Economy of Uganda

The economy of Uganda has a great potential and appears poised for rapid growth and development.[18] Uganda is endowed with significant natural resources, including ample fertile land, regular rainfall, and mineral deposits.

Kampala, the financial centre of Uganda | |

| Currency | Ugandan shilling (USh) |

|---|---|

| 1 July – 30 June | |

Trade organisations | AU, EAC, COMESA, WTO |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | 90th (nominal, 2017) |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP by sector |

|

| 3.2% (2019)[3] | |

| 19.1% (31 December 2017 est.)[5] | |

Population below poverty line | |

| 42.8 medium (2016)[8] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

Main industries | sugar processing, brewing, tobacco, cotton textiles, cement, steel production[6] |

| External | |

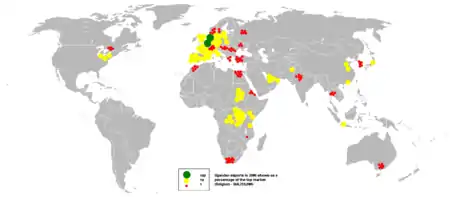

| Exports | |

Export goods | coffee, fish and fish products, tea, cotton, flowers, horticultural products, gold[6] |

Main export partners | |

| Imports | |

Import goods | capital equipment, vehicles, petroleum, medical supplies, cereals[6] |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | $10.909 billion (2016)[14] |

Gross external debt | $7.163 billion (31 December 2017 est.)[6] |

| Public finances | |

| $11.2 billion ($3.8 billion, domestic) (2018)[15] | |

| –4.1% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[6] | |

| Revenues | $3.98 billion (2017)[16] |

| Expenses | $7.66 billion (2017)[16] |

| Economic aid | $3.68 billion (2017)[16] |

| Standard & Poor's: | |

Chronic political instability and erratic economic management since the implementation of self-rule has produced a record of persistent economic decline that has left Uganda among the world's poorest and least-developed countries.[19] The informal economy, which is predominantly female, is broadly defined as a group of vulnerable individuals without protections in regards to their work.[20] Women face a plethora of barriers specific to gender when attempting to access the formal economy of Uganda, and research revealed prejudice against lending to women in the informal sector.[21][22] The national energy needs have historically exceeded the domestic energy generation, though large petroleum reserves have been found in the country's west.[23]

After the turmoil of the Amin period, the country began a program of economic recovery in 1981 that received considerable foreign assistance. From mid-1984 onward, overly expansionist fiscal and monetary policies and the renewed outbreak of civil strife led to a setback in economic performance.[24]

The economy has grown since the 1990s; real gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an average of 6.7% annually during the period 1990–2015,[25] whereas real GDP per capita grew at 3.3% per annum during the same period.[25] During this period, the Ugandan economy experienced economic transformation: the share of agriculture value added in GDP declined from 56% in 1990 to 24% in 2015; the share of industry grew from 11% to 20% (with manufacturing increasing at a slower pace, from 6% to 9% of GDP); and the share of services went from 32% to 55%.[25]

International trade and finance

Since assuming power in early 1986, Museveni's government has taken important steps toward economic rehabilitation. The country's infrastructure, notably its transport and communications systems which were destroyed by war and neglect, is being rebuilt. Recognizing the need for increased external support, Uganda negotiated a policy framework paper with the IMF and the World Bank in 1987. Uganda subsequently began implementing economic policies designed to restore price stability and sustainable balance of payments, improve capacity utilization, rehabilitate infrastructure, restore producer incentives through proper price policies, and improve resource mobilization and allocation in the public sector. These so-called Structural Adjustment Programs greatly improved the shape of the Ugandan economy, but did not lead to economic growth in the first decade after their implementation. Since 1995, Uganda has experienced rapid economic growth, but it is not clear to what extent this positive development can be attributed to Structural Adjustment.[26] Uganda is a member of the World Trade Organization, since 1 January 1995 and a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, from 25 October 1962.[27]

Currency

Uganda began issuing its own currency in 1966 through the Bank of Uganda.[28]

Agriculture

Agricultural products supply a significant portion of Uganda's foreign exchange earnings, with coffee alone, of which Uganda is Africa's second largest producer after Ethiopia,[29] accounting for about 17% of the country's exports in 2017 and earning the country US$545 million.[29] Exports of apparel, hides, skins, vanilla, vegetables, fruits, cut flowers, and fish are growing, while cotton, tea, and tobacco continue to be mainstays.[30]

Uganda produced in 2018:

- 3.9 million tons of sugarcane;

- 3.8 million tons of plantain (4th largest producer in the world, losing only to Congo, Ghana and Cameroon);

- 2.9 million tons of maize;

- 2.6 million tons of cassava;

- 1.5 million tons of sweet potato (7th largest producer in the world);

- 1.0 million tons of bean;

- 1.0 million tons of vegetable;

- 532 thousand tons of banana;

- 360 thousand tons of onion;

- 298 thousand tons of sorghum;

- 260 thousand tons of rice;

- 245 thousand tons of sunflower seed;

- 242 thousand tons of peanut;

- 211 thousand tons of coffee (10th largest producer in the world);

- 209 thousand tons of millet;

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products, like cotton (87 thousand tons), tea (62 thousand tons), tobacco (35 thousand tons) and cocoa (27 thousand tons).[31]

Transportation

As of 2017, Uganda had about 130,000 kilometres (80,778 mi) of roads, with approximately 5,300 kilometres (3,293 mi) (4 percent) paved.[32] Most paved roads radiate from Kampala, the country's capital and largest city.[33]

As of 2017, Uganda's metre gauge railway network measures about 1,250 kilometres (777 mi) in length. Of this, about 56% (700 kilometres (435 mi)), is operational. A railroad originating at Mombasa on the Indian Ocean connects with Tororo, where it branches westward to Jinja, Kampala, and Kasese and northward to Mbale, Soroti, Lira, Gulu, and Pakwach. The only railway line still operating, however, is the one to Kampala.[32]

Uganda's important link to the port of Mombasa is now mainly by road, which serves its transport needs and also those of neighboring Rwanda, Burundi, parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan.[34]

An international airport is at Entebbe on the northern shores of Lake Victoria, about 41 kilometres (25 mi) south of Kampala.[35] In January 2018, the government of Uganda began the construction of Kabaale International Airport, in the Western Region of Uganda. This will be Uganda's second international airport, which is planned to facilitate the construction of an oil refinery and boost tourism.[36]

The transport union Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union (ATWGU) is one of the more powerful trade unions in the country with about 100,000 members, many of whom are informal workers.[37]

Communications

The Uganda Communications Commission regulates communications, primarily "delivered through an enabled private sector." The companies it regulates include television networks, radio stations, mobile network operators, and fixed-line telephone companies.[38]

Mining and petroleum

Uganda's predominant mineral occurrences are gold, tungsten, tin, beryl, and tantalite in the south; tungsten, clay, and granite between latitude zero and two degrees north; and gold, mica, copper, limestone, and iron in the north.[39]

In late 2012, the government of Uganda was taken to court over value added tax that it placed on goods and services purchased by Tullow Oil, a foreign oil company operating in the country at the time.[40] The court case was heard at an international court based in the United States. The Ugandan government insisted that Tullow could not claim taxes on supplies as recoverable costs before oil production starts.[41] Sources from within the government reveal that the main concern at present is the manner in which millions of dollars have been lost in the past decade, money that could allegedly have stayed in Uganda for investment in the public sector; a Global Financial Integrity report recently revealed that illicit money flows from Uganda between 2001 and 2012 totalled $680 million.[41] Tullow Oil was represented in the court case by Kampala Associated Advocates, whose founder is Elly Kurahanga, the President of Tullow Uganda.[40] A partner at Kampala Associated Advocates, Peter Kabatsi, was also Uganda's solicitor general between 1990 and 2002, and he has denied claims that he negotiated contracts with foreign oil firms during his time in this role.[40]

In June 2015, the Ugandan government and Tullow Oil settled a longstanding dispute regarding the amount of certain capital gains taxes that the company owed to the government.[42] The government claimed that the company owed US$435 million.[43] The claim, however, was settled for US$250 million.[42]

In April 2018, the government signed agreements with Albertine Graben Refinery Consortium, an International consortium led by General Electric of the United States, to build a 60,000 barrels-per-day Uganda Oil Refinery in Western Uganda. The cost of the development is budgeted at about US$4 billion.[44][45]

Women in the Economy

The agriculture sector of the Ugandan economy, which composes roughly 40% of the country's GDP, is largely fulfilled by women laborers, especially in managing products, marketing, and the crop sub-sector.[46] 76% of women work in the agriculture sector and roughly 66% of men do, and women provide for 80% of food crops and 60% of traditional exports such as coffee or tea.[21] In the formal, non-agricultural economy, men constitute 61% of the workforce, whereas women predominate the informal economy, and this can be attributed to the lack of equity between men and women in the country.[46] The Uganda Bureau of Statistics reported, when looking at the urban workforce in 2015, 88.6% of women were employed informally, and 84.2% of men were.[47] Women are unable to enter into certain sectors, especially in the formal economy, due to the inability to provide substantial initial funding, and remain in the trade and service sectors of the economy. Comparatively, men dominate the more profitable sectors, such as manufacturing.[21] Women traders make up 70% of those in markets and 40% in shops in addition to dominating other sectors such as the service industry, crafts, and tailoring.[48]

Women are often undervalued in data compilation, particularly when considering their role in their domestic home lives. For example, women commonly match the contribution of their husbands to their familial income, if not provide more, when taking into consideration the value of their labor and the profits made from selling excess food.[21] Urban women on average earn between 50% and 70% of a household's income.[48] Women are also discredited in data collection due to biases of data collectors resulting in inaccurate reports, as well as income being measured per house, rather than separating by gender.[21] The barriers women face in furthering their entrepreneurial careers are different from those faced by men; this is inherent in the biased culture and institutions plaguing Uganda despite the passing of somewhat progressive policies, especially with the 1985 transition of government to the National Resistance Movement party.[49]

Data

| Year | GDP

(in bn. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 5.9 | 525 | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | ||||

| 1982 | n/a | ||||

| 1983 | n/a | ||||

| 1984 | n/a | ||||

| 1985 | n/a | ||||

| 1986 | n/a | ||||

| 1987 | n/a | ||||

| 1988 | n/a | ||||

| 1989 | n/a | ||||

| 1990 | n/a | ||||

| 1991 | n/a | ||||

| 1992 | n/a | ||||

| 1993 | n/a | ||||

| 1994 | n/a | ||||

| 1995 | n/a | ||||

| 1996 | n/a | ||||

| 1997 | 44.2% | ||||

| 1998 | |||||

| 1999 | |||||

| 2000 | |||||

| 2001 | |||||

| 2002 | |||||

| 2003 | |||||

| 2004 | |||||

| 2005 | |||||

| 2006 | |||||

| 2007 | |||||

| 2008 | |||||

| 2009 | |||||

| 2010 | |||||

| 2011 | |||||

| 2012 | |||||

| 2013 | |||||

| 2014 | |||||

| 2015 | |||||

| 2016 | |||||

| 2017 | |||||

| 2018 | |||||

| 2019 | |||||

| 2020 | |||||

| 2021 |

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Global Economic Prospects, January 2020 : Slow Growth, Policy Challenges" (PDF). openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 147. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Biryabarema, Elias (3 October 2017). "Uganda central bank lowers key lending rate to 9.5 percent". Reuters.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "AFRICA :: UGANDA". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Uganda". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate) - Uganda". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- "Labor force, total - Uganda". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Uganda". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- The EastAfrican (28 October 2019). "Rwanda Drops In Ranking But Remains Top In Region In Ease Of Doing Business". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- UNCTAD (November 2017). "Uganda: Foreign Investment: Foreign Direct Investment". Export Entreprises SA Quoting UNCTAD. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Nakaweesi, Dorothy (27 June 2018). "Uganda Shilling: A currency in free-fall". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- KPMG (June 2017). "Uganda Budget Brief 2017: Economic Commentary" (PDF). Nairobi: KPMG Kenya. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "S&P lowers Uganda sovereign credit rating to B from B+". Reuters. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- World Bank (December 2017). "Uganda Economic Update, 10th Edition, December 2017 : Accelerating Uganda's Development, Ending Child Marriage, Educating Girls". Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Staff Writer (31 May 2016). "The richest and poorest countries in Africa". Johannesburg: Businesstech.co.za. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Decent work and the informal economy - ILO 2002 | capacity4dev.eu". europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Snyder, Margarget (2000). Women in African Economies: From Burning Sun to Boardroom. Kampala: Fountain Publishers Ltd. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9970-02-187-7.

- Okurut, F. N.; Schoombee, A.; Berg, S. Van Der (2005). "Credit Demand and Credit Rationing in the Informal Financial Sector in Uganda1". South African Journal of Economics. 73 (3): 482–497. doi:10.1111/j.1813-6982.2005.00033.x. hdl:10019.1/50308. ISSN 1813-6982.

- John Aglionby (27 April 2017). "Uganda's oil reserves bring promise of work and infrastructure". The Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- CARE International (13 November 2002). "Economic cost of the conflict in Northern Uganda". New York City: ReliefWeb. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- World Bank. "World Development Indicators". Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 332–334. ISBN 9781107507180.

- WTO (8 June 2018). "Uganda and the WTO". Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO). Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Bank of Uganda (8 June 2018). "History of Uganda Currency". Kampala: Bank of Uganda. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Nakaweesi, Dorothy (25 October 2017). "Uganda posts highest coffee export volumes at 4.6 million bags". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- International Trade Administration (8 March 2017). "Uganda - Agriculture". Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Uganda production in 2018, by FAO

- Ministry of Works & Transport (2017). "Key Summary Statistics". Kampala: Uganda Ministry of Works and Transport. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Map of Uganda Showing Main Roads". Dlca.logcluster.org. 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- NCTTCA (2018). "About the Northern Transportation Corridor". Mombasa: Northern Corridor Transit and Transportation Coordination Authority (NCTTCA). Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Globefeed.com (8 June 2018). "Distance between Post Office Building, Kampala Road, Kampala, Uganda and Entebbe International Airport, 5536 Kampala Road, Entebbe, Uganda". Globefeed.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Steenhoff-Snethlage, Erin (11 December 2017). "Second international airport on the way for Uganda". Johannesburg: Ftwonline.co.za. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Schminke, Tobias Gerhard (2019). Labour-centred development and decent work : a structuralist perspective on informal employment and trade union organizing in Uganda. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Saint Mary's University. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- Paul Mugume (23 January 2017). "Uganda Communications Commission Toughens on Local Content Prioritization". Kampala: TCTech Magazine. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Butagira, Tabu (31 August 2012). "Study shows Uganda's vast mineral riches". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Butagira, Tabu (17 December 2012). "Tullow sues government in new tax dispute". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- NorthSouthNews (8 January 2013). "Tullow Oil and Ugandan government in second tax row". NorthSouthNews.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- RTÉ Ireland (22 June 2015). "Tullow pays $250 million to settle Uganda tax dispute out of court". RTÉ.ie. Dublin, Ireland: Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Mason, Rowena (18 April 2011). "Tullow Oil sues Heritage over unpaid Ugandan tax bill". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Olingo, Allan (14 April 2018). "Uganda signs $4 billion refinery plant deal". The EastAfrican. Nairobi. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Musisi, Frederic (8 May 2018). "Uganda signs off Shs4 trillion for US in refinery". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Ellis, Amanda; Manuel, Claire; Blackden, C. Mark (2006). Gender and Economic Growth in Uganda: Unleashing the Power of Women. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. pp. 27–37. ISBN 0-8213-6384-0.

- "2017 Statistical Report" (PDF). Uganda Bureau of Statistics: 169. 2017.

- Lange, Siri (2003). "When women grow wings: Gender relations in the informal economy of Kampala". CMI Report. R 2003: 8: 1–8.

- Guma, Prince Karakire (7 September 2015). "Business in the urban informal economy: barriers to women's entrepreneurship in Uganda". Journal of African Business. 16 (3): 305–321. doi:10.1080/15228916.2015.1081025. S2CID 216149652.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- FY based numbers

External links

- Uganda Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development

- Uganda Investment Authority; Sector analysis reports available

- Economy of Uganda at Curlie

- The Uganda Business Index

- Uganda Business Directory

- Uganda latest trade data on ITC Trade Map

- Uganda Economy Gets Bigger By 20% As of 21 October 2019.