East African campaign (World War I)

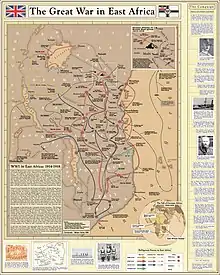

The East African campaign in World War I was a series of battles and guerrilla actions, which started in German East Africa (GEA) and spread to portions of Mozambique, Rhodesia, British East Africa, the Uganda, and the Belgian Congo. The campaign all but ended in German East Africa in November 1917 when the Germans entered Mozambique and continued the campaign living off Portuguese supplies.[14]

| East African campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the African theatre of World War I | |||||||||

An Askari company ready to march in German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

British Empire Initially: 2 battalions[1] 12,000–20,000 soldiers Total: 250,000 soldiers[2] 600,000 porters[3] |

Regulars (Schutztruppe) Initially: 2,700[lower-alpha 1] Maximum: 18,000[lower-alpha 2] 1918: 1,283[lower-alpha 3] Total: 22,000[lower-alpha 4] Irregulars (Ruga-Ruga) 12,000+[7][lower-alpha 5] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

|

365,000 civilians died in war-related famines.[lower-alpha 9]

| |||||||||

The strategy of the German colonial forces, led by Lieutenant Colonel (later Major General) Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, was to divert Allied forces from the Western Front to Africa. His strategy achieved only mixed results after 1916 when he was driven out of German East Africa. The campaign in Africa consumed considerable amounts of money and war material that could have gone to other fronts.[2][15]

The Germans in East Africa fought for the whole of the war, receiving word of the armistice on 14 November 1918 at 07:30 hours. Both sides waited for confirmation, with the Germans formally surrendering on 25 November. GEA became two League of Nations Class B Mandates, Tanganyika Territory of the United Kingdom and Ruanda-Urundi of Belgium, while the Kionga Triangle was ceded to Portugal.

Background

German East Africa

German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) was colonized by the Germans in 1885. The territory itself spanned 384,180 square miles (995,000 km2) and covered the areas of modern-day Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania.[16] The colony's indigenous population numbered seven and a half million and was governed by just 5,300 Europeans. Although the colonial regime was relatively secure, the colony had recently been shaken by the Maji Maji Rebellion of 1904–1905. The German colonial administration could call on a military Schutztruppe ("Protection force") of 260 Europeans and 2,470 Africans, in addition to 2,700 white settlers who were part of the reservist Landsturm, as well as a small paramilitary Gendarmerie.[16]

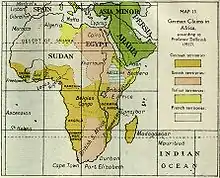

The outbreak of World War I in Europe led to the increased popularity of German colonial expansion and the creation of a Deutsch-Mittelafrika ("German Central Africa") which would parallel a resurgent German Empire in Europe. Mittelafrika effectively involved the annexation of territory, mostly occupied by the Belgian Congo, in order to link the existing German colonies in East, South-west and West Africa. The territory would dominate central Africa and would make Germany by far the most powerful colonial power on the African continent.[17] Nevertheless, the German colonial military in Africa was weak, poorly equipped and widely dispersed. Although better trained and more experienced than their opponents, many of the German soldiers were reliant on weapons like the Model 1871 rifle which used obsolete black powder.[18] At the same time the militaries of the Allied powers were also encountering similar problems of poor equipment and low numbers; most colonial militaries were intended to serve as local paramilitary police to suppress resistance to colonial rule and were neither equipped nor structured to fight against foreign powers.[19] Even so, the largest military concentration in the German colonial empire was in East Africa.

German strategy

The objective of the German forces in East Africa, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, was to divert Allied forces and supplies from Europe to Africa. By threatening the important British Uganda Railway, Lettow hoped to force British troops to invade East Africa, where he could fight a defensive campaign.[20] In 1912, the German government had formed a defensive strategy for East Africa in which the military would withdraw to the hinterland and fight a guerilla campaign.[21] The German colony in East Africa was a threat to the neutral Belgian Congo but the Belgian government hoped to continue its neutrality in Africa. The Force Publique was constrained to adopt a defensive strategy until 15 August 1914, when German ships on Lake Tanganyika bombarded the port of Mokolobu and then the Lukuga post a week later. Some Belgian officials viewed hostilities in East Africa as an opportunity to expand Belgian holdings in Africa; the capture of Ruanda and Urundi could increase the bargaining power of the De Broqueville government to ensure the restoration of Belgium after the war.[22] During the post-war negotiation of the Treaty of Versailles, the Colonial Minister, Jules Renkin, sought to trade Belgian territorial gains in German East Africa for the Portuguese allocation in northern Angola, to gain Belgian Congo a longer coast.[23]

Initial fighting, 1914–1915

Outbreak and early German attacks

The governors of the British and German East Africa wanted to avoid war and preferred a neutrality agreement based on the Congo Act of 1885, against the wishes of the local military commanders and their metropolitan governments. The agreement caused confusion in the opening weeks of the conflict. On 31 July, implementing contingency plans, the cruiser SMS Königsberg sailed from Dar-es-Salaam for operations against British commerce. She narrowly avoided cruisers from the Cape Squadron sent to shadow the ship and be ready to sink it.[24] On 5 August 1914, troops from the Uganda protectorate assaulted German river outposts near Lake Victoria.[25]

On the same day, the British War Cabinet ordered an Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF) to be sent to East Africa to eliminate bases for raiders.[26] On 8 August, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Astraea shelled the wireless station at Dar es Salaam, then agreed a ceasefire, on condition the town remained an open city.[27] This agreement caused discord between Vorbeck and Governor Heinrich Schnee, his nominal superior, who opposed and later ignored the agreement; it also caused the captain of Astraea to be reprimanded for exceeding his authority. Before the Battle of Tanga when the IEF attempted to land at Tanga, the Royal Navy felt obliged to give warning that they were abrogating the agreement, forfeiting surprise.[28]

In August 1914, the military and para-military forces in both colonies were mobilised, despite restrictions imposed by the two governors. The German Schutztruppe in East Africa had 260 Germans of all ranks and 2,472 Askari, equivalent to the two battalions of the King's African Rifles (KAR) in the British East African colonies.[29][1] On 7 August, German troops at Moshi were informed that the neutrality agreement was at an end and ordered to raid across the border. On 15 August, Askari in the Neu Moshi region engaged in their first offensive operation of the campaign. Taveta on the British side of Kilimanjaro fell, to two companies of Askari (300 men) with the British firing a token volley and retiring in good order.[30] The Askari detachment on Lake Tanganyika raided Belgian facilities seeking to destroy the steamer Commune and gain control of the lake. On 24 August, German troops attacked Portuguese outposts across the Rovuma, unsure of the intentions of Portugal, which was not yet a British ally, which caused a diplomatic incident which was only smoothed over with difficulty.[19]

In September, the Germans began to raid deeper into British Kenya and Uganda. German naval power on Lake Victoria was limited to Hedwig von Wissmann and Kingani a tugboat armed with one pom-pom-gun, causing minor damage and a great deal of noise. The British armed the Uganda Railway lake steamers SS William Mackinnon, SS Kavirondo, SS Winifred and SS Sybil as improvised gunboats; the tug was trapped and then scuttled by the Germans.[31] The Germans later raised Kingani, dismounted her gun and used the tug as a transport; with the tug disarmed and her "teeth removed, British command of Lake Victoria was no longer in dispute."[32]

British land and naval offensive

To solve the raiding nuisance and to capture the northern, colonised region of the German colony, the British devised a plan for a two-pronged invasion. IEF "B" of 8,000 troops in two brigades, would carry out an amphibious landing at Tanga on 2 November 1914, to capture the city and gain control the Indian Ocean terminus of the Usambara Railway. In the Kilimanjaro area, IEF "C" of 4,000 men in one brigade would advance from British East Africa on Neu-Moshi on 3 November 1914, to the western terminus of the railroad (see Battle of Kilimanjaro). After capturing Tanga, IEF "B" would rapidly move north-west, join IEF "C" and mop up the remaining German forces. Although outnumbered 8:1 at Tanga and 4:1 at Longido, the Schutztruppe under Vorbeck prevailed. In the East Africa volume of the British official history (1941), Charles Hordern described the events as one of "the most notable failures in British military history".[33]

Only two British regiments were involved in the East African campaign. The 2nd Battalion, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment arrived with the Indian Army invasion force at Tanga and after this stayed on the border between British and German East Africa. The 25th (Frontiersmen) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers was raised for service in East Africa in early 1915 and served throughout the war. In addition, white contingents were supplied by Rhodesia in 1914-15, the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment, Nyasaland and South Africa including the South African Expeditionary Force which arrived in February 1916.[34]

Königsberg of the Imperial German Navy was in the Indian Ocean when war was declared. In the Battle of Zanzibar, Königsberg sank the old protected cruiser HMS Pegasus in Zanzibar harbour and then retired into the Rufiji River delta.[35] After being cornered by warships of the British Cape Squadron, including an old pre-dreadnought battleship, two shallow-draught monitors with 6 in (150 mm) guns were brought from England and demolished the cruiser on 11 July 1915.[36] The British salvaged and used six 4 in (100 mm) guns from Pegasus, which became known as the Peggy guns; the crew of Königsberg and the 4.1 in (100 mm) main battery guns were taken over by the Schutztruppe and were used until the end of hostilities.[37]

Lake Tanganyika expedition

The Germans had controlled the lake since the outbreak of the war, with three armed steamers and two unarmed motor boats. In 1915, two British motorboats, HMS Mimi and Toutou each armed with a 3-pounder and a Maxim gun, were transported 3,000 mi (4,800 km) by land to the British shore of Lake Tanganyika. They captured the German ship Kingani on 26 December, renaming it HMS Fifi and with two Belgian ships under the command of Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson, attacked and sank the German ship Hedwig von Wissmann. The Graf von Götzen and the Wami, an unarmed motor boat, became the only German ships left on the lake. In February 1916, the Wami was intercepted and run ashore by the crew and burned.[38] Lettow-Vorbeck then had its Königsberg gun removed and sent by rail to the main fighting front.[39] The ship was scuttled in mid-July after a seaplane bombing attack by the Belgians on Kigoma and before advancing Belgian colonial troops could capture it; Wami was later re-floated and used by the British.[40][lower-alpha 10]

Allied offensives, 1916–1917

British Empire reinforcements, 1916

General Horace Smith-Dorrien was assigned with orders to find and fight the Schutztruppe but he contracted pneumonia during the voyage to South Africa, which prevented him from taking command. In 1916, General Jan Smuts was given the task of defeating Lettow-Vorbeck.[42] Smuts had a large army (for the area), some 13,000 South Africans including Boers, British, Rhodesians and 7,000 Indian and African troops, a ration strength of 73,300 men.[lower-alpha 11] There was a Belgian force and a larger but ineffective group of Portuguese military units based in Mozambique. A large Carrier Corps composed of African porters under British command, carried supplies into the interior. Despite the Allied nature of the effort, it was a South African operation of the British Empire. During the previous year, Lettow-Vorbeck had also gained personnel and his army was now 13,800 strong.[43]

Smuts attacked from several directions, the main attack coming from British East Africa (Kenya) in the north, while substantial forces from the Belgian Congo advanced from the west in two columns, crossing Lake Victoria on the British troop ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga and into the Rift Valley. Another contingent advanced over Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) from the south-east. All these forces failed to capture Lettow-Vorbeck and they all suffered from disease along the march. The 9th South African Infantry, started with 1,135 men in February, and by October its strength was reduced to 116 fit troops, with little fighting. The Germans nearly always retreated from the larger British troop concentrations and by September 1916, the German Central Railway from the coast at Dar es Salaam to Ujiji was fully under British control.[44]

With Lettow-Vorbeck confined to the southern part of German East Africa, Smuts began to withdraw the South African, Rhodesian and Indian troops and replace them with Askari of the King's African Rifles (KAR), which by November 1918 had 35,424 men. By the start of 1917, more than half the British Army in the theatre was composed of Africans and by the end of the war, it was nearly all-African. Smuts left the area in January 1917, to join the Imperial War Cabinet at London.[45]

Belgian offensives, 1916–17

The British conscripted 120,000 carriers to move Belgian supplies and equipment to Kivu (in the east of the Belgian Congo) between late 1915 and early 1916. The lines of communication in the Congo required c. 260,000 carriers, who were barred by the Belgian government from crossing into German East Africa; Belgian troops were expected to live off the land. To avoid the plundering of civilians, loss of food stocks and risk of famine, with many farmers already conscripted and moved away from their land, the British set up the Congo Carrier Section of the East India Transport Corps (Carbel) with 7,238 carriers, conscripted from Ugandan civilians and assembled at Mbarara in April 1916. The Force Publique, started its campaign on 18 April 1916 under the command of General Charles Tombeur, Colonel Philippe Molitor and Colonel Frederik-Valdemar Olsen and captured Kigali in Rwanda on 6 May.[46]

The German Askari in Burundi were forced to retreat by the numerical superiority of the Force Publique and by 17 June, Burundi and Rwanda were occupied. The Force Publique and the British Lake Force then started a thrust to capture Tabora, an administrative base in central German East Africa. Three columns took Biharamuro, Mwanza, Karema, Kigoma and Ujiji. At the Battle of Tabora on 19 September, the Germans were defeated and the village occupied.[47] During the march, Carbel lost 1,191 carriers died or missing presumed dead, a rate of 1:7, which occurred despite the presence of two doctors and adequate medical supplies.[48] To prevent Belgian claims on German territory in a post-war settlement, Smuts ordered their forces to return to the Congo, leaving them as occupiers only in Rwanda and Burundi. The British were obliged to recall Belgian troops in 1917 and the two allies coordinated campaign plans.[49]

British offensive, 1917

Major-General Arthur Hoskins (KAR), formerly the commander of the 1st East Africa Division, took over command of the campaign. After four months spent reorganising the lines of communication, he was then replaced by South African Major-General Jacob van Deventer. Deventer began an offensive in July 1917, which by early autumn had pushed the Germans 100 mi (160 km) to the south.[50] From 15–19 October 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck fought a costly battle at Mahiwa, with 519 German casualties and 2,700 British losses in the Nigerian brigade.[51] After the news of the battle reached Germany, Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to Generalmajor.[52][lower-alpha 12]

German offensives, 1917–18

Portuguese Mozambique

British units forced the Schutztruppe south and on 23 November, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed into Mozambique to plunder supplies from Portuguese garrisons. Lettow-Vorbeck divided his force into three groups on the march; a detachment of 1,000 men under Hauptmann Theodor Tafel ran out of food and ammunition and was forced to surrender before reaching Mozambique. Lettow and Tafel were unaware they were only one day's march apart. The Germans fought the Battle of Ngomano in which the Portuguese garrison was routed, then marched through Mozambique in caravans of troops, carriers, wives and children for nine months but were unable to gain much strength.[54] In Mozambique, the Schutztruppe won a number of important victories which allowed it to remain active but also came close to destruction during the Battle of Lioma and Battle of Pere Hills.[55][56]

Northern Rhodesia

The Germans returned to German East Africa and crossed into Rhodesia in August 1918. from early October, news that could be gleaned went from bad to worse. It was rumoured that Hindenburg was dead and that the Allies were about to impose an armistice on Germany and morale amongst the Germans plunged and desertions by carriers increased. On 9 November the German force reached Kasama whose district officer, Hector Croad, had evacuated the town on hearing of the German approach and stripped it of ammunition. The Germans pursued Croad who had lodged the supplies in a rubber factory on the opposite side of the Chambezi River. The Germans began probing attacks on the factory on 12 November, as Lettow-Vorbeck and his column arrived. The Germans captured the factory after a four-hour engagement and the British melted away to the west. A British dispatch rider fell into German hands who told the Germans of the Armistice of 11 November 1918. The information arrived in time to forestall another attack on the rubber factory and Croad met Lettow-Vorbeck, who found it difficult to believe that Germany had lost the war and impossible to accept that the Kaiser had fled to Holland and that Germany had become a republic.[57]

German surrender

The terms of the armistice were a great shock to the Germans but at 11:00 a.m. on 25 November 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck offered his surrender to the British at Abercorn, two weeks after the signing of the armistice in Europe. Brigadier-General William Edwards, Lettow-Vorbeck, Walter Spangenburg, and Captain Anderson, Edwards declining Lettow-Vorbeck's sword. The governor of German East Africa, Heinrich Schnee did not sign the surrender to signify that Germans renounced claims to the colony. Article XVII of the armistice required the evacuation of the German forces from East Africa but the War Office interpreted this as to need unconditional surrender and disarmament, which was carried off "by a judicious mixture of firmness and bluff". Lettow-Vorbeck smelt a rat but was unable to confirm his suspicions with Berlin and gave way under protest.[57][lower-alpha 13] The campaign cost the British c. £12 billion at 2007 prices.[58]

Aftermath

Analysis

Nearly 400,000 Allied soldiers, sailors, merchant marine crews, builders, bureaucrats and support personnel participated in the East Africa campaign. They were assisted in the field by 600,000 African bearers. The Allies employed nearly one million people in their fruitless pursuit of Lettow-Vorbeck and his small force.[3] Lettow-Vorbeck was cut off and could entertain no hope of victory. His strategy was to keep as many British forces diverted to his pursuit for as long as possible and to make the British expend the largest amount of resources in men, shipping and supplies against him. Although diverting in excess of 200,000 Indian and South African troops against his forces and garrison German East Africa in his wake, he could divert no more Allied manpower from the European theatre after 1916. While some shipping was diverted to the African theatre, it was not enough to inflict significant difficulties on the Allied navies.[14]

Soon after the end of World War I, the narrative about the East African campaign became the subject of mythologization and distortions.[59] Upon returning home, the Schutztruppe veterans, most importantly Lettow-Vorbeck, were treated as "heroes" by Germans who "refused to accept the reality of defeat in the field". Lettow-Vorbeck supported the narrative that his force had remained undefeated. By the time of his surrender, he insisted on signing the surrender documents on several conditions, including that his force was recorded as having stayed in the field until the conflict's end. In reality, he agreed to an unconditional surrender, albeit under protest.[60] In the years after the war, German colonial and military literature as well as the Nazi Party pushed the view that Lettow-Vorbeck had been "undefeated in the field" (German: Im Feld unbesiegt!) as part of the larger stab-in-the-back myth.[59][lower-alpha 14] In Germany, Lettow-Vorbeck and the East African campaign became the subject of songs and glorification.[59] Many Allied commanders also felt great respect for the East African Schutztruppe and Lettow-Vorbeck in particular, further enhancing their military reputation.[62]

Views about Lettow-Vorbeck's campaign vary. A large number of modern historians and other researchers have continued to describe the Germans in East Africa as undefeated by the end of the war.[63][lower-alpha 15][64][lower-alpha 16][65][lower-alpha 17][lower-alpha 18] A growing number of German historians have criticised this view since the 1990s, alongside other narratives about Lettow-Vorbeck as outdated, biased and based on post-war legends.[67]

Society and economy

The fighting in East Africa led to an export boom in British East Africa and an increase in the political influence of White Kenyans. In 1914, the Kenyan economy was in decline but because of emergency legislation giving white colonists control over black-owned land in 1915, exports rose from £3.35 million to £5.9 million by 1916. The increase in the value of exports was mostly due to products like raw cotton and tea. White control of the economy rose from 14 per cent to 70 per cent by 1919.[68]

The campaign and recruiting in Nyasaland contributed to the outbreak of the Chilembwe rebellion in January 1915, by John Chilembwe, an American-educated Baptist minister. Chilembwe was motivated by grievances against the colonial system including forced labour and racial discrimination. The revolt broke out in the evening of 23 January 1915 when rebels, incited by Chilembwe, attacked the headquarters of the A. L. Bruce Plantation at Magomero and killed three white colonists. An abortive attack on an armoury in Blantyre followed during the night. By the morning of 24 January the colonial authorities had mobilised the colonial militia and redeployed regular military units from the KAR. After a failed attack by government troops on Mbombwe on 25 January, the rebels attacked a Christian mission at Nguludi and burned it down. Mbombwe was retaken by government forces unopposed on 26 January. Many of the rebels, including Chilembwe, fled towards Portuguese Mozambique but most were captured. About forty rebels were executed in the aftermath and 300 were imprisoned; Chilembwe was shot dead by a police patrol near the border on 3 February. Although the rebellion did not achieve lasting success, it is commonly cited as a watershed in Malawian history.

Casualties

In 2001, Hew Strachan estimated that British losses in the East African campaign were 3,443 killed in action, 6,558 died of disease and c. 90,000 African porters died.[69] In 2007, Paice recorded c. 22,000 British casualties in the East African campaign, of whom 11,189 died, 9 percent of the 126,972 troops in the campaign. By 1917, the conscription of c. 1,000,000 Africans as carriers, depopulated many districts and c. 95,000 porters had died, among them 20 percent of the Carrier Corps in East Africa.[70] Of the porters who died, 45,000 were Kenyan, amounting to 13 percent of the male population. The campaign cost the British £70 million, close to the war budget set in 1914.[71][72] A Colonial Office official wrote that the East African campaign had not become a scandal only "... because the people who suffered most were the carriers - and after all, who cares about native carriers?".[73] The Belgian record of 5,000 casualties includes 2,620 soldiers killed in action or died of disease but excludes 15,650 porter deaths.[74] Portuguese casualties in Africa were 5,533 soldiers killed, 5,640 troops missing or captured and an unknown but significant number wounded.[75]

In the German colonies, no records of the number of people conscripted or casualties were kept but in Der Weltkrieg, the German official history, Ludwig Boell (1951) wrote "... of the loss of levies, carriers, and boys (sic) [we could] make no overall count due to the absence of detailed sickness records". Paice wrote of a 1989 estimate of 350,000 casualties and a death rate of 1-in-7 people. Carriers were rarely paid and food and cattle were requisitioned from civilians; a famine caused by the subsequent food shortage and poor rains in 1917 led to another 300,000 civilian deaths in German East Africa. The conscription of farm labour in British East Africa and the failure of the 1917–1918 rains, led to famine and in September the 1918 flu pandemic reached sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya and Uganda 160,000–200,000 people died, in South Africa there were 250,000–350,000 deaths and in German East Africa 10–20 percent of the population died of famine and disease; in sub-Saharan Africa, 1,500,000–2,000,000 people died in the flu epidemic.[76] Overall, the German conduct of war directly led to the death of at least 350,000 civilians in East Africa; most German colonial soldiers and officers, including Lettow-Vorbeck, never expressed remorse for these losses.[77]

Notes

- 200 Europeans and 2,500 Askari.[4]

- 3,000 Europeans and 15,000 Askari.[5]

- 115 Europeans and 1,168 Askari.[5]

- 5,000 Europeans and 17,000 Askari.[6]

- The exact number of irregulars in German service is unknown; the British War Office estimated that it was 12,000. Numbers of Ruga-Ruga in German service also tended fluctuate greatly due to the fact that they fought, left or deserted when they saw fit.[8]

- According to Clodfelter, this includes 1,290 Askari and 739 Germans (100 officers); 874 Germans were also wounded including those captured.[6]

- According to Clodfelter, 2,487 Askari and 2 Germans.[12]

- According to Clodfelter, 2,847 Germans and 4,275 Askari.[6]

- The proportions of African civilians who died of war-related causes are Kenya 30,000, Tanzania 100,000, Mozambique 50,000, Rwanda 15,000, Burundi 20,000 and Belgian Congo 150,000.[13]

- The ship is still in service as the Liemba, plying the lake under the Tanzanian flag.[41]

- The Allied force in East Africa became composed almost entirely of South African, Indian, and other colonial troops. Black South African troops were not considered for European service as a matter of policy, while all Indian units had been withdrawn from the Western Front by the end of 1915.

- In early November 1917, the German naval dirigible L.59 travelled over 4,200 mi (6,800 km) in 95 hours towards East Africa, but was recalled by the German admiralty before it arrived.[53]

- The Lettow-Vorbeck Memorial marks the spot in Zambia.[58]

- Prominent early proponents of the claim about an Allied de facto defeat in the East African campaign included Ernst Gerhard Jacob, a former colonial official and historian, Heinz-Wilhelm Bauer, NSDAP Office of Colonial Policy official, and Walther Doering, a higher-ranking member of the Reichskolonialbund.[61]

- "This essentially undefeated German campaign has ..."[63]

- "In practice, when the Armistice was declared in 1918 von Lettow-Vorbeck remained undefeated, ..."[64]

- "Upon learning of the armistice in Europe, he negotiated the surrender of his undefeated army. Lettow-Vorbeck had ..."[65]

- "Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s continual success in fighting against a combined allied force in what resembled guerrilla tactics more than open battle left his troops the only German military unit undefeated at the end of the war in 1918."[66]

Footnotes

- Miller 1974, p. 41.

- Holmes 2001, p. 359.

- Garfield 2007, p. 274.

- Contey 2002, p. 46.

- Crowson 2003, p. 87.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 416.

- Pesek (2014), p. 94.

- Pesek (2014), pp. 94–97.

- Morlang 2008, p. 91.

- Paice 2009, p. 388.

- Michels 2009, p. 117.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 415.

- Erlikman 2004, p. 88.

- Holmes 2001, p. 361.

- Strachan 2004, p. 642.

- Chappell 2005, p. 11.

- Louis 1963, p. 207.

- Anderson 2004, p. 27.

- Anderson 2004, p. 21.

- Louis 1963, pp. 207–208.

- Strachan 2003, pp. 575–576.

- Strachan 2003, p. 585.

- Strachan 2004, p. 112.

- Corbett 2009, p. 152.

- Hordern 1990, pp. 41–42.

- Hordern 1990, pp. 30–31.

- Farwell 1989, p. 122.

- Farwell 1989, p. 166.

- Farwell 1989, p. 109.

- Miller 1974, p. 43.

- Hordern 1990, pp. 28, 55.

- Miller 1974, p. 195.

- Farwell 1989, p. 178.

- "East Africa". Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Hordern 1990, p. 45.

- Hordern 1990, p. 153.

- Hordern 1990, p. 45, 162.

- Newbolt 2003, pp. 80–85.

- Miller 1974, p. 211.

- Foden 2004.

- Paice 2009, p. 230.

- Strachan 2003, p. 602.

- Strachan 2003, p. 599.

- Strachan 2003, p. 618.

- Strachan 2003, pp. 627–628.

- Strachan 2003, p. 617.

- Strachan 2003, pp. 617–619.

- Paice 2009, pp. 284–285.

- Strachan 2003, p. 630.

- Miller 1974, p. 281.

- Miller 1974, p. 287.

- Hoyt 1981, p. 175.

- Willmott 2003, p. 192.

- Miller 1974, p. 297.

- Paice (2009), pp. 379–383.

- Miller (1974), p. 318.

- Paice 2009, pp. 385–386.

- Paice 2009, p. 1.

- Schulte-Varendorff 2006, pp. 117–118.

- Paice 2009, pp. 387–389.

- Schulte-Varendorff 2006, p. 118.

- Paice 2009, pp. 387–390.

- Nasson 2014, p. 161.

- Stone 2015, p. 88.

- Tucker 2002, p. 194.

- Schneck 2008, p. 105.

- Schulte-Varendorff 2006, pp. 144–146.

- Strachan 2004, p. 115.

- Strachan 2003, pp. 641, 568.

- Paice 2009, pp. 392–393.

- Sondhaus 2011, p. 120.

- Chantrill 2016.

- Paice 2009, p. 393.

- Annuaire 1922, p. 100.

- Statistics 1920, pp. 352–357.

- Paice 2009, pp. 393–398.

- Paice 2009, p. 398.

Bibliography

Books

- Anderson, Ross (2004). The Forgotten Front: The East Africa Campaign, 1914–1918. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2344-9.

- Chappell, Mike (2005). The British Army in World War I: The Eastern Fronts. Vol. III. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-401-6.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopaedia of Casualty and other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd repr. Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Crowson, T. A. (2003). When Elephants Clash. A Critical Analysis of Major General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck in the East African Theatre of the Great War. NTIS, Springfield, VA.: Storming Media. OCLC 634605194.

- Erlikman, Vadim (2004). Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke [Population Losses in the Twentieth Century: A Handbook]. Moscow: Russkai︠a︡ panorama. ISBN 978-5-93165-107-1.

- Farwell, B. (1989). The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-30564-7.

- Foden, G. (2004). Mimi and Toutou Go Forth: The Bizarre Battle for Lake Tanganyika. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-100984-1.

- Garfield, Brian (2007). The Meinertzhagen Mystery. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-041-9.

- Hordern, C. (1990) [1941]. Military Operations East Africa: August 1914 – September 1916. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-158-9.

- Holmes, Richard (2001). The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860696-3.

- Hoyt, E. P. (1981). Guerilla: Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck and Germany's East African Empire. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-02-555210-4.

- Michels, Stefanie (2009). Schwarze Deutsche Kolonialsoldaten. Mehrdeutige Repräsentationsräume und früher Kosmopolitismus in Afrika [Black German Colonial Soldiers. Ambiguous Representational Spaces and Former Cosmopolitanism in Africa]. Histoire Transcript (Firm) (in German). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8376-1054-3.

- Miller, C. (1974). Battle for the Bundu: The First World War in East Africa. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-02-584930-3.

- Morlang, Thomas (2008). Askari und Fitafita. "Farbige" Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien [Askari and Fitafita. 'Colored' Mercenaries in the German Colonies]. Schlaglichter der Kolonialgeschichte (in German). Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-476-1.

- Newbolt, H. (2003) [1928]. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents: Naval Operations. Vol. IV (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-84342-492-5. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- Paice, E. (2009) [2007]. Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2349-1.

- Pesek, Michael (2014). "Ruga-ruga: The History of an African Profession, 1820–1918". In Berman, Nina; Mühlhahn, Klaus; Nganang, Patrice (eds.). German Colonialism Revisited: African, Asian, and Oceanic Experiences. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 85–100.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (1963). Ruanda-Urundi, 1884–1919. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 445674.

- Sondhaus, L. (2011). World War One: The Global Revolution. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73626-8.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920 (online ed.). London: War Office. 1920. OCLC 1318955. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Schulte-Varendorff, Uwe (2006). Kolonialheld für Kaiser und Führer. General Lettow-Vorbeck. Berlin: C.H. Links. ISBN 9783861534129.

- Stone, David (2015). The Kaiser's Army: The German Army in World War One. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781844862917.

- Strachan, H. (2003) [2001]. The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I (pbk. ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Strachan, H. (2004). The First World War in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925728-7.

- Tucker, Spencer (2002). The Great War, 1914-1918. Routledge. ISBN 9781134817504.

- Willmott, H. P. (2003). First World War. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4053-0029-2.

Journals

- "Annuaire statistique de la Belgique et du Congo Belge 1915–1919" [Statistics of Belgium and the Belgian Congo Annual]. Annuaire Statistique de la Belgique et du Congo Belge. Bruxelles: Institut national de statistique for Ministère des affaires économiques. 1922. ISSN 0770-2221.

- Contey, F. (2002). "Zeppelin Mission to East Africa". Aviation History. Weider History Group. XIII (1). ISSN 1076-8858.

- Nasson, Bill (2014). "More Than Just von Lettow-Vorbeck: Sub-Saharan Africa in the First World War". Geschichte und Gesellschaft. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. 40 (2). doi:10.13109/gege.2014.40.2.160. ISSN 0340-613X.

- Schneck, Peter (2008). "The New Negro from Germany". American Art. The University of Chicago Press. 22 (3): 102–111. doi:10.1086/595810. ISSN 1073-9300. S2CID 191450795.

Websites

- Chantrill, C. (29 November 2016). "Spending / Pie Chart 1914". ukpublicspending co uk. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

Further reading

Books

- Abbott, P. (2002). Armies in East Africa 1914–1918. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-489-4.

- Calvert, A. F. (1915). South-West Africa During the German Occupation, 1884–1914. London: T. W. Laurie. OCLC 7534413. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Calvert, A. F. (1917). German East Africa. London: T. W. Laurie. OCLC 1088504. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Chase, Jonathon (2014). Between: A Story of Africa: A Novel. Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press. ISBN 978-1-4908-1451-3.

- Clifford, H. C. (2013) [1920]. The Gold Coast Regiment in the East African Campaign (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-78331-012-8. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Dane, E. (1919). British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific, 1914–1918. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 2460289. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Difford, I. D. (1920). The Story of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps, 1915–1919. Cape Town: Hortors. OCLC 13300378. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Downes, W. D. (1919). With the Nigerians in German East Africa. London: Methuen. OCLC 10329057. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Fendall, C. P. (1992) [1921]. The East African Force 1915–1919 (Battery Press ed.). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 978-0-89839-174-9. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Frenssen, G. (1914) [1906]. Peter Moors Fahrt nach Südwest [Peter Moor's Journey to South-West Africa: A Narrative of the German Campaign] (Houghton Mifflin, NY ed.). Berlin: Grote. OCLC 2953336. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Gardner, B. (1963). On to Kilimanjaro. Philadelphia: Macrae Smith. ISBN 978-1-111-04620-0.

- Hodges, G., ed. (1999). The Carrier Corps: The Story of the Military Labor Forces in the Conquest of German East Africa, 1914–1919 (2nd revised ed.). Nairobi: Nairobi University Press. OCLC 605134579.

- Hoyt, E. P. (1968). The Germans Who Never Lost. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. ISBN 978-0-09-096400-0.

- Millais, J. G. (1919). Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O., Capt. 25th Royal Fusiliers. London: Longmans, Green. OCLC 5322545. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Mosley, L. (1963). Duel for Kilimanjaro: An Account of the East African Campaign 1914–1918. New York: Ballantine Books. OCLC 655839799.

- Northrup, D. (1988). Beyond the Bend in the River: African Labor in Eastern Zaire, 1865–1940. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies. ISBN 978-0-89680-151-6. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Patience, K. (1997). Konigsberg: A German East African Raider (2001 revised ed.). Bahrain: Author. OCLC 223264994.

- Rutherford, A. (2001). Kaputala: The Diary of Arthur Beagle & The East Africa Campaign 1916–1918. Hand Over Fist Press. ISBN 978-0-9540517-0-9.

- Sheppard, S. H. (1919). Some Notes on Tactics in the East African Campaign. India: Simla?. OCLC 609954711. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Sibley, J. R. (1973). Tanganyikan Guerilla. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-09801-6.

- Stapleton, T. (2005). The Rhodesia Native Regiment and the East Africa Campaign of the First World War. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-498-0.

- Stevenson, W. (1981). The Ghosts of Africa. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-29793-8.

- Whittall, W. (1917). With Botha and Smuts in Africa. London: Cassell. OCLC 3504908. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Young, F. B. (1917). Marching on Tanga. New York: E. P. Dutton. OCLC 717640690.

Journals

- Alexander, G. A. M. (1961). "The Evacuation of Kasama in 1918". The Northern Rhodesia Journal. IV (5). ISSN 0549-9674. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

Theses

- Anderson, R. (2001). World War I in East Africa, 1916–1918. theses.gla.ac.uk (PhD). University of Glasgow. OCLC 498854094. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.252464. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

External links

- The Evacuation of Kasama in 1918

- The German East Africa Campaign 1914–1918

- The War with Germany in East Africa

- Rutherford, Alan. Kaputala, 2nd edition, Hand Over Fist Press, 2014.

- The Zeppelin Airship Era

- Cana, Frank R. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 30 (12th ed.). pp. 875–886.

- Digre, Brian : Colonial Warfare and Occupation (Africa), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.