HMS Astraea (1781)

HMS Astraea (or Astrea) was a 32-gun fifth rate Active-class frigate of the Royal Navy. Fabian at E. Cowes launched her in 1781, and she saw action in the American War of Independence as well as during the Napoleonic Wars. She is best known for her capture of the larger French frigate Gloire in a battle on 10 April 1795, while under the command of Captain Lord Henry Paulet. She was wrecked on 23 March 1808 off the coast of Anegada in the British Virgin Islands.

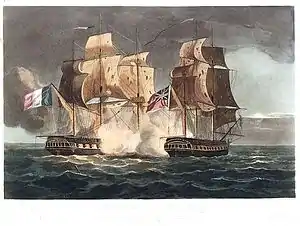

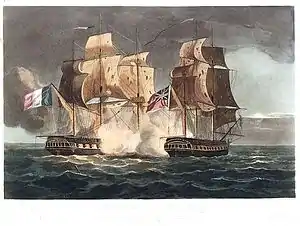

HMS Astraea captures the Gloire, a print by Thomas Whitcombe | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Astraea |

| Ordered | 7 May 1779 |

| Builder | Robert Fabian, East Cowes |

| Laid down | September 1779 |

| Launched | 24 July 1781 |

| Commissioned | July 1781 |

| Honours and awards |

|

| Fate | Wrecked off Anegada, 23 March 1808 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Active-class frigate |

| Type | Fifth Rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 703 14⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 35 ft 9 in (10.9 m) |

| Depth of hold | 12 ft (3.7 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 250 |

| Armament | |

Capture of South Carolina

Captain Matthew Squire commissioned Astraea in July 1781. On 7 October she sailed for North America.[3]

On 20 December 1782 the British 44-gun fifth rate two-decker Diomede, Captain Thomas L. Frederick and the sister frigates - Quebec, Captain Christopher Mason, and Astraea, captured the American frigate South Carolina in the Delaware River. South Carolina was attempting to dash out of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, through the British blockade. She was in the company of the brig Constance, schooner Seagrove, and the ship Hope, which had joined her for protection.

The British chased South Carolina for 18 hours and fired on her for two hours before she struck. She had a crew of about 466 men when captured, of whom she lost six killed or wounded. The British suffered no casualties.

Astraea and Quebec also captured Constance, which was carrying tobacco. Prize crews then took South Carolina and Constance to New York.

On 15 March 1783, Astraea, Vestal, and Duc de Chartres captured the ship Julius Cæsar.[4] In January 1784 Astraea was paid off.[3]

In September 1786, Astraea was commissioned under Captain Peter Rainier, Jr.[3] She proceeded to Ferrol, Madeira, and the West Indies, where she remained for three years. During this time she visited all the British islands and most of the French and Spanish colonies.

French Revolutionary Wars

From March 1793 until the spring of 1795, Astraea's captain was Robert Moorsom. After he removed to Hindostan, Captain Lord Henry Paulet (or Powlett) replaced him.[3]

Astraea was among the ships that shared in the prize money for the recapture of the ship Caldicot Castle and the French corvette Jean Bart on 28 and 30 March. (The Navy took Jean Bart into service as Arab.) The other ships were London, Colossus, Robust, Hannibal, Valiant, Thalia, Cerberus, and Santa Margarita.[5]

Astraea and Gloire

On 10 April 1795, Rear-admiral Sir John Colpoys, was cruising in the English Channel with a squadron composed of five ships of the line and three frigates, when they spotted three French frigates through a break in thick fog. London got within gunshot of one of them and opened fire, causing the French frigates to separate. Robust and Hannibal pursued two.

Astraea gave chase to a third. She caught up, and after foiling an attempt from the French ship to rake her, Astraea came alongside; the two ships exchanged broadsides for 58 minutes before the French ship struck.[6] She was the 32-gun Gloire, with 275 men aboard and armed with twenty-six 12-pounder guns on her main deck, ten 6-pounder guns and four 36-pounder carronades on her quarterdeck, and two 6-pounder guns on her forecastle.[7]

Gloire had suffered casualties of 40 killed and wounded, including her captain, Captain Beens, because the British had fired into her hull; Astraea, of 32 guns and 212 men, had only eight wounded because the French had fired high, at the mast and rigging in an attempt to cripple her.[6] For this feat Paulet received the Naval Gold Medal.[8] John Talbot, first lieutenant on Astraea, took Gloire to Britain where he received promotion to Commander and took over the 14-gun sloop-of-war Helena. Astraea shared the prize money for Gloire with London, Colossus, Valiant, Hannibal, Robust and Thalia, and shared with them in the prize money for Gentille, one of the other French frigates.[9] In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Astraea 10 April 1795" to any surviving crewmen that came forward to claim it.

The French squadron had left Brest three weeks earlier but had made only one capture, a small Spanish brig.[7] The Admiralty bought in Gloire as a 36-gun frigate and retained her name. She was already a 17-year-old ship and in March 1802 the Admiralty sold her.

Cruising

In June 1795, Captain Richard Lane took command.[3] Astraea was present at the Second Battle of Groix, which took place on 23 June 1795, off the west coast of France, but did not take part in the actual, inconclusive battle. On 10 March 1796, she set sail for Jamaica.

On 27 April 1796, Astraea brought troops to the naval squadron attacking Sainte-Lucie. The Navy contributed a force of 800 seamen under the command of Lane and Captain Ryves of Bulldog.[10] The British captured the island on 26 May 1796. Astraea was in a poor state so Rear Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the West Indies station Sir Hugh Cloberry Christian had her carry the dispatches back to Britain.[11]

On 16 February 1797, Astraea was under the command of Captain Richard Dacres when she and Plover captured the French privateer Tartare.[12]

On 1 June 1797, off The Skaw, Astraea captured the Dutch privateer Stuiver, of 10 guns and with a crew of 48 men. Stuiver was from Amsterdam and had been out 18 days, but had captured nothing.[13]

In September 1797, in the North Sea, Astraea rescued Midshipman Benjamin Clement, who would one day rise to the rank of post captain, and the crew of his jolly boat. Clement had been returning from Monarch to his ship, Nassau, in the evening but his crew were drunk and they did not reach her. By morning, the fleet was out of sight; he and his crew ended up drifting for 40 hours without food or water. By the time Astraea rescued them they were exhausted from cold and hunger,[14] but presumably were sober.

At end-February 1798 Astraea and Veteran towed General Eliott in to Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, after her crew had abandoned her.[15]

On 22 April, Astraea captured the French privateer schooner Renommée on the Dogger Bank. Renommee had a crew of 54 men and was armed with five 9-pounder guns on slides amidships so that she could deploy the guns on either side.[16] On 30 July, Astraea, Inspector, and Apollo captured the Dutch Greenlandsmen Frederick and Waachzamghheer. Then a week later they captured the Dutch Greenlandsman Liefde .[17]

In 1799, Astraea served in the North Sea while still under Dacres. On 29 March Astraea and several other vessels were in company with Latona at the capture of the galiot Neptunus.[18] Astraea was some 20 miles west of the Texel on 10 April when she captured the 14-gun French privateer lugger Marsouin after a chase of three hours. Marsouin had a crew of 58 men and was armed with 14 guns. She was a day out of Dunkirk and had taken nothing.[19]

Five days later, Astraea was among the vessels that captured Aeolus and Sex Soskendi.[20][lower-alpha 1] The next day Astraea was in company with Latona, the hired armed cutter Courier, and Cruizer when Cruizer captured the Prussian hoy Dolphin.[22]

In April 1800, Captain Peter Ribouleau commissioned Astraea.[lower-alpha 2] Between 27 April 1800, and 2 May 1800, she was at St Lucia.[3]

On 30 August 1800, Astraea was in Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren's squadron when the boats of the squadron captured the French privateer Guêpe. Astraea did share in the prize money, but does not seem to have qualified for the Naval General Service Medal.[lower-alpha 3]

In 1801, Astraea served under in the Mediterranean. Astraea was armed en flute when she took part in the landings in March at Abu Qir Bay. Fire from the French on shore wounded one seaman.[24] Because Astraea served in the navy's Egyptian campaign between 8 March 1801 and 2 September, her officers and crew qualified for the clasp "Egypt" to the Naval General Service Medal that the Admiralty authorised in 1850 for all surviving claimants.[lower-alpha 4]

Napoleonic Wars

Captain James Carthew commissioned Astraea in April 1805 for the Downs.[3] On 21 October, Astraea was among the British vessels sharing in the capture of the Anna Wilhelmine.[26] Captain James Dunbar replaced Carthew in February 1806.[3]

On 1 December Astraea limped into Elsinore, Denmark, with water in her hold and her masts gone. She had experienced bad weather near the Skaws and then grounded on a shoal some three miles off the island of Anholt in the Kattegat. One of Astraea's passengers, Lord Hutchinson, had gone ashore indisposed. Dunbar had to throw her guns and stores overboard and cut away her masts before she floated free. He then had a mizzen-jury mast erected, which enabled her to sail the 25 miles to Elsinore.[27]

August 1807 was a busy month for Astraea. On the 19th she and Agamemnon captured two Danish merchant vessels: Two Sisters and Three Brothers.[28] One week later, Astraea, Comus, and Surveillante captured the Danish vessel Fama.[29] That same day Astraeacaptured the Danish merchant vessel Anna Dorothea.[30] Also during the month, Astraea, Agamemnon, and Cruizer shared in the capture of the Danish merchant vessels Anne and, Catherine, Anne and Margaret, and Three Brothers.[31]

In November 1807 Captain Edmund Heywood took command of Astraea as she was fitting out at Chatham for the West Indies.[3] On 14 December, Astraea captured the French privateer lugger Providence. At the time of the capture, the sloop-of-war Royalist had joined the pursuit and gun-brigs Wrangler and Tickler were in sight.[32] Providence carried 14 guns and a crew of 52 men.[26]

Loss

In 1808, Astraea escorted the mail packet ship Prince Earnest past the danger of Caribbean privateers. Heywood, thinking that Anegada was Puerto Rico, wrecked upon the deadly horseshoe reef on 23 March. All but four of her crew survived, either by making it to the island or to Virgin Gorda.[lower-alpha 5] Two days after the wreck, the 22-gun sloop-of-war and former French privateer St Christopher (also known as the St Kitt's), arrived and rescued the crew. The two 32-gun frigates Jason and Galatea, and the sloop-of-war Fawn arrived later, and engaged in salvage attempts. The British abandoned the wreck on 24 June.[34] Many of the crew went on to serve aboard Favourite.[35]

As was usual, Captain Heywood, his officers and crew, were subject to a court martial for the loss of his ship. This took place on 11 June 1808 on Ramillies in Carlisle Bay, Barbados. The court held that the ship foundered due to an "extraordinary weather current", and exonerated Heywood.[33] The court martial held:"... having heard the narrative thereof by Captain Edmund Heywood, together with explanations given by himself and also by Mr. Allan McLean, the master of the said ship, and having fully completed the inquiry, and maturely and deliberately weighed and considered the whole thereof, the court is of opinion that the loss was occasioned by an extraordinary weather current having set the ship nearly two degrees to the eastwards of the reckoning of all the officers on board ... and that no blame is attributable to Captain Heywood, his officers, and ship's company."

Wreck site

The British Virgin Islands have honoured Astraea with a stamp. The reason is that in 1967 Bert Kilbride, Her Majesty's Receiver of Wreck in the British Virgin Islands, rediscovered her. Subsequently, some items were salvaged, but not the heavy cannon. However, conditions at the reef remain treacherous; tourists rarely dive the wreck.

Notes

- Dacres' share of the prize money, which paid in March 1812, was £58 7s 6+3⁄4d; a seaman's share was 4s 8+1⁄2d, or less than 5% of what Dacres received.[21]

- For more on Captain Peter Ribouleau see: O'Byrne, William R. (1849). . A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray.

- Seamen and troops each received 1s 9+1⁄2d in prize money.[23]

- A first-class share of the prize money awarded in April 1823 was worth £34 2s 4d; a fifth-class share, that of a seaman, was worth 3s 11+1⁄2d. The amount was small as the total had to be shared between 79 vessels and the entire army contingent.[25] Note

- Two were killed when a gun burst while firing a distress signal, and two drowned. Later, one seaman was hanged for mutinous conduct.[33]

Citations

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 237.

- "No. 21077". The London Gazette. 15 March 1850. pp. 791–792.

- "NMM, vessel ID 380295" (PDF). Warship Histories, vol v. National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- "No. 12804". The London Gazette. 14 November 1786. p. 553.

- "No. 13956". The London Gazette. 29 November 1796. pp. 1159–1160.

- "The Right Hon. Lord Henry Paulet". Annual Biography and Obituary. 1832. p. 48.

- "No. 13770". The London Gazette. 14 April 1795. p. 393.

- Royal Navy (1850). The Navy List. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 296. OCLC 1604131.

- "No. 13810". The London Gazette. 1 September 1795. p. 907.

- "No. 13903". The London Gazette. 21 June 1796. p. 593.

- "No. 13908". The London Gazette. 4 July 1796. p. 640.

- "No. 14077". The London Gazette. 14 October 1797. p. 1233.

- "No. 14019". The London Gazette. 13 June 1797. p. 559.

- Marshall (1828), Supplement, Part 2, p. 392.

- Lloyd's List No. 2984.

- "No. 15017". The London Gazette. 19 May 1798. p. 424.

- "No. 15267". The London Gazette. 14 June 1800. p. 668.

- "No. 15404". The London Gazette. 5 September 1801. p. 1097.

- "No. 15124". The London Gazette. 13 April 1799. p. 351.

- "No. 16582". The London Gazette. 10 March 1812. p. 477.

- "No. 16580". The London Gazette. 3 March 1812. p. 432.

- "No. 15427". The London Gazette. 14 November 1801. p. 1374.

- "No. 15434". The London Gazette. 8 December 1801. p. 1466.

- "No. 15362". The London Gazette. 5 May 1801. pp. 496–497.

- "No. 17915". The London Gazette. 3 April 1823. p. 633.

- "No. 16096". The London Gazette. 15 December 1807. p. 1686.

- Wilson & Randolph (1862), Vol. 1, pp. 3–6.

- "No. 16630". The London Gazette. 4 August 1812. p. 1509.

- "No. 16582". The London Gazette. 10 March 1812. p. 478.

- "No. 16600". The London Gazette. 5 May 1812. p. 862.

- "No. 16720". The London Gazette. 13 April 1813. p. 753.

- "No. 16406". The London Gazette. 18 September 1810. p. 1470.

- Hepper (1994), p. 122.

- Naval Chronicle, Vol. 20, p. 44.

- The Annual biography and obituary, Volume 21, p. 445.

References

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Hepper, David J. (1994). British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail, 1650-1859. Rotherfield: Jean Boudriot. ISBN 0-948864-30-3.

- Marshall, John (2007) Royal Naval Biography; Or Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-Officers, Superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired Captains, Post-Captains and Commanders... (Kessinger). ISBN 1-4326-4615-X

- Urban, Sylvanus (1832). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 102, pt. 1. F. Jefferies.

- Wilson, Sir Robert Thomas and Herbert Randolph (1862) Life of General Sir Robert Wilson ...: from autobiographical memoirs, journals, narratives, correspondence. (J. Murray).

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1844157006.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

External links

- Tage W. Blytmann's comprehensive site dedicated to HMS Astraea

- Wreck Diving in The BVI

- Michael Phillip's Ships of the Old Navy

This article includes data released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported UK: England & Wales Licence, by the National Maritime Museum, as part of the Warship Histories project.