Gender inequality

Gender inequality is the social phenomenon in which people are not treated equally on the basis of gender. This inequality can be caused by gender discrimination or sexism. The treatment may arise from distinctions regarding biology, psychology, or cultural norms prevalent in the society. Some of these distinctions are empirically grounded, while others appear to be social constructs. While current policies around the world cause inequality among individuals, it is women who are most affected. Gender inequality weakens women in many areas such as health, education, and business life.[1] Studies show the different experiences of genders across many domains including education, life expectancy, personality, interests, family life, careers, and political affiliation. Gender inequality is experienced differently across different cultures and also affects non-binary people.

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Masculism |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

Sex differences

Biology

Natural differences exist between the sexes based on biological and anatomic factors, mostly differing reproductive roles. These biological differences include chromosomes and hormonal differences.[2] There is a natural difference also in the relative physical strengths (on average) of the sexes, both in the lower body and more pronouncedly in the upper-body, though this does not mean that any given man is stronger than any given woman.[3][4] Men, on average, are taller, which provides both advantages and disadvantages.[5] Women, on average, live significantly longer than men,[6] though it is not clear to what extent this is a biological difference - see Life expectancy. Men have larger lung volumes and more circulating blood cells and clotting factors, while women have more circulating white blood cells and produce antibodies faster.[7] Differences such as these are hypothesized to be an adaptation allowing for sexual specialization.[8]

Psychology

Prenatal hormone exposure influences the extent to which a person exhibits typical masculine or feminine traits.[9][10] Negligible differences between males and females exist in general intelligence.[11] Women are significantly less likely to take risks than men.[12] Men are also more likely than women to be aggressive, a trait influenced by prenatal and possibly current androgen exposure.[13][14] It has been theorized that these differences combined with physical differences are an adaptation representing sexual division of labour.[8] A second theory proposes sex differences in intergroup aggression represent adaptations in male aggression to allow for territory, resource and mate acquisition.[7] Females are (on average) more empathetic than males, though this does not mean that any given woman is more empathetic than any given man.[15] Men and women have better visuospatial and verbal memory, respectively. These changes are influenced by the male sex hormone testosterone, which increases visuospatial memory in both genders when administered.[16]

From birth, males and females are socialised differently, and experience different environments throughout their lives. Due to societal influence, gender often greatly influences many major characteristics in life; such as personality.[17] Males and females are led on different paths due to the influences of gender role expectations and gender role stereotypes often before they are able to choose for themselves. For instance, in Western societies,the colour blue is commonly associated with boys, and they are often given toys that are associated with traditional masculine roles, such as machines and trucks. Girls are associated with the colour pink, and are given toys related to traditional feminine roles, such as dolls, dresses, and dollhouses. These influences by parents or other adult figures in the child's life encourage them to fit into these roles.[18] This tends to affect personality, career paths, or relationships. Throughout life, males and females are seen as two very different species who have very different personalities and should stay on separate paths.[19]

Researcher Janet Hyde found that, although much research has traditionally focused on the differences between the genders, they are actually more alike than different, which is a position proposed by the gender similarities hypothesis.[20]

In the workplace

Income disparities linked to job stratification

Across the board, a number of industries are stratified across the genders. This is the result of a variety of factors. These include differences in education choices, preferred job and industry, work experience, number of hours worked, and breaks in employment (such as for bearing and raising children). Men also typically go into higher paid and higher risk jobs when compared to women. These factors result in 60% to 75% difference between men's and women's average aggregate wages or salaries, depending on the source. Various explanations for the remaining 25% to 40% have been suggested, including women's lower willingness and ability to negotiate salary and sexual discrimination.[21][22][23] According to the European Commission direct discrimination only explains a small part of gender wage differences.[24][25]

In the United States, the average female's unadjusted annual salary has been cited as 78% of that of the average male.[26] However, multiple studies from OECD, AAUW, and the US Department of Labor have found that pay rates between males and females varied by 5–6.6% or, females earning 94 cents to every dollar earned by their male counterparts, when wages were adjusted to different individual choices made by male and female workers in college major, occupation, working hours, and maternal/parental leave.[27] The remaining 6% of the gap has been speculated to originate from deficiency in salary negotiating skills and sexual discrimination.[27][28][29][30]

Human capital theories refer to the education, knowledge, training, experience, or skill of a person which makes them potentially valuable to an employer. This has historically been understood as a cause of the gendered wage gap but is no longer a predominant cause as women and men in certain occupations tend to have similar education levels or other credentials. Even when such characteristics of jobs and workers are controlled for, the presence of women within a certain occupation leads to lower wages. This earnings discrimination is considered to be a part of pollution theory. This theory suggests that jobs which are predominated by women offer lower wages than do jobs simply because of the presence of women within the occupation. As women enter an occupation, this reduces the amount of prestige associated with the job and men subsequently leave these occupations.[31] The entering of women into specific occupations suggests that less competent workers have begun to be hired or that the occupation is becoming deskilled. Men are reluctant to enter female-dominated occupations because of this and similarly resist the entrance of women into male-dominated occupations.[32]

The gendered income disparity can also be attributed in part to occupational segregation, where groups of people are distributed across occupations according to ascribed characteristics; in this case, gender.[33] Occupational gender segregation can be understood to contain two components or dimensions; horizontal segregation and vertical segregation. With horizontal segregation, occupational sex segregation occurs as men and women are thought to possess different physical, emotional, and mental capabilities. These different capabilities make the genders vary in the types of jobs they are suited for. This can be specifically viewed with the gendered division between manual and non-manual labor. With vertical segregation, occupational sex segregation occurs as occupations are stratified according to the power, authority, income, and prestige associated with the occupation and women are excluded from holding such jobs.[32]

As women entered the workforce in larger numbers since the 1960s, occupations have become segregated based on the amount femininity or masculinity presupposed to be associated with each occupation. Census data suggests that while some occupations have become more gender integrated (mail carriers, bartenders, bus drivers, and real estate agents), occupations including teachers, nurses, secretaries, and librarians have become female-dominated while occupations including architects, electrical engineers, and airplane pilots remain predominately male in composition.[34] Based on the census data, women occupy the service sector jobs at higher rates than men. Women's overrepresentation in service sector jobs, as opposed to jobs that require managerial work acts as a reinforcement of women and men into traditional gender roles that causes gender inequality.[35]

"The gender wage gap is an indicator of women's earnings compared with men's. It is figured by dividing the average annual earnings for women by the average annual earnings for men." (Higgins et al., 2014) Scholars disagree about how much of the male-female wage gap depends on factors such as experience, education, occupation, and other job-relevant characteristics. Sociologist Douglas Massey found that 41% remains unexplained,[32] while CONSAD analysts found that these factors explain between 65.1 and 76.4 percent of the raw wage gap.[37] CONSAD also noted that other factors such as benefits and overtime explain "additional portions of the raw gender wage gap".

The glass ceiling effect is also considered a possible contributor to the gender wage gap or income disparity. This effect suggests that gender provides significant disadvantages towards the top of job hierarchies which become worse as a person's career goes on. The term glass ceiling implies that invisible or artificial barriers exist which prevent women from advancing within their jobs or receiving promotions. These barriers exist in spite of the achievements or qualifications of the women and still exist when other characteristics that are job-relevant such as experience, education, and abilities are controlled for. The inequality effects of the glass ceiling are more prevalent within higher-powered or higher income occupations, with fewer women holding these types of occupations. The glass ceiling effect also indicates the limited chances of women for income raises and promotion or advancement to more prestigious positions or jobs. As women are prevented by these artificial barriers, from either receiving job promotions or income raises, the effects of the inequality of the glass ceiling increase over the course of a woman's career.[38]

Statistical discrimination is also cited as a cause for income disparities and gendered inequality in the workplace. Statistical discrimination indicates the likelihood of employers to deny women access to certain occupational tracks because women are more likely than men to leave their job or the labor force when they become married or pregnant. Women are instead given positions that dead-end or jobs that have very little mobility.[39]

In developing countries such as the Dominican Republic, female entrepreneurs are statistically more prone to failure in business. In the event of a business failure women often return to their domestic lifestyle despite the absence of income. On the other hand, men tend to search for other employment as the household is not a priority.[40]

The gender earnings ratio suggests that there has been an increase in women's earnings comparative to men. Men's plateau in earnings began after the 1970s, allowing for the increase in women's wages to close the ratio between incomes. Despite the smaller ratio between men and women's wages, disparity still exists. Census[41] data suggests that women's earnings are 71 percent of men's earnings in 1999.[34]

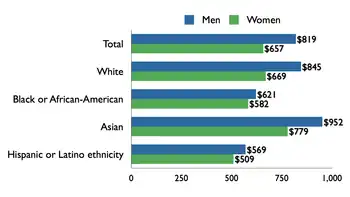

The gendered wage gap varies in its width among different races. Whites comparatively have the greatest wage gap between the genders. With whites, women earn 78% of the wages that white men do. With African Americans, women earn 90% of the wages that African American men do.

There are some exceptions where women earn more than men: According to a survey on gender pay inequality by the International Trade Union Confederation, female workers in the Gulf state of Bahrain earn 40 percent more than male workers.[42]

In 2014, a report by the International Labor Organization (ILO) reveals the wage gap between Cambodian women factory workers and other male counterparts. There was a US$25 monthly pay difference, suggesting that women have a much lower power and being devalued not only at home but also in the workplace.[43]

Professional education and careers

The gender gap has narrowed to various degrees since the mid-1960s. Where some 5% of first-year students in professional programs were female in 1965, by 1985 this number had jumped to 40% in law and medicine, and over 30% in dentistry and business school.[44] Before the highly effective birth control pill was available, women planning professional careers, which required a long-term, expensive commitment, had to "pay the penalty of abstinence or cope with considerable uncertainty regarding pregnancy".[45] This control over their reproductive decisions allowed women to more easily make long-term decisions about their education and professional opportunities. Women are highly underrepresented on boards of directors and in senior positions in the private sector.[46] Gender inequality in professional education is a global issue. Robet Meyers and Amy Griffin studied the underrepresentation of female international students in higher education. In 2019, on 43.6% of international students in the United States were women.[47] The disparity is even greater in the STEM field.

Additionally, with reliable birth control, young men and women had more reason to delay marriage. This meant that the marriage market available to any women who "delay[ed] marriage to pursue a career ... would not be as depleted. Thus the Pill could have influenced women's careers, college majors, professional degrees, and the age at marriage."[48]

Studies on sexism in science and technology fields have produced conflicting results. Moss-Racusin et al. found that science faculty of both sexes rated a male applicant as significantly more competent and hireable than an identical female applicant. These participants also selected a higher starting salary and offered more career mentoring to the male applicant.[49] Williams and Ceci, however, found that science and technology faculty of both sexes "preferred female applicants 2:1 over identically qualified males with matching lifestyles" for tenure-track positions.[50] Studies show parents are more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in a science, technology, engineering or mathematics field – even when their 15-year-old boys and girls perform at the same level in mathematics.[51] There are more men than women trained as dentists, this trend has been changing.[52]

A survey by the U.K. Office for National Statistics in 2016 showed that in the health sector 56% of roles are held by women, while in teaching it is 68%.[53] However equality is less evident in other area; only 30% of M.P.s are women and only 32% of finance and investment analysts. In the natural and social sciences 43% of employees are women, and in the environmental sector 42%.[54]

In an article by MacNell et al. (2014), researchers used an online course and falsified the names of assistant teachers to make students believe they had either a female or a male teaching assistant. At the end of the semester, they had the students complete a course evaluation. Regardless of whether the teaching assistant was actually male or female, assistants who were perceived as female received lower course evaluations overall with distinctly lower ratings in areas of promptness, praise, fairness, and professionalism.[55]

In an article titled "Gender Differences in Education, Career Choices and Labor Market Outcomes on a Sample of OECD Countries", the researchers focused their work on how both men and women differ from their studies, their focuses, and their objectives within their work. Women are seen to have higher chances to choose the humanities and health fields while decreasing their opportunities in the sciences and social sciences fields. This indicates that there is a larger impact on men's decisions about fields of study.

Customer preference studies

A 2010 study conducted by David R. Hekman and colleagues found that customers, who viewed videos featuring a black male, a white female, or a white male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer, were 19 percent more satisfied with the white male employee's performance.[56][57][58][59][60]

This discrepancy with race can be found as early as 1947, when Kenneth Clark conducted a study in which black children were asked to choose between white and black dolls. White male dolls were the ones children preferred to play with.[61][62]

Gender pay differences

Gender inequalities still exist as social problems and are still growing in places.[63][64] In 2008, recently qualified female doctors in New York State had a starting salary $16,819 less than their male counterparts. An increase compared to the $3,600 difference of 1999. The pay discrepancy could not be explained by specialty choice, practice setting, work hours, or other characteristics. Nonetheless, some potentially significant factors like family or marital status were not evaluated.[65] A case study carried out on Swedish medical doctors showed that the gender wage gap among physicians was greater in 2007 than in 1975.[66]

Wage discrimination is when an employer pays different wages to two seemingly similar employees, usually on the basis of gender or race. Kampelmann and Rycx (2016) explain two different explanations for the differences observed in wages.[67] They explain that employer tastes and preferences for foreign workers and/or customers can translate into having a lower demand for them as a whole and as a result offering them lower wages, as well as the differences in career dynamics, whereas, if there is large differences between immigrant workers and "native" workers, it could lead to wage discrimination for immigrant workers.[67] Within the discrimination of domestic to foreign workers there is also discrimination among foreign workers based on gender.[67] Female migrant workers are faced with a "triple-discrimination".[68] This "triple-discrimination" states that women foreign workers are more at risk to experience discrimination because they are women, unprotected workers, and migrant workers.[68]

At home

Gender roles in parenting and marriage

Gender roles are heavily influenced by biology, with male-female play styles correlating with sex hormones,[69] sexual orientation, aggressive traits,[70] and pain.[71] Furthermore, females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia demonstrate increased masculinity[72] and it has been shown that rhesus macaque children exhibit preferences for stereotypically male and female toys.[73]

Gender inequality in relationships

Gender inequality in relationships has been growing over the years but for the majority of relationships, the power lies with the male.[74] Even now men and women present themselves as divided along gender lines. A study done by Szymanowicz and Furnham, looked at the cultural stereotypes of intelligence in men and women, showing the gender inequality in self-presentation.[75] This study showed that females thought if they revealed their intelligence to a potential partner, then it would diminish their chance with him. Men however would much more readily discuss their own intelligence with a potential partner. Also, women are aware of people's negative reactions to IQ, so they limit its disclosure to only trusted friends. Females would disclose IQ more often than men with the expectation that a real true friend would respond in a positive way. Intelligence continues to be viewed as a more masculine trait, than feminine trait. The article suggested that men might think women with a high IQ would lack traits that were desirable in a mate such as warmth, nurturance, sensitivity, or kindness. Another discovery was that females thought that friends should be told about one's IQ more so than males. However, males expressed doubts about the test's reliability and the importance of IQ in real life more so than women. The inequality is highlighted when a couple starts to decide who is in charge of family issues and who is primarily responsible for earning income. For example, in Londa Schiebinger's book, "Has Feminism Changed Science?", she claims that "Married men with families on average earn more money, live longer and happier, and progress faster in their careers", while "for a working woman, a family is a liability, extra baggage threatening to drag down her career."[76] Furthermore, statistics had shown that "only 17 percent of the women who are full professors of engineering have children, while 82 percent of the men do."[76]

Attempts in equalizing household work

Despite the increase in women in the labor force since the mid-1900s, traditional gender roles are still prevalent in American society. Many women are expected to put their educational and career goals on hold in order to raise a family, while their husbands become primary breadwinners. However, some women choose to work and also fulfill a perceived gender role of cleaning the house and caring for children. Despite the fact that certain households might divide chores more evenly, there is evidence supporting the issue that women have continued being the primary care-giver in family life even if they work full-time jobs. This evidence suggests that women who work outside the home often put an extra 18 hours a week doing household or childcare related chores as opposed to men who average 12 minutes a day in childcare activities.[77] One study by van Hooff showed that modern couples, do not necessarily purposefully divide things like household chores along gender lines, but instead may rationalize it and make excuses.[74] One excuse used is that women are more competent at household chores and have more motivation to do them, and some say the jobs men have are much more demanding.

In The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, Wendell Berry wrote in the 1970s that the "home became a place for the husband to go when he was not working ... it was the place where the wife was held in servitude."[78] A study conducted by Sarah F. Berk, called "The Gender Factory", researched this aspect of gender inequality as well. Berk found that "household labor is about power".[79] The reason the spouse performing less housework is not the spouse in power is simple; they have more free time than their counterpart; therefore, they are able to do more of what they want after the average workday.

Gender roles have changed drastically over the past few decades. In an article taking the time period of 1920–1966, data was recorded which surmised that women spent most of their time tending the home and family. A study assessing changing gender roles between males and females showed that as women begin to spend less time in the house, men are taking over the role of the caretaker and spending more time with children as compared to their female counterparts. Robin A. Douthitt, author of the article, "The Division of Labor Within the Home: Have Gender Roles Changed?" concluded by saying, "(1) men do not spend significantly more time with children when their wives are employed and (2) employed women spend significantly less time in child care than their full-time homemaker counterparts (3) over a 10-year period both mothers and fathers are spending more total time with children." (703).

Women bear a disproportionate burden when it comes to unpaid work. In the Asia and Pacific region, women spend 4.1 times more time in unpaid work than men do.[80] Additionally, looking at 2019 data by the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, the average time women spent in unpaid work is 264 minutes per day compared to men who spent 136 minutes per day.[81] Although men spend more time in paid work, women still spend more time, in general, doing both paid and unpaid work. The numbers are 482.5 minutes per day for women and 454.4 minutes per day for men.[81] These statistics show us that there is a double burden for women.

Gender inequalities in relation to technology

One survey showed that men rate their technological skills in activities such as basic computer functions and online participatory communication higher than women. However, this study was a self-reporting study, where men evaluate themselves on their own perceived capabilities. It thus is not data based on actual ability, but merely perceived ability, as participants' ability was not assessed. Additionally, this study is inevitably subject to the significant bias associated with self-reported data.[82]

In contrary to such findings, a carefully controlled study that analyzed data sets from 25 developing countries led to the consistent finding that the reason why fewer women access and use digital technology is a direct result of their unfavorable conditions and ongoing discrimination with respect to employment, education and income.[83] When controlling for these variables, women turn out to be more active users of digital tools than men. This turns the alleged digital gender divide into an opportunity: given women's affinity for information and communications technology (ICT), and given that digital technologies are tools that can improve living conditions, ICT represents a concrete and tangible opportunity to tackle longstanding challenges of gender inequalities in developing countries, including access to employment, income, education and health services.[84][85]

Women are often drastically underrepresented within university technology and ICT focused programs while being overrepresented within social programs and humanities. Although data has shown women in western society generally outperform men in higher education, the labor markets of women often provide less opportunity and lower wages than that of men. Gender stereotypes and expectations may have an influence on the underrepresentation of women within technology and ICT focused programs and careers.[84][85] Females are also underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) at all levels of society. Fewer females are completing STEM school subjects, graduating with STEM degrees, being employed as STEM professionals, and holding senior leadership and academic positions in STEM. The gender pay gap, family role expectations, lack of visible role models or mentors, discrimination and harassment, and bias in hiring and promotion practices exacerbate this problem.[86]

Through socialization, women may feel obligated to choose programs with characteristics that emulate gender roles and stereotypes. Studies have shown domestic expectations may also lead to less opportunities in professional progression within the technology and ICT industry. Workplace practices of technology industries often include long, demanding hours which often conflict with gendered domestic expectations. This conflict leads to less opportunity and women opting for less demanding jobs. Gendered roles and expectations may cause discriminatory tendencies during the hiring process in which employers are reluctant to hire women as a way to avoid extra costs and benefits. Tech employers reluctance to hire women result in placing them in less demanding and opportune jobs, situating female employees in lower positions that are difficult to advance in. The lack of women and the existence of gender stereotypes within the technology industry often lead to discrimination and marginalization of women by colleagues and co-workers. Women often feel as though they are not taken seriously or feel unheard. Discrimination and gendered expectations often prevent or create difficulties for women to obtain higher positions within technology companies.[84][85]

Energy poverty

Energy poverty is defined as lacking access to the affordable sustainable energy service.[87] Geographically, it is unevenly distributed in developing and developed countries.[88] In 2019, there were an estimated 770 million people who have no access to electricity, with approximately 95% distributed in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.[89]

In developing countries, poor women and girls living in the rural areas are significantly affected by energy poverty, because they are usually responsible for providing the primary energy for households.[90] In developed countries, old women living alone are mostly affected by energy poverty due to the low income and high cost of energy service.[91]

Even though energy access is an important climate change adaptation tool especially for maintaining health (i.e. access to air conditioning, information etc.), a systematic review published in 2019 found that research does not account for these effects onto vulnerable populations like women.[92]Property inheritance

Many countries have laws that give less inheritance of the ancestral property for women compared to men.[93][94]

Structural marginalization

Gender inequalities often stem from social structures that have institutionalized conceptions of gender differences.

Marginalization occurs on an individual level when someone feels as if they are on the fringes or margins of their respective society. This is a social process and displays how current policies in place can affect people. For example, media advertisements display young girls with easy bake ovens (promoting being a housewife) as well as with dolls that they can feed and change the diaper of (promoting being a mother).

Gender stereotypes

Cultural stereotypes, which can dictate specific roles, are engrained in both men and women and these stereotypes are a possible explanation for gender inequality and the resulting gendered wage disparity. Women have traditionally been viewed as being caring and nurturing and are designated to occupations which require such skills. While these skills are culturally valued, they were typically associated with domesticity, so occupations requiring these same skills are not economically valued. Men have traditionally been viewed as the main worker in the home, so jobs held by men have been historically economically valued and occupations predominated by men continue to be economically valued and earn higher wages.[32]

Gender Stereotypes influenced greatly by gender expectations, different expectations on gender influence how people determine their roles, appearance, behaviors, etc.[95] When expectations of gender roles deeply rooted in people's mind, people' values and ideas started to be influenced and leading to situation of stereotypes, which actualize their ideas into actions and perform different standards labelling the behaviors of people. Gender stereotypes limit opportunities of different gender when their performance or abilities were standardizing according to their gender-at-birth, that women and men may encounter limitations and difficulties when challenging the society through performing behaviors that their gender is "not supposed" to perform. For example, men may receive judgments when they are trying to stay at home and finish housework and support their wives to go out and work instead, as men are expected to be work outside for earning money for the family. The traditional concepts of gender stereotypes are being challenged nowadays in different societies and improvement could be observed that men could also be responsible for housework, women could also be construction worker in some societies. It is still a long process when traditional concepts and values have deep-rooted in people's mind, that higher acceptance towards gender roles and characteristics is homely to be gradually developed.

Biological fertilisation stereotypes

Bonnie Spanier coined the term hereditary inequality.[96] Her opinion is that some scientific publications depict human fertilization such that sperms seem to actively compete for the "passive" egg, even though in reality it is complicated (e.g. the egg has specific active membrane proteins that select sperm etc.)

Sexism and discrimination

Gender inequality can further be understood through the mechanisms of sexism. Discrimination takes place due to the prejudiced treatment of men and women based on gender alone. Sexism occurs when men and women are framed within two dimensions of social cognition.

Discrimination also plays out with networking and in preferential treatment within the economic market. Men typically occupy positions of power in society. Due to socially accepted gender roles or preference to other men, males in power are more likely to hire or promote other men, thus discriminating against women.[32]

In the criminal justice system

A 2008 study of three US district courts gave some explanations for gender disparity in sentencing: 1) that women are sentenced more leniently than men because they are convicted of less serious crimes and have less serious criminal records than men; that judges take personal factors relating to defendants (e.g. family responsibilities) into account; 2) that judges exercise chivalry or paternalism towards women in ways that discriminate against men; and 3) that apparent disparities are caused by the intersection of other factors, such as race (as data shows it is only white women rather than women of color that benefit from disparities).The study concluded that the second first explanation is not evidenced in their data, but were unable to confirm the other two.[97] Sonja B. Starr conducted a study in the US, published in 2012, that found that the prison sentences that men serve are on average 63% longer than those that women serve when controlling for arrest offense and criminal history.[98] Men's rights advocates have argued that men being over-represented in both those who commit murder and the victims of murder is evidence that men are being harmed by outmoded cultural attitudes.[99]

In 2022, Vicki Dabrowki and Emma Milne assessed female health care in the prison system in the United Kingdom. They found that there was an inconsistency in female and reproductive healthcare across prisons. More specifically, imprisoned women who had given birth reported feeling isolated and without access to healthcare professionals. Additionally, they reported a lack of access to feminine hygiene products.[100]

In a report by the Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress, researchers found that transgender people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. 21% of transgender women reported that they spent time in jail compared to 5% of all U.S. adults. The reason for this disproportionate rate was stated to be because transgender people are more likely to be put in vulnerable situations due to gender discrimination. Transgender people are more likely to face discrimination in the domains of housing, employment, healthcare, and identification documents, leading to higher interactions with the criminal justice system.[101] The report also found transgender women are more likely to experience gendered violence while in prison. When transgender women were placed in men's prisons in California, 59% reported that they had been sexually assaulted compared to the 4.4% of all male-respondents. Otherwise said, Transgender women are 13 times more likely to be assaulted than incarcerated men.[102]

In television and film

The New York Film Academy took a closer look at the women in Hollywood and gathered statistics from the top 500 films from 2007 to 2012, for their history and achievements, or lack of.

There was a 5:1 ratio of men to women working in films. 30.8% of women having speaking characters, who may or may not have been a part of the 28.8% of women who were written to wear revealing clothing compared to the 7% of men who did, or the 26.2% of women who wore little to no clothing opposed to the 9.4% of men who did the same.[103] A study analyzing five years of text from over 2,000 news sources found a similar 5:1 ratio of male to female names overall, and 3:1 for names in entertainment.[104]

Hollywood actresses are paid less than actors. Topping Forbes' highest paid actors list of 2013 was Robert Downey Jr. with $75 million. Angelina Jolie topped the highest paid actresses list with $33 million,[105] which tied with Denzel Washington ($33 million) and Liam Neeson ($32 million), who were the last two on the top ten highest paid actors list.[106]

In the 2013 Academy Awards, 140 men were nominated for an award, but only 35 women were nominated. No woman was nominated for directing, cinematography, film editing, writing (original screenplay), or original score that year. Since the Academy Awards began in 1929, only seven women producers have won the Best Picture category (all of whom were co-producers with men), and only eight women have been nominated for Best Original Screenplay. Lina Wertmuller (1976), Jane Campion (1994), Sofia Coppola (2004), and Kathryn Bigelow (2012) were the only four women to be nominated for Best Director, with Bigelow being the first woman to win for her film The Hurt Locker. The Academy Awards' voters are 77% male.[103]

A group of Hollywood actors have launched their own social movement titled #AskMoreOfHim. This movement is built on the basis of men speaking out against sexual misconduct against females.[107] A number of male activists, specifically in the film industry, have signed an open letter explaining their responsibility in the ownership of their actions, as well as calling out the actions of others. The letter has been signed and supported by Friends actor David Schwimmer, shown above, among many others. The Hollywood Reporter published their support saying, "We applaud the courage and pledge our support to the courageous women — and men, and gender non-conforming individuals — who have come forward to recount their experiences of harassment, abuse and violence at the hands of men in our country. As men, we have a special responsibility to prevent abuse from happening in the first place ... After all, the vast majority of sexual harassment, abuse and violence is perpetrated by men, whether in Hollywood or not."[108] This accountability is set to change the way women are seen and treated in the film and television industry, hopefully ending in the closing of the gap women are experiencing in pay, promotion, and overall respect. This initiative was created in response to the #MeToo movement.[109] The #MeToo movement, started by a single tweet, asked women to share their stories of sexual assault against men in a professional setting.[110] Within one day, 30,000 women had used the hashtag sharing their stories. Many women feel as if they have more power in their voices than they ever had and are choosing to make personal claims that may have been brushed under the rug prior to the internet culture we're now living in. According to Time magazine, 95% of women in the film and entertainment industry report being sexually harassed by men in their industry.[111] In addition to the #MeToo movement, women in industry are using #TimesUp, with the goal of aiming to help prevent sexual harassment in the workplace for victims who cannot afford their own resources.[112]

In sports

The media gives more weight to men in sports news: according to a study by Sports Illustrated on the news in the sports media, women's sports account for only 5.7% of the news in the media by ESPN.[1]

Another problem that has been causing increasing controversy lately is wage inequality. The fact that male athletes earn more money than females in almost all sports branches is the focus of discussion. The argument most often presented as the reason for this issue is that men's sports provide more income. However, according to the arguments that offer more realistic evaluations, women and men are not given equal opportunities in the field of sports, and women start and continue sports at a disadvantage. Some work has been done recently to prevent this inequality. According to the statements made, countries such as the United States, Spain, Sweden and Brazil announced that men and women national football team athletes will receive equal pay. It can be said that these developments are the initial steps to end gender inequality in sports.[3][4]

Impact and counteractions

Gender inequality and discrimination are argued to cause and perpetuate poverty and vulnerability in society as a whole.[113] Household and intra-household knowledge and resources are key influences in individuals' abilities to take advantage of external livelihood opportunities or respond appropriately to threats.[113] High education levels and social integration significantly improve the productivity of all members of the household and improve equity throughout society. Gender Equity Indices seek to provide the tools to demonstrate this feature of poverty.[113]

Poverty has many different factors, one of which is the gender wage gap. Women are more likely to be living in poverty and the wage gap is one of the causes.[114]

There are many difficulties in creating a comprehensive response.[115] It is argued that the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) fail to acknowledge gender inequality as a cross-cutting issue. Gender is mentioned in MDG3 and MDG5: MDG3 measures gender parity in education, the share of women in wage employment and the proportion women in national legislatures.[113] MDG5 focuses on maternal mortality and on universal access to reproductive health.[113] These targets are significantly off-track.[115]

Addressing gender inequality through social protection programmes designed to increase equity would be an effective way of reducing gender inequality, according to the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).[115] Researchers at the ODI argue for the need to develop the following in social protection in order to reduce gender inequality and increase growth:[113]

- Community childcare to give women greater opportunities to seek employment

- Support parents with the care costs (e.g. South African child/disability grants)

- Education stipends for girls (e.g. Bangladesh's Girls Education Stipend scheme)

- Awareness-raising regarding gender-based violence, which has surged globally in recent years,[116][117] and other preventive measures, such as financial support for women and children escaping abusive environments (e.g. NGO pilot initiatives in Ghana)

- Inclusion of programme participants (women and men) in designing and evaluating social protection programmes

- Gender-awareness and analysis training for programme staff

- Collect and distribute information on coordinated care and service facilities (e.g. access to micro-credit and micro-entrepreneurial training for women)

- Developing monitoring and evaluation systems that include sex-disaggregated data

The ODI maintains that society limits governments' ability to act on economic incentives.[115]

NGOs tend to protect women against gender inequality and structural violence.

During war, combatants primarily target men. Both sexes die however, due to disease, malnutrition and incidental crime and violence, as well as the battlefield injuries which predominately affect men.[118] A 2009 review of papers and data covering war related deaths disaggregated by gender concluded "It appears to be difficult to say whether more men or women die from conflict conditions overall."[119] The ratio also depends on the type of war, for example in the Falklands War 904 of the 907 dead were men. Conversely figures for war deaths in 1990, almost all relating to civil war, gave ratios in the order of 1.3 males per female.

Another opportunity to tackle gender inequality is presented by modern information and communication technologies. In a carefully controlled study,[83] it has been shown that women embrace digital technology more than men. Given that digital information and communication technologies have the potential to provide access to employment, education, income, health services, participation, protection, and safety, among others (ICT4D), the natural affinity of women with these new communication tools provide women with a tangible bootstrapping opportunity to tackle social discrimination. A target of global initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 is to enhance the use of enabling technology to promote the empowerment of women.[120]

Variations by country or culture

Gender inequality is a result of the persistent discrimination of one group of people based upon gender and it manifests itself differently according to race, culture, politics, country, and economic situation. While gender discrimination happens to both men and women in individual situations, discrimination against women is more common.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, rape and violence against women and girls is used as a tool of war.[122] In Afghanistan, girls have had acid thrown in their faces for attending school.[123] Considerable focus has been given to the issue of gender inequality at the international level by organizations such as the United Nations (UN), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank, particularly in developing countries. The causes and effects of gender inequality vary geographically, as do methods for combating it.

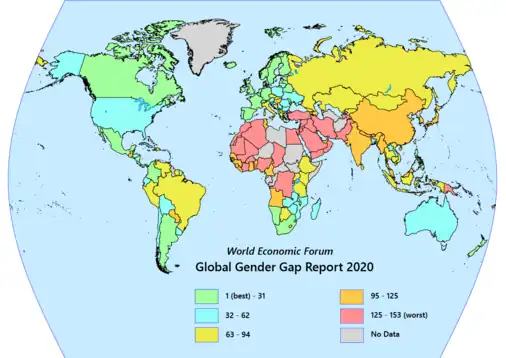

According to the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2023, it will take exactly 131 years for the gender gap to close.

Asia

One example of the continued existence of gender inequality in Asia is the "missing girls" phenomenon.[126] "Many families desire male children in order to ensure an extra source of income. In China, females are perceived as less valuable for labor and unable to provide sustenance."[127] Moreover, gender inequality is also reflected in the educational aspect of rural China. Gender inequality exists because of gender stereotypes in rural China. For example, families may consider that it is useless for girls to acquire knowledge at school because they will marry someone eventually, and their major responsibility is to take care of housework.[128]

Furthermore, the current formal education in Asia might be also a result of the historical tendencies. For instance, insufficient supply and demand for education of women reflect the development of numeracy levels throughout Asia between 1900 and 1960. Regions like South and West Asia had low numeracy levels during the early and mid-20th century. As a consequence, there were no significant gender equality trends. East Asia in its turn was characterized by a high numeracy level and gender equality. The success of this region is related to the higher education and hence higher participation rate of females in the economic life of the region.[129]

China

Gender inequality in China derives from deeply rooted Confucian beliefs about gender roles in society.[130] Despite that, gender inequality in China was relatively modest before the beginning of the Chinese economic reform in 1978. The transition period to an economic system with market elements during the 1980s though was characterized by increasing gender inequality in China.[131] On the other hand, the gender inequality was also influenced by the "One-child policy" because of the son preference.[132] Nowadays women still face discrimination in China, despite the existence of state programs[133] According to the United Nations Development Program, China was ranked 39 out of 162 countries on the Gender Inequality Index in 2018,[134] while it was ranked 91 out of 187 in 2014.[135] According to the World Economic Forum's global gender gap index, China's gap has widened and its rank has dropped to 106 out of 153 countries in 2020.[136] It ranked last in terms of health and survival.[136] According to Human Rights Watch, job discrimination remains a significant issue as 11% of postings specify a preference or requirement of men.[137] In fact, Chinese women are often asked whether they expect to have children during interview as it is considered an obstacle to the job application, and as women generally retire around 40, it is difficult for them to advance.[138] In addition, Chinese women earn 78.2% for every dollar paid to a man in 2019, according to a study conducted by Boss Zhipin.[138]

South Korea

Gender inequality in South Korea is derived from deeply rooted patriarchal ideologies with specifically defined gender-roles.[139] The gender-based stereotypes are often unchallenged and even encouraged by the government.[140] South Korea has the lowest rank among OECD countries in The Economist's Glass Ceiling Index, which evaluates women's higher education, number of women in managerial positions and in parliament.[140] The gap has improved in healthcare and education, but it is still prevalent in the economy and politics.[141] In fact, out of 36 OECD countries, South Korea ranked 30 for women's employment in 2018.[139] Victims of gender-based discrimination struggle to make a case and get justice as it is hard to prove gender discrimination and sometimes do not complain because they are afraid of the repercussions.[139] The existing directives against gender discrimination are not effective because the law is weakly enforced and corporations do not comply.[142] The inequality is even stronger in politics, with women holding 17% of the seats in the parliament.[139]

Cambodia

A Cambodian said, "Men are gold, women are white cloth", emphasizing that women had a lower value and importance compared to men.[43] In Cambodia, approximately 15% (485,000 hectares) of land was owned by women.[143] In Asian culture, there is a stereotype that women usually have lower status than men because males carry on the family name and hold the responsibilities to take care of the family. Females have a less important role, mainly to carry out domestic chores, and taking care of husbands and children.[144] Women are also the main victims of poverty as they have little or no access to education, low pay and low chances owning assets such as lands, homes or even basic items.[43]

In Cambodia, the Ministry of Women's Affairs (MoWA) was formed in 1998 with the role of improving women's overall power and status in the country.[145]

India

India ranking remains low in gender equality measures by the World Economic Forum, although the rank has been improving in recent years.[146][147] When broken down into components that contribute the rank, India performs well on political empowerment, but is scored near the bottom with China on sex-selective abortion. India also scores poorly on overall female to male literacy and health rankings. India with a 2013 ranking of 101 out of 136 countries had an overall score of 0.6551, while Iceland, the nation that topped the list, had an overall score of 0.8731 (no gender gap would yield a score of 1.0).[148] Gender inequalities impact India's sex ratio, women's health over their lifetimes, their educational attainment, and economic conditions. It is a multifaceted issue that concerns men and women alike.

The labor force participation rate of women was 80.7% in 2013.[149] Nancy Lockwood of the Society for Human Resource Management, the world's largest human resources association with members in 140 countries, in a 2009 report wrote that female labor participation is lower than men, but has been rapidly increasing since the 1990s. Out of India's 397 million workers in 2001, 124 million were women, states Lockwood.[150]

India is on target to meet its Millennium Development Goal of gender parity in education before 2016.[151] UNICEF's measures of attendance rate and Gender Equality in Education Index (GEEI) attempt to capture the quality of education.[152] Despite some gains, India needs to triple its rate of improvement to reach GEEI score of 95% by 2015 under the Millennium Development Goals. A 1998 report stated that rural India girls continue to be less educated than the boys.[153]

Africa

Although African nations have made considerable strides towards improving gender parity, the World Economic Forum's 2018 Global Gender Gap Index reported that sub-Saharan African and North African countries have only bridged 66% and 60% of their gender inequality.[154] Women face considerable barriers to attending equal status to men in terms of property ownership, gainful employment, political power, credit, education, and health outcomes.[155] In addition, women are disproportionately affected by poverty and HIV/AIDs because of their lack of access to resources and cultural influences.[156] Other key issues are adolescent births, maternal mortality, gender-based violence, child marriage, and female genital mutilation.[157] It's estimated that 50% of adolescent childbirths and 66% of all maternal deaths occurred in sub-Saharan African nations.[157] Women have few rights and legal protections which have led to the highest numbers of child marriage and female genital mutilation than any other continent.[157] Furthermore, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Egypt, Lesotho, Mali, and Niger do not have any legal protections for gender-based domestic violence.[157] Religion contributes to the gender inequality experienced by women in Africa. For example, religious norms in Nigeria limit women's ability to hold leadership roles and place blame on women who seek traditionally "male" roles[158]

Europe

The Global Gender Gap Report put out by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2013 ranks nations on a scale of 0 to 1, with a score of 1.0 indicating full gender equality. A nation with 35 women and 65 men in political office would get a score of 0.538 as the WEF is measuring the gap between the two figures and not the actual percentage of women in a given category. While Europe holds the top four spots for gender equality, with Iceland, Finland, Norway and Sweden ranking first through fourth respectively, it also contains two nations ranked in the bottom 30 countries, Albania at 108 and Turkey at 120. The Nordic Countries, for several years, have been at the forefront of bridging the gap in gender inequality. Every Nordic country, aside from Denmark which is at 0.778, has reached above a 0.800 score. In contrast to the Nordic nations, the countries of Albania and Turkey continue to struggle with gender inequality. Albania and Turkey failed to break the top 100 nations in two of four and three of four factors, respectively.[146]

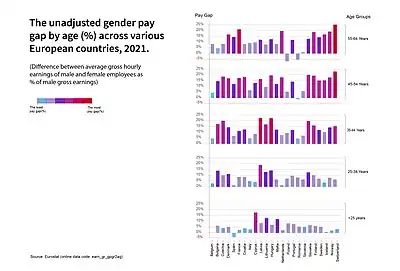

Gender is also an important aspect of economic inequality. Because women continue to hold lower-paying jobs, they earn 13% less than men on average across the European Union. According to European Quality of Life Survey and European Working Conditions Survey data, women in the European Union work more hours but for less pay. Adult men (including the retired) work an average of 23 hours per week, compared to 15 hours for women.[159]

The surveys found that while men spend up to 14 hours per week doing unpaid housework and caring for children and other family members, women spend up to 28 hours per week doing the same unpaid tasks. Women work up to six hours longer than men. If all unpaid work done by men and women at the EU median wage were to be valued, it would be worth nearly €6 trillion, or 40% of European gross domestic product.[159]

Western Europe

Western Europe, a region most often described as comprising the non-communist members of post-WWII Europe,[160] has, for the most part been doing well in eliminating the gender gap. Western Europe holds 12 of the top 20 spots on the Global Gender Gap Report for overall score. While remaining mostly in the top 50 nations, four Western European nations fall below that benchmark. Portugal is just outside of the top 50 at number 51 with score of 0.706 while Italy (71), Greece (81) and Malta (84) received scores of 0.689, 0.678 and 0.676, respectively.[146]

According to the United Nations, 21 EU's member states are in the top 30 in the world in terms of gender equality.[161] However, since 2005, the European Union has slowly improved its gender equality score according to the European Institute for Gender Equality.[162] The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights has raised gender inequality as one of the main human rights problems the European countries are facing and acknowledged the slow progress in bridging gender pay gap and addressing discrimination at work.[163] According to the European Institute for Gender Equality, the EU seems to be the closest to gender equality in the health and money domains but has a more worrying score in the domain of power.[162] As acknowledged by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, the EU is only slowly progressing when it comes to tackling women's underrepresentation in political decision-making.[163] The progress towards gender equality is uneven between member states. In fact, while Sweden and Denmark appear to be the most gender-equal societies, Greece and Hungary are far from it.[162] Italy and Cyprus are the states which improved the most.[162]

Eastern Europe

A large portion of Eastern Europe, a region most often described as the former communist members of post-WWII Europe,[160] resides between 40th and 100th place in the Global Gender Gap Report. A few outlier countries include Lithuania, which jumped nine places (37th to 28th) from 2011 to 2013, Latvia, which has held the 12th spot for two consecutive years, Albania and Turkey.[146]

Russia

According to United Nations Development Programme, Russia's gender inequality index is 0.255, ranking it 54 out of 162 countries in 2018. Women hold 16.1% of parliamentary seats and 96.3% have reached at least a secondary level of education.[164] Researchers calculate the loss to the annual budget due to gender segregation to be roughly 40–50%.[165] Although women hold prominent positions in Russia's government, traditional gender roles are still prevalent, and there is room for improvement when dealing with gender pay gap, domestic violence and sexual harassment.[166]

Turkey

According to the 2020 Gender Decoupling Index, which was created by the World Economic Forum with data on education, participation in the economy, political representation and health, Turkey is 130th out of 153 countries. in line. In other words, Turkey is the country with the highest gender Decoupling after 23 countries, including sharia-governed countries such as Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and undeveloped African countries such as Mali, Togo and Gambia.According to TurkStat data, 57% of women in Turkey are happy. The happiness rate of men is at the level of 47.6%.The labor force participation rate of women in Turkey refers to the place of women in working life, this rate is 36.2% in Turkey; the OECD average is 63.6%. Turkey is one of the few countries not only among the OECD countries of which it is a member, but also in the whole world, where the participation rate of women in the labor force is the lowest. Dec. According to the Human Development Report of the United Nations Development Program dated 2016, the labor force participation rate of women is 49.6% on average in the world and is significantly higher than that of Turkey.It shows that female unemployment in Turkey (14%) is higher than the OECD average (9.8%). In other words, there is a serious danger of protection for women in Turkey.The unequal position of women in working life is also reflected in economic income inequality. Women's share of gross national income is lower than that of men in all countries. But gender income inequality in Turkey is higher than the inequality seen in the OECD and world averages. Gross national income per capita for women in Turkey is 39.3% of that for men; the OECD average is 59.6%, and the world average is 55.5%.[167]

United States

The World Economic Forum measures gender equity through a series of economic, educational, and political benchmarks. It has ranked the United States as 19th (up from 31st in 2009) in terms of achieving gender equity.[168] The US Department of Labor has indicated that in 2009, "the median weekly earnings of women who were full-time wage and salary workers was ... 80 percent of men's".[169] The Department of Justice found that in 2009, "the percentage of female victims (26%) of intimate partner violence was about 5 times that of male victims (5%)".[170] As of 2019, the average number of women killed by an intimate partner each day has gone up from three to around four.[116] The United States ranks 41st in a ranking of 184 countries on maternal deaths during pregnancy and childbirth, below all other industrialized nations and a number of developing countries,[171] and women are just 20% of members of the United States Congress.[168] Economically, women are significantly underrepresented in prestigious and high paying occupations like company ownership and CEO roles, where they account for just 5.5% of the latter.[172] Women are around 15% of self-made millionaires and 11.8% of billionaires.[173][174]

Political affiliations and behaviors

Existing research on the topic of gender/sex and politics has found differences in political affiliation, beliefs, and voting behavior between men and women, although these differences vary across cultures. Gender is omnipresent in every culture, and while there are many factors to consider when labeling people "Democrat" or "Republican"—such as race and religion—gender is especially prominent in politics.[175][176] Studying gender and political behavior poses challenges, as it can be difficult to determine if men and women actually differ in substantial ways in their political views and voting behavior, or if biases and stereotypes about gender cause people to make assumptions.[177] However, trends in voting behavior among men and women have been proven through research.

Research shows that women in postindustrial countries like the United States, Canada, and Germany primarily identified as conservative before the 1960s; however, as time has progressed and new waves of feminism have occurred, women have become more left-wing due to shared beliefs and values between women and parties more on the left.[178] Women in these countries typically oppose war and the death penalty, favor gun control, support environment protection, and are more supportive of programs that help people of lower socioeconomic statuses.[175] Voting behaviors of men have not experienced as drastic of a shift over the last fifty years as women in their voting behavior and political affiliations. These behaviors tend to consistently be more conservative than women overall.[178] These trends change with every generation, and factors such as culture, race, and religion also must be considered when discussing political affiliation. These factors make the connection between gender and political affiliation complex due to intersectionality.[179]

Candidate gender also plays a role in voting behavior. Women candidates are far more likely than male candidates to be scrutinized and have their competence questioned by both men and women when they are seeking information on candidates in the beginning stages of election campaigns.[177] Democrat male voters tend to seek more information about female Democrat candidates over male Democrat candidates. Female Republican voters tend to seek more information about female Republican candidates.[177] For this reason, female candidates in either party typically need to work harder to prove themselves competent more than their male counterparts.[177]

Challenges to women in politics

Overall, politics in the United States is dominated by men, which can pose many challenges to women who decide to enter the political sphere. As the number of women participants in politics continue to increase around the world, the gender of female candidates serves as both a benefit and a hindrance within their campaign themes and advertising practices.[180] The overarching challenge seems to be that—no matter their actions—women are unable to win in the political sphere as different standards are used to judge them when compared to their male counterparts.[181]

One area in particular that exemplifies varying perceptions between male and female candidates is the way female candidates decide to dress and how their choice is evaluated. When women decide to dress more masculine, they are perceived as being "conspicuous". When they decide to dress more feminine, they are perceived as "deficient".[182] At the same time, however, women in politics are generally expected to adhere to the masculine standard, thereby validating the idea that gender is binary and that power is associated with masculinity.[183] As illustrated by the points above, these simultaneous, mixed messages create a "double-bind" for women. Some scholars go on to claim that this masculine standard represents symbolic violence against women in politics.[182]

Political knowledge is a second area where male and female candidates are evaluated differently and where political science research has consistently shown women with a lower level of knowledge than their male counterparts.[184] One reason for this finding is the argument that there are different areas of political knowledge that different groups consider.[185] Due to this line of thought, scholars are advocating the replacement of traditional political knowledge with gender-relevant political knowledge because women are not as politically disadvantaged as it may appear.[184]

A third area that affects women's engagement in politics is their low level of political interest and perception of politics as a "men's game".[186] Despite female candidates' political contributions being equal to that of male candidates, research has shown that women perceive more barriers to office in the form of rigorous campaigns, less overall recruitment, inability to balance office and family commitments, hesitancy to enter competitive environments, and a general lack of belief in their own merit and competence.[187] Male candidates are evaluated most heavily on their achievements, while female candidates are evaluated on their appearance, voice, verbal dexterity, and facial features in addition to their achievements.[182]

Steps needed for change

Several forms of action have been taken to combat institutionalized sexism. People are beginning to speak up or "talk back" in a constructive way to expose gender inequality in politics, as well as gender inequality and under-representation in other institutions.[188] Researchers who have delved into the topic of institutionalized sexism in politics have introduced the term "undoing gender". This term focuses on education and an overarching understanding of gender by encouraging "social interactions that reduce gender difference".[183] Some feminists argue that "undoing gender" is problematic because it is context-dependent and may actually reinforce gender. For this reason, researchers suggest "doing gender differently" by dismantling gender norms and expectations in politics, but this can also depend on culture and level of government (e.g. local versus federal).[183]

Another key to combating institutionalized sexism in politics is to diffuse gender norms through "gender-balanced decision-making", particularly at the international level, which "establishes expectations about appropriate levels of women in decision-making positions."[189] In conjunction with this solution, scholars have started placing emphasis on "the value of the individual and the importance of capturing individual experience". This is done throughout a candidate's political career—whether that candidate is male or female—instead of the collective male or female candidate experience.[190] Five recommended areas of further study for examining the role of gender in U.S. political participation are (1) realizing the "intersection between gender and perceptions"; (2) investigating the influence of "local electoral politics"; (3) examining "gender socialization"; (4) discerning the connection "between gender and political conservatism"; and (5) recognizing the influence of female political role models in recent years.[191] Due to the fact that gender is intricately entwined in every societal institution, gender in politics can only change once gender norms in other institutions change, as well.

See also

- Affirmative action

- Kenneth and Mamie Clark

- Coloniality of gender

- Discrimination

- Equal pay for women

- Feminism

- Feminization of poverty

- Gender and education

- Gender and suicide

- Gender differences

- Gender equality

- Gender inequality in Australia

- Gender inequality in Thailand

- Gender inequality in Bangladesh

- Gender polarization

- Girl Effect

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Honorary male

- Intra-household bargaining

- Kiva (organization)

- Marginalization

- Masculism

- Men's rights movement

- Microinequity

- Obedient Wives Club

- Paycheck Fairness Act (in the US)

- Polygamy

- Sex and psychology

- Sex segregation

- Sexism

- Sexual dimorphism

- Shared earning/shared parenting marriage (also known as peer marriage)

- Shared parenting (such as after divorce)

- Skin gap

- Socialization

- Special measures for gender equality in the United Nations

- Transgender inequality

- Women's rights

- World Bank

References

- DEMIRGOZ BAL, Meltem. "TOPLUMSAL CİNSİYET EŞİTSİZLİĞİNE GENEL BAKIŞ".

- Wood, Julia. Gendered Lives. 6th. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2005.

- Maughan RJ, Watson JS, Weir J (1983). "Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle". The Journal of Physiology. 338 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014658. PMC 1197179. PMID 6875963.

- Frontera, WR; Hughes, VA; Lutz, KJ; Evans, WJ (1991). "A cross-sectional study of muscle strength and mass in 45- to 78-yr-old men and women". J Appl Physiol. 71 (2): 644–50. doi:10.1152/jappl.1991.71.2.644. PMID 1938738.

- Samaras, Thomas (2007). Human body size and the laws of scaling. New York: Nova Science. pp. 33–61. ISBN 978-1-60021-408-0.

- "Life expectancy at birth, Country Comparison to the World". CIA World Factbook. US Central Intelligence Agency. n.d. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- Alfred Glucksman (1981). Sexual Dimorphism in Human and Mammalian Biology and Pathology. Academic Press. pp. 66–75. ISBN 978-0-12-286960-0. OCLC 7831448.

- Puts, David A. (2010). "Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans". Evolution and Human Behavior. 31 (3): 157–175. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.005.

- Simerly, Richard B. (1 February 2005). "Wired on hormones: endocrine regulation of hypothalamic development". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 15 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.013. ISSN 0959-4388. PMID 15721748. S2CID 24944473.

- Reinisch, June Machover; Ziemba-Davis, Mary; Sanders, Stephanie A. (1 January 1991). "Hormonal contributions to sexually dimorphic behavioral development in humans". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 16 (1–3): 213–278. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(91)90080-D. PMID 1961841. S2CID 44814972.

- Colom, Roberto; Juan-Espinosa, Manuel; Abad, Francisco; García, Luís F (February 2000). "Negligible Sex Differences in General Intelligence". Intelligence. 28 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00035-5.

- Byrnes, James P.; Miller, David C.; Schafer, William D. (1999). "Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 125 (3): 367–383. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367.

- Carlson, N. 'Hormonal Control of Aggressive Behavior' Chapter 11 in [Physiology of Behavior],2013, Pearson Education Inc.

- Card, Noel A.; Stucky, Brian D.; Sawalani, Gita M.; Little, Todd D. (1 October 2008). "Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment". Child Development. 79 (5): 1185–1229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. ISSN 1467-8624. PMID 18826521. S2CID 7942628.

- Christov-Moore, Leonardo; Simpson, Elizabeth A.; Coudé, Gino; Grigaityte, Kristina; Iacoboni, Marco; Ferrari, Pier Francesco (1 October 2014). "Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 46 (4): 604–627. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001. ISSN 1873-7528. PMC 5110041. PMID 25236781.

- Celec, Peter; Ostatníková, Daniela; Hodosy, Július (17 February 2015). "On the effects of testosterone on brain behavioral functions". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00012. ISSN 1662-4548. PMC 4330791. PMID 25741229.

- Eliot, Lise. Pink Brain, Blue Brain.

- Cordier, B (2012). "Gender, betwixt biology and society". European Journal of Sexology and Sexual Health.

- Brescoll, V (2013). "The effects of system-justifying motives on endorsement of essentialist explanations for gender differences". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 105 (6): 891–908. doi:10.1037/a0034701. PMID 24295379. S2CID 3333149.

- Hyde, J (2005). "The gender similarities hypothesis". American Psychologist. 60 (6): 581–592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. PMID 16173891.

- CONSAD Research Corporation, An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013

- Patten, Eileen (14 April 2015). "On Equal Pay Day, key facts about the gender pay gap". Pew Research Center.

- Francine D. Blau; Lawrence M. Kahn (2007). "The Gender Pay Gap – Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?" (PDF). Academy of Management Perspectives. 21 (1): 7–23. doi:10.5465/AMP.2007.24286161. S2CID 152531847.

- European Commission. Tackling the gender pay gap in the European Union (PDF). ISBN 978-92-79-36068-8.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - "What are the causes? - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- O'Brien, Sara Ashley (14 April 2015). "78 cents on the dollar: The facts about the gender wage gap". CNN Money. New York. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Jackson, Brooks (22 June 2012). "Obama's 77-Cent Exaggeration". FactCheck.org.

- "An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women" (PDF). US Department of Labor; CONSAD Research Corp. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Graduating to a Pay Gap – The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation (PDF)

- Sommers, Christina H (23 January 2014). "Wage Gap Myth Exposed — By Feminists". Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Goldin, C., (2014). A pollution theory of discrimination: male and female differences in occupations and earnings. In L. Platt, Boustan, C. Frydman, and R. A. Margo, eds. Human capital in history: The American record. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 313-348.

- Massey, Douglas. "Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System". NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2007.

- Preston, Jo Anne (1 January 1999). "Occupational gender segregation Trends and explanations". The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 39 (5): 611–624. doi:10.1016/S1062-9769(99)00029-0. ISSN 1062-9769.

- Cotter, David, Joan Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman. The American People Census 2000: Gender Inequality at Work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

- Hurst, Charles, E. Social Inequality. 6th. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2007.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of Women's Earnings in 2009. Report 1025, June 2010.

- CONSAD research corp. (12 January 2009). "An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Cotter, David, Joan Hermsen, Seth Ovadia and Reeve Vanneman. "The Glass Ceiling Effect". Social Forces. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Burstein, Paul. Equal Employment Opportunity: Labor Market Discrimination and Public Policy. Edison, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 1994.

- Sherri Grasmuck and Rosario Espinal. "Market Success or Female Autonomy?" Sage Publications, Inc, 2000.

- Census

- Women 'earn less than men across the globe' Archived 26 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Vedior, 4 March 2008

- "What's a woman worth?: wages and democracy in Cambodia". openDemocracy. 1 February 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. "On The Pill: Changing the course of women's education". The Milken Institute Review, Second Quarter 2001: p3.

- Goldin, Claudia; Katz, Lawrence F. (2002). "The Power Of The Pill: Contraceptives And Women's Career And Marriage Decisions". Journal of Political Economy. 110 (4): 731. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.473.6514. doi:10.1086/340778. S2CID 221286686.

- Catalyst. "Targeting Inequity: The Gender Gap in U.S. Corporate Leadership" (PDF).

- Myers, Robert M., and Amy L. Griffin. “The Geography of Gender Inequality in International Higher Education.” Journal of studies in international education 23.4 (2019): 429–450. Web.

- Goldin, Claudia (2006). "The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women's Employment, Education, And Family" (PDF). American Economic Review. 96 (2): 13. doi:10.1257/000282806777212350. S2CID 245351493.

- Moss-Racusin; et al. (2012). "Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students". PNAS. 109 (41): 16474–16479. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10916474M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109. PMC 3478626. PMID 22988126.

- Williams, Wendy; Stephen, Ceci (28 April 2015). "National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track". PNAS. 112 (17): 5360–5365. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.5360W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418878112. PMC 4418903. PMID 25870272.

- What Lies Behind Gender Inequality in Education? 2015, s.n., S.l.

- Faber, Jorge (March 2017). "A call to promote gender equality in dentistry". Journal of the World Federation of Orthodontists. 6 (1): 1. doi:10.1016/j.ejwf.2017.03.001.

- Office for National Statistics. 2016. UK Labour Market Employment by Occupation. Quarter 2 figures, 2016. Accessed: www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uk/labourmarket/jan2017