Ethiopian Civil War

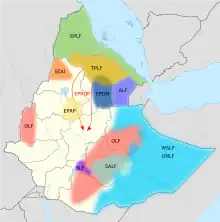

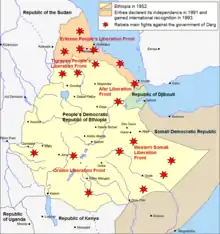

The Ethiopian Civil War was a civil war in Ethiopia and present-day Eritrea, fought between the Ethiopian military junta known as the Derg and Ethiopian-Eritrean anti-government rebels from 12 September 1974 to 28 May 1991.

| Ethiopian Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eritrean War of Independence, the Ethiopian–Somali conflict, the Oromo conflict and the Cold War | |||||||||

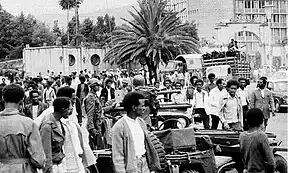

Clockwise from top: Public demonstration amid the Ethiopian Revolution; T-62 tank destroyed shortly after the fall of the Derg; Red Terror victims' skull remains at "Red Terror" Martyrs' Memorial Museum in Addis Ababa; The Somali Armed Forces conducting military parade before Ogaden War; Haile Selassie being deposed in the 1974 coup d'état | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Casualties and impact of the Ethiopian Civil War | |||||||||

|

~400,000–579,000 killed[13][14][15] ~1,200,000 deaths from famine[13][14][16] | |||||||||

| History of Ethiopia |

|---|

|

| History of Eritrea |

|---|

|

|

|

The Derg overthrew the Ethiopian Empire and Emperor Haile Selassie in a coup d'état on 12 September 1974, establishing Ethiopia as a Marxist-Leninist state under a military junta and provisional government. Various opposition groups of ideological affiliations ranging from Communist to anti-Communist, often drawn from a specific ethnic background, began armed resistance to the Soviet-backed Derg, in addition to the Eritrean separatists already fighting in the Eritrean War of Independence. The Derg used military campaigns and the Qey Shibir (Ethiopian Red Terror) to repress the rebels. By the mid-1980s, various issues such as the 1983–1985 famine, economic decline, and other after-effects of Derg policies ravaged Ethiopia, increasing popular support for the rebels. The Derg dissolved itself in 1987, establishing the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) under the Workers' Party of Ethiopia (WPE) in an attempt to maintain its rule. The Soviet Union began ending its support for the PDRE in the late-1980s and the government was overwhelmed by the increasingly victorious rebel groups. In May 1991, the PDRE was defeated in Eritrea and President Mengistu Haile Mariam fled the country. The Ethiopian Civil War ended on 28 May 1991 when the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of left-wing ethnic rebel groups, entered the capital Addis Ababa. The PDRE was dissolved and replaced with the Tigray People's Liberation Front-led Transitional Government of Ethiopia.[17]

The Ethiopian Civil War left at least 1.4 million people dead, with 1 million of the deaths being related to famine and the remainder from combat and other violence.

Background

The Ethiopian Empire became politically unstable beginning in the 1960s under the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie, whose administration was becoming very unpopular among ordinary Ethiopians at all levels of society due to stagnating quality of life, slow economic development and human rights abuses. Although Selassie had been a popular cultural figure with his attempts at modernizing Ethiopia, his reforms were ineffective. His rule was increasingly viewed as maintaining Ethiopia's feudal political system that heavily favored the Ethiopian nobility, who had routinely rejected his reforms. In December 1960, a group of high-ranking politicians and military officers attempted to overthrow Haile Selassie and institute a progressive government under his son, Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen, to solve Ethiopia's economic and political problems. However, the coup was crushed and quickly defeated by the loyalists, thus maintaining the status quo.

History

Ethiopian Revolution

On 12 September 1974, Haile Selassie and his government were overthrown by the Derg, a non-ideological committee of low-ranking officers and enlisted men in the Ethiopian Army who became the ruling military junta. On 21 March 1975, the Derg abolished the monarchy and adopted Marxism–Leninism as their official ideology, establishing themselves as a provisional government for the process of building a socialist state in Ethiopia. The Crown Prince went into exile in London, where several other members of the House of Solomon lived, while other members who were in Ethiopia at the time of the revolution were imprisoned. Haile Selassie, his daughter by his first marriage Princess Ijigayehu, his sister Princess Tenagnework, and many of his nephews, nieces, close relatives, and in-laws were among those detained. On 27 August 1975, Haile Selassie died under mysterious circumstances in detention at the National Palace in Addis Ababa.[18][19] That year, most industries and private urban real estate holdings were nationalized by the Derg regime. The assets of the former royal family were all seized and were nationalized in a program designed to implement the state ideology of socialism.

Ethiopian Red Terror

The Derg did not fully establish their control over the country, and the subsequent power vacuum led to open challenges from numerous civilian opposition groups. The Ethiopian government had been fighting Eritrean separatists in the Eritrean War of Independence since 1961, and now faced other rebel groups ranging from the conservative and pro-monarchy Ethiopian Democratic Union (EDU), to the rival Marxist-Leninist Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP), and the ethnic Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF). In 1976, the Derg instigated the Qey Shibir (Ethiopian Red Terror), a campaign of violent political repression primarily targeting the EPRP and later the All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON), in an attempt to consolidate their power. The Qey Shibir was escalated on 3 February 1977 following the appointment of Mengistu Haile Mariam as Chairman of the Derg, who took a hardline stance against opponents. The urban guerrilla warfare saw brutal tactics used on all sides, including summary executions, assassinations, torture and imprisonment without trial. By August 1977, the EPRP and MEISON were devastated, with their leadership either dead or fleeing to the countryside to continue their activities in stronghold areas, but despite this, the Derg did not successfully consolidate their power as much as hoped. Ironically, the majority of the Qey Shibir's estimated 30,000 to 750,000 victims are believed to be innocents, with the violence and collateral damage shocking many Ethiopians into supporting rebel groups. There are currently many civilians who are still missing who are thought to have been systematically killed by the Derg but are yet unaccounted for.

Ogaden War

On 13 July 1977, the Ogaden War was triggered when the Somali Democratic Republic invaded Ethiopia to annex the Ogaden and former Reserve area, a predominantly Somali populated border region. A month earlier, Mengistu accused Somalia of infiltrating Somali National Army (SNA) soldiers into the Ogaden to fight alongside the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), and despite considerable evidence to the contrary, Somalia's leader Siad Barre strongly denied this by stating SNA "volunteers" were being allowed to help the WSLF. Although both countries were Soviet-backed communist states, Barre sought to exploit Ethiopia's weakness since the 1974 revolution to incorporate the Ogaden on a platform of Somali nationalism and pan-Somalism. Under the Derg, Ethiopia became the Warsaw Pact's closest ally in Africa and one of the best-armed nations of the region as a result of military aid, chiefly from the Soviet Union, Libya, East Germany, Israel, Cuba and North Korea. The Ethiopians were able to defeat the Somali army by March 1978, though only with massive military assistance from the Soviet Union and Cuba, but the war used up valuable resources.

1980s

The Derg in its attempt to introduce full-fledged socialist ideals, fulfilled its main slogan of "Land to the Tiller", by redistributing land in Ethiopia that once belonged to landlords to the peasants tilling the land. Although this was made to seem like a fair and just redistribution, the mismanagement, corruption, and general hostility to the Derg's violent and harsh rule coupled with the draining effects of constant warfare, separatist guerrilla movements in Eritrea and Tigray, resulted in a drastic decline in general productivity of food and cash crops. Although Ethiopia is often prone to chronic droughts, no one was prepared for the scale of drought and the 1983–1985 famine that struck the country in the mid-1980s, in which 400,000–590,000 people are estimated to have died.[20] Hundreds of thousands fled economic misery, conscription and political repression, and went to live in neighboring countries and all over the Western world, creating an Ethiopian diaspora community for the first time in its history. Insurrections against the Derg's rule sprang up with ferocity, particularly in the northern regions of Tigray and Eritrea which sought independence and in some regions in the Ogaden. Hundreds of thousands were killed as a result of the Qey Shibir, forced deportations . The Derg continued its attempts to end rebellions with military force by initiating several campaigns against both internal rebels and the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF), the most important ones being Operation Shiraro, Operation Lash, Operation Red Star, and Operation Adwa, which led to its decisive defeat in the Battle of Shire on 15–19 February 1989 which ultimately led to Eritrean independence. This marked a receding end in power to the Derg.

1990s

In May 1991, Mengistu's government was overthrown by its own officials and a coalition of rebel forces, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), after their bid for a push on the capital Addis Ababa became successful. There was some fear that Mengistu would attempt to fight to the bitter end for the capital, but after diplomatic intervention by the United States, he fled to asylum in Zimbabwe, where he still resides.[21] The regime only survived another week after his ousting before the EPRDF poured into the capital and captured Addis Ababa.

The EPRDF immediately disbanded the Workers' Party of Ethiopia and shortly afterward arrested almost all of the most prominent Derg officials that were still in the country. In December 2006, 72 officials of the Derg were found guilty of genocide.[22] Thirty-four people were in court, 14 others died during the lengthy process and 25, including Mengistu, were tried in absentia.[23] These events marked the end of socialist rule in Ethiopia. Ethiopia then embraced a federal democracy to represent the many ethnic groups living in the country.

Peasant revolution in Ethiopia

There is not much in-depth information available about the revolution, but the book Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia by John Young provides detailed information about the revolution, why it started, how the Derg affected the nation, and the role of the peasant population in Tigray and Eritrea.

Casualties and impacts

.jpg.webp)

The Ethiopian Civil War left at least 1.4 million people dead, with 1 million related to famine and the remainder from violence and conflicts, which is one third of population.[24][25] It has also impacts on land and agriculture as well the reversal of former feudal system and implementation of nationalized reforms led peasants lost 75% production to landlords.[26] Total forest cover in Wollo Province was approximately 2.2% of the total area in 1980, and in Tigray 0.5%, roughly 50% decline since 1960. Soil erosion typically the topsoil roughly 100 tons per hectare per year. The erosion could halt grain production by 120,000 tons per year in Wollo Province.[27]

During the first six years, food production also increased by 6%. Crop production declined by 12.2% per year from 1982 to 1984. With the 1983–1985 famine, ten million people were affected five times of the 1973 drought.[26]

List of major battles

- 1974 Battle of Tirro

- 1977 First Battle of Massawa

- 1977 Siege of Barentu

- 1977–1978 Battle of Jijiga

- 1978 Battle of Harar

- 1988 Battle of Afabet, 17–20 March

- 1988 Battle of Shire (1989), 28 December 1988 – 19 February 1989

- 1990 Second Battle of Massawa, 8–10 February

See also

References

- "Ethiopia: Crackdown in East Punishes Civilians". 3 July 2007.

- Africa, United States Congress House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on (27 May 1992). The Political Crisis in Ethiopia and the Role of the United States: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Africa of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, First Session, June 18, 1991. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160372056 – via Google Books.

- Spencer C. Tucker, A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, 2009. page 2402

- Historical Dictionary of Eritrea, 2010. Page 492

- Oil, Power and Politics: Conflict of Asian and African Studies, 1975. Page 97.

- Ciment, James (27 March 2015). Encyclopedia of Conflicts Since World War II. Routledge. ISBN 9781317471868.

- Keneally, Thomas (27 September 1987). "IN ERITREA". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ""Wir haben euch Waffen und Brot geschickt"". Der Spiegel. 2 March 1980 – via www.spiegel.de.

- "Attempts to distort history". www.shaebia.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- "Ethiopia-Israel". country-data.com. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Eritrea (01/06)".

- Schmid & Jongman, 2005: 538-539.

- A Victory Tempered By Sorrow, Carlos Sanchez, Washington Post, May 26, 1991

- Mengistu Leaves Ethiopia in Shambles, Neil Henry, Washington Post, May 22, 1991

- Fifty Years of Violent War Deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia. Ziad Obermeyer, British Medical Journal (2008)

- Knives Are Out For A Bloodstained Ruler, Louis Rapoport, Sydney Morning Herald (from The New Republic) April 28, 1990.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2004). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-8014-3965-5.

- Reuters (22 May 1988). "Ethiopia Frees 7 Relatives of Haile Selassie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Perlez, Jane (3 September 1989). "Ethiopia Releases Prisoners From Haile Selassie's Family". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- De Waal, Alexander (1991). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch. p. 175. ISBN 9781564320384. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Ethiopia: Uncle Sam Steps In", Time 27 May 1991. (accessed 14 May 2009)

- Bloomfield, Steve (13 December 2006). "Mengistu found guilty of Ethiopian genocide". The Independent. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- "BBC NEWS | Africa | Mengistu found guilty of genocide". news.bbc.co.uk. 12 December 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Millward, Steve (20 April 2016). Fast Forward: Music And Politics In 1974. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78589-158-8.

- "EVIL DAYS - Human Rights Watch" (PDF). 20 August 2022.

- Gupta, Vijay (1978). "The Ethiopian Revolution: Causes and Results". India Quarterly. 34 (2): 158–174. doi:10.1177/097492847803400203. ISSN 0974-9284. JSTOR 45071379. S2CID 150699038.

- Lanz, Tobias J. (1996). "Environmental Degradation and Social Conflict in the Northern Highlands of Ethiopia: The Case of Tigray and Wollo Provinces". Africa Today. 43 (2): 157–182. ISSN 0001-9887. JSTOR 4187094.

Further reading

- De Waal, Alex (1991). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 9781564320384.

- Hammond, Jenny (1999). Fire from the ashes: a chronicle of the revolution in Tigray, Ethiopia, 1975 - 1991 (1. print ed.). Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-086-9.

- Young, John (1997). Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59198-8.

.jpg.webp)