El Dorado

El Dorado (Spanish: [el doˈɾaðo], English: /ˌɛl dəˈrɑːdoʊ/; Spanish for "the golden") is commonly associated with the legend of a gold city, kingdom, or empire purportedly located somewhere in the Americas. Originally, El Hombre Dorado ("The Golden Man") or El Rey Dorado ("The Golden King"), was the term used by the Spanish in the 16th century to describe a mythical tribal chief (zipa) or king of the Muisca people, an indigenous people of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense of Colombia, who as an initiation rite, covered himself with gold dust and submerged in Lake Guatavita.

.jpg.webp)

This Muisca raft figure is on display in the Gold Museum, Bogotá, Colombia.

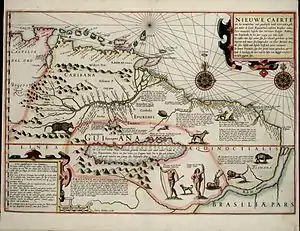

A second location for El Dorado was inferred from rumors, which inspired several unsuccessful expeditions in the late 1500s in search of a city called Manoa on the shores of Lake Parime or Parima. Two of the most famous of these expeditions were led by Sir Walter Raleigh. In pursuit of the legend, Spanish conquistadores and numerous others searched what is today Colombia, Venezuela, and parts of Guyana and northern Brazil, for the city and its fabulous king. In the course of these explorations, much of northern South America, including the Amazon River, was mapped. By the beginning of the 19th century, most people dismissed the existence of the city as a myth.[1]

The legend of the Seven Cities of Gold (Seven Cities of Cibola) led to Francisco Vázquez de Coronado's expedition of 1540 across the New Mexico territory. This became mixed with the stories of El Dorado, which was sometimes said to be one of the seven cities.

Several literary works have used the name in their titles, sometimes as "El Dorado", and other times as "Eldorado".

Muisca

The Muisca people occupied the highlands of Cundinamarca and Boyacá departments of Colombia in two migrations from outlying lowland areas, one starting c. 1270 BC, and a second between 800 BC and 500 BC. At those times, other more ancient civilizations also flourished in the highlands. The Muisca Confederation was as advanced as the Aztec, Maya and Inca civilizations.[2]

In the mythology of the Muisca, Mnya the Gold or golden color, represents the energy contained in the trinity of Chiminigagua, which constitutes the creative power of everything that exists.[3] Chiminigagua is related to Bachué, Cuza, Chibchacum, Bochica, and Nencatacoa.

The tribal ceremony

The original narrative can be found in the rambling chronicle El Carnero of Juan Rodriguez Freyle. According to Freyle, the zipa of the Muisca, in a ritual at Lake Guatavita near present-day Bogotá, was said to be covered with gold dust, which he then washed off in the lake while his attendants threw objects made of gold, emeralds, and precious stones into the lake—such as tunjos.

In 1638, Freyle wrote this account of the ceremony, addressed to the cacique or governor of Guatavita:[Note 1]

The ceremony took place on the appointment of a new ruler. Before taking office, he spent some time secluded in a cave, without women, forbidden to eat salt, or to go out during daylight. The first journey he had to make was to go to the great lagoon of Guatavita, to make offerings and sacrifices to the demon which they worshipped as their god and lord. During the ceremony which took place at the lagoon, they made a raft of rushes, embellishing and decorating it with the most attractive things they had. They put on it four lighted braziers in which they burned much moque, which is the incense of these natives, and also resin and many other perfumes. The lagoon was large and deep, so that a ship with high sides could sail on it, all loaded with an infinity of men and women dressed in fine plumes, golden plaques and crowns. ... As soon as those on the raft began to burn incense, they also lit braziers on the shore, so that the smoke hid the light of day.

At this time, they stripped the heir to his skin, and anointed him with a sticky earth on which they placed gold dust so that he was completely covered with this metal. They placed him on the raft ... and at his feet they placed a great heap of gold and emeralds for him to offer to his god. In the raft with him went four principal subject chiefs, decked in plumes, crowns, bracelets, pendants and ear rings all of gold. They, too, were naked, and each one carried his offering ... when the raft reached the centre of the lagoon, they raised a banner as a signal for silence.

The gilded Indian then ... [threw] out all the pile of gold into the middle of the lake, and the chiefs who had accompanied him did the same on their own accounts. ... After this they lowered the flag, which had remained up during the whole time of offering, and, as the raft moved towards the shore, the shouting began again, with pipes, flutes and large teams of singers and dancers. With this ceremony the new ruler was received, and was recognized as lord and king.

This is the ceremony that became the famous El Dorado, which has taken so many lives and fortunes.

There is also an account, titled The Quest of El Dorado, by poet-priest and historian of the Conquest Juan de Castellanos, who had served under Jiménez de Quesada in his campaign against the Muisca, written in the mid-16th century but not published until 1850:[5]

An alien Indian, hailing from afar,

Who in the town of Quito did abide.

And neighbor claimed to be of Bogata,

There having come, I know not by what way,

Did with him speak and solemnly announce

A country rich in emeralds and gold.

Also, among (us) the things which them engaged,

A certain king he told of who, disrobed,

Upon a lake was wont, aboard a raft,

To make oblations, as himself had seen,

His regal form overspread with fragrant oil

On which was laid a coat of powdered gold

From sole of foot unto his highest brow,

Resplendent as the beaming of the sun.

Arrivals without end, he further said,

Were there to make rich votive offerings

Of golden trinkets and of emeralds rare

And divers other of their ornaments;

And worthy credence these things he affirmed;

The soldiers, light of heart and well content,

Then dubbed him El Dorado, and the name

By countless ways was spread throughout the world.

In his Historia general y natural de las Indias (1535, expanded in 1851 from his previously unpublished papers), Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés stated:[6]

He went about all covered with powdered gold, as casually as if it were powdered salt. For it seemed to him that to wear any other finery was less beautiful, and that to put on ornaments or arms made of gold worked by hammering, stamping, or by other means, was a vulgar and common thing.

In the Muisca territories, there were a number of natural locations considered sacred, including lakes, rivers, forests and large rocks. People gathered here to perform rituals and sacrifices mostly with gold and emeralds. Important lakes were Lake Guatavita, Lake Iguaque, Lake Fúquene, Lake Tota, the Siecha Lakes, Lake Teusacá and Lake Ubaque.[2]

From ritual to myth and metaphor

The concept of El Dorado underwent several transformations, and eventually accounts of the previous mytha legendary story in which precious stones were found in fabulous abundance along with gold coins—were also combined with those of a legendary lost city. The resulting El Dorado myth enticed European explorers for two centuries. Among the earliest stories was the one told on his deathbed by Juan Martinez, a captain of munitions for Spanish adventurer Diego de Ordaz, who claimed to have visited the city of Manoa. Martinez had allowed a store of gunpowder to catch fire and was condemned to death, however his friends let him escape downriver in a canoe. Martinez then met with some local people who took him to the city:

The canoa [sic] was carried down the stream, and certain of the Guianians met it the same evening; and, having not at any time seen any Christian nor any man of that colour, they carried Martinez into the land to be wondered at, and so from town to town, until he came to the great city of Manoa, the seat and residence of Inga the emperor. The emperor, after he had beheld him, knew him to be a Christian, and caused him to be lodged in his palace, and well entertained. He was brought thither all the way blindfold, led by the Indians, until he came to the entrance of Manoa itself, and was fourteen or fifteen days in the passage. He avowed at his death that he entered the city at noon, and then they uncovered his face; and that he traveled all that day till night through the city, and the next day from sun rising to sun setting, ere he came to the palace of Inga. After that Martinez had lived seven months in Manoa, and began to understand the language of the country, Inga asked him whether he desired to return into his own country, or would willingly abide with him. But Martinez, not desirous to stay, obtained the favour of Inga to depart.[7]

The fable of Juan Martinez was founded on the adventures of Juan Martin de Albujar, well known to the Spanish historians of the Conquest; and who, in the expedition of Pedro de Silva (1570), fell into the hands of the Caribs of the Lower Orinoco.[1]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Europeans, still fascinated by the New World, believed that a hidden city of immense wealth existed. Numerous expeditions were mounted to search for this treasure, all of which ended in failure. The illustration of El Dorado's location on maps only made matters worse, as it made some people think that the city of El Dorado's existence had been confirmed. The mythical city of El Dorado on Lake Parime was marked on numerous maps until its existence was disproved by Alexander von Humboldt during his Latin America expedition (1799–1804).

Meanwhile, the name of El Dorado came to be used metaphorically of any place where wealth could be rapidly acquired. It was given to El Dorado County, California, and to towns and cities in various states. It has also been anglicized to the single word Eldorado, and is sometimes used in product titles to suggest great wealth and fortune, such as the Cadillac Eldorado line of luxury automobiles.

El Dorado is also sometimes used as a metaphor to represent an ultimate prize or "Holy Grail" that one might spend one's life seeking. It could represent true love, heaven, happiness, or success. It is used sometimes as a figure of speech to represent something much sought after that may not even exist, or, at least, may not ever be found. Such use is evident in Edgar Allan Poe's poem "El Dorado." In this context, El Dorado bears similarity to other myths such as the Fountain of Youth and Shangri-la. The other side of the ideal quest metaphor may be represented by Helldorado, a satirical nickname given to Tombstone, Arizona (United States) in the 1880s by a disgruntled miner who complained that many of his profession had traveled far to find El Dorado, only to wind up washing dishes in restaurants. The South African city Johannesburg is commonly interpreted as a modern-day El Dorado, due to the extremely large gold deposit found along the Witwatersrand on which it is situated.

Early search for gold in northern South America

Spanish conquistadores had noticed the native people's fine artifacts of gold and silver long before any legend of "golden men" or "lost cities" had appeared. The prevalence of such valuable artifacts, and the natives' apparent ignorance of their value, inspired speculation as to a plentiful source for them.

Prior to the time of the Spanish conquest of the Muisca and discovery of Lake Guatavita, a handful of expeditions had set out to explore the lowlands to the east of the Andes in search of gold, cinnamon, precious stones, and anything else of value. During the Klein-Venedig period in Venezuela (1528–1546), agents of the German Welser banking family (which had received a concession from Charles I of Spain) launched repeated expeditions into the interior of the country in search of gold, starting with Ambrosius Ehinger's first expedition in July 1529.

Spanish explorer Diego de Ordaz, then governor of the eastern part of Venezuela known as Paria (named after Paria Peninsula), was the first European to explore the Orinoco river in 1531–32 in search of gold. A veteran of Hernán Cortés's campaign in Mexico, Ordaz followed the Orinoco beyond the mouth of the Meta River but was blocked by the rapids at Atures. After his return he died, possibly poisoned, on a voyage back to Spain.[8] After the death of Ordaz while returning from his expedition, the Crown appointed a new Governor of Paria, Jerónimo de Ortal, who diligently explored the interior along the Meta River between 1532 and 1537. In 1535, he ordered captain Alonso de Herrera to move inland by the waters of the Uyapari River (today the town of Barrancas del Orinoco). Herrera, who had accompanied Ordaz three years before, explored the Meta River but was killed by the indigenous Achagua near its banks, while waiting out the winter rains in Casanare.

The search for El Dorado

Even before the conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires and the Muisca Confederation the Spanish collected vague hearsay about these polities and their riches.[9] After the Inca Empire in Peru was conquered by Francisco Pizarro and its riches proved real, new rumours of riches reached the Spanish.[10]

The earliest reference to an El Dorado-like kingdom occurred in 1531 during Ordaz's expedition when he was told of a kingdom called Meta that was said to exist beyond a mountain on the left bank of the Orinoco River. Meta was supposedly abundant in gold and ruled by a chief that only had one intact eye.[11]

Between 1531 and 1538, the German conquistadors Nikolaus Federmann and Georg von Speyer searched the Venezuelan lowlands, Colombian plateaus, Orinoco Basin and Llanos Orientales for El Dorado.[12] Subsequently, Philipp von Hutten accompanied Von Speyer on a journey (1536–38) in which they reached the headwaters of the Rio Japura, near the equator. In 1541 Hutten led an exploring party of about 150 men, mostly horsemen, from Coro on the coast of Venezuela in search of the Golden City. After several years of wandering, harassed by the natives and weakened by hunger and fever, he crossed the Rio Bermejo, and went on with a small group of around 40 men on horseback into Los Llanos, where they engaged in battle with a large number of Omaguas and Hutten was severely wounded. He led those of his followers who survived back to Coro in 1546.[13] On Hutten's return, he and a traveling companion, Bartholomeus VI. Welser, were executed in El Tocuyo by the Spanish authorities.

In 1535, Sebastian de Benalcazar, a lieutenant of Francisco Pizarro, interrogated an Indian that had been captured at Quito. Luis Daza recorded that the Indian was a warrior while Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas wrote that the Indian was an ambassador who had come to request military assistance from the Inca, unaware that they had already been conquered. The Indian told Benalcazar that he was from a kingdom of riches known as Cundinamarca far to the north where a zipa, or chief, covered himself in gold dust during ceremonies.[14] Benalcazar set out to find the chief, reportedly saying "Lets go find that golden Indian!" (Spanish: ¡Vámos a buscar a este indio dorado!),[15] eventually the chief became known to the Spaniards as El Dorado.[16] Benalcazar failed however to find El Dorado and eventually joined up with Federmann and Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada and returned to Spain.[16] It has been speculated that the land of wealth spoken of by the Indian was Arma, a kingdom whose inhabitants wore gold ornaments, which was eventually conquered by Pedro Cieza de Leon.[17]

In 1536 Gonzalo Díaz de Pineda led an expedition to the lowlands to the east of Quito and found cinnamon trees but no rich empire.

Quesada brothers' expeditions

In 1536, stories of El Dorado drew the Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada and his army of 800 men away from their mission to find an overland route to Peru and up into the Andean homeland of the Muisca for the first time. The southern Muisca settlements and their treasures quickly fell to the conquistadors in 1537 and 1538. On the Bogotá savanna, Quesada received reports from captured natives about a kingdom called Metza whose inhabitants built a temple dedicated to the sun and "keep in it an infinite quantity of gold and jewels, and live in stone houses, go about dressed and booted, and fight with lances and maces". Quesada believed this might have been El Dorado and decided to postpone his return to Santa Marta and continue his expedition for another year.[18] After his brother Gonzalo had left for Spain in May 1539, Spanish conquistador Hernán Pérez de Quesada set out a new expedition in September 1540, leaving with 270 Spanish soldiers and countless indigenous porters to explore the Llanos Orientales. One of his main captains on this journey was Baltasar Maldonado. Their expedition was unsuccessful and after reaching Quito, the troops returned to Santafe de Bogotá.[8]

Pizarro and Orellana's discovery of the Amazon

In December of 1540, Gonzalo Pizarro, the younger half-brother of Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish conquistador who toppled the Incan Empire in Peru, as vice governor of the province of Quito (current Ecuador), prepared in Cusco an expedition of 170 spaniards and 3,000 natives and departed to Quito to explore lands far to the east, where many natives talked of the existence of a valley rich in both cinnamon and gold. When he arrived in Quito he banded together 220 soldiers and about 4,000 natives, and departed in February 1541. He led them eastward down the Rio Coca and Rio Napo. Francisco de Orellana, a relative of Pizarro, accompanied him on the expedition as his second in command. Gonzalo quit after many of the soldiers and natives had died from hunger, disease, and periodic attacks by hostile natives. He ordered Orellana to continue downstream, where he eventually made it to the Atlantic Ocean. The expedition found neither cinnamon nor gold, but Orellana is credited with discovering the Amazon River (so named because of a tribe of female warriors that attacked Orellana's men while on their voyage).

Expeditions of Pedro de Ursúa and Lope de Aguirre

In 1560, Basque conquistadors Pedro de Ursúa and Lope de Aguirre journeyed down the Marañón and Amazon Rivers, in search of El Dorado, with 300 Spaniards and hundreds of natives;[19] the actual goal of Ursúa was to send idle veterans from the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire away, to keep them from trouble-making, using the El Dorado myth as a lure. A year later, Aguirre participated in the overthrow and killing of Ursúa and his successor, Fernando de Guzmán, whom he ultimately succeeded.[20][21] He and his men reached the Atlantic (probably by the Orinoco River), destroying native villages of Margarita island and actual Venezuela.[22] In 1561 Aguirre's expedition ended with his death in Barquisimeto, and in the years since then he has been treated by historians as a symbol of cruelty and treachery in the early history of colonial Spanish America.

Lake Guatavita gold

While the existence of a sacred lake in the Eastern Ranges of the Andes, associated with Indian rituals involving gold, was known to the Spaniards possibly as early as 1531, its location was only discovered in 1537 by conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada while on an expedition to the highlands of the Eastern Ranges of the Andes in search of gold.[23]

Conquistadores Lázaro Fonte and Hernán Perez de Quesada attempted (unsuccessfully) to drain the lake in 1545 using a "bucket chain" of labourers. After 3 months, the water level had been reduced by 3 metres, and only a small amount of gold was recovered, with a value of 3000–4000 pesos (approx. US$100,000 today; a peso or piece of eight of the 15th century weighs 0.88 oz of 93% pure silver).

A later more industrious attempt was made in 1580, by Bogotá business entrepreneur Antonio de Sepúlveda. A notch was cut deep into the rim of the lake, which managed to reduce the water level by 20 metres, before collapsing and killing many of the labourers. A share of the findings—consisting of various golden ornaments, jewellery and armour—was sent to King Philip II of Spain. Sepúlveda's discovery came to approximately 12,000 pesos. He died a poor man, and is buried at the church in the small town of Guatavita.

In 1801, Alexander von Humboldt made a visit to Guatavita, and on his return to Paris, calculated from the findings of Sepúlveda's efforts that Guatavita could offer up as much as $300 million worth of gold.[1]

In 1898, the Company for the Exploitation of the Lagoon of Guatavita was formed and taken over by Contractors Ltd. of London, in a deal brokered by British expatriate Hartley Knowles. The lake was drained by a tunnel that emerged in the centre of the lake. The water was drained to a depth of about 4 feet of mud and slime. This made it impossible to explore, and when the mud had dried in the sun, it had set like concrete. Artifacts worth only about £500 were found, and auctioned at Sotheby's of London. Some of these were donated to the British Museum.[24] The company filed for bankruptcy and ceased activities in 1929.

In 1965, the Colombian government designated the lake as a protected area. Private salvage operations, including attempts to drain the lake, are now illegal.

Antonio de Berrio's expeditions

The Spanish Governor of Trinidad, Antonio de Berrio (nephew of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada), made three failed expeditions to look for El Dorado. Between 1583 and 1589 he carried out his first two expeditions, going through the wild regions of the Colombian plains and the Upper Orinoco. In 1590 he began his third expedition, ascending the Orinoco to reach the Caroní River with his own expeditionaries and another 470 men under command of Domingo de Vera.[25] In March 1591, while he was waiting for supplies on Margarita Island, his entire force was taken captive by Walter Raleigh, who proceeded up the Orinoco in search of El Dorado, with Berrio as a guide. Berrio took them to the territories he had previously explored by himself years before. After several months Raleigh's expedition returned to Trinidad, and he released Berrio at the end of June 1595 on the coast of Cumaná in exchange for some English prisoners.[26] His son Fernando de Berrío y Oruña (1577–1622) also made numerous expeditions in search of El Dorado.

Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh's 1595 journey with Antonio de Berrio had aimed to reach Lake Parime in the highlands of Guyana (the supposed location of El Dorado at the time). He was encouraged by the account of Juan Martinez, believed to be Juan Martin de Albujar, who had taken part in Pedro de Silva's expedition of the area in 1570, only to fall into the hands of the Caribs of the Lower Orinoco. Martinez claimed that he was taken to the golden city in blindfold, was entertained by the natives, and then left the city and couldn't remember how to return.[27] Raleigh had set many goals for his expedition, and believed he had a genuine chance at finding the so-called city of gold. First, he wanted to find the mythical city of El Dorado, which he suspected to be an actual Indian city named Manõa. Second, he hoped to establish an English presence in the Southern Hemisphere that could compete with that of the Spanish. His third goal was to create an English settlement in the land called Guyana, and to try to reduce commerce between the natives and Spaniards.

In 1596 Raleigh sent his lieutenant, Lawrence Kemys, back to Guyana in the area of the Orinoco River, to gather more information about the lake and the golden city.[28] During his exploration of the coast between the Amazon and the Orinoco, Kemys mapped the location of Amerindian tribes and prepared geographical, geological and botanical reports of the country. Kemys described the coast of Guiana in detail in his Relation of the Second Voyage to Guiana (1596)[29] and wrote that indigenous people of Guiana traveled inland by canoe and land passages towards a large body of water on the shores of which he supposed was located Manoa, Golden City of El Dorado.

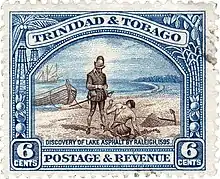

Though Raleigh never found El Dorado, he was convinced that there was some fantastic city whose riches could be discovered. Finding gold on the riverbanks and in villages only strengthened his resolve.[30] In 1617, he returned to the New World on a second expedition, this time with Kemys and his son, Watt Raleigh, to continue his quest for El Dorado. However, Raleigh, by now an old man, stayed behind in a camp on the island of Trinidad. Watt Raleigh was killed in a battle with Spaniards and Kemys subsequently committed suicide.[29] Upon Raleigh's return to England, King James ordered him to be beheaded for disobeying orders to avoid conflict with the Spanish.[31] He was executed in 1618.

Post-Elizabethan expeditions

On 23 March 1609, Robert Harcourt accompanied by his brother Michael and a company of adventurers, sailed for Guiana. On 11 May he arrived at the Oyapock River. Local people came on board, and were disappointed at the absence of Sir Walter Raleigh after he had famously visited during his exploration of the area in 1595. Harcourt gave them aqua vitae. He took possession in the king's name of a tract of land lying between the River Amazon and River Essequibo on 14 August, left his brother and most of his company to colonise it, and four days later embarked for England.[32]

In early 1611 Sir Thomas Roe, on a mission to the West Indies for Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, sailed his 200-ton ship, the Lion's Claw, some 320 kilometres (200 mi) up the Amazon,[33] then took a party of canoes up the Waipoco (probably the Oyapock River) in search of Lake Parime, negotiating thirty-two rapids and traveling about 160 km (100 mi) before they ran out of food and had to turn back.[34][35][36][37]

In 1627 North and Harcourt, obtained letters patent under the great seal from Charles I, authorising them to form a company for "the Plantation of Guiana", North being named as deputy governor of the settlement. Short of funds, this expedition was fitted out, a plantation established in 1627, and trade opened by North's endeavours.[32]

In 1637–38, two monks, Acana and Fritz, undertook several journeys to the lands of the Manoas, indigenous peoples living in western Guyana and what is now Roraima in northeastern Brazil. Although they found no evidence of El Dorado, their published accounts were intended to inspire further exploration.[38]

In November 1739, Nicholas Horstman, a German surgeon commissioned by the Dutch Governor of Guiana, traveled up the Essequibo River accompanied by two Dutch soldiers and four Indian guides. In April 1741 one of the Indian guides returned reporting that in 1740 Horstman had crossed over to the Rio Branco and descended it to its confluence with the Rio Negro. Horstman discovered Lake Amucu on the North Rupununi but found neither gold nor any evidence of a city.[39]

In 1740, Don Manuel Centurion, Governor of Santo Tomé de Guayana de Angostura del Orinoco in Venezuela, hearing a report from an Indian about Lake Parima, embarked on a journey up the Caura River and the Paragua River, causing the deaths of several hundred persons. His survey of the local geography, however, provided the basis for other expeditions starting in 1775.[1]

From 1775 to 1780, Nicholas Rodriguez and Antonio Santos, two entrepreneurs employed by the Spanish Governors, set out on foot and Santos, proceeding by the Caroní River, the Paragua River, and the Pacaraima Mountains, reached the Uraricoera River and Rio Branco, but found nothing.[40]

Between 1799 and 1804, Alexander von Humboldt conducted an extensive and scientific survey of the Guyana river basins and lakes, concluding that a seasonally-flooded confluence of rivers may be what inspired the notion of a mythical Lake Parime, and of the supposed golden city on the shore, nothing was found.[1] Further exploration by Charles Waterton (1812)[41] and Robert Schomburgk (1840)[42] confirmed Humboldt's findings.

Gold strikes and the extractive wealth of the rainforest

It appears today that the Muisca obtained their gold in trade, and while they possessed large quantities of it over time, no great store of the metal was ever accumulated.

By the mid-1570s, the Spanish silver strike at Potosí in Upper Peru (modern Bolivia) was producing unprecedented real wealth.

In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I of England died, bringing to an end the era of Elizabethan adventurism. In 1618, Sir Walter Raleigh, the great inspirer, was beheaded after returning from an expedition to Venezuela in search of El Dorado for an attack on a Spanish outpost.

In 1695, bandeirantes in the south struck gold along a tributary of the São Francisco River in the highlands of State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The prospect of real gold overshadowed the illusory promise of "gold men" and "lost cities" in the vast interior of the north.

The gold mine at El Callao (Venezuela), started in 1871, a few miles at south of Orinoco River, was for a time one of the richest in the world, and the goldfields as a whole saw over a million ounces exported between 1860 and 1883. The immigrants who emigrated to the gold mines of Venezuela were mostly from the British Isles and the British West Indies.

The Orinoco Mining Arc (OMA),[43] officially created on February 24, 2016 as the Arco Mining Orinoco National Strategic Development Zone, is an area rich in mineral resources that the Republic of Venezuela has been operating since 2017;[44][45] occupies mostly the north of the Bolivar state and to a lesser extent the northeast of the Amazonas state and part of the Delta Amacuro state. It has 7,000 tons of reserves of gold, copper, diamond, coltan, iron, bauxite and other minerals.

A photograph taken from the International Space Station (ISS) in 2021 showed golden areas near the Amazon River. These were determined to be extensive illegal gold mining operations.[46] Such photography and, especially, satellite surveys, have revealed the extent of the impact of these operations. They suggest the rate of forest loss more than tripled as gold prices rose in 2008, largely driven by small, illegal mining operations that now account for most activity in the region.[47] A team from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Stanford, California, has estimated, using satellite data and field surveys together, that mining covered fewer than 10,000 hectares in 1999 but had spread beyond 50,000 hectares by September 2012.[48]

Recent research

In 1987–1988, an expedition led by John Hemming of the Royal Geographical Society failed to uncover any evidence of the ancient city of Manoa on the island of Maracá in north-central Roraima. Members of the expedition were accused of looting historic artifacts[49] but an official report of the expedition described it as "an ecological survey."[50]

Evidence for the existence of Lake Parime

Although it was dismissed in the 19th century as a myth, some evidence for the existence of a lake in northern Brazil has been uncovered. In 1977 Brazilian geologists Gert Woeltje and Frederico Guimarães Cruz along with Roland Stevenson,[51] found that on all the surrounding hillsides a horizontal line appears at a uniform level approximately 120 metres (390 ft) above sea level.[52] This line registers the water level of an extinct lake which existed until relatively recent times. Researchers who studied it found that the lake's previous diameter measured 400 kilometres (250 mi) and its area was about 80,000 square kilometres (31,000 sq mi). About 700 years ago this giant lake began to drain due to tectonic movement. In June 1690, a massive earthquake opened a bedrock fault, forming a rift or a graben that permitted the water to flow into the Rio Branco.[53] By the early 19th century it had dried up completely.[54]

Roraima's well-known Pedra Pintada is the site of numerous pictographs dating to the pre-Columbian era. Designs on the sheer exterior face of the rock were most likely painted by people standing in canoes on the surface of the now-vanished lake.[55] Gold, which was reported to be washed up on the shores of the lake, was most likely carried by streams and rivers out of the mountains where it can be found today.[56]

21st-Century Explorations

Since 2007 a team of international and multidisciplinary researchers, led by Venezuelan archaeologist and explorer Jose Miguel Perez-Gomez, has conducted several expeditions into southeast Venezuela’s unexplored jungle areas in search of storied Lake Parime. The team presented its results in October 2019 at the TerraSAR-X / TanDEM-X Science Team Meeting held at the DLR’s (Deutschen Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt’s, i.e., the German Aerospace Center) Microwave and Radar Institute in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany (1). These results derived from a large amount of data collected from multiple expeditions. They were based on analysis of historical sources; indigenous oral traditions; archaeological and geological studies; digital elevation models (DEM); and aerial, along with satellite, remote sensing surveys obtained from NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Missions (SRTM), the Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) instrument, and TanDEM-X synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensors from the DLR’s Microwave and Radar Institute in Germany. By using these advanced remote sensing technologies, the researchers were able to reconstruct a fossil lake and also identify the place where it emptied. Based on a GIS flood projection model, the flooding computations for the proposed lake area revealed a body of water much longer than it was wide. In fact, an elongated rift lake emerged, markedly similar to Sir Walter Raleigh’s original map of 1595.[57]

El Dorado in popular culture

Music

- Eldorado, by Neil Young (1989)

- "El Dorado" by Ravi (2020)

- El Dorado, by The Jayhawks (2018)

- El Dorado, album by Shakira (2017)

- El Dorado World Tour, concert tour by Shakira (2018)

- El Dorado, by Marillion (2016)

- El Dorado, by Exo (group) (2015) album "EXODUS"

- ElDorado, a Japanese Visual Kei band

- El Dorado, by Death Cab for Cutie (2015)

- El Dorado, by Every Time I Die (2014)

- El Dorado, by Two Steps From Hell (2012)

- El Dorado, by Iron Maiden (2010)

- Eldorado, by Dave Rodgers (2007)

- El Dorado, by Aterciopelados (1995)

- Eldorado, by The Tragically Hip (1992)

- El Dorado, by John Adams (1991)

- Eldorado, by Komu Vnyz (1990)

- Eldorado, by Patrick O'Hearn (1989)

- El Dorado, by Prince Daddy & The Hyena (2022)

- El Dorado, by Restless Heart (1988)

- El Dorado, by Seikima-II (1986)

- El Dorado, by the March Violets (1986)

- El Dorado, by Agent Orange (band) (1981)

- Eldorado, by Goombay Dance Band (1980)

- Eldorado, album by Electric Light Orchestra (1974)

- Eldorado, by Sopor Aeternus & the Ensemble of Shadows (2000)

- Curse of Eldorado, album by Ghoultown (2020)

- El Dorado, by Stellar (Sid Banerjee) (2021)[58]

- El Dorado by 24kGoldn (2021)

- Eldorado by Sanah (singer) (2022)

- El Dorado by Dirty Heads (2022)

- Eldorado by Edu Falaschi (2023)

- El Dorado by Zach Bryan (2023)

Pinball

- El Dorado City of Gold (pinball) (1984)

- Zen Studios' El Dorado (2009)

Video games

- Monster Hunter: World (2018)

- Civilization VI (2017)

- Europa Universalis IV – El Dorado DLC (2015)

- Age of Empires II: The Forgotten HD (2013)

- Pirate101 (2012)

- The Secret World (2012)

- Sid Meier's Civilization V (2010)

- Uncharted: Drake's Fortune (2007)[59][60]

- Pitfall: The Lost Expedition (2004)

- The Journeyman Project 3: Legacy of Time (1998)

- Sid Meier's Colonization (1994)

- Inca (1992)

- Gold and Glory: The Road to El Dorado (2000)

Mobile Games

- Monster Strike (2013)

Tabletop (Board) Games

- The Quest for El Dorado (2017)

Movies

- Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972)

- El Dorado (1966)

- El Dorado (1988)

- The Mask of Zorro (1998)

- The Road to El Dorado (2000)

- National Treasure: Book of Secrets (2007)

- Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

- El Dorado Temple of the Sun (2010)

- Entranced Earth (1967)

- The Lost City of Z (2016)

- Amazon Obhijaan (2017)

- Gold (2017)

- K.G.F: Chapter 1 (2018)

- K.G.F: Chapter 2 (2022)

- Professor Shonku O El Dorado (2019)

- Dora and the Lost City of Gold (2019)

Television

- The Mysterious Cities of Gold (1982–83, 2012–16)

- James Bond Jr (1991, Earth Cracker episode)

- Eldorado (1992–93)

- Outer Banks (2023, Season 3)

- History's Greatest Mysteries The Search for Eldorado (2023)

Anime

- Garo: Vanishing Line (2017–18)

- One Piece (Volume 30–39)

Comics

- The Gilded Man (comics) (1952 Donald Duck's story by Carl Barks based on the legend)

- Beyond the Windy Isles, album of Corto Maltese's adventures by Hugo Pratt (1970–71)

- Celtic Tales, album of Corto Maltese's adventures by Hugo Pratt (1971–72)

- The Last Lord of Eldorado (1998 Donald Duck's story by Don Rosa)

Poems

- "Eldorado" (1849)

Literature

- El Camino de El Dorado novel of Arturo Uslar Pietri published in 1947

- Candide satire of Voltaire published in 1759 describes a place called El Dorado, a geographically isolated utopia where the streets are covered with precious stones, there exist no priests, and all of the king's jokes are funny.

- The Language of Eldorado by Mark McWatt

- The ending of A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh describes the book's protagonist, Tony Last, in search of a mythical city in the Amazon rainforest.

- The Loss of El Dorado, written by Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul, published in 1969

Cars

See also

- Sanaleipak

- Darkness in El Dorado

- Kalakeyas

- La Canela, the "Valley of Cinnamon," a legendary location in South America that grew out of expectations aroused by the voyage of Columbus

- Lake Parime

- Liborio Zerda

- List of mythological places

- Lost City of Z

- Montezuma's treasure, a somewhat similar Mexican/southwestern American legend

- The Narrative of Robert Adams (1816), which dispelled a then-prevalent European misconception that Timbuktu was an African El Dorado

- Paititi

- Seven Cities of Gold, mythological locations in New Mexico, United States (some accounts call El Dorado one of the seven)

- Spanish conquest of the Muisca, the main expedition in the quest for El Dorado

- Tripura (mythology)

- Witwatersrand Gold Rush

Notes

- Spanish original:

Era costumbre entre estos naturales que el que había de ser sucesor y heredero del señorío o cacicazgo de su tío, a quien heredaba, había de ayunar seis años metido en una cueva que tenían dedicada y señalada par esto, y que en todo este tiempo no había de tener parte con mujeres, ni comer carne, sal ni ají y otras cosas que les vedaban; y entre ellas que durante el ayuno no habían de ver el sol, sólo de noche tenían licencia para salir de la cueva y ver la luna y estrellas y recogerse antes que el sol los viese. Y cumplido este ayuno y ceremonias se metían en posesión del cacicazgo o señorío, y la primera jornada que habían de hacer era ir a la gran laguna de Guatavita a ofrecer y sacrificar al demonio (sic) que tenían por su dios y señor. La ceremonia que en esto había era que en aquella laguna se hacía una gran balsa de juncos, aderezábanla y adornábanla todo lo más vistoso que podían be, metían en ella cuatro braseros encendidos en que desde luego quemaban mucho moque, que es el sahumerio de estos naturales, y trementina, con otros muchos y diversos perfumes. Estaba a este tiempo toda la laguna en redondo, con ser muy grande, y hondable de tal manera que puede navegar en ella un navío de alto bordo, la cual estaba toda coronada de infinidad de indios e indias, con mucha plumería, chagualas y coronas de oro, con infinitos fuegos a la redonda; y luego que en la balsa comenzaba el sahumerio lo encendían en tierra, en tal manera, que el humo impedía la luz del día.

A este tiempo desnudaban al heredero en carnes vivas y lo untaban con una tierra pegajosa y lo espolvoreaban con oro en polvo y molido, de tal manera que iba cubierto todo de este metal. Metíanle en la balsa, en la cual iba parado, y a los pies le ponían un gran montón de oro y esmeraldas para que ofreciese a su dios. Entraban con él en la balsa cuatro caciques, los más principales, sus sujetos, muy aderezados de plumería, coronas de oro, brazales y chagualas y orejeras de oro, también desnudos, y cada cual llevaba su ofrecimiento. En partiendo la balsa de tierra comenzaban los instrumentos, cornetas, fotutos y otros instrumentos, y con esto una gran vocería que atronaba montes y valles y duraba hasta que la balsa llegaba al medio de la laguna, de donde, con una bandera, se hacía señal para el silencio.

Hacía el indio dorado su ofrecimiento echando todo el oro que llevaba a los pies en el medio de la laguna, y los demás caciques que iban con él y le acompañaban hacían lo propio, lo cual acabado abatían la bandera, que en todo el tiempo que gastaban en el ofrecimiento la tenían levantada, y partiendo la balsa a tierra comenzaba la grita, gaitas y fotutos con muy largos corros de bailes y danzas a su modo, con la cual ceremonia recibían al nuevo electo y quedaba conocido por señor y príncipe.

De esta ceremonia se tomó aquel nombre tan celebrado del Dorado, que tantas vidas ha costado.[4]

References

- "Humboldt, Alexander von, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America During the Years 1799–1804, (chapter 24). Henry G. Bohn, London, 1853". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- Ocampo López, Javier (2007). Grandes culturas indígenas de América [Great indigenous cultures of the Americas] (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A. pp. 1–238. ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

- (in Spanish) Chiminichagua, o el ser supremo

- Freyle, Juan Rodríguez (1636). Conquista y descubrimiento del Nuevo Reino de Granada [El Carnero].

- Castellanos, Juan de (1850). "Parte III, Canto II". Elejias de Varones Ilustres de Indias. Madrid.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo (1851) [1535]. José Amador de los Ríos (ed.). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana (1596; repr., Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1968)

- John Hemming, Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians, 1500–1760, Harvard University Press, 1978. ISBN 0674751078

- de Gandía 1929, p. 106.

- de Gandía 1929, p. 110.

- Hemming 1978, p. 15.

- Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Spire, Georg von". in Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- "Hutten, Philipp (Felipe Dutre, de Utre, de Ure), Conquistador, 1511 – 24.4.1546 in Venezuela." Deutsche Biographie

- John Hemming, The search for El Dorado pp. 101–102.

- de Gandía 1929, p. 113.

- Hemming 1978, pp. 91–95.

- Hemming 1978, p. 85.

- Hemming 1978, p. 91.

- Beatriz Pastor; Sergio Callau (2011). Lope de Aguirre y la rebelión de los marañones. Parkstone International. pp. 1524–1525. ISBN 978-84-9740-535-5.

- William A. Douglass; Jon Bilbao (2005). Amerikanuak: Basques in the New World. University of Nevada Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-87417-625-4.

- Elena Mampel González; Neus Escandell Tur (1981). Lope de Aguirre: Crónicas, 1559-1561. Edicions Universitat Barcelona. p. 132. ISBN 978-84-85411-51-1.

- Gabriel Sánchez Sorondo (2010). Historia oculta de la conquista de América. Ediciones Nowtilus S.L. p. 124. ISBN 978-84-9763-601-8.

- Hemming, John. "The Draining of Lake Guatavita" (PDF). SA Explorers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Guatavita, Lake". British Museum Collection. Trustees of the British Museum. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Bell, Robert (1837). Lives of the British Admirals: Robert Devereux. Sir Walter Raleigh Volume 4. Longman. pp. 330–335.

- Sir Walter Ralegh's Discoverie of Guiana, Hakluyt Society, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006. ISBN 0904180875

- Dotson, Eliane. "Lake Parime and the Golden City" (PDF). Wash Map Society. p. 4. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Raleigh's Second Expedition to Guiana". Guyana. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Laughton, John Knox (1885–1900). "Kemys, Lawrence (DNB00)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30.

- "Sir Walter Raleigh". Learn NC. UNC School of Education. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Drye, Willie. "El Dorado Legend Snared Sir Walter Raleigh". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- From Robert Harcourt (explorer): Goodwin, Gordon (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 24. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Cardoso, Alírio (2011). "A conquista do Maranhão e as disputas atlânticas na geopolítica da União Ibérica (1596–1626)". Revista Brasileira de História. 31 (61): 317–338. doi:10.1590/S0102-01882011000100016.

- Dean, James Seay (2013). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752496689.

- Williamson, James Alexander (1923). English colonies in Guiana and on the Amazon, 1604–1668. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 54.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1885–1900). "Roe, Thomas (DNB00)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49.

- Brown, Michael J. (2015). Rowse, A. L. (ed.). Itinerant Ambassador: The Life of Sir Thomas Roe. University Press of Kentucky. p. 15. ISBN 978-0813162270. JSTOR j.ctt130j7sv.

- Durivage, Francis Alexander (1847). A popular cyclopedia of history: ancient and modern, forming a copious historical dictionary of celebrated institutions, persons, places and things ... Case, Tiffany and Burnham. p. 717.

- Harris, C. A.; Abraham, John; De Villiers, Jacob (1911). Storm Van's Gravesande: The Rise of British Guiana, Compiled from his Works. Hakluyt Society.

- Pierce, Edward M. (1867). The Cottage Cyclopedia of History and Biography: A Copious Dictionary of Memorable Persons, Events, Places and Things, with Notices of the Present State of the Principal Countries and Nations of the Known World, and a Chronological View of American History. Case, Lockwood. p. 1004.

- Waterton, Charles (1891). Moore, Norman (ed.). Wanderings in South America. London, Paris & Melbourne: Cassell & Co, Ltd. p. 192 – via gutenberg.org.

- Rivière, Peter (2006). The Guiana Travels of Robert Schomburgk, 1835–1844: Explorations on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society, 1835–1839. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 274. ISBN 0904180867.

- "Arco Minero del Orinoco: Decreto N° 2.248, mediante el cual se crea la Zona de Desarrollo Estratégico Nacional" (PDF). Gaceta Oficial de la Republica Bolivarinara de Venezuela. Vol. 40, no. 855. March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2021.

- Egaña, Carlos, 2016. El Arco Minero del Orinoco: ambiente, rentismo y violencia al sur de Venezuela

- Cano Franquiz, María Laura. "Arco Minero del Orinoco vulnera fuentes vitales y diversidad cultural en Venezuela". La Izquierda Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "NASA's stunning photo showing 'Gold Rivers' in Peruvian Amazon has a grim backstory". www.timesnownews.com. 14 February 2021. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- "Illicit gold rush in Peruvian Amazon". Nature. 502 (7473): 596. October 2013. doi:10.1038/502596b. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Asner, G. P.; Llactayo, W.; Tupayachi, R.; Luna, E. R. (12 November 2013). "Elevated rates of gold mining in the Amazon revealed through high-resolution monitoring". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (46): 18454–18459. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11018454A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1318271110. PMC 3832012. PMID 24167281.

- Videla, Rafael (1 January 2008). "El Dorado: El Gran Descubrimiento de Roland Stevenson". Alerta Austral (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Hemming, John; Bowles, Steve; Watson, Fiona (1988). "Maracá Rainforest Project Brazil 1987-1988" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Stevenson, Roland. "Parime: Finding the Legendary Lake". Netium. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Maziero, Dalton Delfini. "El Dorado Em busca dos antigos mistérios Amazônicos". Arqueologiamericana (in Portuguese). Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Veloso, Alberto V. (September 2014). "On the footprints of a major Brazilian Amazon earthquake". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 86 (3): 1115–1129. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420130340.

- Shea, Jeff (March 2013). "The March 2013 Paragua River Expedition: Penetration into The Meseta de Ichún of Venezuela" (PDF). Explorers Club Report #60. p. 110. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Fonseca, J. A. (7 September 2011). "A Misteriosa Pedra Pintada (Roraima)". Moiseslime (in Portuguese). WordPress. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Significant gold deposits in Roraima Basin – study". Stabroek News. March 22, 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Perez-Gomez et al 2019. "Remote Sensing Archaeology: Searching for Lake Parima from Space." TerraSAR-X/ TanDEM-X Science Team Meeting, German Aerospace Center (DLR). Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany.

- Ashton, Kimberly (17 December 2020). "'It Is Wildfire': Berklee Alum on How TikTok Is Reshaping the Industry". www.berklee.edu. Berklee. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- "The Search for El Dorado". IGN. Ziff Davis, LLC. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "Gold and Bones". IGN. Ziff Davis, LLC. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

Bibliography

- de Gandía, Enrique (1929). "Capítulo VII: El Dorado". Historia crítica de los mitos de la conquista americana (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Juan Roldán y Cía.

- Hemming, John (1978). The Search for El Dorado. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 9780718117542.

Further reading

- Hemming, John (1978). Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians, 1500–1760. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674751078. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Bandelier, A. F. A. (1893). The Gilded Man, El Dorado. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rodriguez Freyle, Juan (1859). El Carnero: Conquista y descubrimiento del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacuch. ISBN 84-660-0025-9.

- Hagen, Victor Wolfgang von (1968). The Gold of El Dorado: The Quest for the Golden Man.

- Naipaul, V.S. (1969). The Loss of El Dorado. UK: André Deutsch.

- Nicholl, Charles (1995). The Creature in the Map: A Journey to El Dorado. London. ISBN 0-09-959521-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zerda, Liborio (1947) [1883]. El Dorado (PDF). Retrieved 2017-03-23.

External links

- (in Spanish) Analysis of maps from 1570 to 1842, showing El Dorado in various locations around South America

- El Dorado raft – Gold Museum, Bogotá, Colombia

- Lost City of Z – El dorado the city of gold

- El Dorado – Ancient History Encyclopedia

- The Legend of El Dorado – Tairona Heritage Trust