.7 (−2.4) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

32.8 (0.4) |

36.5 (2.5) |

42.4 (5.8) |

47.5 (8.6) |

50.0 (10.0) |

50.3 (10.2) |

45.2 (7.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

33.3 (0.7) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −14 (−26) |

−11 (−24) |

0 (−18) |

20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

30 (−1) |

24 (−4) |

24 (−4) |

16 (−9) |

−4 (−20) |

−10 (−23) |

−14 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 11.84 (301) |

8.73 (222) |

8.44 (214) |

5.16 (131) |

3.60 (91) |

2.83 (72) |

1.43 (36) |

1.63 (41) |

3.62 (92) |

7.39 (188) |

11.84 (301) |

12.85 (326) |

79.35 (2,015) |

| Average precipitation days | 17 | 14 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 151 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[94] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Darrington's largest industry remains logging, centered around several small companies and the Hampton sawmill, the town's largest employer at 160 jobs.[96][97] Hampton acquired the disused sawmill from Summit Timber in 2002 and reopened it the following year after $15 million in renovations.[98] The sawmill primarily processes western hemlock and Douglas fir from nearby state and local lands.[99][100] Other major industries in the town include tourism and outdoor recreation, educational services for the Darrington School District, and forestry management.[86][88] The town has a grocery store, a bakery, several restaurants, a bookstore, and a microbrewery.[101][102] The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe has a small casino and bingo hall that employs 50 people.[103]

A 2015 Census survey estimated that Darrington had a workforce population of 1,138 and an unemployment rate of 9.3 percent.[104] The most common employers for Darrington residents are in manufacturing (23.8 percent), followed by educational and health services (17.6 percent), retail (13.7 percent), and public administration (10.5 percent).[104] Approximately 9.9 percent of Darrington residents also work within the town, while 13 percent commute to Everett, 6.4 percent work in Seattle, and 5.7 percent work in Arlington.[105] The average one-way commute for the town's workers is approximately 36.5 minutes; 85.3 percent of commuters drove alone to their workplace, while 6.8 percent carpooled and 6.2 percent walked or used other modes of transport.[104]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 921 | — | |

| 1960 | 1,272 | 38.1% | |

| 1970 | 1,094 | −14.0% | |

| 1980 | 1,064 | −2.7% | |

| 1990 | 1,042 | −2.1% | |

| 2000 | 1,136 | 9.0% | |

| 2010 | 1,347 | 18.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,421 | [3] | 5.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[106] | |||

Darrington is the third-smallest incorporated place in Snohomish County, ahead of Woodway and Index, with an estimated population of 1,421 in 2019.[107][108] Historically, the Darrington area's population peaked at an estimated 3,500 to 4,000 in the early 20th century during the heyday of logging in the area, which also attracted Scandinavian and Western European immigrants.[5][109] The town saw an influx of Appalachian transplants from North Carolina (particularly the area around Sylva) in the 1940s and 1950s,[110] whose families remain in the Darrington area, influencing traditions and local culture.[18][111] The town's population has remained relatively stable since the 1960s, declining by 230 residents by 1990 and rebounding since then.[18][56][108] Darrington predominantly has single-family residences, with only 36 multi-family units reported in 2010.[112]

According to 2012 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, Darrington has a median family income of $60,750, and a per capita income of $18,047, ranking 227th of 281 areas within the state of Washington.[104][113] Approximately 16.7 percent of families and 20.9 percent of the overall population were below the poverty line, including 24 percent of those under the age of 18 and 8.9 percent aged 65 or older.[104] Darrington is described as economically depressed and has median household incomes that are far below the Snohomish County average.[114]

2010 census

As of the 2010 U.S. census, there were 1,347 people, 567 households, and 349 families residing in the town. The population density was 816.4 inhabitants per square mile (315.2/km2). There were 644 housing units at an average density of 390.3 per square mile (150.7/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 92.4 percent White, 2.4 percent Native American, 0.4 percent Asian, 0.5 percent from other races, and 4.2 percent from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 3.2 percent of the population.[2]

There were 567 households, of which 30.9 percent had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.8 percent were married couples living together, 9.5 percent had a female householder with no husband present, 7.2 percent had a male householder with no wife present, and 38.4 percent were non-families. Individuals made up 32.6 percent of all households; and 13.1 percent had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 2.96.[2]

The median age in the town was 41.4 years. Residents under the age of 18 accounted for 22.7 percent of the population, 7.7 percent were between the ages of 18 and 24, 24.9 percent were from 25 to 44, 28.1 percent were from 45 to 64 and 16.6 percent were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 50.9 percent male and 49.1 percent female.[2]

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 1,136 people, 473 households, and 292 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,171.9 people per square mile (452.2/km2). There were 505 housing units at an average density of 520.9 per square mile (201/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 94.98 percent White, 1.67 percent Native American, 0.35 percent Asian, 0.26 percent from other races, and 2.73 percent from two or more races. Hispanic of Latino residents of any race were 1.23 percent of the population.[115]

There were 473 households, out of which 30.9 percent had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49 percent were married couples living together, 8.7 percent had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.1 percent were non-families. 31.7 percent of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.6 percent had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.08.[115]

In the town, the age distribution of the population shows 27.1 percent under the age of 18, 6.9 percent from 18 to 24, 27.5 percent from 25 to 44, 21.9 percent from 45 to 64, and 16.6 percent who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.6 males.[115]

The median income for a household in the town was $32,813, and the median income for a family was $44,063. Males had a median income of $36,429 versus $25,625 for females. The per capita income for the town was $17,384. About 4.7 percent of families and 8.9 percent of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.9 percent of those under age 18 and 6.6 percent of those age 65 or over.[115]

Government and politics

Darrington is an incorporated town that operates under a mayor–council form of government.[116] It is one of two towns within Snohomish County, the other being Index, the only incorporated place in the county with a smaller population than Darrington.[117] The five town council members regularly meet twice per month and are elected to four-year terms alongside the mayor.[118] The current mayor, Dan Rankin, a sawmill owner and former councilmember, was elected in 2011; he has twice been re-elected.[119]

The town government handles and manages public safety, public works, administration, and parks and recreation.[116] It also operates a public cemetery,[120] the municipal airport, and contracts for utility services.[121] The mayor and town council appoint a clerk treasurer and the heads of various government departments.[116]

As of 2016, the town government employs seven people and has an annual budget of $3 million.[116] The town has an independent fire department with two stations, but contracts with the Snohomish County Sheriff for policing and emergency services.[122][123] The town also has a public library branch operated by the Sno-Isle Libraries system and located in the town hall complex, which was built in 1990 and expanded in 2008.[124][125] The town lacks home delivery of mail, requiring residents to use the local post office.[126]

While Snohomish County as a whole favors the Democratic Party in elections, Darrington has generally supported Republican candidates. It is represented at the county and state levels by officials from that party. Nate Nehring has been county councilman for the 1st district, which includes Darrington, since his appointment in 2017.[127] The town is within the state's 39th legislative district.[128] At the federal level, Darrington is part of Washington's 1st congressional district,[128] which has been represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by Democrat Suzan DelBene since 2012.[129]

During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Darrington had the highest percentage of votes in Snohomish County for Republican Donald Trump, at 61 percent compared to 33 percent for Democrat Hillary Clinton, who carried the county. Similarly, in the same year's gubernatorial election, 59 percent of Darrington voters preferred Republican Bill Bryant over incumbent Democrat Jay Inslee, who was re-elected.[130] Some Democrats have succeeded in Darrington, however. In the 2012 presidential election, Barack Obama won the town with 52 percent of the vote.[130]

Culture

Darrington describes itself as a self-sufficient and tight-knit community, owing to its isolation and small population.[131][132] Descendants of emigrants from North Carolina, particularly the Sylva area, after World War II, shaped many of the traditions and customs in the Darrington area.[110] The term "going down below" is sometimes used among Darrington residents to refer to trips outside of the town.[133] Memorial dinners and fundraisers during funerals are hosted by its residents, typically attended by up to a fourth of the town's population.[134][135] Darrington also has a strong tradition of volunteerism, which it sometimes relies on in lieu of municipal services.[89][136]

Events and festivals

Darrington has a community events complex and park located 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the town, which is home to several annual events, including a rodeo and a Bluegrass festival.[137] The Darrington Timberbowl Rodeo began in 1964 and typically draws over a thousand spectators during its two-day run in late June.[138] The rodeo was cancelled in 2013 after an inspection found the venue's bleachers to be unsafe, but $25,000 in repairs funded by state grants allowed it to resume the following year.[139] The Timberbowl Rodeo is named for a former festival that was held annually in late June from 1946 to 1967, and featured various logging events and competitions in addition to a town parade.[45][140][141]

The Darrington Bluegrass Festival is held for three days every July and was started in 1977 by descendants of Appalachian transplants to the area.[142] The festival draws around 10,000 people, including visitors who use an adjacent campground and participate in communal jam sessions. Prominent Bluegrass groups, including Bill Monroe, the Gibson Brothers, and Rural Delivery, have performed at Darrington's Whitehorse Mountain Amphitheater.[139][143] From 2006 to 2019, the amphitheater also hosted the Summer Meltdown jam festival in early August, which attracted a wide variety of musical acts.[144] The four-day event typically drew 4,000 visitors and 40 acts, as well as art pieces that were installed around the campgrounds.[145] Both festivals were cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[146]

The town also has several other annual events, including Darrington Day in late May, a Fourth of July parade, and a street fair in July.[147][148] Darrington formerly hosted an annual wildflower festival and an annual Christian music festival in the 1990s during the transition to a tourism-based economy.[62][111]

Media

With no local newspaper, events in Darrington are covered by Everett's daily newspaper, the Herald, a daily publication from Everett, and the weekly Arlington Times. The town's first newspaper, named The Wrangler, was published from 1907 to 1915 by the Darrington Literary Society. A second newspaper, The Darrington News, was published for two years from 1947 to 1949 and was followed by the Timber Bowl Tribune, which was printed in Darrington and Concrete using a plant owned by The Concrete Herald. The Tribune was active from 1955 to 1958, when it was folded into the Arlington Times.[149][150]

Parks and recreation

Darrington is surrounded by the Mount Baker–Snoqualmie National Forest and serves as the headquarters of the Darrington Ranger District, a unit of the U.S. Forest Service.[151] The area includes three designated wilderness areas, Glacier Peak, Henry M. Jackson, and Boulder River, and over 300 miles (480 km) of hiking and backcountry trails that are also open to mountain biking and horseback riding.[152] Darrington has several campgrounds, roadside recreational areas, fishing areas, and whitewater rafting courses along the Sauk and Suiattle rivers.[152][153] The Mountain Loop Highway connects Darrington to various scenic areas, including birdwatching hotspots and the Pacific Crest Trail system.[154]

The town government also maintains several small parks in Darrington, totaling 24 acres (9.7 ha) of open space.[155] Old School Park sits within view of Whitehorse Mountain and has a gazebo, a playground, a skate park, and a pump track for bicycles.[156] Harold Engles Park has a disc golf course and a lawn, and Nels Bruseth Memorial Garden has historic exhibits and a rhododendron garden.[157] The Snohomish County government owns and operates Whitehorse Community Park, which includes several baseball and softball fields on 80 acres (32 ha) north of the town that opened in 2007.[158][159] Darrington is the only town in the state to have a permanent archery range, which is one of three that regularly hosts events organized by the National Field Archery Association.[153] The archery complex includes six full ranges, trails, concession stands, and 190 acres (77 ha) of reserved space.[160] The town also has a community center that was built in 1954 and typically functions as a gymnasium and gathering space.[136]

Historic preservation

The town has a small historical society that preserves photographs and other documents for research.[161] The Darrington Ranger District has four structures listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[162] The ranger station in Darrington was listed in 1991, while the fire lookouts on Three Fingers, Miners Ridge, and Green Mountain were listed in 1987 and 1988.[162] The Green Mountain lookout was to be removed since its maintenance requires helicopters and other machinery, until passage of the Green Mountain Lookout Heritage Protection Act by the U.S. Congress in 2014 provided funds for a restoration project.[163][164]

Notable people

- Bob Barker, former game show host of The Price Is Right; born in Darrington[165]

- Nels Bruseth, forest ranger, artist, and naturalist[166]

Education

The Darrington School District operates two public schools in the town that enroll 414 students during the 2016–17 school year.[167] It employs 31 teachers and administrations, and 50 other staff members.[168] The district primarily serves Darrington and areas east of Oso, as well as areas in Skagit County that are near the Sauk-Suiattle Reservation.[169][170] The town's elementary school, serving kindergarten through eight grade, was opened in 1990 and shares its campus with the high school.[168][171] The mascot for the school is the Darrington Loggers, named after the town's historic principal industry. Loggers teams have won state championships in various sports during the 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s.[172]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Darrington is located along State Route 530, which travels 28 miles (45 km) west towards Arlington and north to State Route 20 at Rockport.[173][174] The highway carries a daily average of approximately 3,300 vehicles west of the town and 2,300 vehicles north of the town towards the Sauk-Suiattle Reservation.[175] Darrington has a third highway connection through the Mountain Loop Highway, a backcountry scenic byway that runs 54 miles (87 km) south through the Cascades and west to Granite Falls. It is closed in the winter and is considered unsuitable for commercial traffic, in part due to a 14-mile (23 km) dirt and gravel section.[176][177]

The area is also served by Community Transit, the main public transportation agency for most of Snohomish County. Route 230 connects Darrington to Oso, Arlington, and a transit center in Smokey Point twice a day during rush hour.[178][179] The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe operates a bus route serving Darrington, its reservation, and Concrete. It has six daily round trips and launched in 2016 with grants from the state and federal governments.[180]

The Whitehorse Trail, a recreational trail for hikers, cyclists, and horseback riders, is being developed by the county government to connect Darrington with Arlington. It follows the Northern Pacific's 1901 route, sold to the county in 1993.[181][182] The town government operates a small airport, Darrington Municipal Airport, which has a single paved runway suitable for general aviation and other activities.[183]

Utilities

Electric power for Darrington residents and businesses is provided by the Snohomish County Public Utility District (PUD), a consumer-owned public utility that serves all of Snohomish County.[184] The Hampton mill operates a small biomass cogeneration plant in Darrington that produces electricity from steam power by burning wood from the Hampton Lumber sawmill.[185] The 7 MW plant was installed in 2006 after an earlier proposal by the National Energy Systems Company (NESCO) for a similar plant that would have generated up to 20 MW was rejected.[186] The NESCO proposal was withdrawn in 2004 over local concerns about air pollution and environmental degradation to the nearby National Forest lands.[187][188] The town lacks natural gas service and relies on wood-burning stoves for building heat, some of which have been replaced by the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency due to their impact on air quality.[189][190] Ziply Fiber is the only land-based provider of Internet and telephone service to Darrington, using a fiber-optic cable laid along State Route 530.[191] The state government awarded a $16.5 million grant in 2022 to improve broadband and fiber service in northern Snohomish County, including Darrington.[192]

The town government provides water from a pair of wells, and water treatment, to 534 structures.[193] Darrington is one of several small communities in Snohomish County without a municipal sewer system, instead relying on septic tanks.[194][195] The town government has considered installing a sewage system several times in the 1990s and 2000s, but those plans have stalled due to the $6.5 million cost (as estimated in 2000) and the land needed for a treatment plant.[64] Solid waste and recycling collection is contracted out by the town government to Waste Management.[189]

Health care

Darrington's nearest general hospital is the Cascade Valley Hospital in Arlington.[196] The town also has a medical clinic operated by Skagit Regional Health and staffed by a single doctor.[197] The clinic was established in 1958 and operated by Cascade Valley Hospital until it was absorbed into the Skagit system.[198] The town has periodically gone for years without a doctor, notably substituting a registered nurse to provide the majority of medical care in the early 1970s.[199]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Decennial Census Tables". United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Darrington, Washington". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Oakley, Janet (January 17, 2009). "Darrington — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Hollenbeck, Jan L.; Moss, Madonna (1987). A Cultural Resource Overview: Prehistory, Ethnography and History: Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. United States Forest Service. pp. 135–139, 156–157. OCLC 892024380. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via HathiTrust.

- Poehlman, Elizabeth S. (1979). Darrington: Mining Town/Timber Town. Shoreline, Washington: Gold Hill Press. pp. 18–19. LCCN 78-75242. OCLC 34948805.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 35–37.

- Hastie, Thomas P.; Batey, David; Sisson, E.A.; Graham, Albert L., eds. (1906). "Chapter VI: Cities and Towns". An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties. Chicago: Interstate Publishing Company. pp. 408, 461. LCCN 06030900. OCLC 11299996. Retrieved March 1, 2019 – via The Internet Archive.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 21–23.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 38–40.

- Beckey, Fred W. (2003) [1973]. Cascade Alpine Guide Vol. 2: Stevens Pass to Rainy Pass. Cascade Alpine Guide (3rd ed.). The Mountaineers Books. p. 29. ISBN 0-89886-838-6. OCLC 52517872. Retrieved March 9, 2019 – via Google Books.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 40–41.

- Poehlman, Elizabeth S. (August 2, 1972). "Railways prominent in Darrington past". The Arlington Times. p. 21. Retrieved February 27, 2019 – via Small Town Papers.

- "Darrington history dates back to 1888". The Arlington Times. August 2, 1972. p. 21.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 59–61.

- "How local towns got their names". The Arlington Times. July 3, 2002. p. A6. Retrieved March 9, 2019 – via Google News Archive.

- Johnsrud, Byron (August 27, 1972). "There's a touch of the South about bucolic Darrington". The Seattle Times. pp. 8–9.

- Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington Geographic Names. University of Washington Press. p. 63. JSTOR 40474558. OCLC 1963675. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via HathiTrust.

- Beckey (2003), p. 129.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 42.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 47–50.

- Whitfield, William M. (1926). History of Snohomish County, Washington. Chicago: Pioneer Historical Publishing Company. pp. 552–556. OCLC 8437390. Retrieved March 1, 2019 – via HathiTrust.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 43.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 46.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 53–55.

- "Japanese Will Be Put Under Protection". Oregon Statesman. June 15, 1910. p. 4. Retrieved March 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Japanese Envoy Asked to Act in Darrington Case". The Seattle Times. June 16, 1910. p. 4.

- "Darrington Mill Company to Ask For Injunction". The Seattle Times. June 18, 1910. p. 1.

- "No Injunction to Protect Japanese". The Tacoma Times. June 17, 1910. p. 6.

- "Wait For Departure of Prince Fushimi". The Billings Gazette. June 19, 1910. p. 3. Retrieved March 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Oakley, Janet (December 13, 2010). "Darrington incorporates as a fourth-class town on October 15, 1945". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 104.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 74–75, 102–104.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 156.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 157.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 158–159.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 140.

- Stevick, Eric (May 15, 2006). "A House Shares its Past". The Everett Herald. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Cameron, David A. (March 4, 2008). "A key part of the work to build the scenic Mountain Loop Highway linking Granite Falls to Darrington (Snohomish County) begins on March 23, 1936". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 119.

- Cameron, David A.; LeWarne, Charles P.; May, M. Allan; O'Donnell, Jack C.; O'Donnell, Lawrence E. (2005). Snohomish County: An Illustrated History. Index, Washington: Kelcema Books LLC. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-9766700-0-1. OCLC 62728798.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 160.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 74.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 107–108.

- Swaney, Aaron (September 4, 2015). "River Time Brewing opens in downtown Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (August 19, 2011). "New community center gym floor ready for Darrington's high school athletes". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 75.

- Bergsman, Jerry (August 8, 1981). "Comprehensive plan paves way for new hangar at airport". The Seattle Times. p. F7.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 162–163.

- Muhlstein, Julie (April 26, 2020). "An open-pit mine that wasn't: Ridge near Glacier Peak spared". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Larsen, Richard W. (November 17, 1991). "A vision for Darrington". The Seattle Times. p. A21. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Reed, Claudia (September 2, 1993). "New hiking trail may go alongside an old rail line". The Seattle Times. p. 4.

- Poehlman (1979), p. 165.

- "Portland company will buy Darrington sawmill". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. October 19, 2001. p. E1.

- Werner, Larry (September 22, 1990). "Timber town of Darrington knows it will survive". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A10.

- Pryne, Eric (March 28, 1993). "Big trees, big questions". The Seattle Times. p. A1.

- Erb, George (August 15, 1999). "Ruling spikes timber sales". Puget Sound Business Journal. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Logging partnership formed for Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest". The Everett Herald. Associated Press. July 10, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Broom, Jack (February 27, 1988). "Logging trucks roll to protest forest-use plan". The Seattle Times. p. A8.

- Dietrich, Bill (August 6, 1991). "Lumbering towns now take light steps". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Pryne, Eric (June 1, 1993). "A plan blooms in Darrington". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Whitely, Peyton (August 16, 2003). "Buyers scarce for controversial Darrington houses". The Seattle Times. p. H16. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Burkitt, Janet (July 17, 2000). "Lure of past clouds town's future". The Seattle Times. p. B1.

- Brooks, Diane (October 22, 2003). "Idea for regional swim center surfaces again in Darrington". The Seattle Times. p. H8.

- Heffter, April 7, 2004. "Marysville-Arlington area drives for a NASCAR track". The Seattle Times. p. H20. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Whitely, Peyton (April 21, 2004). "River taking a neighborhood". The Seattle Times. p. H23.

- Hodges, Jane (June 2, 2004). "Area's small businesses feeling pinch". The Seattle Times. p. H23.

- Gilmore, Susan (June 27, 2008). "Darrington, Granite Falls to celebrate reopening of Mountain Loop Highway". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Arlington, Darrington companies announce layoffs coming in December". The Everett Herald. October 14, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (December 7, 2010). "Darrington's modest budget covers town's needs". The Everett Herald. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Johnson, Kirk (July 23, 2014). "Washington Mudslide Report Cites Rain, but Doesn't Give Cause or Assign Blame". The New York Times. p. A13. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Doughton, Sandi (December 22, 2015). "New analysis shows Oso landslide was no fluke". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Burns, Frances (April 16, 2014). "Medical examiner: 39 now confirmed dead in Washington State mudslide". United Press International. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Lacitis, Erik (March 26, 2014). "A small town's embrace: In Darrington, 'we help people out'". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Catchpole, Dan (March 30, 2014). "Grit and heart keep Darrington going". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- King, Rikki (June 20, 2015). "In Darrington, a slide reunion means laughter, tears". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (June 20, 2014). "Highway 530 open to two-way traffic at mudslide site". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- King, Rikki (September 27, 2014). "43 trees mark lives lost along Highway 530 in Oso". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Catchpole, Dan (April 25, 2014). "For Darrington, disaster is a blow it can little afford". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Cornwell, Paige (March 18, 2015). "Oso landslide donations: Where the millions went". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (June 19, 2014). "Ads to boost tourism in Stillaguamish Valley begin airing". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (July 30, 2014). "Darrington businesses are ready to be 'mobbed'". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Broom, Jack (March 17, 2015). "In Darrington, 'recovery is a marathon, not a sprint'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (December 2, 2015). "Officials to present Oso mudslide economic recovery plan". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "A brief history of Darrington and Oso". KING 5 News. March 26, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "2018 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- Snohomish County Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, Volume 2: Planning Partner Annexes (Report). Snohomish County. September 2015. p. 4-1. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Bryan, Zachariah (February 23, 2019). "Buried in 3 feet of snow, Darrington takes care of itself". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (May 15, 2018). "Cloaked in ice, Snohomish County's volcano is a future danger". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Modeling a Magnitude 7.1 Earthquake on the Darrington–Devils Mountain Fault Zone in Skagit County" (PDF). Washington State Department of Natural Resources. 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Broughton, W. A. (1942). Inventory of Mineral Properties in Snohomish County, Washington (PDF). Washington State Department of Conservation and Development. p. 7. OCLC 4409664. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- "Climate of Washington". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Period of Record Monthly Climate Summary: Darrington, Washington (451992)". Western Regional Climate Center. April 30, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. European Geosciences Union. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Davis, Jim (April 1, 2014). "Darrington sawmill hopes to avoid shutting down". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Hayes, Katie (July 11, 2021). "Hampton Lumber makes big purchase for small-town Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- "Hampton reopens Washington sawmill". Portland Business Journal. March 28, 2003. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- "Hampton completes purchase of Darrington sawmill". Puget Sound Business Journal. February 7, 2002. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (August 21, 2011). "A battle for 'the greatest good'". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (July 20, 2017). "Darrington-bound? Check out these great dining options". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Swaney, Aaron (September 4, 2015). "River Time Brewing opens in downtown Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (September 6, 2018). "Sauk-Suiattle Tribe's casino and bingo hall near completion". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: Darrington, Washington". American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. September 15, 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Work Destination Report — Where Workers are Employed Who Live in the Selection Area — by Places (Cities, CDPs, etc.)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via OnTheMap.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Washington: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019". United States Census Bureau. May 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Taylor, Chuck (February 1, 2013). "Snohomish County demographics from the census". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Duncan, Don (October 6, 1980). "Darrington: That feisty logging spirit mingles with a shot of heady mountain air and toe-tappin' bluegrass". The Seattle Times. p. B6.

- Muhlstein, Julie (April 8, 2014). "N.C. town with deep kinship to hold fundraiser". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Denn, Rebekah (December 19, 1998). "Residents fiercely loyal to town". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. D1.

- "Darrington Comprehensive Plan, 2015 Update" (PDF). Town of Darrington. 2015. p. 39. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- United States Census Bureau (May 2014). "Per Capita Income for Incorporated Cities in Washington State" (PDF). Washington State Department of Ecology. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Thompson, Lynn (March 17, 2007). "Town grieves, takes stock after 3 deaths". The Seattle Times. p. H16. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: Darrington town, Washington" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved February 24, 2019 – via Puget Sound Regional Council.

- "Financial Statements Audit Report: Town of Darrington". Washington State Auditor. December 28, 2017. pp. 4, 24. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Snohomish County 2012 Buildable Lands Report". Snohomish County. June 12, 2013. p. 4-5. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Town Council". Town of Darrington. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (October 9, 2015). "Ronning challenging Rankin in Darrington mayoral race". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (May 25, 2017). "Darrington celebrates centennial of the town's cemetery". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Local Government Departments". Town of Darrington. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Emergency Services". Town of Darrington. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Darrington Comprehensive Plan (2015), pp. 73–79.

- Fiege, Gale (December 4, 2008). "Darrington celebrates its revamped library". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Sno-Isle Libraries 2016–2025 Capital Facilities Plan" (PDF). Sno-Isle Libraries. 2016. p. 23. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Davis-Leonard, Ian (November 14, 2020). "Darrington post office's limited access has residents peeved". The Everett Herald. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- Haglund, Noah (January 24, 2017). "At 21, Nate Nehring is youngest to serve on County Council". The Everett Herald. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Washington State Legislative & Congressional District Map (PDF) (Map). Washington State Redistricting Commission. February 7, 2012. Puget Sound inset. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Brunner, Jim (May 27, 2015). "Monroe GOP lawmaker plans to run against Rep. DelBene". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Cornfield, Jerry; Catchpole, Dan (November 14, 2016). "Trump voters elated but most of Snohomish County followed state". The Everett Herald. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Tompkins, Caitlin (September 1, 2017). "Darrington comes together in wake of vandals' destruction". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Garnick, Coral (March 28, 2014). "Darrington comes together following tragedy". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Alexander, Brian (June 17, 2005). "Bad news from 'down below': Darrington's only bank will close". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Muhlstein, Julie (July 1, 2007). "Home cooking is part of grieving in Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Hatcher, Candy (December 8, 2000). "Everyone is family". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1.

- Muhlstein, Julie (March 25, 2014). "Darrington: A family that pulls together". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Broom, Jack (June 19, 2014). "Rodeo upgrades could help Darrington's mudslide recovery". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Catchpole, Dan (May 21, 2014). "Outside money keeps Darrington rodeo alive". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Johnson, Kirk (July 16, 2014). "Months After Washington Landslide, Hopeful Steps Forward". The New York Times. p. A11. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Johnson, Della (June 19, 1966). "Darrington: It's small, but its people and beauty make it big". The Seattle Times. p. 2.

- "Month-long fest in Stillaguamish area". The Seattle Times. July 30, 1972. p. D10.

- Fiege, Gale (July 15, 2016). "At 40 years, Darrington's bluegrass festival still going strong". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (July 15, 2015). "Darrington Bluegrass Festival about music and family". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Stout, Gene (August 4, 2015). "Summer Meltdown way more than a jam band's backyard party". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Thompson, Evan (August 13, 2018). "Summer Meltdown: Musical ecstasy in Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Carlson, Mark (May 14, 2020). "Both of Darrington's iconic summer music festivals canceled". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Broom, Jack (May 13, 2014). "Shaken Darrington to keep its community celebrations". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "North Cascadian Travelers' Guide 2018" (PDF). The Concrete Herald. 2018. pp. 38–44. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Poehlman (1979), pp. 110–112.

- "This week in history – from The Arlington Times archives". The Arlington Times. August 27, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Haglund, Noah (January 9, 2019). "Forest ranger's retirement is blocked by border-wall standoff". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Hill, Craig (August 17, 2014). "Darrington: 'A lifetime is not enough' to do it all". The News Tribune. p. E1. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (July 17, 2015). "A day-tripper's guide to resilient Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Broom, Jack (October 24, 2014). "Darrington to celebrate as road to wilderness opens again". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Darrington Comprehensive Plan (2015), p. 96.

- Bray, Kari (November 16, 2015). "Recreation opportunities expanding in Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Parks". Town of Darrington. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (August 4, 2009). "Costly Darrington ballpark attracts few visitors". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Whitehorse Community Park". Snohomish County Parks and Recreation. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Brooks, Diane (July 16, 2003). "Contest targets Darrington". The Seattle Times. p. H28. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (July 6, 2016). "Darrington historians, UW students create mudslide archive". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- "Designated historic sites in Snohomish County". The Everett Herald. July 5, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (April 7, 2014). "Mountain lookout is saved, cheering Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Song, Kyung M. (April 7, 2014). "Fire lookout near Darrington saved by Congress". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- Vejnoska, Jill (December 12, 2017). "Happy 94th birthday, Bob Barker. Here's why you rock!". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (February 12, 2011). "Explore history of lookouts". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- "Public School District Directory Information: Sultan School District". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (February 27, 2016). "Darrington High School grads now teaching the next generation". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Snohomish County School Districts Map (PDF) (Map). Snohomish County. December 21, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Washington State K-12 School Districts (PDF) (Map). Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- Turner, Andy (August 15, 1990). "State of the art: D'ton school opening". The Arlington Times. p. 1.

- Fiege, Gale (November 14, 2011). "A home for the best of Darrington's Loggers". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Broom, Jack (May 8, 2014). "530 slide bypass road opens to wider use". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Bray, Kari; King, Rikki (April 13, 2017). "Highway 530 reopens, but Darrington residents are wary". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- 2016 Annual Traffic Report (PDF) (Report). Washington State Department of Transportation. 2017. p. 207. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Sheets, Bill (April 6, 2014). "Alternate route to Darrington scenic, slow". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (October 2, 2016). "Study to examine Mountain Loop Highway improvements". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Watanabe, Ben (April 23, 2023). "Want ride-hailing at bus prices in Arlington? Let Community Transit know". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- "Route 230: Darrington–Smokey Point". Community Transit. March 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- Bray, Kari (November 7, 2016). "Sauk-Suiattle Tribe's new bus goes to Concrete, Darrington". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Railroad land to add 27 miles to trail system". The Seattle Times. November 11, 1993. p. 4.

- Bray, Kari (December 28, 2015). "Work to begin on another 9.5 miles of Whitehorse Trail". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Darrington Municipal Airport Economic Profile" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. March 22, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Quick Facts". Snohomish County Public Utility District. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Power Supply: Biomass". Snohomish County Public Utility District. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- Reese, Phil; Carlson, Bill (May 15, 2007). "Experts ponder future of biomass industry". Power Magazine. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- Fetters, Eric (July 30, 2004). "Darrington electric plant shelved". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- Morris, Scott (March 14, 2004). "Feds join Darrington power plant battle". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- Darrington Comprehensive Plan (2015), pp. 107–108.

- Fiege, Gale (February 1, 2009). "Darrington cleans up its air, one wood stove at a time". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Bray, Kari (March 10, 2015). "Permanent cables link Arlington, Darrington once again". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Allison, Jacqueline (January 25, 2022). "$16M grant to speed up broadband to north Snohomish County". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- Darrington Comprehensive Plan (2015), p. 78.

- Darrington Comprehensive Plan (2015), p. 18.

- "Utilities". Snohomish County General Policy Plan (Report). Snohomish County. June 10, 2015. p. UT-5. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Interactive map of hospitals in King, Pierce, Snohomish counties". The Seattle Times. November 30, 2013. Archived from the original on January 27, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Fiege, Gale (May 17, 2013). "Darrington's sole doctor is always in". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Darrington Clinic Guild". Cascade Valley Hospital. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Darrington's nurse-practitioner system may be solution for other small towns". The Seattle Times. May 25, 1973. pp. A10–A11.

External links

- Official website

- Tarheels in the Northwest, KCTS-TV (PBS), 1979 – via American Archive of Public Broadcasting