Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway

The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR), also known as the Hampstead Tube, was a railway company established in 1891 that constructed a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London.[note 1] Construction of the CCE&HR was delayed for more than a decade while funding was sought. In 1900 it became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes. The UERL quickly raised the funds, mainly from foreign investors. Various routes were planned, but a number of these were rejected by Parliament. Plans for tunnels under Hampstead Heath were authorised, despite opposition by many local residents who believed they would damage the ecology of the Heath.

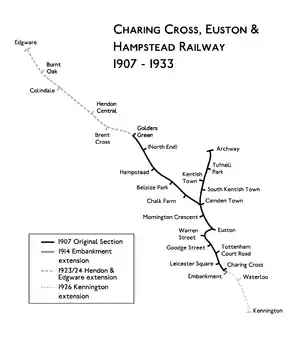

When opened in 1907, the CCE&HR's line served 16 stations and ran for 7.67 miles (12.34 km)[1] in a pair of tunnels between its southern terminus at Charing Cross and its two northern termini at Archway and Golders Green. Extensions in 1914 and the mid-1920s took the railway to Edgware and under the River Thames to Kennington, serving 23 stations over a distance of 14.19 miles (22.84 km).[1] In the 1920s the route was connected to another of London's deep-level tube railways, the City and South London Railway (C&SLR), and services on the two lines were merged into a single London Underground line, eventually called the Northern line.

Within the first year of opening, it became apparent to the management and investors that the estimated passenger numbers for the CCE&HR and the other UERL lines had been over-optimistic. Despite improved integration and cooperation with the other tube railways, and the later extensions, the CCE&HR struggled financially. In 1933 the CCE&HR and the rest of the UERL were taken into public ownership. Today, the CCE&HR's tunnels and stations form the Northern line's Charing Cross branch from Kennington to Camden Town, the Edgware branch from Camden Town to Edgware, and the High Barnet branch from Camden Town to Archway.

Establishment

Origin, 1891–1893

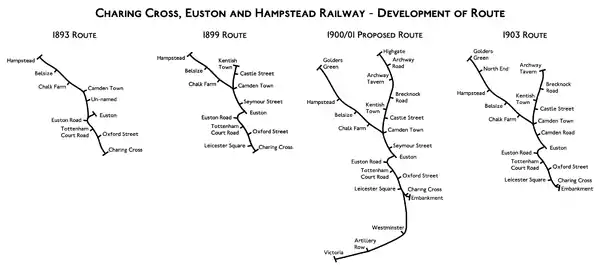

In November 1891, notice was given of a private bill that would be presented to Parliament for the construction of the Hampstead, St Pancras & Charing Cross Railway (HStP&CCR).[2] The railway was planned to run entirely underground from Heath Street, Hampstead to Strand in Charing Cross. The route was to run beneath Hampstead High Street, Rosslyn Hill, Haverstock Hill and Chalk Farm Road to Camden Town and then under Camden High Street and Hampstead Road to Euston Road. The route then continued south, following Tottenham Court Road, Charing Cross Road and King William Street (now William IV Street) to Agar Street adjacent to Strand. North of Euston Road, a branch was to run eastwards from the main alignment under Drummond Street to serve the main line stations at Euston, St Pancras and King's Cross.[3] Stations were planned at Hampstead, Belsize Park, Chalk Farm, Camden Town, Seymour Street (now part of Eversholt Street), Euston Road, Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Street, Agar Street, Euston and King's Cross.[3] Although a decision had not been made between the use of cable haulage or electric traction as the means of pulling the trains, a power station was planned on Chalk Farm Road close to the London and North Western Railway's Chalk Farm station (later renamed Primrose Hill) which had a coal depot for deliveries.[3]

The promoters of the HStP&CCR were inspired by the recent success of the City and South London Railway (C&SLR), the world's first deep-tube railway. This had opened in November 1890 and had seen large passenger numbers in its first year of operation.[note 2] Bills for three similarly inspired new underground railways were also submitted to Parliament for the 1892 legislative session, and, to ensure a consistent approach, a Joint Select Committee was established to review the proposals. The committee took evidence on various matters regarding the construction and operation of deep-tube railways, and made recommendations on the diameter of tube tunnels, method of traction, and the granting of wayleaves. After preventing the construction of the branch beyond Euston, the Committee allowed the HStP&CCR bill to proceed for normal parliamentary consideration. The rest of the route was approved and, following a change of the company name, the bill received royal assent on 24 August 1893 as the Charing Cross, Euston, and Hampstead Railway Act, 1893.[5]

Search for financing, 1893–1903

Although the company had permission to construct the railway, it still had to raise the capital for the construction works. The CCE&HR was not alone; four other new tube railway companies were looking for investors – the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), the Waterloo & City Railway (W&CR) and the Great Northern & City Railway (GN&CR) (the three other companies that put forward bills in 1892) and the Central London Railway (CLR, which had received assent in 1891).[note 3] Only the W&CR, which was the shortest line and was backed by the London and South Western Railway with a guaranteed dividend, was able to raise its funds without difficulty.[7] For the CCE&HR and the rest, much of the remainder of the decade saw a struggle to find investors in an uninterested market. A share offer in April 1894 had been unsuccessful and in December 1899 only 451 out of the company's 177,600 £10 shares had been part sold to eight investors.[8]

Like most legislation of its kind, the act of 1893 imposed a time limit for the compulsory purchase of land and the raising of capital.[note 4] To keep the powers granted by the act alive, the CCE&HR submitted a series of further bills to Parliament for extensions of time. Extensions were granted by the Charing Cross Euston and Hampstead Railway Acts, 1897,[9] 1898,[10] 1900,[11] and 1902.[12]

A contractor was appointed in 1897, but funds were not available and no work was started.[13] In 1900, foreign investors came to the rescue of the CCE&HR: American financier Charles Yerkes, who had been lucratively involved in the development of Chicago's tramway system in the 1880s and 1890s, saw the opportunity to make similar investments in London. Starting with the purchase of the CCE&HR in September 1900 for £100,000, he and his backers purchased a number of the unbuilt tube railways, and the operational but struggling Metropolitan District Railway (MDR).[note 5]

With the CCE&HR and the other companies under his control, Yerkes established the UERL to raise funds to build the tube railways and to electrify the steam-operated MDR. The UERL was capitalised at £5 million with the majority of shares sold to overseas investors.[note 6] Further share issues followed, which raised a total of £18 million (equivalent to approximately £2.06 billion today)[15] to be used across all of the UERL's projects.[note 7]

Deciding the route, 1893–1903

While the CCE&HR raised money, it continued to develop the plans for its route. On 24 November 1894, a bill was announced to purchase additional land for stations at Charing Cross, Oxford Street, Euston and Camden Town.[17] This was approved as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1894 on 20 July 1895.[18] On 23 November 1897, a bill was announced to change the route of the line at its southern end to terminate under Craven Street on the south side of Strand.[19] This was enacted as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1898 on 25 July 1898.[10]

On 22 November 1898, the CCE&HR published another bill to add an extension and to modify part of the route.[20] The extension was a branch from Camden Town to Kentish Town where a new terminus was planned as an interchange with the Midland Railway's Kentish Town station. Beyond the terminus, the CCE&HR line was to come to the surface for a depot on vacant land to the east of Highgate Road (occupied today by the Ingestre Road Estate). The modification changed the Euston branch by extending it northwards from Euston to connect to the main route at the south end of Camden High Street. The section of the main route between the two ends of the loop was omitted. Included in the bill were powers to purchase a site in Cranbourn Street for an additional station (Leicester Square). It received royal assent as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1899 on 9 August 1899.[21]

On 23 November 1900, the CCE&HR announced its most wide-ranging modifications to the route. Two bills were submitted to Parliament, referred to as No. 1 and No. 2. Bill No. 1 proposed the continuation of the railway north from Hampstead to Golders Green, the purchase of land and properties for stations and the construction of a depot at Golders Green. Also proposed were minor adjustments to route alignments previously approved.[22][23] Bill No. 2 proposed two extensions: from Kentish Town to Brecknock Road, Archway Tavern, Archway Road and Highgate in the north and from Charing Cross to Parliament Square, Artillery Row and Victoria station in the south.[24][25]

The extension to Golders Green would take the railway out of the urban and suburban areas and into open farmland. While this provided a convenient site for the CCE&HR's depot[note 8] it is believed that underlying the decision was Yerkes' plan to profit from the sale of development land previously purchased in the area that would rise in value when the railway opened.[note 9]

The CCE&HR's two bills were submitted to Parliament at the same time as a large number of other bills for underground railways in the capital.[note 10] As it had done in 1892, Parliament established a joint committee under Lord Windsor to review the bills.[28] By the time the committee had produced its report, the parliamentary session was almost over and the promoters of the bills were asked to resubmit them for the following 1902 session.[29] Bills No. 1 and No. 2 were resubmitted in November 1901 together with a new bill – bill No. 3. The new bill modified the route of the proposed extension to Golders Green and added a short extension running beneath Charing Cross main line station to the Victoria Embankment where it would provide an interchange with the existing MDR station (then called Charing Cross).[30]

The bills were again examined by a joint committee, this time under Lord Ribblesdale.[note 11] The sections which dealt with the proposed north-eastern extension from Archway Tavern to Highgate and the southern extension from Charing Cross to Victoria were deemed to not comply with parliamentary standing orders and were struck-out.[32][note 12]

Hampstead Heath controversy

A controversial element of the CCE&HR's plans was the extension of the railway to Golders Green. The route of the tube tunnels took the line under Hampstead Heath and strong opposition was raised, concerned about the effect that the tunnels would have on the ecology of the Heath. The Hampstead Heath Protection Society claimed that the tunnels would drain the sub-soil of water and the vibration of passing trains would damage trees. Taking its lead from the Society's objections, The Times published an alarmist article on 25 December 1900 claiming that "a great tube laid under the heath will, of course, act as a drain; and it is quite likely that the grass and gorse and trees on the Heath will suffer from the loss of moisture ... Moreover, it seems to be established beyond question that the trains passing along these deep-laid tubes shake the earth to its surface, and the constant jar and quiver will probably have a serious effect upon the trees by loosening their roots."[34]

In fact, the tunnels were to be excavated at a depth of more than 200 feet (61 m) below the surface,[32] the deepest of any on the London Underground.[35] In his presentation to the joint committee, the CCE&HR's counsel disparagingly refuted the objections: "Just see what an absurd thing! Disturbance of the water when we are 240 feet down in the London clay – about the most impervious thing you can possibly find; almost more impervious than granite rock! And the vibration on this railway is to shake down timber trees! Could anything be more ludicrous than to waste the time of the Committee in discussing such things presented by such a body!"[36]

A second railway company, the Edgware & Hampstead Railway (E&HR), also had a bill before Parliament which proposed tunnels beneath the Heath as part of its planned route between Edgware and Hampstead.[37] The E&HR had planned to connect to the CCE&HR at Hampstead but, to avoid the needless duplication of tunnels between Golders Green and Hampstead, the two companies agreed that the E&HR would instead connect to the CCE&HR at Golders Green.[38]

The Metropolitan Borough of Hampstead had initially objected to the line but gave consent on the condition that a station be constructed between Hampstead and Golders Green to provide access for visitors to the Heath. A new station was added to the plans at the northern edge of the Heath at North End where it could also serve a new residential development planned for the area.[note 13] Once Parliament was satisfied that the extension would not damage the Heath, the CCE&HR bills jointly received royal assent on 18 November 1902 as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1902.[12] On the same date, the E&HR bill received its assent as the Edgware and Hampstead Railway Act, 1902.[12]

Construction, 1902–1907

With the funds available from the UERL and the route decided, the CCE&HR started site demolitions and preparatory works in July 1902. On 21 November 1902, the CCE&HR published another bill which sought compulsory purchase powers for additional buildings for its station sites, planned the take-over of the E&HR and abandoned the permitted but redundant section of the line from Kentish Town to the proposed depot site near Highgate Road.[39][note 14] This bill was approved as the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1903 on 21 July 1903.[41]

Tunnelling began in September 1903.[35] Stations were provided with surface buildings designed by architect Leslie Green in the UERL house-style.[42] This consisted of two-storey steel-framed buildings faced with red glazed terracotta blocks with wide semi-circular windows on the upper floor.[note 15] Each station was provided with two or four lifts and an emergency spiral staircase in a separate shaft.[note 16]

While construction proceeded, the CCE&HR continued to submit bills to Parliament. The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1904, which received assent on 22 July 1904, granted permission to buy additional land for the station at Tottenham Court Road, for a new station at Mornington Crescent and for changes at Charing Cross.[46][47] The Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway Act, 1905 received assent on 4 August 1905.[48][49] It dealt mainly with the acquisition of the subsoil under part of the forecourt of the South Eastern Railway's Charing Cross station so that the CCE&HR's station could be excavated during the 3 months closure following the recent roof collapse.[note 17]

The sale of the building land at North End to conservationists to form the Hampstead Heath extension in 1904, meant a reduction in the number of residents who might use the station there. Work continued below ground at a reduced pace, and the platform tunnels and some passenger circulation tunnels were excavated, but North End station was abandoned in 1906 before the lift and stair shafts were dug and before a surface building was constructed.[51]

Tunnelling was completed in December 1905, after which work continued on the construction of the station buildings and the fitting-out of the tunnels with tracks and signalling equipment.[35] As part of the UERL group, the CCE&HR obtained its electricity from the company's Lots Road Power Station, originally built for the electrification of the MDR; the proposed Chalk Farm generating station was not built. The final section of the approved route between Charing Cross and the Embankment was not constructed, and the southern terminus on opening was Charing Cross. After a period of test running, the railway was ready to open in 1907.

Opening

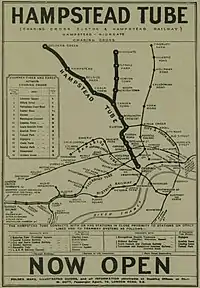

The CCE&HR was the last of the UERL's three tube railways to open and was advertised as the "Last Link".[52] The official opening on 22 June 1907 was made by David Lloyd George, President of the Board of Trade, after which the public travelled free for the rest of the day.[53][54] From its opening, the CCE&HR was generally known by the abbreviated names Hampstead Tube or Hampstead Railway and the names appeared on the station buildings and on contemporary maps of the tube lines.[55][56]

The railway had stations at:

- Charing Cross

- Leicester Square

- Oxford Street (now Tottenham Court Road)

- Tottenham Court Road (now Goodge Street)

- Euston Road (now Warren Street)

- Euston

- Mornington Crescent

- Camden Town

Golders Green branch

Highgate branch

- South Kentish Town (closed 1924)[57]

- Kentish Town

- Tufnell Park

- Highgate (now Archway)

The service was provided by a fleet of carriages manufactured for the UERL by the American Car and Foundry Company and assembled at Trafford Park in Manchester.[43] These carriages were built to the same design used for the BS&WR and the GNP&BR and operated as electric multiple unit trains without the need for separate locomotives. Passengers boarded the trains via folding lattice gates at each end of cars which were operated by Gate-men who rode on the outside platform and announced station names as trains arrived. The design became known on the Underground as the 1906 stock or Gate stock.

Co-operation and consolidation, 1907–1910

Despite the UERL's success in financing and constructing the Hampstead Railway in only seven years, its opening was not the financial success that had been expected. In the Hampstead Tube's first twelve months of operation it carried 25 million passengers, just half of the 50 million that had been predicted during the planning of the line.[58] The UERL's pre-opening predictions of passenger numbers for its other new lines proved to be greatly over-optimistic, as did the improvement in passenger numbers expected on the newly electrified MDR – in each case achieving only around fifty per cent of their targets.[note 18]

The lower than expected passenger numbers were partly due to competition between the tube and sub-surface railway companies, but the introduction of electric trams and motor buses, replacing slower, horse-drawn road transport, took a large number of passengers away from the trains. The problem was not limited to the UERL; all of London's seven tube lines and the sub-surface MDR and Metropolitan Railway were affected to a degree and the reduced revenues generated from the lower numbers of passengers made it difficult for the UERL and the other railways to pay back the capital borrowed and pay dividends to shareholders.[59]

In an effort to improve the financial situation, the UERL together with the C&SLR, the CLR and the GN&CR began, from 1907, to introduce fare agreements. From 1908, they began to present themselves through common branding as the Underground.[59] The W&CR was the only tube railway that did not participate in the arrangement as it was owned by the mainline London and South Western Railway.

The UERL's three tube railway companies were still legally separate entities with their own management and shareholder and dividend structures. There was duplicated administration between the three companies and, to streamline the management and reduce expenditure, the UERL announced a bill in November 1909 that would merge the Hampstead Tube, the Piccadilly Tube and the Bakerloo Tube into a single entity, the London Electric Railway (LER), although the lines retained their own individual branding.[60][note 19] The bill received assent on 26 July 1910 as the London Electric Railway Amalgamation Act 1910 (10 Edw. 7. & 1 Geo. 5. c. xxxii).[61]

Extensions

Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extent of route in 1926 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Embankment, 1910–1914

In November 1910, the LER published notice of a bill to revive the unused 1902 permission to continue the line from Charing Cross to Embankment.[62] The extension was planned as a single tunnel, running in a loop under the Thames, connecting the ends of the two existing tunnels. Trains were to run in one direction around the loop stopping at a single-platform station constructed to provide an interchange with the BS&WR and MDR at Embankment station.[63][note 20] The bill received assent as the London Electric Railway Act, 1911 on 2 June 1911.[64] The loop was constructed from a large excavation north-west of the MDR station and was connected to the sub-surface line with escalators.[63] The station opened on 6 April 1914[57] as:

- Charing Cross (Embankment) (now Embankment)[note 21]

Hendon and Edgware, 1902–1924

In the decade after the E&HR received royal assent for its route from Edgware to Hampstead, the company continued to search for finance and revised its plans in conjunction both with the CCE&HR and a third railway company, the Watford & Edgware Railway (W&ER) which had plans to build a line linking the E&HR to Watford.

Following the enactment of the Watford and Edgware Railway Act, 1906,[65] the W&ER briefly took over the powers of the E&HR to construct the line from Golders Green to Edgware. Struggling to find funds, the W&ER attempted a formal merger with the E&HR through a bill submitted to Parliament in 1906,[66] with the intention of constructing and operating the whole of the route from Golders Green to Watford as a light railway but the bill was rejected by Parliament and, when the W&ER's powers lapsed, control returned to the CCE&HR.[67]

The E&HR company had remained in existence and had obtained a series of acts to preserve and develop its plans. The Edgware and Hampstead Railway Acts, 1905,[68] 1909[69] and 1912[70] granted extensions of time, approved changes to the route, gave permissions for viaducts and a tunnel and allowed the closure and re-routeing of roads to be crossed by the railway's tracks. It was intended that the CCE&HR would provide and operate the trains and this was formalised by the London Electric Railway Act, 1912,[70] which approved the LER's take over of the E&HR.

No immediate effort was made to start the works and they were postponed indefinitely when World War I started. With wartime restrictions in place, construction work for the railway was prevented. Yearly extensions to the earlier E&HR acts were granted under special wartime powers each year from 1916 until 1922, giving a final date by which compulsory purchases had to be made of 7 August 1924.[71] Although the permissions had been maintained, the UERL could not raise the money needed for the works. Construction costs had increased considerably during the war years and the returns produced by the company could not cover the cost of repaying loans.[72]

The project was made possible when the government introduced the Trade Facilities Act 1921 by which the Treasury underwrote loans for public works as a means of alleviating unemployment. With this support, the UERL raised the funds and work began on extending the Hampstead tube to Edgware. The UERL group's Managing Director/Chairman, Lord Ashfield, ceremonially cut the first sod to begin the works at Golders Green on 12 June 1922.[73]

The extension crossed farmland, meaning it could be constructed on the surface more easily and cheaply than a deep tube line below the surface. A viaduct was constructed across the Brent valley and a short section of tunnel was required at The Hyde, Hendon. Stations were designed in a suburban pavilion style by the UERL's architect Stanley Heaps.[74] The first section opened on 19 November 1923[57] with stations at:

- Brent (now Brent Cross)

- Hendon Central

The remainder of the extension opened on 18 August 1924[57] with stations at:

Kennington, 1922–1926

On 21 November 1922, the LER announced a bill for the 1923 parliamentary session. It included the proposal to extend the line from its southern terminus[note 22] to the C&SLR's station at Kennington where an interchange would be provided.[75] The bill received royal assent as the London Electric Railway Act, 1923 on 2 August 1923.[76]

The work involved the rebuilding of the below ground parts of the CCE&HR's former terminus station to enable through running and the loop tunnel was abandoned. Tunnels were extended under the Thames to Waterloo station and then to Kennington where two additional platforms were constructed to provide the interchange to the C&SLR. Immediately south of Kennington station, the CCE&HR tunnels connected to those of the C&SLR. The new service was opened on 13 September 1926 to coincide with the opening of the extension of the C&SLR to Morden.[57] The Charing Cross to Kennington link had stations at:

The C&SLR had been under the control of the UERL since its purchase by the group in 1913.[note 23] An earlier connection between the CCE&HR and the C&SLR had been opened in 1924 linking the C&SLR's station at Euston with the CCE&HR's at Camden Town. With the opening of the Kennington extension, the two railways began to operate as an integrated service using the newly built Standard Stock trains. On tube maps the combined lines were shown in a single colour although the separate names continued in use into the 1930s.[note 24]

Move to public ownership, 1923–1933

Despite improvements made to other parts of the network,[note 25] the Underground railways were still struggling to make a profit. The UERL's ownership of the highly profitable London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) since 1912 had enabled the UERL group, through the pooling of revenues, to use profits from the bus company to subsidise the less profitable railways.[note 26] However, competition from numerous small bus companies during the early 1920s eroded the profitability of the LGOC and had a negative impact on the profitability of the whole UERL group.

In an effort to protect the UERL group's income Lord Ashfield lobbied the government for regulation of transport services in the London area. Starting in 1923, a series of legislative initiatives were made in this direction, with Ashfield and Labour London County Councillor (later MP and Minister of Transport) Herbert Morrison, at the forefront of debates as to the level of regulation and public control under which transport services should be brought. Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.[80] After seven years of false starts, a bill was announced at the end of 1930 for the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a public corporation that would take control of the UERL, the Metropolitan Railway and all bus and tram operators within an area designated as the London Passenger Transport Area.[81] The Board was a compromise – public ownership but not full nationalisation – and came into existence on 1 July 1933. On this date, the LER and the other Underground companies were liquidated.[82]

Legacy

Finding a suitable name for the combined CCE&HR and C&SLR routes proved a challenge for the LPTB and a number of variations were used including Edgware, Morden & Highgate Line in 1933 and Morden-Edgware Line in 1936.[83] In 1937, Northern line was adopted in preparation for the uncompleted Northern Heights plan.[83][84] Today, the Northern line is the busiest on the London Underground system, carrying 206.7 million passengers annually,[84] a level of usage which led it to be known as the Misery line during the 1990s due to overcrowding and poor reliability.[85][86]

Notes and references

Notes

- A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level.

- In its first year of operation the C&SLR carried 5.1 million passengers.[4]

- The Central London Railway received assent on 5 August 1891, the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway Act received assent on 28 March 1893, the Waterloo and City Railway Act received assent on 8 March 1893 and the Great Northern & City Railway Act received assent on 28 June 1892.[6]

- Time limits were included in such legislation to encourage the railway company to complete the construction of its line as quickly as possible. They also prevented unused permissions acting as an indefinite block to other proposals.

- Between September 1900 and March 1902, Yerkes' consortium purchased the CCE&HR (September 1900), the MDR (March 1901), the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway, the Great Northern and Strand Railway (both September 1901) and the BS&WR (March 1902).[14]

- Yerkes was Chairman of the UERL with the other main investors being investment banks Speyer Brothers (London), Speyer & Co. (New York City) and Old Colony Trust Company (Boston).[14]

- Like many of Yerkes' schemes in the United States, the structure of the UERL's finances was highly complex and involved the use of novel financial instruments linked to future earnings. Over-optimistic expectations of passenger usage meant that many investors failed to receive the returns expected.[16]

- The site adjacent to Highgate Road was smaller than the site at Golders Green.

- Before construction of the railway began, land in Golders Green was valued at £200 - £300 per acre. After work started, the value increased to £600 - £700 per acre.[26]

- In addition to bills for extensions to existing tube railways, bills for seven new tube railways were submitted to Parliament in 1901.[27] While a number received royal assent, none were built.

- The Ribblesdale committee examined bills for tube railways on a north–south alignment. Lord Windsor headed a separate committee to examine bills for tube railways on an east–west alignment.[31]

- Rules and procedures known as standing orders existed covering the presentation of private bills to Parliament and a failure to comply with these could result in a bill's rejection. Standing orders for railway bills included requirements to publish a notice of intention to submit the bill in the London Gazette in the November of the preceding year, to submit maps and plans of the route to various interested parties, to provide an estimate of the cost and to deposit 5% of the estimated cost into the Court of Chancery.[33]

- North End station has also been known as Bull and Bush due to its proximity to a pub of that name.

- Included in the bill was a proposal to formally transfer the CCE&HR's powers to another of the UERL's railways, the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway. With similar proposals included in a bill for the BS&WR, the UERL's other tube line, this would have merged the three separate companies into one called the Underground Consolidated Electric Railways Company. The proposal was rejected by Parliament.[40]

- Three CCE&HR stations were exceptions to Leslie Green's usual station design: Golders Green had a brick-built station building, Tottenham Court Road had a ticket hall under the street accessed by pedestrian subways and had no building of its own and Charing Cross used an entrance built into the side of the main line station building.

- The lifts, supplied by American manufacturer Otis,[43] were installed in pairs within 23 ft diameter shafts.[44] The number of lifts depended on the expected passenger demand at the stations, for example, Hampstead has four lifts but Chalk Farm and Mornington Crescent have two each.[45]

- Previous CCE&HR acts had already obtained permission for the use of most of the subsoil of the forecourt and this act extended the permission to the whole of its area.[50]

- The UERL had predicted 35 million passengers for the BS&WR and 60 million for the GNP&BR in their first year of operation but achieved 20.5 and 26 million respectively. For the MDR it had predicted an increase to 100 million passengers after electrification but achieved 55 million.[58]

- The merger was carried out by transferring the assets of the CCE&HR and the BS&WR to the GNP&BR and renaming the GNP&BR as the London Electric Railway.

- Part of the loop remains in use today as the sharply curved northbound Northern line platform.

- The BS&WR and MDR parts of the station had had different names. The BS&WR section was renamed Charing Cross (Embankment) to match the CCE&HR but the MDR part continued to be called just Charing Cross.[57]

- In a three-way renaming on 9 May 1915, the CCE&HR's terminus station Charing Cross (Embankment) was renamed Charing Cross, the CCE&HR's Charing Cross station (which had briefly been named Charing Cross (Strand)) was renamed Strand and the GNP&BR's Strand station was renamed Aldwych.[57]

- The UERL purchased both the C&SLR and Central London Railway on 1 January 1913, making the payments in its own shares.[77]

- The combined route was shown in black as it is today with the line names given as Hampstead and Highgate Line and City & South London Railway.[78]

- During World War I, the BS&WR was extended from Paddington to Watford Junction. Post war; the extension of the CLR from Wood Lane to Ealing Broadway was opened in 1920.[57]

- By having a virtual monopoly of bus services, the LGOC was able to make large profits and pay dividends far higher than the underground railways ever had. In 1911, the year before its take over by the UERL, the dividend had been 18 per cent.[79]

References

- Length of line calculated from distances given at "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Northern line, Layout". Clive D. W. Feather. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- "No. 26226". The London Gazette. 24 November 1891. pp. 6324–6326.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 58.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 321.

- "No. 26435". The London Gazette. 25 August 1893. p. 4825.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 47, 56, 57, 60.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 57 & 112.

- "New London Electric Railway Scheme". The Times (36252): 6. 20 September 1900. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "No. 26859". The London Gazette. 4 June 1897. p. 3128.

- "No. 26990". The London Gazette. 26 July 1898. p. 4506.

- "No. 27197". The London Gazette. 29 May 1900. p. 3404.

- "No. 27497". The London Gazette. 21 November 1902. p. 7533.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 184.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 118.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 170–172.

- "No. 26461". The London Gazette. 24 November 1893. pp. 6859–6860.

- "No. 26535". The London Gazette. 24 July 1894. p. 4214.

- "No. 26913". The London Gazette. 23 November 1897. pp. 6827–6829.

- "No. 27025". The London Gazette. 22 November 1898. pp. 7134–7136.

- "No. 27107". The London Gazette. 11 August 1899. pp. 5011–5012.

- "No. 27249". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 November 1900. pp. 7613–7616.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 94.

- "No. 27249". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 November 1900. pp. 7491–7493.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 95.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 172–173 & 187.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 92.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 93.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 111.

- "No. 27379". The London Gazette. 22 November 1901. pp. 7732–7734.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 131.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 137.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 41.

- "The Tunnel Under Hampstead Heath". The Times. London. 25 December 1900. p. 9. Retrieved 31 August 2008. (registration required). Quoted, with slight differences, in Wolmar 2005, pp. 184–185

- Wolmar 2005, p. 185.

- Quoted in Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 137

- "No. 27380". The London Gazette. 26 November 1901. pp. 8200–8202.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 138.

- "No. 27497". The London Gazette. 21 November 1902. pp. 7642–7644.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 203 & 215.

- "No. 27580". The London Gazette. 24 July 1903. p. 4668.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 175.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 188.

- Connor 1999, plans of stations.

- "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Lifts and Escalators". Clive D. W. Feathers. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- "No. 27618". The London Gazette. 20 November 1903. pp. 7195–7196.

- "No. 27699". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 July 1904. pp. 4827–4828.

- "No. 27737". The London Gazette. 22 November 1904. pp. 7774–7776.

- "No. 27825". The London Gazette. 8 August 1905. pp. 5447–5448.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 237.

- Connor 1999, pp. 14–17.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 250.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 186.

- Report of the opening - "Opening of the Hampstead Tube". The Times. London. 24 June 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 31 August 2008. (registration required).

- Photograph of Euston Road station (now Warren Street), 1907 – London Transport Museum photographic archive. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- 1908 tube map Archived 23 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine – A History of the London Tube Maps. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- Rose 1999.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 191.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 282–283.

- "No. 28311". The London Gazette. 23 November 1909. pp. 8816–8818.

- "No. 28402". The London Gazette. 29 July 1910. pp. 5497–5498.

- "No. 28439". The London Gazette. 22 November 1910. pp. 8408–8411.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 271.

- "No. 28500". The London Gazette. 2 June 1911. p. 4175.

- "No. 27938". The London Gazette. 7 August 1906. pp. 5453–5454.

- "No. 27971". The London Gazette. 27 November 1906. pp. 8372–8373.

- Beard 2002, pp. 11–15.

- "No. 27825". The London Gazette. 8 August 1905. pp. 5477–5478.

- "No. 28300". The London Gazette. 22 October 1909. p. 7747.

- "No. 28634". The London Gazette. 9 August 1912. pp. 5915–5916.

- "No. 32753". The London Gazette. 6 October 1922. p. 7072.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 220–221.

- Photograph of Lord Ashfield cutting the first sod – London Transport Museum photographic archive. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 222.

- "No. 32769". The London Gazette. 21 November 1922. pp. 8230–8233.

- "No. 32850". The London Gazette. 3 August 1923. p. 5322.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 205.

- "1926 tube map". A History of the London Tube Maps. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 204.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 259–262.

- "No. 33668". The London Gazette. 9 December 1930. pp. 7905–7907.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 266.

- Tube maps from 1933 Archived 19 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 1936 Archived 22 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine and 1939 Archived 19 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, showing the changing names of the line from "A History of the London Tube Maps". Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "Northern line facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- "Call for action on Northern Line". BBC News. 12 October 2005. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- Stebbings, Peter (11 September 2006). "Five more years of Northern line pain". This Is Local London. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

Bibliography

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- Beard, Tony (2002). By Tube Beyond Edgware. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-246-1.

- Connor, J.E. (1999). London's Disused Underground Stations. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-250-X.

- Rose, Douglas (1999). The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.