Esztergom

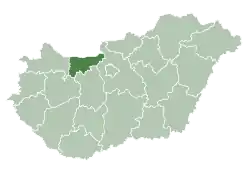

Esztergom (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈɛstɛrɡom] ⓘ; German: Gran; Latin: Solva or Strigonium; Slovak: Ostrihom, known by alternative names) is a city with county rights in northern Hungary, 46 kilometres (29 miles) northwest of the capital Budapest. It lies in Komárom-Esztergom County, on the right bank of the river Danube, which forms the border with Slovakia there. Esztergom was the capital of Hungary from the 10th until the mid-13th century when King Béla IV of Hungary moved the royal seat to Buda.

Esztergom | |

|---|---|

Top left: Dark Gate, Top upper right: Esztergom Cathedral, Top lower right: Saint Adalbert Convention Center, Middle left: Kis-Duna Setany (Little Danube Promenade), Middle right: Saint Stephen's Square, Bottom: Esztergom Castle Hill and Danube River | |

Flag | |

| Nicknames: | |

Esztergom  Esztergom | |

| Coordinates: 47°47′8″N 18°44′25″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Central Transdanubia |

| County | Komárom-Esztergom |

| District | Esztergom |

| Established | around 972 |

| Capital of Hungary | 972–1249 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ádám Hernádi (2019–) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 100.35 km2 (38.75 sq mi) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 28,165[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 2500–2509 |

| Area code | (+36) 33 |

| Website | www |

Esztergom is the seat of the prímás (see Primate) of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary, and the former seat of the Constitutional Court of Hungary. The city has a Christian Museum with the largest ecclesiastical collection in Hungary. Its cathedral, Esztergom Basilica, is the largest church in Hungary. Near the Basilica there is a campus of the Pázmány Péter Catholic University.

Toponym

The Roman town was called Solva. The medieval Latin name was Strigonium.[3] The first early medieval mention is "ſtrigonensis [strigonensis] comes" (1079-1080).[4]

The first interpretation of the name was suggested by Antonio Bonfini. He tried to explain it from Istrogranum, "city at the confluence of Ister (the Greek name of the Danube river) and Gran (the Latin name of the river Hron)". This interpretation is still popular.[5][6][7] Viktor Récsey attempted to derive the name from Germanic languages. After the conquest of the country by Charlemagne, the Franks should give the name Osterringun to their easternmost castle; as a comparison, a reference is made to the town of Östringen. Pavel Jozef Šafárik tried to explain the name from Slavic ostřehu (locus custodius, munitus).[8] Gyula Pauler suggested a Slavic personal name Stigran without a deeper analysis of its origin.[9]

In 1927, Konrad Schünemann summarized these older views and proposed the origin in a Slavic stem strěg ("custodia", guard).[10] This theory was later extended by Ján Stanislav who also explained the origin of the initial vowel missing in Latin and later Czech sources (Střehom).[11] The introduction of a vowel before the initial consonant group is a regular change in the Hungarian language (Stephan → István, strecha → esztercha), but the initial "O" in later Slavic forms can be explained by an independent change–an incorrect decomposition of the Slavic prepositional form. Both authors noticed the high number of Slavic placenames in the region (Vyšegrad, Pleš, Kokot, Drug, Komárno, Toplica, etc.) and similar Slavic names in other countries (Strzegom, Střehom, Stregowa, etc.). Both authors believed that the stem strěg was a part of the Slavic personal name, but Šimon Ondruš suggests a straightforward etymology. The Proto-Slavic stregti – to watch, to guard, present participle stregom, strägom – a guard post.[12][lower-alpha 1] The later Slavic form was created by an incorrect decomposition as follows: vъ Strägome (in Strägom) → vo Strägome → v Osträgome like Slovak Bdokovce → Obdokovce, Psolovce → Obsolovce.[12]

Lajos Kiss considered the name to be of uncertain origin, potentially derived also from Slavic strgun (a tanner) or Proto-Bulgaric estrogin käpe, estrigim küpe – a leather armor.[4][12] However, the last theory is sharply criticized by Šimon Ondruš as obsolete and unreliable, because of its dependency on later sources, the high number of Slavic names in the region and missing adoption of the word in the Hungarian language.[12]

Other names of the town are Croatian Ostrogon, Polish Ostrzyhom, Serbian Ostrogon and Estergon (also Turkish), Slovak Ostrihom and Czech Ostřihom (the archaic name is Střehom). The German name is Gran (German: ⓘ), like the German name of river Garam.[13] Istergom, Esztergom. Ister, the old name of Danube. Gom/hun/ is arch like, gomb/hun/ is (coat button), gömb/hun/ is (sphere).

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

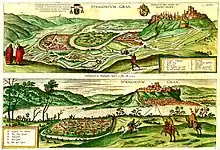

Esztergom is one of the oldest towns in Hungary.[14] Esztergom, as it existed in the Middle Ages, now rests under today's town. The results of the most recent archeological excavations reveal that the Várhegy (Castle Hill) and its vicinity have been inhabited since the end of the Ice Age 20,000 years ago. The first people known by name were the Celts from Western Europe, who settled in the region in about 350 BC. A flourishing Celtic settlement existed on the Varhegy until the region was conquered by Rome. Thereafter it became an important frontier town of Pannonia, known by the name of Salvio Mansio, Salvio, or Solva. By the seventh century the town was called Stregom and later Gran, but soon reverted to the former, which evolved into Esztergom by the thirteenth century. The German and Avar archaeological finds found in the area reveal that these people settled there following the period of the migrations that were caused by the fall of the Roman Empire.

At about 500 AD, Slavic peoples immigrated into the Pannonian Basin. In the 9th century, the territory was mostly under Frankish control, and it might have been part of Great Moravia too. In Old Slavonic language, it was called Strěgom ("guard"), as it was strategic point of control for the Danube valley.

The Magyars entered the Pannonian Basin in 896 AD and conquered it systematically, succeeding fully in 901. In 960, the ruling prince of the Hungarians, Géza, chose Esztergom as his residence. His son, Vajk, who was later called Saint Stephen of Hungary, was born in his palace built on the Roman castrum on the Várhegy (Castle Hill) around 969–975. In 973, Esztergom served as the starting point of an important historical event: during Easter of that year, Géza sent a committee to the international peace conference of Emperor Otto I in Quedlinburg. He offered peace to the Emperor and asked for missionaries.

The prince's residence stood on the northern side of the hill. The center of the hill was occupied by a basilica dedicated to St. Adalbert, who, according to legend, baptised St. Stephen. The Church of St. Adalbert was the seat of the archbishop of Esztergom, the head of the Roman Catholic Church in Hungary. By that time, significant numbers of craftsmen and merchants had settled in the city.

Stephen's coronation took place in Esztergom on either Christmas Day 1000 or January 1, 1001. From the time of his rule up to the beginning of the 13th century, the only mint for the country operated here. During the same period, the castle of Esztergom ("Estergon Kalesi" in Turkish) was built. It served not only as the royal residence until the Mongol siege of Esztergom in 1241 (during the first Mongol invasion), but also as the center of the Hungarian state, religion, and Esztergom county. The archbishop of Esztergom was the leader of the ten bishoprics founded by Stephen. The archbishop was often in charge of important state functions and had the exclusive right to crown kings.

The settlements of royal servants, merchants and craftsmen at the foot of the Várhegy (Castle Hill) developed into the most significant town during the age of the Árpád dynasty– these being the most important area of the economic life of the country. According to the Frenchman Odo of Deuil, who visited the country in 1147, "the Danube carries the economy and treasures of several countries to Esztergom".

The town council was made up of the richest citizens of the town (residents of French, Spanish, Dutch, and Italian origin) who dealt with commerce. The coat of arms of Esztergom emerged from their seal in the 13th century. This was the town where foreign monarchs could meet Hungarian kings. For example, Emperor Conrad II met Géza II in this town (1147). Another important meeting took place when the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa visited Béla III. The historians traveling with them all agree on the richness and significance of Esztergom. Arnold of Lübeck, the historian with Frederick Barbarossa, called Esztergom the capital of Hungarian people ("quae Ungarorum est metropolis").

In the beginning of the 13th century Esztergom was the center of the country's political and economic life. This is explained by the canon of Nagyvárad, Rogerius of Apulia, who witnessed the first devastation of the country during the Tatar invasion siege of Esztergom and wrote in his Carmen Miserabile ("Sad Song"): "since there was no other town like Esztergom in Hungary, the Tatars (siege of Esztergom) were considering crossing the Danube to pitch a camp there", which was exactly what happened after the Danube froze. The capital of the Árpád-age was destroyed in a vicious battle. Though, according to the documents that remained intact, some of the residents (those who escaped into the castle) survived and new residents settled in the area and soon started rebuilding the town, it lost its leading role. Béla IV gave the palace and castle to the archbishop, and changed his residence to Buda. Béla IV and his family, however, were buried in the Franciscan church in Esztergom which had been destroyed during the invasion and which had been rebuilt by Béla IV in 1270.

Following these events, the castle was built and decorated by the bishops. The center of the king's town, which was surrounded by walls, was still under royal authority. A number of different monasteries did return or settle in the religious center.

Meanwhile, the citizenry had been fighting to maintain and reclaim the rights of towns against the expansion of the church within the royal town. In the chaotic years after the fall of the House of Árpád, Esztergom suffered another calamity: in 1304, the forces of Wenceslaus II, the Czech king occupied and raided the castle. In the years to come, the castle was owned by several individuals: Róbert Károly and then Louis the Great patronized the town. In 1327 Kovácsi, the most influential suburb of the town, lying in the southeast, was united with Esztergom. The former suburb had three churches with mainly blacksmith, goldsmith, and coiner residents.

In the 14th and 15th centuries Esztergom saw events of great importance and became one of the most influential acropolises of Hungarian culture along with Buda. Their courts, which were similar to the royal courts of Buda and Visegrád, were visited by such kings, scientists, and artists as Louis the Great, Sigismund of Luxembourg, King Matthias Corvinus, Galeotto Marzio, Regiomontanus, the famous astronomer Marcin Bylica and Georg von Peuerbach, Pier Paolo Vergerio and Antonio Bonfini, King Matthias's historian, who, in his work praises the constructive work of János Vitéz, King Matthias's educator. He had a library and an observatory built next to the cathedral. As Bonfini wrote about his masterpiece, his palace and terraced gardens: "he had a spacious room for knights built in the castle. In front of that, he built a wonderful loggia of red marble. In front of the room, he built the Chapel of Sibyls, whose walls were decorated with paintings of the sybils. On the walls of the knights' room, not only the likeness of all the kings could be found, but also the Scythian ancestors. He also had a double garden constructed, which was decorated with columns and a corridor above them. Between the two gardens, he built a round tower of red marble with several rooms and balconies. He had Saint Adalbert's Basilica covered with glass tiles". King Matthias's widow, Beatrix of Aragon, lived in the castle of Esztergom for ten years (1490–1500).

The time of the next resident, Archbishop Tamás Bakócz (d. 1521) gave the town significant monuments. In 1507 he had Italian architects build the Bakócz chapel, which is the earliest and most significant Renaissance building which has survived in Hungary. The altarpiece of the chapel was carved from white marble by Andrea Ferrucci, a sculptor from Fiesole in 1519.

The Ottoman conquest of Mohács in 1526 brought a decline to the previously flourishing Esztergom as well. In the Battle of Mohács, the archbishop of Esztergom died. In the period between 1526 and 1543, when two rival kings reigned in Hungary, Esztergom was besieged six times. At times it was the forces of Ferdinand I or John Zápolya, at other times the Ottomans attacked. Finally, in 1530, Ferdinand I occupied the castle. He put foreign mercenaries in the castle, and sent the chapter and the bishopric to Nagyszombat and Pozsony (that is why some of the treasury, the archives and the library survived).

In 1543 Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent attacked the castle and captured it. The castle then remained under the Ottoman Empire.

Esztergom (as Estergon) became the centre of an Ottoman sanjak controlling several counties, and also a significant castle on the northwest border of the Ottoman Empire – the main clashing point to prevent attacks on the mining towns of the highlands, Vienna and Buda. In 1594, during the unsuccessful but devastating siege by the walls of the Víziváros, Bálint Balassa, the first Hungarian poet who gained European significance, died in action. The most devastating siege took place in 1595 when the castle was reclaimed by the troops of Count Karl von Mansfeld and Count Mátyás Cseszneky. The price that had to be paid, however, was high. Most of the buildings in the castle and the town that had been built in the Middle Ages were destroyed during this period, and there were only uninhabitable, smothered ruins to welcome the liberators.

In 1605 the Ottomans regained control over the castle as well as the whole region again, maintaining their rule until 1683. Though the Ottomans were mainly engaged in building and fortifying the castle, they also built significant new buildings including mosques, minarets and baths. These structures, along with the contemporary buildings, were destroyed in the siege of 1683 resulting in the liberation of Esztergom - though some Turkish buildings prevailed up to the beginning of the 18th century. The last time the Ottoman forces attacked Esztergom was in 1685. During the following year Buda was liberated as well. During these battles János Bottyán, captain of the cavalry, later the legendary figure of the Rákóczi war of independence disappeared. All that had been rebuilt at the end of the century was destroyed and burnt down during Ferenc Rákóczi's long lasting, but finally successful siege.

The destroyed territory was settled by Hungarian, Slovakian and German settlers. This was when the new national landscape developed. In the area where there had previously been 65 Hungarian villages, only 22 were rebuilt. Though the reconstructed town received its free royal rights, in size and significance it was only a shadow of its former self.

Handcrafts gained strength and in around 1730, there were 17 independent crafts operating in Esztergom. Wine-culture was also of major significance. This was also the period when the Baroque view of the downtown area and the Víziváros (Watertown) were developed. The old town's main characteristic is the simplicity and moderateness of its citizen Baroque architecture. The most beautiful buildings can be found around the marketplace (Széchenyi square).

In 1761 the bishopric regained control over the castle, where they started the preliminary processes of the reconstruction of the new religious center: the middle of the Várhegy (Castle Hill), the remains of Saint Stephen and Saint Adalbert churches were carried away to provide room for the new cathedral.

Although the major construction work and the resettlement of the bishopric (1820) played a significant role in the town's life, the pace of Esztergom's development gradually slowed down, and work on the new Basilica came to a halt.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Esztergom gained significance owing to its cultural and educational institutions as well as to being an administrative capital. The town's situation turned worse after the Treaty of Trianon of 1920, after which it became a border town and lost most of its previous territory.

This was also the place where the poet Mihály Babits spent his summers from 1924 to his death in 1941. The poet's residence was one of the centers of the country's literary life; he had a significant effect on intellectual life in Esztergom.

Esztergom had one of the oldest Jewish communities in Hungary. They had a place of worship here by 1050. King Charles I (Caroberto) gifted a plot to the community for a cemetery in 1326.

According to the 1910 census, 5.1% of the population were Jewish, while the 1941 census found a population of 1510 Jews. The community maintained an elementary school until 1944. Jewish shops were ordered to be closed on April 28, 1944, and a short-lived ghetto was set up on May 11. The former Jewish shops were handed over to non-Jews on June 9. The inmates of the ghetto were sent to Komárom in early June, then deported to Auschwitz on June 16, 1944. Two forced labor units, whose members were mainly Esztergom Jews, were executed en masse near Ágfalva, on the Austrian border in January 1945.

Soviet troops captured the town on December 26, 1944, but were pushed back by the Germans on January 6, 1945, who were finally ousted on March 21, 1945.

The Mária Valéria bridge, connecting Esztergom with the city of Štúrovo in Slovakia was rebuilt in 2001 with the support of the European Union. Originally it was inaugurated in 1895, but the retreating German troops destroyed it in 1944. A new thermal and wellness spa opened in November 2005.

Architecture

One of the most important events of the 1930s was the exploration and renovation of the remains of the palace of the Árpád period. This again put Esztergom in the center of attention. Following World War II, Esztergom was left behind as one of the most severely devastated towns. However, reconstruction slowly managed to erase the traces of the war, with two of Esztergom's most vital characteristics gaining significance: due to its situation it was the cultural center of the area (more than 8,000 students were educated at its elementary, secondary schools and college ). On the other hand, as a result of the local industrial development it has become a vital basis for the Hungarian tool and machinery industry.

This town, with its spectacular scenery and numerous memorials, a witness of the struggles of Hungarian history, is popular mostly with tourists interested in the beauties of the past and art. However, the town seems to regain its role in the country's politics, and its buildings and traditions revive.

The castle and palace

The winding streets of the town, with its church towers create a historical atmosphere. Below Esztergom Basilica, at the edge of the mountain stand the old walls and bastions – the remains of the castle of Esztergom. The remains of one section of the royal palace and castle that had been built during the Ottoman rule had been buried in the ground up until the 1930s.

Most parts of the palace were explored and restored in the period between 1934 and 1938, but even today there are archeological excavations in progress. Passing through the narrow stairs, alleys, under arches and gates built in Romanesque style, a part of the past seems to come to life. This part of the palace was built in the time of King Béla III. With his wife - the daughter of Louis VII - French architects arrived and constructed the late-Roman and early-Gothic building at the end of the 12th century.

The frescoes of the palace chapel date from the 12th-14th centuries, while on the walls of the mottes, some of the most beautiful paintings of the early Hungarian Renaissance can be admired (15th century). From the terrace of the palace one can admire the landscape of Esztergom. Under the terrace are the houses and churches of the Bishop-town section, or Víziváros (Watertown) and the Primate's Palace. Opposite the palace is the Saint Thomas hill, and surrounded by the mountains and the Danube. The walls of the castle still stand on the northern part of the Basilica. From the northern rondella one can admire the view of Párkány on the other side of the Danube as well as the Szentgyörgymező, the Danube valley, and the So-called 'Víziváros' (Watertown) districts.

Esztergom Basilica

Those traveling to Esztergom today can admire the most monumental construction of Hungarian Classicism, the Basilica, which silently rules the landscape above the winding Danube, surrounded by mountains.

The building that might be considered the symbol of the town is the largest church in Hungary and was built according to the plans of Pál Kühnel, János Páckh and József Hild from 1822 to 1869. Ferenc Liszt wrote the Mass of Esztergom for this occasion. The classicist church is enormous: the height of the dome is 71.5 metres (235 feet); it has giant arches and an enormous altar-piece by Michelangelo Grigoletti. On one side, in the Saint Stephen chapel, the glittering relics of Hungarian and other nations' saints and valuable jewellery can be seen. On the south side, the Bakócz Chapel, the only one that survived the Middle Ages, can be seen. The builders of the Basilica had disassembled this structure into 1600 pieces, and incorporated it into the new church in its original form.

The treasury houses many masterpieces of medieval goldsmith's works. The western European masters' hands are praised by such items as the crown silver cross that has been used since the 13th century, the ornate chalices, Francesco Francia's processional cross, the upper part of the well-known 'Matthias-Calvary' which is decorated in the rare ronde-bosse enamel technique. The Treasury also has a vast collection of traditional Hungarian and European textiles, including chasubles, liturgical vestments and robes.

The sound of the enormous bell hung in the southern tower can be heard from kilometers away. From the top of the large dome, visitors can see a breath-taking view: to the north, east and south the ranges of the Börzsöny, Visegrád, Pilis and Gerecse mountains rule the landscape, while to the west, in the valley of the Danube one can see as far as the Small Plains.

Viziváros

The Víziváros (Watertown) section was named after being built on the banks of the Kis- and Nagy Duna (Small and Great Danube). Its fortresses, walls, bastions and Turkish rondellas can still be seen by the walk on the banks of the Danube. By the northern end of the wall, on the bank of the Nagy-Duna, an interesting memorial is put, a stone table with Ottoman Turkish writings commemorates Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent's victorious siege of 1543. The narrow, winding streets within the walls hide the remains of Turkish mosques and baths.

Along the delightful streets of the Víziváros (Watertown), surrounded by Baroque and Classicist buildings stands the Primate's Palace, designed by József Lippert (1880–82). The Keresztény Múzeum (Christian museum), founded by Archbishop János Simor, is located in this building. It houses a rich collection of Hungarian panel pictures and sculpture of the Middle Ages as well as Italian and western-European paintings and handicrafts (13th-18th centuries). This is where one can admire the chapel-like structure of the late Gothic 'Úrkoporsó' (Lord's coffin) from Garamszentbenedek that is decorated by painted wooden sculptures (c. 1480), the winged altar-piece by Thomas of Coloswar (1427), paintings by Master M.S. (1506), the gothic altars from Upper Historical Hungary (Felvidék), handicrafts of Italian, German and Flemish artists from the 13th–17th centuries, tapestries and ceramics.

The building of the Balassa Bálint Museum that was built in Baroque style on medieval bases and is located in Víziváros (Watertown), served as the first town hall of Esztergom county after the Turks had been driven out of the region.

The parish-church in the centre of the Víziváros (Watertown), which was built by the Jesuits between 1728 and 1738, and the single-towered Franciscan churches are also masterpieces of Baroque architecture.

Cathedral Library

The Cathedral Library standing in the southern part of the town, which was built in 1853 according to plans by József Hild is one of the richest religious libraries of Hungary, accommodating approximately 250,000 books, among which several codices and incunabula can be found, such as the Latin explanation of the 'Song of Songs' from the 12th century, the 'Lövöföldi Corvina' originating from donations of King Matthias, or the Jordánszky Codex, which includes the Hungarian translation of the Bible from 1516 to 1519. Along with Bakócz and Ulászló graduals, they conserve also the Balassa Bible, in which Balassa's uncle, Balassa András wrote down the circumstances of his birth and death.

Szent Tamás-hegy

The main sight of the nearby 'Szent Tamás-hegy' (Saint Thomas Hill - Szenttamás) is the Baroque Calvary, with the Classicist chapel on the top of the hill, which was built to commemorate the heroes who died for Esztergom. The hill was named after a church built by Bishop Lukács Bánffy in memoriam the martyr Saint Thomas Becket, who had been his fellow student at the University of Paris. The church and the small castle which the Turks built there were destroyed a long time ago. On its original spot, the top of the hill, the narrow winding streets and small houses that were built by the masters who were working on the construction of the Basilica at the beginning of the previous century, have an atmosphere that is similar to that of Tabán in Buda. At the foot of the hill are the swimming pool and the Classicist building of the Fürdő Szálló (Bath Hotel). This is where Lajos Kossuth stayed in 1848 on one of his recruiting tours.

On the southern slopes of the hill there is a Mediterranean, winding path with stairs that lead to the Baroque Saint Stephen chapel.

Széchényi Square and the Town Hall

The main square of the town is the Széchényi square. Of the several buildings of Baroque, Rococo and Classicist style, there is one that catches everyone's eyes: the Town Hall. Originally, it used to be the single-floor curia of Vak Bottyán (János Bottyán, Bottyán the Blind), the Kuruc general (1689). The first floor was constructed on its top in 1729. The house burnt down in the 1750s. It was rebuilt in accordance with the plans of a local architect, Antal Hartmann. Upon its façade there is a red marble carving which presents the coat of arms of Esztergom (a palace within the castle walls, protected by towers, with the Árpáds' shields below.) On the corner of the building the equestrian statue of Vak Bottyán (created by István Martsa) commemorates the original owner of the house.

The Trinity-statue in the middle of the square was created by György Kiss in 1900. In Bottyán János Street, near the Town Hall, there are well decorated Baroque houses. This is where the Franciscan church is located (built between 1700 and 1755). Opposite this building there is a Baroque palace which used to belong to the Sándor Earl family.

Other churches

In the direction of the Kis Duna, the downtown parish-church, built by the architect Ignác Oratsek can be admired. A bit farther is the Classicist Church of Saint Anne. The orthodox church at 60 Kossuth Lajos street was built around 1770 by Serbian settlers in Esztergom.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1785 | 5,492 | — |

| 1850 | 8,544 | +55.6% |

| 1869 | 8,780 | +2.8% |

| 1880 | 8,932 | +1.7% |

| 1890 | 9,349 | +4.7% |

| 1900 | 17,909 | +91.6% |

| 1910 | 17,881 | −0.2% |

| 1920 | 17,963 | +0.5% |

| 1930 | 17,354 | −3.4% |

| 1941 | 22,171 | +27.8% |

| 1949 | 20,104 | −9.3% |

| 1960 | 23,021 | +14.5% |

| 1970 | 26,965 | +17.1% |

| 1980 | 30,373 | +12.6% |

| 1990 | 29,841 | −1.8% |

| 2001 | 29,041 | −2.7% |

| 2011 | 28,926 | −0.4% |

| 2021 | 28,165 | −2.6% |

| *Source:[15] *Note:[16] | ||

Languages and ethnic groups

The city and the neighbouring territories became devastated due to the Ottoman wars. Esztergom was repopulated by mostly ethnic Hungarians, some Germans and Slovaks in the late 17th and the early 18th centuries.[17] According to András Vályi, the population of Esztergom was mostly Hungarian in 1796, and the German and Slovak minorities were conversant with the Hungarian language.[17] Elek Fényes described Esztergom as mostly Hungarian by language in 1851.[18] Based on the 1880 census, the city (with Szentgyörgymező, Szenttamás and Víziváros) had 14,944 inhabitants, of whom there were 13,340 (89.3%) Hungarians, 755 (5.1%) Germans and 321 (2.1%) Slovaks by native language.[19]

According to the 2011 census the total population of Esztergom was 28,926, of whom there were 24,155 (83.5%) Hungarians, 729 (2.5%) Romani, 527 (1.8%) Germans and 242 (0.8%) Slovaks by ethnicity.[20] 13.6% of the total population did not declare their ethnicity.[21] In Hungary people can declare multiple ethnic background, so other people declared Hungarian and a minority one together.[22]

Religion

Historically, Esztergom has been the seat of the Catholic Church in Hungary and the privilege of 1708 banned non-Catholics from the city (excluding the small Serbian Orthodox minority).[23] Thus, the population was almost exclusively Roman Catholic in 1851.[18]

The 1869 census showed 14,512 people (with Szentgyörgymező, Szenttamás and Víziváros), 13,567 (93.5%) Roman Catholic, 718 (4.9%) Jewish, 130 (0.9%) Hungarian Reformed (Calvinist), 68 (0.5%) Lutheran and 27 (0.2%) Eastern Orthodox.[24]

At the 2011 census, there were 13,127 (45.4%) Roman Catholic, 1,647 (5.7%) Hungarian Reformed, 211 (0.7%) Lutheran and 160 (0.6%) Greek Catholic. 3,807 people (13.2%) were irreligious and 418 (1.5%) Atheist, while 9,046 people (31.3%) did not declare their religion.[20]

Industry

The Magyar Suzuki Corporation plant opened in 1992, as the European base of the Japanese automotive manufacturer Suzuki. It has a production capacity of 300,000 vehicles per year and it is the biggest employing company in the city, with 3,100 employees.[25]

Climate

| Climate data for Esztergom | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.4 (61.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.8 (33.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.8 (19.8) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36 (1.4) |

35 (1.4) |

31 (1.2) |

40 (1.6) |

59 (2.3) |

67 (2.6) |

51 (2.0) |

56 (2.2) |

42 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

56 (2.2) |

45 (1.8) |

557 (21.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64 | 98 | 132 | 172 | 230 | 227 | 249 | 239 | 173 | 139 | 72 | 53 | 1,848 |

| Source: CLIMATE DATA[26] | |||||||||||||

Notable residents

- Andrew II (c. 1177 – 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, King of Hungary and Croatia (1205 - 1235), Prince of Halych (1188 - 1189/1190, 1208/1209 - 1210).[27]

- Arcadius Avellanus (1851 – 1935), Hungarian-American scholar of Latin, proponent of Living Latin

- Tamás Bakócz (1442 – 1521 in Esztergom) a Hungarian archbishop, cardinal and statesman.[28]

- Helene von Bolváry (1892–1943), Hungarian actress

- János Bottyán (1643 – 1709), a Hungarian kuruc general

- Charles I of Hungary (1288–1342) crowned King of Hungary at Esztergom in 1301.[29]

- Ugrin Csák, archbishop of Kalocsa, Hungary (1219 - 1241)

- Imre Csáky (1672 – 1732), Hungarian Roman Catholic cardinal

- Blessed Eusebius of Esztergom (1200 - 1270), Hungarian canon, hermit, founder of the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit

- Anett György (1996 -), Hungarian racing driver

- Tamás Hajnal (1981-), Hungarian footballer

- László Horváth (1962 -), Hungarian politician

- Saint Irene of Hungary (1088 – 1134), Hungarian-born Byzantine empress

- Judith of Hungary (ca. 969 - ca. 988), Hungarian princess, member of the House of Árpád

- Márta Kurtág (1927 – 2019), classical pianist

- Osvát Laskai (1450 – 1511), Hungarian Franciscan friar, preacher, teacher of theology, head of the friaries of Esztergom and Pest

- Ludwig Lichtscheing (? - 1886), Hungarian rabbi

- Attila Menyhárd Ph.D., Hungarian lawyer, professor of civil law, head of the Civil Law Department on the Faculty of Law at the University of Budapest

- Alojzije Mišić (1859 – 1942), Croatian Bishop of Mostar-Duvno and Apostolic Administrator of Trebinje-Mrkan (1912 - 1942)

- Jozef Murgaš (1864 – 1929), Slovak inventor, architect, botanist, painter, and Roman Catholic priest, contributor to the wireless telegraphy and the development of mobile communications and wireless transmission of information and human voice.

- Tibor Pézsa (1935 -), Hungarian fencer

- László Ernő Pintér (1942 - 2002), Hungarian Franciscan priest, malacologist

- Blessed Sebestyén (? - 1007), Hungarian Benedictine missionary, prelate and politician, Archbishop of Esztergom (1002 - 1007)

- Stephen I of Hungary (975 – 1038), the first King of Hungary.[30]

- Sándor Urbanik (born 1964), Hungarian race walker

- Vladislaus II (1456 – 1516), King of Bohemia (1471 - 1516), King of Hungary and Croatia (1490 - 1516)

- Blessed Yolanda of Poland (1235 – 1298) Hungarian nun of the order of Poor Clares

- Zlaudus (? - ca.1262), bishop of Veszprém in the Kingdom of Hungary (1245 - 1262), Chancellor of Hungary in 1226

- Nándor Zsolt (1887 - 1936), conductor, composer and the professor of violin at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music

Twin towns – sister cities

Gallery

Castle Hill

Castle Hill Esztergom Cathedral at night

Esztergom Cathedral at night The White Tower of Castle

The White Tower of Castle HNM Castle Museum

HNM Castle Museum_2.jpg.webp) Downtown Church

Downtown Church Watertown Church

Watertown Church Saint Anne Church or Round Church

Saint Anne Church or Round Church

_1.JPG.webp) Ister-Fountain

Ister-Fountain

See also

References

- "Revelation 14 LEB - - Bible Gateway".

- Esztergom, KSH

- "Maître Roger : Carmen miserabile". Site de Philippe Remacle. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Kiss, Lajos (1980). Földrajzi nevek etimológiai szótára (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 209. ISBN 963-05-2277-2.

- Magyarország régészeti topográfiája, Volume 5, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1979, p. 83, ISBN 9789630514453

- István Filep, Zoltán Nagy (editors), Esztergom, Magyar Távirati Iroda, 1989, p. 10, ISBN 9789637262364

- Communicationes de historia artis medicinae, Volumes 27–29, Budapest (Hungary)., Orvostörténetï közlemények, Országos Orvostörténeti Könyvtár, Semmelweis Orvostörténeti Múzeum, 1963, p. 123

- Schünemann, Konrad (1927). "Esztergom, der ungarische Name der Stadt Gran". Ungarische Jahrbücher (in German). Vol. 7. Berlin-Leipzig. p. 178.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pauler, Gyula (1899). A magyar nemzet története az Árpádházi királyok alatt (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Könyvkiadók és Könyvterjesztők Egyesülése és az Állami Könyvterjesztő Vállalat közös kiadása. p. 27.

- Schünemann 1927, p. 180.

- Stanislav, Ján (1941). "Zo slovenských miestnych názvov". Slovenská reč (in Slovak). Martin: Matica slovenská (2–3): 42.

- Ondruš, Ondruš (2002). Odtajnené trezory slov II. Martin: Matica slovenská. p. 222. ISBN 80-7090-659-6.

- "Revised Atlas of World History". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 6 March 2007.

- "The history of our town". Esztergom.hu Portal. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- 1785-1990 (census data): Magyarország történeti statisztikai helységnévtára, 6. Komárom Esztergom megye, Központi Statisztikai Hivatal, Budapest, 1995, ISBN 963-215-094-5 – 2001-2011 (census data): Gazetteer of Hungary / Esztergom

- Including Szentgyörgymező, Szenttamás and Víziváros since 1895 and Pilisszentlélek since 1985.

- András Vályi: Magyar Országnak leírása, Buda, 1796 Online

- Elek Fényes: Magyarország geographiai szótára, Pest, 1851 Online

- A Magyar Szent Korona Országaiban az 1881. év elején végrehajtott népszámlálás főbb eredményei megyék és községek szerint részletezve, Országos Magyar Királyi Statisztikai Hivatal, Budapest, 1882 Online

- Hungarian census, Komárom-Esztergom county, tables 4.1.6.1, 4.1.7.1

- Gazetteer of Hungary / Esztergom

- Hungarian census 2011 - final data and methodology

- Privilege of Esztergom, 1708

- Az 1869. évi népszámlálás vallási adatai, TLA Teleki László Intézet – KSH Népszámlálás – KSH Levéltár, Budapest, 2005, ISBN 963-218-661-3

- "Rising speed – Audi in Győr and Suzuki in Esztergom to produce new models as from this summer". Budapest Telegraph. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "CLIMATE: ESZTERGOM". CLIMATE DATA.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). p. 971.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). p. 230.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). pp. 922–923.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). pp. 882–883.

- "Testvérvárosok". esztergom.hu (in Hungarian). Esztergom. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. p. 44.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 803.

- Official website in Hungarian, English, German and Slovak

- Aerial photography: Esztergom (Part 1) (Part 2)

- Basilica of Esztergom

- The Organ of The Esztergom Cathedral

- Keresztény Múzeum (Christian Museum)

- Szeretgom.hu - Online community portal, news, politics and cultural events in Esztergom (in Hungarian)