Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan

Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan (ⓘ, Tuñcattŭ Rāmānujan Eḻuttacchan) (Malayalam: തുഞ്ചത്ത് രാമാനുജൻ എഴുത്തച്ഛൻ) (fl. 16th century) was a Malayalam devotional poet, translator and linguist.[1] He was one of the prāchīna kavitrayam (old triad) of Malayalam literature, the other two being Kunchan Nambiar and Cherusseri. He has been called the "Father of Modern Malayalam", the "Father of Modern Malayalam Literature", and the "Primal Poet in Malayalam".[2] He was one of the pioneers of a major shift in Kerala's literary culture (the domesticated religious textuality associated with the Bhakti movement).[3] His work is published and read far more than that of any of his contemporaries or predecessors in Kerala.[4]

Thunchathu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan | |

|---|---|

A modern (2013) representation of Ezhuthachan by artist R. G. V. | |

| Born | 1495 |

| Occupations |

|

| Era |

|

| Known for | Adhyatmaramayanam |

| Movement |

|

He was born in a house called Thunchaththu in present-day Tirur in the Malappuram district of northern Kerala, in a traditional Hindu family.[5][2] Little is known with certainty about his life.[1] His success even in his own lifetime seems to have been great.[5] Later he and his followers shifted to a village near Palakkad, further east into the Kerala, and established a hermitage (the "Ramananda ashrama") and a Brahmin village there.[4] This institution probably housed both Brahmin and Sudra literary students.[1] The school eventually pioneered the "Ezhuthachan movement", associated with the concept of popular Bhakti, in Kerala.[3] Ezhuthachan's ideas have been variously linked by scholars either with philosopher Ramananda, who found the Ramanandi sect, or Ramanuja, the single most influential thinker of devotional Hinduism.[6]

For centuries before Ezhuthachan, Kerala people had been producing literary texts in Malayalam and in the Grantha script.[2] However, he is celebrated as the "Primal Poet" or the "Father of Malayalam Proper" for his Malayalam recomposition of the Sanskrit epic Ramayana.[2][1] This work rapidly circulated around Kerala middle-caste homes as a popular devotional text.[3] It can be said that Ezhuthachan brought the then unknown Sanskrit-Puranic literature to the level of common understanding (domesticated religious textuality).[5] His other major contribution has been in mainstreaming the current Malayalam alphabet.[5][2]

Sources

The first Western scholar to take an interest in Ezhuthachan was Arthur C. Burnell (1871).[7]

The following two texts are the standard sources on Ezhuthachan.

- "Eluttaccan and His Age" (1940) by C. Achyuta Menon (Madras: University of Madras).[1]

- "Adhyatma Ramayanam" (1969) edited by A. D. Harisharma (Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative).

Historical Ezhuthachan

There is no completely firm historical evidence for Ezhuthachan the author.[8]

Main historical sources of Ezhuthachan and his life are

- Quasi-historical verses referring to Ezhuthachan (from Chittur Madhom).[8]

- An institutional line of masters or gurus, beginning with one Thunchaththu Sri Guru, is mentioned in one oral verse from Chittur Madhom.[8] This lineage can be historically verified.[8]

- An inscription giving the details of the founding of the residence (agraharam), hermitage (mathom), and temples in Chittur. This was under the direction of Suryanarayanan Ezhuthachan (with support of the local chieftain).[8] This locale can be historically verified.[8]

Period

Ezhuthachan is generally believed to have lived around the sixteenth or seventeenth century.[9][2]

- Arthur C. Burnell (1871) dates Ezhuthachan to seventeenth century.[9] He discovered the date from a title deed (found in a manuscript collection preserved in Chittur).[10] The deed relates to the date of the founding of the Gurumadhom of Chittur.[10]

- William Logan (1887) dates Ezuthachan to the seventeenth century (he supports the dates given by Burnell).[11]

- Hermann Gundert dates Ezuthachan to the seventeenth century.[12]

- Kovunni Nedungadi dates Ezuthachan to the fifteenth century.[12]

- Govinda Pillai dates Ezuthachan to the fifteenth or sixteenth century.[12] He cites the Kali chronogram 'ayurarogyaa saukhyam' that appears at end of the Narayaneeyam of Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri (a possible senior contemporary of Ezhuthachan).[12]

- A. R. Kattayattu Govindra Menon cites the Kali chronogram 'pavitramparam saukhyam' as a reference to the date of Ezuthachan 's samadhi.[12]

- Chittur Gurumadhom authorities also cites the chronogram 'pavitramparam saukhyam' as a reference to the date of Ezuthachan 's samadhi.[12] The word 'surya' is sometimes suffixed to the chronogram.[12]

- R. Narayana Panikkar supports Govinda Pillai's date (the fifteenth or sixteenth century).[12] The date is based on Ezhuthachan's contemporaneity with Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri (whom he dates to c. 1531 – c. 1637 AD).[12] He also mentions certain Nilakantan "Nambudiri ", a possible senior contemporary of Ezhuthachan (fl. c. 1565 and c. 1601 AD).[12]

- P. K. Narayana Pillai cites a Kali chronogram 'nakasyanyunasaukhyam' or 1555 AD (from a verse relating to the founding of the matham of Chittur) on the date of Ezhuthachan.[12] He dates Nilakanthan, the possible master of Ezhuthachan, to c. 1502 AD.[12]

- Poet-turned-historian Ulloor S. Parameshwara Iyer has argued that Ezhuthachan was born in 1495 AD and lived up to 1575 AD[13]

- A time frame similar to Ulloor was proposed by scholar C. Radhakrishnan.[13]

- Scholar Sheldon Pollock dates Ezuthachan to the sixteenth century.[2]

- Rich Freeman dates Ezhuthachan to late sixteenth-early seventeenth century.[14]

Life and career

The Sankrit literature was, after this [translation by Ezhuthachan] no longer a secret, and there was perhaps no part of South India where it was more studied by people of many castes during the eighteenth century.

— Arthur C. Burnell (1874), Elements of South-Indian Palæography

Biography

Little is known with certainty about Ezhuthachan's life.[1]

Ezhuthachan was born at Trikkandiyoor, near the modern-day town of Tirur, in northern Kerala.[5] It is known that his lineage home was "Thunchaththu".[4] His parents' names are not known, and there are disputes about his given name as well.[1] The name Ezhuthachan, meaning Father of Letters, was a generic title for any village schoolteacher in premodern Kerala.[3]

As a boy he seems to have exhibited uncommon intelligence.[15] He was probably educated by his elder brother (early in his life).[6] After his early education he is believed to have travelled in the other parts of India (outside Kerala) and learned Sanskrit and some other Dravidian languages.[15]

It is believed that Ezhuthachan on his way back from Tamil Nadu had a stopover at Chittur (in Palakkad) and in due course settled down at Thekke Gramam near Anikkode with his disciples. A hermitage (the "Ramananda ashrama") and a Brahmin residence (agraharam), at a site now known as the Chittur Gurumadhom, were established by him (on a piece of land bought from the landlord of Chittur).[4] The institution was flanked by temples of gods Rama and Siva.[16][17] It probably housed both Brahmin and Sudra students.[1] The street still has an array of agraharas (where the twelve Brahmin families migrated along with Ezhuthachan live).[16][17]

Ezhuthachan was eventually associated with an institutional line of masters (gurus).[4] The locale and lineage of these masters can be historically verified.[3] He and his disciples seem to have ignited a whole new literary movement in Kerala.[1] Its style and content nearly overshadowed the earlier Sanskrit poetry.[1] He is believed to have attained samadhi at the Gurumadhom at Chittur.[10] A verse chanted by the ascetics of the mathom during their daily prayers makes a reference to the following line of masters.[18]

- Thunchaththu Sri Guru

- Sri Karunakaran

- Sri Suryanarayanan

- Sri Deva Guru

- Sri Gopala Guru

Myths and legends

- Legends consider Ezhuthachan as a "gandharva" (divine being) who in his previous birth was a witness to the Great War in the Mahabharata.[19]

- As a young boy Ezhuthachan corrected the Brahmins at Trikkandiyoor Temple.[19]

- The Brahmins grew uneasy and gave the boy some plantains to eat, and as a resulting inebriety the boy lost his speech.[19] To counteract this Ezhuthachan's father gave him palm beverage and the boy had his speech restored.[19] Ezhuthachan remained addicted to intoxicants.[19]

- Saraswati, the Goddess of Learning and Arts, is believed to have helped him to complete the Devi Mahatmya.[19]

- Ezhuthachan is credited with endowing a monkey with the gift of speech.[19]

- It is believed that the Raja of Ambalappuzha requested him to decipher a Telugu manuscript on Adhyatma Ramayanam.[19]

- It is also said that Ezhuthachan had a young daughter, who copied his works for the first time.[20][21][22]

- Ezhuthachan or his follower Suryanarayanan predicted the downfall of zamorin's family (the then rulers of Calicut). And the zamorin sought his help to perform a Sakteya Puja.[23]

- It is said that Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri sought the advice of Ezhuthachan on how to start his Narayaneeyam.[13]

Contributions

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Ezhuthachan—although he lived around sixteenth century AD—has been called the "father of modern Malayalam", or, alternatively, the "father of Malayalam literature". His success even in his own lifetime seems to have been great.[5] No original compositions are attributed to Ezhuthachan.[5] His main works generally are based on Sanskrit compositions.[5] Linguists are unanimous in assigning Adhyatma Ramayanam and Sri Mahabharatam to Ezhuthachan. The Ramayanam—the most popular work—depicts the hero, Rama, an ideal figure both as man and god.[5][1][3] Sri Mahabharatam omits all episodes not strictly relevant to the story of the Pandavas and is generally considered as a work of greater literary merit than the Ramayanam.[5][1] However, there is no unanimity among the scholars about the authorship of certain other works generally ascribed to him.[5][3] These include the Brahmanda Puranam, Uttara Ramayanam, Devi Mahatmyam, and Harinama Kirtanam.[24]

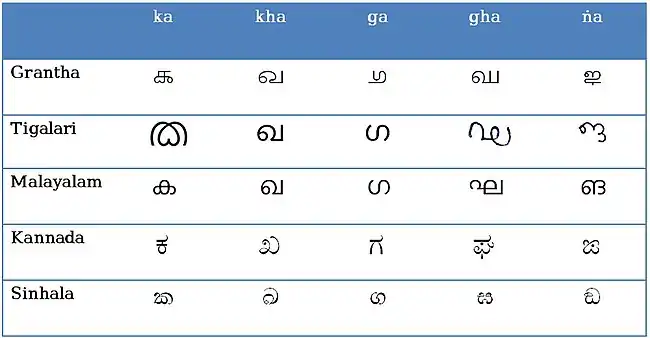

Ezhuthachan's other major contribution has been in mainstreaming (the current) Malayalam alphabet (derived chiefly from the Sanskrit Grantha, or the Arya Script) as the replacement for the old Vattezhuthu (the then-30-letter script of Malayalam).[5][2] The Arya script permitted the free use of Sanskrit in Malayalam writing.[5]

Ezhuthachan movement

I would not at all rule out a level of critique of the prevailing religious order of [Kerala] society, though only implicit and certainly not overtly pitched in caste or class terms, in Eluttacchan's sectarian teachings. It is quite possible, for instance, for Eluttacchan to have been defending the religious potency of his literary form against those who might be deaf to its message, without thereby singling out Brahmanical Sanskritic and priestly religious forms for attack.

Ezhuthachan introduced a movement of domesticated religious textuality in Kerala.[3] He was a significant voice of the Bhakti movement in south India.[3] The Bhakti movement was a collective opposition to Brahmanical excesses and the moral and political decadence of the then-Kerala society.[3] The shift of literary production in Kerala to a largely Sanskritic, puranic religiosity is attributed this movement.[3] Ezhuthachan's school promoted popular and non-Brahman (Bhakti) literary production.[4][3] His works were also a general opposition against the moral decadence of the 16th century Kerala society.[25][3]

Father of Modern Malayalam

The Middle Malayalam (Madhyakaala Malayalam) was succeeded by Modern Malayalam (Aadhunika Malayalam) by 15th century CE.[26] The poem Krishnagatha written by Cherusseri Namboothiri, who was the court poet of the king Udaya Varman Kolathiri (1446 – 1475) of Kolathunadu, is written in modern Malayalam.[27] The language used in Krishnagatha is the modern spoken form of Malayalam.[27] During the 16th century CE, Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan from the Kingdom of Tanur and Poonthanam Nambudiri from the Kingdom of Valluvanad followed the new trend initiated by Cherussery in their poems. The Adhyathmaramayanam Kilippattu and Mahabharatham Kilippattu written by Ezhuthachan and Jnanappana written by Poonthanam are also included in the earliest form of Modern Malayalam.[27]

It is Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan who is also credited with the development of Malayalam script into the current form through the intermixing and modification of the erstwhile scripts of Vatteluttu, Kolezhuthu, and Grantha script, which were used to write the inscriptions and literary works of Old and Middle Malayalam.[27] He further eliminated excess and unnecessary letters from the modified script.[27] Hence, Ezhuthachan is also known as The Father of modern Malayalam.[27] The development of modern Malayalam script was also heavily influenced by the Tigalari script, which was used to write the Tulu language, due to the influence of Tuluva Brahmins in Kerala.[27] The language used in the Arabi Malayalam works of 16th-17th century CE is a mixture of Modern Malayalam and Arabic.[27] They follow the syntax of modern Malayalam, though written in a modified form of Arabic script, which is known as Arabi Malayalam script.[27]

P. Shungunny Menon ascribes the authorship of the medieval work Keralolpathi, which describes the Parashurama legend and the departure of the final Cheraman Perumal king to Mecca, to Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan.[28]

Adhyatma Ramayanam

Adhyatma Ramayanam, written in the parrot-song style, is Ezhuthachan's principle work.[1] It is not an adaptation from the original Valmiki Ramayana, but a translation of the Adhyatma Ramayana, a Sanskrit text connected with the Ramanandi sect.[3] The poem is composed in nearly-modern Malayalam.[3] It depicts Rama, the prince of Ayodhya, as an ideal figure (both as man and god-incarnate, the Bhakti interpretation).[29][1]

The text spread with phenomenal popularity throughout Kerala middle-caste homes as a material for domestic devotional recitation.[3] Throughout the Malayalam month of Karkkidakam, Adhyatma Ramayanam is still recited—as a devotional practice—in the middle-caste homes of Kerala.[30]

But it is worth listening when the later tradition assigns a primal role to Eluttacchan. It tells us something about the place of this multiform narrative, the Ramayana, in constituting the core of a literary tradition; about the enduring historical importance of the moment when a subaltern social formation achieved the literacy that in the South Asian world conditioned the culturally significant type of textuality we may call literature; and about literature as requiring, in the eyes of many readers and listeners, a particular linguistic register, in this case, the highly Sanskritized.

— Sheldon Pollock, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia (2003)

According to critic K. Ayyappa Panicker, those who see Adhyatma Ramayanam merely as a devotional work "belittle" Ezhuthachan.[30]

Style

Parrot-song style

- Known in Malayalam as the Kilippattu genre.[14]

- A convention Ezhuthachan adapted from Old Tamil.[1]

- Recited to a poet by a parrot (the frame of the parrot-narrator).[14]

- Thematic focus: epic or Puranic traditions.[14]

- Intended for recitation or singing.[14]

Lexicon and grammar

- Heavily Sanskritic lexicon with many Sanskrit nominal terminations (lexical distinctions between Manipravalam and the Pattu styles are not visible).[14][1]

- No Sanskrit verbal forms or long compounds.[14]

- Most of the grammatical structures are in Malayalam (the frame of the parrot-narrator and the constituent meters).[14]

- Assembled in an array of Dravidian meters (in simple metrical couplets).[14][1]

Caste

Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan's caste is arguable. It is only known that he belonged to a lower caste (Shudra or Shudra-grade).[2][3][1]

The two most popular opinions are Ezhuthachan and Nair, with Kaniyar being less popular.[31]

Ezhuthachan

Ezhuthachan caste is a socio-economic caste of village school teachers.

According to Arthur C. Burnell, Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan belonged to the Ezhuthachan or "school master" caste.[32] Writer K. Balakrishna Kurup also reports the same, in his book Viswasathinte Kanappurangal.[33] E. P. Bhaskara Guptan, a writer and independent researcher of local history from Kadampazhipuram; supports Kurup's conclusion.[34] Historian Velayudhan Panikkassery expresses the same opinion.[35]

Nair

The Chakkala Nair caste had the rights to enter brahmanical temples and to participate in worships.

The Malayalam poet and historian Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer agree that Ezhuthachan belonged to this caste and conclude that he could be Vattekattu Nair because he visited brahmanical temples and engaged in worship, which is not allowed for the Ezuthacan caste.

William Logan, officer of the Madras Civil Service under the English India Company Government, expresses a similar opinion in his Malabar Manual and states that Thunchaththu Ezuthachan was "a man of Sudra (Nayar) caste".[11] Kottarathil Shankunni wrote in his Aithihyamala that the term Ezhuthachan is nothing but a title taken up by school teachers belonging to several castes[36] mainly by Nairs in Northern kerala indicating that Ezhuthachan was a Nair.

Kaniyar

Some sources consider him to be Kaniyar.[37][38][39][40] This community of traditional astrologers were well versed in Sanskrit and Malayalam.[41][42] During the medieval period, when non-Brahmins were not permitted to learn Sanskrit, only the Kaniyar community had been traditionally enjoying the privilege for accessing and acquiring knowledge in Sanskrit, through their hereditary system of pedagogy. They were learned people and had knowledge in astrology, mathematics, mythology and Ayurveda.[41] They were generally assigned as preceptors of martial art and literacy.[39][43]

In addition to the common title Panicker, the members of Kaniyar from the South Travancore and Malabar region were known as Aasaan, Ezhuthu Aasans, or Ezhuthachans (Father of Letters),[43] by virtue of their traditional avocational function as village school masters to non-Brahmin pupils.[39]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

The parrot-song genre, pioneered by Ezhuthachan, inaugurated the production of many similar works in Malayalam.[14]

The highest literary honour awarded by the Government of Kerala is known as the "Ezhuthachan Puraskaram".[44] Sooranad Kunjan Pillai was the first recipient of the honour (1993).[45] The Malayalam University, established by Kerala Government in 2012, is named after Ezhuthachan.

Initiation to Letters

The sand from the compound where the house of Ezhuthachan stood once is considered as sacred.[10] It is a tradition in north Kerala to practise the art of writing in the beginning on the sand with the first finger.[10]

Monuments

- Ezhuthachan was born at Trikkandiyoor in northern Kerala.[5] His birthplace is now known as Thunchan Parambu.[13]

- Chittur Gurumadhom is located near present-day Palakkad. The madhom is flanked by temples of gods Rama and Siva. The street has an array of agraharas (where the twelve Brahmin families who migrated along with Ezhuthachan live).[16]

- Ezhuthachan's samadhi is also situated at Chittur (in Palakkad).[13]

Relics

- Some relics of Ezhuthachan or his age were sacredly preserved at the Chittur madhom.[5] This included the original manuscripts and the clogs used by him.[5] These artifacts were destroyed in a fire 30 or 40 years before William Logan. Only the Bhagavatam was saved from the fire.[5]

- Scholar A. C. Burnell examined this Bhagavatam (and a stool, clogs and a staff) in the late 19th century. These objects probably belongd to one of the first followers of Ezhuthachan.[5]

- Stool, clog and the staff (seen by Burnell) were destroyed in a second fire. This fire destroyed the original Bhagavatam also.[5]

- Copies of a sri chakra and the idols worshipped by Ezhuthachan, the stylus, the wooden slippers, and a few old manuscripts are exhibited for visitors at Chittur madhom.[17]

See also

References

- Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003). "The Literature of Hinduism in Malayalam". The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. New Delhi: Blackwell Publishing, Wiley India. pp. 173–74. doi:10.1002/9780470998694. ISBN 9780470998694.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2003). "Introduction". In Pollock, Sheldon (ed.). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 479–81. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 481. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Logan, William (2010) [1887]. Malabar. Vol. I. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 92–94.

- Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 482. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. pp. 57–58.

- Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 481–82. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Burnell, Arthur Coke (1874). Elements of South-Indian Palæography. London: Trubner & Co. pp. 35–36.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. p. 47.

- Logan, William (1951) [1887]. Malabar. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. p. 92.

It was no less than a revolution when in the seventeenth century one Tunjatta Eluttachchan, a man of Sudra (Nayar) caste, boldly made an alphabet—the existing Malayalam one—derived chiefly from the Grantha—the Sanskrit alphabets of the Tamils, which permitted of the free use of Sanskrit in writing—and boldly set to work to render the chief Sanskrit poems into Malayalam.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. pp. 61–64.

- Times News Network (5 July 2003). "Ezhuthachan - Father of Literary Tradition in Malayalam". The Times of India (Mumbai ed.). Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Freeman, Rich (2003). "Genre and Society: The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. p. 480. ISBN 9780520228214.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta Menon (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. p. 49.

- Prabhakaran, G. (14 June 2011). "Thunchath Ezhuthachan's Memorial Starved of Funds". The Hindu (Kerala ed.). Palakkad. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Prabhakaran, G. (13 October 2013). "Ezhuthachan's Abode Needs a Prop". The Hindu (Kerala ed.). Palakkad.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. p. 55.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. pp. 45–46.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. p. 47.

This family according to tradition is that of Ezuttaccan's wife. Whether Ezuttaccan had a wife or not is still a disputed point.

- Burnell, Arthur Coke (1874). Elements of South-Indian Palæography. London: Trubner & Co. p. 35.

Tunjatta Eluttacchan's paraphrases were copied, it is said, by his daughter.

- Logan, William (2010) [1887]. Malabar. Vol. I. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 92.

It is said that as Tunjatta Eluttachchan lay on his death-bed he told his daughter that at a particular hour, on a particular day, in a certain month and a certain year which he named a youth would come to his house.

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. p. 46.

It would appear that he [Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan] predicted that the Zamorin's family would lose their ruling rights in the third generation after that. According to some it is Suryanarayanan who predicted the downfall of Zamorins

- Menon, Chelnat Achyuta (1940). Ezuttaccan and His Age. Madras: University of Madras. pp. xiii.

- Narayanan, M. G. S (2017). Keralam: Charithravazhiyile Velichangal കേരളം ചരിത്രവഴിയിലെ വെളിച്ചങ്ങൾ (in Malayalam). Kottayam: Sahithya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society. p. 106. ISBN 978-93-87439-08-5.

കവിതയുടെ ഇന്ദ്രജാലത്തിലൂടെ നിരക്ഷരകുക്ഷികളായ നായർപ്പടയാളിക്കൂട്ടങ്ങൾക്ക് രാമായണഭാരതാദി കഥകളിലെ നായികാനായകന്മാരെ നാട്ടിലെ അയൽവാസികളെപ്പോലെ പരിചയപ്പെടുത്തുവാൻ എഴുത്തച്ഛനു സാധിച്ചു. ആര്യസംസ്കാരത്തിലെ ധർമശാസ്ത്രമൂല്യങ്ങൾ മലയാളികളുടെ മനസ്സിൽ അദ്ദേഹം ശക്തമായി അവതരിപ്പിച്ചു. ലൈംഗികാരാജകത്വം കൂത്താടിയ ശൂദ്രസമുദായത്തിൽ പാതിവൃത്യമാതൃകയായി സീതാദേവിയെ പ്രതിഷ്ഠിക്കുവാനും പിതൃഭക്തി, ഭ്രാതൃസ്നേഹം, ധാർമ്മികരോഷം മുതലായ സങ്കല്പങ്ങൾക്ക് ഭാഷയിൽ രൂപം കൊടുക്കാനും എഴുത്തച്ഛനു സാധിച്ചു. അതിനുമുമ്പ് ബ്രാഹ്മണരുടെ കുത്തകയായിരുന്ന പൗരാണികജ്ഞാനം ബ്രാഹ്മണേതരസമുദായങ്ങൾക്കിടയിൽ പ്രചരിപ്പിച്ചതിലൂടെ ആര്യ-ദ്രാവിഡ സമന്വയത്തിന്റെ സൃഷ്ടിയായ ആധൂനിക മലയാളഭാഷയും സംസ്കാരവും കേരളത്തിനു സ്വായത്തമാക്കുവാൻ എഴുത്തച്ഛന്റെ പള്ളിക്കൂടമാണ് സഹായിച്ചത്. ഓരോ തറവാട്ടിലും രാമായണാദി പുരാണേതിഹാസഗ്രന്ഥങ്ങളുടെ താളിയോലപ്പകർപ്പുകൾ സൂക്ഷിക്കുവാനും ധനസ്ഥിതിയുള്ളേടത്ത് എഴുത്തച്ഛന്മാരെ നിശ്ചയിച്ച് പള്ളിക്കൂടങ്ങൾ സ്ഥാപിക്കുവാനും അങ്ങനെ കേരളത്തിൽ ജനകീയസാക്ഷരതക്ക് തുടക്കംകുറയ്ക്കുവാനും എഴുത്തച്ഛന്റെ പ്രയത്നമാണ് വഴിവെച്ചത്. അതിന്റെ ഫലമായി പാരായണത്തിലൂടെയും കേൾവിയിലൂടെയും വളർന്ന സംസ്കാരമാണ് കേരളത്തിന് ഭാരതസംസ്കാരത്തിലേക്ക് എത്തിനോക്കാൻ ഒരു കിളിവാതിൽ സമ്മാനിച്ചത്.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Dr. K. Ayyappa Panicker (2006). A Short History of Malayalam Literature. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Information and Public Relations, Kerala.

- History of Travancore by Shungunny Menon, page 28

- Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003). "The Literature of Hinduism in Malayalam". The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. New Delhi: Blackwell Publishing, Wiley India. p. 173. doi:10.1002/9780470998694. ISBN 9780470998694.

- Santhosh, K. (14 July 2014). "When Malayalam Found its Feet". The Hindu (Kerala ed.).

- K. S., Aravind (9 September 2014). "'Caste'ing a Shadow on the Legacy of Ezhuthachan". The New Indian Express (Kerala ed.). Kerala. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Burnell, Arthur Coke (1878). Elements of South Indian Paleography (2nd ed.). Ludgate Hill, London: Trubner & Co. p. 42.

The application of the Arya-eluttu to the vernacular Malayalam was the work of a low-caste man who goes under the name of Tunjatta Eluttacchan, a native of Trikkandiyur in the present district of Malabar. He lived in the seventeenth century, but his real name is forgotten; Tunjatta being his 'house' or family-name, and Eluttacchan (=schoolmaster) indicating his caste.

- Kurup, K. Balakrishna (January 2000) [May 1998]. Vishwasathinte Kanappurangal (2nd ed.). Mathrubhumi Publications. p. 24.

മലബാർ ഭാഗത്ത് വിദ്യാഭ്യാസ പ്രചാരണത്തിൽ എഴുത്തച്ഛൻമാർ മുന്നിട്ടിറങ്ങിയപ്പോൾ തിരുവിതാംകൂർ ഭാഗത്തു ഗണകന്മാർ ആ ദൗത്യം നിർവഹിച്ചു. എഴുത്തച്ഛന്മാർ വട്ടെഴുത്ത് പ്രചരിപ്പിച്ചതു മൂലവും മലയാളത്തിലെ രാമായണാദി ഗ്രന്ഥങ്ങൾ വട്ടെഴുത്തിൽ (ഗ്രന്ഥാക്ഷരത്തിൽ) എഴുതപ്പെട്ടത് മൂലവുമാവാം തുഞ്ചത്തെഴുത്തച്ഛനാണ് മലയാളഭാഷയുടെ പിതാവ് എന്ന് പറഞ്ഞുവരാൻ ഇടയായത്. ഭക്തി പ്രസ്ഥാനത്തിന്റെ പ്രേരണക്ക് വിധേയമായി രാമായണമെഴുതിയ കണ്ണശ്ശൻ ഗണകവംശത്തിലും (പണിക്കർ) അധ്യാത്മരാമായണം രചിച്ച തുഞ്ചൻ എഴുത്തച്ഛൻ വംശത്തിലും പെട്ടവരായിരുന്നുവെന്നത് യാദൃശ്ചിക സംഭവമല്ല.

- Guptan, E. P. Bhaskara (2013) [2004]. Deshayanam: Deshacharithrakathakal (2nd ed.). Kadampazhipuram, Palakkad: Samabhavini Books. p. 47.

തുഞ്ചൻ കടുപ്പട്ട-എഴുത്തച്ഛനായിരുന്നുവെന്ന് ശ്രീ. കെ. ബാലകൃഷ്ണക്കുറുപ്പ് വാദിക്കുന്നു. ആചാര്യൻ ചക്കാലനായർ വിഭാഗമായിരുന്നുവെന്നാണ് പണ്ട് പരക്കെ ധരിച്ചിരുന്നത്. അങ്ങനെയായിരുന്നാൽ പോലും അദ്ദേഹം ജനിതകമായി കടുപ്പട്ട-എഴുത്തച്ഛനല്ല എന്ന് വന്നുകൂടുന്നില്ല.

- Sankunni, Kottarathil (1 August 2009). Eithihyamala (in Malayalam) (2nd ed.). Kottayam: D. C. Books. ISBN 978-8126422906.

- Pillai, Govinda Krishna. Origin and Development of Caste. pp. 103 & 162.

- Sadasivan, S. N. A Social History of India. p. 371.

- Pillay, Kolappa; Pillay, Kanaka Sabhapathi. Studies in Indian history: with Special Reference to Tamil Nadu. p. 103.

- Pillai, G. K. (1959). India Without Misrepresentation: Origin and Development of Caste. Vol. III. Allahabad: Kitab Mahal. p. 162.

- Thurston, Edgard; Rangachari, K. (2001). Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. I. p. 186.

- Bhattacharya, Ranjit Kumar; Das, Nava Kishor (1993). Anthropological Survey of India: Anthropology of Weaker Sections. p. 590.

- Raja, Dileep. G (2005). "Of an Old School of Teachers". The Hindu. Thiruvananthapuram. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

- "M. K. Sanoo wins Ezhuthachan Award". The Hindu (Kochi ed.). 2 November 2013.

- United News of India (8 November 2011). "Ezhuthachan Puraskaram for M. T. Vasudevan Nair". Mathrubhumi. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

External links

- "Eluttaccan and His Age" (1940) by C. Achyuta Menon (Madras: University of Madras).

- "Adhyatma Ramayanam Kilippattu", "Sri Mahabharatam Kilippattu" University of Tubingen, Germany (a manuscript of 1870)