Oghuz Turks

The Oghuz Turks (Middle Turkic: ٱغُز, romanized: Oγuz) were a western Turkic people who spoke the Oghuz branch of the Turkic language family.[2] In the 8th century, they formed a tribal confederation conventionally named the Oghuz Yabgu State in Central Asia. Today, much of the populations of Turkey, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are descendants of Oghuz Turks. Byzantine sources call them Uzes (Οὐ̑ζοι, Ouzoi).[3] The term Oghuz was gradually supplanted by the terms Turkmen and Turcoman (Ottoman Turkish: تركمن, romanized: Türkmen or Türkmân) by 13th century.[4]

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Before 11th century: Turkestan From 11th century: Anatolia · Caucasus · Greater Khorasan · Cyprus · Mesopotamia · Balkans · North Africa Historical: Yedisan · Crimea | |

| Languages | |

| Oghuz languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam (Sunni · Alevi · Bektashi · Twelver Shia) Minority: Irreligion · Christianity · Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Azerbaijanis[1] · Turkmens[1] · Turkish people[1] |

The Oghuz confederation migrated westward from the Jeti-su area after a conflict with the Karluk allies of the Uyghurs. In the 9th century, the Oghuz from the Aral steppes drove Pechenegs westward from the Emba and Ural River region. In the 10th century, the Oghuz inhabited the steppe of the rivers Sari-su, Turgai and Emba north of Lake Balkhash in modern-day Kazakhstan.[5]

They embraced Islam and adapted their traditions and institutions to the Islamic world, emerging as empire-builders with a constructive sense of statecraft. In the 11th century, the Seljuk Oghuz clan entered Persia, where they founded the Great Seljuk Empire. The same century, a Tengriist Oghuz clan, also known as Uzes or Torks, overthrew Pecheneg supremacy in the frontier of the Russian steppes; those who settled along the frontier were gradually Slavicized; the almost feudal Black Hat principality grew with its own military aristocracy.[6] Others, harried by the Kipchak Turks, crossed the lower Danube and invaded the Balkans,[7] where they were stopped by a plague and became mercenaries for the Byzantine imperial forces (1065).[8] Oghuz warriors served in almost all Islamic armies of the Middle East from the 1000s onwards, and as far as Spain and Morocco.[6]

In the late 13th century after the fall of the Seljuks, the Ottoman dynasty gradually conquered Anatolia with an army also predominantly of Oghuz,[9] besting other local Oghuz Turkish states.[10] In legend, the founder Osman's genealogy traces to Oghuz Khagan, the legendary ancient ancestor of Turkic people,[11] giving the Ottoman sultans primacy among Turkish monarchs.[12] The dynasties of Khwarazmians, Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu, Ottomans and Afsharids are also believed to descend from the Oghuz-Turkmen tribes of Begdili, Yiva, Bayandur, Kayi and Afshar respectively.[13]

Name and language

The name Oghuz is a Common Turkic word for "tribe". By the 10th century, Islamic sources were calling them Muslim Turkmens, as opposed to those of Tengrist or Buddhist religion; and by the 12th century this term was adopted into Byzantine usage, as the Oghuzes were overwhelmingly Muslim.[14] The name "Oghuz" fell out of use by 13th century.[4]

Linguistically, the Oghuz belong to the Common Turkic speaking group, characterized by sound correspondences such as Common Turkic /-š/ versus Oghuric /-l/ and Common Turkic /-z/ versus Oghuric /-r/.Within the Common Turkic group, the Oghuz languages share these innovations: loss of Proto-Turkic gutturals in suffix anlaut, loss of /ɣ/ except after /a/, /g/ becoming either /j/ or lost, voicing of /t/ to /d/ and of /k/ to /g/, and */ð/ becomes /j/.[15]

Their language belongs to the Oghuz group of the Turkic languages family. Kara-Khanid scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari wrote that of all the Turkic languages, that of the Oghuz was the simplest. He also observed that long separation had led to clear differences between the western Oghuz and Kipchak language and that of the eastern Turks.[16]

Origins

.jpg.webp)

Turkologist Peter Benjamin Golden (2011) used Proto-Turkic lexical items about the climate, topography, flora, fauna, people's modes of subsistence in the Proto-Turkic Urheimat to locate it in the southern, taiga-steppe zone of the Sayan-Altay region.[17] Recently, the early Turkic peoples are proposed to descend from agricultural communities in Northeast Asia who moved westwards into Mongolia in the late 3rd millennium BC, where they adopted a pastoral lifestyle.[18][19][20][21][22] By the early 1st millennium BC, these peoples had become equestrian nomads.[18] In subsequent centuries, the steppe populations of Central Asia appear to have been progressively replaced and Turkified by East Asian nomadic Turks, moving out of Mongolia.[23][24]

In early times, they practiced a Tengrist religion, erecting many carved wooden funerary statues surrounded by simple stone balbal monoliths and holding elaborate hunting and banqueting rituals.[25]

During the 2nd century BC, according to ancient Chinese sources, a steppe tribal confederation known as the Xiongnu and their allies, the Wusun (probably an Indo-European people) defeated the neighboring Indo-European-speaking Yuezhi and drove them out of western China and into Central Asia. Various scholarly theories link the Xiongnu to Turkic peoples and/or the Huns. Bichurin claimed that the first usage of the word Oghuz appears to have been the title of Oğuz Kağan, whose biography shares similarities with the biography, recorded by Han Chinese, of Xiongnu leader Modu Shanyu (or Mau-Tun),[26][27] who founded the Xiongnu Empire. However, Oghuz Khan narratives were actually collected in Compendium of Chronicles by Ilkhanid scholar Rashid-al-Din in the early 14th century.[28]

Sima Qian recorded the name Wūjiē 烏揭 (LHC: *ʔɔ-gɨat) or Hūjiē 呼揭 (LHC: *xɔ-gɨat), of a people hostile to the Xiongnu and living immediately west of them, in the area of the Irtysh River, near Lake Zaysan.[29] Golden suggests that these might be Chinese renditions of *Ogur ~ *Oguz, yet uncertainty remains.[30] According to one theory, Hūjiē is just another transliteration of Yuezhi and may refer to the Turkic Uyghurs; however, this is controversial and has few scholarly adherents.[31]

Yury Zuev (1960) links the Oghuz to the Western Turkic tribe 姑蘇 Gūsū < (MC *kuo-suo) in the 8th-century encyclopaedia Tongdian[32] (or erroneously Shǐsū 始蘇 in the 11th century Zizhi Tongjian[33]). Zuev also noted a parallel between two passages:

- one from the 8th-century Taibo Yinjing (太白陰經) "Venus's Secret Classic" by Li Quan (李筌) which mentioned the 三窟 ~ 三屈 "Three Qu" (< MC *k(h)ɨut̚) after the 十箭 Shí Jiàn "Ten Arrows" (OTrk 𐰆𐰣:𐰸 On Oq) and Jĭu Xìng "Nine Surnames" (OTrk 𐱃𐰸𐰆𐰔:𐰆𐰍𐰔 Toquz Oğuz);[34] and

- another from al-Maṣudi's Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems, which mentioned the three hordes of the Turkic Ġuz[35]

Based on those sources, Zuev proposes that in the 8th century the Oghuzes were located outsides of the Ten Arrows' jurisdiction, west of the Altai mountains, near lake Issyk-Kul, Talas river's basin and seemingly around the Syr Darya basin, and near the Chumul, Karluks, Qays, Quns, Śari, etc. who were mentioned by al-Maṣudi and Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi.[36]

According to Ahmad ibn Fadlan, the Oghuz were nomads, but also had cultivated crops, and the economy was based on a semi-pastoralist lifestyle.[37]

Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos mentioned the Uzi and Mazari (Hungarians) as neighbours of the Pechenegs.[38]

By the time of the Orkhon inscriptions (8th century AD) "Oghuz" was being applied generically to all inhabitants of the Göktürk Khaganate.[39] Within the khaganate, the Oghuz community gradually expanded, incorporating other tribes.[40] A number of subsequent tribal confederations bore the name Oghuz, often affixed to a numeral indicating the number of united tribes. These include references to the simple Oguz, Üch-Oghuz ("three Oghuz"), Altï Oghuz ("six Oghuz"), possibly the Otuz Oghuz ("thirty Oghuz"), Sekiz-Oghuz ("eight Oghuz"), and the Tokuz-Oghuz ("nine Oghuz"),[41] who originally occupied different areas in the vicinity of the Altai Mountains. Golden (2011) states Transoxanian Oghuz Turks who founded the Oghuz Yabgu State were not the same tribal confederation as the Toquz Oghuz from whom emerged the founders of Uyghur Khaganate. Istakhri and Muhammad ibn Muhmad al-Tusi kept the Toquz Oghuz and Oghuz distinct[42] and Ibn al-Faqih mentioned: "the infidel Turk-Oghuz, the Toquz-Oghuz, and the Qarluq"[43] Even so, Golden notes the confusion in Latter Göktürks' and Uyghurs' inscriptions, where Oghuz apparently referred to Toquz Oghuz or another tribal grouping, who were also named Oghuz without a prefixed numeral; this confusion is also reflected in Sharaf al-Zaman al-Marwazi, who listed 12 Oghuz tribes, who were ruled by a "Toquz Khaqan" and some of whom were Toquz-Oghuz, on the border of Transoxiana and Khwarazm. At most, the Oghuz were possibly led by a core group of Toquz Oghuz clans or tribes.[44]

Noting that the mid-8th-century Tariat inscriptions, in Uyghur khagan Bayanchur's honor, mentioned the rebellious Igdir tribe who had revolted against him, Klyashtorny considers this as one piece of "direct evidence in favour of the existence of kindred relations between the Tokuz Oguzs of Mongolia, The Guzs of the Aral region, and modern Turkmens", besides the facts that Kashgari mentioned the Igdir as the 14th of 22 Oghuz tribes;[45] and that Igdirs constitute part of the Turkmen tribe Chowdur.[46] The Shine Usu inscription, also in Bayanchur's honor, mentioned the Nine-Oghuzes as "[his] people" and that he defeated the Eight-Oghuzes and their allies, the Nine Tatars, three times in 749.;[47] according to Klyashtorny[48] and Czeglédy,[49] eight tribes of the Nine-Oghuzes revolted against the leading Uyghur tribe and renamed themselves Eight-Oghuzes.

Ibn al-Athir, an Arab historian, claimed that the Oghuz Turks were settled mainly in Transoxiana, between the Caspian and Aral Seas, during the period of the caliph Al-Mahdi (after 775 AD). By 780, the eastern parts of the Syr Darya were ruled by the Karluk Turks and to their west were the Oghuz. Transoxiana, their main homeland in subsequent centuries became known as the "Oghuz Steppe".

During the period of the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun (813–833), the name Oghuz starts to appear in the works of Islamic writers. The Book of Dede Korkut, a historical epic of the Oghuz, contains historical echoes of the 9th and 10th centuries but was likely written several centuries later.[50]

Physical appearance

Al-Masudi described Yangikent's Oghuz Turks as "distinguished from other Turks by their valour, their slanted eyes, and the smallness of their stature". Stone heads of Seljuq elites kept at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed East Asian features.[51] Over time, Oghuz Turks' physical appearance changed. Rashid al-Din Hamadani stated that "because of the climate their features gradually changed into those of Tajiks. Since they were not Tajiks, the Tajik peoples called them turkmān, i.e. Turk-like (Turk-mānand)"[lower-alpha 1] Ḥāfiẓ Tanīsh Mīr Muḥammad Bukhārī also related that the Oghuz' ‘Turkic face did not remain as it was’ after their migration into Transoxiana and Iran. Khiva khan Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur wrote in his Chagatai-language treatise Genealogy of the Turkmens that "their chin started to become narrow, their eyes started to become large, their faces started to become small, and their noses started to become big’ after five or six generations". Ottoman historian Mustafa Âlî commented in Künhüʾl-aḫbār that Anatolian Turks and Ottoman elites are ethnically mixed: "Most of the inhabitants of Rûm are of confused ethnic origin. Among its notables there are few whose lineage does not go back to a convert to Islam."[54]

Social units

The militarism that the Oghuz empires were very well known for was rooted in their centuries-long nomadic lifestyle. In general, they were a herding society which possessed certain military advantages that sedentary societies did not have, particularly mobility. Alliances by marriage and kinship, and systems of "social distance" based on family relationships were the connective tissues of their society.

In Oghuz traditions, "society was simply the result of the growth of individual families". But such a society also grew by alliances and the expansion of different groups, normally through marriages. The shelter of the Oghuz tribes was a tent-like dwelling, erected on wooden poles and covered with skin, felt, or hand-woven textiles, which is called a yurt.

Their cuisine included yahni (stew), kebabs, Toyga soup (meaning "wedding soup"), Kımız (a traditional drink of the Turks, made from fermented horse milk), Pekmez (a syrup made of boiled grape juice) and helva made with wheat starch or rice flour, tutmac (noodle soup), yufka (flattened bread), katmer (layered pastry), chorek (ring-shaped buns), bread, clotted cream, cheese, yogurt, milk and ayran (diluted yogurt beverage), as well as wine.

Social order was maintained by emphasizing "correctness in conduct as well as ritual and ceremony". Ceremonies brought together the scattered members of the society to celebrate birth, puberty, marriage, and death. Such ceremonies had the effect of minimizing social dangers and also of adjusting persons to each other under controlled emotional conditions.

Patrilineally related men and their families were regarded as a group with rights over a particular territory and were distinguished from neighbours on a territorial basis. Marriages were often arranged among territorial groups so that neighbouring groups could become related, but this was the only organizing principle that extended territorial unity. Each community of the Oghuz Turks was thought of as part of a larger society composed of distant as well as close relatives. This signified "tribal allegiance". Wealth and materialistic objects were not commonly emphasized in Oghuz society and most remained herders, and when settled they would be active in agriculture.

Status within the family was based on age, gender, relationships by blood, or marriageability. Males, as well as females, were active in society, yet men were the backbones of leadership and organization. According to the Book of Dede Korkut, which demonstrates the culture of the Oghuz Turks, women were "expert horse riders, archers, and athletes". The elders were respected as repositories of both "secular and spiritual wisdom".

Homeland in Transoxiana

In the 700s, the Oghuz Turks made a new home and domain for themselves in the area between the Caspian and Aral seas, a region that is often referred to as Transoxiana, the western portion of Turkestan. They had moved westward from the Altay mountains passing through the Siberian steppes and settled in this region, and also penetrated into southern Russia and the Volga from their bases in west China. In the 11th century, the Oghuz Turks adopted Arabic script, replacing the Old Turkic alphabet.[55]

In his accredited 11th-century treatise titled Diwan Lughat al-Turk, Karakhanid scholar Mahmud of Kashgar mentioned five Oghuz cities named Sabran, Sitkün, Qarnaq, Suğnaq, and Qaraçuq (the last of which was also known to Kashgari as Farab,[56] now Otrar; situated near the Karachuk mountains to its east). The extension from the Karachuk Mountains towards the Caspian Sea (Transoxiana) was called the "Oghuz Steppe Lands" from where the Oghuz Turks established trading, religious and cultural contacts with the Abbasid Arab caliphate who ruled to the south. This is around the same time that they first converted to Islam and renounced their Tengriism belief system. The Arab historians mentioned that the Oghuz Turks in their domain in Transoxiana were ruled by a number of kings and chieftains.

It was in this area that they later founded the Seljuk Empire, and it was from this area that they spread west into western Asia and eastern Europe during Turkic migrations from the 9th until the 12th century. The founders of the Ottoman Empire were also Oghuz Turks.

Poetry and literature

Oghuz Turkish literature includes the famous Book of Dede Korkut which was UNESCO's 2000 literary work of the year, as well as the Oghuzname, Battalname, Danishmendname, Köroğlu epics which are part of the literary history of Azerbaijanis, Turks of Turkey and Turkmens. The modern and classical literature of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Turkmenistan are also considered Oghuz literature since it was produced by their descendants.

The Book of Dede Korkut is a valuable collection of epics and stories, bearing witness to the language, the way of life, religions, traditions, and social norms of the Oghuz Turks in Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran (West Azerbaijan, Golestan) and parts of Central Asia including Turkmenistan.

Oghuz and Yörüks

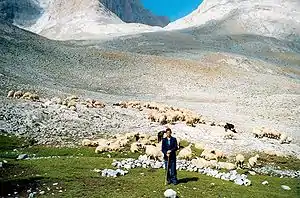

_p010_YOUROUK_ENCAMPMENT_IN_THE_TAURUS.jpg.webp)

Yörüks are an Oghuz ethnic group, some of whom are still semi-nomadic, primarily inhabiting the mountains of Anatolia and partly Balkan peninsula.[57][58] Their name derives from the verb from Chagatai language, yörü- "yörümek" (to walk), but Western Turkic yürü- (yürümek in infinitive), which means "to walk", with the word Yörük or Yürük designating "those who walk, walkers".[59][60][61]

The Yörük to this day appear as a distinct segment of the population of Macedonia and Thrace where they settled as early as the 14th century.[62] While today the Yörük are increasingly settled, many of them still maintain their nomadic lifestyle, breeding goats and sheep in the Taurus Mountains and further eastern parts of mediterranean regions (in southern Anatolia), in the Pindus (Epirus, Greece), the Šar Mountains (North Macedonia), the Pirin and Rhodope Mountains (Bulgaria) and Dobrudja. An earlier offshoot of the Yörüks, the Kailars or Kayılar Turks were amongst the first Turkish colonists in Europe,[62] (Kailar or Kayılar being the Turkish name for the Greek town of Ptolemaida which took its current name in 1928)[63] formerly inhabiting parts of the Greek regions of Thessaly and Macedonia. Settled Yörüks could be found until 1923, especially near and in the town of Kozani.

List of Oghuz dynasties

Traditional tribal organization

Mahmud al-Kashgari listed 22 Oghuz tribes in Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk. Kashgari further wrote that "In origin they are 24 tribes, but the two Khalajiyya tribes are distinguished from them [the twenty-two] in certain respects[lower-alpha 2] and so are not counted among them. This is the origin".[64][65]

Later, Charuklug from Kashgari's list would be omitted. Rashid-al-Din and Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur added three more: Kïzïk, Karkïn, and Yaparlï, to the list in Jami' al-tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles) and Shajare-i Türk (Genealogy of the Turks), respectively.[66] According to Selçukname, Oghuz Khagan had 6 children (Sun – Gün, Moon – Ay, Star – Yıldız, Sky – Gök, Mountain – Dağ, Sea – Diŋiz), and all six would become Khans themselves, each leading four tribes.[67]

Bozoks (Gray Arrows)

Üçoks (Three Arrows)

- Gök Han

- Dağ Han

- Salur (Kadi Burhan al-Din, Salghurids and Karamanids; see also: Salars)

- Eymür

- Alayuntlu

- Yüreğir (Ramadanids)

- Diŋiz Han

- Iğdır[28]

- Büğdüz

- Yıva (Qara Qoyunlu and Oghuz Yabgu State)

- Kınık (founders of the Seljuk Empire)[70]

| Tribe name | Middle Turkic[71] | Turkish language (Turkey) |

Azerbaijani language (Azerbaijan) |

Turkmen language (Turkmenistan) |

Meaning | Ongon | Tamgha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kayı (tribe) | Kayığ (قَيِغْ) | Kayı | Qayı | Gaýy | strong | Gyrfalcon (sungur) |

|

| Bayat (tribe) | Bayat (بَياتْ) | Bayat | Bayat | Baýat | rich | Eurasian eagle-owl (puhu) |

|

| Alkaevli (tribe) | Alkabölük (اَلْقابُلُكْ) | Alkaevli | Ağevli | Agöýli | white housed | Common kestrel (küyenek) |

|

| Karaevli (tribe) | Karabölük (قَرَبُلُكْ) | Karaevli | Qaraevli | Garaöýli | black housed | Lesser kestrel (küyenek sarı) |

|

| Yazır (tribe) | Yazgır (ىَزْغِرْ) | Yazır | Yazır | Ýazyr | spread | Merlin (turumtay) |

|

| Döğer | Tüger (تُوكَرْ) / (ثُكَرْ) | Döğer | Döğər | Tüwer | gatherer | ? (küçügen) |

|

| Dodurga | Tutırka (تُوتِرْقا) | Dodurga | Dodurqa | Dodurga | country gainer | ? (kızıl karcığay) |

|

| Yaparlı (tribe) | Yaparlı | Yaparlı | Ýaparly | nice-smelling | ? | ||

| Afshar (tribe) | Afşar (اَفْشارْ) | Avşar, Afşar | Əfşar | Owşar | obedient, agile | Bonelli's eagle (cura laçın) |

|

| Qiziq | Kızık | Qızıq | Gyzyk | forbidden | Northern goshawk (çakır) |

||

| Beğdili | Begtili (بَكْتِلى) | Beğdili | Bəydili | Begdili | reputable | Great crested grebe (bahri) |

|

| Karkın (tribe) | Karkın, Kargın | Karqın | Garkyn | black leather | Northern goshawk (çakır) |

||

| Bayandur | Bayundur (بايُنْدُرْ) | Bayındır | Bayandur | Baýyndyr | wealthy soil | Peregrine falcon (laçın) |

|

| Pecheneg | Beçenek (بَجَنَكْ) | Peçenek | Peçeneq | Beçene | one who makes | Eurasian Magpie (ala toğunak) |

|

| Chowdur | Çuvaldar (جُوَلْدَرْ) | Çavuldur | Çavuldur | Çowdur | famous | ? (buğdayınık) |

|

| Chepni (tribe) | Çepni (جَبْني) | Çepni | Çəpni | Çepni | one who attacks the enemy | Huma bird (humay) |

|

| Salur (tribe) | Salgur (سَلْغُرْ) | Salur | Salur | Salyr | sword swinger | Golden eagle (bürgüt) |

|

| Ayrums | Eymür (اَيْمُرْ) | Eymür | Eymur | Eýmir | being good | Eurasian hobby (isperi) |

|

| Ulayuntluğ (tribe) | Ulayundluğ (اُوﻻيُنْدْلُغْ) | Ulayundluğ | Alayuntluq | Alaýöntli | with a pied horse | Red-footed falcon (yağalbay) |

|

| Yüreğir (tribe) | Üregir (اُرَكِرْ) Yüregir (يُرَكِرْ) |

Yüreğir, Üreğir | Yürəgir | Üregir | order finder | ? biku |

|

| İğdir (tribe) | İgdir (اِكْدِرْ) | İğdir | Iğdır | Igdir | being good | Northern goshawk (karcığay) |

|

| Büğdüz (tribe) | Bügdüz (بُكْدُزْ) | Büğdüz | Bügdüz | Bügdüz | modest | Saker falcon (itelgi) |

|

| Yıva | Iwa (اِڤـا) Yıwa (يِڤـا) |

Yıva | Yıva | Ywa | high ranked | Northern goshawk (tuygun) |

|

| Kınık (tribe) | Kınık (قِنِقْ) | Kınık | Qınıq | Gynyk | saint | Northern goshawk (cura karcığay) |

List of Oghuz ethnic groups

Other Oghuz sub-ethnic groups and tribes

Anatolia and Caucasus

- Anatolia

- Abdal of Turkey

- Yörüks

- Tahtacı

- Varsak

- Barak

- Karakeçili (Black Goat Turkomans)

- Manav

- Atçeken

- Küresünni

- Chepni

- Caucasus

- Azerbaijanis in Armenia

- Azerbaijanis in Turkey

- Azerbaijanis in Georgia

- Terekeme people

- Qarapapaq

- Karadaghis

- Javanshir clan

- Trukhmen

- Turks in Abkhazia

- Meskhetian Turks

- Cyprus

Balkans

Central Asia

Arab world

Notes

- This folk-etymology had been attested in Al-Biruni and Mahmud al-Kashgari, the latter a native Middle Turkic speaker.[52] However, this mixed Turkic-Persian etymology is now considered incorrect; instead, Türkmen is now etymologized as from ethnonym Türk plus strengthening suffix -men, meaning "'most Turkish of the Turks' or 'pure-blooded Turks.'".[53]

- Ar.: infaradatā ˤanhā bi-baˤḍ- al-aśyāˀ; alternative translation "separated from them with some of the belongings"

References

- Barthold (1962)""The book of my grandfather Korkut" ("Kitab-i dedem Korkut") is an outstanding monument of the medieval Oghuz heroic epic. Three modern Turkic-speaking peoples – Turkmens, Azerbaijanis and Turks – are ethnically and linguistically related to the medieval Oghuzes. For all these peoples, the epic legends deposited in the "Book of Korkut" represent an artistic reflection of their historical past."

- The modern Turkish, Turkmen and Azerbaijani languages are all Oghuz languages.

- Omeljan Pritsak, "Uzes", in Alexander P. Kazhdan, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Lewis, G. The Book of Dede Korkut. Penguin Books, 1974, p. 10.

- Grousset, R. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1991, p. 148.

- Nicolle, David; Angus Mcbride (1990). Attila and the Nomad Hordes. Osprey Publishing. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-85045-996-6.

The Oghuz had a very distinctive culture. Their hunting and banqueting rituals were as elaborate as those of the Gökturks from whom they... ...like some Pechenegs and Torks, settled along Russia's steppe frontier after being forced out... Here an almost feudal 'Black Hat' principality grew up with its own military aristocracy being accepted by the Russian elite on equal terms...

- Grousset, R. The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press, 1991, p. 186.

- Hupchick, D. The Balkans. Palgrave, 2002, p. 62.

- Lewis, p. 9.

- Selcuk Aksin Somel, (2003), Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, p. 217

- "Monument "Oghuz Khan and Sons"". Arara Central Asia. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- Colin Imber, (2002), The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650, p. 95

- Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur; "The Genealogy of the Turkmens" (in Russian). 1897.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Elizabeth A. Zachariadou, "Turkomans", in Alexander P. Kazhdan, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Golden, Peter B. An Introduction to the History of Turkic Peoples (1992). p. 21-22

- D. T. Potts, (2014), Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era, p. 177

- Golden 2011, pp. 35–37.

- Robbeets 2017, pp. 216–18.

- Robbeets 2020.

- Nelson et al. 2020.

- Li et al. 2020.

- Uchiyama et al. 2020.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, pp. 4–5. "These results suggest that Turkic cultural customs were imposed by an East Asian minority elite onto central steppe nomad populations… The wide distribution of the Turkic languages from Northwest China, Mongolia and Siberia in the east to Turkey and Bulgaria in the west implies large-scale migrations out of the homeland in Mongolia.

- Lee & Kuang 2017, p. 197. "Both Chinese histories and modern DNA studies indicate that the early and medieval Turkic peoples were made up of heterogeneous populations. The Turkicisation of central and western Eurasia was not the product of migrations involving a homogeneous entity, but that of language diffusion."

- Nicolle, David; McBride, Angus (2007). Attila and the nomad hordes. Osprey military Elite series. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-996-8.

- Bichurin, N. Ya., "Collection of information on peoples in Central Asia in ancient times", vol. 1, Sankt Petersburg, 1851, pp. 56–57

- Taskin V. S., transl., "Materials on history of Sünnu", 1968, vol. 1, p. 129

- Bınbaş, İlker Evrım (2010). "Oguz Khan Narratives". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shiji, c. 90 BC: 110.

- Golden, Peter B., “Oq and Oğur ~ Oğuz”, Turkic Languages, 16/2 (2012), pp. 155–199

- Torday, L., Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. The Durham Academic Press, 1997, pp. 220–221.

- Du You et al. Tongdian, vol. 199

- Sima Guang et al. Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 199

- Li Quan, Taibo Yinjing "Vol. 1-3", Zhejiang University Library Copy. p. 99 of 102 or Shoushange congshu 守山閣叢書 version p. 51 of 222

- Al-Masudi Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems vol. 1 p. 238-239. translated by Aloys Spreger

- Zuev, Yu. "Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms" (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuiyao" of 8–10th centuries), Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, 1960, p. 126, 133–134 (in Russian)

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300) (2 Vols). Boston: BRILL. p. 152. ISBN 978-90-04-39519-0. OCLC 1111434007.

- Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos. De Administrando Imperio. Chapter 37.

... iisque conterminos fuisse populos illos qui Mazari atque Uzi cognominantur ...

- Faruk Sümer, Oğuzlar (2007). TDV Islam Ansiklopedisi (PDF) (in Turkish). Vol. 33. pp. 325–330.

- "Oguz". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Golden, Peter B. (1972) "The Migrations of the Oğuz" "The Migrations of the Oğuz"] in Archivum Ottomanicum 4, p. 48

- Golden, Peter B. The Turkic Word of Mahmud al-Kashgari, p. 507-511

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 198

- Golden (1992) p. 206-207

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. (1982). Part I p. 101-102

- Klyashtorny, S.G. (1997) "The Oguzs of the Central Asia and The Guzs of the Aral Region" in International Journal of Eurasian Studies 2

- "Moghon Shine Usu Inscription" text at Türik Bitig

- Klyashtorny, S.G. (1997)

- cited in Kamalov, A. (2003) "The Moghon Shine Usu Insription as the Earliest Uighur Historical Annals", Central Asiatic Journal. 47 (1). p. 83 of p. 77-90

- Alstadt, Audrey. The Azerbaijani Turks, p. 11. Hoover Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8179-9182-4

- Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 207-208 of 197–239

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. (1982). Part II. p. 363

- Clark, Larry (1996). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Harrassowitz. p. 4. ISBN 9783447040198.,Annanepesov, M. (1999). "The Turkmens". In Dani, Ahmad Hasan (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 127. ISBN 9789231038761.,Golden, Peter (1992). An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples. Harrassowitz. pp. 212–213..

- Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 208 of 197–239

- C. E. Bosworth, The Ghaznavids:994–1040, (Edinburgh University Press, 1963), 216.

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk. Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. Series: Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. (1982). "Part I", p. 270, 329, 333, 352, 353, 362

- N. K. Singh, A. M. Khan, Encyclopaedia of the world Muslims: Tribes, Castes and Communities, Vol.4, Delhi 2001, p.1542

- Grolier Incorporated, Academic American Encyclopedia, vol.20, 1989, p.34

- Sir Gerard Clauson, An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth Century Turkish, Oxford 1972, p.972

- Turkish Language Association – TDK Online Dictionary. Yorouk Archived April 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, yorouk Archived April 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "yuruk". Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged. Merriam-Webster. 2002.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 217.

- Ptolemaida.net – History of Ptolemaida web page Archived 2011-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk. Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. Series: Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. (1982). "Part I". p. 101-102, 362–363

- Minorsky, V. "Commentary on Hudud al-'Alam's "§24. Khorasian Marches" pp. 347–348

- Golden, Peter B. (2015). "The Turkic World in Mahmûd al-Kâshgharî" in Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology. 7. p. 513-516

- "YEREL BILGILER" (PDF). Kizilagil.de. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Some Ottoman genealogies claim, perhaps fancifully, descent from Kayı.", Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in World History, pp. 50, 2005, Oxford University Press

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Kafesoğlu, İbrahim. Türk Milli Kültürü. Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü, 1977. page 134

- Divanü Lûgat-it-Türk, translation Besim Atalay, Turkish Language Association press:521, Ankara 1941, book: 1, page: 55-58

Sources

- Barthold, V., ed. (1962). The book of my grandfather Korkut. Moscow and Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (9 May 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..369D. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. hdl:1887/3202709. PMID 29743675. S2CID 13670282. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Golden, Peter B. (2011). Studies on the Peoples and Cultures of the Eurasian Steppes. Editura Academiei Române – Editura Istro. ISBN 978-973-27-2152-0.

- Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. Brill. 19 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340089. ISSN 2210-5018. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Li, Tao; et al. (June 2020). "Millet agriculture dispersed from Northeast China to the Russian Far East: Integrating archaeology, genetics, and linguistics". Archaeological Research in Asia. Elsevier. 22 (100177): 100177. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2020.100177. hdl:21.11116/0000-0005-D82B-8.

- Nelson, Sarah; et al. (14 February 2020). "Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production". Evolutionary Human Sciences. Cambridge University Press. 2 (e5): e5. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.4. hdl:21.11116/0000-0005-AD07-1. PMC 10427276. PMID 37588355.

- Robbeets, Martine (1 January 2017). "Austronesian influence and Transeurasian ancestry in Japanese". Language Dynamics and Change. Brill. 8 (2): 210–251. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702005. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002E-8635-7. ISSN 2210-5832. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Robbeets, Martine (2020). "The Transeurasian homeland: where, what and when?". In Robbeets, Martine; Savelyev, Alexander (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Transeurasian Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880462-8.

- Uchiyama, Junzo; et al. (21 May 2020). "Populations dynamics in Northern Eurasian forests: a long-term perspective from Northeast Asia". Evolutionary Human Sciences. Cambridge University Press. 2: e16. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.11. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-7733-A. PMC 10427466. PMID 37588381.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Further reading

- Grousset, R., The Empire of the Steppes, 1991, Rutgers University Press

- Nicole, D., Attila and the Huns, 1990, Osprey Publishing

- Lewis, G., The Book of Dede Korkut, "Introduction", 1974, Penguin Books

- Minahan, James B. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Press, 2000. page 692

- Aydın, Mehmet. Bayat-Bayat boyu ve Oğuzların tarihi. Hatiboğlu Yayınevi, 1984. web page

External links

- Golden, Peter; Bosworth, C. Edmund (2002). "ḠOZZ". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. XI, Fasc. 2. pp. 184–187.

- Golden, Peter B. (2020). "Oghuz". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- The Book of Dede Korkut (pdf format) at the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative

- Similarities between the epics of Dede Korkut and Alpamysh

- A page dedicated to Oguz Khan

- The Old Turkic Inscriptions.