Golden Fleece

In Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece (Greek: Χρυσόμαλλον δέρας, Chrysómallon déras, literally, Golden-haired pelt) is the fleece of the golden-woolled,[lower-alpha 1] winged ram, Chrysomallos, that rescued Phrixus and brought him to Colchis, where Phrixus then sacrificed it to Zeus. Phrixus gave the fleece to King Aeëtes who kept it in a sacred grove, whence Jason and the Argonauts stole it with the help of Medea, Aeëtes' daughter. The fleece is a symbol of authority and kingship.

In the historical account, the hero Jason and his crew of Argonauts set out on a quest for the fleece by order of King Pelias in order to place Jason rightfully on the throne of Iolcus in Thessaly. Through the help of Medea, they acquire the Golden Fleece. The story is of great antiquity and was current in the time of Homer (eighth century BC). It survives in various forms, among which the details vary.

Nowadays, the heraldic variations of the Golden Fleece are featured frequently in Georgia, especially for Coats of Arms and Flags associated with Western Georgian (Historical Colchis) municipalities and cities, including the Coats of Arms of City of Kutaisi, the ancient capital city of Colchis.

Plot

| Part of a series on |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

_02.jpg.webp) |

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

Athamas the founder of Thessaly, but also king of the city of Orchomenus in Boeotia (a region of southeastern Greece), took the goddess Nephele as his first wife. They had two children, the boy Phrixus (whose name means "curly," as in the texture of the ram's fleece) and the girl Helle. Later Athamas became enamored of and married Ino, the daughter of Cadmus. When Nephele left in anger, drought came upon the land.

Ino was jealous of her stepchildren and plotted their deaths; in some versions, she persuaded Athamas that sacrificing Phrixus was the only way to end the drought. Nephele, or her spirit, appeared to the children with a winged ram whose fleece was of gold.[lower-alpha 2] The ram had been sired by Poseidon in his primitive ram-form upon Theophane, a nymph[lower-alpha 3] and the granddaughter of Helios, the sun-god. According to Hyginus,[2] Poseidon carried Theophane to an island where he made her into a ewe so that he could have his way with her among the flocks. There Theophane's other suitors could not distinguish the ram-god and his consort.[3]

Nephele's children escaped on the yellow ram over the sea, but Helle fell off and drowned in the strait now named after her, the Hellespont. The ram spoke to Phrixus, encouraging him,[lower-alpha 4] and took the boy safely to Colchis (modern-day Georgia), on the easternmost shore of the Euxine (Black) Sea. There the ram was sacrificed to gods. In essence, this act returned the ram to the god Poseidon, and the ram became the constellation Aries.

Phrixus settled in the house of Aeetes, son of Helios the sun god. He hung the Golden Fleece preserved from the ram on an oak in a grove sacred to Ares, the god of war and one of the Twelve Olympians. The fleece was guarded by a never-sleeping dragon with teeth that could become soldiers when planted in the ground. The dragon was at the foot of the tree on which the fleece was placed.[5]

In some versions of the story, Jason attempts to put the guard serpent to sleep. The snake is coiled around a column at the base of which is a ram and on top of which is a bird.

Evolution of plot

Pindar employed the quest for the Golden Fleece in his Fourth Pythian Ode (written in 462 BC), though the fleece is not in the foreground. When Aeetes challenges Jason to yoke the fire-breathing bulls, the fleece is the prize: "Let the King do this, the captain of the ship! Let him do this, I say, and have for his own the immortal coverlet, the fleece, glowing with matted skeins of gold".[6]

In later versions of the story, the ram is said to have been the offspring of the sea god Poseidon and Themisto (less often, Nephele or Theophane). The classic telling is the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes, composed in the mid-third century BC Alexandria, recasting early sources that have not survived. Another, much less-known Argonautica, using the same body of myth, was composed in Latin by Valerius Flaccus during the time of Vespasian.

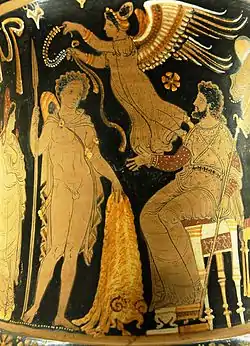

Where the written sources fail, through accidents of history, sometimes the continuity of a mythic tradition can be found among the vase-painters. The story of the Golden Fleece appeared to have little resonance for Athenians of the Classic age, for only two representations of it on Attic-painted wares of the fifth century have been identified: a krater at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a kylix in the Vatican collections.[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6][7] In the kylix painted by Douris, c. 480–470, Jason is being disgorged from the mouth of the dragon, a detail that does not fit easily into the literary sources; behind the dragon, the fleece hangs from an apple tree. Jason's helper in the Athenian vase-paintings is not Medea— who had a history in Athens as the opponent of Theseus—but Athena.

Interpretations

The very early origin of the myth in preliterate times means that during the more than a millennium when it was to some degree part of the fabric of culture, its perceived significance likely passed through numerous developments.

Several euhemeristic attempts to interpret the Golden Fleece "realistically" as reflecting some physical cultural object or alleged historical practice have been made. For example, in the 20th century, some scholars suggested that the story of the Golden Fleece signified the bringing of sheep husbandry to Greece from the east;[lower-alpha 7] in other readings, scholars theorized it referred to golden grain,[lower-alpha 8] or to the Sun.[lower-alpha 9]

A more widespread interpretation relates the myth of the fleece to a method of washing gold from streams, which was well attested (but only from c. 5th century BC) in the region of Georgia to the east of the Black Sea. Sheep fleeces, sometimes stretched over a wooden frame, would be submerged in the stream, and gold flecks borne down from upstream placer deposits would collect in them. The fleeces would be hung in trees to dry before the gold was shaken or combed out. Alternatively, the fleeces would be used on washing tables in alluvial mining of gold or on washing tables at deep gold mines.[lower-alpha 10] Judging by the very early gold objects from a range of cultures, washing for gold is a very old human activity.

Strabo describes the way in which gold could be washed:

It is said that in their country gold is carried down by the mountain torrents, and that the barbarians obtain it by means of perforated troughs and fleecy skins, and that this is the origin of the myth of the golden fleece—unless they call them Iberians, by the same name as the western Iberians, from the gold mines in both countries.

Another interpretation is based on the references in some versions to purple or purple-dyed cloth. The purple dye extracted from the purple dye murex snail and related species was highly prized in ancient times. Clothing made of cloth dyed with Tyrian purple was a mark of great wealth and high station (hence the phrase "royal purple"). The association of gold with purple is natural and occurs frequently in literature.[lower-alpha 11]

Main theories

The following are the chief among the various interpretations of the fleece, with notes on sources and major critical discussions:

- It represents royal power.[8][9][10][11][12]

- It represents the flayed skin of Krios ('Ram'), companion of Phrixus.[13]

- It represents a book on alchemy.[14][15]

- It represents a technique of writing in gold on parchment.[16]

- It represents a form of placer mining practiced in Georgia, for example.[17][18][19][20][21][22]

- It represents the forgiveness of the Gods.[23][24]

- It represents a rain cloud.[25][26]

- It represents a land of golden grain.[26][27]

- It represents the spring-hero.[26][28]

- It represents the sea reflecting the sun.[26][29][30]

- It represents the gilded prow of Phrixus' ship.[26][31]

- It represents a breed of sheep in ancient Georgia.[32][33][34]

- It represents the riches imported from the East.[35]

- It represents the wealth or technology of Colchis.[36][37][38]

- It was a covering for a cult image of Zeus in the form of a ram.[39]

- It represents a fabric woven from sea silk.[40][41][42]

- It is about a voyage from Greece, through the Mediterranean, across the Atlantic to the Americas.[43]

- It represents trading fleece dyed murex-purple for Georgian gold.[44]

See also

- List of mythological objects

- Absyrtus

- Gold mining

- Order of the Golden Fleece

- Gideon, another motif represented with fleece in Christian art

Notes

- Greek: Χρυσόμαλλος, Khrusómallos.

- That the ram was sent by Zeus was the version heard by Pausanias in the second century of the Christian era (Pausanias, ix.34.5).

- Theophane may equally be construed as "appearing as a goddess" or as "causing a god to appear".[1]

- Upon the shield of Jason, as it was described in Apollonius' Argonautica, "was Phrixos the Minyan, depicted as though really listening to the ram, and the ram seemed to be speaking. As you looked on this pair, you would be struck dumb with amazement and deceived, for you would expect to hear some wise utterance from them, with this hope you would gaze long upon them.".[4]

- Vatican 16545

- Gisela Richter published the Metropolitan Museum 's krater in: Richter, Gisela (1935). "Jason and the Golden Fleece". American Journal of Archaeology. 39 (2): 182–84. doi:10.2307/498331. JSTOR 498331.

- Interpretation #12

- Interpretation #8

- Interpretation #10

- Interpretation #5

- Interpretation #17

References

- Karl Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks

- Hyginus, Fabulae, 163

- Karl Kerenyi The Gods of the Greeks, (1951) 1980:182f

- Richard Hunter, tr. Apollonius of Rhodes: Jason and the Golden Fleece, (Oxford University Press) 1993:21)

- William Godwin (1876). Lives of the Necromancers. London, F. J. Mason. p. 41.

- Translation in Nicholson, Nigel (Autumn–Winter 2000). "Polysemy and Ideology in Pindar 'Pythian' 4.229–30". Phoenix. 54 (3/4): 192. doi:10.2307/1089054. JSTOR 1089054..

- King, Cynthia (July 1983). "Who Is That Cloaked Man? Observations on Early Fifth Century B. C. Pictures of the Golden Fleece". American Journal of Archaeology. 87 (3): 385–87. doi:10.2307/504803. JSTOR 504803. S2CID 193032482.

- Marcus Porcius Cato and Marcus Terentius Varro, Roman Farm Management, The Treatises of Cato and Varro, in English, with Notes of Modern Instances

- Braund (1994), pp. 21–23

- Popko, M. (1974). "Kult Swietego runa w hetyckiej Anatolii" [The Cult of the Golden Fleece in Hittite Anatolia]. Preglad Orientalistyczuy (in Russian). 91: 225–30.

- Newman, John Kevin (2001) "The Golden Fleece. Imperial Dream" (Theodore Papanghelis and Antonios Rengakos (eds.). A Companion to Apollonius Rhodius. Leiden: Brill (Mnemosyne Supplement 217), 309–40)

- Lordkipanidze (2001)

- Diodorus Siculus 4. 47; cf. scholia on Apollonius Rhodius 2. 1144; 4. 119, citing Dionysus' Argonautica

- Palaephatus (fourth century BC) 'On the Incredible' (Festa, N. (ed.) (1902) Mythographi Graeca III, 2, Lipsiae, p. 89

- John of Antioch fr.15.3 FHG (5.548)

- Haraxes of Pergamum (c. first to sixth century) (Jacoby, F. (1923) Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker I (Berlin), IIA, 490, fr. 37)

- Strabo (first century BC) Geography I, 2, 39 (Jones, H.L. (ed.) (1969) The Geography of Strabo (in eight volumes) London "Strabo, Geography, NOTICE". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Tran, T (1992). "The Hydrometallurgy of Gold Processing". Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 17 (4): 356–65. Bibcode:1992ISRv...17..356T. doi:10.1179/isr.1992.17.4.356.

- "Gold – during the Classic Era". Minelinks.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Shuker, Karl P. N. (1997), From Flying Toads To Snakes With Wings, Llewellyn

- Renault, Mary (2004), The Bull from the Sea, Arrow (Rand)

- refuted in Braund (1994), p. 24 and Lordkipanidze (2001)

- Müller, Karl Otfried (1844), Orchomenos und die Minyer, Breslau

- refuted in Bacon (1925), pp. 64 ff, 163 ff

- Forchhammer, P. W. (1857) Hellenica Berlin p. 205 ff, 330 ff

- refuted in Bacon (1925)

- Faust, Adolf (1898), Einige deutsche und griechische Sagen im Lichte ihrer ursprünglichen Bedeutung. Mulhausen

- Schroder, R. (1899), Argonautensage und Verwandtes, Poznań

- Vurthiem, V (1902), "De Argonautarum Vellere aureo", Mnemosyne, New Series, XXX, pp. 54–67; XXXI, p. 116

- Wilhelm Mannhardt, in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, VII, p. 241 ff, 281 ff

- Svoronos, M. (1914). Journal International d'Archéologie Numismatique. XVI: 81–152.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Ninck, M. (1921). "Die Bedeutung des Wassers im Kult und Leben der Alten". Philologus Suppl. 14 (2).

- Ryder, M.L. (1991). "The last word on the Golden Fleece legend?". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 10: 57–60. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1991.tb00005.x.

- Smith, G.J.; Smith, A.J. (1992). "Jason's Golden Fleece". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 11: 119–20. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1992.tb00260.x.

- Bacon (1925)

- Akaki Urushadze (1984), The Country of the Enchantress Medea, Tbilisi

- "Untitled Document". Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 13 October 2005.

- "Colchis, The Land Of The Golden Fleece, Republic Of Georgia". Great-adventures.com. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Robert Graves (1944/1945), The Golden Fleece/Hercules, My Shipmate, New York: Grosset & Dunlap

- Verrill, A. Hyatt (1950), Shell Collector's Handbook, New York: Putnam, p. 77

- Abbott, R. Tucker (1972), Kingdom of the Seashell, New York: Crown Publishers, p. 184; "history of sea byssus cloth". Designboom.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- refuted in Barber (1991) and McKinley (1999), pp. 9–29

- Bailey, James R. (1973), The God Kings and the Titans; The New World Ascendancy in Ancient Times, St. Martin's Press

- Silver, Morris (1992), Taking Ancient Mythology Economically, Leiden: Brill "Document Title". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

Bibliography

- Bacon, Janet Ruth (1925). The Voyage of the Argonauts. London: Methuen.

- Barber, Elizabeth J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles: the Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8.

- Braund, David (1994). Georgia in Antiquity: A History of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 BC–AD 562. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814473-1.

- Lordkipanidze, Otar (2001). "The Golden Fleece: myth, euhemeristic explanation and archaeology". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 20 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00121.

- McKinley, Daniel (1999). Pinna and her Silken Beard: a Foray into Historical Misappropriations. Ars Textrina. Vol. 29. Charles Babbage Research Centre.

External links

Media related to Golden Fleece at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Golden Fleece at Wikimedia Commons- The Project Gutenberg text of The Golden Fleece and the Heroes Who Lived Before Achilles