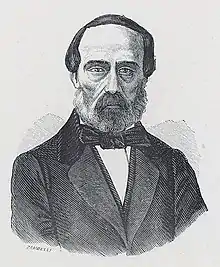

Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio

Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio (24 April 1796 - 4 August 1878) was a Lombard aristocrat who became a long-standing patriot activist-politician. He was consistent in his backing of Italian unification between 1820 and its accomplishment.[1][2]

Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio | |

|---|---|

Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio, Aristide Calani, 1861 | |

| Born | Giorgio Guido Pallavicino Trivulzio 24 April 1796 |

| Died | 4 August 1878 |

| Occupation(s) | Patriot (Italian unification activist Politician Senator |

| Parents |

|

Biography

Provenance and early years

Giorgio Guido Pallavicino Trivulzio was born into an aristocratic family in Milan approximately one year before the incorporation of northern and central Italy into the growing body of territories that would be reconfigured and rebranded a few years later as parts of the First French Empire. His father was the Marquis Giorgio Pio: his mother was the Countess Anna Besozzi. Pallavicino Trivulzio inherited further titles as he grew up. Little is known of his early years. His father died when he was just seven, leaving his mother to attend to his upbringing. After he died Sebastiano Tecchio, the president of the senate in which he had served, delivered an affectionate oration in which he spoke of Pallavicino Trivulzio's childhood in a privileged single parent family. His mother, Anna was an educated woman who saw to it that her son was well taught. Contemporary literature reflected Italy's condition of disunity and subservience to the Napoleonic empire: she took care to see that his reading concentrated of the classical authors and orators of ancient Greece and Rome. She forbad the servants from addressing the child by his title as "Marquis" or stepping in to help him to undertake tasks that he should be perfectly well able to undertake for himself, and she inculcated in him the virtues of "severe frugality". For some time he was sent to a boarding school, on which he would look back without pleasure. Aside from the sense of rejection and what he perceived as an excess of religious practices, he found the quality of the actual teaching "superficial and pedantic".[1][3]

Uprising against Austrian hegemony in 1820/21

Starting in 1814, he was able to undertake a succession of lengthy trips away from home, taking in the Italian peninsular and several other European countries. After 1815, there was a backlash on the part of European governments against all the changes that had taken place during the quarter century following the French revolution, which for the Italian territories now under Austrian hegemony involved strenuous efforts by the authorities to thwart any signs of liberalism or Italian nationalism. A series of anti-Austrian riots broke out during 1820/21 in which Pallavicino Trivulzio participated. During or before January 1821, he joined the secret conspiratorial society being formed by Federico Confalonieri who was recruiting supporters from across Lombardy in preparation for some sort of military insurrection.[1][4] During March 1821, as rioting broke out in the neighbouring Piedmont-Sardinia (which was not formally under Austrian control) Pallavicino Trivulzio and Gaetano De Castillia together visited Turin on behalf of Confalonieri and secured an interview with the regent, whom they tried to persuade to send Piedmontese troops cross the border into Lombardy and take on the Austrians. According to one version of the interview, he subsequently confessed to interrogators that he had secured the assurance of Charles Albert that the Lombard cause was "sacred" to the government of Piedmont, although Pallavicino Trivulzio own recollection of the meeting seem later to have changed.[1]

From Turin, Pallavicino Trivulzio escaped briefly to the north, crossing into Switzerland, before returning home to Milan. On learning that de Castillia had already been arrested on 2 December 1821, he went to see the police in order to plead his fellow-delegate's case.[1][2] On 4 December 1821, he was himself arrested and detained and interrogated, apparently in some depth, by the widely feared (among anti-Austrian activists) investigating magistrate Antonio Salvotti. According to one source, it was on 13 December 1821 that, under interrogation, he made admissions which badly compromised himself and other patriots, including Federico Confalonieri: these he subsequently tried to deny the next day, pleading "madness" ("pazzo").[5] The trial that followed was conducted with "customary [Austrian] rigour and secrecy".[6] His trial and other processes were lengthy and, in the view of his most high-profile obituarist, dependent on false confessions drawn from the mouths of the unwary and uninformed.[3] These rituals appear to have come to an end during December 1823. Pallavicino Trivulzio was condemned to death: the sentence was commuted shortly afterwards to a twenty-year term of "harsh imprisonment" ("carcere duro").[7]

Prison

He spent the first and greater part of his incarceration in the Fortress of Spielberg (as it was known at the time) at Brno in Moravia, to which he was delivered on 24 February 1824. The northern wing of the prison had been newly adapted to incorporate a series of specially constructed cells for "state prisoners" (identified in Italian sources as Italian patriots). During the nineteenth century, helped in part by Pallavicino Trivulzio's own compelling written reports of his long incarceration there, Spielberg Castle acquired a level of infamy among the Italian public that twentieth century English speakers would impute to Alcatraz.[8] During his time imprisoned in Moravia he is reported to have suffered from a serious form of neurosis. His cellmates at Spielberg included Pietro Borsieri and Gaetano De Castillia. His attitude to at least some of his former revolutionary comrades became somewhat equivocal, to the extent that he undertook to provide fresh revelations against Confalonieri on condition that conditions governing his own life sentence might be ameliorated.[7] According to a surviving document dated 29 August 1832, he was by that time suffering from various serious gastric symptoms including "diarrhoea alternating with constipation" which subsequent commentators have diagnosed as consistent with acute chronic colitis. That year he was transferred to Gradisca.[8][9] By 1835, he had been transferred again, this time to Laibach (Lubiana / Ljubljana), and where his physical and mental condition are understood to have become "Precarious".[1][10]

"Amnesty in America" or "Confinement in Prague"

In Vienna the emperor died in March 1835 and his son, the well intention "Ferdinand der Gütige", came to the throne. It was a time for new beginnings, and Pallavicino Trivulzio, whose sentence still had more than five years to run, was offered early release. The imperial authorities made arrangements for him to be deported to America as part of a larger group of political detainees. However, it turned out that their illustrious prisoner did not wish to start a new life in America. There could, at this stage, be no question of returning him to Italy, where he might resume his former habit of fomenting separatism, so alternative arrangements were made for him to be "confined in Prague".[1][11] The intensity of his confinement is unclear, but during his five years in Prague he took the opportunity, in 1839, to marry Anna Koppmann, the daughter of the prison governor. The couple returned to Lombardy in 1840. Their daughter, another Anna, was born later that same year.[7][12][13]

They now settled at the family home in San Fiorano (Lodi) near Piacenza: for a few years little more was heard of Pallavicino Trivulzio. There is mention of his having been kept under low-level surveillance by the regional police department.[3]

1848

He returned to the political stage following the "Five Days of Milan", a brief but intense uprising on the city streets during March 1848 which led to the (temporary) expulsion of the Austrian garrison under Field Marshal Radetzky. Evidence of Pallavicino Trivulzio's attitude to these developments survives in the form of a painting by Giuseppe Molteni of his eight-year-old daughter dressed in the uniform that liberation fighters had adopted for the insurgency.[14][15] 1848 quickly became a year of revolutions in many of the Italian territories and states (and more widely across Europe), and in view of his earlier experiences following the (far more limited) anti-Austrian insurgencies of 1820/21 it is understandable that Pallavicino Trivulzio first move involved escaping (again) to Switzerland, from where he very soon moved on to Paris, where he sought to solicit support for the Risorgimento vision.[16] Following the restoration of the Austrian) order in August 1848 he moved to Turin, the capital of Piedmont-Sardinia which is positioned directly to the west of Lombardy. During the months when it seemed possible that Austria might capitulate or withdraw and that Italian unification might prove achievable in 1848, Pallavicino Trivulzio emerged as a "sincere and unqualified" advocate of a merger between Piedmont, Lombardy and Veneto even though integration into the Kingdom of Sardinia would confound his long-standing republican convictions.[1][17]

Turin exile

After 1848, as the Austrians sought to strengthen political and social control in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia, Pallavicino Trivulzio remained in Turin, resolved to use his still substantial fortune and his expanding network of contacts with French politicians and Italian exiles in Paris to progress the cause of unification. There were frequent trips to Paris to where, among others, Daniele Manin had escaped and now lived on in exile till his death in 1857.[1][3]

On 29 March 1849, not long after establishing his new home in Turin, he secured election to the lower house of the bicameral Sardinia-Piedmont parliament, representing at this stage a Genoa electoral district (Genova III). He continued to serve as a deputy (member of parliament) after the 1853 election, now representing a Turin electoral district (Torino II).[3] This period marked the start of a longer parliamentary career, but it does not appear that the parliament in Turin was the dominant centre of political power. Through the 1850s, Pallavicino Trivulzio exercised significant political influence in several different ways, but parliament was only one of various available platforms, and probably not the most effective. He was also generous in his financing of the cause, especially before 1853. He provided significant funding to publications such as L'Opinione, a relentlessly radical-liberal Turin-based daily newspaper.[1]

In Italian historiography the 1848 uprisings in Italy were (and continue to be) generally characterised as the First Italian War of Independence. Viewed in those terms the perceived outcome of those events, throughout the 1850s. was a brutal disappointment. During that decade, Pallavicino Trivulzio became increasingly active through his pen, raising his public profile by presenting himself as a martyr to the cause. That was easier after news came through, in 1853, that in Austrian-controlled Lombardy the government had seized his family lands.[18][19] "Spilbergo e Gradisca", the first volume of his prison memoirs was published a couple of years later.[20] He was strongly critical of Giuseppe Mazzini, the long-winded leading prophet of Italian liberation and unification. Pallavicino Trivulzio was very far from being alone, among the more impetuous of the risorgimento activists, in finding Mazzini's strategy for achieving the shared goal of unification lacking in practicality. Pallavicino Trivulzio continued to insist that taking the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont as the starting point for achieving unity was the only realistic option, because the kingdom was already equipped with constitutional arrangements and a formidable - if relatively small - army which, under the right circumstances, might be able to confront the Austrian military machine. There was also, in Turin, an available young king, already with a record of (cautious) supportiveness for the national cause. There were nevertheless a number of potential obstacles including, not leastly, powerful "municipal opposition" in Piedmont itself. With this in mind, he set up a meeting with Vincenzo Gioberti whose 1850 publication "Il Rinnovamento civile d’Italia" resonated closely with his own views in respect of the perceived timidity of the Piedmontese monarchy when it came to addressing what the two men saw as its risorgimento leadership role.[1]

He also approached Daniele Manin. an iconic figure since the events of 1848 when for five months her had served as President of the Republic of San Marco. Pallavicino Trivulzio did his best to persuade Manin to place himself at the head of a movement for "pragmatic republicans" willing to compromise with monarchists in order to progress the higher goal of national independence. Once he had succeeded in persuading Manin to accept the proposal for a public launch of a "national party", Pallavicino Trivulzio firmly identified himself as "second in command", recognising the superior political capabilities of the exiled Venetian. Manin's health was failing by this time, and when he died in September 1857 the new party had only existed for slightly more than one year. Despite Pallavicino Trivulzio presenting himself as Manin's loyal lieutenant, the party leadership during 1856/57 was probably a less unequal responsibility than he had anticipated. He found himself repeatedly pressing Manin to intervene in political debates, especially when it came to speaking out to thwart those seeking to have Lucien Murat, "the fat pretender" installed as "King of Naples".[1][21] Pallavicino Trivulzio and Manin continued to share an acute appreciation of the need to focus constantly on listening to and influencing public opinion across Italy and internationally when it came to their risorgimento goals. Pallavicino Trivulzio was conspicuously public in his defence of Manin after his political comrade drew criticism for an article he had published in The Times of London on 25 May 1856 in which he had accused Mazzini of providing a rationale for political murder ("... teorizzare l’omicidio politico").[1][22]

During the 1850s, and especially during the first part of the decade, Pallavicino Trivulzio's relations with the political establishment in Piedmont (and with the government) were far from easy. As a member of parliament throughout the period, he was often to be found siding with the opposition. He spoke out against Piedmontese military intervention alongside the Ottoman Empire, the French and the British in the 1855 Crimean War, though after the Congress of Paris he did grudgingly admit to having at least partially modified his opinion of Cavour whom he had hitherto condemned icily as "piemontesissimo" (loosely, "too Piedmontese").[3][23] It was the kingdom's first minister Cavour who introduced him in 1856 to Giuseppe La Farina, an exceptionally able organiser, who tried to give structure to the "National Party" which Pallavicino Trivulzio was setting up with Manin, and which was transformed, rebranded and relaunched, formally at Turin in August 1857, "Società nazionale italiana" (Italian National Society), apparently in response to a casual "suggestion" the previous year from Cavour. La Farina became the first secretary of the "Società nazionale italiana" while Pallavicino Trivulzio, following Manin's death, took his place as "president" (leader). In reality this enabled Pallavicino Trivulzio to serve as the organisation's indefatigable propagandist-networker, also financing La Farina's newspaper, "Piccolo Corriere d’Italia". Meanwhile, La Farina's involvement as its secretary enabled the "Società nazionale" to retain an underlying air of moderation which may very well have been what Cavour had been hoping to achieve when he had introduced the two men in the first place.[1][24] When it came to networking, Pallavicino Trivulzio's most important achievement was his success in making an ally of Garibaldi, who became a member of the "Società nazionale", thereby greatly broadening its popular appeal. Shortly after first meeting Cavour at the end of 1858, Garibaldi indeed became an honorary vice-president of the "Società nazionale".[25][26]

1859

During 1858/59 the "Società nazionale italiana" gained traction across the states and territories of Italy, helped by a more focused organisational structure implemented by La Farina, supportive endorsement from Garibaldi, a more collaborative approach from Cavour (and the government in Piedmont), and a period of internal crisis within the Mazzinian Action Party. Nevertheless, once the Second War of Independence broke out during the early summer of 1859, Pallavicino Trivulzio concluded that the "Società"'s work was done, and he declared its dissolved. Taking a slightly longer view, he may have been right. Nevertheless, after three months of brutish fighting the Armistice of Vilafranca was concluded towards the end of July 1859 and La Farina brought the "Società" back to life in defiance of the views of its former president. La Farina himself, following its reconstitution, took on its presidency himself on 20 October 1859. Pallavicino Trivulzio was irritated by these developments, but he had, in his own mind, already moved on: for him the "Società nazionale italiana" had become nothing more than a tool firmly in the hands off Cavour. He had nothing more to do with the "Società", which was definitively dissolved in 1862.[1][24][27]

Senator

Pallavicino Trivulzio's relationship with Cavour had never become an entirely easy one, and he saw his nomination to the Senate of the Kingdom of Italy on 29 February 1860 as a shamelessly "piemontesissimo" move to distance him from the political mainstream. Pallavicino Trivulzio nevertheless took his senatorial oath on 2 April 1860 and his senatorial membership was confirmed on 11 April 1860. One of his first moves as a senator was to speak out in savage condemnation of the transfer of what had been left after 1792 of the old County of Nice and Duchy of Savoy to France in 1860. (These concessions were necessary to fulfil the terms of a highly secret - at the time - agreement concluded in 1858 under which Cavour had secured a guarantee of military support from the French emperor in what became known as the Second Italian War of Independence.)[1][3][28]

Turin's man and Garibaldi's friend in Naples

Although the war that secured independence and unification was abruptly terminated in July 1859 by means of the Armistice of Vilafranca, there was at that point much more negotiation to be concluded, and it would only be in March 1861 that Italian unification would be formally proclaimed. Much of the unfinished business involved Giuseppe Garibaldi who, despite being a staunch ally in respect of the twin goals of liberation and unification, had his own strategy and indeed his own preconceptions on what sort of a united Italy would and should result from the military phase of the campaign. In September 1860 Giorgio Pallavicino was summoned by Garibaldi to Naples, where he was appointed as one of two "prodittatore" (loosely, but in some ways misleadingly, "pro-dictator") by Garibaldi through means of a decree issued in the name of His Majesty King Victor Emmanuel. The appointment of his friend Giorgio Pallavicino to this position does indeed appear to have been implemented by Garibaldi in order to strengthen his standing with King Victor Emmanuel of Piedmont, with whom it would be necessary to collaborate if unification was to move ahead. Almost as soon as he had been appointed, Giorgio Pallavicino, was sent back on a mission to Piedmont with instructions to persuade the king to secure the resignation of the Cavour government. It seems unlikely that Pallavicino Trivulzio himself was entirely convinced as to the wisdom of the mission. The king, in any event, was not persuaded.[1]

On returning to Naples Pallavicino Trivulzio was immediately caught up in a vigorous dispute with Francesco Crispi and other "republican-democrats" taking their lead from Crispi, over the future progress of the unification project. Garibaldi's original, never very clearly spelled out vision had probably been that Italian unification should be achieved through a constantly expanding popular insurrection. That vision was evidently shared by his newly appointed "secretary of state", Francesco Crispi. Crispi was an uncompromising republican to whom the idea of anything involving monarchy was an anathema. Pallavicino Trivulzio, meanwhile, having returned to Naples. immediately emerged, slightly implausibly, as Cavour's man within Garibaldi's inner circle. Cavour was instinctively opposed to popular insurrection under almost any circumstances, and the idea of backing a popular insurrection that involved capturing Rome looked particularly imprudent, given that Rome was protected by a significant force of French troops. The terms secured from the Austrians the previous year in the Armistice of Vilafranca had only been possible because of the highly effective military alliance between Piedmont and France. Cavour's relatively cautious objectives and expectations back at the beginning of 1859 had probably been limited to the removal of Austrian hegemony from northern and central Italy, and the creation in their place of two kingdoms ruled respectively from Turin and Florence, while a small territory surrounding Rome, roughly equivalent in size to Corsica, should remain under papal control. If the king were to agree with Garibaldi, after Garibaldi's conquests in the south during 1860, that the territories conquered by Garibaldi should be added to a single Italian kingdom, then Cavour would insist - and did - that this could only be achieved through some form of agreed annexation. The revolutionary spirit of republicanism was not dead: popular insurrection had no place on the agenda of a First Minister who served in king. An added source of tension came from the fact that Garibaldi, like everyone else outside the immediate circle of Victor Emanuel, had been unaware of the (probably unwritten) agreement between the French emperor and Cavour whereby the County of Nice was unexpectedly transferred to France as part of the price for French military support against Austria. Garibaldi had been born in Nice and never forgave Cavour for "sacrificing" the city of his birth. Back in Naples, Pallavicino Trivulzio made clear his belief that Francesco Crispi was completely unsuitable to be "secretary of state" of anywhere. Garibaldi initially equivocated over this (and other) matters. An even more pressing decision was needed over how agreement should be demonstrably secured for the annexation to the rest of Italy of Naples and Sicily, over which Garibaldi had never expressed any wish to retain permanent control. Crispi proposed the establishment and convening of a parliament-style assembly in Naples and/or Palermo to determine conditions under which the "southern provinces" might be annexed to the new Italian state on the other side of Rome. Pallavicino Trivulzio saw the creation of such am assembly as a certain recipe for civil war. It was with this in mind that he addressed an open letter to Giuseppe Mazzini, who had turned up in Naples a few months earlier, urging that Mazzini leave Naples, because he considered Mazzini's presence dangerously divisive. Rather than creating some sort of constitutional assembly to endorse the annexation of Naples and Sicily to the rest of Italy, Pallavicino Trivulzio favoured a referendum of the people. In this he was supported in Naples by the National Guard and by a succession of powerful street demonstrations. Garibaldi remained indecisive, and delegated a final decision to his two "prodictators", Pallavicino Trivulzio in Naples and Antonio Mordini in Sicily. Crispi continued to argue for a constitutional assembly. Pallavicino Trivulzio's youthful impulsiveness very quickly resurfaced as statesmanlike decisiveness. At the start of October 1860, Pallavicino Trivulzio went ahead and announced a unification referendum to take place across the "Kingdom of Naples" in just three weeks' time, on 21 October 1860. Garibaldi and Mordini found themselves unable to resist the pressures to follow suit in respect of Sicily.[1][29]

Pallavicino Trivulzio formulated the referendum question himself: "Do the people want a single indivisible Italy with Victor Emmanuel and his legitimate descendants as their constitutional king?"[lower-alpha 1] The referendum result was an overwhelming victory for unification, for monarchy, and for Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio. Camillo Cavour, who had made no secret over his reservations over the king's appointment of Pallavicino Trivulzio's posting to Naples, was favourably impressive with "Prodictator Pallavicino's" decisiveness and sureness of judgement when those around him had dithered. He sent Pallavicino a telegramme: "Italy rejoices over the splendid outcome of the plebiscite, which is largely down to your wisdom, decisiveness and patriotism. Thus she acquired new and glorious titles which thrill the entire nation".[lower-alpha 2] Cavour also let it be known that it was at his own recommendation that the king was awarding him the Collar of the Most Holy Annunciation, a much coveted honour, conferred on Pallavicino Trivulzio on 9 November 1860.[1][3]

Fractious senator

Relations between Garibaldi and Pallavicino Trivulzio may have become frayed at the end of 1860 during the aftermath of the October referendum, and during 1861 Garibaldi's revolutionary aspirations became concentrated on the unfolding American Civil War. 1862 saw something of a reconciliation. During 1862 Urbano Rattazzi, nominated Pallavicino Trivulzio as prefect of Palermo. It was not a happy choice. Garibaldi was on the march again, and the city streets were seething with "serious disorder".[3] Pallavicino Trivulzio evidently had no idea as to how he might prevent the situation from getting worse, and his loyalty to his friend "General Garibaldi" did not enable him to restrain Garibaldi from embarking on another messy (and, it turned out, this time unsuccessful) attempt to integrate the remaining Papal States into Italy (which, as before, risked a destructive war with France, still Italy's only true ally among the European "powers"). Pallavicino Trivulzio reacted to the unrest on the streets by calling on everyone the cooperate with the "Garibaldian" Action Party, while blaming the rising tide of "public order difficulties" on plotting "Murattiani", separatists and Borbinici revanchists. Pallavicino Trivulzio remained active in the Palermo post for slightly more than three months, between 16 April and 25 July 1862.[30] Despite his enforced resignation from the Palermo prefecture, Pallavicino Trivulzio held on to the vice-presidency of the senate, to which he had been appointed on 3 February 1861, till 21 May 1863.[3]

In 1864 he delivered a harshly critical speech in the senate, opposing the so-called September Convention, an agreement concluded between the governments of France and Italy whereby all French troops would be withdrawn from the Papal States within two years and Italy would guarantee the frontiers of the Papal States as constituted at the time. There were various conditions, and at least one protocol kept secret when the convention was published, binding Italy to move its capital away from Turin. (The next year it emerged that Italy's new capital would be established at Florence.) Pallavicino Trivulzio, in his senate speech, complained that the "convention of 15 September" amounted to a surrender to the wishes of France's Emperor Napoleon, and signalled a policy of renouncing Italian ambitions. In 1867, in a public argument with Prime Minister Ricasoli, Subsequently he repeated his critique - which Garibaldi himself could surely not have expressed any more firmly - notably during the aftermath of the Battle of Custoza, which the Italian army had lost (though the country suffered no lasting disadvantage, thanks to the Prussian victory at Königgrätz a couple of weeks later).[1][31]

Although senators were appointed for life, after the end of 1864 Pallavicino Trivulzio ceased to be an active parliamentarian, while remaining among the supporters of the incorporation of the Papal States surrounding and including Rome into the Italian kingdom. The outcome of the Battle of Mentana, in which a volunteer army led by Garibaldi was defeated by an army of French-Papal troops in November 1867, appeared to put an end to that dream for the foreseeable future. Just three years later, however, with the French military machine otherwise engaged, the Italian army seized the opportunity. Rome was over-run and became the capital of Italy, leaving just the Vatican City unconquered. For more than a generation, till 1929, the "Roman Question", involving some sort of agreement as to the division of powers and lands between the papacy and the Italian government, remained unresolved, and the Popes remained effectively trapped inside the confines of their residual city centre territory. For Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio, and for many other traditionalist risorgimento patriots who had given over their lives to the unification project, 1870 would be seen as something of a missed opportunity.[1]

Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio lived out his final years out of the public spotlight, increasingly detained at his home by the infirmities of old age. As an old man he returned to the republican idealism of his youth, becoming disenchanted with the monarchy and its apparently bottomless appetite for money and privilege. However, his republicanism remained something defined more by his classicists' rhetoric, rather than a concrete political aspiration backed by a cogent strategy. He became preoccupied by the advance of socialism, especially after Garibaldi came out in support of "the international" as the inevitable way of the future. For Pallavicino Trivulzio that was something which negated the very concept of a homeland. He did not deny the existence of social problems, much exacerbated by industrialisation and galloping urbanisation during the second half of the nineteenth century. But he believed that the solutions were to be found in education and charitable activities, backed by the urgent need to extend voting rights.[1]

He died at Genestrelle (Casteggio) near Pavia on 4 August 1878.[1]

Public recognition (selection)

Notes

- "Il popolo vuole l’Italia una e indivisibile con Vittorio Emmanuele Re costituzionale e suoi legittimi discendenti?"[3]

- "L’Italia esulta per lo splendido risultato del plebiscito, che al suo senno, alla sua fermezza, e al suo patriottismo è in gran parte dovuto. Ella si è acquistato così nuovi e gloriosi titoli alla riconoscenza della nazione".[3]

References

- Ester De Fort (2014). "Pallavicino Trivulzio, Giorgio Guido". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Atto Vannucci. Gaetano Castillia, Giorgio Pallavicino, Pietro Bonsieri e altre vittime dell'Austria. pp. 255–266. ISBN 978-1437155273. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Sebastiano Tecchio (4 February 1879). "Pallavicino Trivulzio Giorgio .... Atti parlamentari - Commemorazione". Indice dell'Attività Parlamentare. L'Archivio storico del Senato, Roma. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Luigi Ambrosoli (1982). "Confalonieri, Federico. - Nacque a Milano il 6 ott. 1785 da Vitaliano, di famiglia comitale assai facoltosa per le estese proprietà terriere ..." Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Werner Manica (9 March 2021). Carbonari .... Altri importanti Carbonari, rivoluzionari e patrioti condannati da Salvotti. ISBN 9783346389367. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Villari, Luigi (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 897–898.

- Mario Menghini (1935). "Pallavicino Trivùlzio, Giorgio Guido, marchese". Enciclopedia Italiana. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Charles Klopp (25 December 1999). The Spielberg: Concealment and refutation. pp. 38–66. ISBN 978-0802044563. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Dino Felisati (January 2011). La Vita allo Spielberg. ISBN 978-8856837834. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Giuseppe Stefani (January 1958). Confalinieri sulla via dell'esilio - III. pp. 111, 103–146. ISBN 978-8884988799. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Matteo Turconi Sormani (3 December 2015). Pallavicino Trivulzio. pp. 189–190. ISBN 9788854187146. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "La Villa Pallavicino". fai a genestrello.

- "Villa dei Coardi di Carpeneto Mazza" (PDF). Art auction catalogue. Wannenes, Genova. September 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Giuseppe Molteni. "Giuseppe Molteni. 1800-1867. Portrait of the young marquise Anna Pallavicino Trivulzio. 1848 oil painting on canvas". Getty Images, Seattle WA. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- "Giuseppe Molteni. Ritratto della marchesina Anna Pallavicino Trivulzio con la divisa della 5 Giornate. 1848. Olio su tela 126x102 .... Collezione privata". Exhibition review .... "La mostra 1861. I pittori del Risorgimento, che si apre a Roma, alle Scuderie del Quirinale il 6 ottobre e si chiude nell'anno che celebra l'Unita d'Italia ....". InItalia online. 1861. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Andrea Venti (2010). Conspiratori, agenti e servatori segreti. Le biografie. pp. 392–393. ISBN 978-8856504200. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Pietro Giovanni Trinicanato (2018). "Il decennio di preparzione deglio esuli Italiani in Francia" (PDF). Alle origini del liberalismo moderato: la Società Nazionale italiana nel decennio di preparazione. Universita degli studi di Milano & Université Paris-Est. pp. 57, 38–76. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio (1862). "Io dubitava se dovessi, o no, rispondere a Messer Boggio. E che?..." letter reproduced in "Risposta di Giorgio Pallayicino al Deputato Pier Carlo Boggio" (seconda edizione). pp. 16, 15–32. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Giacomo Girardi. "Il sequestrato: gli emigrati veneti e la repressione austriaca .... Gli emigrati del 1853-1854 /" (PDF). I beni degli esuli - I sequestri austriaci in Veneto tra controllo politico e prassi burocratica (1848-1861). Università degli Studi di Milano. pp. 210–231. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio. Spilbergo e Gradisca scene del carcere duro in Austria, estratte dalle memorie di Giorgio Pallavicino 1856 (reprinted in 2019). Stamperia dell'Unione Tip.-Editrice, Torino.

- "Affairs in France; The Difficulties among the Free Masons Prince Lucien Murat and his Proceedings The Election of Prince Napoleon as Grand Master". The New York Times. 17 June 1861. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Denis Mack Smith (1968). Mazzini and national society. p. 214. ISBN 978-0333438084. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Giuseppe Monsagrati (10 November 2011). Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio. pp. 307–310. ISBN 9788849219746. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Mario Menghini (1934). "Nazionale, Società". Enciclopedia Italiana. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Vita di G. Garibaldi, p. 25, G. Barbèra, 1860

- "La Società Nazionale". Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- "Società nazionale". Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- Antonio Ciano (17 June 2016). "Come l'infame Cavour, traditore della patria, vendette La contea di Nizza e la Savoia". Il 24 Marzo del 1860 il “grande” statista Cavour diventò ufficialmente traditore della Patria: vendette la moglie al diavolo, anzi peggio, regalò alla Francia due province italianissime, parte del sacro suolo italiano, ma soprattutto mercificò i cittadini di quei territori. Pontelandolfo News (BN). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- Angelo Grimaldi (2019). "Il terzo governo della dittatura Garibaldina". Carmicia Rossa - Periodico dell'Associazione Nationale Veterani a Reduci Garibaldini. Associazione Nazionale Veterani e Reduci Garibaldini. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- Rosanna Roccia ed (13 April 2015). Caro Depretis (A Agostino Depretis .... editor's footnote elucidating the contents of a letter). pp. 42, 40–45. ISBN 9788849297133. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - "Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio, La Convenzione del 15 settembre 1864: discorso del senatore Giorgio Pallavicino Trivulzio pronunciato nella tornata del 6 dicembre 1864, con appendice". Dicembre 1864: una legge per Firenze Capitale. Annali di Storia di Firenze. Retrieved 24 March 2022.