Fungi in art

Fungi are a common theme or working material in art. They appear in many different artworks around the world, starting as early as around 8000 BCE.[1] Fungi appear in nearly all art forms, including literature, paintings, and graphic arts; and more recently, contemporary art, music, photography, comic books, sculptures, video games, dance, cuisine, architecture, fashion, and design. There are a few exhibitions dedicated to fungi, and even an entire museum (the Museo del Hongo in Chile).

- Pre-Columbian mushroom sculptures (c. 1000 BCE – c. 500 CE)

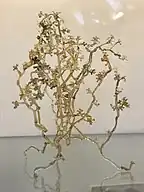

- A glass sculpture (c. 1940) by mycologist William Dillon Weston, depicting the Botrytis cinerea, a phytopathogen

- 'Champi(gn)ons' (2017), a sculpture by artist Vera Meyer made with parasol mushrooms (Macrolepiota procera, metal, shellac, 30 x 20 x 8 cm).

- 'MY-CO SPACE' (2018), a building prototype using the mycelium of Fomes fomentarius.

Contemporary artists experimenting with fungi often work within the realm of BioArts and may use fungi as materials. Artists may use fungi as allegory, narrative, or props; they may also film fungi with time-lapse photography to display fungal life cycles or try more experimental techniques. Artists using fungi may explore themes of transformation, decay, renewal, sustainability, or cycles of matter. They may also work with mycologists, ecologists, designers, or architects in a multidisciplinary way.

Artists may be indirectly influenced by fungi via derived substances (such as alcohol or psilocybin). They may depict the effects of these substances, make art under the influence of these substances, or in some cases, both.

By artistic area

In Western art, fungi have been historically saturated with negative associations, whereas Asian art and folk art are generally more favourable towards fungi. Reflecting these representations of mushrooms, Western cultures have been referred to as mycophobes (fear, loathing, or hostility towards mushrooms), a term first coined as fungophobia by British mycologist William Delisle Hay in his 1887 book An Elementary Text-Book of British Fungi,[2][3] whereas Asian cultures have been generally described as mycophiles.[4][5]

Since 2020, the annual Fungi Film Festival has recognized movies about fungi in all genres.[6]

In some stories or artworks, fungi play an allegorical role, or part of mythology and folklore. The visible parts of some fungi – particularly mushrooms with a distinctive appearance (e.g., fly agaric) – have significantly contributed to folklore.[7]

Mushrooms

Early examples of mushrooms in art include:

- Drawings of masked shamans with mushrooms sprouting from their heads (c. 9500 BCE – c. 7000 BCE), in Algeria[1]

- Mushroom stones (c. 1500 BCE), in Guatemala[8]

- Petroglyphs of people (c. 0 CE) with mushroom-shaped heads from the Bronze Age, near the Pegtymel River in Siberia.[9]

Contemporary artists are more interested in fungi than ever before.[10]

Given the mysterious, seasonal, sudden, and at times inexplicable appearance of mushrooms, as well as the hallucinogenic or toxic effects of some species, their depiction in ethnic, classic and modern art (around 1860–1970) is often associated in Western art with the macabre, ambiguous, dangerous, mystic, obscene, disgusting, alien, or curious in paintings, illustrations, and works of fiction and literature.[11] British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote in his novel Sir Nigel:

- "The fields were spotted with monstrous fungi of a size and color never matched before—scarlet and mauve and liver and black. It was as though the sick earth had burst into foul pustules; mildew and lichen mottled the walls, and with that filthy crop Death sprang also from the water-soaked earth."[7]

In Asian or folk art, mushrooms are generally depicted in a more positive or mystical way than in Western art.[4][12][13]

Graphic arts

Visual artists representing mushrooms have been very prolific throughout history. The Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art, from the North American Mycological Association, curates an extensive virtual collection of mushrooms in the visual arts.[14] According to the registry, whereas examples before the 15th century are rare, examples abound from European visual arts from 1500 onwards including periods such as the Renaissance, the Baroque, Flemish, and Romantic periods.[14]

The shaggy ink cap (Coprinus comatus) and the common ink cap (Coprinus atramentaria) mushrooms produce black ink which is used in drawing, illustration, and calligraphy.[15][16]

Prehistoric art

Mushrooms have been found in art traditions around the world, including in western and non-western works.[17] Ranging throughout those cultures, works of art that depict mushrooms can be found in ancient and contemporary times. Often, symbolic associations can also be given to the mushrooms depicted in the works of art. For instance, in Mayan culture, mushroom stones have been found that depict faces in a dreamlike or trance-like expression,[18] which could signify the importance of mushrooms giving hallucinations or trances. Another example of mushrooms in Mayan culture deals with their codices, some of which might have depicted hallucinogenic mushrooms.[19] Other examples of mushroom usage in art from various cultures include the Pegtymel petroglyphs of Russia and Japanese Netsuke figurines.[17]

Paintings, tapestries, and illustrations

Artists, painters, illustrators, naturalists and scientists have depicted mushrooms in their artworks for millennia. Edible species like Caesar's mushroom (Amanita caesarea) and the King bolete (Boletus edulis) are more commonly depicted than toxic ones. Mushrooms abound in Italian, Flemish, Germanic, and Dutch Baroque landscapes and still lifes. Landscape paintings involving mushrooms occasionally depict mushroom or truffle hunting.[14]

Whereas historical British artworks tend to be considered to be influenced by a 'mycophobe' attitude, 19th-century Victorian fairy paintings depicting imaginary scenes involving fairies and other fantastic creatures often featured mushrooms. A great number of Victorian-era illustrators and children-book authors depicted mushrooms in their artworks, including Beatrix Potter, Hilda Boswell, Molly Brett, Arthur Rackham, Charles Robinson, and Cicely Mary Barker.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Visual artists who depicted mushrooms include:

- Lewis David von Schweinitz (1780–1834): illustrations of over 1000 fungal species which along with his contribution to mycology earned him the title of "Father of North American Mycology".[20][21]

- Charles Tulasne (1816–1884)

- Mary Elizabeth Banning (1822–1903): Mary Banning is best known as the author of The Fungi of Maryland, an unpublished manuscript containing scientific descriptions, mycological anecdotes, and 174 13" by 15" watercolor paintings of fungal species.[22] The New York State Museum describes these paintings as "extraordinary...a blend of science and folk art, scientifically accurate and lovely to look at."[23]

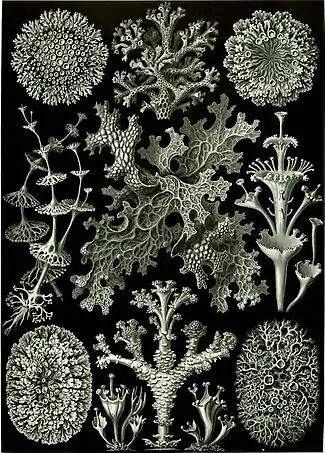

- Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919)

- Violetta White Delafield (1875-1949): creations of around 600 illustrations of fungi.[24][25] Delafield created hundreds of annotated watercolors of fungi and plants, noted for their level of detail; she made a note of the collection location, a detailed specimen description and analysed the cellular structure of the fungus with the help of a microscope.[26] Her extensive illustrations are particularly significant as fungal specimens tend to deteriorate soon after collection and would often change their colour and form. Delafield's significant collection of specimen was left to the Fungal Herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden, her papers and research materials on mycology and horticulture are held with the Delafield family papers by the University of Princeton.[27] A selection of her work was exhibited in 2019 at Bard College as part of the ‘Fruiting Bodies’ exhibition and has been preserved in a digital collection.[28]

- Alexander Viazmensky

Photography

Amateur and professional photographs of mushrooms abound on the Internet. Non-fiction books about fungi, especially those involving the identification of fungi, often include photographs of fungal species and their fruiting bodies. The book by Scott Chimileski and Roberto Kolter Life at the Edge of Sight: A Photographic Exploration of the Microbial World showcases 'the invisible world waiting in plain sight,' including fungi.[29] Since 2005, the North American Mycological Association (NAMA) organises an annual Photography Art Contest on mushrooms and fungi.[30][31]

In fiction

Works of literary fiction involving mushrooms and fungi are often linked to infection, decay, toxicity, mystery, fantasy, and ambiguity, and thus have mostly a negative connotation.[11] Examples of mushrooms depicted or involved in a positive way include:

- the children's book The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet (1954) by Eleanor Cameron[32]

- the science-fiction novel Omnivore (1968) by Piers Anthony (part of the Of Man and Manta trilogy)[33]

- The Way Through the Woods: On Mushrooms and Mourning (2019) by Long Litt Woon.[34]

In line with the assumption by Robert Gordon Wasson and Valentina Pavlovna Wasson that Russian society traditionally has more affinity to mushrooms,[5] a scene of mushroom foraging in Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina is associated with love, family, and a sense of commonality.[5][11] During the Victorian era, fungi started to acquire a more playful, childish, or jolly role in works of literary fiction.[11] The author, artist, illustrator, and mycologist Beatrix Potter created meticulous and accurate illustrations of mushrooms, including in her children-book series of Peter Rabbit.[11]

Authors who have used fungi as a plot device include:[35]

Fungi are a common trope in science fiction, horror, supernatural, fantasy and crime fiction. In Ray Bradbury's "Come into My Cellar", mushrooms are alien invaders threatening society. The short story is one of the rare examples in which several forms of fungi appear (spores and mushrooms): In the story, an alien form of spores from fungi lands on Earth and compels humans, and kids in particular, to grow mushrooms and infect more persons, thus using humans as a medium of propagation of fungi through mind control.[36] Fungi have occasionally appeared in the murder mystery literature due to their toxicity. Crime and detective writer Agatha Christie has used mushrooms as murder weapons in her crime fiction.[11]

The use of (toxic) mushrooms in fiction does not often reflect reality, either because a misidentified species is used (for example, a non-toxic one), because the preparation or intake of the toxic is wrong (for example, when not enough toxin is present, or when it should be deactivated by cooking), or because the progress of poisoning is unrealistic (for example, if the toxin kills too quickly).[7][37]

The "Bad Bug Bookclub" at Manchester Metropolitan University is a regular book club run by Joanna Verran that discusses literary works on microorganisms, including fungi.[38] The quarterly periodical FUNGI Magazine runs a column called Bookshelf Fungi reviewing fiction and non-fiction books on fungi.

In poetry

In Western culture poetry, as in literature, fungi are often associated with negative feelings or sentiments. The poem The Mushroom (1896) by Emily Dickinson is unsympathetic towards mushrooms. American author of weird horror and supernatural fiction H. P. Lovecraft created a collection of cosmic horror sonnets with fungi as subjects called Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30). Margaret Atwood's poem Mushrooms (1981) explores the topics of the life cycle and nature. The poem by Neil Gaiman, The Mushroom Hunters, is a poem touching, through the lens of mushroom hunting throughout history, on the topics of womanhood, human creation, and destruction. The poem was written for 'Universe in Verse,' a festival combining science with poetry, and won the Rhysling Award for best long poem in 2017. The poem features in a short animated video with the voice-over of Amanda Palmer.[39]

Several hundred Japanese haiku are about mushroom hunting. Many of them were written by poets of the Nara, Edo and Meiji periods,[40] such as:

- Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694)

- Kitamura Koshun (1650–1697)

- Mukai Kyorai (1651–1704)

- Naitō Jōsō (1662–1704)

- Hattori Ransetsu (1654–1707)

- Takarai Kikaku (1661–1707)

- Hirose Izen (1688?–1711)

- Morikawa Kyoriku (1656–1715)

- Yamaguchi Sodō (1642–1716)

- Kagami Shikō (1665–1731)

- Kumotsu Suikoku (1682–1734)

- Kuroyanagi Shōha (1727–1772)

Storytelling, oral tradition, myth, and folklore

Through storytelling and oral tradition, fungi have influenced mythology, folklore, and religions across civilizations and historical periods.[7] The psychoactive properties of certain fungi have contributed to the involvement of fungi in myth and folklore.[41] In her essay Jesus if a Fungal God, author Sophie Strand writes:

- "As we learn more about fungi, let us embrace that they have always been here. Beneath our feet. And inside our most popular myths.".[42]

There are numerous deities associated with wine and beer, which is an indirect effect of fungi in the arts. Fungi play a role in several religions, for example through fermentation (e.g. wine) and leavening (e.g. bread). In the Parable of the Leaven, one of the Parables of Jesus, the growth of the Kingdom of God is akin to the leavening of bread through yeast. According to Matthew 13:33 (and, similarly, to Luke 13:20-21):

- "He told them still another parable: 'The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed into about sixty pounds of flour until it worked all through the dough.'"[43]

However, yeast is associated with corruption in other passages of the New Testament, as in Luke 12:1:

- "Jesus began to speak first to his disciples, saying: 'Be on your guard against the yeast of the Pharisees, which is hypocrisy.'"[44]

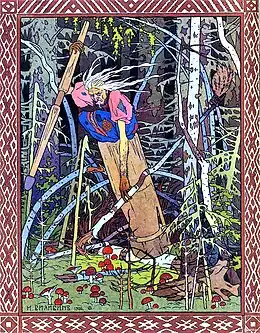

Some scholars argue that the Egyptian God of the afterlife Osiris is a personification of entheogenic mushrooms. As evidence, they indicate that Egyptian crowns are shaped like primordia of Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms. The Egyptian tale known as Cheops and the Magicians illustrates the growth of mushrooms on barley.[45] In the Chinese classic tale The Mountain and the Sea, the soul of a young woman becomes a mushroom as a symbol of immortality. In Lithuanian and Baltic mythology, fungi are considered the fingers of Velnias, the God of the underworld, reaching up from the underground to feed the poor.[7] In Slovenia, there is a folk ritual to roll on the ground during thunder as a way to increase the amount of mushrooms harvested.[46] Baltic and Ugric religions include mushroom elements, including a "Mother of Mushrooms". The popular tale The War of the Mushrooms is told in several Slavic cultures. (After the start of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, an exhibition at the Ukrainian Museum in New York revisited the classic story in light of current events.[47]) The supernatural being Baba Yaga in Slavic folklore is often associated with mushrooms. In some Russian tales, it often appears as a villainous wizard called Mukhomor, literally 'poison mushroom,' which is assumed to be derived from the fly agaric.[12][48]

The fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) is a mushroom with characteristic red cap and white dots and has greatly infiltrated folklore with mainstream popularity.

According to several interpretations, the legendary figure of Santa Claus may have been influenced by the fly agaric; evidence includes the use by Saami shamans in the Lapland region, who would visit the homes of people by reindeer-drawn sleds and enter through the chimney when the entrance door was stuck by snowfalls; the fondness of reindeers in eating fly agaric mushrooms; the belief by Saami people that whoever eats an Amanita muscaria will resemble it, becoming among other things, plump and reddish; and the sense of flying that consumption of fly agaric might induce.[49]

The stinkhorn Phallus indusiatus (or "veiled lady") has entered folklore across many cultures, probably due to its peculiar shape. In French, P. indusiatus is commonly called le satyre voilé ('the veiled satyr,' from the male nature spirit in Greek mythology). According to ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson, P. indusiatus was consumed in Mexican divinatory ceremonies on account of its suggestive shape. On the other side of the globe, New Guinea natives consider the mushroom sacred.[50] In Nigeria, the mushroom is one of several stinkhorns given the name Akufodewa by the Yoruba people. The name is derived from a combination of the Yoruba words ku ("die"), fun ("for"), ode ("hunter"), and wa ("search"), and refers to how the mushroom's stench can attract hunters who mistake its odour for that of a dead animal.[51] The Yoruba have been reported to have used it as a component of a charm to make hunters less visible in times of danger. In other parts of Nigeria, they have been used in the preparation of harmful charms by ethnic groups such as the Urhobo and the Ibibio people. The Igbo people of east-central Nigeria called stinkhorns éró ḿma, from the Igbo words for "mushroom" and "beauty".[52]

Jews have a long tradition of eating mushrooms, which are considered Kosher in Jewish dietary law, and mushrooms have been referred to as "Jew's Meat" at least in parts of current Germany (Rhineland area), where the term is used as a dialect term for the German "Pilz" according to the Rheinisches Wörterbuch.[53] Mushrooms have been used as an instrument for anti-Semitic discrimination or propaganda over the centuries. This has a disparaging connotation, especially during the Middle Ages, when mushrooms were considered toxic and disgusting. In the infamous 1938 children-book Der Giftpilz (transl. The poisonous mushroom) from Nazi Germany, Jews are depicted as poisonous and difficult to distinguish from 'Gentiles'.[54]

Non-fiction books

There is a large corpus of literature on mushrooms, including foraging, identifying, growing, and cultivating fungi. The book The Mushroom at the End of the World by Chinese-American anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing on matsutake mushrooms offers insights into the cultural relevance and the significance of fungi for modern society, circularity, and decay.[55] Authors of non-fictional books about fungi contribute to the increased popularity and development of mycology, fungal ecology, mycoremediation, fungal conservation, biocontrol, medicinal fungi, mushroom gathering and identification, and fungal research.[56][57][58][59]

Cinema, TV shows, and motion pictures

Adaptations of literary fiction about fungi into motion pictures include the 2016 British post-apocalyptic science fiction horror movie The Girl with All the Gifts, based on the novel with the same title; and the 1963 Japanese horror film Matango (マタンゴ) directed by Ishirō Honda, partially based on William Hope Hodgson's short story The Voice in the Night (1907). The documentary Fantastic Fungi (2019), primarily led by mycologist Paul Stamets, presents the world of fungi using time-lapse photography.[60] The documentary The Mushroom Speaks (2001) by Marion Neumann covers topics such as decay, bioremediation, and symbiosis by following scientists, experts, and fungal pioneers.[61]

Film festivals dedicated to fungi include the Fungi Film Festival (since 2021), by Radical Mycology author Peter McCoy;[62] and the UK Fungus Day Film Festival (since 2022), by the British Mycological Society.[63]

Performing arts

The American stand-up comedian and satirist Bill Hicks drew inspiration from Terence McKenna's 'Stoned Ape Theory' (that psilocybin was crucial in the development of human nature[64]) in his 1993 show Revelation.[7][65]

Comic books and video games

In The Smurfs, smurfs inhabit houses resembling mushrooms. American fantasy and science fiction comic book artist Frank Frazetta illustrated the cover image of the 1964 edition of the novel The Secret People (1935) by John Beynon (pseudonym of John Wyndham), in which fictive 'little people' inhabit areas with giant mushrooms. In Nintendo's Super Mario video game, the 'super mushroom' helps the character grow in size.[11] The video game franchise The Last of Us is set in a post-apocalyptic United States, after spores of a mutant fungus wiped out humanity, turning infected people into zombies. Other video games where mushrooms appear include Skyrim (2011), Stardew Valley (2016), and Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017).[66]

Music

Mushrooms have an influence on music as a subject, cultural reference, or medium for music creation. Numerous musicians, bands, composers, and lyricists mentioned or drew inspiration from fungi. Music can be created utilizing fungi, as in the process of bio-sonification. American composer John Cage (1912–1992) was an enthusiastic amateur mycologist and co-founder of the New York Mycological Society who often merged his two passions in his artworks.[67]

Music inspired by

Numerous musicians, bands, composers, and lyricists mentioned or drew inspiration from fungi, like the Israeli psychedelic trance band Infected Mushroom, the US heavy metal band Mushroomhead, Russian romantic composer Modest Mussorgsky's (1839-1881) song Gathering Mushrooms, Igor Stravinsky's (1882-1971) How the Mushrooms went to War, and many more.[7] In Women Gathering Mushrooms, the musicologist Louis Sarno (1954-2017) recorded women from the Central Africa Mbenga pygmy tribe of the Aka (also Biaka, Bayaka, Babenzele) sideclinging while collecting mushrooms, resulting in a polyphonic composition. According to mycologist and author Merlin Sheldrake, the activity of the gatherers above ground mirrors the fungal life below ground, as "mycelium is polyphony in bodily form".[68] Icelandic avant-garde musician Björk's 2022 album Fossora (including tracks such as Mycelia, Sorrowful Soil, and Fungal City) is referred to as her "mushroom album".[69] 'Fossora' can be translated from Latin into "she who digs".[70][71] The rap artist 'FungiFlows' composes lyrics inspired by fungi and mushrooms while wearing a fly-agaric-shaped hat.[72] The Czech composer and mycologist Václav Hálek (1937–2014) is said to have composed over 1,500 symphonies inspired by fungi, including the composition called Mycosymphony.[7][73]

A non-exhaustive list of songs inspired by mushrooms (fungi) is given below:

- Mushroom Cantata by Lepo Sumera

- Mycosymphony by Václav Hálek

- Solar Waltz (2018) by Cosmo Sheldrake

- Fungus (2021) by The Narcissist Cookbook

- Mycelia (2022) by Björk

- Fungal City (2022) by Björk

Music created with

Fungi are occasionally a direct medium for the creation of music. With the use of sonification and synthezisers, musicians and bioartists are able to create sounds and music by converting mushrooms' bioelectric signals.[74][75][76] The 'Nanotopia Midnight Mushroom Music' is a radio station devoted to streaming mushroom-generated music. Some artists creating music by sonicating mushrooms note that different mushrooms produce different sounds: for example, Ganoderma lucidum produces melodic sounds, while Pleurotus ostreatus produces constant sounds.[77]

Architecture and sculptures

In architecture and sculpture, mushrooms are mostly represented or showcased. Mushrooms are carved in buildings or depicted in sculptures or potteries, like pre-Columbian pottery mushrooms from Mesoamerica.[78][79] At the entrance of Park Güell by Catalan modernist architect Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), the Porter's Lodge pavilion features a lookout tower with a mushroom-shaped dome, probably inspired by Amanita muscaria or by stinkhorns.[80][81] The sculpture Triple Mycomorph by Bernard Reynolds (1915–1997) at Christchurch Mansion holds a resemblance with the stinkhorn mushroom Phallus indusiatus.[82] Mushrooms are occasionally showcased by artists who collect, manipulate, preserve, and exhibit them, as in the 'Mind The Fungi' exhibition (2019-2020) at Futurium in Berlin (Germany).[83][84][85]

The mycologist William Dillon Weston (1899-1953; sometimes also spelled Dillon-Weston[86]) created glass sculptures of microfungi, mostly plant pathogens, to fight bouts of insomnia. The artworks represent either magnified fungi (usually up to 400X times for fungi; up to 1200X for spores) or real-size plants affected by fungi (like in Ustilago maydis and Phytophthora infestans) and are made mostly of transparent or opaque glass. The sculptures are mostly between 5–20 cm in size and often do not have a base and stand on the mycelium.[87] Almost a hundred glass sculptures are conserved at the Whipple Museum in Cambridge (UK). Fungi represented are among others species from the genera Alternaria, Botrytis, Penicillium, Cordyceps, Sclerotinia, Fusarium, Puccinia as well as spores (ascospores, basidiospores).[88][89] The other known example of glass sculptures representing (among others) fungi is the Blaschka Glass Flowers at Harvard Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts (US).[88]

Culinary arts

Fungi enter cuisine mostly as fruiting bodies (mushrooms), yeasts, or moulds. Mushrooms are a source of protein, a staple in many cultures and cuisines, and a common ingredient in many recipes worldwide. The North American Mycological Association (NAMA) hosts a series of resources to encourage all aspects of 'mycophagy.' Most mushrooms sold commercially are the button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus), commonly known as champignons. Many mushrooms, including some coveted in haute cuisine, like truffles and boletus, cannot be cultivated and need to be harvested. Due to their dietary properties and their suitability as a meat substitute, mushrooms can be considered a novel trend, including the cultivation and consumption of species that only recently became popular in cooking, like Cordyceps.[90][91][92] Many fungi are considered delicacies in cuisine and gastronomy. Truffles, which are occasionally confused with tubers (storage organs in plants, like potatoes), are subterranean fruiting bodies (that is, mushrooms that grow below ground) of certain fungi belonging to the genera Tuber, Geopora, Peziza, Choiromyces, and others. Truffles have developed a distinctive aroma as a spore-dispersion strategy: Instead of relying on wind and other mechanical means, truffles attract animals that eat them and carry their spores to new locations after defecation.[15] Both the mushroom and the black ink of C. comatus and Coprinopsis atramentaria (the 'Common ink cap') are edible, but adverse effects might be felt if consumed together with alcohol. For this reason, C. atramentaria is also called "tippler's bane".[7]

Contemporary arts

Contemporary artworks involving fungi usually handle or utilize mycelia, yeasts, and other fungal forms rather than mushrooms. Fungi are occasionally used conceptually (that is, to communicate their capabilities and potential).[93] The video and light artist Philipp Frank creates so-called 'projection mapping' by casting light effects on mushrooms growing in nature in the 'Funky Funghy' project.[94][95]

Social games (board games, card games)

Plant pathology scientist Lisa Vaillancourt at the University of Kentucky developed a 'Fungal Mating Game' based on standard card decks as an educational tool for students to better understand the process and concept of fungal mating using the mating of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast), Neurospora crassa, Ustilago maydis, and Schizophyllum commune as an example. The game can be played both collaboratively and competitively.[96][97]

Mycelia or hyphae

Mycelia and hyphae have seldom been represented, showcased, transformed, or utilized in the traditional arts due to their invisibility and the general overlook. Depictions of mycelia and hyphae in the graphic arts are very rare. The mycelium of certain fungi, like those of the polypore fungus Fomes fomentarius which is sometimes referred to as Amadou, has been reported throughout history as a biomaterial.[98] More recently, hyphae and mycelia have been used as working matter and transformed into contemporary artworks, or used as biomaterial for objects, textiles and constructions. Mycelium is investigated in cuisine as innovative food or as a source of meat alternatives like so-called 'mycoproteins.'[99] The filamentous, prolific, and fast growth of hyphae and mycelia (like moulds) in suitable conditions and growth media often makes these fungal forms good subjects of time-lapse photography. Indirectly, psychoactive substances present in certain fungi have inspired works of art, like in the triptych by Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, with curious and visionary imagery inspired, according to some interpretations,[100] by ergotism poisoning caused by the sclerotia (hardened mycelium) of the phytopathogenic fungus Claviceps purpurea.

Graphic arts

.jpg.webp)

The German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470–1528) depicted in The Temptation of St. Anthony (1512-1516) a sufferer from ergotism, also referred to as St. Anthony's Fire. Ergotism is caused by the ingestion of sclerotia (hardened mycelium) of Claviceps purpurea, a fungal endophyte infecting rye and other plants. Ergotism is caused by the consumption of rye and other food contaminated with the sclerotia of the fungus, as in flour. Bread from contaminated flour looks black due to the sclerotia. The mycelium contains the fungal alkaloid ergotamine, a potent neurotoxin that can cause convulsions, cramps, gangrene of the extremities, hallucinations, and further adverse and potentially lethal effects depending on dosage. Ergotamine is a precursor molecule in the synthesis of psychedelic drug LSD.[79]

Music

Examples of hypha and mycelium influence in music are scarce. In her mushroom-inspired album Fossora (2022), Icelandic avant-garde musician Björk included tracks such as Mycelia and Fungal City. Fungi might have a direct influence on musical instruments. The process of wood spalting is often used as an aesthetic element, e.g. in the manufacturing of guitar bodies. The luthier Rachel Rosenkrantz experiments with fungi (mycelium) to create 'Mycocast,' a guitar body made of fungal biomass due to the acoustic properties of mycelium and its growth plasticity (i.e. the ability to take virtually any shape upon being cast in a desired form).[101] According to an interpretation, violins from wood infiltrated by mycelia of the fungus Xylaria polymorpha (commonly called 'dead man's fingers') produce sounds close to those from a Stradivarius violin.[7] Researchers are investigating the use of fungi to the species Physisporinus vitreus and Xylaria longipes in controlled wood decay experiments to create wood with superior qualities for musical instruments.[102][103][104] In some cases, music generation using fungi is conceptual, as in Psychotropic house (2015) and Mycomorph lab (2016) of the Zooetic Pavillion by the Urbonas Studio based in Vilnus (Lithuania) and Cambridge (Massachusetts), in which a mycelial structure is designed to act as an amplifier for sounds from nature mixed into loops.[105][106]

Architecture, sculptures, and mycelium-based biomaterials

Direct applications of fungi in architecture (as well as design and fashion) often start with artistic experimentations with fungi.[83][107][108] Mycelium is being investigated and developed by researchers and companies into a sustainable packaging solution as an alternative to polystyrene.[109] Mycelium as a working matter in sculptures is attracting interest from artists working in the contemporary arts.[13]

Early experimentations by artists with mycelia have been exhibited at the New York Museum of Modern Art.[110] Experimentations with fungi as components– and not only as contaminants or degraders of buildings – started around 1950.[111] Collaborations between scientists, artists, and society at large are investigating and developing mycelium-based structures as building materials.[112] Use of fungi from the genera Ganoderma, Fomes, Trametes, Pycnoporus, or Perenniporia (and more) in architecture include applications such as concrete replacement, 3D printing, soundproof elements, insulation, biofiltration, and self-sustaining, self-repairing structures.[113][114][115][116]

Besides the study of fungi for their beneficial application in architecture, risk assessments investigate the potential risk fungi can pose with regard to human and environmental health, including pathogenicity, mycotoxin production, insect attraction through volatile compounds, or invasiveness.[117]

Fashion, design, and mycelium-based textiles

_Current_state_and_future_prospects_of_pure_mycelium_materials.jpg.webp)

Historically, ritual masks made of lingzhi mushroom (species from the genera Ganoderma) have been reported in Nepal and indigenous cultures in British Columbia.[12] Fungal mycelia are molded, or rather grown, into sculptures and bio-based materials for product design, including into everyday objects, to raise awareness about circular economics and the impact that petrol-based plastics have on the environment.[119][120] Biotechnology companies like Ecovative Design, MycoWorks, and others are developing mycelium-based materials that can be used in the textile industry. Fashion brands like Adidas, Stella McCartney, and Hermès are introducing vegan alternatives to leather made from mycelium.[121][122][123][124][125][118]

The tinder polypore Fomes fomentarius (materials derived from which are referred to as 'Amadou') has been used by ancestral cultures and civilizations due to its flammable, fibrous, and insect-repellent properties.[7] Amadou was a precious resource to ancient people, allowing them to start a fire by catching sparks from flint struck against iron pyrites. Bits of fungus preserved in peat have been discovered at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr in the UK, modified presumably for this purpose. [126] Remarkable evidence for its utility is provided by the discovery of the 5,000-year-old remains of "Ötzi the Iceman", who carried it on a cross-alpine excursion before his death and subsequent ice-entombment.[127] Amadou has great water-absorbing abilities. It is used in fly fishing for drying out dry flies that have become wet.[128][129] Another use is for forming a felt-like fabric used in the making of hats and other items.[130][131] It can be used as a kind of artificial leather.[132] Mycologist Paul Stamets famously wears a hat made of amadou.[133]

Fungi have been used a biomaterial since many centuries, for example as fungus-based textiles. An early example of such "mycotextiles" comes from the early 20th century: a wall pocket originating from the Tlingit, an Indigenous Population from the Pacific Northwest (US) and displayed as historical artefact at the Dartmouth College's Hood Museum of Art, turned out to be made of mycelium from the tree-decaying agarikon fungus.[134] Fungal mycelia are used as leather-like material (also known as pleather, artificial leather, or synthetic leather), including for high-end fashion design products.[135]

Beside their use in clothing, fungus-based biomaterials are used in packaging and construction.[136] There are several advantages and potentials of using fungus-based materials rather than commonly used ones. These includes the smaller environmental impact compared with the use of animal products; vertical farming, able to decrease land use; the thread-like growth of mycelium, able to be molded into desirable shapes; use of growth substrate derived from agricultural wastes and the recycling of mycelium within the principles of circular economy; and mycelium as self-repairing structures.[137][138][139]

Culinary arts

Mushrooms are traditionally the main form of fungi used for direct consumption in the culinary arts. The fermentative abilities of mould and yeasts have a direct influence on a great variety of food products, including products such as beer, wine, sake, kombucha, coffee, soy sauce, tofu, cheese, and chocolate.[140] Recently, mycelium has been increasingly investigated as an innovative food source. The restaurant The Alchemist in Copenhagen (Denmark) experiments with mycelium of fungi such as Aspergillus oryzae, Pletorus (oyster mushroom), and Brettanomyces with funding from the Good Food Institute, to create novel fungus-based dishes, including the creation of mycelium-based seafood and the consumption of raw, fresh mycelium grown on a Petri dish with a nutrient-rich broth.[141] The US-based company Ecovative is creating fungus-based food as a meat alternative, including mycelium-based bacon.[142][143] The US-based company Nature's Fynd is developing various kinds of food products, including meatless patties and cream cheese substitutes, using the so-called 'Fy' protein from Fusarium.[144]

Contemporary arts

"At this point, I stepped back and let the sculpture sculpt itself."

— Xiaojing Yan, Mythical Mushrooms: Hybrid Perspectives on Transcendental Matters

Hypha and mycelium get attention as working matter in contemporary art due to their growth and plasticity and are used to explore the biological properties of degradation, decomposition, budding ('mushrooming'), and sporulation. An early form of BioArt is Agar art, where various microorganisms (including fungi) are grown on agar plates into desired shapes and colours. Thus, the agar substrate becomes a canvas for microbes, which are an analogue to the artist's colour repertoire (palette). In agar art, fungi (and other microorganisms, mostly bacteria) assume different appearances based on intrinsic characteristics of the fungus (species, morphology, fungal form, pigmentation), as well as external parameters (like inoculation technique, incubation time or temperature, nutrient growth medium, etc.). Microorganisms can also be engineered to produce colours or effects which are not intrinsic to them or are not present in nature (e.g., they are mutant from the wild type), like for example bioluminescence. The American Society for Microbiology (ASM) holds an annual 'Agar Art Contest' which attracts considerable attention and elaborate agar artworks.[145][146] An early 'agar artist' was physician, bacteriologist and Nobel Prize winner Alexander Fleming (1881-1955).[147][148]

The Folk Stone Power Plant (2017), like the Mushroom Power Plant (2019), by Lithuanian artist duo Urbonas Studio, are physical installations based on 'mycoglomerates,' which is an interpretation and representations of vaguely-described microbial symbioses aimed at energy production alternative to fossil fuel.[13][149] The Folk Stone Power Plant is a 'semi-fictional' alternative battery installed in Folkestone (UK) during the Folkestone Triennale, aiming at a reflection about symbioses (both in nature and between artists and scientists) and about unconventional power sources. The design is based on drawings from polymath and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), while the microbial power source, hidden within the stone, mirrors the largely unnoticed, yet crucial, contribution of mycelial networks (that is, mycorrhiza) in ecology.[13]

In Chinese-Canadian artist Xiaojing Yan's work, Linghzi Girl (2020), female bust statues cast with the mycelium of lingzhi fungus (Ganoderma lingzhi) are exhibited and left to germinate. From the mycelium-based sculptures sprout mushrooms which eventually spread; once ripe, a cocoa-powder dust of spores blooms on the bust, after which the sculptures are preserved by desiccation to stop the fungal cycle and maintain the artwork.[151] Artist Xiaojing Yan thus explains the audience's reaction to her work:

- "The uncanny appearance of these busts seems frightening for many viewers. But a Chinese viewer would recognize the lingzhi and immediately become delighted by the discovery."[12]

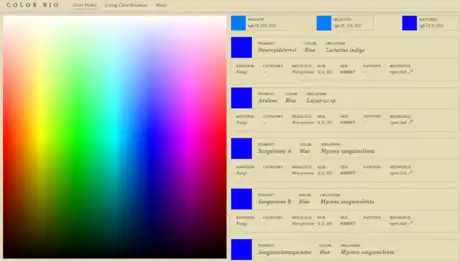

During an artist-in-residence project The colors of life (2021) at the Techische Universität Berlin (Germany), artist Sunanda Sharma focuses on the fungus Aspergillus niger, and visualises its black pigmentation through fungal melanin by means of video, photography, animation, and time-lapse footage. Within the same residence, the artist created an open-source database The Living Color Database (LCDB), which is an online compendium of biological colors for scientists, artists, and designers. The Living Color Database links organisms across the tree of life (in particular fungi, bacteria, and archaea) with their natural pigments, the molecules' chemistry, biosynthesis, and colour index data (HEX, RGB, and Pantone), and the corresponding scientific literature. The Living Color Database comprises 445 entries from 110 unique pigments and 380 microbial species.[150]

Spores

Fungal spores are the equivalent of seeds in plants; mushrooms are fungal structures where spores mature and are released from. Many fungi do not form spores but reproduce by budding like yeasts; other fungi form so-called 'vegetative spores,' which are specialized cells able to withstand unfavorable growth conditions, as in black yeasts. Lichens also do not reproduce and disperse by sporulation.[152]

Single fungal spores are invisible to the naked eye and examples of artworks involving spores are rarer than artworks involving other fungal forms. Fungal spores are employed as an agent of contamination, invasion, infection or decay in works of fiction (e.g. The Last of Us). In contemporary art, spores might be used to reflect on the process of transformation.[12]

Graphic arts

So-called 'spore prints' are created by pressing the underside of a mushroom to a flat surface, either white or coloured, to allow the spores to be imprinted on the sheet. Since some mushrooms can be recognized based on the colour of their spores, spore prints are a diagnostic tool as well as an illustrative technique.[7] Several artists used and modified the technique of spore printing for artistic purposes. Mycologist Sam Ristich exhibited several of his spore prints in an art gallery in Maine around 2005–2008.[7] The North American Mycological Association (NAMA) created a 'how-to guide' for people interested in creating their own spore prints.[153]

The artwork Auspicious Omen – Lingzhi Spore Painting by Chinese-Canadian artist Xiaojing Yan creates abstract compositions resembling traditional Chinese landscapes by fixing spores of the linghzi fungus with acrylic reagents.[151] The linghzi mycelial sculptures by Xiaojing Yan, including Linghzi Girl (2020) and Far From Where You Divined (2017) are allowed to germinate into mushrooms during exhibition, creating a dust of spores raining down on the female busts, children, deer, and rabbits. The artworks are then desiccated for preservation, stopping the fungal growth and the metamorphosis of the sculptures. Artworks as such, including growth of the fungus, an incontrollable transformation of the art object, and several forms in the fungal life cycle, are rare.[12]

Comic books and video games

The video game franchise The Last of Us is a post-apocalyptic, third-person action-adventure game set in North America in the near future after a mutant fungus decimates humanity. The 'fungal apocalypse' is inspired by the effect ant-pathogenic fungi like Ophiocordyceps unilateralis have on their insect prey. The infected zombie-like creatures develop cannibalism after inhaling spores and can transmit the fungal infection to other humans by biting. A television adaptation aired in January 2023. "Come into My Cellar" by Ray Bradbury has been adapted into a comic strip by Dave Gibbon and an adaptation into Italian appeared for the comic series Corto Maltese in 1992 with the name "Vieni nella mia cantina".[154]

Yeasts, moulds, or lichens

Many fungi do not reproduce and disperse by spores. Instead, they live as single cells and reproduce by budding or fission as in yeasts, or live in a symbiosis with an algal or cyanobacterial partner as in lichens. Despite being unicellular, yeasts can reproduce sexually by mating and can occasionally grow in a filamentous way.[155] Moulds do form spores ('asexual spores') but no mushrooms, and grow into filaments (hyphae and mycelia) which thrive in moist environments and spoil food. Moulds, like those which spoil food, are major natural producers of antibiotics, like penicillin.

Yeasts, moulds, and lichens did not enter into the arts very often and their direct influence in the arts remains modest. Indirectly, yeasts have influenced art, as alcohol fermentation has contributed to different cultures around the globe and across time; in La traviata (1853) by Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi, for example, one of the best-known opera melodies is 'Libiamo ne' lieti calici' (in English, translated into "Let's drink from the joyful cups"), which is one of numerous brindisi (toast) hymn. Other testimonies of the indirect effect of yeasts in the arts are the numerous deities and myths associated with wine and beer. Yeasts and moulds are often an agent of decay and contamination in the arts, whereas recently they are increasingly used in contemporary art in a positive or neutral way to reflect on processes of transformation, interaction, decay, circular economy, and sustainability.[83][107]

Examples of yeasts, moulds or lichens in the arts include:

- Ernst Haeckel illustrations of lichens in Kunstformen der Natur (1904)

- Chemical compounds from some lichens are used as dyeing substances[11] (this is also true for compounds derived from mushrooms[150][156])

- In the science fiction novel Trouble with Lichen (1960) by John Wyndham, a chemical extract from a lichen is able to slow down the aging process, with a profound influence on society

- In Stephen King's horror short story Gray Matter (1973), a recluse man living with his son drinks a 'foul beer' and slowly transforms into an inhuman blob-like abomination that craves warm beer and shuns light and transmutes into a fungus-like fictional creature

- The short movie Who's Who in Mycology (2016) by Marie Dvoráková,[157] involves "a young trombone player [...] trying to open an impossible bottle of wine [...] and some mold gets in his way"

- The novel Lichenwald (2019) by Ellen King Rice, author of 'Mushroom Thrillers'[158] is a crime story involving lichens, dementia, and manipulations[159]

- The Dutch textile artist Lizan Freijsen created the Fungal Wall for the microbe museum Micropia, together with TextielMuseum Tilburg, a wall-sized tapestry with tufting resembling mould growth[160][161][162]

- From Peel to Peel project (2018) by biodesigner Emma Sicher, using the metabolic properties of yeasts and bacteria to create cellulose from food waste as biodegradable packaging material[163]

- In so-called 'mould paintings,' surfaces of buildings or sculptures are intentionally overgrown with moulds to create visually appealing effects

- The contemporary artist Kathleen Ryan creates oversized, composite sculptures of rotting fruits, like in the Bad Fruit series (2020)[164][165]

- The short movie Wrought (2022) by Joel Penner and Anna Sigrithur is a series of time-lapses exploring rot, fermentation and decay displaying moulds, yeasts, mushrooms, and further decomposers[166]

Performative arts (theatre, comedy, dance, performance art)

The musical theatre show The Mould That Changed the World is a show running both in the US (in Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, Georgia) and the UK (in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Scotland) which centers around the life and legacy of Alexander Fleming, the Scottish discoverer of the antibiotic penicillin and 1945 Nobel Prize winner in Physiology or Medicine.[167][168] Alexander Fleming discovered in 1928 during his work as bacteriologist that bacteria growing on a Petri dish were inhibited by a mould contamination, namely from a fungus of the genus Penicillium, from which the antibiotic name 'penicillin' derives. The story involves jumps in time to highlight the legacy of the discovery of antibiotics and is partly set during the Great War, when Alexander Fleming served as a private, as well as the personification of some characters (e.g. Mother Earth). The musical has been developed for educational purposes to raise awareness against the tremendous, worldwide threat that the rise of antimicrobial resistance poses.[169][170] The musical provides teaching resources[167] and has been developed with the participation of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC).[168] The musical choir is composed of both professional singers and actors as well as health care professionals, lab technicians, and scientists, and is an example of an artistic project merging science and the arts.[167]

The dance contest for scientists called 'Dance your Ph.D.' sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an annual competition established in 2008 encouraging communication and education of complex scientific topics through interpretative dance. All scientific fields and areas of research are covered (biology, chemistry, physics, and social science), and several contestant entries involved fungi, including some winners. The 2014 winner was plant pathologist and aerial acrobat Uma Nagendra from the University of Georgia (Athens) with Plant-Soil Feedbacks After Severe Tornado Damage, a trapeze-circus dance representing the effect of extreme environmental events (like tornadoes) on tree seedlings and the positive effect those events can have with regard to withstanding phytopathogenic fungi.[171] The 2022 winner was Lithuanian scientist Povilas Šimonis from Vilnius University with Electroporation of Yeast Cells, a dance illustrating the effect of electroporation (a method involving pulses of electricity to deactivate cells, or make them more porous and prone to acquire extracellular DNA, a crucial step in genetic engineering) on yeasts.[172]

Contemporary arts

In the contemporary arts, works involving fungi are often interactive and/or performative and tend to transform and utilize fungi rather than merely represent and showcase them.[173] In her work, Myconnect (2013), bioartist Saša Spačal invites the audience to interact with the artwork, involving Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) or Oyster mushrooms (from the genus Pleurotus), which takes the form of a capsule connecting the human with the fungus on a sensory level.[173] Bioartists use yeasts to provoke a reflection on genetic engineering. Slovenian intermedia artist Maja Smrekar's created yoghurt using genetically-modified yeast with a gene from the artist herself in Maya Yoghurt (2012).[174] In 2015, the blogger and feminist Zoe Stavri baked sourdough bread using yeast she isolated from her own vaginal yeast infection using a Dildo, which she then mixed with flour and water and let leaven, and finally ate.[175][176][177] The activity, which she documented both on her blog posts and on social media, tagging it with the hashtag #cuntsourdough, caused a lot of discussion on social media, including repulsion, hate messages, and food safety concerns, as the practice did not involve axenic isolation of the leavening yeast; however, during baking, microorganisms present in the dough are most probably heat deactivated and thus harmless.[175] As the activist herself noted: "People have been making and eating sourdough [with wild yeasts] for millennia."[178] People had experimented before with microorganisms from the vaginal microbiota to create food and incite a reflection on the topic of food fermentation and female bodily autonomy and self-determination.

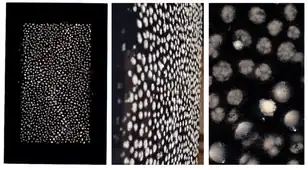

The exhibition Fermenting Futures (2022) by bioartists Alex May and Anna Dumitriu in collaboration with the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) is an artwork focusing on the role of yeast biotechnology confronting global issues of contemporary society. The artist cultured and showcased fermentation flasks of Pichia pastoris used for the bioconversion of carbon dioxide into biodegradable plastics. The artwork The Bioarchaeology of Yeast recreates by moulding the biodeterioration marks left by certain yeasts, like black yeasts, on work of art and sculptures, and displays them as aesthetic objects, reflecting on the process of erosion; the installation Culture used CRISPR technology to confer to a non-fermenting strain of Pichia pastoris the ability to ferment and work as a leavening agent as the baker's yeast.[180][181] A team of artists and researchers developed novel art techniques using the model (that is, widely studied in laboratory research) mould Aspergillus nidulans. The artist-scientist team described the development of two new techniques: 'Fungal Dot Painting' and 'Etched Fungal Art.' In Fungal Dot Painting, akin to pointillism where small dots unite to compose an image, fungal conidia are inoculated into agar droplets which are then deposited on a dark surface of black acrylic glass for contrast, and incubated at the desired condition to allow fungal growth. In 'Etched Fungal Art', an acrylic glass surface modified by etching (lathing or printmaking) is poured over with a suspension of fungal conidia in an agar-based substrate, and then incubated to permit fungal growth into the etched channels. Both art forms allow for temporal dynamism, insofar as being composed of living fungal organisms they change and evolve over time.[179]

See also

References

- Mastbaum, Blair (2 June 2022). "In Algeria, Ancient Cave Art May Show Psychedelic Mushroom Use". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 10 February 2023. (Retracted)

- Hay, William Delisle (1887). An Elementary Text-Book of British Fungi. London, S. Sonnenschein, Lowrey. pp. 6–7.

- Arora, David (1986). Mushrooms demystified: a comprehensive guide to the fleshy fungi (2nd ed.). Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-89815-170-8. OCLC 13702933.

- "Mycophile". The New Yorker. 11 May 1957. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Gordon Wasson, Robert; Pavlovna Wasson, Valentina (1957). Mushrooms, Russia, and History. New York: Pantheon Books.

- "Fungi Film Fest (FFF)". Fungi Film Fest. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- Millman, Lawrence (2019). Fungipedia: a brief compendium of mushroom lore. Amy Jean Porter. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-19538-4. OCLC 1103605862.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lowy, B. (1 September 1971). "New Records of Mushroom Stones from Guatemala". Mycologia. 63 (5): 983–993. doi:10.1080/00275514.1971.12019194. ISSN 0027-5514. PMID 5165831.

- Skarbo, Svetlana (14 September 2021). "Whale hunting and magic mushroom people of 2,000-year-old Eurasia's northernmost art gallery". The Siberian Times. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi". Somerset House. 9 May 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Lawrence, Sandra (2022). The magic of mushrooms: fungi in folklore, superstition and traditional medicine. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. London. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-78739-906-8. OCLC 1328029699.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yan, Xiaojing (20 October 2022). "Mythical Mushrooms: Hybrid Perspectives on Transcendental Matters". Leonardo. 56 (4): 367–373. doi:10.1162/leon_a_02319. ISSN 0024-094X. S2CID 253074757.

- Watlington, Emily (29 December 2021). "Mushrooms as Metaphors". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "ART REGISTRY - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Sheldrake, Merlin (May 2020). Entangled life: how fungi make our worlds, change our minds & shape our futures. New York. ISBN 978-0-525-51031-4. OCLC 1127137515.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Making Ink From Shaggy Ink Cap Mushrooms, retrieved 17 December 2022

- Yamin-Pasternak, Sveta (2011-07-07), "Ethnomycology: Fungi and Mushrooms in Cultural Entanglements", Ethnobiology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 213–230, doi:10.1002/9781118015872.ch13, ISBN 978-1-118-01587-2

- Lowy, B. (September 1971). "New Records of Mushroom Stones from Guatemala". Mycologia. 63 (5): 983–993. doi:10.2307/3757901. ISSN 0027-5514. JSTOR 3757901. PMID 5165831.

- Lowy, Bernard (July 1972). "Mushroom Symbolism in Maya Codices". Mycologia. 64 (4): 816–821. doi:10.2307/3757936. ISSN 0027-5514. JSTOR 3757936.

- Lynch, Dana M. (1996). "Paintings of Fungi by Lewis David von Schweinitz in the Archives of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia". Bartonia (59): 125–128. ISSN 0198-7356. JSTOR 41610055.

- Karakehian, Jason M.; Burk, William R.; Pfister, Donald H. (June 2018). "New light on the mycological work of Lewis David von Schweinitz". IMA Fungus. 9 (1): A17–A35. doi:10.1007/BF03449476. ISSN 2210-6359. S2CID 190248487.

- Haines, John. "Women's history: Mary Banning". New York State Museum. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- New York State Museum. "Fungi: Mary Banning". Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Hewitt, David (2002). "Lewis David von Schweinitz's Mycological Illustrations". Bartonia (61): 48–53. ISSN 0198-7356. JSTOR 41610087.

- "Bard College Montgomery Place Campus Collection: Mushroom Drawings of Violetta White Delafield". www.jstor.org. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- Abir-Am, Pnina G.; Outram, Dorinda, eds. (1987). ""Chapter 5. Nineteenth-Century American Women Botanists: Wives, Widows, and Work" by Nancy G. Slack". Uneasy Careers and Intimate Lives: Women in Science, 1789–1979. pp. 77–103. ISBN 9780813512563. (p. 83)

- "Delafield Family Papers". Princeton University Library. Special Collection. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Fruiting Bodies: The Mycological Passions of John Cage (1912–1992) and Violetta White Delafield (1875–1949)". Libraries at Bard College. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Chimileski, Scott (2017). Life at the edge of sight : a photographic exploration of the microbial world. Roberto Kolter. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0-674-98246-8. OCLC 1003317651.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "PHOTOGRAPHY - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- "Photography Contest Rules - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Millman, Lawrence. "Mushroom Planet". FUNGI Magazine. Vol. 15, no. 3. pp. 22–23.

- Millman, Lawrence (2022). "Mushroom Planet". FUNGI Magazine. 15 (3): 23.

- "The Way Through the Woods: On Mushrooms and Mourning - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- "Shroomin' – A mushroom reading list | Washington State Magazine | Washington State University". Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- Bradbury, Ray (1962). ""Come into My Cellar"" (PDF). Galaxy Magazine.

- Wasson, R Gordon (7 April 1972). "The Death of Claudius Or Mushrooms For Murderers". Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University. 23 (3): 101–128. doi:10.5962/p.168556. ISSN 0006-8098. S2CID 87008723.

- Verran, Joanna (24 June 2021). "Using fiction to engage audiences with infectious disease: the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on participation in the Bad Bugs Bookclub". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 368 (12): fnab072. doi:10.1093/femsle/fnab072. ISSN 1574-6968. PMC 8344436. PMID 34113987.

- Popova, Maria (25 November 2019). "The Mushroom Hunters: Neil Gaiman's Subversive Feminist Celebration of Science and the Human Hunger for Truth, in a Gorgeous Animated Short Film". The Marginalian. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Guy, Nathaniel (2023). Kinoko: A window into the mystical world of Japanese mushrooms. Nathaniel Guy. ISBN 979-8987537633.

- Dugan, Frank M. (2008). Fungi in the ancient world: how mushrooms, mildews, molds, and yeast shaped the early civilizations of Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Near East. American Phytopathological Society. St, Paul, Minn.: APS Press. ISBN 978-0-89054-361-0. OCLC 193173263.

- "Myth & Mycelium — Myth & Mycelium". Sophie Strand Myth & Mycelium advaya. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Matthew 13:33

- Luke 12:1

- Berlant, Stephen R. (November 2005). "The entheomycological origin of Egyptian crowns and the esoteric underpinnings of Egyptian religion". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 102 (2): 275–288. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.028. PMID 16199133. S2CID 19297225.

- Dugan, Frank (Summer 2017). "Baba Yaga and the Mushroom". FUNGI Magazine. Vol. 10, no. 2. pp. 6–16.

- "Exhibition "The War of the Mushrooms" opens at the Ukrainian Museum". artdaily.com. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Dugan, Frank (2008). "Fungi, folkways and fairy tales: mushrooms & mildews in stories, remedies & rituals, from Oberon to the Internet". North American Fungi. 3: 23–72. doi:10.2509/naf2008.003.0074.

- Millman, Lawrence (2019). Fungipedia: a brief compendium of mushroom lore. Amy Jean Porter. Princeton, New Jersey. pp. 138–9. ISBN 978-0-691-19538-4. OCLC 1103605862.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Spooner B, Læssøe T (1994). "The folklore of 'Gasteromycetes'". Mycologist. 8 (3): 119–23. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(09)80157-2.

- Oso BA. (1975). "Mushrooms and the Yoruba people of Nigeria". Mycologia. 67 (2): 311–9. doi:10.2307/3758423. JSTOR 3758423. PMID 1167931. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- Oso BA. (1976). "Phallus aurantiacus from Nigeria". Mycologia. 68 (5): 1076–82. doi:10.2307/3758723. JSTOR 3758723. PMID 995138. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- "Why Jewish culture is mushrooming". www.thejc.com. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- "The dark side of funghi". www.thejc.com. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world : on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-16275-1. OCLC 894777646.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bone, Eugenia (2011). Mycophilia: revelations from the weird world of mushrooms. New York: Rodale. ISBN 978-1-60529-407-0. OCLC 707329318.

- Stamets, Paul (2005). Mycelium running: how mushrooms can help save the world. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1-299-16631-8. OCLC 842961074.

- McCoy, Peter (2016). Radical mycology: a treatise on seeing & working with fungi. Portland, Oregon. ISBN 978-0-9863996-0-2. OCLC 941779592.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Seifert, Keith A. (2022). The hidden kingdom of fungi : exploring the microscopic world in our forests, homes, and bodies. Rob Dunn. Vancouver. ISBN 978-1-77164-662-8. OCLC 1261880063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Catsoulis, Jeannette (10 October 2019). "'Fantastic Fungi' Review: The Magic of Mushrooms". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ""The Mushroom Speaks": le champignon est l'avenir de l'homme". Le Temps (in French). 2021-04-22. ISSN 1423-3967. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- "Page". Fungi Film Fest. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- "Film festival :: UK Fungus Day". www.ukfungusday.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022.

- "Psilocybin, the Mushroom, and Terence McKenna". www.vice.com. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- Bill Hicks,The Stoned Ape Theory, retrieved 6 December 2022

- "Mushrooms in Video Games". Fantastic Fungi. 15 February 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Gottesman, Sarah (3 January 2017). "Why Experimental Artist John Cage Was Obsessed with Mushrooms". Artsy. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- Sheldrake, Merlin (May 2020). Entangled life: how fungi make our worlds, change our minds & shape our futures. New York. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-525-51031-4. OCLC 1127137515.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Björk Excavates the Meaning Behind Fossora, Her "Mushroom Album"". Pitchfork. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- "Björk's New Album Is an Ode to Mushrooms". SURFACE. 2022-10-03. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "fossora | Björk". fossora.

- "Fungi is a Recording Artist & Freestyle Rap Magician from Pittsburgh, PA". FungiFlows.fun. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- "The Mushroom Whisperer". www.vice.com. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- "Song of the Mushrooms". The Mushroom Magazine. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "Funky fungi? Meet the musicians making melodies out of mushrooms". Classic FM. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "Can You Hear the Fungi Sing? | Singapore Art Museum". www.singaporeartmuseum.sg. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "Ep. 62: Myco Lyco - Fungal Frequencies, Biodata Sonification & the Music of Mushrooms (feat. Noah Kalos)". Mushroom Hour. 28 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Borhegyi, Stephan F. De (January 1963). "Pre-Columbian Pottery Mushrooms from Mesoamerica". American Antiquity. 28 (3): 328–338. doi:10.2307/278276. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 278276. S2CID 245676601.

- Hofmann, Albert (2010). LSD - mein Sorgenkind die Entdeckung einer "Wunderdroge" (3. Aufl ed.). Stuttgart. ISBN 978-3-608-94618-5. OCLC 695564591.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - El Parc Güell : guia. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. 1998. ISBN 84-7609-862-6. OCLC 39323956.

- Lawrence, Sandra (2022). The magic of mushrooms: fungi in folklore, superstition and traditional medicine. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. London. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-78739-906-8. OCLC 1328029699.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Triple Mycomorph | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Mind the Fungi. Vera Meyer, Regine Rapp, Technische Universität Berlin Universitätsbibliothek. Berlin. 2020. ISBN 978-3-7983-3168-6. OCLC 1229035875.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - "Feature Art Lab". futurium.de. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "Mind the Fungi". Art Laboratory Berlin. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- Ainsworth, G. C.; Webster, J.; Moore, D. (1996). Brief biographies of British mycologists. British Mycological Society. ISBN 0-9527704-0-7. OCLC 37448227.

- Livesey, James (16 October 2018). "Glass Models of Fungi". www.whipplemuseum.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Tribe, Henry T. (November 1998). "The Dillon Weston glass models of microfungi" (PDF). Mycologist. 12 (4): 169–173. doi:10.1016/s0269-915x(98)80074-8. ISSN 0269-915X.

- "Collection description: Glass botanical models of pathological fungi and photographic plates, by Dr. W. A. R. Dillon Weston". collections.whipplemuseum.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Pérez-Montes, Antonio; Rangel-Vargas, Esmeralda; Lorenzo, José Manuel; Romero, Leticia; Santos, Eva M (1 February 2021). "Edible mushrooms as a novel trend in the development of healthier meat products". Current Opinion in Food Science. 37: 118–124. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2020.10.004. ISSN 2214-7993. S2CID 225108583.

- Carrasco, Jaime; Preston, Gail M. (March 2020). "Growing edible mushrooms: a conversation between bacteria and fungi". Environmental Microbiology. 22 (3): 858–872. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14765. ISSN 1462-2912. PMID 31361932. S2CID 198997937.

- "How a Zombie Worm From Tibet Became an American Health Food Juggernaut". Bon Appétit. 13 March 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Meyer, Vera; Nevoigt, Elke; Wiemann, Philipp (1 April 2016). "The art of design". Fungal Genetics and Biology. The Era of Synthetic Biology in Yeast and Filamentous Fungi. 89: 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2016.02.006. ISSN 1087-1845. PMID 26968149.

- "Funky Funghy". Philipp Frank (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Guido, Giulia (25 February 2021). "Philipp Frank and his light installations | Collater.al". Collateral. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- Vaillancourt, Lisa (2018). "The Fungal Mating Game: A Simple Demonstration of the Genetic Regulation of Fungal Mating Compatibility". The Plant Health Instructor.

- Rokas, Antonis (30 October 2018). "Where sexes come by the thousands". The Conversation. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Cotter, Tradd (2014). Organic mushroom farming and mycoremediation : simple to advanced and experimental techniques for indoor and outdoor cultivation. White River Junction, Vermont. ISBN 978-1-60358-455-5. OCLC 877851800.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Go fish: Danish scientists work on fungi-based seafood substitute". The Guardian. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- Vander Kooi, Carl (February 2012). "Hieronymus Bosch and ergotism" (PDF). WMJ. 111 (1).

- "Meet the Luthier Growing Guitars with Mycelium". Ecovative. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Schwarze, Francis W. M. R.; Spycher, Melanie; Fink, Siegfried (2008). "Superior wood for violins--wood decay fungi as a substitute for cold climate". The New Phytologist. 179 (4): 1095–1104. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02524.x. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 18554266.

- Schwarze, Francis W. M. R.; Morris, Hugh (May 2020). "Banishing the myths and dogmas surrounding the biotech Stradivarius". Plants, People, Planet. 2 (3): 237–243. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10097. ISSN 2572-2611. S2CID 218824236.

- Simpson, Connor (8 September 2012). "How One Man Is Using Fungus to Change the Violin Industry". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- "32nd Bienal de São Paulo (2016) - Catalogue by Bienal São Paulo - Issuu". issuu.com. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- Lacey, Sharon (2018-04-24). ""Humanities through material engagement": Gediminas Urbonas on artistic research". Arts at MIT. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- Engage with fungi. Vera Meyer, Sven, ca. Jh Pfeiffer. Berlin. 2022. ISBN 978-3-98781-000-8. OCLC 1347218344.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Meyer, Vera (26 April 2019). "Merging science and art through fungi". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 6 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s40694-019-0068-7. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 6485050. PMID 31057802.

- Abhijith, R.; Ashok, Anagha; Rejeesh, C. R. (1 January 2018). "Sustainable packaging applications from mycelium to substitute polystyrene: a review". Materials Today: Proceedings. Second International Conference on Materials Science (ICMS2017) during 16 – 18 February 2017. 5 (1, Part 2): 2139–2145. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.211. ISSN 2214-7853.

- "Mycotecture (Phil Ross)". Design and Violence. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Stange, Stephanie; Wagenführ, André (18 March 2022). "70 years of wood modification with fungi". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00136-9. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8931968. PMID 35303960.

- Meyer, Vera (2022-03-01). "Connecting materials sciences with fungal biology: a sea of possibilities". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00137-8. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8889637. PMID 35232493.

- Almpani-Lekka, Dimitra; Pfeiffer, Sven; Schmidts, Christian; Seo, Seung-il (2021-11-19). "A review on architecture with fungal biomaterials: the desired and the feasible". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 8 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00124-5. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8603577. PMID 34798908.

- Tavares, Frank (10 January 2020). "Could Future Homes on the Moon and Mars Be Made of Fungi?". NASA. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Paganini, Romano (24 May 2016). "Der Pilz, aus dem die Mauern sind". Beobachter (in Swiss High German). Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Bayer, Eben. "The Mycelium Revolution Is upon Us". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- van den Brandhof, Jeroen G.; Wösten, Han A. B. (24 February 2022). "Risk assessment of fungal materials". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00134-x. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8876125. PMID 35209958.

- Vandelook, Simon; Elsacker, Elise; Van Wylick, Aurélie; De Laet, Lars; Peeters, Eveline (2021-12-20). "Current state and future prospects of pure mycelium materials". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 8 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00128-1. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8691024. PMID 34930476.

- "A fungal future". www.micropia.nl. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "dae.wiki". www.designacademy.nl. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Gamillo, Elizabeth. "This Mushroom-Based Leather Could Be the Next Sustainable Fashion Material". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- Haines, Anna. "Fungi Fashion Is Booming As Adidas Launches New Mushroom Leather Shoe". Forbes. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- "Stella McCartney to debut first-ever mushroom leather bag". Vogue Business. 2022-05-23. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- Rosen, Ellen (2022-12-14). "Are Mushrooms the Future of Alternative Leather?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- "It's this season's mush-have Hermès bag. And it's made from fungus". The Guardian. 2021-06-12. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- Robson, H. K. 2018. The Star Carr Fungi. In: Milner, N., Conneller, C. and Taylor, B. (eds.) Star Carr Volume 2: Studies in Technology, Subsistence and Environment, pp. 437–445. York: White Rose University Press. doi:10.22599/book2.q. Licence: CC BY-NC 4.0

- Cotter T. (2015). Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation: Simple to Advanced and Experimental Techniques for Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-60358-456-2.

- John Van Vliet (1999). Fly Fishing Equipment & Skills. Creative Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86573-100-4.

- Jon Beer (October 13, 2001). "Reel life: fomes fomentarius". The Telegraph.

- Greenberg J. (2014). Rivers of Sand: Fly Fishing Michigan and the Great Lakes Region. Lyons Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4930-0783-7.

- Pegler D. (2001). "Useful fungi of the world: Amadou and Chaga". Mycologist. 15 (4): 153–154. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(01)80004-5.

In Germany, this soft, pliable 'felt' has been harvested for many years for a secondary function, namely in the manufacture of hats, dress adornments and purses.

- Alice Klein (Jun 16, 2018). "Vegan-friendly fashion is actually bad for the environment". New Scientist.

- Joe Rogan Experience #1035 - Paul Stamets on YouTube

- Cypress Hansen, Century-Old Textiles Woven from Fascinating Fungus, Scientific American, June 2021.

- Matthew Kronsberg, Leather May Be Most Viable Vegan Alternative to Cowhide, Bloomberg, July 2022.

- Meyer, V (2022). "Connecting materials sciences with fungal biology: a sea of possibilities". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00137-8. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8889637. PMID 35232493.

- Federica Maccotta, | Le case del futuro? Saranno fatte di funghi, Wired Italy, August 2022.

- Eben Bayer, | The Mycelium Revolution Is upon Us, Scientific American, July 2019.

- Frank Tavares, | Could Future Homes on the Moon and Mars Be Made of Fungi?, nasa.gov, Jan 2020.

- Furci, Giuliana (11 November 2021). "The earth's secret miracle worker is not a plant or an animal. It's fungi | Giuliana Furci". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- "Go fish: Danish scientists work on fungi-based seafood substitute". The Guardian. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Feldman, Amy. "Bioengineered Bacon? The Entrepreneur Behind Mushroom-Root Packaging Says His Test Version Is Tasty". Forbes. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Sorvino, Chloe. "Maker Of Mushroom-Sourced Bacon Raises $40 Million To Reach Grocers At Scale". Forbes. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "Fungus Born of Yellowstone Hot Spring Makes Menu at Le Bernardin". Bloomberg.com. 19 July 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "ASM Agar Art Contest | Overview". ASM.org. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- "This gorgeous art was made with a surprising substance: live bacteria". Science. 2019-11-20. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- "Painting With Penicillin: Alexander Fleming's Germ Art". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- "Alexander Fleming « Microbial Art". www.microbialart.com. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- "Urbonas Studio's 'Mushroom Power Plant' at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm – Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT)". Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- Sharma, Sunanda; Meyer, Vera (10 January 2022). "The colors of life: an interdisciplinary artist-in-residence project to research fungal pigments as a gateway to empathy and understanding of microbial life". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00130-7. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8744264. PMID 35012670.

- Watlington, Emily (29 December 2021). "Mushrooms as Metaphors". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Introduction to Fungi". Introduction to Fungi. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- "How to: Spore Prints - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- "Vieni nella mia cantina, breve racconto di Ray Bradbury adattato a fumetti da Dave Gibbons". www.slumberland.it. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- Britton, Scott J; Rogers, Lisa J; White, Jane S; Maskell, Dawn L (25 November 2022). "HYPHAEdelity: a quantitative image analysis tool for assessing peripheral whole colony filamentation". FEMS Yeast Research. 22 (1): foac060. doi:10.1093/femsyr/foac060. ISSN 1567-1364. PMC 9697609. PMID 36398755.

- "History and Art of Mushroom Dyes for Color - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- Dvoráková, Marie, Who's Who in Mycology (Animation, Short, Adventure), retrieved 16 December 2022

- Bunyard, Britt. "Bookshelf Fungi - Book review of 'The Slime Mold Murder' by Ellen King Rice". FUNGI Magazine. 15 (2): 62.

- Bunyard, Britt. "Bookshelf Fungi - Book review of 'Lichenwald' by Ellen King Rice". FUNGI Magazine. 14 (1): 48.

- "Wall full of 'cuddly' fungi in ARTIS-Micropia". www.micropia.nl. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- "De schoonheid van schimmels in tafelkleden". EWmagazine.nl (in Dutch). 3 February 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- Binsbergen, Sarah Van (25 February 2021). "Schimmels vies of lelijk? Lizan Freijsen toont juist hun schoonheid bij Artis/Micropia". de Volkskrant (in Dutch). Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- "Emma Sicher makes eco-friendly food packaging from fermented bacteria and yeast". Dezeen. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- Newell-Hanson, Alice (13 September 2019). "The Sculptor Making Massive, Moldy Fruits From Gemstones". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- "Kathleen Ryan | Liverpool Biennial of Contemporary Art". www.biennial.com. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- Penner, Joel; Penner, Joel; Sigrithur, Anna, Wrought (Documentary, Animation, Short), retrieved 15 December 2022