Harlequin-type ichthyosis

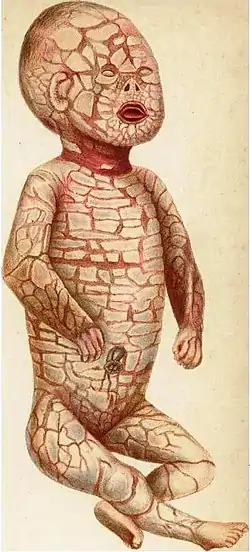

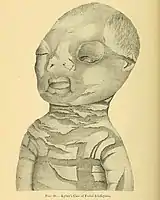

Harlequin-type ichthyosis is a genetic disorder that results in thickened skin over nearly the entire body at birth.[4] The skin forms large, diamond/trapezoid/rectangle-shaped plates that are separated by deep cracks.[4] These affect the shape of the eyelids, nose, mouth, and ears and limit movement of the arms and legs.[4] Restricted movement of the chest can lead to breathing difficulties.[4] These plates fall off over several weeks.[3] Other complications can include premature birth, infection, problems with body temperature, and dehydration.[4][5] The condition is the most severe form of ichthyosis, a group of genetic disorders characterised by scaly skin.[8]

| Harlequin-type ichthyosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Harlequin ichthyosis,[1] ichthyosis fetalis, keratosis diffusa fetalis, harlequin fetus,[2]: 562 ichthyosis congenita gravior[1] |

| |

| Harlequin-type ichthyosis, 1886 | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Very thick skin which cracks, abnormal facial features[3][4] |

| Complications | Breathing problems, infection, problems with body temperature, dehydration[4] |

| Usual onset | Present from birth[3] |

| Causes | Genetic (autosomal recessive)[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on appearance and genetic testing[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Ichthyosis congenita, Lamellar ichthyosis[3] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, moisturizing cream[3] |

| Medication | Antibiotics, etretinate, retinoids[3] |

| Prognosis | Death in the first month is relatively common[6] |

| Frequency | 1 in 300,000[7] |

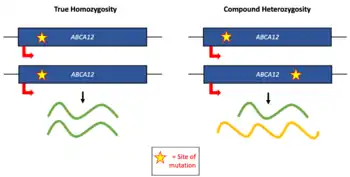

Harlequin-type ichthyosis is caused by mutations in the ABCA12 gene.[4] This gene codes for a protein necessary for transporting lipids out of cells in the outermost layer of skin.[4] The disorder is autosomal recessive and inherited from parents who are carriers.[4] Diagnosis is often based on appearance at birth and confirmed by genetic testing.[5] Before birth, amniocentesis or ultrasound may support the diagnosis.[5]

There is no cure for the condition.[8] Early in life, constant supportive care is typically required.[3] Treatments may include moisturizing cream, antibiotics, etretinate or retinoids.[3][5] Around half of those affected die within the first few months;[7] however, retinoid treatment can increase chances of survival.[9][8] Children who survive the first year of life often have long-term problems such as red skin, joint contractures and delayed growth.[5] The condition affects around 1 in 300,000 births.[7] It was first documented in a diary entry by Reverend Oliver Hart in America in 1750.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Newborns with harlequin-type ichthyosis present with thick, fissured armor-plate hyperkeratosis.[10] Sufferers feature severe cranial and facial deformities. The ears may be very poorly developed or absent entirely, as may the nose. The eyelids may be everted (ectropion), which leaves the eyes and the area around them very susceptible to infection.[11] Babies with this condition often bleed during birth. The lips are pulled back by the dry skin (eclabium).[12]

Joints are sometimes lacking in movement, and may be below the normal size. Hypoplasia is sometimes found in the fingers. Polydactyly has been found on occasion. The fish mouth appearance, mouth breathing, and xerostomia place affected individuals at extremely high risk for developing rampant dental decay.[13]

Patients with this condition are extremely sensitive to changes in temperature due to their hard, cracked skin, which prevents normal heat loss. The skin also restricts respiration, which impedes the chest wall from expanding and drawing in enough air. This can lead to hypoventilation and respiratory failure. Patients are often dehydrated, as their plated skin is not well suited to retaining water.[12]

Cause

Harlequin-type ichthyosis is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the ABCA12 gene. This gene is important in the regulation of protein synthesis for the development of the skin layer. Mutations in the gene cause impaired transport of lipids in the skin layer and may also lead to shrunken versions of the proteins responsible for skin development. Less severe mutations result in a collodion membrane and congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma-like presentation.[14][15]

ABCA12 is an ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC transporter), which are members of a large family of proteins that hydrolyze ATP to transport cargo across cell membranes. ABCA12 is thought to be a lipid transporter in keratinocytes necessary for lipid transport into lamellar granules during the formation of the lipid barrier in the skin.[16]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of harlequin-type ichthyosis relies on both physical examination and laboratory tests. Physical assessment at birth is vital for the initial diagnosis of harlequin ichthyosis. Physical examination reveals characteristic symptoms of the condition especially the abnormalities in the skin surface of newborns. Abnormal findings in physical assessments usually result in employing other diagnostic tests to ascertain the diagnosis.

Genetic testing is the most specific diagnostic test for harlequin ichthyosis. This test reveals a loss of function mutation on the ABCA12 gene. Biopsy of skin may be done to assess the histologic characteristics of the cells. Histological findings usually reveal hyperkeratotic skin cells, which leads to a thick, white and hard skin layer.

Treatment

Constant care is required to moisturize and protect the skin. The hard outer layer eventually peels off, leaving the vulnerable inner layers of the dermis exposed. Early complications result from infection due to fissuring of the hyperkeratotic plates and respiratory distress due to physical restriction of chest wall expansion.[17]

Management includes supportive care and treatment of hyperkeratosis and skin barrier dysfunction. A humidified incubator is generally used. Intubation is often required until nares are present. Nutritional support with tube feeds is essential until eclabium resolves and infants can begin nursing. Ophthalmology consultation is useful for the early management of ectropion, which is initially pronounced and resolves as scales are shed. Liberal application of petroleum jelly is needed multiple times a day. In addition, careful debridement of constrictive bands of hyperkeratosis should be performed to avoid digital ischemia.[17]

Cases of digital autoamputation or necrosis have been reported due to cutaneous constriction bands. Relaxation incisions have been used to prevent this morbid complication.[17]

Prognosis

In the past, the disorder was nearly always fatal, whether due to dehydration, infection (sepsis), restricted breathing due to the plating, or other related causes. The most common cause of death was systemic infection, and sufferers rarely survived for more than a few days. Improved neonatal intensive care and early treatment with oral retinoids, such as the drug isotretinoin, may improve survival.[12][9] Early oral retinoid therapy has been shown to soften scales and encourage desquamation.[18] After as little as two weeks of daily oral isotretinoin, fissures in the skin can heal, and plate-like scales can nearly resolve. Improvement in the eclabium and ectropion can also be seen in a matter of weeks.

Children who survive the neonatal period usually evolve to a less severe phenotype, resembling a severe congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. Patients continue to suffer from temperature dysregulation and may have heat and cold intolerance. Patients can have generalized poor hair growth, scarring alopecia, contractures of digits, arthralgias, failure to thrive, hypothyroidism, and short stature. Some patients develop a rheumatoid factor-positive polyarthritis.[19] Survivors can also develop fish-like scales and retention of a waxy, yellowish material in seborrheic areas, with ear adhered to the scalp.

The oldest known survivor is Nusrit "Nelly" Shaheen, who was born in 1984 and is in relatively good health as of June 2021.[20][21] Most infants do not live past a week. Those who do survive can live from anywhere around 10 months to 25 years thanks to advanced medicine.[22]

A study published in 2011 in the Archives of Dermatology concluded: "Harlequin ichthyosis should be regarded as a severe chronic disease that is not invariably fatal. With improved neonatal care and probably the early introduction of oral retinoids, the number of survivors is increasing."[23]

Epidemiology

The condition occurs in roughly 1 in 300,000 people. As an autosomal recessive condition, rates are higher among certain ethnic populations with a higher likelihood of consanguinity.[7]

History

The disease has been known since 1750, and was first described in the diary of Rev. Oliver Hart from Charleston, South Carolina:

"On Thursday, April the 5th, 1750, I went to see a most deplorable object of a child, born the night before of one Mary Evans in 'Chas'town. It was surprising to all who beheld it, and I scarcely know how to describe it. The skin was dry and hard and seemed to be cracked in many places, somewhat resembling the scales of a fish. The mouth was large and round and open. It had no external nose, but two holes where the nose should have been. The eyes appeared to be lumps of coagulated blood, turned out, about the bigness of a plum, ghastly to behold. It had no external ears, but holes where the ears should be. The hands and feet appeared to be swollen, were cramped up and felt quite hard. The back part of the head was much open. It made a strange kind of noise, very low, which I cannot describe. It lived about forty-eight hours and was alive when I saw it."[24]

The harlequin-type designation comes from the diamond shape of the scales at birth (resembling the costume of Arlecchino).

Gallery

_(14784247353).jpg.webp) Female case, 1888

Female case, 1888_(14784556735).jpg.webp) Male case, 1902

Male case, 1902 Kyber's case, 1902

Kyber's case, 1902 An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis.

An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis. An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis.

An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis. Harlequin ichthyosis in a female infant

Harlequin ichthyosis in a female infant Harlequin ichthyosis in a male infant

Harlequin ichthyosis in a male infant An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis covered in sterile gauze.

An infant with Harlequin ichthyosis covered in sterile gauze..png.webp) Harlequin ichthyosis in a 3-year-old girl, the keratin scales having almost completely fallen off

Harlequin ichthyosis in a 3-year-old girl, the keratin scales having almost completely fallen off

Notable cases

- Devan Mahadeo (June 11, 1985 – January 23, 2023) was born in Trinidad and Tobago, and lived to be 37 years old. He was involved in the Special Olympics for over 17 years and participated in both the Winter and Summer Games. He earned silver medals in football at Dublin, Ireland, in 2003 and Shanghai, China, in 2007, bronze in floor hockey at the 2013 Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, and gold at the 2015 Special Olympics World Games in Los Angeles, California.[25]

- Andrea Aberle (1969 – 2021) was 51 years old, making her one of the longest surviving individuals with harlequin ichthyosis, both in the US and globally. She lived in California with her husband before she died from skin-related complications.[26]

- Nusrit "Nelly" Shaheen (born in 1984) resides in Coventry, England, and was one of nine children in a Pakistani Muslim household. Four of her eight siblings also had the condition but died as young children. As of March 2023, Shaheen was among the oldest individuals with harlequin-type ichthyosis.[20][27]

- Ryan Gonzalez (born in 1986)[28] Currently the second oldest person with the condition living in the USA. He was featured in an episode of Medical Incredible.

- Stephanie Turner (1993[29] – 2017[30]) third oldest in the US with the same condition, and the first ever to give birth. Turner's two children do not have the disease. She died on March 3, 2017, at age 23.[31]

- Mason van Dyk (born 2013), despite being given a life expectancy of one to five days, was five years old as of July 2018.[32] Doctors told his mother Lisa van Dyke that he was the first case of harlequin ichthyosis in South Africa, and that she has a one-in-four chance to have another child with the disease.[33]

- Hunter Steinitz (born October 17, 1994) is one of only twelve Americans living with the disease and is profiled on the National Geographic "Extraordinary Humans: Skin" special.[34]

- Mui Thomas (born in 1992 in Hong Kong) qualified as the first rugby referee with harlequin ichthyosis.[35]

- A female baby born in Nagpur, India, in June 2016 died after two days. She was the first case reported in India.[36][37][38]

- Hannah Betts: Born 1989 in Great Britain; died in 2022 at 32 years old.[39]

- Ng Poh Peng was born in 1991 in Singapore. Doctors had not expected her to live past her teenage years. In 2017, she was 26 years old.[40]

References

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- "Ichthyosis, Harlequin Type – NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2006. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- "Harlequin ichthyosis". Genetics Home Reference. November 2008. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- Glick, JB; Craiglow, BG; Choate, KA; Kato, H; Fleming, RE; Siegfried, E; Glick, SA (January 2017). "Improved Management of Harlequin Ichthyosis With Advances in Neonatal Intensive Care". Pediatrics. 139 (1): e20161003. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1003. PMID 27999114.

- Schachner, Lawrence A.; Hansen, Ronald C. (2011). Pediatric Dermatology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 598. ISBN 978-0723436652. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017.

- Ahmed, H; O'Toole, E (2014). "Recent advances in the genetics and management of Harlequin Ichthyosis". Pediatric Dermatology. 31 (5): 539–46. doi:10.1111/pde.12383. PMID 24920541. S2CID 34529376.

- Shibata, A; Akiyama, M (August 2015). "Epidemiology, medical genetics, diagnosis and treatment of harlequin ichthyosis in Japan". Pediatrics International. 57 (4): 516–22. doi:10.1111/ped.12638. PMID 25857373. S2CID 21632558.

- Layton, Lt. Jason (May 2005). "A Review of Harlequin Ichthyosis". Neonatal Network. 24 (3): 17–23. doi:10.1891/0730-0832.24.3.17. ISSN 0730-0832. PMID 15960008. S2CID 38934644.

- Harris, AG; Choy, C; Pigors, M; Kelsell, DP; Murrell, DF (2016). "Cover image: Unpeeling the layers of harlequin ichthyosis". Br J Dermatol. 174 (5): 1160–1. doi:10.1111/bjd.14469. PMID 27206363.

- Kun-darbois, JD; Molin, A; Jeanne-pasquier, C; Pare, A; Benateau, H; Veyssiere, A (2016). "Facial features in Harlequin ichthyosis: Clinical finding about 4 cases". Rev Stomatol Chir Macillofac Chir Orale. 117 (1): 51–3. doi:10.1016/j.revsto.2015.11.007. PMID 26740202.

- Rajpopat, S; Moss, C; Mellerio, J; et al. (2011). "Harlequin ichthyosis: a review of clinical and molecular findings in 45 cases". Arch Dermatol. 147 (6): 681–6. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.9. PMID 21339420.

- Vergotine, RJ; De lobos, MR; Montero-fayad, M (2013). "Harlequin ichthyosis: a case report". Pediatr Dent. 35 (7): 497–9. PMID 24553270.

- Akiyama, M (2010). "ABCA12 mutations and autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis: a review of genotype/phenotype correlations and of pathogenetic concepts". Hum Mutat. 31 (10): 1090–6. doi:10.1002/humu.21326. PMID 20672373. S2CID 30083095.

- Kelsell, DP; Norgett, EE; Unsworth, H; et al. (2005). "Mutations in ABCA12 underlie the severe congenital skin disease harlequin ichthyosis". Am J Hum Genet. 76 (5): 794–803. doi:10.1086/429844. PMC 1199369. PMID 15756637.

- Mitsutake, S; Suzuki, C; Akiyama, M; et al. (2010). "ABCA12 dysfunction causes a disorder in glucosylceramide accumulation during keratinocyte differentiation". J Dermatol Sci. 60 (2): 128–9. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.08.012. PMID 20869849.

- Tanahashi, K; Sugiura, K; Sato, T; Akiyama, M (2016). "Noteworthy clinical findings of harlequin ichthyosis: digital autoamputation caused by cutaneous constriction bands in a case with novel ABCA12 mutations". Br J Dermatol. 174 (3): 689–91. doi:10.1111/bjd.14228. PMID 26473995. S2CID 34511814.

- Chang, LM; Reyes, M (2014). "A case of harlequin ichthyosis treated with isotretinoin". Dermatol Online J. 20 (2): 2. doi:10.5070/D3202021540. PMID 24612573.

- Chan, YC; Tay, YK; Tan, LK; Happle, R; Giam, YC (2003). "Harlequin ichthyosis in association with hypothyroidism and rheumatoid arthritis". Pediatr Dermatol. 20 (5): 421–6. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20511.x. PMID 14521561. S2CID 19314083.

- Lillington, Catherine (April 14, 2016). "Inspirational Nusrit Shaheen is still smiling despite battling condition which makes her skin grow ten times faster than normal". Coventry Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- THE SNAKE SKIN WOMAN: EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE, Channel 5, March 22, 2017.

- Shruthi, Belide; Nilgar, B.R.; Dalal, Anita; Limbani, Nehaben (June 1, 2017). "Harlequin ichthyosis: A rare case" (PDF). Journal of Turkish Society of Obstetric and Gynecology. 14 (2): 138–140. doi:10.4274/tjod.63004.

- Rajpopat, Shefali; Moss, Celia; Mellerio, Jemima; Vahlquist, Anders; Gånemo, Agneta; Hellstrom-Pigg, Maritta; Ilchyshyn, Andrew; Burrows, Nigel; Lestringant, Giles; Taylor, Aileen; Kennedy, Cameron; Paige, David; Harper, John; Glover, Mary; Fleckman, Philip; Everman, David; Fouani, Mohamad; Kayserili, Hulya; Purvis, Diana; Hobson, Emma; Chu, Carol; Mein, Charles; Kelsell, David; O'Toole, Edel (2011). "Harlequin Ichthyosis". Archives of Dermatology. 147 (6): 681–6. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.9. PMID 21339420.

- Waring, J. I. (1932). "Early mention of a harlequin fetus in America". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 43 (2): 442. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1932.01950020174019.

- "Special Olympics Trinidad and Tobago mourns top ex-athlete - Trinidad and Tobago Newsday". Newsday. January 23, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- "First Skin Foundation, "Andrea A.* - Moreno Valley, CA - 2020". First Skin Foundation. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- "Harlequin Ichthyosis". Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- "Man Survives Rare Skin-Shedding Disease - Staying Healthy News Story - KGTV San Diego". 10news. November 16, 2004. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- Madden, Ursula (August 26, 2013). "Mid-South woman with rare genetic condition defies odds, deliverers healthy baby". Fox19 Cincinnati. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- "Mid-South woman born with rare skin condition dies unexpectedly". WMCActionNews5. March 7, 2017. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- "[UPDATED] I'm the First Woman with Harlequin Ichthyosis to Give Birth". January 5, 2017. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Wilke, Marelize (July 6, 2018). "This strange disorder gives children very hard, thick skin". News24. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "21-month-old boy defies the odds, thrives living with Harlequin Ichthyosis". News24. December 31, 2014. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- Hamill, Sean D. (June 27, 2010). "City girl aims to educate about her skin disease". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on June 30, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- "'Girl behind the face' tackles cyber bullies". scmp.com. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016.

- "Nagpur: Harlequin baby dies two days after birth". hindustantimes.com. June 13, 2016. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- "India's first 'Harlequin Baby' born without any external skin dies two days after birth". India TV. June 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Shahab, Aiman (September 7, 2020). "Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis In Infant With Harlequin Ichthyosis". MEDizzy Journal. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- "Woman whose skin grew too fast for her body dies at 32". May 25, 2022.

- Asia One, "Woman born with rare skin disease: My parents love me, that's enough," April 28, 2017

External links

- Information from the U.S. National Institutes of Health