Gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the generation of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms.[1] In vertebrates, gluconeogenesis occurs mainly in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the cortex of the kidneys. It is one of two primary mechanisms – the other being degradation of glycogen (glycogenolysis) – used by humans and many other animals to maintain blood sugar levels, avoiding low levels (hypoglycemia).[2] In ruminants, because dietary carbohydrates tend to be metabolized by rumen organisms, gluconeogenesis occurs regardless of fasting, low-carbohydrate diets, exercise, etc.[3] In many other animals, the process occurs during periods of fasting, starvation, low-carbohydrate diets, or intense exercise.

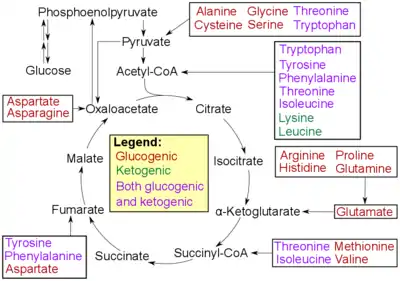

In humans, substrates for gluconeogenesis may come from any non-carbohydrate sources that can be converted to pyruvate or intermediates of glycolysis (see figure). For the breakdown of proteins, these substrates include glucogenic amino acids (although not ketogenic amino acids); from breakdown of lipids (such as triglycerides), they include glycerol, odd-chain fatty acids (although not even-chain fatty acids, see below); and from other parts of metabolism that includes lactate from the Cori cycle. Under conditions of prolonged fasting, acetone derived from ketone bodies can also serve as a substrate, providing a pathway from fatty acids to glucose.[4] Although most gluconeogenesis occurs in the liver, the relative contribution of gluconeogenesis by the kidney is increased in diabetes and prolonged fasting.[5]

The gluconeogenesis pathway is highly endergonic until it is coupled to the hydrolysis of ATP or GTP, effectively making the process exergonic. For example, the pathway leading from pyruvate to glucose-6-phosphate requires 4 molecules of ATP and 2 molecules of GTP to proceed spontaneously. These ATPs are supplied from fatty acid catabolism via beta oxidation.[6]

Precursors

- Glucogenic amino acids have this ability

- Ketogenic amino acids do not. These products may still be used for ketogenesis or lipid synthesis.

- Some amino acids are catabolized into both glucogenic and ketogenic products.

In humans the main gluconeogenic precursors are lactate, glycerol (which is a part of the triglyceride molecule), alanine and glutamine. Altogether, they account for over 90% of the overall gluconeogenesis.[8] Other glucogenic amino acids and all citric acid cycle intermediates (through conversion to oxaloacetate) can also function as substrates for gluconeogenesis.[9] Generally, human consumption of gluconeogenic substrates in food does not result in increased gluconeogenesis.[10]

In ruminants, propionate is the principal gluconeogenic substrate.[3][11] In nonruminants, including human beings, propionate arises from the β-oxidation of odd-chain and branched-chain fatty acids, and is a (relatively minor) substrate for gluconeogenesis.[12][13]

Lactate is transported back to the liver where it is converted into pyruvate by the Cori cycle using the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase. Pyruvate, the first designated substrate of the gluconeogenic pathway, can then be used to generate glucose.[9] Transamination or deamination of amino acids facilitates entering of their carbon skeleton into the cycle directly (as pyruvate or oxaloacetate), or indirectly via the citric acid cycle. The contribution of Cori cycle lactate to overall glucose production increases with fasting duration.[14] Specifically, after 12, 20, and 40 hours of fasting by human volunteers, the contribution of Cori cycle lactate to gluconeogenesis was 41%, 71%, and 92%, respectively.[14]

Whether even-chain fatty acids can be converted into glucose in animals has been a longstanding question in biochemistry.[15] Odd-chain fatty acids can be oxidized to yield acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA, the latter serving as a precursor to succinyl-CoA, which can be converted to oxaloacetate and enter into gluconeogenesis. In contrast, even-chain fatty acids are oxidized to yield only acetyl-CoA, whose entry into gluconeogenesis requires the presence of a glyoxylate cycle (also known as glyoxylate shunt) to produce four-carbon dicarboxylic acid precursors.[9] The glyoxylate shunt comprises two enzymes, malate synthase and isocitrate lyase, and is present in fungi, plants, and bacteria. Despite some reports of glyoxylate shunt enzymatic activities detected in animal tissues, genes encoding both enzymatic functions have only been found in nematodes, in which they exist as a single bi-functional enzyme.[16][17] Genes coding for malate synthase alone (but not isocitrate lyase) have been identified in other animals including arthropods, echinoderms, and even some vertebrates. Mammals found to possess the malate synthase gene include monotremes (platypus) and marsupials (opossum), but not placental mammals.[17]

The existence of the glyoxylate cycle in humans has not been established, and it is widely held that fatty acids cannot be converted to glucose in humans directly. Carbon-14 has been shown to end up in glucose when it is supplied in fatty acids,[18] but this can be expected from the incorporation of labelled atoms derived from acetyl-CoA into citric acid cycle intermediates which are interchangeable with those derived from other physiological sources, such as glucogenic amino acids.[15] In the absence of other glucogenic sources, the 2-carbon acetyl-CoA derived from the oxidation of fatty acids cannot produce a net yield of glucose via the citric acid cycle, since an equivalent two carbon atoms are released as carbon dioxide during the cycle. During ketosis, however, acetyl-CoA from fatty acids yields ketone bodies, including acetone, and up to ~60% of acetone may be oxidized in the liver to the pyruvate precursors acetol and methylglyoxal.[19][4] Thus ketone bodies derived from fatty acids could account for up to 11% of gluconeogenesis during starvation. Catabolism of fatty acids also produces energy in the form of ATP that is necessary for the gluconeogenesis pathway.

Location

In mammals, gluconeogenesis has been believed to be restricted to the liver,[20] the kidney,[20] the intestine,[21] and muscle,[22] but recent evidence indicates gluconeogenesis occurring in astrocytes of the brain.[23] These organs use somewhat different gluconeogenic precursors. The liver preferentially uses lactate, glycerol, and glucogenic amino acids (especially alanine) while the kidney preferentially uses lactate, glutamine and glycerol.[24][8] Lactate from the Cori cycle is quantitatively the largest source of substrate for gluconeogenesis, especially for the kidney.[8] The liver uses both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis to produce glucose, whereas the kidney only uses gluconeogenesis.[8] After a meal, the liver shifts to glycogen synthesis, whereas the kidney increases gluconeogenesis.[10] The intestine uses mostly glutamine and glycerol.[21]

Propionate is the principal substrate for gluconeogenesis in the ruminant liver, and the ruminant liver may make increased use of gluconeogenic amino acids (e.g., alanine) when glucose demand is increased.[25] The capacity of liver cells to use lactate for gluconeogenesis declines from the preruminant stage to the ruminant stage in calves and lambs.[26] In sheep kidney tissue, very high rates of gluconeogenesis from propionate have been observed.[26]

In all species, the formation of oxaloacetate from pyruvate and TCA cycle intermediates is restricted to the mitochondrion, and the enzymes that convert Phosphoenolpyruvic acid (PEP) to glucose-6-phosphate are found in the cytosol.[27] The location of the enzyme that links these two parts of gluconeogenesis by converting oxaloacetate to PEP – PEP carboxykinase (PEPCK) – is variable by species: it can be found entirely within the mitochondria, entirely within the cytosol, or dispersed evenly between the two, as it is in humans.[27] Transport of PEP across the mitochondrial membrane is accomplished by dedicated transport proteins; however no such proteins exist for oxaloacetate.[27] Therefore, in species that lack intra-mitochondrial PEPCK, oxaloacetate must be converted into malate or aspartate, exported from the mitochondrion, and converted back into oxaloacetate in order to allow gluconeogenesis to continue.[27]

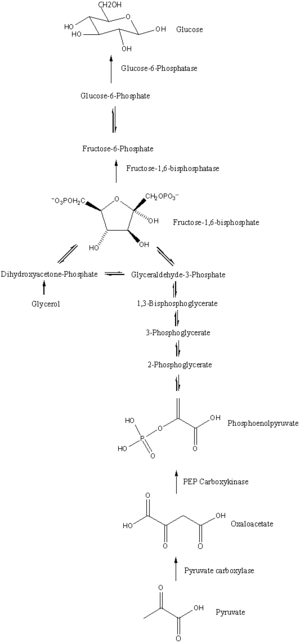

Pathway

Gluconeogenesis is a pathway consisting of a series of eleven enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The pathway will begin in either the liver or kidney, in the mitochondria or cytoplasm of those cells, this being dependent on the substrate being used. Many of the reactions are the reverse of steps found in glycolysis.

- Gluconeogenesis begins in the mitochondria with the formation of oxaloacetate by the carboxylation of pyruvate. This reaction also requires one molecule of ATP, and is catalyzed by pyruvate carboxylase. This enzyme is stimulated by high levels of acetyl-CoA (produced in β-oxidation in the liver) and inhibited by high levels of ADP and glucose.

- Oxaloacetate is reduced to malate using NADH, a step required for its transportation out of the mitochondria.

- Malate is oxidized to oxaloacetate using NAD+ in the cytosol, where the remaining steps of gluconeogenesis take place.

- Oxaloacetate is decarboxylated and then phosphorylated to form phosphoenolpyruvate using the enzyme PEPCK. A molecule of GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP during this reaction.

- The next steps in the reaction are the same as reversed glycolysis. However, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase converts fructose 1,6-bisphosphate to fructose 6-phosphate, using one water molecule and releasing one phosphate (in glycolysis, phosphofructokinase 1 converts F6P and ATP to F1,6BP and ADP). This is also the rate-limiting step of gluconeogenesis.

- Glucose-6-phosphate is formed from fructose 6-phosphate by phosphoglucoisomerase (the reverse of step 2 in glycolysis). Glucose-6-phosphate can be used in other metabolic pathways or dephosphorylated to free glucose. Whereas free glucose can easily diffuse in and out of the cell, the phosphorylated form (glucose-6-phosphate) is locked in the cell, a mechanism by which intracellular glucose levels are controlled by cells.

- The final gluconeogenesis, the formation of glucose, occurs in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, where glucose-6-phosphate is hydrolyzed by glucose-6-phosphatase to produce glucose and release an inorganic phosphate. Like two steps prior, this step is not a simple reversal of glycolysis, in which hexokinase catalyzes the conversion of glucose and ATP into G6P and ADP. Glucose is shuttled into the cytoplasm by glucose transporters located in the endoplasmic reticulum's membrane.

| Metabolism of common monosaccharides, including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, glycogenesis and glycogenolysis |

|---|

|

Regulation

While most steps in gluconeogenesis are the reverse of those found in glycolysis, three regulated and strongly endergonic reactions are replaced with more kinetically favorable reactions. Hexokinase/glucokinase, phosphofructokinase, and pyruvate kinase enzymes of glycolysis are replaced with glucose-6-phosphatase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and PEP carboxykinase/pyruvate carboxylase. These enzymes are typically regulated by similar molecules, but with opposite results. For example, acetyl CoA and citrate activate gluconeogenesis enzymes (pyruvate carboxylase and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, respectively), while at the same time inhibiting the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase. This system of reciprocal control allow glycolysis and gluconeogenesis to inhibit each other and prevents a futile cycle of synthesizing glucose to only break it down. Pyruvate kinase can be also bypassed by 86 pathways[28] not related to gluconeogenesis, for the purpose of forming pyruvate and subsequently lactate; some of these pathways use carbon atoms originated from glucose.

The majority of the enzymes responsible for gluconeogenesis are found in the cytosol; the exceptions are mitochondrial pyruvate carboxylase and, in animals, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. The latter exists as an isozyme located in both the mitochondrion and the cytosol.[29] The rate of gluconeogenesis is ultimately controlled by the action of a key enzyme, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, which is also regulated through signal transduction by cAMP and its phosphorylation.

Global control of gluconeogenesis is mediated by glucagon (released when blood glucose is low); it triggers phosphorylation of enzymes and regulatory proteins by Protein Kinase A (a cyclic AMP regulated kinase) resulting in inhibition of glycolysis and stimulation of gluconeogenesis. Insulin counteracts glucagon by inhibiting gluconeogenesis. Type 2 diabetes is marked by excess glucagon and insulin resistance from the body.[30] Insulin can no longer inhibit the gene expression of enzymes such as PEPCK which leads to increased levels of hyperglycemia in the body.[31] The anti-diabetic drug metformin reduces blood glucose primarily through inhibition of gluconeogenesis, overcoming the failure of insulin to inhibit gluconeogenesis due to insulin resistance.[32]

Studies have shown that the absence of hepatic glucose production has no major effect on the control of fasting plasma glucose concentration. Compensatory induction of gluconeogenesis occurs in the kidneys and intestine, driven by glucagon, glucocorticoids, and acidosis.[33]

Insulin resistance

In the liver, the FOX protein FOXO6 normally promotes gluconeogenesis in the fasted state, but insulin blocks FOXO6 upon feeding.[34] In a condition of insulin resistance, insulin fails to block FOXO6 resulting in continued gluconeogenesis even upon feeding, resulting in high blood glucose (hyperglycemia).[34]

Insulin resistance is a common feature of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. For this reason gluconeogenesis is a target of therapy for type 2 diabetes, such as the antidiabetic drug metformin, which inhibits gluconeogenic glucose formation, and stimulates glucose uptake by cells.[35]

Origins

Gluconeogenesis is considered one of the most ancient anabolic pathways and is likely to have been exhibited in the last universal common ancestor.[36] Rafael F. Say and Georg Fuchs stated in 2010 that "all archaeal groups as well as the deeply branching bacterial lineages contain a bifunctional fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) aldolase/phosphatase with both FBP aldolase and FBP phosphatase activity. This enzyme is missing in most other Bacteria and in Eukaryota, and is heat-stabile even in mesophilic marine Crenarchaeota". It is proposed that fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase/phosphatase was an ancestral gluconeogenic enzyme and had preceded glycolysis.[37] But the chemical mechanisms between gluconeogenesis and glycolysis, whether it is anabolic or catabolic, are similar, suggesting they both originated at the same time. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate is shown to be nonenzymatically synthesized continuously within a freezing solution. The synthesis is accelerated in the presence of amino acids such as glycine and lysine implying that the first anabolic enzymes were amino acids. The prebiotic reactions in gluconeogenesis can also proceed nonenzymatically at dehydration-desiccation cycles. Such chemistry could have occurred in hydrothermal environments, including temperature gradients and cycling of freezing and thawing. Mineral surfaces might have played a role in the phosphorylation of metabolic intermediates from gluconeogenesis and have to been shown to produce tetrose, hexose phosphates, and pentose from formaldehyde, glyceraldehyde, and glycolaldehyde.[38][39][40]

See also

References

- Nelson DL, Cox MM (2000). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. USA: Worth Publishers. p. 724. ISBN 978-1-57259-153-0.

- Silva P. "The Chemical Logic Behind Gluconeogenesis". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- Beitz DC (2004). "Carbohydrate metabolism.". In Reese WO (ed.). Dukes' Physiology of Domestic Animals (12th ed.). Cornell Univ. Press. pp. 501–15. ISBN 978-0801442384.

- Kaleta C, de Figueiredo LF, Werner S, Guthke R, Ristow M, Schuster S (July 2011). "In silico evidence for gluconeogenesis from fatty acids in humans". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (7): e1002116. Bibcode:2011PLSCB...7E2116K. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002116. PMC 3140964. PMID 21814506.

- Swe MT, Pongchaidecha A, Chatsudthipong V, Chattipakorn N, Lungkaphin A (June 2019). "Molecular signaling mechanisms of renal gluconeogenesis in nondiabetic and diabetic conditions". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 234 (6): 8134–8151. doi:10.1002/jcp.27598. PMID 30370538. S2CID 53097552.

- Rodwell V (2015). Harper's illustrated Biochemistry, 30th edition. USA: McGraw Hill. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-07-182537-5.

- Ferrier DR, Champe PC, Harvey RA (1 August 2004). "20. Amino Acid Degradation and Synthesis". Biochemistry. Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2265-0.

- Gerich JE, Meyer C, Woerle HJ, Stumvoll M (February 2001). "Renal gluconeogenesis: its importance in human glucose homeostasis". Diabetes Care. 24 (2): 382–91. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.2.382. PMID 11213896.

- Garrett RH, Grisham CM (2002). Principles of Biochemistry with a Human Focus. USA: Brooks/Cole, Thomson Learning. pp. 578, 585. ISBN 978-0-03-097369-7.

- Nuttall FQ, Ngo A, Gannon MC (September 2008). "Regulation of hepatic glucose production and the role of gluconeogenesis in humans: is the rate of gluconeogenesis constant?". Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 24 (6): 438–458. doi:10.1002/dmrr.863. PMID 18561209. S2CID 24330397.

- Van Soest PJ (1994). Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant (2nd ed.). Cornell Univ. Press. ISBN 978-1501732355.

- Rodwell VW, Bender DA, Botham KM, Kennelly PJ, Weil PA (2018). Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry (31st ed.). McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- Baynes J, Dominiczak M (2014). Medical Biochemistry (4th ed.). Elsevier.

- Katz J, Tayek JA (September 1998). "Gluconeogenesis and the Cori cycle in 12-, 20-, and 40-h-fasted humans". The American Journal of Physiology. 275 (3): E537–42. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.3.E537. PMID 9725823.

- de Figueiredo LF, Schuster S, Kaleta C, Fell DA (January 2009). "Can sugars be produced from fatty acids? A test case for pathway analysis tools". Bioinformatics. 25 (1): 152–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn621. PMID 19117076.

- Liu F, Thatcher JD, Barral JM, Epstein HF (June 1995). "Bifunctional glyoxylate cycle protein of Caenorhabditis elegans: a developmentally regulated protein of intestine and muscle". Developmental Biology. 169 (2): 399–414. doi:10.1006/dbio.1995.1156. PMID 7781887.

- Kondrashov FA, Koonin EV, Morgunov IG, Finogenova TV, Kondrashova MN (October 2006). "Evolution of glyoxylate cycle enzymes in Metazoa: evidence of multiple horizontal transfer events and pseudogene formation". Biology Direct. 1: 31. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-31. PMC 1630690. PMID 17059607.

- Weinman EO, Strisower EH, Chaikoff IL (April 1957). "Conversion of fatty acids to carbohydrate; application of isotopes to this problem and role of the Krebs cycle as a synthetic pathway". Physiological Reviews. 37 (2): 252–72. doi:10.1152/physrev.1957.37.2.252. PMID 13441426.

- Reichard GA, Haff AC, Skutches CL, Paul P, Holroyde CP, Owen OE (April 1979). "Plasma acetone metabolism in the fasting human". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 63 (4): 619–26. doi:10.1172/JCI109344. PMC 371996. PMID 438326.

- Widmaier E (2006). Vander's Human Physiology. McGraw Hill. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-07-282741-5.

- Mithieux G, Rajas F, Gautier-Stein A (October 2004). "A novel role for glucose 6-phosphatase in the small intestine in the control of glucose homeostasis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (43): 44231–44234. doi:10.1074/jbc.R400011200. PMID 15302872.

- Chen J, Lee HJ, Wu X, Huo L, Kim SJ, Xu L, et al. (February 2015). "Gain of glucose-independent growth upon metastasis of breast cancer cells to the brain". Cancer Research. 75 (3): 554–565. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2268. PMC 4315743. PMID 25511375.

- Yip J, Geng X, Shen J, Ding Y (2017). "Cerebral Gluconeogenesis and Diseases". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 7: 521. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00521. PMC 5209353. PMID 28101056.

- Gerich JE (February 2010). "Role of the kidney in normal glucose homeostasis and in the hyperglycaemia of diabetes mellitus: therapeutic implications". Diabetic Medicine. 27 (2): 136–142. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02894.x. PMC 4232006. PMID 20546255.

- Overton TR, Drackley JK, Ottemann-Abbamonte CJ, Beaulieu AD, Emmert LS, Clark JH (July 1999). "Substrate utilization for hepatic gluconeogenesis is altered by increased glucose demand in ruminants". Journal of Animal Science. 77 (7): 1940–51. doi:10.2527/1999.7771940x. PMID 10438042.

- Donkin SS, Armentano LE (February 1995). "Insulin and glucagon regulation of gluconeogenesis in preruminating and ruminating bovine". Journal of Animal Science. 73 (2): 546–51. doi:10.2527/1995.732546x. PMID 7601789.

- Voet D, Voet J, Pratt C (2008). Fundamentals of Biochemistry. John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-470-12930-2.

- Christos Chinopoulos (2020), From Glucose to Lactate and Transiting Intermediates Through Mitochondria, Bypassing Pyruvate Kinase: Considerations for Cells Exhibiting Dimeric PKM2 or Otherwise Inhibited Kinase Activity, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.543564/full

- Chakravarty K, Cassuto H, Reshef L, Hanson RW (2005). "Factors that control the tissue-specific transcription of the gene for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-C". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 40 (3): 129–54. doi:10.1080/10409230590935479. PMID 15917397. S2CID 633399.

- He L, Sabet A, Djedjos S, Miller R, Sun X, Hussain MA, et al. (May 2009). "Metformin and insulin suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis through phosphorylation of CREB binding protein". Cell. 137 (4): 635–46. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.016. PMC 2775562. PMID 19450513.

- Hatting M, Tavares CD, Sharabi K, Rines AK, Puigserver P (January 2018). "Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1411 (1): 21–35. Bibcode:2018NYASA1411...21H. doi:10.1111/nyas.13435. PMC 5927596. PMID 28868790.

- Wang Y, Tang H, Ji X, Zhang Y, Xu W, Yang X, et al. (January 2018). "Expression profile analysis of long non-coding RNAs involved in the metformin-inhibited gluconeogenesis of primary mouse hepatocytes". International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 41 (1): 302–310. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2017.3243. PMC 5746302. PMID 29115403.

- Mutel E, Gautier-Stein A, Abdul-Wahed A, Amigó-Correig M, Zitoun C, Stefanutti A, et al. (December 2011). "Control of blood glucose in the absence of hepatic glucose production during prolonged fasting in mice: induction of renal and intestinal gluconeogenesis by glucagon". Diabetes. 60 (12): 3121–31. doi:10.2337/db11-0571. PMC 3219939. PMID 22013018.

- Lee S, Dong HH (May 2017). "FoxO integration of insulin signaling with glucose and lipid metabolism". The Journal of Endocrinology. 233 (2): R67–R79. doi:10.1530/JOE-17-0002. PMC 5480241. PMID 28213398.

- Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, Chandramouli V, et al. (December 2000). "Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes". Diabetes. 49 (12): 2063–2069. doi:10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. PMC 2995498. PMID 11118008. Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, Chandramouli V, et al. (December 2000). "Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes". Diabetes. 49 (12): 2063–2069. doi:10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. PMC 2995498. PMID 11118008. (82 KiB)

- Harrison SA, Lane N (December 2018). "Life as a guide to prebiotic nucleotide synthesis". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5176. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07220-y. PMC 6289992. PMID 30538225.

- Say RF, Fuchs G (April 2010). "Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase/phosphatase may be an ancestral gluconeogenic enzyme". Nature. 464 (7291): 1077–1081. doi:10.1038/nature08884. PMID 20348906.

- Muchowska KB, Varma SJ, Moran J (August 2020). "Nonenzymatic Metabolic Reactions and Life's Origins". Chemical Reviews. 120 (15): 7708–7744. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00191. PMID 32687326.

- Messner CB, Driscoll PC, Piedrafita G, De Volder MF, Ralser M (July 2017). "Nonenzymatic gluconeogenesis-like formation of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate in ice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (28): 7403–7407. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702274114. PMC 5514728. PMID 28652321.

- Ralser, Markus (2018-08-30). "An appeal to magic? The discovery of a non-enzymatic metabolism and its role in the origins of life". The Biochemical Journal. 475 (16): 2577–2592. doi:10.1042/BCJ20160866. ISSN 1470-8728. PMC 6117946. PMID 30166494.

.svg.png.webp)