Neomycin

Neomycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that displays bactericidal activity against gram-negative aerobic bacilli and some anaerobic bacilli where resistance has not yet arisen. It is generally not effective against gram-positive bacilli and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. Neomycin comes in oral and topical formulations, including creams, ointments, and eyedrops. Neomycin belongs to the aminoglycoside class of antibiotics that contain two or more amino sugars connected by glycosidic bonds.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Neo-rx |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682274 |

| Routes of administration | Topical, oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | None |

| Protein binding | N/A |

| Metabolism | N/A |

| Elimination half-life | 2 to 3 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.333 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H46N6O13 |

| Molar mass | 614.650 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Neomycin was discovered in 1949 by microbiologist Selman Waksman and his student Hubert Lechevalier at Rutgers University. Neomycin received approval for medical use in 1952.[1] Rutgers University was granted the patent for neomycin in 1957.[2]

Discovery

Neomycin was discovered in 1949 by the microbiologist Selman Waksman and his student Hubert Lechevalier at Rutgers University. It is produced naturally by the bacterium Streptomyces fradiae.[3] Synthesis requires specific nutrient conditions in either stationary or submerged aerobic conditions. The compound is then isolated and purified from the bacterium.[4]

Medical uses

Neomycin is typically applied as a topical preparation, such as Neosporin (neomycin/polymyxin B/bacitracin). The antibiotic can also be administered orally, in which case it is usually combined with other antibiotics. Neomycin is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and has been used as a preventive measure for hepatic encephalopathy and hypercholesterolemia. By killing bacteria in the intestinal tract, Neomycin keeps ammonia levels low and prevents hepatic encephalopathy, especially before gastrointestinal surgery.

Waksman and Lechevalier originally noted that neomycin was active against streptomycin-resistant bacteria as well as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent for tuberculosis.[5] Neomycin has also been used to treat small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Neomycin is not administered via injection, as it is extremely nephrotoxic (damaging to kidney function) even when compared to other aminoglycosides. The exception is when neomycin is included, in small quantities, as a preservative in some vaccines – typically 25 μg per dose.[6]

Spectrum

Similar to other aminoglycosides, neomycin has excellent activity against gram-negative bacteria and is partially effective against gram-positive bacteria. It is relatively toxic to humans, with allergic reactions noted as a common adverse reaction (see: hypersensitivity).[7] Physicians sometimes recommend using antibiotic ointments without neomycin, such as Polysporin.[8] The following represents minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) susceptibility data for a few medically significant gram-negative bacteria.[9]

- Enterobacter cloacae: >16 μg/ml

- Escherichia coli: 1 μg/ml

- Proteus vulgaris: 0.25 μg/ml

Side effects

In 2005–06, Neomycin was the fifth-most-prevalent allergen in patch test results (10.0%).[10] It is also a known GABA gamma-Aminobutyric acid antagonist and can be responsible for seizures and psychosis.[11] Like other aminoglycosides, neomycin has been shown to be ototoxic, causing tinnitus, hearing loss, and vestibular problems in a small number of patients. Patients with existing tinnitus or sensorineural hearing loss are advised to speak with a healthcare practitioner about the risks and side effects prior to taking this medication.

Molecular biology

Activity

Neomycin's antibacterial activity stems from its binding to the 30S subunit of the prokaryotic ribosome, where it inhibits prokaryotic translation of mRNA.[12]

Neomycin also exhibits a high binding affinity for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid component of cell membranes.[13]

Resistance

Neomycin resistance is conferred by either one of two kanamycin kinase genes.[14] Genes conferring neomycin-resistance are commonly included in DNA plasmids used to establish stable mammalian cell lines expressing cloned proteins in culture. Many commercially available protein expression plasmids contain a neo-resistance gene as a selectable marker.

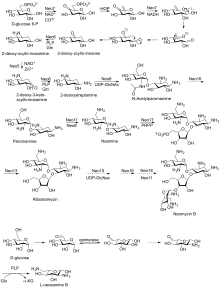

Biosynthetic pathway

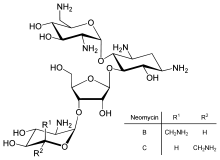

Neomycin was first isolated from the Streptomyces fradiae and Streptomyces albogriseus in 1949 (NBRC 12773).[15] Neomycin is a mixture of neomycin B (framycetin); and its epimer neomycin C, the latter component accounting for some 5–15% of the mixture. It is a basic compound that is most active with an alkaline reaction.[5] It is also thermostable and soluble in water (while insoluble in organic solvents).[5] Neomycin has good activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, but is ototoxic. Its use is thus restricted to the oral treatment of intestinal infections.[16]

Neomycin B is composed of four linked moieties: D-neosamine, 2-deoxystreptamine (2-DOS), D-ribose, and L-neosamine.

Neomycin A, also called neamine, contains D-neosamine and 2-deoxystreptamine. Six genes are responsible for neamine biosynthesis: DOIS gene (btrC, neo7); L-glutamine:DOI aminotransferase gene (btrS, neo6); a putative glycosyltransferase gene (btrM, neo8); a putative aminotransferase (similar to glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase) gene (btrB, neo18); a putative alcohol dehydrogenase gene (btrE, neo5); and another putative dehydrogenase (similar to chorine dehydrogenase and related flavoproteins) gene (btrQ, neo11).[17] A deacetylase acting to remove the acetyl group on N-acetylglucosamine moieties of aminoglycoside intermediates (Neo16) remains to be clarified (sequence similar to BtrD).[18]

Next is the attachment of the D-ribose via ribosylation of neamine, using 5-phosphoribosyl-1-diphosphate (PRPP) as the ribosyl donor (BtrL, BtrP);[19] glycosyltransferase (potential homologues RibF, LivF, Parf) gene (Neo15).[20]

Neosamine B (L-neosamine B) is most likely biosynthesized in the same manner as the neosamine C (D-niosamine) in neamine biosynthesis, but with an additional epimerization step required to account for the presence of the epimeric neosamine B in neomycin B.[21]

Neomycin C can undergo enzymatic synthesis from ribostamycin.[22]

Composition

Standard grade neomycin is composed of several related compounds including neomycin A (neamine), neomycin B (framycetin), neomycin C, and a few minor compounds found in much lower quantities. Neomycin B is the most active component in neomycin followed by neomycin C and neomycin A. Neomycin A is an inactive degradation product of the C and B isomers.[23] The quantities of these components in neomycin vary from lot-to-lot depending on the manufacturer and manufacturing process.[24]

DNA binding

Aminoglycosides such as neomycin are known for their ability to bind to duplex RNA with high affinity.[25] The association constant for neomycin with A-site RNA is in the 109 M−1 range.[26] However, more than 50 years after its discovery, its DNA-binding properties were still unknown. Neomycin has been shown to induce thermal stabilization of triplex DNA, while having little or almost no effect on the B-DNA duplex stabilization.[27] Neomycin was also shown to bind to structures that adopt an A-form structure, triplex DNA being one of them. Neomycin also includes DNA:RNA hybrid triplex formation.[28]

References

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 507. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- US 2799620, Waksman SA, Lechevalier HA, "Neomycin and process of preparation", issued 18 July 1957, assigned to Rutgers Research and Educational Foundation.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1952". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- "Neomycin". Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia. Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). 2007. pp. 2415–2416.

- Waksman SA, Lechevalier HA (March 1949). "Neomycin, a New Antibiotic Active against Streptomycin-Resistant Bacteria, including Tuberculosis Organisms". Science. New York, N.Y. 109 (2830): 305–7. Bibcode:1949Sci...109..305W. doi:10.1126/science.109.2830.305. PMID 17782716.

- Heidary N, Cohen DE (September 2005). "Hypersensitivity reactions to vaccine components". Dermatitis. 16 (3): 115–20. doi:10.1097/01206501-200509000-00004. PMID 16242081. S2CID 31248441.

- DermNet dermatitis/neomycin-allergy

- "Your Medicine Cabinet". DERMAdoctor.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-07-09. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- "Neomycin sulfate, EP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). TOKU-E. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Zug KA, Warshaw EM, Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Belsito DL, Pratt MD, et al. (2009). "Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005-2006". Dermatitis. 20 (3): 149–60. doi:10.2310/6620.2009.08097. PMID 19470301. S2CID 24088485.

- Lee C, de Silva AJ (March 1979). "Interaction of neuromuscular blocking effects of neomycin and polymyxin B". Anesthesiology. 50 (3): 218–20. doi:10.1097/00000542-197903000-00010. PMID 219730. S2CID 13551808.

- Mehta R, Champney WS (September 2003). "Neomycin and paromomycin inhibit 30S ribosomal subunit assembly in Staphylococcus aureus". Current Microbiology. 47 (3): 237–43. doi:10.1007/s00284-002-3945-9. PMID 14570276. S2CID 23170091.

- Gabev E, Kasianowicz J, Abbott T, McLaughlin S (February 1989). "Binding of neomycin to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 979 (1): 105–12. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(89)90529-4. PMID 2537103.

- "G418/neomycin-cross resistance?". Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Waksman SA, Lechevalier HA, Harris DA (September 1949). "Neomycin—Production and Antibiotic Properties 123". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 28 (5 Pt 1): 934–9. doi:10.1172/JCI102182. PMC 438928. PMID 16695766.

- Dewick M (March 2009). Medicinal natural products: a biosynthetic approach (3rd ed.). The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. pp. 508, 510, 511. ISBN 978-0-470-74168-9.

- Kudo F, Yamamoto Y, Yokoyama K, Eguchi T, Kakinuma K (December 2005). "Biosynthesis of 2-deoxystreptamine by three crucial enzymes in Streptomyces fradiae NBRC 12773". The Journal of Antibiotics. 58 (12): 766–74. doi:10.1038/ja.2005.104. PMID 16506694.

- Park JW, Park SR, Nepal KK, Han AR, Ban YH, Yoo YJ, et al. (October 2011). "Discovery of parallel pathways of kanamycin biosynthesis allows antibiotic manipulation". Nature Chemical Biology. 7 (11): 843–52. doi:10.1038/nchembio.671. PMID 21983602.

- Kudo F, Fujii T, Kinoshita S, Eguchi T (July 2007). "Unique O-ribosylation in the biosynthesis of butirosin". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 15 (13): 4360–8. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.040. PMID 17482823.

- Fan Q, Huang F, Leadlay PF, Spencer JB (September 2008). "The neomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces fradiae NCIMB 8233: genetic and biochemical evidence for the roles of two glycosyltransferases and a deacetylase". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 6 (18): 3306–14. doi:10.1039/B808734B. PMID 18802637. S2CID 29942953.

- Llewellyn NM, Spencer JB (December 2006). "Biosynthesis of 2-deoxystreptamine-containing aminoglycoside antibiotics". Natural Product Reports. 23 (6): 864–74. doi:10.1039/B604709M. PMID 17119636.

- Kudo F, Kawashima T, Yokoyama K, Eguchi T (November 2009). "Enzymatic preparation of neomycin C from ribostamycin". The Journal of Antibiotics. 62 (11): 643–6. doi:10.1038/ja.2009.88. PMID 19713992.

- Cammack R, Attwood TK, Campbell PN, Parish JH, Smith AD, Stirling JL, Vella F (2006). "neomycin". Oxford Dictionary of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 453.

- Tsuji K, Robertson JH, Baas R, McInnis DJ (September 1969). "Comparative study of responses to neomycins B and C by microbiological and gas-liquid chromatographic assay methods". Applied Microbiology. 18 (3): 396–8. doi:10.1128/AEM.18.3.396-398.1969. PMC 377991. PMID 4907002.

- Jin Y, Watkins D, Degtyareva NN, Green KD, Spano MN, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Arya DP (January 2016). "Arginine-linked neomycin B dimers: synthesis, rRNA binding, and resistance enzyme activity". MedChemComm. 7 (1): 164–169. doi:10.1039/C5MD00427F. PMC 4722958. PMID 26811742.

- Kaul M, Pilch DS (June 2002). "Thermodynamics of aminoglycoside-rRNA recognition: the binding of neomycin-class aminoglycosides to the A site of 16S rRNA". Biochemistry. 41 (24): 7695–706. doi:10.1021/bi020130f. PMID 12056901.

- Arya DP, Coffee RL (September 2000). "DNA triple helix stabilization by aminoglycoside antibiotics". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 10 (17): 1897–9. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00372-3. PMID 10987412.

- Arya DP, Coffee RL, Charles I (November 2001). "Neomycin-induced hybrid triplex formation". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 123 (44): 11093–4. doi:10.1021/ja016481j. PMID 11686727.