Witwatersrand Gold Rush

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush was a gold rush that began in 1886 and led to the establishment of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was a part of the Mineral Revolution.

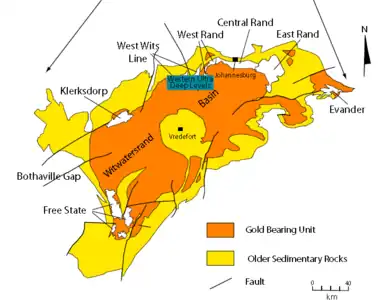

Witwatersrand Basin and major goldfields | |

| Date | 1886 |

|---|---|

| Location | Witwatersrand Basin, Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Outcome | The largest gold rush ever led to the eventual Boer defeat in the Second Boer War (1899-1902), the loss of Boer autonomy and self-government, and total British rule in South Africa |

| History of South Africa |

|---|

| Timeline |

| List of years in South Africa |

|

|

Origins

In the modern-day province of Mpumalanga, gold miners in the alluvial mines of Barberton and Pilgrim's Rest and local tribes had suspected the existence of gold deposits. In 1886, gold was found in the Witwatersrand region. Scientific studies show that the "Golden Arc", which stretches from Johannesburg to Welkom, used to be a massive inland lake, and silt and gold deposits from alluvial gold settled in the area that formed the found gold.

Discovery

The first discovery of gold in the region was made in 1852 on the Pardekraal farm, Krugersdorp, in the South African Republic (ZAR) by John Henry Davis, a Welsh mineralogist.[1][2]: 11 Davis presented his gold find to President Andries Pretorius but feared what would happen to the new republic if the discovery became widely known. Davis was told to sell the gold, worth £600, to the Transvaal Treasury and was subsequently ordered to leave the country and escorted to the border, where he returned to the Cape Colony.[2]: 11 [3]: 49

Another find by Pieter Jacob Marais, who had dug gold in California, was recorded in 1853 on the Jukskei River but was subject to similar secrecy.[4][5]: 18 He arrived at Potchefstroom on September 3, 1853. Marais explored the northern slopes of the Witwatersrand, a few kilometers from the future main reef, finding small gold samples while panning the Crocodile and Jukskei rivers and exploring the Suikerboschrand in the south during October and November 1853.[2]: 12–13 On December 1, Marais sought approval from the Volksraad to look for gold, which was accepted with the provision that the Commission of the existing districts of the Republic would be notified if it was discovered.[5]: 17 He was also warned that if he told any foreign power about any potential finds that caused a disturbance to the republic's existence, he would be punished by death.[3]: 49 Marais then paddled the Sand and Dwars rivers in January 1854.[2]: 12–13 His small gold finds were exhibited at the courthouse in Potchefstroom in January 1854.[5]: 17 After submitting his final report to the ZAR government on April 7, 1855, he left the ZAR in 1855 to settle in Dordrecht, Cape Colony.[2]: 14 [5]: 18

In 1856, Lieutenant Lys travelled to Pretoria from Pietermaritzburg and became stuck crossing a marsh on the farm Driefontein, today's Germiston, which would become the Knights Mine.[3]: 16 [2]: 19 On returning to his wagon, he discovered conglomerate rock that, when crushed contained, gold.[2]: 19

Though there were smaller mining operations in the region, it wasn't until 1884 and the subsequent 1886 discovery at Langlaagte that the Witwatersrand gold rush got underway in earnest.[6]

Explorer and prospector Jan Gerrit Bantjes (1840-1914) was the first and original discoverer of a Witwatersrand gold reef in June 1884. He had prospected the area since the early 1880s,[7] and operated the Kromdraai Gold Mine in 1883 in the NW of present-day Johannesburg with his partner Johannes Stephanus Minnaar in an area known today as "The Cradle of Humankind". However, he found minor reefs, and today the consensus falsely holds that credit for the discovery of the main gold reef is attributed to George Harrison, whose findings on the farm Langlaagte were made in July 1886, either through accident or systematic prospecting. This was a British attempt to give credit for the discovery to the Anglo-Saxon sector to justify claiming the Witwatersrand fields as British. This move was one of the factors leading to the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. Harrison declared his claim with the then-government of the South African Republic (ZAR), and the area was pronounced open. His discovery was recorded with a monument where the original gold outcrop is believed to be located and a park named in his honor. Harrison is believed to have sold his claim for less than 10 pounds before leaving the area.[8]

News of gold spread rapidly and reached Cecil Rhodes in Kimberley. Rhodes and his partner Robinson, with a team of companions, were curious and rode over 400km to Bantjes' camp at Vogelstruisfontein, where they stayed with him for two nights near what would later become Roodepoort. Rhodes purchased the first batch of Witwatersrand gold from Bantjes for £3000. This purchase was the first transaction of the newly formed company, Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa.[9]

News reached the rest of the world, and prospectors from Australia to California began arriving in masses, and settlers arrived in soon-to-be Johannesburg. The entrance of foreigners was going well, but a number of years later, President Paul Kruger of the South African Republic (ZAR) worried that foreigners would outnumber the Boers and put in place measures to stop this. Kruger discussed the measures with Bantjes, whose father, Jan Gerritze Bantjes, had educated Kruger when he was a boy during the Great Trek. One of the measures placed heavy taxes on the sale of dynamite to foreigners to slow the momentum. This agitated the miners, and the British took this as a reason to claim the gold fields for themselves. The Jameson Raid followed, which brought attention to Cecil Rhodes. The Jameson Raid was supported by Rhodes and led by Sir Leander Starr Jameson. Its intent was to overthrow the Transvaal government and turn the region into a British colony. There were 500 men who took part in the uprising; 21 were killed, and many were arrested, then trialed and sentenced.[10]

Founding of Johannesburg

The mining village of Ferreira's Camp was formalized into a settlement after people seeking gold settled in the area. Initially, the ZAR did not believe that the gold would last for long and mapped out a small triangular piece of land to cram as many plots onto as possible. This is the reason Johannesburg's central business district streets are so narrow. There is a dispute as to the origin of the name Johannesburg and to whom Johannes, a common Dutch name, the city was named after. One theory is that it is named after two state surveyors who were sent to choose an area for the layout of the new town, Johann Rissik and Christiaan Johannes Joubert.[14]

Within 10 years, the town was the largest in South Africa, growing faster than Cape Town, which was more than 200 years older. The gold rush saw massive development of Johannesburg and the Witwatersrand, and the area today is the prime metropolitan area of South Africa. One consequence of the gold rush was the construction of the first railway lines in this part of Africa. As a result of the rapid development of the goldfields on the Witwatersrand in the 1880s and the demand for coal by the growing industry, a concession was granted by the ZAR government to the Netherlands-South African Railway Company (NZASM) on July 20, 1888, to construct a 25 kilometres (16 mi) railway line from Johannesburg to Boksburg. The line was opened on March 17, 1890, with the first train being hauled by a 14 Tonner locomotive. It became known as the "Randtram", even though it was a railway and not dedicated to tram traffic. This was the first working railway line in the Transvaal.[15][16][17][18]

The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand also created a super-wealthy class of miners and industrialists known as Randlords. Many Randlords built large estates and mansions on the Parktown Ridge.[19]

Second Boer War

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush had a significant role in both the failed Jameson Raid in 1895-1896 and the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899. The British mine owners orchestrated the coup of the Boer government, which controlled the Witwatersrand, triggering the Second Boer War.

Notes

- https://www.wits.ac.za/media/migration/files/EGRI%20274.pdf

- Rosenhal, Eric (1970). Gold! Gold! Gold! The Johannesburg Gold Rush. USA: Macmillan. pp. 12–13. LCCN 70-77972.

- Shorten, John R. (1970). The Johannesburg Saga. Johannesburg: John R. Shorten Pty Ltd. p. 1159.

- "History Of Gold In South Africa - In The Witwatersrand". The South Africa Guide. 2010-07-03. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Gray, James; Gray, Ethel L. (1937). Payable Gold. South Africa: Central News Agency.

- "South-African-Mines". www.miningartifacts.org. Archived from the original on 2019-12-28. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- SAHistory Archived 2022-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "THE WITWATERSRAND GOLD RUSH 1886 (Vc)". www.timewisetraveller.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-10-12. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- "Correspondence of Cecil John Rhodes (1)". www.bodley.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-07-16. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Anonymous (2011-03-21). "Jameson Raid". www.sahistory.org.za. Archived from the original on 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Melanie Yap (1996). Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa. Hong Kong University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-962-209-424-6. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- "Chinatown Precinct Plan" (PDF). City of Johannesburg. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

The oldest part of Johannesburg was first known as Ferreira's Camp and later Ferreiradorp.

- "Westgate Station Precinct Spatial Development Framework and Implementation Plan" (PDF). City of Johannesburg (Archive). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- "City of Johannesburg - How was Johannesburg named?". www.joburg.org.za. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- Holland, D.F. (1971). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways, Volume 1: 1859-1910 (1st ed.). Devon: Newton Abbott. pp. 109–112. ISBN 978-0-7153-5382-0.

- Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (October 1944). "The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter IV - The N.Z.A.S.M.". South African Railways and Harbours Magazine: 761–764.

- The South African Railways - Historical Survey (Editor George Hart, Publisher Bill Hart, Sponsored by Dorbyl Ltd, Circa 1978)

- "A South African Railway History". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- "Restoring of one of Parktown's Greatest Mansions | The Heritage Portal". theheritageportal.co.za. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

Primary sources

- Tabitha Jackson: The Boer War. London: Channel 4 Books, 1999.

External links

- South African Mines of Witwatersrand (Images)

- The Johannesburg Gold Fields, The Baldwin Project

- The Rand, West Gippsland Gazette, June 21, 1904