FLiBe

FLiBe is the name of a molten salt made from a mixture of lithium fluoride (LiF) and beryllium fluoride (BeF2). It is both a nuclear reactor coolant and solvent for fertile or fissile material. It served both purposes in the Molten-Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The 2:1 molar mixture forms a stoichiometric compound, Li2[BeF4] (lithium tetrafluoroberyllate), which has a melting point of 459 °C, a boiling point of 1430 °C, and a density of 1.94 g/cm3.

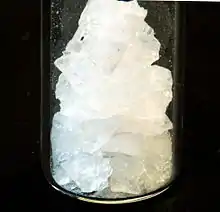

Its volumetric heat capacity is similar to that of water (4540 kJ/(m3·K) = 1085 kcal/(m3·K)): 8.5% more than the standard value considered for water at room temperature), more than four times that of sodium, and more than 200 times that of helium at typical reactor conditions.[1] Its specific heat capacity is 2414.17 J/(kg·K), or about 60% that of water.[2] Its appearance is white to transparent, with crystalline grains in a solid state, morphing into a completely clear liquid upon melting. However, soluble fluorides such as UF4 and NiF2, can dramatically change the salt's color in both solid and liquid state. This made spectrophotometry a viable analysis tool, and it was employed extensively during the MSRE operations.[3][4][5]

The eutectic mixture is slightly greater than 50% BeF2 and has a melting point of 360 °C.[6] This mixture was never used in practice due to the overwhelming increase in viscosity caused by the BeF2 addition in the eutectic mixture. BeF2, which behaves as a glass, is only fluid in salt mixtures containing enough molar percent of Lewis base. Lewis bases, such as the alkali fluorides, will donate fluoride ions to the beryllium, breaking the glassy bonds which increase viscosity. In FLiBe, beryllium fluoride is able to sequester two fluoride ions from two lithium fluorides in a liquid state, converting it into the tetrafluoroberyllate ion [BeF4]2−.[7]

Chemistry

The chemistry of FLiBe, and other fluoride salts, is unique due to the high temperatures at which the reactions occur, the ionic nature of the salt, and the reversibility of many of the reactions. At the most basic level, FLiBe melts and complexes itself through

This reaction occurs upon initial melting. However, if the components are exposed to air they will absorb moisture. This moisture plays a negative role at high temperature by converting BeF2, and to a lesser extent LiF, into an oxide or hydroxide through the reactions

and

- BeF2(l) + H2O(g) ⇌ BeO(d) + 2 HF(d).

While BeF2 is a very stable chemical compound, the formation of oxides, hydroxides, and hydrogen fluoride reduce the stability and inertness of the salt. This leads to corrosion. Its important to understand that all dissolved species in these two reactions cause the corrosion—not just the hydrogen fluoride. This is because all dissolved components alter the reduction potential or redox potential. The redox potential is an innate and measurable voltage in the salt which is the prime indicator of the corrosion potential in salt. Usually, the reaction

is set at zero volts. This reaction proves convenient in a laboratory setting and can be used to set the salt to zero through bubbling a 1:1 mixture of hydrogen fluoride and hydrogen through the salt. Occasionally the reaction:

is used as a reference. Regardless of where the zero is set, all other reactions which occur in the salt will occur at predictable, known voltages relative to the zero. Therefore, if the redox potential of the salt is close to a specific reaction's voltage, that reaction can be expected to be the predominant reaction. Therefore, it is important to keep a salt's redox potential far away from reactions which are undesirable. For example, in a container alloy of nickel, iron, and chromium, the reactions of concern would be the fluorination of container and subsequent dissolution of these metal fluorides. The dissolution of the metal fluorides then alters the redox potential. This process continues until an equilibrium between metals and salt is reached. It is essential that a salt's redox potential be kept as far away from fluorination reactions as possible, and that metals in contact with salt be as far away from the salt's redox potential as possible in order to prevent excessive corrosion.

The easiest method to prevent undesirable reactions is to pick materials whose reaction voltages are far from the redox potential of the salt in the salt's worst case. Some of these materials are tungsten, carbon, molybdenum, platinum, iridium, and nickel. Of all these materials, only two are affordable and weldable: nickel and molybdenum. These two elements were chosen as the main portion of Hastelloy-N, the material of the MSRE.

Altering the redox potential of FLiBe can be done in two ways. First, the salt can be forced by physically applying a voltage to the salt with an inert electrode. The second, more common way, is to perform a chemical reaction in the salt which occurs at the desired voltage. For example, redox potential can be altered by sparging hydrogen and hydrogen fluoride into the salt or by dipping a metal into the salt.

Coolant

As a molten salt it can serve as a coolant which can be used at high temperatures without reaching a high vapor pressure. Notably, its optical transparency allows easy visual inspection of anything immersed in the coolant as well as any impurities dissolved in it. Unlike sodium or potassium metals, which can also be used as high-temperature coolants, it does not violently react with air or water. FLiBe salt has low hygroscopy and solubility in water.[8]

Nuclear properties

The low atomic weight of lithium, beryllium and to a lesser extent fluorine make FLiBe an effective neutron moderator. As natural lithium contains ~7.5% lithium-6, which tends to absorb neutrons producing alpha particles and tritium, nearly pure lithium-7 is used to give the FLiBe a small neutron absorption cross section;[9] e.g. the MSRE secondary coolant was 99.993% lithium-7 FLiBe.[10] When Li-7 does absorb a neutron, it nigh-instantaneously decays via successive beta- and then alpha decay into a beta particle and two alpha particles.

Beryllium will occasionally disintegrate into two alpha particles and two neutrons when hit by a fast neutron. Fluorine has a non-negligible cross section for (α,n) reactions, which needs to be taken into account when calculating neutronics.[11]

Applications

In the liquid fluoride thorium reactor (LFTR) it serves as solvent for the fissile and fertile material fluoride salts, as well as moderator and coolant.

Some other designs (sometimes called molten-salt cooled reactors) use it as coolant, but have conventional solid nuclear fuel instead of dissolving it in the molten salt.

The liquid FLiBe salt was also proposed as a liquid blanket for tritium production and cooling in the ARC fusion reactor, a compact tokamak design by MIT.[12]

References

- http://www.ornl.gov/~webworks/cppr/y2001/pres/122842.pdf Archived 2010-01-13 at the Wayback Machine CORE PHYSICS CHARACTERISTICS AND ISSUES FOR THE ADVANCED HIGH-TEMPERATURE REACTOR (AHTR), Ingersoll, Parma, Forsberg, and Renier, ORNL and Sandia National Laboratory

- https://inldigitallibrary.inl.gov/sites/STI/STI/5698704.pdf Engineering Database of Liquid Salt Thermophysical and Thermochemical Properties

- Toth, L. M. (1967). Containers for Molten Fluoride Spectroscopy.

- Phillip Young, Jack; Mamantov, Gleb; Whiting, F. L. (1967). "Simultaneous voltammetric generation of uranium(III) and spectrophotometric observation of the uranium(III)-uranium(IV) system in molten lithium fluoride-beryllum fluoride-zirconium fluoride". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 71 (3): 782–783. doi:10.1021/j100862a055.

- Young, J. P.; White, J. C. (1960). "Absorption Spectra of Molten Fluoride Salts. Solutions of Several Metal Ions in Molten Lithium Fluoride-Sodium Fluoride-Potassium Fluoride". Analytical Chemistry. 32 (7): 799–802. doi:10.1021/ac60163a020.

- Williams, D. F., Toth, L. M., & Clarno, K. T. (2006). Assessment of Candidate Molten Salt Coolants for the Advanced High-Temperature Reactor (AHTR). Tech. Rep. ORNL/TM-2006/12, Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

- Toth, L. M.; Bates, J. B.; Boyd, G. E. (1973). "Raman spectra of Be2F73- and higher polymers of beryllium fluorides in the crystalline and molten state". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 77 (2): 216–221. doi:10.1021/j100621a014.

- "Engineering Database of Liquid Salt Thermophysical and Thermochemical Properties" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2014.

- "The Pea and the Beach-Ball – Energy From Thorium". 28 September 2010.

- "In Czech: ORNL part of nuclear R&D pact". Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- https://www.oecd-nea.org/janisweb/book/alphas/F19/MT4/renderer/226%5B%5D

- Sorbom, B.N. (2015). "ARC: A compact, high-field, fusion nuclear science facility and demonstration power plant with demountable magnets". Fusion Engineering and Design. 100: 378–405. arXiv:1409.3540. doi:10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.07.008. S2CID 1258716.