Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque (Arabic: الجامع الأموي, romanized: al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus, located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the largest and oldest mosques in the world. Its religious importance stems from the eschatological reports concerning the mosque, and historic events associated with it. Christian and Muslim tradition alike consider it the burial place of John the Baptist's head, a tradition originating in the 6th century. Muslim tradition holds that the mosque will be the place Jesus will return before the End of Days. Two shrines inside the premises commemorate the Islamic prophet Muhammad's grandson Husayn ibn Ali, whose martyrdom is frequently compared to that of John the Baptist and Jesus.

| Umayyad Mosque | |

|---|---|

الْجَامِع الْأُمَوِي | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Status | Intact |

| Location | |

| Location | Damascus, Damascus Governorate |

| Country | Syria |

Courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque in Old Damascus  Location within Syria | |

| Geographic coordinates | 33°30′41″N 36°18′24″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Islamic |

| Style | Umayyad |

| Completed | 715 CE |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 3 |

| Minaret height | 77 m (253 ft) |

| Materials | Stone, marble, tile, mosaic |

| Official name | Ancient City of Damascus |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 20 |

| Region | Arab States |

The site has been used as a house of worship since the Iron Age, when the Arameans built on it a temple dedicated to their god of rain, Hadad. Under Roman rule, beginning in 64 CE, it was converted into the center of the imperial cult of Jupiter, the Roman god of rain, becoming one of the largest temples in Syria. When the empire in Syria transitioned to Christian Byzantine rule, Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395) transformed it into a cathedral and the seat of the second-highest ranking bishop in the Patriarchate of Antioch.

After the Muslim conquest of Damascus in 634, part of the cathedral was designated as a small prayer house (musalla) for the Muslim conquerors. As the Muslim community grew, the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I (r. 705–715) confiscated the rest of the cathedral for Muslim use, returning to the Christians other properties in the city as compensation. The structure was largely demolished and a grand congregational mosque complex was built in its place. The new structure was built over nine years by thousands of laborers and artisans from across the Islamic and Byzantine empires at considerable expense and was funded by the war booty of Umayyad conquests and taxes on the Arab troops of Damascus. Unlike the simpler mosques of the time, the Umayyad Mosque had a large basilical plan with three parallel aisles and a perpendicular central nave leading from the mosque's entrance to the world's second concave mihrab (prayer niche). The mosque was noted for its rich compositions of marble paneling and its extensive gold mosaics of vegetal motifs, covering some 4,000 square metres (43,000 sq ft), likely the largest in the world.

Under Abbasid rule (750–860), new structures were added, including the Dome of the Treasury and the Minaret of the Bride, while the Mamluks (1260–1516) undertook major restoration efforts and added the Minaret of Qaytbay. The Umayyad Mosque innovated and influenced nascent Islamic architecture, with other major mosque complexes, including the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Spain and the al-Azhar Mosque of Egypt, based on its model. Although the original structure has been altered several times due to fire, war damage, and repairs, it is one of the few mosques to maintain the same form and architectural features of its 8th-century construction, as well as its Umayyad character.

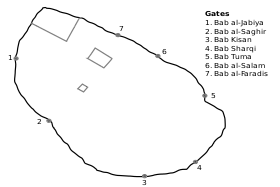

| Old City of Damascus |

|---|

| Location of the Mosque in Relation to the Citadel and the Azem Palace |

History

Pre-Islamic period

The site of the Umayyad Mosque is attested for as a place of worship since the Iron Age. Damascus was the capital of the Aramaean state Aram-Damascus and a large temple was dedicated to Hadad-Ramman, the god of thunderstorms and rain, and was erected at the site of the present-day mosque. One stone remains from the Aramaean temple, dated to the rule of King Hazael, and is currently on display in the National Museum of Damascus.[1]

The Temple of Hadad-Ramman continued to serve a central role in the city, and when the Roman Empire conquered Damascus in 64 BCE, they assimilated Hadad with their own god of thunder, Jupiter.[2] Thus, they engaged in a project to reconfigure and expand the temple under the direction of Damascus-born architect Apollodorus, who created and executed the new design.[3]

The new Temple of Jupiter became the center of the imperial cult of Jupiter and was served as a response to the Second Temple in Jerusalem.[4] The Temple of Jupiter would attain further additions during the early Roman period, mostly initiated by high priests who collected contributions from the wealthy citizens of Damascus.[5] The eastern gateway of the courtyard was expanded during the reign of Septimius Severus (r. 193–211).[6] By the 4th century, the temple was especially renowned for its size and beauty. It was separated from the city by two sets of walls. The first, wider wall spanned a wide area that included a market, and the second wall surrounded the actual sanctuary of Jupiter. It was the largest temple in Roman Syria.[7]

In 391, the Temple of Jupiter was converted into a cathedral by the Christian emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395).[8] It served as the seat of the Bishop of Damascus, who ranked second within the Patriarchate of Antioch after the patriarch himself.[9]

Foundation and construction

Damascus was captured by Muslim Arab forces led by Khalid ibn al-Walid in 634. In 661, the Islamic Caliphate came under the rule of the Umayyad dynasty, which chose Damascus to be the administrative capital of the Muslim world.[11] The Byzantine cathedral had remained in use by the local Christians, but a prayer room (musalla) for Muslims was constructed on the southeastern part of the building.[12][13] The musalla did not have the capacity to house the rapidly growing number of Muslim worshippers in Damascus. The city otherwise lacked sufficient free space for a large congregational mosque.[14] The sixth Umayyad caliph, al-Walid I (r. 705–715), resolved to construct such a mosque on the site of the cathedral in 706.[11]

Al-Walid personally supervised the project and had most of the cathedral, including the musalla, demolished. The construction of the mosque completely altered the layout of the building, though it preserved the outer walls of the temenos (sanctuary or inner enclosure) of the Roman-era temple.[12][13] While the church (and the temples before it) had the main building located at the centre of the rectangular enclosure, the mosque's prayer hall is placed against its south wall. The architect recycled the columns and arcades of the church, dismantling and repositioning them in the new structure. Professor Alain George has re-examined the architecture and design of this first mosque on the site via three previously untranslated poems and the descriptions of medieval scholars.[15] Besides its use as a large congregational mosque for the Damascenes, the new house of worship was meant as a tribute to the city.[16][17][18]

In response to Christian protest at the move, al-Walid ordered all the other confiscated churches in the city to be returned to the Christians as compensation. The mosque was completed in 711,[19][20] or in 715, shortly after al-Walid's death, by his successor, Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 715–717).[16][17][18] According to 10th-century Persian historian Ibn al-Faqih, somewhere between 600,000 and 1,000,000 gold dinars were spent on the project.[16][21] The historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship notes that the field army of Damascus, numbering some 45,000 soldiers, were taxed a quarter of their salaries for nine years to pay for its construction.[19][20] Coptic craftsmen as well as Persian, Indian, Greek, and Moroccan laborers provided the bulk of the labor force which consisted of 12,000 people.[16][21]

Layout design

The plan of the new mosque was innovative and highly influential in the history of early Islamic architecture.[22][23] The earliest mosques before this had been relatively plain hypostyle structures (a flat-roof hall supported by columns), but the new mosque in Damascus introduced a more basilical plan with three parallel aisles and a perpendicular central nave. The central nave, which leads from the main entrance to the mihrab (niche in the qibla wall) and features a central dome, provided a new aesthetic focus which may have been designed to emphasize the area originally reserved for the caliph during prayers, near the mihrab.[22][23] There is some uncertainty as to whether the dome was originally directly in front of the mihrab (as in many later mosques) or in its current position mid-way along the central nave.[24] Scholars have attributed the design of the mosque's plan to the influences of Byzantine Christian basilicas in the region.[22][25] Rafi Grafman and Myriam Rosen-Ayalon have argued that the first Umayyad Al-Aqsa Mosque built in Jerusalem, begun by Abd al-Malik (al-Walid's father) and now replaced by later constructions, had a layout very similar to the current Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and that it probably served as a model for the latter.[26]

The mosque initially had no minaret towers, as this feature of mosque architecture was not established until later. However, at least two of the corners of the mosque's outer wall had short towers, platforms, or roof shelters which were used by the muezzin to issue the call to prayer (adhān), constituting a type of proto-minaret. These features were referred to as a mi'd͟hana ("place of the adhān") or as a ṣawma῾a ("monk's cell", due to their small size) in historical Arabic sources.[27][28] Arabic sources indicated that they were former Roman towers which already stood at the corners of the temenos before the mosque's construction and were simply left intact and reused after construction.[27][29]

Decoration

The mosque was richly decorated. A rich composition of marble paneling covered the lower walls, though only minor examples of the original marbles have survived today near the east gate.[31] The walls of the prayer hall were raised above the level of the old temenos walls, which allowed for new windows to be inserted in the upper walls. The windows had ornately carved grilles that foreshadowed the styles of windows in later Islamic architecture.[31][32]

The most celebrated decorative element of all was the revetment of mosaics, which originally covered much of the courtyard and the interior hall. The best-preserved remains are still visible in the courtyard today.[lower-alpha 1]

By some estimates, the original mosque had the largest area of gold mosaics in the world, covering approximately 4,000 square metres (43,000 sq ft).[23] The mosaics depict landscapes and buildings in a characteristic late Roman style.[35][36] They reflected a wide variety of artistic styles used by mosaicists and painters since the 1st century CE, but the combined use of all these different styles in the same place was innovative at the time.[37] Similar to the Dome of the Rock, built earlier by Abd al-Malik, vegetation and plants were the most common motif, but those of the Damascus mosque are more naturalistic.[37] In addition to the large landscape depictions, a mosaic frieze with an intricate vine motif (referred to as the karma in Arabic historical sources) once ran around the walls of the prayer hall, above the level of the mihrab.[38] The only notable omission is the absence of human and animal figures, which was likely a new restriction imposed by the Muslim patron.[37]

.jpg.webp)

Historical Arabic sources, often written in later centuries, suggest that both the craftsmen and the materials employed to create the mosque's mosaics were imported from the Byzantine capital of Constantinople.[40][41][42] The 12th-century historian Ibn Asakir claimed that al-Walid pressured the Byzantine emperor into sending him 200 craftsmen by threatening to destroy all churches inside Umayyad territory if he refused.[43][44] Many scholars, based on such evidence from Arabic sources, have accepted a Byzantine (Constantinopolitan) origin for the mosaics,[45][46] while some, such as Creswell, have interpreted the story as a later embellishment of Muslim historians with a symbolic political significance.[47]

Art historian Finbarr Barry Flood notes that historical sources report many other apparent gifts of artisans and materials from the Byzantine emperors to the Umayyad caliphs and other rulers, probably reflecting a widespread admiration for Byzantine craftsmanship that continued in the early Islamic period.[48] He notes that while Byzantine influence is indeed apparent in the mosque's mosaic imagery, there are multiple ways in which Byzantine mosaicists could have contributed to its production, including a collaboration with local craftsmen.[49] Some scholars argue that the mosaic techniques in both the Dome of the Rock and the Umayyad Mosque, including their distinctive colour scheme, are more clearly consistent with the craftsmanship of Syro-Palestinian or Egyptian mosaicists. Archeologist Judith McKenzie suggests that the mosaics could have been designed by local artisans who oversaw their production, while any mosaicists sent from Constantinople could have been working under their supervision.[50] A recent 2022 study of the chemical composition of mosaic tesserae in the Umayyad Mosque concluded that the majority were produced in Egypt around the time of the mosque's construction, matching other recent studies of samples from the Dome of the Rock and Khirbat al-Majfar that came to the same conclusion.[42]

Scholars have long debated the meaning of the mosaic imagery. Some historical Muslim writers and some modern scholars have interpreted them as a topographical representation of all the cities in the known world (or within the Umayyad world), some have interpreted them as a representation of Damascus itself and the Barada River, and other scholars interpret them as a depiction of Paradise.[37][51] The earliest known interpretation of the mosaics is by the 10th-century geographer al-Muqaddasi, who suggested a topographical meaning, commenting that "there is hardly a tree or a notable town that has not been pictured on these walls."[37] An early example of the Paradise interpretation dates from the writings of Ibn al-Najjar in the 12th century.[52] This interpretation has been favoured by more recent scholarship.[37] Some of the Qur'anic inscriptions that were originally present on the qibla wall of the mosque, mentioning the Day of Judgment and promising the reward of a heavenly garden (al-janna), may support this interpretation.[53] Another clue is an account by historian Ibn Zabala in 814, which reports that one of the mosaicists who worked for al-Walid's reconstruction of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina (contemporary with the construction in Damascus) directly explained the mosaics there as a reproduction of the trees and palaces of Paradise,[54] which suggests that the contemporary Umayyad mosaics in Damascus had the same intention.[55]

In this interpretation, the lack of human figures in these scenes possibly represents a Paradise that stands empty until the arrival of its human inhabitants at the end of time.[53] Other motifs in the mosaics have been cited to support a paradisal meaning and the imagery has been compared with both the descriptions of Paradise in the Qur'an and the earlier iconography of paradisal imagery in Late Antique art.[56] According to Judith McKenzie, there is a similarity between certain architectural elements depicted in the Umayyad mosaics and those shown in Pompeian frescoes (such as broken pediments and tholoi with tented roofs and Corinthian columns), as well as some early Christian and Byzantine art, which are most likely depictions of the architecture of Hellenistic Alexandria.[57] In Roman and Late Antique art, Alexandrian and Egyptian landscapes had a paradisal connotation.[58] McKenzie argues that the Umayyad mosaics, extending these traditions, can thus be understood as a depiction of Paradise.[59] The possibility also remains that the mosaic scenes combine more than one of these meanings at the same time; for example, by using paradisal imagery to represent Damascus or the Umayyad realm as an idealized, earthly paradise.[37][51]

The mihrab

The original mihrab was one of the first concave mihrabs in the Islamic world, the second one known to exist after the one created in 706–707 during al-Walid's reconstruction of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina.[60][22] The exact appearance of the mosque's original main mihrab is uncertain, due to the multiple repairs and restorations that took place over the centuries. Ibn Jubayr, who visited the mosque in 1184, described the inside of the mihrab as filled with miniature blind arcades whose arches resembled "small mihrabs", each filled with inlaid mother-of-pearl mosaics and framed by spiral columns of marble.[61] This mihrab was famed across the Islamic world for its beauty, as noted by other writers of the era.[61]

Its appearance may have been imitated by other surviving mihrabs built under the Mamluk sultans al-Mansur Qalawun and al-Nasir Muhammad in the 13th and 14th centuries, such as the richly-decorated mihrab of Qalawun's mausoleum in Cairo (completed in 1285).[62] Scholars generally assume that the mihrab described by Ibn Jubayr dated from a restoration of the mosque in 1082.[61] Another restoration occurred after 1401 and this version, which survived until another fire in 1893, was again decorated with miniature arcades, while its semi-dome was filled with coffering similar to Roman architecture.[61][63] Finbarr Barry Flood has suggested that the perpetuation of the mihrab's arcaded decoration across several restorations indicates that the medieval restorations were aimed at preserving at least some of the original mihrab's appearance, and therefore the 8th-century Umayyad mihrab may have had these features.[61]

Abbasid and Fatimid era

Following the toppling of the Umayyads in 750, the Abbasid dynasty came to power and moved the capital of the Caliphate to Baghdad. Apart from the attention given for strategic and commercial purposes, the Abbasids had no interest in Damascus. Thus, the Umayyad Mosque reportedly suffered under their rule, with little recorded building activity between the 8th and 10th centuries.[64] However, the Abbasids did consider the mosque to be a major symbol of Islam's triumph, and thus it was spared the systematic eradication of the Umayyad legacy in the city.[65] In 789–90 the Abbasid governor of Damascus, al-Fadl ibn Salih ibn Ali, constructed the Dome of the Treasury with the purpose of housing the mosque's funds.[65] The so-called Dome of the Clock, standing in the eastern part of the courtyard, may have also been erected originally by the same Abbasid governor in 780.[66][67] The 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi credited the Abbasids for building the northern minaret (Madhanat al-Arous, meaning 'Minaret of the Bride') of the mosque in 831 during the reign of Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833).[64][65] This was accompanied by al-Ma'mun's removal and replacement of Umayyad inscriptions in the mosque.[68]

By the early 10th century, a monumental water clock had been installed by the entrance in the western part of the southern wall of the mosque, which was consequently known as Bab al-Sa'a ('Gate of the Clock') at the time but is known today as Bab al-Ziyada.[69] This clock seems to have stopped functioning by the middle of the 12th century.[70] Abbasid rule over Syria began crumbling during the early 10th century, and in the decades that followed, it came under the control of autonomous realms who were only nominally under Abbasid authority. The Fatimids of Egypt, who adhered to Shia Islam, conquered Damascus in 970, but few recorded improvements of the mosque were undertaken by the new rulers. The Umayyad Mosque's prestige allowed the residents of Damascus to establish the city as a center for Sunni intellectualism, enabling them to maintain relative independence from Fatimid religious authority.[71] In 1069, large sections of the mosque, particularly the northern wall, were destroyed in a fire as a result of an uprising by the city's residents against the Fatimids' Berber army who were garrisoned there.[72]

Seljuk and Ayyubid era

The Sunni Muslim Seljuk Turks gained control of the city in 1078 and restored the nominal rule of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Seljuk ruler Tutush (r. 1079–1095) initiated the repair of damage caused by the 1069 fire.[73] In 1082, his vizier, Abu Nasr Ahmad ibn Fadl, had the central dome restored in a more spectacular form;[74] the two piers supporting it were reinforced and the original Umayyad mosaics of the northern inner façade were renewed. The northern riwaq ('portico') was rebuilt in 1089.[75] The Seljuk atabeg of Damascus, Toghtekin (r. 1104–1128), repaired the northern wall in 1110 and two inscribed panels located above its doorways were dedicated to him.[76] In 1113, the Seljuk atabeg of Mosul, Sharaf al-Din Mawdud (r. 1109–1113), was assassinated in the Umayyad Mosque.[77] As the conflict between Damascus and the Crusaders intensified in the mid-12th century, the mosque was used as a principal rallying point calling on Muslims to defend the city and return Jerusalem to Muslim hands. Prominent imams, including Ibn Asakir, preached a spiritual jihad ('struggle') and when the Crusaders advanced towards Damascus in 1148, the city's residents heeded their calls; the Crusader army withdrew as a result of their resistance.[78]

In Damascus there is a mosque that has no equal in the world, not one with such fine proportion, nor one so solidly constructed, nor one vaulted so securely, nor one more marvelously laid out, nor one so admirably decorated in gold mosaics and diverse designs, with enameled tiles and polished marbles.

—Muhammad al-Idrisi, 1154[79]

During the reign of the Zengid ruler Nur ad-Din Zangi, which began in 1154, a second monumental clock, the Jayrun Water Clock, was built on his personal orders.[80] It was constructed outside the eastern entrance to the mosque, called Bab Jayrun, by the architect Muhammad al-Sa'ati, was rebuilt by al-Sa'ati following a fire in 1167, and was eventually repaired by his son, Ridwan, in the early 13th century. It may have survived into the 14th century.[81] The Arab geographer al-Idrisi visited the mosque in 1154.[65]

Damascus witnessed the establishment of several religious institutions under the Ayyubids, but the Umayyad Mosque retained its place as the center of religious life in the city. Muslim traveler Ibn Jubayr described the mosque as containing many different zawaya (religious lodges) for religious and Quranic studies. In 1173, the northern wall of the mosque was damaged again by the fire and was rebuilt by the Ayyubid sultan, Saladin (r. 1174–1193), along with the Minaret of the Bride,[82] which had been destroyed in the 1069 fire.[65] During the internal feuds between later Ayyubid princes, the city was dealt a great deal of damage, and the mosque's eastern minaret—known as the 'Minaret of Jesus'—was destroyed at the hands of as-Salih Ayyub of Egypt while besieging as-Salih Ismail of Damascus in 1245.[83] The minaret was later rebuilt with little decoration.[84] Saladin, along with many of his successors, were buried around the Umayyad Mosque (see Mausoleum of Saladin).[85]

Mamluk era

The Mongols, under the leadership of the Nestorian Christian Kitbuqa, with the help of some submitted Western Christian forces, captured Damascus from the Ayyubids in 1260 while Kitbuqa's superior Hulagu Khan had returned to the Mongol Empire for other business. Bohemond VI of Antioch, one of the Western Christian generals in the invasion, ordered Catholic Mass to be performed in the Umayyad Mosque.[86] However, the Muslim Mamluks of Egypt, led by Sultan Qutuz and Baybars, wrested control of the city from the Mongols later in the same year, killing Kitbuqa in the Battle of Ain Jalut, and the purpose of the Mosque was returned from Christian to its original Islamic function. In 1270, Baybars, by now sultan, ordered extensive restorations to the mosque, particularly its marble, mosaics and gildings. According to Baybars' biographer, Ibn Shaddad, the restorations cost the sultan 20,000 dinars. Among the largest mosaic fragments restored was a 34.5 by 7.3 metres (113 by 24 ft) segment in the western portico called the "Barada panel".[87] The mosaics that decorated the mosque were a specific target of the restoration project and they had a major influence on Mamluk architecture in Syria and Egypt.[88]

In 1285, the Hanbali scholar Ibn Taymiyya started teaching Qur'an exegesis in the mosque. When the Ilkhanid Mongols under Ghazan invaded the city in 1300, Ibn Taymiyya preached jihad, urging the citizens of Damascus to resist their occupation. The Mamluks under Sultan Qalawun drove out the Mongols later that year.[89] When Qalawun's forces entered the city, the Mongols attempted to station several catapults in the Umayyad Mosque because the Mamluks had started fires around the citadel to prevent Mongol access to it. The attempt failed as the Mamluks burned the catapults before they were placed in the mosque.[90]

The Mamluk viceroy of Syria, Tankiz, carried out restoration work in the mosque in 1326–1328. He reassembled the mosaics on the qibla wall and replaced all the marble tiles in the prayer hall. Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad also undertook major restoration work for the mosque in 1328. He demolished and completely rebuilt the unstable qibla wall and moved the Bab al-Ziyadah gate to the east.[87] Much of that work was damaged during a fire that burned the mosque in 1339.[88] Islamic art expert, Finbarr Barry Flood, describes the Bahri Mamluks' attitude towards the mosque as an "obsessive interest" and their efforts at maintaining, repairing, and restoring the mosque were unparalleled in any other period of Muslim rule.[91] The Arab astronomer Ibn al-Shatir worked as the chief muwaqqit ('religious timekeeper') and the chief muezzin at the Umayyad Mosque from 1332 until he died in 1376.[92] He erected a large sundial on the mosque's northern minaret in 1371, now lost. A replica was installed in its place in the modern period.[93][94] The Minaret of Jesus was burnt down in a fire in 1392.[95]

The Mongol conqueror Timur besieged Damascus in 1400. He ordered the burning of the city on 17 March 1401, and the fire ravaged the Umayyad Mosque. The eastern minaret was reduced to rubble, and the central dome collapsed.[96] A southwestern minaret was added to the mosque in 1488 during the reign of Mamluk sultan Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496).[97]

Ottoman era

Damascus was conquered from the Mamluks by the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim I in 1516. The first Friday prayer performed in Selim's name in the Umayyad Mosque was attended by the sultan himself.[98][99] The Ottomans used an endowment system (waqf) for religious sites as a means to link the local population with the central authority. The waqf of the Umayyad Mosque was the largest in the city, employing 596 people. Supervisory and clerical positions were reserved for Ottoman officials while religious offices were held mostly by members of the local ulema (Muslim scholars).[100] Although the awqaf (plural of "waqf") were taxed, the waqf of the Umayyad Mosque was exempted from taxation.[101] In 1518, the Ottoman governor of Damascus and supervisor of the mosque's waqf, Janbirdi al-Ghazali, had the mosque repaired and redecorated as part of his architectural reconstruction program for the city.[102]

The prominent Sufi scholar Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi taught regularly at the Umayyad Mosque starting in 1661.[103]

The khatib (preacher) of the Umayyad Mosque was one of the three most influential religious officials in Ottoman Damascus, the other two being the Hanafi mufti and the naqib al-ashraf. He served as a link between the imperial government in Constantinople and the elites of Damascus and was a key shaper of public opinion in the city. By 1650 members of the mercantile and scholarly Mahasini family held the position, retaining it for much of the 18th and early and mid-19th centuries, partly due to their links with the Shaykh al-Islam in the imperial capital. In the late 19th century, another Damascene family with connections in Constantinople, the Khatibs, vied for the position. After the death of the Mahasini preacher in 1869, a member of the Khatibs succeeded him.[104]

The mosque's prayer hall was once again ravaged and partly destroyed by fire in 1893.[105][106] A laborer engaging in repair work accidentally started the fire when he was smoking his nargila (water pipe).[106] The fire destroyed the inner fabric of the prayer hall and caused the collapse of the mosque's central dome. The Ottomans fully restored the mosque, largely maintaining the original layout.[107] The restoration process, which lasted nine years, did not attempt to reproduce the original decoration.[106] The central mihrab was replaced and the dome was rebuilt in a contemporary Ottoman style. The rubble and damaged elements from the fire, including some of the original pillars and mosaic remains, were simply disposed of.[106][38][23]

_(14597903298).jpg.webp)

Until 1899 the mosque's library included the "very old" Qubbat al-Khazna collection;[108] "most of its holdings were given to the German emperor Wilhelm II and only a few pieces kept for the National Archives in Damascus."[109]

It is the burial place of the first three officers of the Ottoman Aviation Squadrons who died on mission, in this case the Istanbul-Cairo expedition in 1914. They were Navy Lieutenant Fethi Bey and his navigator, Artillery First Lieutenant Sadık Bey and Artillery Second Lieutenant Nuri Bey.

Modern era

The Umayyad Mosque underwent major restorations in 1929 during the French Mandate over Syria and in 1954 and 1963 under the Syrian Republic.[110]

In the 1980s and in the early 1990s, Syrian president Hafez al-Assad ordered a wide-scale renovation of the mosque.[111] The methods and concepts of Assad's restoration project were heavily criticized by UNESCO, but the general approach in Syria was that the mosque was more of a symbolic monument rather than a historical one and thus, its renovation could only enhance the mosque's symbolism.[112]

In 1990s, Mohammed Burhanuddin constructed a zarih of the martyrs of the Battle of Karbala,[113] whose heads were brought to the Mosque after their defeat at the hands of the then Umayyad caliph, Yazid I.

In 2001, Pope John Paul II visited the mosque, primarily to visit the relics of John the Baptist. It was the first time a pope paid a visit to a mosque.[114]

On March 15, 2011, the first significant protests related to the Syrian civil war began at the Umayyad Mosque when 40–50 worshipers gathered outside the complex and chanted pro-democracy slogans. Syrian security forces swiftly quelled the protests and have since cordoned off the area during Friday prayers to prevent large-scale demonstrations.[115][116]

Architecture

The ground plan of the Umayyad Mosque is rectangular in shape and measures 97 meters (318 ft) by 156 meters (512 ft).[117] A large courtyard occupies the northern part of the mosque complex, while the prayer hall or haram ('sanctuary') covers the southern part. The mosque is enclosed by four exterior walls which were part of the temenos of the original Roman temple.[118]

Sanctuary

Three arcades make up the interior space of the sanctuary. They are parallel to the direction of prayer which is towards Mecca. The arcades are supported by two rows of stone Corinthian columns. Each of the arcades contain two levels. The first level consists of large semi-circular arches, while the second level is made up of double arches. This pattern is the same repeated by the arcades of the courtyard. The three interior arcades intersect in the center of the sanctuary with a larger, higher arcade that is perpendicular to the qibla wall and faces the mihrab and the minbar.[117] The central transept divides the arcades into two halves each with eleven arches. The entire sanctuary measures 136 meters (446 ft) by 37 meters (121 ft) and takes up the southern half of the mosque complex.[119]

Four mihrabs line the sanctuary's rear wall, the main one being the Great Mihrab which is located roughly at the center of the wall. The Mihrab of the Sahaba, named after the sahaba ('companions of Muhammad') is situated in the eastern half. According to the 9th-century Muslim engineer Musa ibn Shakir, the latter mihrab was built during the mosque's initial construction and it became the third niche-formed mihrab in Islam's history.[119]

The central dome of the mosque is known as the 'Dome of the Eagle' (Qubbat an-Nisr) and located atop the center of the prayer hall.[120] The original wooden dome was replaced by one built of stone following the 1893 fire. It receives its name because it is thought to resemble an eagle, with the dome itself being the eagle's head while the eastern and western flanks of the prayer hall represent the wings.[121] With a height of 36 meters (118 ft), the dome rests on an octagonal substructure with two arched windows on each of its sides. It is supported by the central interior arcade and has openings along its parameter.[117]

Courtyard

In the courtyard (sahn), the level of the stone pavement had become uneven over time due to several repairs throughout the mosque's history. Recent work on the courtyard has restored it to its consistent Umayyad-era levels.[117] Arcades (riwaq) surround the courtyard supported by alternating stone columns and piers. There is one pier in between every two columns. Because the northern part of the courtyard had been destroyed in an earthquake in 1759, the arcade is not consistent; when the northern wall was rebuilt the columns that were supporting it were not.[117] The courtyard and its arcades contain the largest preserved remnants of the mosque's Umayyad-era mosaic decoration.[33]

Several domed pavilions stand in the courtyard. The Dome of the Treasury is an octagonal structure decorated with mosaics, standing on eight Roman columns in the western part of the courtyard. Its 8th-century mosaics were largely remade in the late 20th-century restoration.[122][123] In a mirror position on the other side of the courtyard is the Dome of the Clock, another octagonal domed pavilion.[66] Near the middle of the courtyard, sheltering an ablutions fountain at ground level, is a rectangular pavilion which is a modern reconstruction of a late Ottoman pavilion.[124]

Minarets

Within the Umayyad Mosque complex are three minarets. The Minaret of Isa on the southeast corner, the Minaret of Qaytbay (also called Madhanat al-Gharbiyya) on the southwest corner, and the Minaret of the Bride located along the northern wall.

Minaret of the Bride

The Minaret of the Bride was the first one built and is located on the mosque's northern wall. The exact year of the minaret's original construction is unknown.[65] The bottom part of the minaret most likely dates back to the Abbasid era in the 9th century.[65][127] While it is possible that the Umayyads built it, there is no indication that a minaret on the northern wall was a part of al-Walid I's initial concept. Al-Muqaddasi visited the minaret in 985 when Damascus was under Abbasid control and described it as "recently built". The upper segment was constructed in 1174.[65] This minaret is used by the muezzin for the call to prayer (adhan) and there is a spiral staircase of 160 stone steps that lead to the muezzin's calling position.[128] The Minaret of the Bride is divided into two sections; the main tower and the spire which are separated by a lead roof. The oldest part of the minaret, or the main tower, is square in shape, has four galleries,[128] and consists of two different forms of masonry; the base consists of large blocks, while the upper section is built of dressed stone. There are two light openings near the top of the main tower, before the roof, with horseshoe arches and cubical capitals enclosed in a single arch. A smaller arched corbel is located below these openings.[129] According to local legend, the minaret is named after the daughter of the merchant who provided the lead for the minaret's roof who was married to Syria's ruler at the time. Attached to the Minaret of the Bride is the 18th-century replica of the 14th-century sundial built by Ibn al-Shatir.[127]

Minaret of Isa

The Minaret of Isa is around 77 meters (253 ft) in height and the tallest of the three minarets.[130][131] Some sources claim it was originally built by the Abbasids in the 9th century.[127] The main body of the current minaret was built by the Ayyubids in 1247, but the upper section was constructed by the Ottomans.[131] The main body of the minaret is square-shaped and the spire is octagonal. It tapers to a point and is surmounted by a crescent (as are the other two minarets.) Two covered galleries are situated in the main body and two open galleries are located on the spire.[128] Islamic belief holds that Isa (Jesus) will descend from heaven during the time of the Fajr prayer and will pray behind the Mahdi. He will then confront the Antichrist. According to local Damascene tradition, relating from hadith,[126] Isa will reach earth via the Minaret of Isa, hence its name.[131] Ibn Kathir, a prominent 14th-century Muslim scholar, backed this notion.[132]

Minaret of Qaytbay

The Minaret of Qaytbay, or the Western Minaret, was built by Qaytbay in 1488.[127] He also commissioned its renovation due to the 1479 fire. The minaret displays strong Islamic-era Egyptian architectural influence typical of the Mamluk period.[131] It is octagonal in shape and built in receding sections with three galleries.[128] It is generally believed that both the Minaret of Jesus and the Western Minaret were built on the foundation of ancient Roman towers. [131]

Influence on mosque architecture

The Umayyad Mosque is one of the few early mosques in the world to have maintained the same general structure and architectural features since its initial construction in the early 8th century. Its Umayyad character has not been significantly altered. Since its establishment, the mosque has served as a model for congregational mosque architecture in Syria as well as globally. According to Flood, "the construction of the Damascus mosque not only irrevocably altered the urban landscape of the city, inscribing upon it a permanent affirmation of Muslim hegemony, but by giving the Syrian congregational mosque its definitive form it also transformed the subsequent history of the mosque in general."[133] Examples of the Umayyad Mosque's ground plan being used as a prototype for other mosques in the region include the al-Azhar Mosque and Baybars Mosque in Cairo, the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Spain, and the Bursa Grand Mosque and the Selimiye Mosque in Turkey.[134]

Religious significance

The mosque is the fourth holiest site of Islam.[135][136][137] A Christian tradition dating to the 6th century developed an association between the former cathedral structure and John the Baptist. Legend had it that his head was buried there.[8] Ibn al-Faqih relays that during the construction of the mosque, workers found a cave-chapel which had a box containing the head of John the Baptist, known as Yahya ibn Zakariya by Muslims. Upon learning of that and examining it, al-Walid I ordered the head buried under a specific pillar in the mosque that was later inlaid with marble.[138]

Muslim tradition holds that the mosque will be the place Jesus will return before the End of Days.

It holds great significance to Shia and Sunni Muslims, as this was the destination of the ladies and children of the family of Muhammad, made to walk here from Iraq, following the Battle of Karbala.[139] Furthermore, it was the place where they were imprisoned for 60 days.[140] Two shrines commemorating the Islamic prophet Muhammad's grandson Husayn ibn Ali, whose martyrdom is frequently compared to that of John the Baptist,[141] and Jesus,[142] exist within the building premises.[143]

The following are structures found within the Mosque that bear great importance:

West Side:

- The entrance gate (known as "Bāb as-Sā'at") — The door marks the location where the prisoners of Karbalā were made to stand for 72 hours before being brought inside.[144] During this time, Yazīd I had the town and his palace decorated for their arrival.,[144]

South Wing (main hall):

- Shrine of John the Baptist (Arabic: Yahyā) — According to Al-Suyuti, Ibrahim stated that since the creation of the world[145] the Heavens and the Earth wept only for two people: Yahya and Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad[146]

- A white pulpit — Marks the place where Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin addressed the court of Yazīd after being brought from Karbalā[147]

- Raised floor (in front of the pulpit) — Marks the location where all the ladies and children (the household of Muhammad) were made to stand in the presence of Yazīd

- Wooden balcony (directly opposite the raised floor) – Marks the location where Yazīd sat in the court.

East Wing:

- A prayer rug and Mihrāb encased in a glass cubicle — Marks the place where Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin used to pray while imprisoned in the castle after the Battle of Karbala

- A metallic, cuboidal indentation in the wall — Marks the place where the head of Husayn ibn Ali was kept for display by Yazīd

- A Zarih — Marks the place where all the other heads of those who fell in Karbalā were kept within the Mosque.

See also

Notes

- The best-preserved sections of the mosaics today are located on the inner and outer facades of the western portico (arches) of the courtyard, as well as in the vestibule of the western entrance. Restitutions carried out to other sections after 1963 have been heavily criticized for their inauthenticity. Areas of original mosaic work generally appear darker today than areas of new (restored) mosaics. A large stretch of mosaics along the inner wall of the western portico, sometimes known as the "Barada panel", contains original Umayyad fragments, late 13th-century fragments from the time of the Mamluk sultan Baybars, and post-1963 restorations. The outer façade of the prayer hall's main entrance contains only limited fragments of original mosaic (in darker shades), with the rest restored after 1963. Some damaged remains of mosaics on the interior façade of this entrance, inside the prayer hall, date from a late 11th-century Seljuk-era restoration.[33][34]

References

- Burns 2007, p. 16.

- Burns 2007, p. 40.

- Calcani & Abdulkarim 2003, p. 28.

- Burns 2007, p. 65.

- Burns 2007, p. 62.

- Burns 2007, p. 72.

- Bowersock & Brown 2001, pp. 47–48.

- Burns 2007, p. 88.

- Darke 2010, p. 72.

- Burns 2009, pp. 104–105.

- Grafman & Rosen-Ayalon 1999, p. 7.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 22.

- Burns 2007, p. 112-114.

- Elisséeff 1965, p. 800.

- George 2021.

- Flood 2001, p. 2.

- Rudolff 2006, p. 177.

- Takeo Kamiya (2004). "Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria". Eurasia News. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 82.

- Elisséeff 1965, p. 801.

- Wolff 2007, p. 57.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 24.

- Enderlein 2011, p. 71.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 23.

- Grafman & Rosen-Ayalon 1999, pp. 10–11.

- Grafman & Rosen-Ayalon 1999, pp. 8–9.

- Hillenbrand, Robert; Burton-Page, J.; Freeman-Greenville, G.S.P. (1960–2007). "Manār, Manāra". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Minaret". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Damascus". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Burns 2009, pp. 103.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 25.

- Burns 2007, p. 115.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 25-26.

- Burns 2009, pp. 102–103.

- Rosenwein 2014, p. 56.

- Kleiner 2013, p. 264.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 26.

- Flood 1997.

- Burns 2009, p. 102.

- McKenzie 2007, pp. 366–367.

- Flood 2001, pp. 17–25.

- Schibille, Nadine; Lehuédé, Patrice; Biron, Isabelle; Brunswic, Léa; Blondeau, Étienne; Gratuze, Bernard (November 2022). "Origins and manufacture of the glass mosaic tesserae from the great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus". Journal of Archaeological Science. 147: 105675. Bibcode:2022JArSc.147j5675S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105675. ISSN 0305-4403. S2CID 252527878.

- McKenzie 2007, p. 367.

- Flood 2001, pp. 21–23.

- McKenzie 2007, p. 366.

- Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, pp. 25–26.

- Flood 2001, pp. 21–22.

- Flood 2001, pp. 22–24.

- Flood 2001, p. 24.

- McKenzie 2007, pp. 365–367.

- Flood 2001, p. 33.

- Georgopoulou, Maria (2017). "Geography, cartography and the architecture of power in the mosaics of the Great Mosque of Damascus". In Anderson, Christy; Koehler, Karen (eds.). The Built Surface: Architecture and the Visual Arts from Antiquity to the Enlightenment. Vol. 1. Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-351-74584-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-19. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- Flood 2001, p. 31.

- Birsch, Klaus (1988). "Observations on the Iconography of the Mosaics in the Great Mosque at Damascus". In Soucek, Priscilla Parsons (ed.). Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World: Papers from a Colloquium in Memory of Richard Ettinghausen, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 2-4 April 1980. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 18.

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2011). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8122-0728-6. Archived from the original on 2023-07-19. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- Flood 2001, pp. 25–33.

- McKenzie 2007, pp. 80, 362–367.

- McKenzie 2007, pp. 112, 364–365.

- McKenzie 2007, pp. 362–367.

- Fehérvári 1993, pp. 8–9.

- Flood 1997, p. 64.

- Flood 1997, p. 64-66.

- Flood 2001, p. 52.

- Flood 2001, pp. 124–126.

- Burns 2007, pp. 131–132.

- Burns 2007, pp. 132, 286 (note 10).

- Rudolff 2006, p. 162.

- Flood 2001, pp. 124–126, Some information used in the article is provided by the footnotes of this source: File:Dome of the Clocks, Umayyad Mosque.jpg.

- Flood 2001, pp. 118–121.

- Flood 2001, p. 118-121.

- Burns 2007, p. 139.

- Burns 2007, p. 140.

- Burns 2007, p. 142.

- Flood 1997, p. 73.

- Burns 2007, pp. 141–142.

- Burns 2007, pp. 148–149.

- Burns 2007, p. 147.

- Burns 2007, p. 157.

- Rudolff 2006, p. 175.

- Flood 2001, p. 114.

- Flood 2001, pp. 117–118.

- Burns 2007, pp. 176–177.

- Burns 2007, p. 187.

- Burns 2007, p. 189.

- Burns 2007, p. 190.

- Zaimeche & Ball 2005, p. 22.

- Walker 2004, pp. 36–37.

- Flood 1997, p. 67.

- Zaimeche & Ball 2005, p. 17.

- Winter & Levanoni 2004, p. 33.

- Flood 1997, p. 72.

- Charette 2003, p. 16.

- "Ibn Shatir's Sundial at Umayyad Mosque". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Selin 1997, p. 413.

- Brinner 1963, p. 155.

- Fischel 1952, p. 97.

- Berney & Ring 1996, p. 208.

- Van Leeuwen 1999, p. 95.

- Finkel 2005, p. 109.

- Kafescioǧlu 1999, p. 78.

- Van Leeuwen 1999, p. 112.

- Van Leeuwen 1999, p. 141.

- Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 123.

- Khoury 1983, pp. 13–14.

- Christian C. Sahner (17 July 2010). "A Glittering Crossroads". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- Burns 2007, p. 260.

- Darke 2010, p. 90.

- M. Lesley Wilkins (1994), "Islamic Libraries to 1920", Encyclopedia of library history, New York: Garland Pub., ISBN 0824057872, OL 1397830M, 0824057872

- Christof Galli (2001), "Middle Eastern Libraries", International Dictionary of Library Histories, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, ISBN 1579582443, OL 3623623M, 1579582443

- Darke 2010, p. 91.

- Cooke 2007, p. 12.

- Rudolff 2006, p. 194.

- Iftitah at Shaam. Mumbai: Dawat-e-Hadiyah Trust. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 9 Mar 2021 – via misbah.info.

- Platt, Barbara (2001-05-06). "Inside the Umayyad mosque". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- Protesters stage rare demo in Syria Archived 2011-11-09 at the Wayback Machine. Al-Jazeera English. 2011-03-15. Al-Jazeera.

- Syria unrest: New protests erupt across country Archived 2012-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 2011-04-01.

- "Jami' al-Umawi al-Kabir (Damascus)". ArchNet. Archived from the original on 2021-11-27. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Burns 2007, p. 112–114.

- Grafman & Rosen-Ayalon 1999, p. 8.

- "Dome of the Eagle (Qubbat ul-Nisr)". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Darke 2010, p. 94.

- Burns 2007, pp. 132, 286 (note 9).

- Enderlein 2011, p. 69.

- Burns 2007, p. 286 (note 10).

- "Domes of the Umayyad Mosque". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Minaret of Isa". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Darke 2010, p. 92.

- American Architect and Architecture 1894, p. 58.

- Rivoira 1918, p. 92.

- Palestine Exploration Fund 1897, p. 292.

- Mannheim 2001, p. 91.

- Kamal Ed-Din 2002, p. 102.

- Rudolff 2006, p. 214.

- Rudolff 2006, pp. 214–215.

- Dumper & Stanley 2007, pp. 119–126.

- Sarah Birke (2013-08-02), Damascus: What's Left, New York Review of Books, archived from the original on 2018-12-04, retrieved 2021-05-12

- Totah 2009, pp. 58–81.

- Le Strange 1890, pp. 233–234.

- Qummi, Shaykh Abbas (2005). Nafasul Mahmoom. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. p. 362.

- Nafasul Mahmoom. p. 368.

- Talmon-Heller, Daniella; Kedar, Benjamin; Reiter, Yitzhak (Jan 2016). "Vicissitudes of a Holy Place: Construction, Destruction and Commemoration of Mashhad Ḥusayn in Ascalon" (PDF). Der Islam. 93: 11–13, 28–34. doi:10.1515/islam-2016-0008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020.

- "The Prophet Eesa (Jesus)". thedawoodibohras.com. 10 Aug 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020.

- Michael Press (March 2014). "Hussein's Head and Importance of Cultural Heritage". American School of Oriental Research. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Nafasul Mahmoom. p. 367.

- Tafseer Durre Manthur Vol.6, p. 30-31.

- Tafseer Ibn Katheer, vol.9, p. 163, published in Egypt. Tafseer Durre Manthur Vol.6, p. 30-31.

- Nafasul Mahmoom. p. 381.

Bibliography

- "American Architect and Architecture". American Architect and Architecture. J. R. Osgood & Co. XLIII (945): 57–58. 1894.

- Berney, K. A.; Ring, Trudy (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 4: Middle East and Africa. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-03-6.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter Lamont (2001). Interpreting Late Antiquity: Essays on the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00598-8.

- Brinner, William M., ed. (1963). A Chronicle of Damascus, 1389–1397. University of California Press.

- Burns, Ross (2009) [1992]. The Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845119478.

- Burns, Ross (2007) [2005]. Damascus: a History (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27105-9. OCLC 648281269.

- Calcani, Giuliana; Abdulkarim, Maamoun (2003). Apollodorus of Damascus and Trajan's Column: From Tradition to Project. L'Erma di Bretschneider. ISBN 88-8265-233-5.

- Charette, François (2003). Mathematical Instrumentation in Fourteenth-Century Egypt and Syria: The Illustrated Treatise of Najm al-Dīn al-Mīṣrī. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13015-9.

- Cooke, Miriam (2007). Dissident Syria: Making Oppositional Arts Official. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4016-4.

- Darke, Diana (2010). Syria (2nd ed.). Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-314-6. OCLC 501398372.

- Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Elisséeff, Nikita (1965). "Dimashk". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume II: C–G (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 277–291. OCLC 495469475.

- Enderlein, Volkmar (2011). "Syria and Palestine: The Umayyad Caliphate". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. H. F. Ullmann. pp. 58–87. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088670.

- Fehérvári, G. (1993). "Miḥrāb". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 7–15. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02396-7.

- Fischel, Walter Joseph (1952). Ibn Khaldūn and Tamerlane: Their Historic Meeting in Damascus, 1401 A.D. (803 A.H.) A Study Based on Arabic Manuscripts of Ibn Khaldūn's "Autobiography". University of California Press.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (1997). "Umayyad Survivals and Mamluk Revivals: Qalawunid Architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus". Muqarnas. Boston: Brill. 14: 57–79. doi:10.2307/1523236. JSTOR 1523236.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2001). The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture. Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11638-9.

- George, Alain (2021). The Umayyad Mosque of Damascus: Art, Faith and Empire in Early Islam. London: Gingko Library. ISBN 9781909942455.

- Grafman, Rafi; Rosen-Ayalon, Myriam (1999). "The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus". Muqarnas. Boston: Brill. 16: 1–15. doi:10.2307/1523262. JSTOR 1523262.

- Hitti, Phillip K. (October 2002). History of Syria: Including Lebanon and Palestine. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-931956-60-4.

- Kafescioǧlu, Çiǧdem (1999). ""In The Image of Rūm": Ottoman Architectural Patronage in Sixteenth-Century Aleppo and Damascus". Muqarnas. Brill. 16: 70–96. doi:10.2307/1523266. JSTOR 1523266.

- Kamal Ed-Din, Noha, ed. (2002). The Islamic view of Jesus. Translated by Tamir Abu As-Su'ood Muhammad. Dar al-Manarah. ISBN 977-6005-08-X.

- Khoury, Philip S. (1983). Urban Notables and Arab Nationalism: The Politics of Damascus 1860-1920. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24796-9.

- Kleiner, Fred (2013). Gardner's Art through the Ages, Vol. I. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781111786441.

- Le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund

- Mannheim, Ivan (2001). Syria & Lebanon Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1-900949-90-3.

- McKenzie, Judith (2007). The architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11555-0. OCLC 873228274.

- Palestine Exploration Fund (1897). Quarterly statement. Published at the Fund's Office. (Ibn Jubayr: p. 240 ff)

- Rivoira, Giovanni Teresio (1918). Moslem Architecture: Its Origins and Development. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9788130707594.

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2014). A Short History of the Middle Ages. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442606142.

- Rudolff, Britta (2006). 'Intangible' and 'Tangible' Heritage: A Topology of Culture in Contexts of Faith (PhD). Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz.

- Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- Totah, Faedah M. (2009). "Return to the Origin: Negotiating the Modern and Unmodern in the Old City of Damascus". City & Society. 21 (1): 58–81. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01015.x.

- Walker, Bethany J. (Mar 2004). "Commemorating the Sacred Spaces of the Past: The Mamluks and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus". Near Eastern Archaeology. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 67 (1): 26–39. doi:10.2307/4149989. JSTOR 4149989. S2CID 164031578.

- Winter, Michael; Levanoni, Amalia (2004). The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian Politics and Society. Brill. ISBN 90-04-13286-4.

- Van Leeuwen, Richard (1999). Waqfs and Urban Structures: The Case of Ottoman Damascus. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11299-5.

- Wolff, Richard (2007). The Popular Encyclopedia of World Religions: A User-Friendly Guide to Their Beliefs, History, and Impact on Our World Today. Harvest House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7369-2007-0.

- Zaimeche, Salah; Ball, Lamaan (2005). Damascus. Manchester: Foundation for Science Technology and Culture.

External links

- Christian Sahner, "A Glistening Crossroads," The Wall Street Journal, 17 July 2010 Archived 30 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- For freely downloadable, high-resolution photographs of the Umayyad Mosque (for teaching, research, cultural heritage work, and publication) by archaeologists, visit Manar al-Athar Archived 2020-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Umayyad Mosque – Discover Islamic Art – Virtual Museum