Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire

The Classical Age of the Ottoman Empire (Turkish: Klasik Çağ) concerns the history of the Ottoman Empire from the Conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until the second half of the sixteenth century, roughly the end of the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566). During this period a system of patrimonial rule based on the absolute authority of the sultan reached its apex, and the empire developed the institutional foundations which it would maintain, in modified form, for several centuries.[1] The territory of the Ottoman Empire greatly expanded, and led to what some historians have called the Pax Ottomana. The process of centralization undergone by the empire prior to 1453 was brought to completion in the reign of Mehmed II.

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

Territory

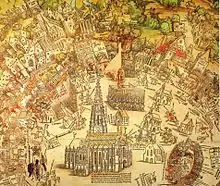

The Ottoman Empire of the Classical Age experienced dramatic territorial growth. The period opened with the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481) in 1453. Mehmed II went on to consolidate the empire's position in the Balkans and Anatolia, conquering Serbia in 1454–5, the Peloponnese in 1458–9, Trebizond in 1461, and Bosnia in 1463. Many Venetian territories in Greece were conquered during the 1463–79 Ottoman-Venetian War. By 1474 the Ottomans had conquered their Anatolian rival, the Karamanids, and in 1475 conquered Kaffa on the Crimean Peninsula, establishing the Crimean Khanate as a vassal state. In 1480 an invasion of Otranto in Italy was launched, but the death of Mehmed II the following year led to an Ottoman withdrawal.[2]

The reign of Bayezid II (r. 1481–1512) was one of consolidation after the rapid conquests of the previous era, and the empire's territory was expanded only marginally. In 1484 Bayezid led a campaign against Moldavia, subjecting it to vassal status and annexing the strategic ports of Kilia and Akkerman. Major Venetian ports were conquered in Greece and Albania during the 1499–1503 war, most significantly Modon, Koron, and Durazzo. However, by the end of his reign, Ottoman territory in the east was coming under threat from the newly established Safavid Empire.[3]

Rapid expansion resumed under Selim I (r. 1512–1520), who defeated the Safavids in the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, annexing much of eastern Anatolia and briefly occupying Tabriz. In 1516 he led a campaign against the Mamluk Sultanate, conquering first Syria and then Egypt the following year. This marked a dramatic shift in the orientation of the Ottoman Empire, as it now came to rule over the Muslim heartlands of the Middle East, as well as establishing its protection over the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. This increased the influence of Islamic practices on the government of the empire, and facilitated much greater interaction between the Arabic-speaking world and the Ottoman heartlands in Anatolia and the Balkans. Under Selim's reign the empire's territory expanded from roughly 341,100 sq mi (883,000 km2) to 576,900 sq mi (1,494,000 km2).[4]

Expansion continued during the first half of the reign of Suleiman I (r. 1520–1566), who conquered first Belgrade (1521) and Rhodes, before invading Hungary in 1526, defeating and killing King Louis II in the Battle of Mohács and briefly occupying Buda. Lacking a king, Hungary descended into civil war over the succession, and the Ottomans gave support to John Zápolya as a vassal prince. When their rivals the Habsburgs began to achieve the upper hand, Suleiman directly intervened by again conquering Buda and annexing it to the empire in 1541. Elsewhere, Suleiman led major campaigns against Safavid Iran, conquering Baghdad in 1534 and annexing Iraq. Ottoman rule was further extended with the incorporation of much of North Africa, the conquest of coastal Yemen in 1538, and the subsequent annexation of the interior.

After the annexation of Buda in 1541 the pace of Ottoman expansion slowed as the empire attempted to consolidate its vast gains, and became engrossed in imperial warfare on three fronts: in Hungary, in Iran, and in the Mediterranean. Additional conquests were marginal, and served to shore up the Ottoman position. Ottoman control over Hungary was expanded in a series of campaigns, and a second Hungarian province was established with the conquests of Temeşvar in 1552. Control over North Africa was increased with the conquest of Tripoli in 1551, while the Ottomans shored up their position in the Red Sea with the annexation of Massawa (1557) and the extension of Ottoman rule over much of coastal Eritrea and Djibouti. By the end of Suleiman's reign the empire's territory had expanded to approximately 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi).[5]

Political history

1451–1481: Mehmed II

The conquest of Constantinople allowed Mehmed II to turn his attention to Anatolia. Mehmed II tried to create a single political entity in Anatolia by capturing Turkish states called Beyliks and the Greek Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia and allied himself with the Crimean Khanate. Uniting the Anatolian Beyliks was first accomplished by Sultan Bayezid I, more than fifty years earlier than Mehmed II, but after the destructive Battle of Ankara back in 1402, the newly formed Anatolian unification was gone. Mehmed II recovered the Ottoman power on other Turkish states. These conquests allowed him to push further into Europe.

Another important political entity which shaped the Eastern policy of Mehmed II was the White Sheep Turcomans. With the leadership of Uzun Hasan, this Turcoman kingdom gained power in the East but because of their strong relations with the Christian powers like Empire of Trebizond and the Republic of Venice and the alliance between Turcomans and Karamanid tribe, Mehmed saw them as a threat to his own power. He led a successful campaign against Uzun Hasan in 1473 which resulted with the decisive victory of the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Otlukbeli.

After the Fall of Constantinople, Mehmed would also go on to conquer the Despotate of Morea in the Peloponnese in 1460, and the Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia in 1461. The last two vestiges of Byzantine rule were thus absorbed by the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of Constantinople bestowed immense glory and prestige on the country.

Mehmed II advanced toward Eastern Europe as far as Belgrade, and attempted to conquer the city from John Hunyadi at the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. Hungarian commanders successfully defended the city and Ottomans retreated with heavy losses, but at the end, Ottomans occupied nearly all of Serbia.

In 1463, after a dispute over the tribute paid annually by the Bosnian kingdom, Mehmed invaded Bosnia and conquered it very quickly, executing the last Bosnian king Stephen Tomašević and his uncle Radivoj.

In 1462 Mehmed II came into conflict with Prince Vlad III Dracula of Wallachia, who had spent part of his childhood alongside Mehmed.[6] Vlad had ambushed, massacred or captured several Ottoman forces, then announced his impalement of over 23,000 captive Turks. Mehmed II abandoned his siege of Corinth to launch a punitive attack against Vlad in Wallachia[7] but suffered many casualties in a surprise night attack led by Vlad, who was apparently bent on personally killing the Sultan.[8] Confronted by Vlad's scorched earth policies and demoralizing brutality, Mehmed II withdrew, leaving his ally Radu cel Frumos, Vlad's brother, with a small force in order to win over local boyars who had been persecuted by Vlad III. Radu eventually managed to take control of Wallachia, which he administered as Bey, on behalf of Mehmet II. Vlad eventually escaped to Hungary, where he was imprisoned on a false accusation of treason against his overlord.

In 1475, the Ottomans suffered a great defeat at the hands of Stephen the Great of Moldavia at the Battle of Vaslui. In 1476, Mehmed won a pyrrhic victory against Stephen at the Battle of Valea Albă. He besieged the capital of Suceava, but could not take it, nor could he take the Castle of Târgu Neamț. With a plague running in his camp and food and water being very scarce, Mehmed was forced to retreat.

Skanderbeg, a member of the Albanian nobility and a former member of the Ottoman ruling elite, led Skanderbeg's rebellion against the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe. Skanderbeg, son of Gjon Kastrioti (who had joined the unsuccessful Albanian revolt of 1432–1436), united the Albanian Principalities in a military and diplomatic alliance, the League of Lezhë, in 1444. Mehmed II was never successful in his efforts to subjugate Albania while Skanderbeg was alive, even though he twice (1466 and 1467) led the Ottoman armies himself against Krujë. During this period Albanians achieved many victories against the Ottomans like the Battle of Torvioll, Battle of Otonetë, Battle of Oranik, Siege of Krujë 1450, Battle of Polog, Battle of Ohrid, Battle of Mokra 1445, and many others, culminating at the Battle of Albulena where the Albanian army destroyed the Ottoman army, inflicting nearly 30,000 casualties on the Ottomans. After Skanderbeg died in 1468, the Albanians couldn't find a leader to replace him, and Mehmed II eventually conquered Krujë and Albania in 1478. The final act of Mehmed II's Albanian campaigns was the troublesome Siege of Shkodra in 1478–79, a siege he led personally against the combined Venetian and Albanian force.

Mehmed II invaded Italy in 1480. The intent of his invasion was to capture Rome and "reunite the Roman Empire", and, at first, looked like he might be able to do it with the quick (15-days to completion) Ottoman invasion of Otranto in 1480, but Otranto was retaken by Papal forces in 1481 after the death of Mehmed. After his death, he was succeeded by his son, Bayezid II.

1481–1512: Bayezid II

When Bayezid II was enthroned upon his father's death in 1481, he first had to fight his younger brother Cem Sultan, who took Inegöl and Bursa and proclaimed himself Sultan of Anatolia. After a battle at Yenişehir, Cem was defeated and fled to Cairo. The very next year he returned, supported by the Mameluks, and took eastern Anatolia, Ankara and Konya, but eventually he was beaten and forced to flee to Rhodes.

Sultan Bayezid attacked Venice in 1499. Peace was signed in 1503, and the Ottomans gained the last Venetian strongholds on the Peloponnesos and some towns along the Adriatic coast. In the 16th century, Mameluks and Persians under Shah Ismail I allied against the Ottomans. The war ended in 1511 in favor of the Turks.

Later that year, Bayezid's son Ahmet forced his father into making him regent. His brother Selim was forced to flee to Crimea. When Ahmet was about to be crowned, the Janissaries intervened, killed the prince and forced Bayezid into calling Selim back and making him the sultan. Bayezid abdicated, and he died immediately after leaving the throne.

1512–1520: Selim I

During his reign, Selim I (so called Yavuz: "the Grim") was able to expand the empire's borders greatly to the south and east.[9] Around 1512 the Ottoman naval fleet developed under his rule,[9] such that the Ottoman Turks were able to challenge the Republic of Venice, a naval power which established its thalassocracy alongside the other Italian maritime republics upon the Mediterranean Region.[10] At the Battle of Chaldiran in eastern Anatolia in 1514, Ottoman forces under Selim I won a decisive victory against the Safavids, ensuring Ottoman security on their eastern front and leading to the conquest of eastern Anatolia and northern Iraq. He defeated the Mamluk Sultanate and conquered most of Syria and Egypt, including Jerusalem as well as Cairo, the residence of the Abbasid caliph.[11]

1520–1566: Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman the Magnificent first put down a revolt led by the Ottoman-appointed governor in Damascus. By August, 1521, Suleiman had captured the city of Belgrade, which was then under Hungarian control. In 1522, Suleiman captured Rhodes. On August 29, 1526, Suleiman defeated Louis II of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács. In 1541 Suleiman annexed most of present-day Hungary, known as the Great Alföld, and installed Zápolya's family as rulers of the independent principality of Transylvania, a vassal state of the Empire. While claiming the entire kingdom, Ferdinand I of Austria ruled over the so-called "Royal Hungary" (present-day Slovakia, North-Western Hungary and western Croatia), a territory which temporarily fixed the border between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans.

The Shi'ite Safavid Empire ruled Persia and modern-day Iraq. Suleiman waged three campaigns against the Safavids. In the first, the historically important city of Baghdad fell to Suleiman's forces in 1534. The second campaign, 1548–1549, resulted in temporary Ottoman gains in Tabriz and Azerbaijan, a lasting presence in Van Province, and some forts in Georgia. The third campaign (1554–55) was a response to costly Safavid raids into the provinces of Van and Erzurum in eastern Anatolia in 1550–52. Ottoman forces captured Yerevan, Karabakh and Nakhjuwan and destroyed palaces, villas and gardens. Although Sulieman threatened Ardabil, the military situation was essentially a stalemate by the end of the 1554 campaign season.[12] Tahmasp sent an ambassador to Suleiman's winter quarters in Erzurum in September 1554 to sue for peace.[13] Influenced at least in part by the Ottoman Empire's military position with respect to Hungary, Sulieman agreed to temporary terms.[14] The formal Peace of Amasya signed the following June was the first formal diplomatic recognition of the Safavid Empire by the Ottomans.[15] Under the Peace, the Ottomans agreed to restore Yerevan, Karabakh and Nakhjuwan to the Safavids and in turn would retain Iraq and eastern Anatolia. Suleiman agreed to permit Safavid Shi’a pilgrims to make pilgrimages to Mecca and Medina as well as tombs of imams in Iraq and Arabia on condition that the shah abolished the taburru, the cursing of the first three Rashidun caliphs.[16] The Peace ended hostilities between the two empires for 20 years.

Huge territories of North Africa up to west of Algeria were annexed. The Barbary States of Tripolitania, Tunisia and Algeria became provinces of the Empire. The piracy carried on thereafter by the Barbary pirates of North Africa remained part of the wars against Spain, and the Ottoman expansion was associated with naval dominance for a short period in the Mediterranean.

Ottoman navies also controlled the Red Sea, and held the Persian Gulf until 1554, when their ships were defeated by the navy of the Portuguese Empire in the Battle of the Gulf of Oman. The Portuguese would continue to contest Suleiman's forces for control of Aden. In 1533 Khair ad Din known to Europeans as Barbarossa, was made Admiral-in-Chief of the Ottoman navies who were actively fighting the Spanish navy.

In 1535 the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (Charles I of Spain) won an important victory against the Ottomans at Tunis, but in 1536 King Francis I of France allied himself with Suleiman against Charles. In 1538, the fleet of Charles V was defeated at the Battle of Preveza by Khair ad Din, securing the eastern Mediterranean for the Turks for 33 years. Francis I asked for help from Suleiman, then sent a fleet headed by Khair ad Din who was victorious over the Spaniards, and managed to retake Naples from them. Suleiman bestowed on him the title of beylerbey. One result of the alliance was the fierce sea duel between Dragut and Andrea Doria, which left the northern Mediterranean and the southern Mediterranean in Ottoman's hands.

Gallery

Mehmed II

Mehmed II Bayezid II

Bayezid II Selim I

Selim I Suleiman I

Suleiman I

See also

References

- Şahin, Kaya (2013). Empire and Power in the reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-107-03442-6.

- Heywood, Colin (2009). "Mehmed II". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. pp. 364–8.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2009). "Bayezid II". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. pp. 82–4.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2009). "Selim I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. pp. 511–3.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2009). "Süleyman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. pp. 541–7.

- "The young Dracula environment and education". Archived from the original on 2009-06-24. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- Mehmed the Conqueror and his time pp. 204–5

- Dracula: Prince of many faces: His life and his times p. 147

- Ágoston, Gábor (2021). "Part I: Emergence – Conquests: European Reactions and Ottoman Naval Preparations". The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 123–138, 138–144. doi:10.1515/9780691205380-003. ISBN 9780691205380. JSTOR j.ctv1b3qqdc.8. LCCN 2020046920.

- Lane, Frederic C. (1973). "Contests for Power: The Fifteenth Century". Venice, A Maritime Republic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 224–240. ISBN 9780801814600. OCLC 617914.

- Alan Mikhail, God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World (2020) excerpt

- Max Scherberger, “The Confrontation between Sunni and Shi’i Empires: Ottoman-Safavid Relations between the Fourteenth and the Seventeenth Centuries” in The Sunna and Shi'a in History: Division and Ecumenism in the Muslim Middle East ed. by Ofra Bengio & Meir Litvak (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) (“Scherberger”), pp. 59-60.

- Mikheil Svanidze, “The Amasya Peace Treaty between the Ottoman Empire and Iran (June 1, 1555) and Georgia,” Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 191-97 (2009) (“Svanidze”), p. 192.

- Svandze, pp. 193-94.

- Douglas E. Streusand, ‘’Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, c. 2011), p. 50.

- Scherberger, p. 60.

Further reading

Surveys

- Howard, Douglas A. (2017). A History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-72730-3.

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1923. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- Hathaway, Jane (2008). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516-1800. Pearson Education Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-582-41899-8.

- Imber, Colin (2009). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power (Second ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-1370-1406-1.

- İnalcık, Halil; Donald Quataert, eds. (1994). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1914. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57456-0.

- Mikhail, Alan. God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World (2020) excerpt on Selim I

Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566)

- İnalcık; Cemal Kafadar, Halil, eds. (1993). Süleyman the Second [i.e. the First] and His Time. Istanbul: The Isis Press. ISBN 975-428-052-5.

- Şahin, Kaya (2013). Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03442-6.