Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid

Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA, icosapent ethyl), sold under the brand name Vascepa among others, is a medication used to treat dyslipidemia[4] and hypertriglyceridemia.[3] It is used in combination with changes in diet in adults with hypertriglyceridemia ≥ 150 mg/dL. Further, it is often required to be used with a statin (maximally-tolerated dose).[6]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vascepa, Vazkepa |

| Other names | Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester; Ethyl eicosapentaenoate; Eicosapent; EPA ethyl ester; E-EPA, Icosapent ethyl (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a613024 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Antilipemic Agents |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H34O2 |

| Molar mass | 330.512 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

The most common side effects are musculoskeletal pain, peripheral edema (swelling of legs and hands), atrial fibrillation, and arthralgia (joint pain).[6] Other common side effects include bleeding, constipation, gout, and rash.[4]

It is made from the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA).[6] The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted the approval of icosapent ethyl in 2012 to Amarin Corporation, and it became the second fish oil-based medication after omega-3-acid ethyl esters (brand named Lovaza, itself approved in 2004).[7] On 13 December 2019, the FDA also approved Vascepa as the first drug specifically "to reduce cardiovascular risk among people with elevated triglyceride levels".[6] It is available as a generic medication.[8] In 2020, it was the 285th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

In the European Union, icosapent ethyl is indicated to reduce cardiovascular risk as an adjunct to statin therapy.[4]

In the United States, icosapent ethyl is indicated as an adjunct to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, and unstable angina requiring hospitalization in adults with elevated triglyceride levels (≥ 150 mg/dL) and established cardiovascular disease or diabetes and two or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[3] It is also indicated as an adjunct to diet to reduce triglyceride levels in adults with severe (≥ 500 mg/dL) hypertriglyceridemia.[3]

Intake of large doses (2.0 to 4.0 g/day) of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids as prescription drugs or dietary supplements are generally required to achieve significant (> 15%) lowering of triglycerides, and at those doses the effects can be significant (from 20% to 35% and even up to 45% in individuals with levels greater that 500 mg/dL). It appears that both eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) lower triglycerides, however, DHA alone appears to raise low-density lipoprotein (the variant which drives atherosclerosis; sometimes very inaccurately called "bad cholesterol") and LDL-C values (most typically only a calculated estimate and not measured by labs from person's blood sample for technical and cost reasons; however, this is accurately calculated with a less common NMR lipid panel lab), whilst eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) alone does not and instead lowers the parameters aforementioned.[11]

Other fish-oil based drugs

There are other omega-3 fish-oil based drugs on the market that have similar uses and mechanisms of action:[12][7][13]

- Omega-3-acid ethyl esters (brand names Omacor [renamed Lovaza in the U.S. to avoid confusion with Amicar and Omtryg]),[14][15] and as of March 2016, four generic versions[16][17]

- Omega-3 carboxylic acids (Epanova);[18][19] the Epanova brand name was discontinued in the United States.[20]

Dietary supplements

There are many fish oil dietary supplements on the market.[7] Evidence suggests that marine based omega-3 dietary supplements are able to reduce cardiovascular disease,[21] and premature death.[22] Although these effects may not carry over in other populations such as people who have diabetes.[23][24][25] The ingredients of dietary supplements are not as carefully controlled as prescription products and have not been fixed and tested in clinical trials, as prescription drugs have,[26] and the prescription forms are more concentrated, requiring fewer capsules to be taken and increasing the likelihood of compliance.[7]

Side effects

Special caution should be taken with people who have fish and shellfish allergies.[3] In addition, as with other omega-3 fatty acids, taking ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) puts people who are on anticoagulants at risk for prolonged bleeding time.[3][11] The most commonly reported side effect in clinical trials has been joint pain; some people also reported pain in their mouth or throat.[3] E-EPA has not been tested in pregnant women;[27] it is excreted in breast milk and the effects on infants are not known.[3]

Pharmacology

After ingestion, ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) is metabolized to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). EPA is absorbed in the small intestine and enters circulation. Peak plasma concentration occurs about five hours after ingestion, and the half-life is about 89 hours. EPA is lipolyzed mostly in the liver.[3]

Mechanism of action

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), the active metabolite of ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA), like other omega-3 fatty acid based drugs, appears to reduce production of triglycerides in the liver and to enhance clearance of triglycerides from circulating very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles. The way it does that is not clear, but potential mechanisms include increased breakdown of fatty acids; inhibition of diglyceride acyltransferase, which is involved in biosynthesis of triglycerides in the liver; and increased activity of lipoprotein lipase in blood.[3][12]

Chemistry

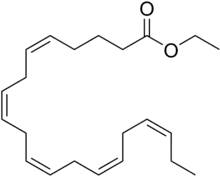

Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) is an ethyl ester of eicosapentaenoic acid, which is an omega-3 fatty acid.[3]

History

In July 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) for severe hypertriglyceridemia as an adjunct to dietary measures;[28] Amarin Corporation had developed the drug.[29] Amarin Corporation challenged the FDA's authority to limit its ability to market the drug for off-label use and won its case on appeal in 2012, changing the way the FDA regulates the marketing of medication.[30]

Ethyl eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) was the second fish-oil drug to be approved, after omega-3-acid ethyl esters (GlaxoSmithKline's Lovaza, which was approved in 2004.[31][7][32]) Initial sales were not as robust as Amarin had hoped. The labels for the two drugs were similar, but doctors prescribed Lovaza for people who had triglycerides lower than 500 mg/dL based on some clinical evidence. Amarin wanted to actively market E-EPA for that population as well which would have greatly expanded its revenue and applied to the FDA for permission to do so in 2013, which the FDA denied.[33] In response, in May 2015 Amarin sued the FDA for infringing its First Amendment rights,[34] and in August 2015, a judge ruled that the FDA could not "prohibit the truthful promotion of a drug for unapproved uses because doing so would violate the protection of free speech."[35] The ruling left open the question of what the FDA would allow Amarin to say about E-EPA, and in March 2016 the FDA and Amarin agreed that Amarin would submit specific marketing material to the FDA for the FDA to review (as is usual for prescription medications). If the parties disagreed on whether the material was truthful, they would seek a judge to mediate.[36]

In December 2019, the FDA approved the use of icosapent ethyl as an adjunctive (secondary) therapy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events among adults with elevated triglyceride levels (a type of fat in the blood) of 150 milligrams per deciliter or higher.[6] People must also have either established cardiovascular disease alone or diabetes along with two or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[6]

Icosapent ethyl is the first FDA approved drug to reduce cardiovascular risk among people with elevated triglyceride levels as an add-on to maximally tolerated statin therapy.[6]

The efficacy and safety of icosapent ethyl were established in a study with 8,179 participants who were either 45 years and older with a documented history of coronary artery, cerebrovascular, carotid artery and peripheral artery disease or 50 years and older with diabetes and additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[6] Participants who received icosapent ethyl were significantly less likely to experience a cardiovascular event, such as a stroke or heart attack.[6]

In clinical trials, icosapent ethyl was associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (irregular heart rhythms) requiring hospitalization.[6] The incidence of atrial fibrillation was greater among participants with a history of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.[6] Icosapent ethyl was also associated with an increased risk of bleeding events.[6] The incidence of bleeding was higher among participants who were also taking other medications that increase the risk of bleeding, such as aspirin, clopidogrel or warfarin at the same time.[6]

Society and culture

Legal status

On 28 January 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Vazkepa, intended to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people at high cardiovascular risk.[37] The applicant for this medicinal product is Amarin Pharmaceuticals Ireland Limited.[37] It was approved for medical use in the European Union in March 2021.[4]

References

- "Vazkepa". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 22 November 2022. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Vascepa". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- "Vascepa- icosapent ethyl capsule". DailyMed. 23 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Vazkepa EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 25 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- "Vazkepa Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "FDA approves use of drug to reduce risk of cardiovascular events in certain adult patient groups". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Ito MK (December 2015). "A Comparative Overview of Prescription Omega-3 Fatty Acid Products". P & T. 40 (12): 826–857. PMC 4671468. PMID 26681905. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Icosapent ethyl: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- "Icosapent Ethyl - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Jacobson TA, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Jones PH, Kris-Etherton P, Sikand G, et al. (2015). "National Lipid Association Recommendations for Patient-Centered Management of Dyslipidemia: Part 2". Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 9 (6 Suppl): S1–122.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2015.09.002. PMID 26699442.

- Weintraub HS (November 2014). "Overview of prescription omega-3 fatty acid products for hypertriglyceridemia". Postgraduate Medicine. 126 (7): 7–18. doi:10.3810/pgm.2014.11.2828. PMID 25387209. S2CID 12524547.

- Brinton EA, Mason RP (January 2017). "Prescription omega-3 fatty acid products containing highly purified eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)". Lipids Health Dis. 16 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/s12944-017-0415-8. PMC 5282870. PMID 28137294.

- "University of Utah Pharmacy Services (15 August 2007) "Omega-3-acid Ethyl Esters Brand Name Changed from Omacor to Lovaza"". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Omtryg- omega-3-acid ethyl esters capsule". DailyMed. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- FDA Omega-3 acid ethyl esters products Page accessed 31 March 2016 Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Omega-3-acid ethyl esters". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Epanova (omega-3-carboxylic acids)". CenterWatch. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Drug Approval Package: Epanova (Omega-3-carboxylic acids)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Epanova (omega-3-carboxylic acids) FDA Approval History". Drugs.com. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Hu Y, Hu FB, Manson JE (October 2019). "Marine Omega-3 Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis of 13 Randomized Controlled Trials Involving 127 477 Participants". Journal of the American Heart Association. 8 (19): e013543. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.013543. PMC 6806028. PMID 31567003.

- Harris WS, Tintle NL, Imamura F, Qian F, Korat AV, Marklund M, et al. (April 2021). "Blood n-3 fatty acid levels and total and cause-specific mortality from 17 prospective studies". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 2329. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22370-2. PMC 8062567. PMID 33888689.

- American Diabetes Association (January 2020). "5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020". Diabetes Care. American Diabetes Association. 43 (Suppl 1): S48–S65. doi:10.2337/dc20-S005. PMID 31862748.

- Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. (April 2017). "American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease". Endocrine Practice. AACECOR. 23 (Suppl 2): 1–87. doi:10.4158/EP171764.APPGL. PMID 28437620.

- Skulas-Ray AC, Wilson PW, Harris WS, Brinton EA, Kris-Etherton PM, Richter CK, et al. (September 2019). "Omega-3 Fatty Acids for the Management of Hypertriglyceridemia: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 140 (12): e673–e691. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000709. PMID 31422671.

- Sweeney ME (14 April 2015). Khardori R (ed.). "Hypertriglyceridemia Pharmacologic Therapy". Medscape Drugs & Diseases. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- "Icosapent (Vascepa) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- "Drug Approval Package: Vascepa (icosapent ethyl) NDA #202057". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- CenterWatch Vascepa (icosapent ethyl) Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed 31 March 2016

- Mariani E (28 March 2016). "Health Law Case Brief: Amarin Pharma, Inc. v. FDA". Boston Bar Association. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- "Drug Approval Package: Omacor (Omega-3-Acid Ethyl Esters) NDA #021654". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- VHA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group and the Medical Advisory Panel. October 2005 National PBM Drug Monograph Omega-3-acid ethyl esters (Lovaza, formerly Omacor) Archived 22 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Herper M (17 October 2013). "Why The FDA Is Right To Block Amarin's Push To Market Fish Oil To Millions". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Thomas K (7 May 2015). "Drugmaker Sues F.D.A. Over Right to Discuss Off-Label Uses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Pollack A (7 August 2015). "Court Forbids F.D.A. From Blocking Truthful Promotion of Drug". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Thomas K (9 March 2016). "F.D.A. Deal Allows Amarin to Promote Drug for Off-Label Use". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- "Vazkepa: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.