Entheogen

Entheogens are psychoactive substances that induce alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, or behavior[1] for the purposes of engendering spiritual development or otherwise[2] in sacred contexts.[2][3] Anthropological studies have established that entheogens are used for religious, magical, shamanic, or spiritual purposes in many parts of the world. Entheogens have traditionally been used to supplement many diverse practices geared towards achieving transcendence, including divination, meditation, yoga, sensory deprivation, healings, asceticism, prayer, trance, rituals, chanting, imitation of sounds, hymns like peyote songs, drumming, and ecstatic dance. The psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as those experienced in meditation,[4] near-death experiences,[5] and mystical experiences.[4] Ego dissolution is often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.[6]

Nomenclature

The neologism entheogen was coined in 1979 by a group of ethnobotanists and scholars of mythology (Carl A. P. Ruck, Jeremy Bigwood, Danny Staples, Richard Evans Schultes, Jonathan Ott and R. Gordon Wasson). The term is derived from two words of Ancient Greek, ἔνθεος (éntheos) and γενέσθαι (genésthai). The adjective entheos translates to English as "full of the god, inspired, possessed," and is the root of the English word "enthusiasm." The Greeks used it as praise for poets and other artists. Genesthai means "to come into being". Thus, an entheogen is a drug that causes one to become inspired or to experience feelings of inspiration, often in a religious or "spiritual" manner.[7]

Ruck et al. argued that the term hallucinogen was inappropriate owing to its etymological relationship to words relating to delirium and insanity. The term psychedelic was also seen as problematic, owing to the similarity in sound to words about psychosis and also because it had become irreversibly associated with various connotations of the 1960s pop culture. In modern usage, entheogen may be used synonymously with these terms, or it may be chosen to contrast with recreational use of the same drugs. The meanings of the term entheogen was formally defined by Ruck et al.:

In a strict sense, only those vision-producing drugs that can be shown to have figured in shamanic or religious rites would be designated entheogens, but in a looser sense, the term could also be applied to other drugs, both natural and artificial, that induce alterations of consciousness similar to those documented for ritual ingestion of traditional entheogens.

— Ruck et al., 1979, Journal of Psychedelic Drugs[8]

In 2004, David E. Nichols wrote the following about the nomenclature used for serotonergic hallucinogens:[9]

Many different names have been proposed over the years for this drug class. The famous German toxicologist Louis Lewin used the name phantastica earlier in this century, and as we shall see later, such a descriptor is not so farfetched. The most popular names—hallucinogen, psychotomimetic, and psychedelic ("mind manifesting")—have often been used interchangeably. Hallucinogen is now, however, the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the term psychedelic is still the most popular and has held sway for nearly four decades. Most recently, there has been a movement in nonscientific circles to recognize the ability of these substances to provoke mystical experiences and evoke feelings of spiritual significance. Thus, the term entheogen, derived from the Greek word entheos, which means "god within," was introduced by Ruck et al. and has seen increasing use. This term suggests that these substances reveal or allow a connection to the "divine within." Although it seems unlikely that this name will ever be accepted in formal scientific circles, its use has dramatically increased in popular media and internet sites. Indeed, in much of the counterculture that uses these substances, entheogen has replaced psychedelic as the name of choice, and we may expect to see this trend continue.

History

Entheogens have been used by indigenous peoples for thousands of years.[13] Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BCE, confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus.[14] Giorgio Samorini has proposed several examples of the cultural use of entheogens that are found in the archaeological record,[15][16] some conclusions of which have been called into question by R. Gordon Wasson and Erwin Panofsky and other art historians (see the Christianity section, below).

According to Ruck, Eyan, and Staples, the familiar shamanic entheogen of which the Eurasians brought knowledge was Amanita muscaria. This fungus could not be cultivated and thus had to be gathered from the wild, making its use compatible with a nomadic lifestyle rather than a settled agriculturalist. When they reached the world of the Caucasus and the Aegean, they encountered wine, the entheogen of Dionysus, who brought it with him from his birthplace in the mythical Nysa when he returned to claim his Olympian birthright. The Eastern Mediterraneans "recognized it as the entheogen of Zeus, and their own traditions of shamanism, the Amanita and the 'pressed juice' of Soma – but better, since no longer unpredictable and wild, the way it was found among the Hyperboreans: as befit their own assimilation of agrarian modes of life, the entheogen was now cultivable."[17] Robert Graves, in his foreword to The Greek Myths, hypothesizes that the ambrosia of various pre-Hellenic tribes was Amanita muscaria and perhaps psilocybin mushrooms of the genus Panaeolus. Amanita muscaria was regarded as divine food, according to Ruck and Staples, not something to be indulged in, sampled lightly, or profaned. It was seen as the food of the gods, their ambrosia, and as mediating between the two realms, and it was said that Tantalus's crime was inviting commoners to share his ambrosia.

Uses

Entheogens have been used in various ways, e.g., as part of established religious rituals or as aids for personal spiritual development ("plant teachers").[18][19]

In religion

Shamans all over the world and in different cultures have traditionally used entheogens, especially psychedelics, for their religious experiences. In these communities, the absorption of drugs leads to dreams (visions) through sensory distortion. The psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as those experienced in meditation,[20] and mystical experiences.[20] Ego dissolution is often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.[6]

Entheogens used in the contemporary world include biota like peyote (Native American Church[21]), extracts like ayahuasca (Santo Daime,[22] União do Vegetal[23]), and synthetic drugs like 2C-B (Sangoma, Nyanga, and Amagqirha[24][25][26]). Entheogens also play an important role in contemporary religious movements such as the Rastafari movement.[27]

Hinduism

Bhang is an edible preparation of cannabis native to the Indian subcontinent. It has been used in food and drink as early as 1000 BCE by Hindus in ancient India.[28] The earliest known reports regarding the sacred status of cannabis in the Indian subcontinent come from the Atharva Veda estimated to have been written sometime around 2000–1400 BCE,[29] which mentions cannabis as one of the "five sacred plants... which release us from anxiety" and that a guardian angel resides in its leaves. The Vedas also refer to it as a "source of happiness," "joy-giver," and "liberator," and in the Raja Valabba, the gods send hemp to the human race.[30]

Buddhism

It has been suggested that the Amanita muscaria mushroom was used by the Tantric Buddhist mahasiddha tradition of the 8th to 12th century.[31]

In the West, some modern Buddhist teachers have written about the usefulness of psychedelics. The Buddhist magazine Tricycle devoted their entire fall 1996 edition to this issue.[32] Some teachers such as Jack Kornfield have suggested the possibility that psychedelics could complement Buddhist practice, bring healing and help people understand their connection with everything which could lead to compassion.[33] Kornfield warns however that addiction can still be a hindrance. Other teachers, such as Michelle McDonald-Smith, expressed views that saw entheogens as not conducive to Buddhist practice ("I don't see them developing anything").[34]

The fifth of The Five Precepts, the ethical code in the Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist traditions, states that adherents must: "abstain from fermented and distilled beverages that cause heedlessness."[35] The Pali Canon, the scripture of Theravada Buddhism, depicts refraining from alcohol as essential to moral conduct because intoxication causes a loss of mindfulness. Although the Fifth Precept only names a specific wine and cider, this has traditionally been interpreted to mean all alcoholic beverages.

Judaism

The primary advocate of the religious use of cannabis in early Judaism was Polish anthropologist Sula Benet, who claimed that the plant kaneh bosem קְנֵה-בֹשֶׂם mentioned five times in the Hebrew Bible, and used in the holy anointing oil of the Book of Exodus, was cannabis.[36] According to theories that hold that cannabis was present in Ancient Israelite society, a variant of hashish is held to have been present.[37] In 2020, it was announced that cannabis residue had been found on the Israelite sanctuary altar at Tel Arad dating to the 8th century BCE of the Kingdom of Judah, suggesting that cannabis was a part of some Israelite rituals at the time.[38]

While Benet's conclusion regarding the psychoactive use of cannabis is not universally accepted among Jewish scholars, there is general agreement that cannabis is used in Talmudic sources to refer to hemp fibers, not hashish, as hemp was a vital commodity before linen replaced it.[39] Lexicons of Hebrew and dictionaries of plants of the Bible such as by Michael Zohary (1985), Hans Arne Jensen (2004), and James A. Duke (2010) and others identify the plant in question as either Acorus calamus or Cymbopogon citratus, not cannabis.[40]

Christianity

Alcohol was clearly used, historically, in Christian religious ceremonies, i.e., that of the Eucharist or Lord's Supper (i.e., Communion practices), where Christians consume bread and wine as elements in remembrance of the broken body and shed blood of Jesus Christ.[41] In the Christian biblical writings, which date to antiquity, both the common use of wine and the subject of the abuse of alcohol are subjects that appear (in the latter case, indicating it was a popular issue requiring address).[42] In many modern contexts of Eucharistic and related practices, in particular, those in Protestant congregations, grape juice often substitutes for wine, and in Catholic and Orthodox, the amount of wine consumed in modern ceremonies is, in any case, far below the levels required for the participant to have an entheogenic experience.[43]

Apart from alcohol, Christian denominations otherwise generally disapprove of the use of most drugs used illicitly in pursuit of entheogenic experiences. David Hillman, in a major work on medicative and recreational drug use in Greek and Roman antiquity, suggests that drug use was indeed found in the early history of the Church, although this was a component argument rejected by his doctoral committee and so did not appear in his dissertation.[44] Generally speaking, Michael Winkelman, writing in 2019, argues in support of the role of "psilocybin mushrooms in the ancient evolution of human religions," stating that:

This prehistoric mycolatry[45] persisted into the historic era in the major religious traditions of the world, which often left evidence of these practices in sculpture, art, and scriptures. ... But even through new entheogenic combinations were introduced, complex societies generally removed entheogens from widespread consumption, restricted them in private and exclusive spiritual practices of the leaders, and often carried out repressive punishment of those who engaged in entheogenic practices.[46]

As of this date, the question of the extent of entheogen use in practices through Christian history is viewed as remaining poorly considered by academic or independent scholars.

The question of whether visionary plants were used in pre-Theodosian Christianity, including by heretical or quasi-Christian groups, was reported by Celdrán and Ruck to be distinct from the extent to which visionary plants were utilized or forgotten in later Christianity.[47][48] The same is true of the question of possible distinctives of use by groups within orthodox Catholic practice, e.g., elites versus laity (e.g., where Ruck and colleagues suggest use of Datura by early Spanish church elites, based on appearances of the plant of origin in images).[49] In 2001, classical philologist Mark Hoffman and colleagues suggested widespread use of "visionary" (entheogenic) plants in cultures surrounding the emerging Christian movement, and so too in among early Christians, with a gradual reduction of the use of entheogens in Christianity over history.[50][48]

Jan Irvin and Michael Hoffman—the former including both authors in their publication, but the latter omitting the former in his—argue strongly in 2007 in The Journal of Higher Criticism[51][52] for revision of the classical rejection of a strong entheogenic presence in Christian art and history, stating:

It is most remarkable that none of these scholars–Ramsbottom, Panofsky, Wasson, or Allegro–explicitly consider and address the question, “What was the extent of entheogen use throughout Christian history and in the surrounding cultural context?” Wasson and Allegro share the unexamined and untested assumption that while entheogen use was the original inspiration for religions, it was vanishingly rare in Christianity and the surrounding culture.

These authors go on to state their perspective, at odds with Panofsky, Wasson, and others, and argue that the opposing scholars' "unjustified combination of premises has resulted in a standoff of positions", and that their scholarly opponents' historic objection to entheogenic arguments "all share the same shaky foundation, producing inconsistencies and self-contradictions."[53][54] The response follows from the appearance, in R. Gordon Wasson's book, Soma, of a letter from art historian Erwin Panofsky (and arguments surrounding the same) that communicates those art scholars were aware of "mushroom trees" in "Romanesque and early Gothic art", but that "the plant [in the fresco in question had] nothing whatever to do with mushrooms", going on to state that "the similarity with Amanita muscaria is purely fortuitous". Panofsky continues:

The Plaincourault fresco is only one example - and, since the style is provincial, a particularly deceptive one—of a conventionalized tree type, prevalent in Romanesque and early Gothic art, which art historians actually refer to as a ‘mushroom tree’ or in German, Pilzbaum. It comes about by the gradual schematization of the impressionistically rendered Italian pine tree in Roman and early Christian painting, and there are hundreds of instances exemplifying this development—unknown of course to mycologists. ... What the mycologists have overlooked is that the medieval artists hardly ever worked from nature but from classical prototypes which in the course of repeated copying became quite unrecognizable.[53][54]

Peyotism

The Native American Church (NAC) is also known as Peyotism and Peyote Religion. Peyotism is a Native American religion characterized by mixed traditional as well as Protestant beliefs and by sacramental use of the entheogen peyote.

The Peyote Way Church of God believes that "Peyote is a holy sacrament when taken according to our sacramental procedure and combined with a holistic lifestyle."[55]

Santo Daime

Santo Daime is a syncretic religion founded in the 1930s in the Brazilian Amazonian state of Acre by Raimundo Irineu Serra,[56] known as Mestre Irineu. Santo Daime incorporates elements of several religious or spiritual traditions, including Folk Catholicism, Kardecist Spiritism, African animism and indigenous South American shamanism, including vegetalismo.

Ceremonies – trabalhos (Brazilian Portuguese for "works") – are typically several hours long and are undertaken sitting in silent "concentration," or sung collectively, dancing according to simple steps in geometrical formation. Ayahuasca referred to as Daime within the practice, which contains several psychoactive compounds, is drunk as part of the ceremony. The drinking of Daime can induce a strong emetic effect which is embraced as both emotional and physical purging.

União do Vegetal

União do Vegetal (UDV) is a religious society founded on July 22, 1961, by José Gabriel da Costa, known as Mestre Gabriel. The translation of União do Vegetal is Union of the Plants referring to the sacrament of the UDV, Hoasca tea (also known as ayahuasca). This beverage is made by boiling two plants, Mariri (Banisteriopsis caapi) and Chacrona (Psychotria viridis), both of which are native to the Amazon rainforest.

In its sessions, UDV members drink Hoasca Tea for the effect of mental concentration. In Brazil, the use of Hoasca in religious rituals was regulated by the Brazilian Federal Government's National Drug Policy Council on January 25, 2010. The policy established legal norms for the religious institutions that responsibly use this tea. In 2006, in the case of Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal, the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously affirmed the UDV's right to use Hoasca tea in its religious sessions in the United States.[57]

By region

Africa

The best-known entheogen-using culture of Africa is the Bwitists, who used a preparation of the root bark of Tabernanthe iboga.[58] Although the ancient Egyptians may have been using the sacred blue lily plant in some of their religious rituals or just symbolically, it has been suggested that Egyptian religion once revolved around the ritualistic ingestion of the far more psychoactive Psilocybe cubensis mushroom, and that the Egyptian White Crown, Triple Crown, and Atef Crown were evidently designed to represent pin-stages of this mushroom.[59] There is also evidence for the use of psilocybin mushrooms in Ivory Coast.[60] Numerous other plants used in shamanic ritual in Africa, such as Silene capensis sacred to the Xhosa, are yet to be investigated by western science. A recent revitalization has occurred in the study of southern African psychoactives and entheogens (Mitchell and Hudson 2004; Sobiecki 2002, 2008, 2012).[61]

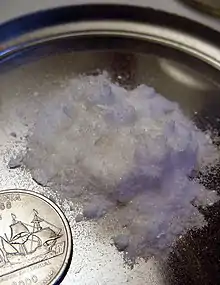

Among the amaXhosa, the artificial drug 2C-B is used as an entheogen by traditional healers or amagqirha over their traditional plants; they refer to the chemical as Ubulawu Nomathotholo, which roughly translates to "Medicine of the Singing Ancestors".[62][25][63]

Americas

Entheogens have played a pivotal role in the spiritual practices of most American cultures for millennia. The first American entheogen to be subject to scientific analysis was the peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii). One of the founders of modern ethnobotany, Richard Evans Schultes of Harvard University documented the ritual use of peyote cactus among the Kiowa, who live in what became Oklahoma. While it was used traditionally by many cultures of what is now Mexico, in the 19th century its use spread throughout North America, replacing the toxic mescal bean (Calia secundiflora). Other well-known entheogens used by Mexican cultures include the alcoholic Aztec sacrament, pulque, ritual tobacco (known as "picietl" to the Aztecs, and "sikar" to the Maya, from where the word "cigar" derives), psilocybin mushrooms, morning glories (Ipomoea tricolor and Turbina corymbosa), and Salvia divinorum.

Datura wrightii is sacred to some Native Americans and has been used in ceremonies and rites of passage by Chumash, Tongva, and others. Among the Chumash, when a boy was 8 years old, his mother would give him a preparation of momoy to drink. This supposed spiritual challenge should help the boy develop the spiritual well-being that is required to become a man. Not all of the boys undergoing this ritual survived.[64] Momoy was also used to enhance spiritual wellbeing among adults. For instance, during a frightening situation, such as when seeing a coyote walk like a man, a leaf of momoy was sucked to help keep the soul in the body.

The mescal bean Sophora secundiflora was used by the shamanic hunter-gatherer cultures of the Great Plains region. Other plants with ritual significance in North American shamanism are the hallucinogenic seeds of the Texas buckeye and jimsonweed (Datura stramonium). Paleoethnobotanical evidence for these plants from archaeological sites shows they were used in ancient times thousands of years ago.[65]

In South America there is a long tradition of using the Mescaline-containing cactus Echinopsis pachanoi.[66] Archaeological studies have found evidence of use going back to the pre-Columbian era, to Moche culture, Nazca culture,[67] and Chavín culture.

Eurasia

In the mountains of western China, significant traces of THC, the compound responsible for cannabis’ psychoactive effects, have been found in wooden bowls, or braziers, excavated from a 2,500-year-old cemetery.[68]

John Marco Allegro argued that early Jewish and Christian cultic practice was based on the use of Amanita muscaria, which was later forgotten by its adherents,[69] but this view has been widely disputed.[70]

In 440 BCE, Herodotus in Book IV of the Histories, documents that the Scythians inhaled cannabis in funeral ceremonies, stating they "take some of this hemp-seed, and … throw it upon the red hot stones" and when it released a vapor, the "Scyths, delighted, shout[ed] for joy."[68]

A theory that naturally-occurring gases like ethylene used by inhalation may have played a role in divinatory ceremonies at Delphi in Classical Greece received popular press attention in the early 2000s, yet has not been conclusively proven.[71]

Mushroom consumption is part of the culture of Eurasian in general, with particular importance to Slavic and Baltic peoples. Some academics argue that the use of psilocybin- and/or muscimol-containing mushrooms was an integral part of the ancient culture of the Rus' people.[72]

Oceania

There are no known uses of entheogens by the Māori of New Zealand aside from a variant species of kava,[73] although some modern scholars have claimed that there may be evidence of psilocybin mushroom use.[74] Natives of Papua New Guinea are known to use several species of entheogenic mushrooms (Psilocybe spp, Boletus manicus).[75]

Kava or kava kava (Piper Methysticum) has been cultivated for at least 3,000 years by a number of Pacific island-dwelling peoples. Historically, most Polynesian, many Melanesian, and some Micronesian cultures have ingested the psychoactive pulverized root, typically taking it mixed with water. In these traditions, taking kava is believed to facilitate contact with the spirits of the dead, especially relatives and ancestors.[76]

Research

Notable early testing of the entheogenic experience includes the Marsh Chapel Experiment, conducted by physician and theology doctoral candidate Walter Pahnke under the supervision of psychologist Timothy Leary and the Harvard Psilocybin Project. In this double-blind experiment, volunteer graduate school divinity students from the Boston area almost all claimed to have had profound religious experiences subsequent to the ingestion of pure psilocybin.

Beginning in 2006, experiments have been conducted at Johns Hopkins University, showing that under controlled conditions psilocybin causes mystical experiences in most participants and that they rank the personal and spiritual meaningfulness of the experiences very highly.[77][78]

Except in Mexico, research with psychedelics is limited due to ongoing widespread drug prohibition. The amount of peer-reviewed research on psychedelics has accordingly been limited due to the difficulty of getting approval from institutional review boards.[79] Furthermore, scientific studies on entheogens present some significant challenges to investigators, including philosophical questions relating to ontology, epistemology and objectivity.[80]

Legal status

Some countries have legislation that allows for traditional entheogen use.

Australia

Between 2011 and 2012, the Australian Federal Government was considering changes to the Australian Criminal Code that would classify any plants containing any amount of DMT as "controlled plants".[81] DMT itself was already controlled under current laws. The proposed changes included other similar blanket bans for other substances, such as a ban on any and all plants containing mescaline or ephedrine. The proposal was not pursued after political embarrassment on realisation that this would make the official Floral Emblem of Australia, Acacia pycnantha (golden wattle), illegal. The Therapeutic Goods Administration and federal authority had considered a motion to ban the same, but this was withdrawn in May 2012 (as DMT may still hold potential entheogenic value to native or religious peoples).[82]

United States

In 1963 in Sherbert v. Verner the Supreme Court established the Sherbert Test, which consists of four criteria that are used to determine if an individual's right to religious free exercise has been violated by the government. The test is as follows:

For the individual, the court must determine

- whether the person has a claim involving a sincere religious belief, and

- whether the government action is a substantial burden on the person's ability to act on that belief.

If these two elements are established, then the government must prove

- that it is acting in furtherance of a "compelling state interest", and

- that it has pursued that interest in the manner least restrictive, or least burdensome, to religion.

This test was eventually all-but-eliminated in Employment Division v. Smith 494 U.S. 872 (1990) which held that a "neutral law of general applicability" was not subject to the test. Congress resurrected it for the purposes of federal law in the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993.

In City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) RFRA was held to trespass on state sovereignty, and application of the RFRA was essentially limited to federal law enforcement. In Gonzales v. O Centro Espírita Beneficente União do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (2006), a case involving only federal law, RFRA was held to permit a church's use of a DMT-containing tea for religious ceremonies.

Some states have enacted State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts intended to mirror the federal RFRA's protections.

Peyote is listed by the United States DEA as a Schedule I controlled substance. However, practitioners of the Peyote Way Church of God, a Native American religion, perceive the regulations regarding the use of peyote as discriminating, leading to religious discrimination issues regarding about the U.S. policy towards drugs. As the result of Peyote Way Church of God, Inc. v. Thornburgh the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 was passed. This federal statute allow the "Traditional Indian religious use of the peyote sacrament", exempting only use by Native American persons.

In literature

Many works of literature have described entheogen use; some of those are:

- The drug melange (spice) in Frank Herbert's Dune universe acts as both an entheogen (in large enough quantities) and an addictive geriatric medicine. Control of the supply of melange was crucial to the Empire, as it was necessary for, among other things, faster-than-light (folding space) navigation.

- Consumption of the imaginary mushroom anochi [enoki] as the entheogen underlying the creation of Christianity is the premise of Philip K. Dick's last novel, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer, a theme that seems to be inspired by John Allegro's book.

- Aldous Huxley's final novel, Island (1962), depicted a fictional psychoactive mushroom – termed "moksha medicine" – used by the people of Pala in rites of passage, such as the transition to adulthood and at the end of life.[83][84]

- Bruce Sterling's Holy Fire novel refers to the religion in the future as a result of entheogens, used freely by the population.[85]

- In Stephen King's The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger, Book 1 of The Dark Tower series, the main character receives guidance after taking mescaline.

- The Alastair Reynolds novel Absolution Gap features a moon under the control of a religious government that uses neurological viruses to induce religious faith.

- A critical examination of the ethical and societal implications and relevance of "entheogenic" experiences can be found in Daniel Waterman and Casey William Hardison's book Entheogens, Society & Law: Towards a Politics of Consciousness, Autonomy and Responsibility (Melrose, Oxford 2013). This book includes a controversial analysis of the term entheogen arguing that Wasson et al. were mystifying the effects of the plants and traditions to which it refers.

See also

- List of Acacia species known to contain psychoactive alkaloids

- List of plants used for smoking

- List of psychoactive plants

- List of psychoactive plants, fungi, and animals

- List of substances used in rituals

- N,N-Dimethyltryptamine

- Psilocybin mushrooms

- Psychedelic therapy

- Psychoactive Amanita mushrooms

- Psychoactive cacti

- Psychology of religion

- Scholarly approaches to mysticism

- Stela of the cactus bearer

References

- "CHAPTER 1 Alcohol and Other Drugs". The Public Health Bush Book: Facts & approaches to three key public health issues. ISBN 0-7245-3361-3. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015.

- Rätsch, Christian, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications pub. Park Street Press 2005

- Souza, Rafael Sampaio Octaviano de; Albuquerque, Ulysses Paulino de; Monteiro, Júlio Marcelino; Amorim, Elba Lúcia Cavalcanti de (October 2008). "Jurema-Preta (Mimosa tenuiflora [Willd.] Poir.): a review of its traditional use, photochemistry, and pharmacology". Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 51 (5): 937–947. doi:10.1590/S1516-89132008000500010.

- Millière, Raphaël; Carhart-Harris, Robin L.; Roseman, Leor; Trautwein, Fynn-Mathis; Berkovich-Ohana, Aviva (4 September 2018). "Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6137697. PMID 30245648.

- Timmermann, Christopher; Roseman, Leor; Williams, Luke; Erritzoe, David; Martial, Charlotte; Cassol, Héléna; Laureys, Steven; Nutt, David; Carhart-Harris, Robin (15 August 2018). "DMT Models the Near-Death Experience". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1424. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01424. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6107838. PMID 30174629.

- Letheby, Chris; Gerrans, Philip (30 June 2017). "Self unbound: ego dissolution in psychedelic experience". Neuroscience of Consciousness. 2017 (1): nix016. doi:10.1093/nc/nix016. ISSN 2057-2107. PMC 6007152. PMID 30042848.

- Godlaski, Theodore M. (2011). "The God within". Substance Use and Misuse. 46 (10): 1217–1222. doi:10.3109/10826084.2011.561722. PMID 21692597. S2CID 39317500.

- Carl A. P. Ruck; Jeremy Bigwood; Danny Staples; Jonathan Ott; R. Gordon Wasson (January–June 1979). "Entheogens". Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 11 (1–2): 145–146. doi:10.1080/02791072.1979.10472098. PMID 522165. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.

- Nichols DE (February 2004). "Hallucinogens". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 131–181. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002. PMID 14761703.

- "Mescaline : D M Turner". www.mescaline.com.

- Rudgley, Richard. "The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances". mescaline.com. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "Peyote". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Carod-Artal, F.J. (1 January 2015). "Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures". Neurología (English Edition). 30 (1): 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010. ISSN 2173-5808. PMID 21893367.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2014). The Amazons : lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton. pp. 147–149. ISBN 9780691147208. OCLC 882553191.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Samorini, Giorgio (1997). "The 'Mushroom-Tree' of Plaincourault". Eleusis (8): 29–37.

- Samorini, Giorgio (1998). "The 'Mushroom-Trees' in Christian Art". Eleusis (1): 87–108.

- Staples, Danny; Carl A.P. Ruck (1994). The World of Classical Myth: Gods and Goddesses, Heroines and Heroes. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 0-89089-575-9. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Tupper, K.W. (2003). "Entheogens & education: Exploring the potential of psychoactives as educational tools" (PDF). Journal of Drug Education and Awareness. 1 (2): 145–161. ISSN 1546-6965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2007.

- Tupper, K.W. (2002). "Entheogens and existential intelligence: The use of plant teachers as cognitive tools" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Education. 27 (4): 499–516. doi:10.2307/1602247. JSTOR 1602247. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2004.

- Millière, Raphaël; Carhart-Harris, Robin L.; Roseman, Leor; Trautwein, Fynn-Mathis; Berkovich-Ohana, Aviva (4 September 2018). "Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6137697. PMID 30245648.

- Calabrese, Joseph D. (1997). "Spiritual healing and human development in the Native American church: Toward cultural psychiatry of peyote". Psychoanalytic Review. 84 (2): 237–255. PMID 9211587.

- Santos, R. G.; Landeira-Fernandez, J.; Strassman, R. J.; Motta, V.; Cruz, A. P. M. (2007). "Effects of ayahuasca on psychometric measures of anxiety, panic-like and hopelessness in Santo Daime members". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 112 (3): 507–513. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.012. PMID 17532158.

- de Rios, Marlene Dobkin; Grob, Charles S. (2005). "Interview with Jeffrey Bronfman, Representative Mestre for the União do Vegetal Church in the United States". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 37 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1080/02791072.2005.10399800. PMID 16149332. S2CID 208178224.

- Chen Cho Dorge (20 May 2010). "2CB chosen over traditional entheogens by South African healers". Evolver.net. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- The Nexus Factor - An Introduction to 2C-B Erowid

- Ubulawu Nomathotholo Pack Photo by Erowid. © 2002 Erowid.org

- Chawane, Midas H. (2014). "The Rastafarian Movement in South Africa: A Religion or Way of Life?". Journal for the Study of Religion. 27 (2): 214–237.

- Staelens, Stefanie (10 March 2015). "The Bhang Lassi Is How Hindus Drink Themselves High for Shiva". Vice.com. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Courtwright, David (2001). Forces of Habit: Drugs and the Making of the Modern World. Harvard Univ. Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-674-00458-2.

- Touw, Mia (January 1981). "The Religious and Medicinal Uses of Cannabis in China, India and Tibet". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 13 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.1981.10471447. PMID 7024492.

- Hajicek-Dobberstein (1995). "Soma siddhas and alchemical enlightenment: psychedelic mushrooms in Buddhist tradition". American Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 48 (2): 99–118. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01292-L. PMID 8583800.

- Tricycle: Buddhism & Psychedelics, Fall 1996 https://tricycle.org/magazine-issue/fall-1996/

- Kornfield, Jack; "Bringing Home the Dharma: Awakening Right Where You Are," excerpted at "Psychedelics and Spiritual Practice - Jack Kornfield". Archived from the original on 5 October 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2015./

- Stolaroff, M. J. (1999). "Are Psychedelics Useful in the Practice of Buddhism?". Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 39 (1): 60–80. doi:10.1177/0022167899391009. S2CID 145220039.

- O'Brien, Barbara. "The Fifth Buddhist Precept". about.com.

- Benet, S. (1975). "Early Diffusions and Folk Uses of Hemp", in Vera Rubin; Lambros Comitas (eds.), Cannabis and Culture. Moutan, pp. 39–49.

- Warf, Barney. "High points: An historical geography of cannabis." Geographical Review 104.4 (2014): 414-438. Page 422: "Psychoactive cannabis is mentioned in the Talmud, and the ancient Jews may have used hashish (Clarke and Merlin 2013)."

- Arie, Eran; Rosen, Baruch; Namdar, Dvory (2020). "Cannabis and Frankincense at the Judahite Shrine of Arad". Tel Aviv. 47: 5–28. doi:10.1080/03344355.2020.1732046. S2CID 219763262.

- Roth, Cecil. (1972). Encyclopedia Judaica. 1st Ed. Volume 8. p. 323. OCLC 830136076. Note, the second edition of the Encyclopedia Judaica no longer mentions Sula Benet but continues to maintain that hemp is "the plant Cannabis sativa called kanbus in Talmudic literature," but now adds, "Hashish is not mentioned, however in Jewish sources." See p. 805 in Vol. 8 of the 2nd edition.

- Lytton J. Musselman Figs, dates, laurel, and myrrh: plants of the Bible and the Quran 2007 p73

- For coverage of this topic, with full citations, see the article Sacramental wine.

- For coverage of this topic, with full citations, see the article Alcohol in the Bible.

- The Lord's Supper or Eucharist is a tradition instituted in remembrance of the Last Supper, where Jesus Christ offered bread and wine to his disciples during the Passover meal, referring to the bread as "my body" and the wine as "my blood." See "Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. Eucharist". Britannica.com. Retrieved 16 May 2019. and Wright, N. T. (2015). The Meal Jesus Gave Us: Understanding Holy Communion (Revised ed.). Louisville, Kentucky. p. 63. ISBN 9780664261290.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), and for primary sources, Luke 22:19–20 and 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 It is considered a central tradition, either a sacrament (e.g., in the Catholic Church) or an ordinance (e.g., in Protestant churches. Despite the use, in Protestant churches, of some form of grape juice in practice of the Lord's Supper in modern times, stances within Christianity on the use of alcoholic wine as part the Eucharist vary; in some Catholic Churches, mustum—grape juice in which fermentation has begun but has been suspended without altering the nature of the juice—is used, see "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. In others, such as the Coptic Church, wine is mixed in part with water, see "Sacrament of the Eucharist: Rite of Sanctification of the Chalice". Copticchurch.net. Retrieved 16 May 2019. In Protestant churches, grape juice is used per se (i.e., it is entirely unfermented). - Hillman, D.C.A. (July 2008). The Chemical Muse: Drug Use and the Roots of Western Civilization (First ed.). Stuttgart, Germany: Thomas Dunne Books (Holtzbrinck-Macmillan-St. Martin’s). ISBN 9780312352493. For the fact that the arguments of The Chemical Muse were rejected by Hillman's dissertation committee, see the preface to the book.

- For use of this term to describe use of fungi in worship in Mesoamerica, see Wasson, Robert Gordon (1980). The Wondrous Mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. Ethno-mycological Studies. Vol. 7. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. xxvi, 189, etc. ISBN 978-0070684430. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- Winkelman, Michael (1 June 2019). "Evidence for Entheogen Use in Prehistory and World Religions". Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 3 (2): 43–62. doi:10.1556/2054.2019.024. S2CID 203501063. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- Celdrán, José & Ruck, Carl (2002). "Daturas for the Virgin". Entheos: The Journal of Psychedelic Spirituality. San Diego, CA: Entheos. 1 (2 (winter)). Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Note, the appearing links, original and archived, are to a table of contents webpage that presents no further link to an actual article whose content can be verified. Note also, the publisher, Entheos, no longer appears to be active. - Entheos, the journal, was originally a print-on-demand publication that premiered in 2001 and appears to have been produced as a limited number of issues at least through 2012, but now appears defunct. See Roberts, Thomas B. (2002). "Myth, Mind, and Molecule—Entheos: The Journal of Psychedelic" (journal review). Maps. 12 (1 [Sex, Spirit, and Psychedelics]): 43. Retrieved 13 March 2023., and CAP Staff (2022). "Mark Alwin Hoffman" (contributor profile). CAP-Press.com. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press (CAP). Retrieved 13 March 2023., and Entheomedia Staff (13 March 2023). "Entheos" (contributor profile). CAP-Press.com. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press (CAP). Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- Ruck, Carl; Staples, Blaise; Celdran, Jose Alfredo & Hoffman, Mark (2007). The Hidden World: Survival of Pagan Shamanic Themes in European Fairytales. Durhem, NC: Carolina Academic Press. pp. 160, 330, 388. ISBN 9781594601446. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hoffman, Mark; Ruck, Carl & Staples, Blaise (2001). "Conjuring Eden: Art and the Entheogenic Vision of Paradise". Entheos: The Journal of Psychedelic Spirituality. San Diego, CA: Entheos. 1 (1 (summer)): 13–50. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Note, the publisher, Entheos, no longer appears to be active. Note also, the earlier appearing links, original and archived, were to a table of contents webpage that presented no further link an actual article whose content can be verified. - Price, Robert M. (1994). "The Journal of Higher Criticism: This Publication May be Hazardous to Your Cherished Assumptions!". Drew.edu/jhc/. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- Notable here is the fact that this journal is published by Robert M. Price—see Price, Robert M. (1994). "Introducing the Journal of Higher Criticism". Drew.edu/jhc/. Retrieved 13 March 2023. [Access to this introduction is via a link at this cited page.]—who, in introducing the new journal, criticized modern biblical scholarship as "a toothless tiger or worse yet, covert apologetics wearing the Esau-mask of criticism", where his scholarly emphasis had been to deny the historicity of the existence of the person of Jesus (contrary to the mainstream scholarly consensus that held, as of the early 2000s, that Jesus was a historical figure who lived in 1st-century Roman Judea, with evidence at least that he had been baptized and crucified). On these points see Herzog, William R. (2005). Prophet and Teacher: An Introduction to the Historical Jesus. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 0664225284., Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 168–173. ISBN 0-664-25703-8., and Levine, Any-Jill (2006). The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780691009926.

There is a consensus of sorts on a basic outline of Jesus' life. Most scholars agree that Jesus was baptized by John, debated with fellow Jews on how best to live according to God's will, engaged in healings and exorcisms, taught in parables, gathered male and female followers in Galilee, went to Jerusalem, and was crucified by Roman soldiers during the governorship of Pontius Pilate (26-36 CE). But, to use the old cliché: the devil is in the details.

- Hoffman, Michael (2007). "Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita". Journal of Higher Criticism. Madison, NJ: The Institute for Higher Critical Studies at Drew University. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007.

- Hoffman, Michael & Irvin, Jan (2009) [March 5, 2006]. "Wasson and Allegro on the Tree of Knowledge as Amanita". Journal of Higher Criticism. Tempe, AZ: LogosMedia.com, formerly Gnostic Media.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Peyote Way Church of God » Overview". peyoteway.org.

- Mestre Irineu photos

- 546 U.S. 418 (February 21, 2006) ("The Government has not carried the burden expressly placed on it by Congress in the Religious Freedom Restoration Act [which would permit them to ban the UDV's entheogenic use of Hoasca tea].").

- Bwiti: An Ethnography of the Religious Imagination in Africa Archived 28 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine by James W. Fernandez, Princeton University Press, 1982

- S.R. Berlant (2005). "The entheomycological origin of Egyptian crowns and the esoteric underpinnings of Egyptian religion" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 102 (2005): 275–88. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.028. PMID 16199133. S2CID 19297225. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2009.

- Samorini, Giorgio (1995). "Traditional Use of Psychoactive Mushrooms in Ivory Coast?". Eleusis. 1: 22–27. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- "Ethnobotanical Research". ethnobotany.co.za. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "2CB chosen over traditional entheogen's by South African healers". Tacethno.com. 27 March 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- Ubulawu Nomathotholo Pack Photo by Erowid. 2002 Erowid.org

- Cecilia Garcia, James D. Adams (2005). Healing with medicinal plants of the west - cultural and scientific basis for their use. Abedus Press. ISBN 0-9763091-0-6.

- Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices and Cultures. ABC-CLIO. 2004. p. 18.

- Bussmann, Rainer W; Sharon, Douglas (7 November 2006). "Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2: 47. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. ISSN 1746-4269. PMC 1637095. PMID 17090303.

- Socha, Dagmara M.; Sykutera, Marzena; Orefici, Giuseppe (1 December 2022). "Use of psychoactive and stimulant plants on the south coast of Peru from the Early Intermediate to Late Intermediate Period". Journal of Archaeological Science. 148: 105688. Bibcode:2022JArSc.148j5688S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105688. ISSN 0305-4403. S2CID 252954052.

- Meilan Solly (13 June 2019). "The First Evidence of Smoking Pot Was Found in a 2,500-Year-Old Pot". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Allegro, John Marco (1970). The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross: A Study of the Nature and Origins of Christianity within the Fertility Cults of the Ancient Near East. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-12875-5.

- Taylor, Joan E. (2012). The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-19-955448-5.

- "History : Oracle at Delphi May Have Been Inhaling Ethylene Gas Fumes". Ethylene Vault. Erowid.org. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- "НАРКОТИКИ.РУ | Наркотики на Руси. Первый этап: Древняя Русь". www.narkotiki.ru.

- "Macropiper Excelsum - Maori Kava". Entheology.org. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "Psilocybian mushrooms in New Zealand". Erowid.org.

- "Benjamin Thomas Ethnobotany & Anthropology Research Page". Shaman-australis.com. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Singh, Yadhu N., ed. (2004). Kava from ethnology to pharmacology. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 1420023373.

- R. R. Griffiths; W. A. Richards; U. McCann; R. Jesse (7 July 2006). "Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance". Psychopharmacology. 187 (3): 268–283. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5. PMID 16826400. S2CID 7845214.

- MacLean, Katherine A.; Johnson, Matthew W.; Griffiths, Roland R. (2011). "Mystical Experiences Occasioned by the Hallucinogen Psilcybin Lead to Increases in the Personality Domain of Openness". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (11): 1453–1461. doi:10.1177/0269881111420188. PMC 3537171. PMID 21956378.

- Nutt, David J.; King, Leslie A.; Nichols, David E. (2013). "Effects of Schedule I Drug Laws on Neuroscience Research and Treatment Innovation". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 14 (8): 577–85. doi:10.1038/nrn3530. PMID 23756634. S2CID 1956833.

- Tupper, Kenneth W.; Labate, Beatriz C. (2014). "Ayahuasca, Psychedelic Studies and Health Sciences: The Politics of Knowledge and Inquiry into an Amazonian Plant Brew". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (2): 71–80. doi:10.2174/1874473708666150107155042. PMID 25563448.

- "Consultation on implementation of model drug schedules for Commonwealth serious drug offences". Australian Government, Attorney-General's Department. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

- "Aussie DMT Ban". American Herb Association Quarterly Newsletter. 27 (3): 14. Summer 2012.

- Gunesekera, Romesh (26 January 2012). "Book of a Lifetime: Island, By Aldous Huxley". Independent UK. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Schermer, MH (2007). "Brave New World versus Island--utopian and dystopian views on psychopharmacology". Med Health Care Philos. 10 (2): 119–28. doi:10.1007/s11019-007-9059-1. PMC 2779438. PMID 17486431.

- Sterling, Bruce (1997). Holy Fire. p. 228.

Further reading

- Harner, Michael, The Way of the Shaman: A Guide to Power and Healing, Harper & Row Publishers, NY 1980

- Rätsch, Christian; "The Psychoactive Plants, Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications"; Park Street Press; Rochester Vermont; 1998/2005; ISBN 978-0-89281-978-2

- Pegg, Carole (2001). Mongolian Music, Dance, & Oral Narrative: Performing Diverse Identities. U of Washington P. ISBN 9780295981123. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Roberts, Thomas B. (editor) (2001). Psychoactive Sacramentals: Essays on Entheogens and Religion San Francisco: Council on Spiritual Practices.

- Roberts, Thomas B. (2006) "Chemical Input, Religious Output—Entheogens" Chapter 10 in Where God and Science Meet: Vol. 3: The Psychology of Religious Experience Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood.

- Roberts, Thomas, and Hruby, Paula J. (1995–2003). Religion and Psychoactive Sacraments: An Entheogen Chrestomathy https://web.archive.org/web/20071111053855/http://csp.org/chrestomathy/ [Online archive]

- Shimamura, Ippei (2004). "Yellow Shamans (Mongolia)". In Walter, Mariko Namba; Neumann Fridman, Eva Jane (eds.). Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 649–651. ISBN 9781576076453. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014.

- Tupper, Kenneth W. (2014). "Entheogenic Education: Psychedelics as Tools of Wonder and Awe" (PDF). MAPS Bulletin. 24 (1): 14–19.

- Tupper, Kenneth W. (2002). "Entheogens and Existential Intelligence: The Use of Plant Teachers as Cognitive Tools" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Education. 27 (4): 499–516. doi:10.2307/1602247. JSTOR 1602247. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Tupper, Kenneth W. (2003). "Entheogens & Education: Exploring the Potential of Psychoactives as Educational Tools" (PDF). Journal of Drug Education and Awareness. 1 (2): 145–161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2007.

- Stafford, Peter. (2003). Psychedelics. Ronin Publishing, Oakland, California. ISBN 0-914171-18-6.

- Carl Ruck and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth 1994. Introductory excerpts

- Huston Smith, Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals, 2000, Tarcher/Putnam, ISBN 1-58542-034-4

- Daniel Pinchbeck,"Ten Years of Therapy in One Night", The Guardian UK (2003), describes Daniel's second journey with Iboga facilitated by Dr. Martin Polanco at the Ibogaine Association clinic in Rosarito, Mexico.

- Giorgio Samorini 1995 "Traditional use of psychoactive mushrooms in Ivory Coast?" in Eleusis 1 22-27 (no current url)

- M. Bock 2000 "Māori kava (Macropiper excelsum)" in Eleusis - Journal of Psychoactive Plants & Compounds n.s. vol 4 (no current url)

- Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers by Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, Christian Ratsch - ISBN 0-89281-979-0

- John J. McGraw, Brain & Belief: An Exploration of the Human Soul, 2004, AEGIS PRESS, ISBN 0-9747645-0-7

- J.R. Hale, J.Z. de Boer, J.P. Chanton and H.A. Spiller (2003) Questioning the Delphic Oracle, 2003, Scientific American, vol 289, no 2, 67-73.

- The Sacred Plants of our Ancestors by Christian Rätsch, published in TYR: Myth—Culture—Tradition Vol. 2, 2003–2004 - ISBN 0-9720292-1-4

- Yadhu N. Singh, editor, Kava: From Ethnology to Pharmacology, 2004, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-32327-4

External links

Media related to Entheogens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Entheogens at Wikimedia Commons