Engagé

The engagé system of indentured servitude existed in New France, the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the French West Indies from the 18th and 19th centuries.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Engagés in Canada

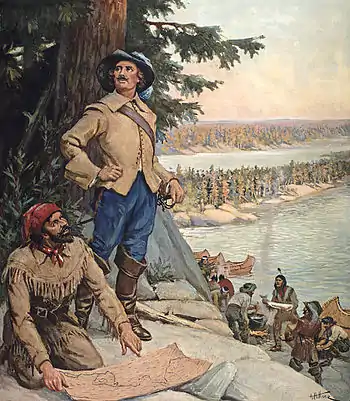

From the 18th century, an engagé (French: [ɑ̃ɡaʒe]; also spelled engagee) was a French-Canadian man employed to canoe in the fur trade as an indentured servant. He was expected to handle all transportation aspects of frontier river and lake travel: maintenance, loading and unloading, propelling, steering, portaging, camp set-up, navigation, interaction with Indigenous people, etc. The term was also applied to the men who staffed the pirogues on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Their role can be contrasted with the free, licensed voyageurs, the independent merchant coureurs des bois, as well as seafaring sailors. Engagé were people who were brought to New France by France to work there.

By the 19th century the term came to refer to employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company of any nationality.

White Indentured Servitude in Saint-Domingue

As the social systems of Saint-Domingue began eroding after the 1760s, the plantation economy of Saint-Domingue also began weakening. The price of slaves doubled between 1750 and 1780; St. Dominican land tripled in price during the same period. Sugar prices still increased, but at a much lower rate than before. The profitability of other crops like coffee collapsed in 1770, causing many planters to go into debt. The planters of Saint Domingue were eclipsed in their profits by enterprising businessmen; they no longer had a guarantee on their plantation investment, and the slave-trading economy came under increased scrutiny.[1]

Along with the establishment of a French abolitionist movement, the Société des amis des Noirs, French economists demonstrated that paid labor or indentured servitude were much more cost-effective than slave labor. In principle the widespread implementation of indentured servitude on plantations could have produced the same output as slave labor. However, the Bourbon King Louis XVI didn't want to change the labor system in his colonies, as slave labor was directly responsible for allowing France to surpass Britain in trade.[1]

Slaves, however, became expensive, each one costing around 300 Spanish dollars (some 7,333 grams (258.7 oz) of silver, valued at roughly US$5,900 with the mid-2023 price of silver - ignoring seignorage). To counteract expensive slave labor, white indentured servants were imported. White indentured servants usually worked for five to seven years and their masters provided them housing, food, and clothing.[2][3] Saint-Domingue gradually increased its reliance on indentured servants (known as petits blanchets or engagés) and by 1789 about 6 percent of all white St. Dominicans were employed as labor on plantations along with slaves.[1]

Many of the indentured servants in Saint-Domingue were German settlers or Acadian refugees deported by the British from old Acadia during the French and Indian war. Hundreds of Acadian refugees perished while forceably building a jungle military base for the French government in Saint-Domingue.[4][5]

Despite signs of economic decline, Saint-Domingue continued to produce more sugar than all of the British Caribbean islands combined.[1]

White indentured servitude in Louisiana

Louisiana had a markedly different pattern of slavery compared to other states in the American South as a result of its Louisiana Creole heritage. The scarcity of slaves made Creole planters turn to petits habitants (Creole peasants), and immigrant indentured servitude to supply manual labor; they complimented paid labor with slave labor. On many plantations, free people of color and whites toiled side-by-side with slaves. This multi-class state of affairs converted many minds to the abolition of slavery.[6]

High yields of the Creole plantations were partially obtained by better agricultural technology, but also by a more rational use of manual labor. The comparison of task completion rates between slave labor and paid labor proved that slave workers produced inferior quality work to paid employees. The maintenance of expensive slave labor then could only be justified by the social status that they conferred upon the proprietary planter.[6] The following passage is the conversation between two Creole planters on the emancipation of slaves:

-D'après ce que j'entends... on trouverait en vous, tout propriétaire d'esclaves que vous êtes, un chaud partisan de l'émancipation des noirs?

-Sans doute, répondit M.Melvil, si cette émancipation, sagement calculée, et progressivement amenée, fournit des citoyens paisibles et non des malfaiteurs de plus à nos États du Sud, si vastes que, pour les peupler, nous recevons, sans leur demander aucune exhibition de papiers, tous les fugitifs, qu'ils soient poursuivis ou condamnés par la vangeance des souverains, ou la justice des tribunaux européens.

-Mais, objecta le créole, sans esclaves que deviendraient nos plantations?

-Les affranchis les cultiveraient moyennant un salaire.

-L'expérience a démontré que les nègres libres sont les ouvriers les plus paresseux de la terre.

-Ils cesseront de l'être quand ils seront familiarisés avec la civilisation. Ils connaîtront alors de nouveaux besoins, de nouvelles jouissances. Le désir de les satisfaire leur ouvrira les yeux sur la nécessité du travail, auquel ils se livreront plus mollement peut-être à l'état de liberté qu'à celui d'esclavage, mais toujours plus efficacement que ces engagés qui nous arrivent d'Europe par cargaisons, et dont il se trouve à peine dix sur quarante capables de résister aux influences énervantes et souvent délétères de notre climat.[7]

-From what I hear... we would find in you, as much of the slave holder that you are, a strong voice for black emancipation?

-Without a doubt, responded Mr.Melvil, if this emancipation, wisely calculated, and brought about progressively, furnished peaceful citizens and not more wrong-doers to our Southern States, so vast are they that, to populate them, we receive, without asking any show of papers, all fugitives, whether they be condemned by revenge from their rulers, or from the law of European councils.

-But, objected the Creole, without slaves, what will become of our plantations?

-The affranchis (freedmen) shall farm and earn a wage.

-Past experience has shown that freed slaves are some of the laziest workers in the world.

-They shall not be any longer once they are familiarized with our civilization. They will become acquainted with new needs, and new enjoyments. The desire to satisfy them will open their eyes to the necessity of work, which perhaps shall bring them softly to the state of freedom rather than remaining in that of slavery, but more efficiently than these engagés (indentured servants) who arrive from Europe in boatloads, and of whom barely ten out of forty are capable of surviving the vexatious and often deadly influences of our climate.

Creoles often referred to engagés as "white slaves", and especially Germans were commonly sold as "white slaves" in Louisiana.[8][9][10][11][12] German engagés became known as "Redemptioners" as they would "redeem" their freedom after some years.[13]

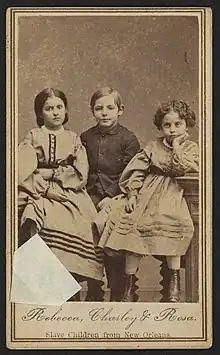

The children of engagés or petits habitants (Creole peasants) were sometimes abandoned and sold into slavery as whites slaves. One of the most famous contemporary stories of these children was that of Sally Miller, the daughter of German engagés who was sold into slavery on a sugar cane plantation.[14] The abolitionist Parker Pillsbury wrote in 1853 to his colleague William Lloyd Garrison: "A white skin is no security whatsoever. I should no more dare to send white children out to play alone, especially at night ... than I should dare send them into a forest of tigers and hyenas."[15]

The construction of the New Orleans Canal in 1831 involved almost exclusive use of indentured servitude and was one of Louisiana's deadliest public projects. As slave labor was judged too valuable to be used, most of the work was done by Irish engagés. The Irish workers died in horrific numbers, but the company tasked to complete the project had no trouble finding more men to take their place, as boatloads of poor Irish engagés continuously arrived in New Orleans.[16][9]

No official count was kept of the deaths of the engagés; most historical best guesses fall between 8,000 to 20,000 engagé deaths. Many engagés were buried without a grave marker in the levee, and for others, their bodies were simply dumped into the roadway-fill beside the canal.[16] On November 4, 1990, the Irish Cultural Society of New Orleans dedicated a large Kilkenny marble Celtic cross in New Basin Canal Park to commemorate all of the Irish workers who perished constructing the canal.

In media

Literature

- The Lost German Slave Girl (2003), the story of Sally Miller, an abandoned German girl born to engagé parents in Louisiana and sold into slavery; she lived as a slave for 25 years.

References

- Historic New Orleans Collection (2006). Common Routes: St. Domingue, Louisiana. New Orleans: The Collection. pp. 32, 33, 55, 56, 58.

- Melton McLaurin, Michael Thomason (1981). Mobile the life and times of a great Southern city (1st ed.). United States of America: Windsor Publications. p. 19.

- "Atlantic Indentured Servitude". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- Christopher Hodson (Spring 2007). ""A bondage so harsh": Acadian labor in the French Caribbean, 1763-1766". Early American Studies. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- Shane K. Bernard (2010). Cajuns and Their Acadian Ancestors: A Young Reader's History. New Orleans: Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 24.

- Carl A. Brasseaux, Glenn R. Conrad (1992). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees, 1792-1809. New Orleans: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana. pp. 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 15, 21, 22, 33, 38, 108, 109, 110, 143, 173, 174, 235, 241, 242, 243, 252, 253, 254, 268.

- Pauline Guyot Lebrun (1861). Trois mois à la Louisiane. pp. 74, 75.

- John Lowe (2008). Louisiana Culture from the Colonial Era to Katrina. LSU Press. p. 68.

- Kevin Fox Gotham, Miriam Greenberg (2014). Crisis Cities: Disaster and Redevelopment in New York and New Orleans. Oxford University Press. p. 166.

- Xavier Eyma (1861). Aventuriers et corsaires. Oxford University Press. p. 16.

- Le correspondant, Volume 195. 1899. pp. 900, 901, 902, 903.

- Emile Lefranc (1861). La Verite Sur L'Esclavage Et L'Union Aux Etats-Unis, Par Emile Lefranc. p. 60.

- H. Carter (1968). The Past as Prelude: New Orleans, 1718-1968. Pelican Publishing. p. 37.

- Bailey, Lost German Slave, p. 245. Note: Salomé Müller was noted as age four on the indenture agreement signed in 1818 in New Orleans.

- Wilson, Carol; Wilson, Calvin D. (1998). "White Slavery: An American Paradox" (PDF). Slavery and Abolition. 19 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/01440399808575226. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- Mary Helen Lagasse (7 November 2013). "A call to remember 8,000 Irish who died while building the New Orleans Canal". www.irishcentral.com. Retrieved November 8, 2022.