Slavery in Tunisia

Slavery in Tunisia was a specific manifestation of the Arab slave trade, which was abolished on 23 January 1846 by Ahmed I Bey. Tunisia was in a similar position to that of Algeria, with a geographic position which linked it with the main Trans-Saharan routes. It received caravans from Fezzan and Ghadamès, which consisted solely, in the eighteenth century, of gold powder and slaves, according to contemporary witnesses.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, slaves arrived annually in numbers ranging between 500 and 1,200. From Tunisia they were carried on to the ports of the Levant.

Origins

Tunisian slaves derived from two principal zones: Europe and a large area stretching from West Africa to Lake Chad. The kingdoms of Bornu and the region of Fezzan provided the majority of caravans. The greater part of the slaves were reduced to slavery in local wars between rival tribes or in abduction raids. Caravan routes from many Saharan centres terminated at Tunis. In addition to Ghadamès, which connected the beylik to Fezzan, Morzouk and the Kingdom of Bornou, Timbuktu was in regular contact with the Beylik via the caravan route which passed through M'zab and Djerid and put the country in touch with African groups and peoples of a large zone touching the Bambara lands, the city of Djenne and several regions of the central West Africa. The names of slaves and freedmen reported in archival documents confirm these multiple, diverse origins: beside common names like Burnaoui, Ghdamsi and Ouargli, are names indicating origin in other centres of West Africa like Jennaoui and Tombouctaoui.

European slaves, for their part, were captured in the course of razzias on the coast of the European lands, mostly Italy, France, Spain and Portugal, and from the capture of European ships. The men were used for diverse tasks (slave drivers, public works, soldiers, public servant etc.), while women were used as domestic workers and in harems. Unlike the men, it was very rare for women to be freed, although the women often converted to Islam.

Numbers

Although quantitative data does not exist for the eighteenth century, some partial censuses carried out in the middle of the nineteenth century allow some approximate conclusions about the number of slaves throughout the country. Lucette Valensi offered an estimate of around 7,000 slaves or descendants of slaves in Tunisian in the year 1861, using registers which include lists of manumissions.[1] However, such systematic records of the black population are not effective for several reasons: the abolition of slavery had occurred ten years before the first records of the subject population were taken for the mejba (a tax instituted in 1856), and therefore a good part of these groups, scattered through the various layers of society had escaped the system of control. The frequency of collective manumissions of black slaves at the death of a prince or princess reveals some important comparative numbers. In 1823, 177 slaves were manumitted at the death of a princess.[2] Based on the figures provided by travellers, Ralph Austin established some averages, leading to a total estimate of 100,000 slaves.[3] For his part, Louis Ferrière in a letter to Thomas Reade, the British consul in Tunis, estimated there were 167,000 slaves and freed slaves in 1848. Concerning European slaves, the number of women is difficult to determine. Some historians, like Robert C. Davis,[4] estimate their number at around 10%, but these numbers are based on the redemption of slaves; it may simply indicate that women were rarely redeemed. This figure of 10% is especially dubious since the slaves acquired in coastal razzias were more numerous and in these razzias women constituted an average of five out of every eight people taken captive.

Further, the distribution of slaves across regions was not homogenous. In the southeast, the proportion was quite high (especially in the oases). Some villages contained a clear majority of slaves, like those to the south of Gabès. At Tunis, despite continuous supply, the group likely remained a minority of the population, not exceeding a few thousand. The areas of concentration of slaves were thus spread between Tunis, the Sahel and the southeast.[1]

According to Raëd Bader, based on estimates of the Trans-Saharan trade, between 1700 and 1880 Tunisia received 100,000 black slaves, compared to only 65,000 entering Algeria, 400,000 in Libya, 515,000 in Morocco and 800,000 in Egypt.[5]

Organisation

The social organisation of traditional Tunisian society offered a range of specific roles for slaves in Tunis. The agha of slaves, generally the first eunuch of the Bey, was charged with maintaining order among the groups and ruling on disputes which might arise between masters and slaves or among the slaves themselves. Records and accounts confirm the relative autonomy of organisation which was granted to the slaves of Tunis and the protection which the government extended to them, protection which reveals the government's acute awareness of the rules of good conduct and treatment of slaves prescribed by Islam. In effect, by protecting this minority, the government was assured of its unconditional loyalty, especially that of the guards of the Bey, who were recruited from the slaves. In addition to this politico-administrative arrangement, the slaves obviously had their own specific religious organisations as confraternities, whose functions were not limited to the spiritual lives of the members. The confraternities took on multiple social functions which became most apparent after the manumission of a slave. For slaves, manumission usually represented the passage of the slave from the wardship of the master to that of the confraternity, which substituted for the extended family or tribe.

Functions

Economic role

Slavery in Tunisia responded mainly to the needs of the citizen society. However, study of the main businesses of the city of Tunis, which has been performed by many scholars, does not indicate concentrated use of slaves in labour-intensive sectors.[6] The major traditional industries like weaving, making the chéchia or leather continued to be reserved for the local workforce. Labour in these businesses was still performed by free people and one could not attribute slavery to economic needs. However, in the oases of southern Tunisia, groups of slaves were employed in agriculture and especially in irrigation works. It was in the south of the country that slavery continued most prominently after its abolition in 1846 and into the twentieth century. Viviane Pâques relates similar phenomena, "At the oases, slaves were especially in use as domestic servants, for sinking wells and for digging canals. They worked from sunrise to sunset, getting only a plate of couscous for their toil. When they become chouchane, their status is that of khammès and they get a percentage of the harvest. But their workload remains the same..."[7]

Domestic

Female slaves were primarily used as either domestic servants, or as concubines (sex slaves).

On the other hand, the sources are unanimous about the heavy domestic character of slavery in Tunisia. In face the possession of slaves constituted a mark of nobility in Tunis and the almost universal possession of one or more slaves for domestic tasks attests to a pronounced tendency of contempt for physical work, a traditional aristocratic characteristic. Some general practices in the Tunisian court contributed to entrench this tradition: the princes from the Hafsid period down to the Husainid beys solely employed slaves as palace guards and servants in their harem. By integrating slaves into the daily life of the court, the princes provided a model of slave use for the thousands of aristocrats living at court and for the civic nobility.

Government

In addition, as the French doctor and naturalist Jean-André Peyssonnel notes, Christian slaves of European origin who converted to Islam could rise to high positions - even to the chief offices of state, like the Muradid Beys, whose dynasty was founded by a Corsican slave, or several ministers of the Husainid dynasty, such as Hayreddin Pasha, who was captured by corsairs and sold in the Istanbul slave markets. Some princes, like Hammuda Pasha and Ahmed I Bey were even born to slave mothers.

Other slaves of European origin became corsairs themselves after converting to Islam and captured other European slaves (sometimes attacking their own hometowns).

Abolition

On 29 April 1841, Ahmed I Bey had an interview with Thomas Reade who advised him to ban the slave trade. Ahmed I was convinced of the necessity of this action; himself the son of a slave, he was considered open to progress and quick to act against all forms of fanaticism. He decided to ban the export of slaves the same day that he met with Reade. Proceeding in stages, he closed the slave market of Tunis in August and declared in December 1842 that everyone born in the country would thereafter be free.[8]

To alleviate discontent, Ahmed obtained fatwas from the ulama beforehand from the Bach-mufti Sidi Brahim Riahi, which forbade slavery, categorically and without any precedent in the Arab Muslim world. The complete abolition of slavery throughout the country was declared in a decree of 23 January 1846.[9][10] However, although the abolition was accepted by the urban population, it was rejected - according to Ibn Abi Dhiaf - at Djerba, among the Bedouins, and among the peasants who required a cheap and obedient workforce.[11]

This resistance justified the second abolition announced by the French in a decree of Ali III Bey on 28 May 1890.[12] This decree promulgated financial sanctions (in the form of fines) and penal sanctions (in the form of imprisonment) for those who continued to engage in the slave trade or to keep slaves as servants. The colonial accounts tended to pass over the first abolition and focus on the second.

After abolition

Over the second half of the nineteenth century, the majority of the old slaves, male or female, formed an urban underclass, relying on their former masters or living in precarious circumstances (foundouks on the outskirts). Often they work as bread sellers, street merchants, masseurs in the Moorish baths, domestic servants or simple criminals, easily nabbed by the municipal police for drunkenness or petty larceny. Up to 10% of prostitutes in Tunis are descended from former slaves.[13] After abolition, then, a process of impoverishment and social marginalisation of the old slaves took place because enfranchisement had secured legal emancipation but not social freedom.[14]

Gallery

Maison esclaves

Maison esclaves Ancien marché aux esclaves - Médina de Tunis

Ancien marché aux esclaves - Médina de Tunis Lehnert et Landrock - Marché d'esclave, Tunisie, circa 1910

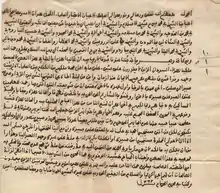

Lehnert et Landrock - Marché d'esclave, Tunisie, circa 1910 Abolition slavery declaration- Ahmed I bey

Abolition slavery declaration- Ahmed I bey Tunisia337

Tunisia337 Marché 2

Marché 2

See also

- Arab slave trade

- Islamic views on slavery

- Stambali

References

- (in French) « Esclaves chrétiens et esclaves noirs à Tunis au XVIIIe siècle », Lucette Valensi, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, vol. 22, n°6, 1967, p. 1267-1288

- Archives nationales de Tunisie, série historique, dossiers relatifs aux familles princières, document 58188

- Ralph Austin, The Transaharian Slave Trade. Essays in the economic history of the Atlantic slave trade, New York Academy Press, 1979

- Robert C. Davis, Esclaves chrétiens. Maîtres musulmans. L'esclavage blanc en Méditerranée (1500-1800), éd. Jacqueline Chambon, Paris, 2006

- (in French) Raëd Bader, Noirs en Algérie, XIXe-XXe siècles, éd. École normale supérieure de Lyon, 20 June 2006

- Pierre Fennec, La transformation des corps de métiers à Tunis sous l'effet d'une économie de type capitaliste, Tunis, 1964

- Viviane Pâques, L'arbre cosmique dans la pensée populaire et dans la vie quotidienne du nord-ouest africain, Paris, 1964

- (in French) César Cantu, Histoire universelle, traduit par Eugène Aroux et Piersilvestro Léopardi, tome XIII, éd. Firmin Didot, Paris, 1847, p. 139

- (in Arabic) Original decree of 23 January 1846 on the enfranchisement of slaves (National archives of Tunisia)

- (in French) French translation of the decree of 23 January 1846 on the enfranchisement of slaves (Portal of Justice and Human rights in Tunisia)

- Ibn Abi Dhiaf, Al Ithaf, tome 4, pp. 89-90

- (in French) Décret du 28 mai 1890, Journal officiel tunisien, 29 May 1890

- Dalenda et Abdelhamid Larguèche, Marginales en terre d'islam, Tunis, éd. Cérès, 1993

- (in French) Affet Mosbah, « Être noire en Tunisie », Jeune Afrique, 11 juillet 2004

Bibliography

- Roger Botte, Esclavages et abolitions en terres d'islam. Tunisie, Arabie saoudite, Maroc, Mauritanie, Soudan, éd. André Versailles, Bruxelles, 2010, ISBN 287495084X.

- Inès Mrad Dali, "De l'esclavage à la servitude," Cahiers d'études africaines, n°179-180, 2005, pp. 935–955 ISSN 0008-0055.

- Abdelhamid Larguèche, Abolition de l'esclavage en Tunisie à travers les archives. 1841-1846, éd. Alif, Tunis, 1990, ISBN 9973716248.

- Ahmed Rahal, La communauté noire de Tunis. Thérapie initiatique et rite de possession, éd. L'Harmattan, Paris, 2000, ISBN 2738485561.

External links

- (in French) « Traite et esclavage des Noirs en Tunisie », Mémoire d'un continent, Radio France internationale, 11 juillet 2009

- (in French) Maria Ghazali, « La régence de Tunis et l'esclavage en Méditerranée à la fin du XVIIIe siècle d'après les sources consulaires espagnoles », Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 2002, vol. 65

- (in French) Documents on the black community of Tunisia