White Brazilians

White Brazilians (Portuguese: brasileiros brancos [bɾaziˈle(j)ɾuz ˈbɾɐ̃kus]) refers to Brazilian citizens who are considered or self-identify as "white", typically because of European or Levantine descent.

Brasileiros brancos | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) White Brazilians in São Paulo | |

| Total population | |

| 91,051,646 47.7% of the Brazilian population (2010 Census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Entire country; highest percentages found in the South Region and Southeast Region[2] | |

| 27,229,000 | |

| 9,251,000 | |

| 8,937,000 | |

| 7,828,000 | |

| 7,591,000 | |

| 5,971,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Mostly Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Catholic Church 66.4% Minority: Protestantism 20.8%, Irreligion 6.7%, Spiritism 2.9%, Other (Jehovah's Witnesses, Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Umbanda) 3.0%[3] | |

The main ancestry of current white Brazilians is Portuguese.[4] Historically, the Portuguese were the Europeans who mostly immigrated to Brazil: it is estimated that, between 1500 and 1808, 500,000 of them went to live in Brazil,[5] and the Portuguese were practically the only European group to have definitively settled in colonial Brazil.

Furthermore, even after independence, the Portuguese were among the nationalities that mostly immigrated to Brazil.[5] Between 1884 and 1959, 4,734,494 immigrants entered Brazil, mostly from Portugal and Italy, but also from Spain, Germany, Poland and other countries[6] and nowadays millions of Brazilians are also descended from these immigrants.[7]

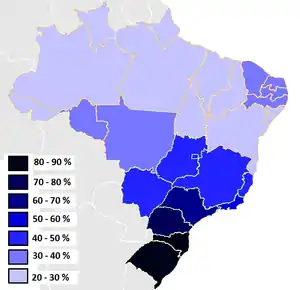

The white Brazilian population is spread throughout Brazil's territory, but its highest percentage is found in the three southernmost states, where 79.8% of the population claims to be White in the censuses, whereas the Southeast region has the largest absolute numbers.[8]

According to the 2010 Census, the states with the highest percentage of white citizens are: Santa Catarina (88.1%), Rio Grande do Sul (82.3%), Paraná (70.06%), and São Paulo (63.65%). Other states with significant rates are: Rio de Janeiro (54.7%), Mato Grosso do Sul (51.78%) and Espírito Santo (50.45%). São Paulo has the largest population in absolute numbers with 29 million whites.[2]

Conception of "white" in Brazil

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The conception of "white" in Brazil is similar to other Latin American countries yet different to the United States, where historically only people of entirely or (almost entirely) European ancestry have been considered white, due to the one drop rule.[9] In Brazil and in Latin America in general, this conception does not exist. A 2000 survey conducted in Rio de Janeiro concluded that "racial-purity" is not important for a person to be classified as white in Brazil. The survey asked respondents if they had any ancestors who were European, African or Amerindian. As much as 52% of those whites reported they have some non-European ancestry: 25% reported to have some African ancestry and 14% reported Amerindian ancestry (15% of them reported to have both). Only 48% of those whites did not report any non-European ancestry. Thus, in Brazil, one can self-identify as "white" and still have African or Amerindian ancestry, and such a person has no problem admitting to having non-European ancestors.[9]

| Ancestry | Percentage |

|---|---|

| European only | 48% |

| European and African | 25% |

| European, African and Amerindian | 15% |

| European and Amerindian | 14% |

In colonial Brazil, the formation of a white population of exclusive European ancestry was not very common. In the first centuries of colonization, almost only Portuguese men immigrated to Brazil, since Portuguese women were often prevented from migrating. Given such gender imbalance, Portuguese male settlers often had relationships with Amerindian or African women, what led to an extremely mixed population.[9]

At the end of the 19th century, when eugenic ideas arrived in Brazil, a severe racial segregation, similar to that of the United States or South Africa, that separated "whites" from "non-whites", was regarded as impractical in Brazil, since this would even exclude many members of the Brazilian elite.[9] Thus, in Brazil, racial classifications are more flexible and based primarily on a person's physical characteristics, such as skin color, hair type and other physical traits, tending to identify as "white" a person with lighter skin color.[9]

In Brazil, social prejudice connected to certain details in the physical appearance of individual is widespread. Those details are related to the concept of "cor". "Cor", Portuguese for "color", denotes the Brazilian rough equivalent of the term "race" in English, but is based on a complex phenotypic evaluation that takes into account skin pigmentation, hair type, nose shape, and lip shape. This concept, unlike the English notion of "race", captures the continuous aspects of phenotypes. Thus, it seems there is no racial descent rule operational in Brazil; it is even possible for two siblings to belong to completely diverse "racial" categories.[10]

An important factor about whiteness in Brazil is the racial stigma of being Amerindian or Black, which is undesirable and avoided for a large part of the population.[11] Scientific racism largely influenced race relations in Brazil since the late 19th century.[9] The predominant non-white, mostly Afro-Brazilian population was seen as a problem for Brazil in the eyes of the predominantly white elite of the country. In contrast to some countries, like the United States or South Africa, which tried to avoid miscegenation, even imposing anti-miscegenation laws, in Brazil miscegenation was always legal. What was expected was that miscegenation would eventually turn all Brazilians into whites.[9] However, the most recent census in 2010 showed a shift in mentality, with a growing number of Brazilians identifying themselves as brown or Black, accompanied by a decrease in the percentage of whites,[12] with affirmative action and identity valorisation being factors.[13]

As a result of that desire of whitening its own population, the Brazilian ruling classes encouraged the arrival of massive European immigration to the country. In the 1890s, 1.2 million European immigrants were added to the country's 5 million whites. Today the Brazilian areas with larger proportions of whites tend to have been destinations of massive European immigration between 1880 and 1930.[9]

The following are the results for the different Brazilian censuses, since 1872:

| Race or Color | Brancos ("whites") | Pardos ("mixed") | Pretos ("blacks") | Caboclos ("indigenous"/ | Amarelos ("yellow"/ | Indigenous | Undeclared | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18722 | 3,787,289 | 3,801,782 | 1,954,452 | 386,955 | - | - | - | 9,930,478 |

| 1890 | 6,302,198 | 4,638,4963 | 2,097,426 | 1,295,7953 | - | - | - | 14,333,915 |

| 1940 | 26,171,778 | 8,744,3654 | 6,035,869 | - | 242,320 | - | 41,983 | 41,236,315 |

| 1950 | 32,027,661 | 13,786,742 | 5,692,657 | - | 329,082 | -5 | 108,255 | 51,944,397 |

| 1960 | 42,838,639 | 20,706,431 | 6,116,848 | - | 482,848 | -6 | 46,604 | 70,191,370 |

| 1980 | 64,540,467 | 46,233,531 | 7,046,906 | - | 672,251 | - | 517,897 | 119,011,052 |

| 1991[14] | 75,704,927 | 62,316,064 | 7,335,136 | - | 630,656 | 294,135 | 534,878 | 146,815,796 |

| 2000[15] | 91,298,042 | 65,318,092 | 10,554,336 | - | 761,583 | 734,127 | 1,206,675 | 169,872,856 |

| 2010[16] | 91,051,646 | 82,277,333 | 14,517,961 | - | 2,084,288 | 817,963 | 6,608 | 190,755,799 |

| Race or Color | Brancos | Pardos | Pretos | Caboclos | Amarelos | Indigenous | Undeclared | Total |

| 1872 | 38.14% | 38.28% | 19.68% | 3.90% | - | - | - | 100% |

| 1890 | 43.97% | 32.36% | 14.63% | 9.04% | - | - | - | 100% |

| 1940 | 63.47% | 21.21% | 14.64% | - | 0.59% | - | 0.10% | 100% |

| 1950 | 61.66% | 26.54% | 10.96% | - | 0.63% | - | 0.21% | 100% |

| 1960 | 61.03% | 29.50% | 8.71% | - | 0.69% | - | 0.07% | 100% |

| 1980 | 54.23% | 38.85% | 5.92% | - | 0.56% | - | 0.44% | 100% |

| 1991 | 51.56% | 42.45% | 5.00% | - | 0.43% | 0.20% | 0.36% | 100% |

| 2000 | 53.74% | 38.45% | 6.21% | - | 0.45% | 0.43% | 0.71% | 100% |

| 2010 | 47.73% | 43.13% | 7.61% | - | 1.09% | 0.43% | 0.00% | 100% |

^1 The 1900, 1920, and 1970 censuses did not count people for "race".

^2 In the 1872 census, people were counted based on self-declaration, except for slaves, who were classified by their owners.[17]

^3 The 1872 and 1890 censuses counted "caboclos" (White-Amerindian mixed race people) apart.[18] In the 1890 census, the category "pardo" was replaced with "mestiço".[18] Figures for 1890 are available at the IBGE site.[19]

^4 In the 1940 census, people were asked for their "color or race"; if the answer was not "White", "Black", or "Yellow", interviewers were instructed to fill the "color or race" box with a slash. These slashes were later totaled in the category "pardo". In practice this means answers such as "pardo", "moreno", "mulato", "caboclo", etc.[20]

^5 In the 1950 census, the category "pardo" was included on its own. Amerindians were counted as "pardos".[21]

^6 The 1960 census adopted a similar system, again explicitly including Amerindians as "pardos".[22]

History

Portuguese colonization

Brazil received more European settlers during its colonial era than any other country in the Americas. Between 1500 and 1760, about 700,000 Europeans immigrated to Brazil.[23]

In the first two centuries of colonization (16th and 17th centuries), it is estimated that no more than 100,000 Portuguese people migrated to Brazil. They were more affluent immigrants, who settled mainly in the captaincies of Pernambuco and Bahia, to explore sugar production, which was the most profitable activity in the colony at that time.[24][25] At the end of the 16th century, the white population (the vast majority Portuguese) was of over 30,000 people, mainly concentrated in the captaincies of Pernambuco, Bahia and São Vicente. The colonization process continued throughout the 17th century and by the end of the century, the white population was of nearly 100,000 people.[26]

.jpg.webp)

It is notable that most Portuguese settlers arrived in Brazil in the 18th century: 600,000 in a period of only sixty years. Initially unattractive during the first two centuries of colonization, as it concentrated sugar production, which required high investments, by the end of the 17th and in the beginning of the 18th centuries, due to the retreat of the Portuguese Empire in Asia and the discoveries of gold in the Brazilian region of Minas Gerais, there were more favorable conditions for the arrival of Portuguese immigrants in Brazil. There was no need for major investments for mining activity. Mining in these regions was a crucial factor in the arrival of this contingent of Portuguese immigrants.[27]

A characteristic of the Portuguese colonization is that it was predominantly male. Portuguese immigration to Brazil in the 16th and 17th centuries was made up almost exclusively of men. The typical Portuguese settler in Brazil was a young man in his late teens or in his early twenties, coming from the provinces of Northern Portugal, most notably Minho and Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, or from the Atlantic islands. White women of marriageable age were rare throughout the Portuguese maritime Empire. The few Portuguese families that immigrated to Brazil tended to stay on the coast, rarely penetrating the interior. The situation changed slightly in the 18th century, when the migration of families and women from the Azores and Madeira islands increased.[28]

In addition to the fact that marriageable Portuguese women who arrived in Brazil were rare, the few remaining white women often remained celibate, as it was a tradition among aristocratic or richer white families to send their daughters to Catholic convents, where they would follow a religious life.[28] Given this absence of white women available for marriage, it was inevitable for Portuguese colonists to take as a lover a woman of African or indigenous origin. The Portuguese Crown's concern about the scarcity of marriages among whites in the colony became evident in 1732, when John V of Portugal prohibited women from leaving Brazil, with some exceptions. In order to curb miscegenation, in a royal decree of 1726, the king demanded that all candidates for positions in the municipal councils of Minas Gerais had to be whites and husbands or widowers of white women. Restrictive measures like this, however, would not be able to restrict the natural tendency to miscegenation in colonial Brazil.[28]

Thus, the "white" population of colonial Brazil was not formed by the multiplication of European families in the colony, as occurred, for example, in the United States, but often by the miscegenation between European men and African or indigenous women, giving rise to a population defined as "white", but which was, to a greater or lesser degree, of mixed-race heritage. This population, speaking Portuguese and completely integrated with the "neo-Brazilian" culture, has assisted the Portuguese colonizers to impose their dominant characteristics in Brazil.[29]

Unidentified woman and baby in Rio de Janeiro, 1855.

Unidentified woman and baby in Rio de Janeiro, 1855. Portrait of Francisca "Chiquinha" in Rio de Janeiro, 1891

Portrait of Francisca "Chiquinha" in Rio de Janeiro, 1891 Unknown Brazilian family, 1880

Unknown Brazilian family, 1880 Unknown Brazilian girl, 1889

Unknown Brazilian girl, 1889 Unknown young Brazilian man, 1850

Unknown young Brazilian man, 1850 Unknown Brazilian family, 1860

Unknown Brazilian family, 1860 White man delivering a love letter to a mulatto woman

White man delivering a love letter to a mulatto woman Woman and man of colonial Brazil

Woman and man of colonial Brazil

The impact of the Portuguese colonization

.jpg.webp)

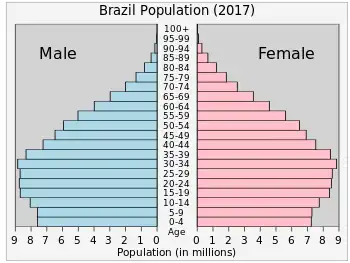

According to estimates of Brazil's ethnic composition in 1835 (excluding the indigenous peoples), just over half of the Brazilian population was black (51.4%), followed by whites (24.4%) and brown people (18.2%). About four decades later, in 1872, the census registered significant changes in the ethnic composition: blacks dropped to 19.7%, while whites increased their proportion to 38.1% and brown people became the most numerous, at 42.2%.[30]

| Year | White | Brown | Black |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1835 | 24.4% | 18.2% | 51.4% |

| 1872 | 38.1% | 42.2% | 19.7% |

The proportional reduction of blacks and the increase of whites and brown people, between 1835 and 1872, had little or nothing to do with a recent European immigration: between 1822 and 1872, only 268,000 European immigrants entered Brazil, and these immigrants and their descendants did not exceed 6% of the Brazilian population in 1872.[31] What explains this change is that the Portuguese colonizers and their descendants managed to reproduce much more quickly than Africans and their descendants. During the three centuries of African slavery in Brazil, the growth of the black population was basically due to the importation of new slaves from Africa, given that the natural reproduction of slaves was very slow and even little stimulated (it was more economical to buy new slaves than to take care of slave children). Moreover, life expectancy of slaves in Brazil was very low.[32][29] In the words of Augustin Saint-Hilaire: "An infinity of blacks died without leaving any descendants". In 1850, with the prohibition of the entry of new slaves in Brazil, the proportional growth of the black population not only stagnated, but also decreased substantially, as can be seen.[33]

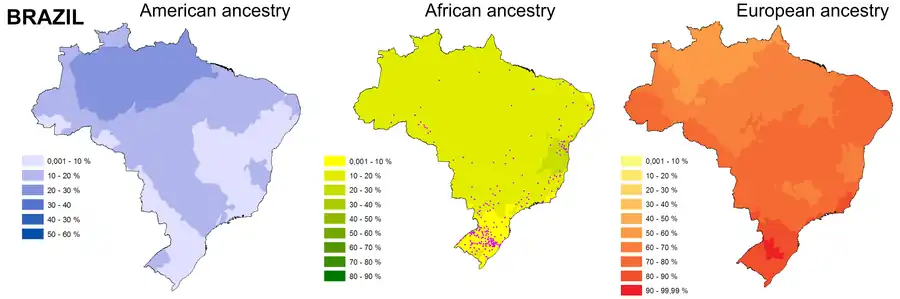

On the other hand, the Portuguese and their descendants managed to increase their numbers, year after year, not by the entry of new immigrants, but by their remarkable reproductive capacity, particularly through miscegenation with indigenous and black women, which explains the continuous growth of “whites” and mainly of "brown people" in the 19th century.[29] Genetic studies show that, even in Brazilian regions that received little or virtually no European immigration after independence from Portugal (such as the North and Northeast),[34] European genetic ancestry predominates in the population.[35] European ancestry is greater than the African or Amerindian ones in all regions of Brazil.[36]

This does not mean that the majority of the population in these regions is "white"; on the contrary, due to the high degree of miscegenation between Europeans, Africans and Amerindians, in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil only a minority is white, and the majority identify themselves as “brown” in the censuses;[37] however, the genetic composition of these regions, with a predominance of European ancestry, particularly Portuguese, highlights the genetic legacy inherited from Portuguese colonization and the complex miscegenation that occurred back then.[38]

| Region | European | African | Amerindian |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South | 77% | 12% | 11% |

| Brazil | 62% | 21% | 17% |

Non-Portuguese presence in colonial Brazil

Before the 19th century, the French invaded twice, establishing brief and minor settlements (Rio de Janeiro, 1555–60; Maranhão, 1612–15).[39] In 1630, the Dutch made the most significant attempt to seize Brazil from Portuguese control. At the time, Portugal was in a dynastic union with Spain, and the Dutch hostility against Spain was transferred to Portugal. The Dutch were able to control most of the Brazilian Northeast – then the most dynamic part of Brazil – for about a quarter century, but were unable to change the ethnic makeup of the colonizing population, which remained overwhelmingly Portuguese by origin and culture.[40] Sephardic Jews of Portuguese origin moved from Amsterdam to New Holland;[40] but in 1654, when the Portuguese regained control of Brazil, most of them were expelled, as well as most of the Dutch settlers.[41] A group of Dutch and Portuguese Jews then moved to North America, forming a Jewish community in New Amsterdam, today's New York city, while a few of the Dutch colonists settled in the highlands in the countryside of Pernambuco known as Borborema Plateau, a region part of the ecosystem known as agreste between the coastal forest zona da mata and the semiarid sertão in the Northeast.[42][43][44][45]

Aside these military attempts, a very small number of non-Portuguese people appear to have managed to enter Brazil from European countries other than Portugal.[46]

However, in the Southern Brazilian areas disputed between Portugal and Spain, Spanish colonists largely contributed for the ethnic formation of the local population, denominated Gaúchos. A genetic research conducted by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) on Gaúchos from Bagé and Alegrete, in Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil, revealed that they are mostly descended from Portuguese and Spanish ancestors, with 52% of them having Amerindian MtDNA (similar to that found in people who live in the area of the Amazon rainforest, and significantly higher than the national average – 33% – among Brazilian whites) and 11% African MtDNA.[47] Another study also concluded that for the formation of the Gaúcho there was a predominance of Iberians, particularly Spaniards.[48] To evaluate the extension of Gaucho genetic diversity of the Gauchos, and retrieve part of their history, a study with 547 individuals, of which 278 were Native Americans (Guarani and Kaingang) and 269 admixed from the state of Rio Grande do Sul, was carried out. The genetic finding matches with the explanation of sociologist Darcy Ribeiro about the ethnic formation of the Brazilian Gaúchos: they are mostly the result of the miscegenation of Spanish and Portuguese males with Amerindian females.[29]

Another genetic study found possible relics of the 17th-century Dutch invasion in Northeastern Brazil.[49]

Mass European immigration

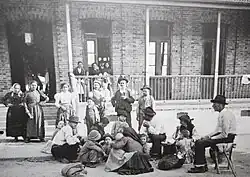

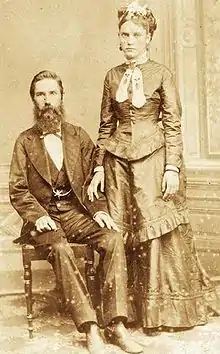

.jpg.webp)

The main immigrant group to arrive in Brazil from the end of the 19th century onwards were the Italians, and they went mainly to São Paulo. In the early days, immigrants from northern Italy predominated, especially from Veneto, however, at the end of the century, the southern presence grew, especially from Campania and Calabria. The Italians, pressured by the poverty that plagued Italy, headed for rural settlements in southern Brazil, where they became small farmers, as well as for coffee farms in the southeast, where they replaced slave labor. Others, especially the southern ones, went straight to urban centers.[50]

The second main group were the Portuguese who, added to the colonizing population of the earlier centuries, form the most important European group in Brazil. The fragmentation and disappearance of small properties in northern Portugal at the end of the 19th century stimulated a growing emigration to Brazil, which was seen by the Portuguese as a land of abundance and opportunities for enrichment. Of those who arrived, most headed for the city of Rio de Janeiro. Young immigrants who arrived supported by a pre-existing solidarity network represented 8 to 11% of immigrants; those qualified or possessing capital to invest in Brazil constituted about 10% of the total, while immigrants without any type of qualification made up no less than 80% of the Portuguese who arrived in Rio at the end of the 19th century.[51]

The third most numerous group came from Spain. Spaniards, often forgotten by Brazilian historiography, went mainly to São Paulo, to work in the coffee plantations. They were mainly from southern Spain, from the Andalusia region, although the flow from Galicia was also important.[52]

The fourth most relevant group were the Germans. The promotion of German immigration to Brazil was old, dating back to 1824, with the presence of immigrants who had a great importance in the occupation of southern Brazil. They founded rural communities, which later became prosperous cities, such as São Leopoldo, Joinville and Blumenau.[53]

It was only in 1818 that the Portuguese rulers abandoned the principle of restricting settling in Brazil to Portuguese nationals. In that year over two thousand Swiss migrants from the Canton of Fribourg arrived to settle in an inhospitable area near Rio de Janeiro that would later be renamed Nova Friburgo.[54]

The end of the slave trade (1850) and the abolition of slavery (1888) prompted the Brazilian State to promote European immigration to Brazil. The production of coffee, the main product of Brazil at the time, began to suffer a shortage of workers due to the slave emancipation process. In one hundred years (1872-1972) at least 5,350,889 immigrants came to Brazil, of whom 31.06% were Portuguese, 30.32% Italians, 13.38% Spaniards, 4.63% Japanese, 4.18% Germans and 16.42% of other unspecified nationalities. These immigrants settled mostly in the South and Southeast regions of Brazil.[34]

Brazilian scientific thought at the time, which was strongly marked by positivism, adopted "scientific theses" of social Darwinism and eugenics to defend the "whitening" of the population as a necessary factor for the development of Brazil. The Brazilian social and political elite, which was mostly white, took it for granted that the country did not develop because its population was largely composed of black and mixed-race people. Immigration was not only considered a means of supplying the necessary labor in the fields, or of colonizing the national territory covered by virgin forests, but also as a means of "improving" the Brazilian population by increasing the number of whites.[55] Hence, Brazilian immigration policies were strongly influenced by the racial whitening ideology that permeated the Brazilian social and political imaginary during the first half of the 20th century.[56]

South American oligarchies, which remained predominantly of European origin, believed – in syntony with the racialist theories then widespread in Europe – that the large numbers of blacks, Amerindians and mixed-race people who made up the majority of the population were a handicap to the development of their countries. As a result, countries such as Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil started to encourage the arrival of European immigrants, in order to make the white population grow and to dilute the African and Amerindian blood in their population. Argentina even had an article in its Constitution prohibiting any attempt to prevent the entry of European immigrants in the country.[57] In the case of Brazil, the immigrants started arriving in huge numbers during the 1880s. From 1886 to 1900, almost 1.4 million Europeans arrived, of whom over 900,000 were Italians. During this period of 14 years, Brazil received more Europeans than during the over 300 years of colonization.

The mass European immigration to Brazil only started in the second half of the 19th century, from 1850 to 1970 over 5 million Europeans arrived, because of three main reasons:[29]

- to "whiten" Brazil, since the Amerindian and African elements were very strong in the population, a fact that was considered a problem by the local elite, that considered these races inferior. Bringing European immigrants was seen as a way to "improve" the racial composition of the local population;

- to populate inhospitable areas of Brazil, mostly the Southern provinces;

- to replace African manpower, since the Atlantic slave trade was effectively suppressed in 1850 and coffee plantations were spreading in the region of São Paulo.

Brazilian coffee producers, fearful of the crisis in the labor force, began to put pressure on the Legislative Branch to facilitate the entry of foreign workers to be inserted as manpower in the coffee plantations. To this end, laws were enforced to facilitate the entry of immigrants and the Brazilian government started to spend public money paying the passage of immigrants from Europe. The state of São Paulo, in the first decade of the Republican Regime, allocated about 9% of its revenue to cover spending on promoting immigration.[58]

European immigrants were brought to Brazil mostly to replace the slave labor in coffee plantations. Brazilian landowners, who were used to deal with slaves, began to deal with free and paid European workers. These immigrants were often mistreated by Brazilian farmers and subjected to conditions of semi-slavery. The conditions were so harsh that, in 1902, the Italian government issued Prinetti Decree, which restricted the emigration of Italian citizens to Brazil, prohibiting travel subsidies.[50] In 1910, Spain banned subsidized immigration to Brazil, after complaints that Spanish citizens were living in conditions of semi-slavery in coffee plantations of Brazil.[59]

| Nationality | Decade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884-1893 | 1894-1903 | 1904-1913 | 1914-1923 | 1924-1933 | 1945-1949 | 1950-1954 | 1955-1959 | |

| Germans | 22,778 | 6,698 | 33,859 | 29,339 | 61,723 | 5,188 | 12,204 | 4,633 |

| Spaniards | 113,116 | 102,142 | 224,672 | 94,779 | 52,405 | 4,092 | 53,357 | 38,819 |

| Italians | 510,533 | 537,784 | 196,521 | 86,320 | 70,177 | 15,312 | 59,785 | 31,263 |

| Japanese | - | - | 11,868 | 20,398 | 110,191 | 12 | 5,447 | 28,819 |

| Portuguese | 170,621 | 155,542 | 384,672 | 201,252 | 233,650 | 26,268 | 123,082 | 96,811 |

| Middle Easterners | 96 | 7,124 | 45,803 | 20,400 | 20,400 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other | 66,524 | 42,820 | 109,222 | 51,493 | 164,586 | 29,552 | 84,851 | 47,599 |

| Total | 883,668 | 852,110 | 1,006,617 | 503,981 | 717,223 | 80,424 | 338,726 | 247,944 |

Impact of mass immigration

The immigration of millions of Europeans to Brazil, between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, contributed to bring greater diversity to the Brazilian population. It is estimated that about 20% of the Brazilian population is descended from people who immigrated to the country in that period,[31] and, in certain regions of the South and Southeast, this percentage is much higher.[7] In the regions where they concentrated most, these immigrants created Europeanized landscapes and bequeathed a dominantly "white" population, creating a human panorama different from the relative Portuguese-Brazilian uniformity of the country, but where it is possible to distinguish the sub-areas where each ethnic group was concentrated, whether German, Italian, Polish or Russian.[29]

The process of acculturation of these immigrants in the Brazilian society was highly variable from nationality to nationality. Portuguese, Italians and Spaniards assimilated more easily; Russians, Poles and Austrians occupied an intermediate position, while Germans were more resistant.[60]

The influence of the environment cannot be underestimated: immigrants who went to coffee farms or urban centers assimilated more easily, as there was daily contact with Brazilians, generating common interests, friendships and mixed marriages. In these regions, the Portuguese language quickly supplanted the languages of the immigrants, facilitating their process of acculturation.[60]

In turn, the immigrants who went to the rural settlements (colonies) were gathered in isolated groups, maintaining little contact with the rest of the Brazilian society, which allowed the maintenance of language and ethnic identity for generations. Until the 1940s, in the colonies, few descendants of immigrants knew how to speak Portuguese, even though some of them had been living in Brazil for generations. The big blow came through the nationalization campaign, implemented during Getúlio Vargas's dictatorship, starting in 1937. The Brazilian government started to see the immigrant colonies as a “national problem”, which threatened the uniformity of Brazilian identity, and their inhabitants were subject to great repression. Vargas ordered all schools associated with foreign cultures to be closed, forcing all schools to teach exclusively in Portuguese, and the use of foreign languages, including orally, in public or in private, was banned in Brazil, with people being arrested and beaten.[61][62][63][64]

Even with the repression of Vargas Estado Novo dictatorship, minority languages of European origin still survive in certain communities concentrated in southern Brazil, mainly of German, Italian and Slavic origin. However, their use has been decreasing in recent generations. The break with the isolation of these communities, with the improvement of highways and infrastructure, the need to learn Portuguese to enter the job market, as well as the diffusion of the media (press, radio, television, internet), has led to the growing use of the Portuguese language in these communities.[65][66][67][68]

Italian Brazilian girls in Caxias do Sul, 1934.

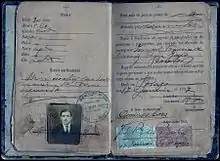

Italian Brazilian girls in Caxias do Sul, 1934. Ukrainian family in Brazil, 1891.

Ukrainian family in Brazil, 1891. Portuguese immigrant in Rio de Janeiro, 1895.

Portuguese immigrant in Rio de Janeiro, 1895. Italian family in Southern Brazil, 1901.

Italian family in Southern Brazil, 1901. Passport of a Portuguese immigrant, 1927.

Passport of a Portuguese immigrant, 1927.

European immigrants working in a coffee plantation in the State of São Paulo.

European immigrants working in a coffee plantation in the State of São Paulo.

Immigrants

Most of the 4,431,000 immigrants that entered the country between 1821 and 1932 settled in São Paulo (state) and other Southeastern states:[69] São Paulo received most of the Italians (Veneto, Lombardy, Campania, Tuscany, Calabria, Liguria, Piedmont, Umbria, Emilia-Romagna, Abruzzi e Molise and Basilicata) and Spaniards (Galicians, Castilians and Catalans) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and from the 1910s on most of the Lithuanians, Dutch, French, Hungarians, Baltic Finns, Ashkenazi Jews (from diaspora communities in Poland, Romania, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Lithuania, Russia and Czechoslovakia), Latvians, Greeks, Armenians, Czech, Croatians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Albanians and Georgians;[70][71][72][73][74][34][75][76][77][78][79][80] Rio de Janeiro (state) received most of the Portuguese immigrants followed by SP, as well as most of the Swiss and Belgians. Together with São Paulo and Santa Catarina, RJ was one of the main destinations for Swedes, Norwegians, Danes but also French and received the second largest number of Jews after SP. São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro followed by Paraná also received most of the English-Welsh and Scots;[72][34][81][82][83][84] The countryside of Espírito Santo was mainly populated by people arriving from Germany, especially Pomeranians (Prussia), Switzerland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Denmark, Luxembourg, France, Romania, Slovakia and Iberia, comprising chiefly Catalans but including Basques and Andorrans.[73][75][80][85][86] Minas Gerais received generally Italians, looking for arable acreage in the 19th century, and Portugueses early in the 18th during the Gold and Diamond Rush.[72] Minas Gerais was also destination for Germans, Czech, Bulgarians, Romanians, Hungarians, Ashkenazi Jews, Spaniards, Serbians, Greeks, Armenians, and Lebanese who settled the country.[79][86][87]

However, the impact of the White immigration was larger in Southern Brazil, because even though it got a lesser migration, since it had a very small population, the immigration's impact was greater to its demography when compared to other Brazilian regions. The main concentrations in Rio Grande do Sul were Venetian Italians where their dialect is still spoken and Germans from the Hunsrück region of Germany (Rhineland-Palatinate) who also kept their Hunsrückisch dialect known as Riograndensisch, followed by Poles. Their arriving numbers supplanted the previous Iberian population, founding cities like Novo Hamburgo and Garibaldi.[75][80][88] German immigrants first arrived in 1824 settling in the Sinos River Valley, where one of the first colonies to take an urbanized figure was Hamburger Berg, future Novo Hamburgo, dismembered from or spun out of São Leopoldo, dubbed the cradle of German culture in Brazil.[89] Its capital, Porto Alegre, has the third largest Jewish population in the nation.[90]

The vast majority of Slavs is concentrated in Paraná, mainly Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians, followed by German and Italian dwellers in the countryside who also arrived to populate the sparsely inhabited South. Some localities like Mallet, a 19th-century settlement founded by Poles from Austrian Galicia (Eastern Europe) and Ukrainians that grew up to be a town, still maintain both their languages and traditions in a Polish-Ukrainian continuum. After 1909 Dutch settlers became accountable for the dairy farming development in the prairies region of the state, known as Campos Gerais do Paraná, where today are the towns of Castro and Carambeí dubbed Little Holland. The Castro region also received many Lithuanians. The capital, Curitiba, is home to a large figure of Volga Germans that outnumbered the initial and primary Bandeirante descent population during the Imperial period, Faroese people and other Scandinavians, as well as to Slavs, Italians, French, Swiss, Spaniards and one of the country's Jewish communities.[72][75][79][80][88][91][92][93]

Santa Catarina where over 50% of the population has German, Austrian and Luxembourgish ancestry (the local Hunsrückisch is known as Katharinensisch,[94] East Pomeranian is still spoken in the town of Pomerode and Southern Austro-Bavarian by the Tyrolean population in Treze Tílias) was also the main destination for Danes and the state that was sparsely populated and had its shore mainly inhabited by Azoreans in the 18th century (e.g. Laguna born Anita Garibaldi, wife and comrade-in-arms of Italian Unification revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi), also received Italians, French, Swedes, Norwegians, Swiss, Lithuanians and Latvians, Estonians, Finns, Poles, Slovenians, Croatians, Belgians and Spaniards to populate its interior during the 19th century. The town of Brusque founded by Austrian Baron von Schneeburg bringing German families from the Grand Duchy of Baden to settle in the northeast of Santa Catarina, besides receiving additional waves of Italians from the Tyrol–South Tyrol–Trentino Euroregion, Poles and Swedes, was also one of the destinations in the South and Southeast for American Confederate settlers in 1867, differing from São Paulo and Paraná colonies, where the American Confederate presence gave birth to new towns such as Americana in São Paulo. Neighboring towns such as Nova Trento founded in 1875, similarly received subjects from the Austro-Hungarian Empire because Italian-speaking Tyroleans known as trentinos and Germans from the Kingdom of Prussia, historic Swabia and Baden faced an immense crisis in the agricultural sector caused by the conflicts of the unification of Italy and Germany respectively, that weakened local trade. Istrian Italians under the Austrian Empire rule also fled Istria to settle in Brazil, and a few towns like Nova Veneza, founded in 1891 still have an over 90% Venetian population of which many still speak the Talian dialect. Most Venetians settled after the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866, when Venice, along with the rest of the Veneto, became part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy.[72][34][75][80][86][88][95][96]

| Town name | State | Main ancestry | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nova Veneza | Santa Catarina | Italian | 95%[97] |

| Pomerode | Santa Catarina | German | 90%[98] |

| Prudentópolis | Paraná | Ukrainian | 70%[99] |

| Treze Tílias | Santa Catarina | Austrian | 60%[100] |

| Dom Feliciano | Rio Grande do Sul | Polish | 90%[101] |

The Europeanization was so longed that by 1895 the government of São Paulo spent about 15% of its annual budget on subsidies for immigrants.[102]

Portuguese

Between 1500 and 1808, it is estimated that 500,000 Portuguese went to live in Brazil;[5] the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics estimated the number of Portuguese settlers at 700,000, from 1500 to 1760.[23]

After independence in 1822, about 1.79 million Portuguese immigrants arrived in Brazil, most of them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[34] Most of these immigrants settled in Rio de Janeiro.[72]

Portuguese immigration to Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries was marked by its concentration in the most urbanized states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The immigrants opted mostly for urban centers. In Portugal, trade was seen as the great chance of enrichment for those who emigrated and this explains why most Portuguese immigrants chose the city of Rio de Janeiro as their main destination. Many of those who arrived came to work as clerks in one of the countless warehouses of the city. Others survived as small street traders, selling from brooms to live birds, or working as dockers in the port area.[103]

Portuguese women appeared with some regularity among immigrants, with percentage variation in different decades and regions of the country. However, even among the influx of Portuguese immigrants at the turn of the 20th century, there were 319 men to each 100 women among them.[104] The Portuguese were different from other immigrants in Brazil, like the Germans,[105] or Italians[106] who brought many women along with them (even though the proportion of men was higher in any immigrant community). Despite the smaller female proportion, Portuguese men married mainly Portuguese women. Female immigrants rarely married Brazilian men. In this context, the Portuguese had a rate of endogamy which was higher than any other European immigrant community, and behind only the Japanese among all immigrants.[107]

Portuguese people are still the biggest group of foreigners living in the country, with 137,973 Portuguese-born people living in Brazil as of 2010.[108] The first half of 2011 alone saw an increase of 52,000 Portuguese nationals applying for a permanent residence visa while another large group was granted Brazilian citizenship.[109][110]

Italians

About 1.64 million Italians arrived in Brazil, starting in 1875.[34] First they settled as small landowners in rural communities across Southern Brazil. In the late 19th century, the Brazilian State offered land to immigrants, in conditions that made it possible to buy them.[111] Later, their destination were mostly the coffee plantations in the Southeast, especially the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, where they initially worked for the local landowners, either for a wage or under a contract that allowed them to use a portion of land for subsistency, in exchange for labour in the plantation.[112]

In São Paulo capital, which came to be labeled an "Italian city" in the early twentieth century, Italians engaged mainly in the incipient industry and urban services activities. They came to represent 90% of the 60,000 workers employed in São Paulo factories in 1901.[113]

Italians made up the main group of immigrants to Brazil in the late 19th century.[34]

The largest group of Italian settlers came from Veneto and, according to Ethnologue, today around 4 million people still speak the Venetian dialect called Talian or Veneto in Southern Brazil.[114] Veneto was followed mainly by Campania, Lombardy, Calabria, Abruzzi e Molise, Tuscany and Emilia Romagna.[70]

Spaniards

About 720,000 Spaniards came to Brazil, starting in the late 19th century.[34] Most of them were attracted to work in the coffee plantations in the State of São Paulo.[72]

São Paulo attracted between 66% and 75% of the Spaniards who migrated to Brazil. In this state, 55% were from Andalusia and 23% from Galicia.[52][59] Most of them had their passage by ship paid by the Brazilian government, emigrated in families and were taken to the coffee farms for the needed manpower.[52]

In the other Brazilian states, Spanish immigrants from Galicia predominated and those were predominantly males, who emigrated alone and paid for their passage by ship.[59] Galician smallholders and artisans settled mainly in urban areas of Brazil and eventually became factory workers.[115]

Germans and Austrians

About 260,000 Germans settled in Brazil, starting in 1824.[34] They were the fourth largest nationality to immigrate to Brazil, after the Portuguese (1.8 million), the Italians (1.6 million), the Spaniards (0.72 million); Germans were followed by the Japanese (248,000), the Poles and the Russians.[34]

Most German immigrants in Brazil became small landowners in the interior of the southern region. They started very poor but, over time, their settlements grew and they prospered. In the 1930s, while occupying less than 0.5% of Brazil's arable land, German communities generated 8% of the Brazilian agricultural production. Over time, some of the German settlements became urbanized and by 1930 Germans owned 10% of industries and 12% of trade in Brazil. Other settlements remained rural and rather isolated and even today many of their inhabitants are still able to speak German or a Germanic dialect.[116][117]

Brazil is home to the second largest population of German descent outside Germany, only behind the United States, and German is the second most spoken language in the country, after Portuguese.[118][119][120] According to Ethnologue, Standard German is spoken by 1.5 million people and Brazilian German encompass assorted dialects, including Riograndenser Hunsrückisch spoken by over 3 million Brazilians.[121][122][123]

Today more speakers of the East Pomeranian dialect can be found in Brazil than its original Low German-speaking land, and the dialect is especially spoken in Pomerode, Santa Catarina as well as in the states of Espírito Santo and Rio Grande do Sul where it enjoys co-official status.[124] Other dialects include Luxembourgish (part of the Moselle Franconian dialects group together with Hunsrik), Swiss Alemannic, Low Saxon–rooted Plautdietsch, spoken by Mennonites from the former Soviet Union (since the 1930s),[125][126] Southern Austro-Bavarian, Tyrol dialect and Vorarlberg High Alemannic German, especially in Dreizehnlinden, Santa Catarina (since 1933),[127] and Danube Swabian in Guarapuava, Paraná (since 1951).[128]

The vast majority of Germans settled in the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Rio de Janeiro. Less than 5% of Germans settled in Minas Gerais, Pernambuco, and Espírito Santo.[34]

The most influenced state by the German immigration was Santa Catarina, where Germans and Austrians were about 50% of all foreigners (Germans, 40%; Austrians, 10%), it was the only state where Germans were the principal nationality among foreigners. Other states with some significant proportion were Rio Grande do Sul (Germans, slightly over 25%) and Paraná (Germans, 10%; Austrians, 10%).[34] The Oktoberfest of Blumenau in Santa Catarina is Brazil's largest and the world's second largest (after Germany's main beer festival in Munich).[129]

Endogamy was the rule among the 19th-century German, Austrian and Luxembourgish colonies and young married women in the homogeneously isolated German colonies settled in the three Southern states had a high fertility rate of 8–9 children per woman; that was especially the case for those youths married between 20 and 24 years old.[86]

In Rio Grande do Sul, the House of Representatives recognized Hunsrückisch as an official Intangible cultural heritage of historical value to be preserved.[130][131]

Poles

Poles came in significant numbers to Brazil after 1870. Most of them settled in the State of Paraná, working as small farmers.[79][91][92] From 1872 to 1919, 110,243 "Russian" citizens entered Brazil. In fact, the vast majority of them were Poles ("Russian" Catholics), since, up to 1917, a part of Poland was under Russian rule due to the Partitions of Poland and ethnic Poles immigrated with Russian passports.[132]

Polish can still be heard in small towns such as Mallet, Paraná, where the vast majority of the population descends from Western and Northern Slavic settlers who arrived in Brazil in the 1890s (mostly Poles who came from Galicia which was under Austrian rule then).[133][134][121][92]

The city of Curitiba has the second largest Polish diaspora in the world (after Chicago) and Polish music, dishes and culture are quite common in the region.[80]

Swiss

In 1818, King John VI of Portugal and Brazil, then resident in Rio de Janeiro, authorized the entry into Brazil of Swiss immigrants from the canton of Fribourg (Switzerland). The parish founded in 1819 was given the name of "São João Batista de Nova Friburgo" (Saint John the Baptist of New Fribourg), German: Neufreiburg.[135]

Luxembourgers

An estimated 80,000 Brazilians are of Luxembourgian descent due to a small immigration of Luxembourgers to Brazil, mostly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[136][137]

Ukrainians

More than 20,000 Ukrainians came to Brazil between 1895 and 1897, settling mostly in the countryside of Paraná and working as farmers in the state, today a land of regnant Orthodox churches, where Slavic traditions can be witnessed all over the territory.[91][93][138]

Dutch (Netherlands) and Flemish

Dutch people first settled in Brazil during the 17th century, with the region of Pernambuco being a colony of the Dutch Republic from 1630 to 1654. The Dutch were then expelled as Portugal regained control of the region.[44][139]

During the 19th and 20th century, a few immigrants from the Netherlands came to the central and southern states of Brazil.[140][141] The first Dutch immigrants to South America after its independence waves from their metropoles went to the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo between 1858 and 1862, where they founded the settlement of Holanda, a colony of 500 mainly Reformed folk from West Zeeuws-Vlaanderen in the Dutch province of Zeeland.[73] Dutch and other Low Franconian languages are still spoken in São Paulo (state), especially Holambra (named after Holland-America-Brazil), famous for its tulips and the annual Expoflora event, Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul and around Ponta Grossa, Castrolanda and Carambeí known as little Holland, in the plains of Paraná, headquarters of several food companies and a dairy farming region.[121][91]

Most Belgian settlements took place in Southern and Southeastern Brazil. Among the Flemish colonies are Itajaí (Santa Catarina – 1845), Porto Feliz (São Paulo – 1888), Taubaté (São Paulo – 1889),[142] and Botucatu (São Paulo – 1960). Many Belgians also preferred to establish their lives in urban centers such as Rio de Janeiro capital.

French and Walloons

Between 1850 and 1965 around 100,000 French people immigrated to Brazil. The country received the second largest number of French immigrants to South America after Argentina (239,000). It is estimated that there are 1.2 million Brazilians of French and Walloon descent today.[143][144]

Scandinavian countries

The relations between Brazil and Sweden are rooted in the family ties of the Brazilian and the Swedish Royal Families and in the Swedish emigration to Brazil in the end of the 19th century. The wife of King Oscar I of Sweden and Norway, Queen Joséphine of Leuchtenberg, was sister to Amélie of Leuchtenberg, wife of Emperor Pedro I of Brazil. Diplomatic relations between Brazil and Sweden were established in 1826. During the mid to late 19th century many Scandinavians arrived in Brazil, particularly to the southern states as well as Rio de Janeiro, which features a Scandinavian Association, and São Paulo, where the Scandinavian church is based.

Russians

.jpg.webp)

Brazil was among the main destinations for Russian refugees during the 20th century.[146] Some Chinese immigrants to Brazil were of Russian descent, belonging to the country's ethnic Russian community.[147]

Balts (Lithuanians and Latvians)

.jpg.webp)

Lithuanian migration peaked in the 1920s and 1930s, when 35% of all emigrants from interwar Lithuania chosen Brazil as their destination, around 50,000 moved in.[148][79][149] Besides Lithuanians, the Baltic diaspora also comprises one of the largest Latvian populations.[79][150][151]

The first Lithuanians to set foot on Brazil in the 19th century had as their destination the newly established colony of Ijuí, situated on the red and fertile soil of the northwestern part of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, while most Lithuanians and Latvians would settle in São Paulo posteriorly. Besides São Paulo, other states that received Baltic people during the 20th century were Paraná, Rio de Janeiro, Santa Catarina and Espírito Santo. Latvian is still spoken in Santa Catarina and Paraná.

Today, the state of São Paulo is home to the majority of the Lithuanian Brazilians, and its capital hosts the only true Lithuanian neighborhood in South America – Vila Zelina. Its construction was carried out ~1927 when Lithuanian immigration was peaking. The district is centered around Republic of Lithuania Plaza (Praça República Lituânia), where 7 streets meet up (one of them named after a Lithuanian priest Pijus Ragažinskas (Pio Ragazinskas, 1907–1988) who started the only Lithuanian-Brazilian newspaper "Mūsų Lietuva"). Liberty statue (1977) that crowns the Plaza center is modelled after the one in Kaunas, Lithuania (that original symbol of interwar Lithuanian freedom had been pulled down by Soviets in 1950, making its reconstruction in communism-free São Paulo even more symbolic). It bears the inscription "Lietuviais esame gimę, lietuviais turime būt" ("Lithuanians we are born, Lithuanians we must be") – lyrics of a traditional patriotic song. They are joined by Columns of Gediminas, a symbol of the famous Gediminid dynasty (1315–1572) which brought the medieval Grand Duchy of Lithuania to its glory as the Europe's largest state. There's also a Lithuanian church facing the square.[149]

Nationalities of Uralic languages (Finns, Hungarians and Estonians)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Mostly Hungarians and Finns, followed by an Estonian minority of Finnic language, who also composes the Baltic Finns group.[76][79]

Most Hungarian descendants live in São Paulo, where there are several Hungarian associations. Hungarians have two institutions with legal personality: the Brazilian-Hungarian Aid Association and the Brazilian-Hungarian Cultural Association and both own the auditorium Hungarian House. The Kálmán Könyves Free University is another organization to form the additional group.[77]

Penedo, a small town located near Itatiaia National Park, was the first Finnish settlement to be established in Brazil. Finnish architecture, cuisine and traditional customs such as saunas, are still present and can be seen.[152][153][154]

British, Scottish and Irish

.jpg.webp)

British immigration to Brazil can be divided into four main periods: colonial, monarchical, Old Republic and the 1960s/1970s. Most of the oldest capitals in Brazil possess colonial Anglican cemeteries or English cemeteries.[155] And a group of Scottish religious dissidents established a settlement in the northeast of Brazil during the colonial period. After Brazil was promoted to kingdom, the 19th century witnessed a new wave of British citizens settling in the country, since England had special trading privileges with the nation.[82] English were responsible for most of the railways, public lighting and urban transportation like trams and Irish worked as manual workers in constructions such as the Madeira-Mamoré Railway in the rainforest.[83][156][157]

The Anglo-Scots-Brazilian Charles William Miller is celebrated for making football popular in Brazil and deemed as the father of Brazilian football. Oscar Cox and his sibling Edwin, both children of an English diplomat, are also praised for pioneering football in Brazil and introducing the sport especially to the city of Rio de Janeiro during the 1900s.[158] Oscar organized the first football match in the history of the state of Rio de Janeiro in 1901 and then proceeded to São Paulo, with his select team, to play against the squad led by Charles Miller, who had started the process of disseminating football in São Paulo back in 1894.[159] Even though the sport had been played in an informal manner since the 1870s by British, Dutch and French sailors, as well as by European immigrants, Miller's merit lays in the fact that he arrived in Brazil with the necessary apparatus for the organized practice of football, being the first team manager, and consolidating it within sports clubs by captivating the public, considering that the then British-Brazilians and other citizens of the period were more accustomed to cricket.[160][161] Bertha Lutz was a Brazilian zoologist, politician and diplomat born in 1894. Lutz, whose mother was a British nurse and father a Swiss Brazilian pioneering physician and epidemiologist, became a leading figure in both the Pan American feminist movement fighting for women's suffrage and human rights movement. The 1960s and 1970s also saw new waves of English, Scottish and Welsh nationals, especially youths, immigrating to Brazil.[162][163]

Americans (United States)

At the end of the American Civil War in the 1860s, a migration of Confederates to Brazil began, with the total number of immigrants estimated in the thousands. They settled primarily in Southern and Southeastern Brazil founding many towns in the state of São Paulo: Americana, Campinas, Santa Bárbara d'Oeste, Juquiá, New Texas, Eldorado (former Xiririca) as well as moving to the capital São Paulo.[164]

The bordering state of Paraná was the main destination in the South, followed by Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, where Americans arrived in 1867 settling in growing towns such as Brusque. The city of Rio de Janeiro, the town of Rio Doce in Minas Gerais and the state of Espírito Santo were other destinations in the Southeast region. Later waves settled in Santarém, Pará—in the north of the Amazon River—as well as in the states of Bahia and Pernambuco, adding a significant number of immigrants to the region's population. Altogether, close to 25,000 American immigrants settled in Brazil during the 19th century. That is one of the main reasons why emperor Dom Pedro II was the first foreign Chief of State and Head of Government to visit Washington, D.C. in 1876 and also attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.[165]

The first Confederado recorded was Colonel William H. Norris, a former senator of Alabama who left the U.S. with 30 Confederate families and arrived in Rio de Janeiro on 27 December 1865.[166] The settlement at Santa Bárbara D'Oeste is sometimes called the Norris Colony. The New Texas settlement leader, Frank McMullen, also left the U.S. in 1865 with former citizens of the Confederacy.[167][168][169] Ethnically the Confederados cultural sub-group, the way how the Confederate colonies were named, were primally Scottish, English-Welsh, Irish, Scandinavian, Dutch and German, (ethnic Germans among Romanian, Czech, Russian and Polish immigrant descendants).[164] More recently, other waves of American nationals became residents in the country.

Pérola Ellis Byington (Pearl) born in 1879 to the American immigrants Mary Elisabeth Ellis and Robert Dickson McIntyre in Santa Bárbara D'Oeste and married to the industrialist Alberto Jackson Byington, was an accoladed educator, social activist, philanthropist and volunteer for the American and Brazilian Red Cross, who had hospitals and a town in Paraná named after her.[170][171][172] Other famous Brazilians who descend from American immigrants are the former Chief Justice of Brazil Ellen Gracie Northfleet, first woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court; Warwick Estevam Kerr, a geneticist, agricultural engineer, entomologist, professor and scientific leader, notable for his discoveries in the genetics and sex determination of bees and the singer Rita Lee Jones, dubbed "the mother of Brazilian rock'n'roll".

Levantine Arabs

.jpg.webp)

Brazil has the largest Lebanese and Syrian population outside the Levant region, Christians in the great majority.[173][174] Lebanese and Syrians make up some of the largest Asian communities in the country.[175] There were many causes for Arabs to leave their homelands in the Ottoman Empire; overpopulation in Lebanon, conscription in Lebanon and Syria, and religious persecution by the Ottoman Turks.

Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews

Brazil is also home to one of the top 10 largest Jewish diasporas on Earth, most of them of Ashkenazi background but also Sephardi Jews included. Brazil figures on the diasporas list together with Argentina, and São Paulo has one of the largest Jewish populations by urban area on the planet. Ashkenazi Jews first arrived during Imperial times, when the liberal second emperor of Brazil welcomed a few thousands of families facing persecution in Europe during the 1870s and 1880s.[42] Two heavier influxes took place during the 20th century. The earliest right after the Great War and the second inrush between the 1930s and 1950s.[80][42] Anusim or Portuguese and Dutch Marrano Crypto Jews can be found in every one of the 5 geographical regions, but are most common in the Northeast, with Pernambuco having one of the largest Converso populations due to colonial history. Brazil has the oldest synagogue in the Americas founded during Dutch Brazil rule, Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue, located in Recife.[43] Erected in 1636, its foundations have been recently rediscovered, and the 20th-century buildings on the site have been altered to resemble a 17th-century Dutch synagogue. There is now a museum on the site praising it as one of the oldest synagogues in the world. After the Dutch defeat, part of those Jews moved to North America, settling in New Amsterdam, Dutch colony that would become today's New York.[43][44] They founded in New Amsterdam the oldest Jewish congregation in the US, the Congregation Shearith Israel.

The capital of São Paulo together with the satellite city of Campinas in the metropolitan area has the greatest number of Jews in the country,[74] followed by Rio de Janeiro capital[84] and Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul.[90] Other state capitals in the nation that figure among the largest Jewish communities are Curitiba in Paraná,[176][177] Belo Horizonte in Minas Gerais,[178][177] Recife,[43] the national capital Brasília in the Federal District,[179] Belém,[178][177] Manaus[177] and Florianópolis.[180][181][182][183]

In August 2004, the mayor of São Paulo, a metropolis home to 77,000 Jews, declared her city a sister city with Tel Aviv. Mayor Marta Smith Suplicy said the new status would strengthen ties between both Brazilians and Israelis. Suplicy, who had recently married a Jew, added that the new status would be a kickoff for urban, cultural, scientific, tourist and economic programs.[42]

The Anti-Defamation League and other Israeli/Jewish papers and surveys placed Brazil among the least anti-Semitic nations in the Americas and Western Europe, which subsequently means among the least anti-semitic ones on the planet.[184][185] And Jewish Brazilian personalities stated in a jocose form that the only threat they face is assimilation by marriage with Europeans, Levantine Arabs and East Asians. Intermarriage between Jews and non-Jewish descendants might have an even higher rate than in the US.[42]

Greeks

Greek immigration to Brazil can be divided into three periods. The first Greek families arrived during the monarchical period in the 19th century, followed by two larger influxes: the period right after the break of the Great War in 1914 and prolonged until the 1930s, and the final one right after WW2, with most Greeks settling in São Paulo.[186][187][188]

Notable people

Whites constitute the majority of Brazil's population regarding the total numbers within a single racial group.[178][189][190]

Whites dominate Brazilian arts, business and science. Overall, whites constitute 86.3% of the 1% richest population of Brazil as of 2007.[191] The majority of representatives of the 20 largest companies in Brazil are white. These companies include Petrobrás, Oi telecommunications, Ambev and Gerdau and Braskem groups, and according to the Valor 1000 ranking from 2014, 95% of these representatives declare themselves as white, 5% declare themselves as brown and none declared as blacks or yellow (ethnic East Asian).[192]

The most successful Brazilian entrepreneurs have historically been white. Jorge Paulo Lemann, an investor and the child of Swiss immigrants, is ranked as the 19th richest person in the world by Forbes, with an estimated net worth of US$38.7 billion. Eduardo Saverin is the Co-founder of Facebook, one of the world's wealthiest companies, and most powerful social media platforms, was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Whites dominate Brazilian fashion. Gisele Bündchen has been the highest paid model in the world for 10 years. With a reported net worth of $290 million, she is widely recognized as the poster child for Brazilian fashion models, being the first 'breakthrough' model from Brazil. Alessandra Ambrosio is most famous for being a Victoria's Secret and 'PINK' model. Earning an estimated $6.6 million per annum. Alexandre Herchcovitch is a well-known fashion designer in the Paris, London, New York and Tokyo circuits.

Xuxa Meneghel, a television presenter, film actress, singer and successful businesswoman born in Rio Grande do Sul, has the highest net worth of any Brazilian female entertainer, estimated at US$350 million.[193][194][195][196][197]

Whites also dominate the sciences and academics. According to a Folha University Ranking, among the rectors and vice-chancellors of the 25 top universities, 89.8% are white; 8.2% are brown; 2% are black; none are yellow (East Asian).

In the world of Brazilian sports, some of the most successful Brazilian athletes have been white. Ayrton Senna was among the most dominant and successful Formula One drivers of the modern era and is considered by many as the greatest racing driver of all time.[198][199] Robert Scheidt is one of the most successful sailors at Olympic Games[200] and one of the most successful Brazilian Olympic athletes.[201] Zico, the world's best football player of the late 1970s and early 80s.[202]

Others include, Gustavo Kuerten, the only Brazilians tennis player to be ranked nr 1,[203][204] César Cielo the most successful Brazilian swimmer in history, having obtained three Olympic medals. Oscar Schmidt, who was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2013.[205] The Brazil men's national volleyball team is the most successful volleyball team in the world and is mostly white (Gustavo Endres, Giba, André Heller, Murilo Endres), and many others.

Among women Maria Esther Bueno is the most successful Brazilian tennis player at the Grand Slam tournaments. She won seven single titles (four wins at the US Open and three at Wimbledon) and twelve doubles titles (five at Wimbledon, four at the US Open, two in the Roland Garros, including a mixed doubles, and once at the Australian Open).[206][207]

Demography

By state

The Brazilian states with the highest percentages of whites are the three located in the South of the country: Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná. These states, along with São Paulo, received an important influx of European immigrants in the period of the Great Immigration (1876–1914).

- Santa Catarina: 83.85% white

- Rio Grande do Sul: 83.21%

- Paraná: 70.05%

- São Paulo: 63.65%

- Rio de Janeiro: 54.50%

- Mato Grosso do Sul: 51.78%

- Espírito Santo: 50.45%

- Minas Gerais: 45.06%

- Federal District 41.82%

- Goiás: 41.43%.[208]

The Brazilian states with the lowest percentages of whites are located in the North, where there is a strong Amerindian influence in the population's racial composition, and in part of the Northeast, notably in Bahia and Maranhão, where African influence is stronger.[209]

States with high absolute numbers:

- São Paulo: 30,976,877 whites

- Minas Gerais: 9,019,164

- Rio Grande do Sul: 8,973,928

- Rio de Janeiro: 8,513,778

- Paraná: 7,620,982

- Santa Catarina: 5,297,900

- Pernambuco: 3,151,550

- Ceará: 2,883,000

- Bahia: 2,864,000

- Goiás: 2,618,000

- Espírito Santo: 1,835,000

- Mato Grosso: 1,179,000

- Mato Grosso do Sul: 1,157,000

- Federal District: 1,084,418[211][212]

| Federative Units | White Population 1940(%)[213] | White Population 2009(%)[214] |

|---|---|---|

| Santa Catarina | 94,4% | 83,8% |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 88,7% | 82,3% |

| Paraná | 86,6% | 70,0% |

| São Paulo | 84,9% | 63,1% |

| Goiás | 72,1% | 43,6% |

| Rio de Janeiro (city) | 71,1%* (in the then Federal District*) | 55,0%* (in Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro*) |

| Espírito Santo | 67,5% | 44,2% |

| Minas Gerais | 64,2% | 47,2% |

| Rio de Janeiro (state) | 63,8% | 54,5% |

| Alagoas | 56,7% | 26,8% |

| Pernambuco | 54,4% | 36,6% |

| Acre | 54,3% | 26,9% |

| Paraíba | 53,8% | 36,4% |

| Ceará | 52,6% | 31,0% |

| Mato Grosso | 50,8% | 38,9% |

| Maranhão | 46,8% | 23,9% |

| Sergipe | 46,7% | 28,8% |

| Piauí | 45,2% | 24,1% |

| Pará | 44,6% | 21,9% |

| Rio Grande do Norte | 43,5% | 36,3% |

| Amazonas | 31,2% | 20,9% |

| Bahia | 28,7% | 23,0% |

- Excludes states created after 1940.

Cities and towns

In a list of the 144 Brazilian towns with the highest percentages of whites, all the cities were located in two states: Rio Grande do Sul or Santa Catarina. All these towns are settled predominantly by Brazilians of German or Italian descent and are usually very small.[215]

In the 19th century, many German and Italian immigrants were attracted by the Brazilian government to populate inhospitable areas in the South of the country. Slavery was banned in these settlements and many of these areas remained settled exclusively by European immigrants and their descendants.[215]

Until quite recently, many of these towns have been relatively isolated areas, and German or Italian cultural traditions are still very strong, with many of their inhabitants being able to speak German or Italian, especially in the more rural areas.[117]

The Brazilian towns with the largest percentages of whites are the following:[216]

- Montauri (Rio Grande do Sul): 100% White (1,615 inhabitants)

- Leoberto Leal (Santa Catarina): 99.82% (3,348 inhabitants)

- Pedras Grandes (Santa Catarina): 99.81% (4,849 inhabitants)

- Capitão (Rio Grande do Sul): 99.77% (2,751 inhabitants)

- Santa Tereza (Rio Grande do Sul): 99.69% (1,604 inhabitants)

- Cunhataí (Santa Catarina): 99.67% (1,740 inhabitants)

- São Martinho (Santa Catarina): 99.64% (3,221 inhabitants)

- Guabiju (Rio Grande do Sul): 99.62% (1,775 inhabitants)

The Brazilian towns with the lowest percentages of whites are located in Northern and Northeastern Brazil and are also small.

- Nossa Senhora das Dores (Sergipe): 0.71% White (23,817 inhabitants, 98.16% "Multiracial")

- Santo Inácio do Piauí (Piauí): 2.25% (3,523 inhabitants, 96.90% "Multiracial")

- Uiramutã (Roraima): 2.33% (6,430 inhabitants, 74.41% Amerindian)

- Ipixuna (Amazonas): 2.35% (17,258 inhabitants, 80.46% "Multiracial")

- Caapiranga (Amazonas): 2.97% (9,996 inhabitants, 81.68% "Multiracial")

- Fonte Boa (Amazonas): 3.01% (37,595 inhabitants, 86.46% "Multiracial")

- Santa Isabel do Rio Negro (Amazonas): 3.15% (16,622 inhabitants, 59.62% "brown", 34.75% Amerindian)

- Serrano do Maranhão (Maranhão): 3.30% (5,547 inhabitants, 69.08% "Multiracial", 24.97% Black)

Genetic research

The genes can reveal from what part of the world the oldest ancestors of the paternal and maternal line of a person came from. The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is present in all human beings and passed down through the maternal line, i.e. the mother of a mother of a mother etc. The Y chromosome is present only in males and passed down through the paternal line, i.e., the father of a father of a father etc. The mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome suffer only minor mutations through centuries, thus can be used to establish the paternal line in males (because only males have the Y chromosome) and the maternal line in both males and females.

According to a genetic study about Brazilians (based upon about 200 samples), on the paternal side, 98% of the white Brazilian Y Chromosome comes from a European male ancestor, only 2% from an African ancestor and there is a complete absence of Amerindian contributions. On the maternal side, 39% have European Mitochondrial DNA, 33% Amerindian and 28% African female ancestry. This, considering the facts that the slave trade was effectively suppressed in 1850, and that the Amerindian population had been reduced to small numbers even earlier, shows that at least 61% of white Brazilians had at least one ancestor living in Brazil before the beginning of the Great Immigration. This analysis, however, only shows a small fraction of a person's ancestry (the Y Chromosome comes from a single male ancestor and the mtDNA from a single female ancestor, while the contributions of the many other ancestors is not specified).[218]

According to another genetic research (based upon about 200 samples again) over 75% of caucasians from North, Northeast and Southeast Brazil would have over 10% Sub-Saharan African genes, and that this would also be the case with Southern Brazil for 49% of the caucasian population. According to this study, in all United States 11% of Caucasians have over 10% African genes. Thus, 86% of Brazilians would have at least 10% of genes that came from Africa. The researchers however were cautious about its conclusions: "Obviously these estimates were made by extrapolation of experimental results with relatively small samples and, therefore, their confidence limits are very ample". A new autosomal study from 2011, also led by Sérgio Pena, but with nearly 1000 samples this time, from all over the country, shows that in most Brazilian regions most Brazilians "whites" are less than 10% African in ancestry, and it also shows that the "pardos" are predominantly European in ancestry, the European ancestry being therefore the main component in the Brazilian population, in spite of a very high degree of African ancestry and significant Native American contribution.[38] Other autosomal studies (see some of them below) show a European predominance in the Brazilian population.

Another genetic research suggested that the white Brazilian population is not genetically homogenous, as its genomic ancestry varies in different regions. Samples of white males from Rio Grande do Sul have showed significant differences between whites of different localities of state. In a sample from the town of Veranópolis, heavily settled by people of Italian descent, the results from the maternal and paternal sides showed almost complete European ancestry. On the other hand, a sample of whites from several other regions of Rio Grande do Sul showed significant fractions of Native American (36%) and African (16%) mtDNA haplogroups.[219]

Another study (based on blood polymorphisms, from 1981) carried out in one thousand individuals from Porto Alegre city, Southern Brazil, and 760 from Natal city, Northeastern Brazil, found whites of Porto Alegre had 8% of African alleles and in Natal the ancestry of the samples total was characterized as 58% white, 25% black, and 17% Amerindian. This study found that persons identified as white or Pardo in Natal have similar ancestries, a dominant European ancestry, while persons identified as white in Porto Alegre have an overwhelming majority of European ancestry.[220]

According to an autosomal DNA genetic study from 2011, both "whites" and "pardos" from Fortaleza have a predominantly degree of European ancestry (>70%), with minor but important African and Native American contributions. "Whites" and "pardos" from Belém and Ilhéus also were found to be pred. European in ancestry, with minor Native American and African contributions.[38]

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Porto Alegre Sérgio Pena et al. 2011.[38] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| colour | Amerindian | African | European | |

| white | 9.3% | 5.3% | 85.5% | |

| pardo | 11.4% | 44.4% | 44.2% | |

| black | 11% | 45.9% | 43.1% | |

| total | 9.6% | 12.7% | 77.7% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Fortaleza Sérgio Pena et al. 2011.[38] | ||||

| colour | Amerindian | African | European | |

| white | 10.9% | 13.3% | 75.8% | |

| pardo | 12.8% | 14.4% | 72.8% | |

| black | N.S. | N.S. | N.S | |

| Genomic ancestry of non-related individuals in Rio de Janeiro Sérgio Pena et al. 2009[221] | ||||

| Cor | Number of individuals | Amerindian | African | European |

| White | 107 | 6.7% | 6.9% | 86.4% |

| "parda" | 119 | 8.3% | 23.6% | 68.1% |

| "preta" | 109 | 7.3% | 50.9% | 41.8% |

According to another study, autosomal DNA study (see table), those who identified as whites in Rio de Janeiro turned out to have 86.4% – and self identified pardos 68.1% – European ancestry on average. Blacks were found out to have on average 41.8% European ancestry.[221]

According to another study (from 1965, and based on blood groups and electrophoretic markers) carried out on whites of Northeastern Brazilian origin living in São Paulo the ancestries would be 70% European, 18% African and 12% Amerindian admixture.[222]